The ends of public schools and why society needs teachers1

Los fines de las escuelas públicas y por qué la sociedad necesita a los profesores

DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-395-526

Maria Mendel

Tomasz Szkudlarek

Uniwersytet Gdański

Abstract

In this paper we intend to imagine, by way of delimitation, and perhaps a detour of spaces that appear to be emptied from their significant presence, the role of teachers in society where recent developments challenge political and cultural foundations of education in its shape we had known as implicated in the construction of modern states in Europe; in society where one often hears of the end of public school. However, the notion of the end will be problematized here as well, and we will reflect not so much on the end, but on a complex occurrence of multiple ends of public schools. These reflections suggest a peculiar ontology of ending, of a time of exhaustion when things slip out of our hands and no aims can be seen clearly on the horizon. And, as according to what we have announced here, ends appear as multiple here, we shall suggest four overlapping ontologies of ending. Clinging to the ambiguous meaning of the word, we shall try to position the figure of the teacher within this ending ontology, drawing the ends of their work (now read as aims) from the ends of public school. Perhaps, in the world where we witness the end of nature, the end of security, the end of future if one might risk to put it succinctly (Szkudlarek, 2017), this is, ultimately, the only way of thinking of ends of teachers’ work.

Key words: public school, ends of education, teachers’ work.

Resumen

En este trabajo pretendemos imaginar, por medio de la delimitación, y tal vez un desvío de espacios que parecen vaciarse de su presencia significativa, el papel de los docentes en una sociedad donde los recientes desarrollos desafían los fundamentos políticos y culturales de la educación en su forma hasta ahora conocida, como implicados en la construcción de estados modernos en Europa; en una sociedad donde a menudo se oye hablar del fin de la escuela pública. Sin embargo, aquí también se problematizará la noción de finalidad, y reflexionaremos no tanto sobre la finalidad, sino sobre una compleja sucesión de múltiples fines de las escuelas públicas. Estas reflexiones sugieren una peculiar ontología de la finalidad, de un tiempo de agotamiento en el que las cosas se nos escapan de las manos y no se vislumbran claramente objetivos en el horizonte. Y, como de acuerdo con lo que hemos anunciado aquí, los fines aparecen como múltiples, aquí sugeriremos cuatro ontologías de orientación superpuestas. Aferrándonos al significado ambiguo de la palabra, intentaremos ubicar la figura del docente dentro de esta ontología de la finalidad, definiendo las finalidades de su actividad (ahora leídos como objetivos) desde los fines de la escuela pública. Quizás, en el mundo en el que somos testigos del fin de la naturaleza, el fin de la seguridad, el fin del futuro, si uno puede arriesgarse a decirlo de manera sucinta (Szkudlarek, 2017), esta es, en última instancia, la única forma de pensar en los fines de la tarea de los docentes.

Palabras clave: escuela pública, fines de la educación, tarea docente.

Introduction

In this paper we intend to imagine a role of public schools and teachers in society where political and cultural foundations of education, understood as implicated in the process of modernization, are shaken, and where we hear about the end of public school repeatedly. We see such these negative prophecies as linked to more general ontologies of ending, of a time when things wane, disintegrate, or slip out of control. Ending seems persistent and productive of conditions of risk, loss, insecurity and fear and, at the same time, of strategies of survival and inviting yet unknown futures. This ending condition has been announced for ages. Christianity has always been obsessed with the end of the world (and salvation of chosen ones). Astrophysicists supplemented that framework, minus salvation, with notions of entropy and thermal death of the universe. Grand metaphysical projects of modernity, like Hegel’s and Marx’s, construed logics that lead to the end and turned post mortem salvation into retroactive consciousness and emancipation. Then the postmodern condition defined itself as culture of exhaustion and termination of the progressive matrix, save the progress in technology: we stay where we are and all we can do is re-mix inherited signs and ideas for recreating our identities. End is here and now – to use Beckett’s words, all is “finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished” (Beckett, 2009). It was within the postmodern turn, seamlessly glued with neo-liberal economy of global capitalism (Callinicos, 1990) when we identified numerous ends major and minor: of modernity, of the subject, of democracy, of reason, of science, of theory, and of the school as well. Deschooling once proposed by Illich returned in fragments in neoliberal reforms that reduced education to learning and schooling to provision of individually measured outcomes. Against this backdrop the end of school appears as a long-lasting ontological condition within which we teach, learn, and try to make sense of education.

We want to amplify this ending condition here to see what interests might make people want to liquidate public schools or abandon them to their slow decay; to see what we are losing, why it hurts, and – via those detours – what are the values that make some eager to liquidate schools while others resist or mourn their death. If indeed value of the school can be seen via its ending ontologies, one could also assume that the present wave of exposing the value of the scholastic (e.g. Biesta, 2017; Masschelein and Simons, 2013) can also be read – like in Hegel’s metaphor of Minerva’s owl – as implicated in school’s ending as its condition of possibility.

We see the end of school as plural. There are various ways of schools being reduced, diminished, liquidated, or pushed to the margins. There are, therefore, diverse end of public-school ontologies – modes of being, shrinking or surviving, sometimes expanding into niches where such moves are possible in the state of ending. Vattimo’s hermeneutic understanding of ontology as interpretation of our condition in the process of becoming history (Vattimo, 1991) matches this approach very well. As long as one can distinguish between such ontologies endlessly, we speak of two major ones and of some modalities, or ontologies minor within them. First major ontology links to neoliberal management and privatization of the public. We illustrate it with cases of recent educational policies in Poland, but they are typical of societies where neoliberal reforms introduced strict measures of efficiency and financial control. We will describe three “ontologies minor” within this trait. The second major ontology relates to developments of new media that contribute to fragmentation of the public and its parcellation into insulated filter bubbles. What is questioned here is not the public logic of the school, but the institution of the school as such. However, the very same revolution is productive of crises of what is public and of rational underpinnings of public life in general, so it is not only public school, but public life and rationalism that demand attention here. And because we have an institution that was invented to create rational foundations for public life, which is public school, in the concluding part we close the circle. The lucky ambiguity of the term “ends” helps us to reverse the direction of our reflection and see what ends become visible through the varied ontologies of the school ending, and to reflect on ends of teachers’ work finally.

We do not promise to end this reflection with unexpected aims of teaching. The sense of our work here is, rather, to articulate educational concerns with the endgame of schooling. Living in the end tends to be driven by desires to delay, postpone, or push away the ultimate horizon of termination. Even though much of how we understand teaching is defined by introducing, beginning, or developing – after all, education has become a public issue in course of progress and modernization – under present conditions the ideas of conserving against decay or forgetfulness, preventing from destruction and surviving, always implicated in the idea of education as well, are understandable and they often dominate those related to “good old progress”. As Gert Biesta (2017) has noticed, conservative ideas (the rediscovery of teaching included) gain a radical edge nowadays and may work for the benefit of progressive values.

Genealogical reminder

The emergence of modern education systems in Europe followed the proliferation of print and the emergence of reading publics, Reformation with its numerous denominations, Counter-Reformation and religious wars, and the conviction that it is us humans (rather than fate, God, or historical necessity) who are responsible for the shape of the social, an idea aptly expressed by Immanuel Kant (Kant, online), may all be seen as effects of print. The French Revolution was a critical moment here: seen by Kant as realization of human freedom and moral autonomy, it was also a horrific experience that initiated the quest for emancipation otherwise than by violence. Public education was then postulated as alternative to revolution (Tröhler et al., 2011). Modern democracy and republicanism are, in this context, politically grounded in demands for knowledge being accessible to all and–to use Kant again–in encouraging individuals to using reason in public.

Of course, this genealogy is not the only one, nor is it binding for those who run schools nowadays. As we have learned from Foucault (Foucault, 1980), institutions set up for one particular reason change functions and modes of operation continuously; fundamental ones may disappear, while marginal ones may turn constitutive of new power regimes. Still, it is worth remembering that school is one of very few institutions at hand that could address democratic challenges, and that teachers can revitalize the public use of reason as counteracting both endemic ignorance (which was the challenge in the time of Kant) and what Stiegler (Stiegler, 2015) calls organized stupidity nowadays. Unless we replace the school with another public space for re-construing the social, we need to keep it alive and see it as even more political than it was at the time of its birth.

Transformations of the public in public education in Poland

As we are using examples from Poland to discuss the first ontology of public school’s ending, we need to start with a brief history of schooling in the country after World War Two, during the post-communist transition with its neoliberal policies, and after the nationalist PiS party won parliamentary elections in 2015.

Until 1989, the post-war Poland was a Soviet-style socialist state with certain liberal deviations. Public education was defined through the prism of modernization and social justice. However, despite of ideological assumptions, selection and class segregation were endemic to its education system. Massive vocational education, linked to rapid investments in heavy industry, was promoted as emancipation for rural youth, while small urban cohorts might enjoy elite licea. In the 1970s, researchers began to expose such inequalities as hidden curricula, and dramatic differences in educational opportunities between urban and rural youth were highlighted (Kwieciński 1972). After students’ rebellion in 1968 candidates with working class background were promoted in university enrollments, but it was interpreted as breaking solidarity of students in protest. The state legitimized itself as socialist, but workers’ strikes in 1970 ended with week-long massacres in the streets. In short, socialism and equity gained a meaning of oppression, and such values became easy to marginalize after the Solidarity upheaval of 1989. Economic development and personal liberty turned out to be more significant, and those demands affected schools and education policies deeply. Politically, such demands could be accomplished under condition of creating a strong middle class, which was overtly proclaimed by post-1989 governments.

Indeed, middle-class parents engaged actively in breaking state monopoly in education and demanded freedom, not equality (Mendel, 1998). Parental movements gained strength and led to diversification of a previously homogeneous, state-run education. Parents-run Szkoły Społeczne (“social”, as opposed to “state” schools) appeared in 1989 along with for-profit private schools and schools run by associations, foundations etc. In the 1990s such institutions hosted about about 2% of schoolchildren. Diversification tendencies gained impetus after Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004, when catching up with the West was accompanied by strong class polarization and distinctions built on educational criteria. Parents-run schools and home-schooling associations began to run away from public control and open recruitment, while continually drawing on public resources. This wave of class-based diversification, strengthened by regulations on school choice and external examinations with publicly available results, resulted in deep segregation in urban public schools as well (Dolata, 2008).

Since the 2000s one could see efforts to reconcile neoliberal management and the concern with common good, as represented by open, public schools. The end of public school, although proclaimed, has not come (Mendel, 2018), or, so to say, it has not “ended” in a concluding closure: it lingers on, proliferates into diverse modalities, and schools slowly erode in some dimensions and develop in others. The overwhelming majority of schools remained public. Run by local governments, they keep enjoying respect and many offer innovative, quality education. However, the situation of local governments has become very difficult after the 2015 elections. In 2016, the nationalistic government introduced a massive structural reform (labeled “deform” by teachers’ unions) and charged local governments with its immense costs. This move, together with reductions in tax revenues, brought financial problems to local communities. Moreover, the national government keeps changing core curricula and an immense pressure on religious and national values is threatening to minority and liberal-minded students and brings a suffocating atmosphere to everyday schooling.

In view of these changes, the question arises about the “public” in public education in Poland. An interesting criterion of what public means was proposed in 1945 in the USA, when the court of State of Connecticut decided that such schools must be under the exclusive control of the state, and that they must be free from sectarian instruction (Miron and Nelson, 2002). The fact that Polish schools, as a result of the last reform, work on the basis of detailed national curriculum seems to over-fulfill the first condition. However, the intensifying pressure of ministers of education towards nationalism and Catholic fundamentalism means that the state does not provide freedom from sectarian instruction.

This landscape gains more complexity when we ask who owns or controls schools. Privatization tendencies are still present in Poland, and those are diverse enough to be discussed as specific “ontologies minor” within the general ontology of privatization.

The ends of public school: privatization

Announcing the end of school is a frequent reaction to privatization, to class- or race-based segregation, etc. (Giroux, 2015; Hursh, 2015; Mendel, 2018; Uryga, 2017), but we see this development as complex and sometimes intentionally disrupted or hybridized. Andre E. Mazawi interprets such processes as related to shifts in the construction of contemporary states that become “network states” with “graduated sovereignty”, combining public and non-public actors around particular functions and operations. In this perspective, education is part of transformations of the very nature of the public (Mazawi, 2013) and privatization is not always synonymical with abandoning public functions. “The end of public school” in Poland can be interpreted as implicated in such changes. Within this general ontological condition, we see three modes, or micro-ontologies in which it can be observed in Poland.

First involves actions for profit where means are dragged from public to non-public sphere. This “direct privatization” ontology can be compared to charterization in the USA. Even though the rhetoric of public good is in service of privatization agendas, the key issue remains that schools turn into profitable businesses that take public money but escape public control, and that they become property of its operators. In Poland such transitions are usually gradual (“creeping” privatization, Sześciłło, 2013). It happens when local communities transfer schools to non-public operators without agreements that would secure buildings and ground from overtaking (Dziemianowicz-Bąk and Dzierzgowski, 2014). Such lots are often spacious and always well communicated with other establishments, which makes them attractive for private owners. In the USA, premises of schools liquidated because of poor pedagogical performance are frequently turned into investment grounds and sold to developers. Pauline Lippman (2011) says that the very process of performance control is part of urban policies of revitalization. Even in creeping privatization that we see in Poland, transfers to private operators are indeed opening possibilities for small groups of individuals to take over real estate (Dziemanowicz-Bąk and Dzierzgowski, 2014).

The second is a “soft privatization” ontology. It concerns small schools in rural environment that–under New Public Management rules–prove too expensive for local communities to run. Massive resistance against their closures made the then liberal government pass a so-called Small Schools Act that allowed for transferring them to local NGOs as operators. Some of such schools, or rather their buildings and lots, have eventually become properties of few-person associations that had saved them from liquidation once. However, researchers led by Krystyna Marzec-Holka (2015) who examined all small schools in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian region stated that in general such local associations play an active, animating role in their communities and contribute to development of local democracy. Hard-line neoliberalism is being softened here: schools are rescued from liquidation in spite of being economically ineffective and increase their public impact. However, it may still lead to real estate privatization, for instance when children of the founders grow up, teachers retire, and there is no will to continue the work of the association.

Apart from direct privatization and its soft or delayed form, there is a third one that we call hybrid ontology. An example can be a new school built by the city of Gdańsk, described by city officials as “a free, public school with a broader offer, innovative management and doors wide open to the local community” (Majewska, 2017). Built and equipped with public money, the school was immediately transferred to a private foundation for operation, while the city remained its owner to guarantee open enrolment policy and control the curriculum. The school offers its modern facilities to the neighbourhood and is becoming an important place for the development of local civic activity. The Gdańsk project subscribes into a “managerial privatization” (Mazawi, 2013) path in education. Contrary to the ontology of direct privatization, public good dominates other profits here: the school has not become private property and the city controls its operation. The assessment of this path is still not unambiguous, but the hybrid created in Gdańsk may illustrate how “graded sovereignty” (Mazawi, 2013) works and how the neo-liberal paradigm can be used by people oriented to democratic commonality. Still, there is a shadow in this luminous case: teachers are not being employed according to union’s regulations. In this respect, there is no difference between this hybrid case and other forms of privatization.

In 2015 and 2019, populist – nationalist PiS party won parliamentary elections under a socially oriented agenda and the promise to strengthen the role of the state. Paradoxically, effects of their social and educational policy reinforce privatization tendencies. Introduction of generous child benefits for all families, with a simultaneous deterioration of financial situation of local governments who run public schools, result in rapid growth of private schooling. The party that loudly pronounces taking side of ordinary people is thus increasing class inequalities in education, replacing the policy of social cohesion with that of national identity – the public returns here in a mythical, nationalistic articulation.

End of school ontologies and losing teachers

In diverse ways and degrees, privatized schools still perform public functions. However, the factor that unites them is that teachers are victims of their transformation. Privatization, hard, soft or hybrid, concerned or unconcerned with public good, allows operators to employ teachers with disregard of Teacher’s Charter that has regulated the profession since the socialist times. In the managerial discourse those regulations are denigrated as obstacle to schools’ efficiency, and public opinion is being attacked with revelations of teachers working short hours and enjoying extensive paid holidays. The aura of forcing teachers to work more results–in schools that escape public regulations–in bigger workloads, unpaid holidays, lack of resources for in-service training, the lack of permanent contracts and other deviations from union agreements, sometimes compensated by somewhat higher salaries: “There are teachers who work from 3rd September to 28th June (…) In the summer they are unemployed and have to register in a Job Agency. (…) There are cases when the teacher is fully employed but apart from giving classes, they have to rake leaves in the school’s area as well” – says the president of the teachers’ unions” (Zakrzewski, 2014). Even though non-public school operators often respect many of union regulations, teachers in these schools always work under less favourable conditions. The Teacher’s Charter was created in 1982 to buy teachers’ consent to the regime that decided to crash the Solidarity movement. The debate on its sense today exposes that fact to delegitimize its very idea, but it misses its essential meaning of a collective work agreement, which is nothing exceptional in professional environments. Nowadays this attack adds to an open fight against “old elites” that includes public depreciation of judges, artists, teachers, medical doctors or academics – a populist discourse that allows PiS to make room for their substitutes nominated by the party.

“Losing teachers” also means that the system loses qualified professionals. Teachers quit jobs massively, especially after the recent nomination of a fundamentalist Catholic for minister of education and the announcement that the state budget, in deficit caused by generous benefits and lack of transparency in public spending, will not allow for rising salaries in public sector. In September 2021 ca. 15 000 teachers were missing in Poland. However, teachers may quit jobs for other reasons as well. Tony F. Carusi, in his analysis of education policies in the USA, points to a paradoxical situation where massive loss of teachers results from them being recognized as key factor in their students’ performance. Being decisive in the “Race to the Top” (the current US education agenda) does not bring job satisfaction: in a system driven by constant measurement it exacerbates the burden of responsibility and makes teachers first to blame for anybody’s not reaching the top. When asked by their students for advice as to further education, teachers strongly discourage them from becoming teachers (Carusi, 2017).

The end of public school and the end of print

As we have mentioned, modern school emerged in culture of print. Even though paper mills and printers still work hard, the print has lost its status of defining technology, and that change was spotted already with the advent of television (McLuhan, 1994). Web 2.0 and social media are late steps on the ladder that grounds in that McLuhanian revolution, but the turn to social media, which comes together with the incredibly fast development of artificial intelligence algorithms, seems to be of unprecedented importance.

Social media do not negate but transform the public. Powered by advanced AI engines, they elevate a particular form of the public to unprecedented heights. In a way, they mimic traditional neighborhoods in how they “swallow” the private and mold shared opinion about other private beings and “remote public” issues. AI algorithms supply individuals with information tailored to private needs and preferences, extending that commercial logic onto the whole domain of information and learning. Not only is this a matter of information being available without the mediation of textbooks or teachers; it is also about thinking, deliberating, and acting publicly which apparently does not need to be taught at school. It is easy to claim that schooling, with its linear-sequential logic copied from the matrix of print, is at odds with new media, with how we use touchscreens or read hypertext. Stefano Oliverio (Oliverio, 2020) speaks in this context of a “techno-revolutionary tone” in education. Public school ends here not only through transformations of the public, but through an alleged redundancy of the school itself. But what kind of public we become when mediated by touchscreens, bots, and social media?

Knowledge, politics, and the media

As we keep repeating, modern democracy and republicanism have been genetically grounded in demands for knowledge being accessible publicly. As long as Wikipedia reinvigorated hopes for a globally informed public sharing rationally moderated knowledge, the era of Facebook means disintegration of what was hoped to become the new Commons – public sphere where “all knowledge” was meant to be provided “for all” and co-produced by everybody (these are the founding ideas of the Wikipedia). Social media close us in filter bubbles, isolate us from differences, industrialize political marketing, intensify political manipulation, and thus contribute to the crisis of democratic culture (Bendall and Robertson, 2018). Theodora Diana Chiş quotes Nicolas Negroponte who in 1995 provoked readers with his futuristic vision: “Imagine a future in which your interface agent can read every newswire and newspaper and catch every TV and radio broadcast on the planet, and then construct a personalized summary. This kind of newspaper is printed in an edition of one” (Chiş, 2016, p. 5). We have arrived at this future, and we have a social life here – we share such news composed “for one” within enclosed communities of our choice.

Social media are by and large driven by emotions: what literally counts within our bubbles is liking and being liked, and what it provokes in reaction to other bubbles easily is hate. This identity mechanism constitutes a perfect machinery for contemporary politics, often described in Carl Schmitt’s terms as driven by the construction of enemy (Schmitt, 2008). Political marketing and populist manipulation have never been so easy before. A most widely known case is Cambridge Analytica forging US election campaigns by using Facebook data of millions of voters (Nix, 2016). In the background there is a sophisticated “psychographic algorithm” that correlates digital traces people leave online and a five-dimensional personality model. It allows for testing our personality online without us knowing that we are being tested. As the authors of the algorithm claim, such Internet-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans (Youyou et al., 2015). Arguments for voting Trump could be fine-tuned to personality profiles of any Facabook user in the USA. If democratic public schools were meant to educate citizens who cast their votes upon individual rational judgment, this task has become far more difficult than it was ever before.

Ends of school: How its ending suggests its aims

What ends for educational re-action (reacting to those ending modalities, as well as acting again for public good) can we see in the end of school ontologies? Drawing ends for action from ends that terminate action demands a move of retrojection and negation in one, of projecting catastrophic images of end backwards, onto the beginnings and trajectories of coming to an end. It is a paraphrase of Hegelian dialectic, where negativity is inherent in every being and termination is at the same time its fulfillment and beginning of a new process in which negativity is sublated by a new “positive” identity capable of hosting old and creating new negativity. So what ends of public schooling shine through their endgames today?

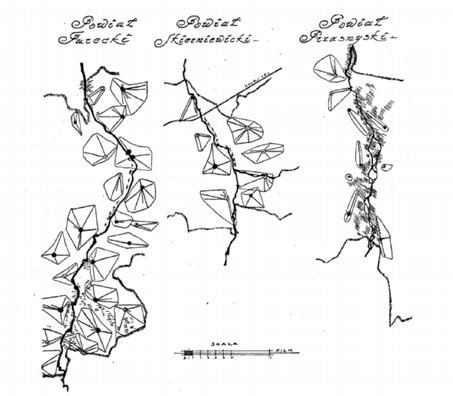

In the privatization (direct, soft or hybrid) ontology we can see that schools are problems or objects of desire as purely material beings: as buildings and lots of precious land that is “wasted” when used for children’s games and obsolete instruction as buildings uselessly packed with books that no one reads and computers that lag behind those that children have at home. The value of schools lies with their brick-and-mortar fabrics, and most of all with the place they occupy (sic!) in the neighborhood. In the time of public school system being constructed, the location of schools demanded sophisticated logistics. Schools had to be set in a child’s walking distance within or between local housing establishments, in places, sizes and numbers that had to take the size of given communities into account, in places where there was enough space to provide room for children’s physical activity, etc. (Falski, 1925). Andre Mazawi (2013) speaks of their territorializing function. Schools delimit borders and bind communities to given localities, they become hubs between smaller communities or centers within larger ones. They may be relics of open space in densely built urban areas or cozy shelters in the open, between scattered farmhouses. In short, they sit in perfect places for people to associate. In course of time, built settlements tightened around them, and nowadays schools often remain largest enclaves of perfectly communicated space in densely built areas. This is why they become objects of predatory housing policies. Dream locations for shopping centers.

Schools are also valuable because of money invested; in Marxist terms, because of work invested in their classrooms, gyms and dining rooms; or in teachers’ qualifications that took time and public resources to acquire. This is residual value which can be read as negative burden, money wasted for something that does not work and cost for those who manage public finances, or as expectation, a promise of return for those who put effort into their establishment or whose children can just walk to school. This conflicting nature of monetary value is productive of strategies bridging those who want to get rid of costs with those desperately wanting the school to operate – like teachers and parents in rural communities who take over the school to run it themselves. In other cases (cf. Gdańsk hybrid), agreement between parties involved allows for schools keeping open recruitment, high standards of performance and operating as community centers, and being affordable to the shrinking finances of local governments – at the cost of teachers’ working conditions.

We also see that school is an object of competition between conflicting authorities. In case of Poland, the PiS policy aims at centralization of nearly anything. Local governments, and those of large cities in particular are their annoying obstacles. Making running schools hard for local governments by charging them with costs of massive restructuration and limiting their tax revenues, means that the state will be able to “rescue” public schools (they have already practiced it with some theaters or museums) and then change their managerial staff and programs of their activities. Schools, as social hubs, and places where knowledge and attitudes are created, are critical places where the nature of social bonds and identities is being defined. In a centralized state driven by nationalist sentiments, its function is to unify mind-frames of the population by pride, myths, and fear rather than by civic competence, and thus to secure the ruling clique against being overthrown in elections. The second value that shines through this ending ontology is, therefore, that of shared knowing.

And there is one more value visible in the struggle for public schools in Poland nowadays. In conversations with parents, we hear that some seek private schools not because they need to satisfy their middle-class ambitions, but because they want to save their children from religious indoctrination. Catholic religion is taught in public schools, usually by priests, and children who do not attend the classes need to spend time in common rooms, thus forced to demonstrate their difference in public. The present minister for education decided to make religion or ethics classes obligatory, and in shortage of ethics teachers their training was commissioned in Catholic universities. Referring to the Connecticut criteria, public schools cannot protect their children from sectarian teaching when the state is sectarian itself. In this variety of the end of public school, private schools are perceived as safe havens for minorities, and it is those schools who perform this crucial function of public schooling.

Turing to the second ontology of the end of school, one related to new media, we can suspect a set of neoliberal desires operational here as well (reducing costs by digitally assisted home schooling, etc.) But we may also spot expectation that schools, in their present or modified form, could help make sense of digital culture, help invent its grammars – a thing that they did to print. What is at stake is not only different skills needed in digital environments, but first of all, the density of the horizontal, rhizomatic structure of this environment and its parcellation into self-sustainable bubbles insulated from other nodes of the web. This environment lacks grammar and vocabulary that would enable communication across the bubbles, and even though there are travelers and interpreters, there are no common spaces (like market squares in ancient cities) where they could be met easily. What we are heading at now is the figure of a teacher that could work as traveler and storyteller who initiates the construction of transversal reason – a notion Wolfgang Welsh (1995) proposed as response to the postmodern crisis of universality. This concept is found adequate to the research on World Wide Web (Sandbothe, n.d.), and we believe it is valuable for education in the digital world. For the time being, this ontology is a perfect hunting ground for commercial and political marketeers who find their prey perfectly sorted, legibly tagged, and grouped in comfortably homogeneous enclaves. Can those be turned into communities – and can those form a kind of society where their worldviews interact and where they learn to develop a notion of common good? Some hope of this kind was visible, for instance, during the protests against ACTA regulations that were interpreted as imposing policing control over the Web in Europe (Lee, 2012). However, nobody is interested in maintaining such commonness when threat (or occasional fascination) disappears.

Closing the circle: Reclaiming teachers and public schools

Throughout this argument we claim that privatization and new media undercut both public school as institution, and public sphere that is the space for republican political orders and democratic practices. At the same time, public school was one of crucial institutions that created those disappearing public spheres and citizens who could make democratic use of them. Reclaiming public schools seems to be, therefore, a point of dissection where this circle of demolition could turned into thinking of new futures for democracy.

It seems that to imagine ends of public schooling and teacher’s work that correspond to the ontological condition of their ending requires that we take physical and virtual spaces into account simultaneously; that we treat such issues as privatization of schools, segregation of urban spaces, dissection of World Wide Web into insulated bubbles, populist politics that use AI to corrupt elections campaigns, and education reduced to serving human capital to global capitalism or producing voters to populist reactions against global capitalism, as elements of the same puzzle. After all, all those developments and both ontologies we discuss here are product of capitalist logic of parcellation, privatization and profit. This logic operates in the ontology of end of public school and discloses values that reveal its ends.

Let us start with physical space. In the 1980s Henry Giroux (2015) observed that public school is the last public sphere, i.e., one that is free from segregation at the entry gates. This observation only gains importance nowadays when schools become more and more segregated. If we wonder where we make young people isolated by physical and virtual arrangements meet and talk over their concerns, public school is (still) there. School is the place where they may learn where are the limits of what is familiar, about difference, otherness and the unheimlich that do not allow to “rest in peace” within the familiar. This is a value of teaching that cannot be attained by learning alone (Biesta 2017).

What we are learning from school’s ending via privatization and segregation is that schools are fundamentally important locations in physical space: places for doing things together, binding hubs where individuals enter public scene to share and confront their thinking and experience limits to what has been familiar to them. Also, despite the unprecedented availability of online content, places where common knowledge can be pursued through purposefully invented practices. They remain connected to the external world, but are capable of inventing and maintaining knowledges that have no practical connection to that world and can therefore socialize to possible rather than actual realities. They are also intimate places, frequently in a walking distance for anyone within the community, and accessible to those from other communities as well. They are invested with local histories, memories, and future expectations, and can therefore support communities, individuals and societies in their becoming. They can bind or separate generations, classes, genders and races, religious denominations, and political ideologies. Their work is, at the same time, about gradual grammatization of knowing; about turning it into elements that can be decontextualized and employed as elements of new epistemic constructions (see below for more detail). These values are inherent in end of school proclamations and policies and can be transformed into ends of its operation by asserting social interaction and integration, knowledge production, confrontation and retention. The recent COVID 19 experience adds a powerful justification to keeping the school as physical place detached from the home, family and pressure of daily routines. What Jan Masschelein and Maarten Simons (Masschelein and Simons, 2013) identified as grounded in the history of scholè (school as free time) has never been so clear before.

However, the return to the common world bound by books and operating as a reading public seems hardly possible nowadays. For the time being, we are happy to use our critical skills to undermine all claims to truth and benevolence (see conspiracy theories around COVID-19 and vaccination policies, cf. Weise, n.d.), and we enjoy our sectarian online commonalities. Not only because we have mastered virtual space to the degree where it has become possible, but because we are mastered by its algorithms as well. Like in Rousseau’s advice given to Emile’s tutor, we are free to do whatever we want, but we want what algorithms want us to want. In Stiegler’s terms we live in the time of permanent innovation when “industrial technical invention has come to outpace conceptual innovation in other social systems such as law, government, and education” (Tinnell, 2015, p. 133). Education has always worked within processes of grammatization where semantically rich signs are separated from their context and turned into particles that can be circulated and articulated into varied semantic chains and processes of “tertiary retention”, of common external memory that works as repository for communication and cultural creations. Modern schools played active role in the grammatization of script, while nowadays this process concerns digital signs. The process is under way and schools try to find ways to address it, but we are far from a significant response, and we usually participate in it as objects rather than responsible actors. What we like on Facebook, or where children put ticks in test sheets are transformed into digital elements of psychographic marketing or political strategies, into school ranks or PISA tables that shape national policies. Education feeds this productive mill and “proletariatizes” students by making them more and more dependent on what the Web knows. Education is implicated in this construction of systemic stupidity (Stiegler, 2015) and fuels tendencies that proclaim the end of school. But it can also turn these resources into culturally productive and socially desirable ends.

This crisis has not arrived with the advancement of the internet and social media, it was already proclaimed after the invention of television (McLuhan, 1994) and, more recently, after the video revolution in the 1980s. There are striking similarities between what Gregory Ulmer (Ulmer, 2004, 2019) was writing about educational uses of video and what Bernard Stiegler says about digital technologies. Both thinkers developed Derrida’s project of grammatology pedagogically. Both say it will take time, just as proliferation of alphabetic script and follow-up technologies had to take their time. When speaking of using camcorders in the classroom Ulmer (2004) said that teachers need to be ready to “speak nonsense” long enough to start seeing sense shining through the chaos. We still do not know what “grammes” (originally, written signs) will we identify in the noise, and what grammatologies will they produce for us and within us. Both Ulmer and Stiegler sooth the panic and say that we are on the path to unprecedented creativity. To arrive there, however, we need a “quantum leap” (Stiegler, 2015) – something that cannot be determined beforehand, definitely not by pressure toward immediate and accountable efficiency.

What next? Let as signal briefly other ends that can be drawn from the school’s ending ontology.

First is ignorance – an issue broader than Stiegler’s stupidity. There are two instances of ignorance that need to be reminded here. Starting with classics, there is Socratic ignorance. Against what dominates in neoliberal knowledge-based policies that seek certainty (evidence-based everything) and silences ambiguity, and against Internet celebrities and conspiracy theories, the virtue of not being sure and the courage to say so sounds like an important starting point for teachers dealing with simple solutions of complex issues and with conspiracy theories that find insidious plots everywhere. This leads us to its instance expressed by Jacques Rancière in his Ignorant Schoolmaster (Rancière, 1991) where teachers who do not know are capable to teach without stultifying outcomes of explication. In his political philosophy, where the distinction between “police” that maintains divisions and distinctions that structure social order and “politics” that disrupts the rules of perceiving the social is fundamental (Rancière, 2015), Rancière says that police regulations need to be ignored when we try to enact emancipated lives. In pedagogical sense ignorance is thus productive when we ignore inequalities that serve “police” distinctions and “distribution of the sensible” with which students enter the school. In practical terms it means that we must make a (counterfactual) assumption that everybody can learn everything without presuming limitations of disqualifying nature. On the other hand, somewhat in line with the remark on Socrates, teachers’ ignorance as to the subject they teach makes it possible to ask the student “what do you think about it” seriously and initiate thinking together. These challenging ideas point to another important issue in the context of this paper: if we indeed live in time of systemic stupidity that is organized and maintained by forces that wage economic war on societies (Stiegler’s term), looking for caveats of ignorance within that war machine is of strategic importance for our chances to change.

Next is rationalism, an idea deeply embedded in modern educational tradition of science education. Teaching scrutiny and methodological rigor is fundamentally significant, and we do not need to seek practical, and economic in particular, justifications to make every effort to make it work at school. However, in contemporary context (e.g., the anti-vaccination movement) it needs to be connected to the value of critical thinking in an extremely attentive way. As Bruno Latour notes, (Latour, 2004) critical competencies may be complicit to proliferation of conspiracy theories. Latour proposes in this context that we redirect our educational efforts from “matters of fact” to “matters of concern” and teach science not for single solutions but calling for more complexity, for density of descriptions, for multifaceted interpretations that confront simplistic explanations of everything, and for arranging education around issues of public concern one cannot remain silent about. A figure of the teacher as rational transversal traveler, one capable of linking heterogeneous elements in a process of interpretation, could be very helpful here.

Following the critical trait, we turn to Jürgen Habermas. If the world is ridden by emotional manipulation and political marketing, and if we still wish to restore the conditions for democracy, we need to teach how to distinguish between truth, rightness, and sincerity. These labels represent what Habermas (Habermas, 2015) calls validity claims. He defined them when discussing ethics of discourse as the condition of democratic deliberation. We can deliberate when we see our interlocutors as speaking truth, as expressing concern with given norms, and as being authentic, or sincere in what they say. Importantly, listening to political campaigners we forget easily that those three claims are of different nature while we must be attentive why we trust them: do they refer to reliable facts? Are they “right” in terms of certain values? Or do they just “look reliable” and “sound sincere”? In the time of political marketing, one must be aware that those who shape our opinion have been professionally trained to look sincere, or they may sincerely believe in lies. Also, we need to remember that what is factual is not always what should be. The fact that those conditions of possibility of democratic deliberation (and thus of decision making) can be manipulated by spin doctors of political campaigns easily means that teaching how to critically distinguish between those features that are inseparable as conditions of democratic dialogue becomes an urgent end in the time when we hear of the end of democracy.

And we have one more suggestion that can be applied right now efficiently. From the grammatological perspective (Derrida, 2016; resp. Ulmer 2004 y 2009; Stigler, 2015) we know that we ourselves are shaped by the media that mediate our relation to the world. How can we therefore gain distance to those media, how do we learn their performative work? First, we have the deconstructive approach that teaches how to gain distance within the text of which we ourselves are part. Another approach, proposed by Szkudlarek (2009), is that we acknowledge the complexity of cultural landscapes where ancient oral, modern literary, and postmodern visual and – across this divide – digital messages operate simultaneously creating nebulous networks of meanings. Distance may be acquired through translation, by expressing one medium in the language of another – a practice well known from schools where we drew pictures to books, we read or made written reports on films we watched. Ulmer proposed that we make films on anything expressed in other media, but we should treat it broadly. Not only is this valuable in terms of gaining distance to new technologies that have enormous potential of simulation and immersion, and thus allowing for under-standing (which always implies substitution or translation), but also because there is always something lost in translation: something that cannot be rendered otherwise. This is where, in residual signifiers that cannot be translated into the known, can we search for “grammes” that compose our yet unknown, but already active futures.

Final (if not ultimate) remarks

We have not proposed a new pedagogy here, or have we invented new roles for teachers. All ideas of which we speak in the concluding section above have been known for long, and we have identified them as operational in the endgames of schooling. However, it was not our aim to be innovative pedagogically. We live in a culture of ending. It has been with us at least from the time of the Apocalypse, it repeated itself with millennial paroxysms frequently, it gained a tragic dimension after the Holocaust and critical self-awareness with postmodernism, it turned tangibly practical with neoliberal reforms, and now it intensifies and crystallizes rapidly in the time of climatic catastrophe. The end is something that lasts, that is, and it will be with us until the end. We have therefore tried to treat frequent claims and some particular cases of the end of school ontologically, to identify values that seem to operate behind this endgame, and to draw ends for schooling and teaching from this condition. If these ends have already been known to pedagogical audiences, we tried to see them with ontological gravity, as embedded in the condition of ending. We will need to stay with this ending condition for long, and if we cannot reverse its logic and return to progressive hope easily, we need to learn how to control the regress before we manage to turn scattered signs and possibilities into new operational grammars of education.

References

Beckett, S., & McDonald, R. (2009). Endgame.

Bendall, M. J., & Robertson, C. (2018). The Crisis of Democratic Culture? International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 14(3), 383-391. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.14.3.383_7

Biesta, G. (2017). The Rediscovery of Teaching. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315617497

Callinicos, A. (1990). Callinicos, A: Against Postmodernism: A Marxist Critique.

Carusi, F. T. (2017). Why Bother Teaching? Despairing the Ethical Through Teaching that Does Not Follow. Studies in Philosophy & Education, 36(6), 633-645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-017-9569-0

Chiş, T. D. (2016). The filter bubble–A constructivist approach. Perspectives in Politics / Perspective Politice, 9(2), 5-11.

Derrida, J. (2016). Of Grammatology. JHU Press.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, Ed.; 1st American Ed edition). Vintage.

Habermas, J. (2015). The Theory of Communicative Action: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, Volume 1. John Wiley & Sons.

Latour, B. (2004). Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern. Critical Inquiry, 30, 225-248. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

Lee, D. (2012). Acta protests: Thousands take to streets across Europe. (2012, March 8). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-16999497

Majewska, D. (2017). Pozytywna Szkoła Podstawowa w Kokoszkach zostaje. “Ważniejsze jest dobro uczniów” [Positive Primary School in Kokoszki stays. “The welfare of the students is more important”]. Trojmiasto.pl. (2017, June 23). http://nauka.trojmiasto.pl/Pozytywna-Szkola-Podstawowa-w-Kokoszkach-zostaje-n114098.html

Masschelein, J., & Simons, M. (2013). In defence of the school. A public issue. E-ducation, Culture & Society.

McLuhan, M. (1994). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Reprint edition). The MIT Press.

Miron, G. & Nelson, C (2002). What’s Public about Charter Schools? Lessons Learnt about Choice and Accountability. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press

Sandbothe, M. (n.d.). The Transversal Logic of the World Wide Web. A Philosophical Analysis. Paper given at the 11th Annual Computers and Philosophy Conference in Pittsburgh (PA). https://www.sandbothe.net/242.html

Nix, A. (2016). Cambridge Analytica - The Power of Big Data and Psychographics. (2016, September 27). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8Dd5aVXLCc

Oliverio, S. (2020). The end of schooling and education for “calamity.” Policy Futures in Education, 18(7), 922–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320944106

Rancière, J. (1991). The ignorant schoolmaster: Five lessons in intellectual emancipation. Stanford University Press.

Rancière, J. (2015). Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (S. Corcoran, Trans.; Reprint edition). Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474249966

Schmitt, C. (2008). The Concept of the Political: Expanded Edition. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226738840.001.0001

Stiegler, B. (2015). States of Shock: Stupidity and Knowledge in the 21st Century. John Wiley & Sons.

Tinnell, J. (2015). Grammatization: Bernard Stiegler’s Theory of Writing and Technology. Computers & Composition, 37, 132-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2015.06.011

Tröhler, D., Popkewitz, T. S., Labaree, D. F., Popkewitz, T. S., & Labaree, D. F. (2011). Schooling and the Making of Citizens in the Long Nineteenth Century: Comparative Visions. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203818053

Ulmer, G. L. (2004). Teletheory. Atropos.

Ulmer, G. L. (2019). Applied Grammatology: Post(e)-Pedagogy from Jacques Derrida to Joseph Beuys. JHU Press.

Vattimo, G. (1991). The End of Modernity: Nihilism and Hermeneutics in Postmodern Culture (Revised edition). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Weise, E. (n.d.). Bill Gates is not secretly plotting microchips in a coronavirus vaccine. Misinformation and conspiracy theories are dangerous for everyone. USA Today News. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2020/06/05/coronavirus-vaccine-bill-gates-microchip-conspiracy-theory-false/3146133001/

Youyou, W., Kosinski, M., & Stillwell, D. (2015). Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(4), 1036–1040. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418680112

Zakrzewski, W. (2014). Ustawa miała ratować małe szkoły. A jak jest? Nauczyciele na umowach o dzieło, a w wakacje - do urzędów pracy [The act was to save small schools. How is it? Teachers on contracts for specific work, and during summer holidays - to employment offices]. Wiadomości. (2014, January 21). http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114871,15306919,Ustawa_miala_ratowac_male_szkoly__A_jak_jest__Nauczyciele.html

Contact address: Maria Mendel. University of Gdańsk, Faculty of Social Sciences. Institute of Education. Uniwersytet Gdański, Wydział Nauk Społecznych, UI. Bażyńskiego 4, 80-309 Gdańsk. E-mail: maria.mendel@ug.edu.pl

1 A first version of this article was presented at the occasion of the international symposium “Exploring What Is Common and Public in Teaching Practices” held online 24 and 25 May 2021 as part of the ongoing activities of the research project #LobbyingTeachers (reference: PID2019-104566RA-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The Spanish translation of this final version has been funded as part of the internationalization strategy of the project.