Neoliberal educational free choice versus the conception of education as a common and public good1

La libre elección educativa neoliberal frente a la concepción de la educación como un bien común y público

DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2022-395-520

Enrique-Javier Díez-Gutiérrez

Universidad de León

Carlos Bernabé-Martínez

Universidad de Murcia

Abstract

This article analyzes the concept of educational freedom in Spain, focusing especially on two of its manifestations, freedom of education and free school choice, as well as its relationship with a conception of education as a common and public good. The objectives have been to analyze the future of its meaning, the main theoretical approaches, its reconstruction in the current social context and the way it relates to a cohesive educational system that extends and guarantees rights and opportunities for all. For this, a systematic review of the literature (SLR) has been carried out, between 1976 and 2020, according to the PRISMA model. Of the 1159 texts reviewed, we have worked on the 47 scientific articles published in open access and that focused specifically on the subject under investigation. The validation was given with the extended criteria of the University of York. The findings reflect that the current notion of educational freedom, linked above all to free educational choice, is closely tied to the defense of the “à la carte” choice of center and teaching model, within the framework of market logics binded to a neoliberal ideology. Thus, freedom of education appears increasingly unrelated to equal opportunities for all and educational equity, and more associated with a tool to avoid social mixing and obtaining socio-labor competitive advantages. In the discussion and conclusions, the way in which the results connect with dynamics of educational neoliberalization is analyzed and the need to continue investigating the deep elements that underlie this experience of freedom is pointed out. There is also the opportunity to explore a republican-oriented approach to educational freedom linked to the common and public good of all and for all.

Keywords: educational freedom; educational equity; educational neoliberalism; common benefit; public good.

Resumen

En este artículo se analiza el concepto de libertad educativa en España, centrado especialmente en dos de sus manifestaciones: la libertad de enseñanza y la libre elección de centro, así como la relación de ambas con una concepción de la educación como bien común y público. Los objetivos han sido analizar el devenir de su significado, las principales aproximaciones teóricas, su reconstrucción en el actual contexto social y el modo en que se relaciona con un sistema educativo cohesionado que extienda y garantice derechos y oportunidades para todos. Para ello, se ha realizado una revisión sistemática de la literatura (SLR), entre el año 1976 y 2020, de acuerdo con el modelo PRISMA. De los 1159 textos revisados se ha trabajado sobre los 47 artículos científicos publicados en acceso abierto y que se centraban específicamente en la temática objeto de investigación. La validación se dio con los criterios ampliados de la Universidad de York. Los hallazgos reflejan que la actual noción de libertad educativa, vinculada sobre todo a la libre elección educativa, se encuentra muy ligada a la defensa de la elección “a la carta” de centro y modelo de enseñanza, en el marco de lógicas de mercado vinculadas a una ideología de corte neoliberal. Así, la libertad de enseñanza aparece cada vez más desligada de la igualdad de oportunidades y la equidad educativa, y más asociada a un instrumento para evitar la mezcla social y obtener ventajas competitivas futuras en clave sociolaboral. En la discusión y conclusiones se analiza el modo en que los resultados conectan con dinámicas de neoliberalización educativa y se apunta la necesidad de seguir indagando los elementos profundos que subyacen a esa vivencia de la libertad. Se plantea también la oportunidad de explorar un enfoque de libertad educativa de orientación republicana ligada al bien común y público.

Palabras clave: libertad educativa; equidad educativa; neoliberalismo educativo; bien común; bien público.

Introduction

Since the last third of the 20th century, much of the planet has witnessed a series of social, cultural, ideological and political transformations associated with neoliberal globalisation (Rendueles, 2020). This process has involved the consolidation of policies aimed at the privatisation of public services, financialisation of the economy, weakening of the welfare state, increased subordination of labour to capital and growing commodification of numerous social spheres (Harvey, 2007).

The neoliberal hegemony is thus not limited to a series of policies and socio-economic changes, but also entails a cultural and mental transformation (Read, 2009) that implies a particular way of thinking about humanity which involves, among other aspects, an “individualistic philosophy essentially focused on the self” and embedded in market logics (Cabanas and Illouz, 2019, p. 62). This “psychologisation of social life” (Parker, 2010, p. 13) compels us to think of ourselves as independent entities, emancipated from any social structure, to such an extent that we increasingly view ourselves as consumers (Moruno, 2018) rather than citizens.

Neoliberalism, therefore, is not only the ideological theory that currently underpins and sustains capitalism, but is also the generator of a social vision, a way of living and relating, a “regime of truth” (Foucault, 2004), a “common sense” (Gramsci, 1981) of shared worldviews, and a particular type of subjectivity (Díez-Gutiérrez, 2018). Michel Foucault (1975) observed that contemporary Western societies have abandoned the disciplinary model of social control to adopt more subtle and refined tools of social control that require the “victims” themselves to accept and even actively collaborate and participate in it (Han, 2012; Hardt & Negri, 2002).

The neoliberal model establishes the “obligation to choose” as the “logical rule of the game”, in a life governed by market dictates (Laval and Dardot, 2013). Freedom of choice, in terms of selecting the most advantageous option from among a range of offers and maximising self-interest, has thus become one of the basic tenets of the new forms of behaviour. The State is expected to strengthen competition in existing markets and create competition where it does not yet exist. Consequently, the dominant notion of freedom in the current historical period is closely connected to the negative liberty defined by Isaiah Berlin (Carter, 2010), but in a context of global commodification.

The prevailing image under neoliberal subjectivity is that of “individual freedom but not political freedom” (Villacañas, 2020, p. 105), which is exercised within a market logic. Furthermore, this freedom is blind to social structures, the material conditions of life and the relations of domination that underlie it and influence our behaviour (Beauvois, 2008). Under this ideological umbrella, the experience of freedom implies the paradoxical aspiration to maximise non-interference with the individual’s desire, while at the same time the individual minimises his or her political freedom to intervene in the social structures and relations that dominate and condition him or her.

This substantial shift was evidenced by Margaret Thatcher’s (1987) notorious observation in a now famous interview when reflecting on the concept of society: “There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families”. Her negation envisages a social reality viewed not as a constellation of shared structures that determine our life opportunities, but as the sum of individual wills divorced from any kind of social power structure that conditions them.

Thus, if neoliberalism implies a profound change in the economic and social playing field and in the subjectivity and desires of those who participate in it (Han, 2012), it is worth investigating how this affects the sphere of education and how this sphere, in turn, actively participates in this shift. The late 20th century witnessed the emergence of a global trend towards the privatisation of education systems (Verger, Zancajo, and Fontdevila, 2016) and the commodification of the “educational economy” (Ball, 2014). This process, from which Spain has not been exempt (Bernal and Lacruz, 2012), has led to the increased involvement of private actors –especially business– in the provision of education services. In addition, “market mechanisms” (Bonal and Verger, 2016) and “business logic” have been incorporated into education (Rodríguez, 2016), often accompanied by a model of educational philanthrocapitalism (Saura, 2016) linked to Big Tech digital platforms (Saura, 2020).

The effect of neoliberalism on the Spanish education system has been to shift the central principles and policies of education towards a vision based on market dynamics and culture. Management and administration tools more properly associated with private companies have been incorporated into schools, individualising goals and rewards and transforming families into “school consumers” seeking to maximise their opportunities. Competition is encouraged between schools as these vie for higher positions in the rankings, while school management practices driven by performance targets oblige teachers to compete with each other and convert “star teachers” into marketing products. Hence, competition becomes a way of internalising the demands of profitability, while at the same time generating disciplinary pressure via increased workloads, shortened deadlines and the individualisation of wages, undermining forms of collective solidarity in education communities (Díez-Gutiérrez, 2018).

This neoliberal approach entails a progressive shift whereby education is increasingly viewed as a commodity and less and less as a right, and is managed, organised and regulated more as a business than as a public service. The purpose, principles and objectives of education have been increasingly linked to market demand, to the detriment of the integral development of students or the needs of the social community in a broad democratic sense. Such transformations clash with the concept of education as a common good, which assumes, as Cascante (2021) argues, that education does not spring solely from individuals as the subjects of rights, but also from the community. Thus, beyond individual rights operating in the field of education, commonly agreed democratic interests must be safeguarded, because education arises from the community and the community must therefore benefit from it. Hence, it can be argued that the way in which educational freedom is conceptualised or addressed will also affect the possibilities for education to be not only a public good, but also a common good (UNESCO, 2015).

The present research analyses the interface between freedom of education and school choice. Historically, freedom of education has formed a core element of educational debate in Spain, both at the time of establishing the 1978 Constitution (González and Hernández, 2018) and throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries (Gómez, 1983). In recent years, however, the demand for such freedom has gained renewed strength. Educational freedom has to a greater or lesser extent penetrated several debates as the main argument. Thus, freedom of education and school choice have played an enormous role in the debates surrounding the education laws passed in the 21st century (Briones and Oñate, 2021; Vintanel, 2017) and more specific, regional controversies such as the so-called parental PIN or educational veto in the Regions of Murcia and Andalusia (Climent, 2020; Fernández, 2020) and the laws on plurilingualism in the Region of Valencia (Alonso and Pérez, 2018; García, 2015).

This creates the need to analyse what kind of freedom is projected onto and from education and determine whether the educational sphere is thought of from the perspective of negative liberty in a context of growing commodification and individualism (the freedom, for example, to choose a school or a type of education without interference from third parties, whether the community or the State) or from a positive, republican perspective that assumes educational freedom is based on an egalitarian distribution of power that enables the various agents involved to intervene democratically in this sphere.

Method

This article analyses recent shifts in the concept of educational freedom in Spain and explores how these have impacted on the education system and will continue to affect it in the face of future challenges.

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted of research and publications related to the subject under study: freedom of education and school choice. The specific objectives were: (a) to identify the main theoretical approaches to the concept of educational freedom, understood as freedom of education and school choice; (b) to analyse the dominant meanings and implications for educational practice; and (c) to contribute to debate on the purpose of the Spanish education system today.

The review was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) guidelines for a systematic review (Moher et al., 2009; Urrútia and Bonfill, 2010), enabling us to avoid, or at least minimise, possible biases (Moraga and Cartes-Velásquez, 2015).

Publications considered for inclusion comprised peer-reviewed scientific articles based on quantitative and/or qualitative methods, literature reviews and essays. References were identified by searching databases using the most suitable, relevant and frequent search terms (see Table 1) employed to refer to the subject in Spain.

Scopus, Dialnet and Web of Science (WOS)2 were systematically searched for all documents published between 1976 (beginning of the transition to democracy) and 2021 (present day), using Boolean operators. The content of the selected articles was read and analysed before mapping the current state of the question.

TABLE 1. Search strategy

|

Database |

Keywords |

Boolean operators |

Search results |

|

SCOPUS |

“school choice” [libertad de elección educativa] |

AND |

158 |

|

“freedom of education” [libertad de enseñanza] |

AND |

173 |

|

|

DIALNET |

“school choice” [libertad de elección educativa] |

AND |

428 |

|

“freedom of education” [libertad de enseñanza] |

AND |

314 |

|

|

WOS |

“school choice” [libertad de elección educativa] |

AND |

83 |

|

“freedom of education” [libertad de enseñanza] |

AND |

3 |

|

|

Total |

1159 |

Note: Table by the authors.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Publications about experiences or studies in Spain or in Spanish schools.

- The area of knowledge falls within the social sciences, teaching and education.

- Open access documents.

- The subject matter of the publications specifically includes the research subject and does not focus on related but tangential subjects such as academic freedom, civil liberties education or freedom during the educational process.

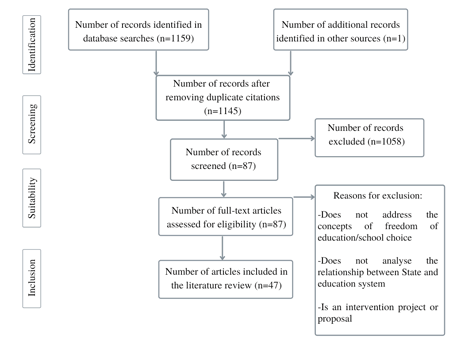

In the first screening, we read the titles and abstracts and scanned the article contents, excluding any which (a) did not report an explicit approach to the concept of freedom of education and/or school choice, in the sense defined in our research; (b) did not report an analysis of the education system that rendered explicit a particular vision of freedom of education or school choice; or (c) reported intervention projects or proposals. After applying these criteria to the total of 1159 articles identified in the database search and excluding duplicates, 47 papers were selected for the systematic literature review. Fig. 1 summarises the process.

FIGURE 1. Prisma Flow Diagram 2009 (Spanish version)

Note: Diagram adapted from Moher et al. (2009).

This initial screening yielded an overview of the research subject, shedding light on the main political and epistemological approaches in recent times to the concepts of freedom of education and school choice, their implications for the Spanish education system and their associated values and elements. In our view, these empirical results will contribute to a better interpretation of the current debate on education and to critical reflection on the limits and potential of the Spanish education system.

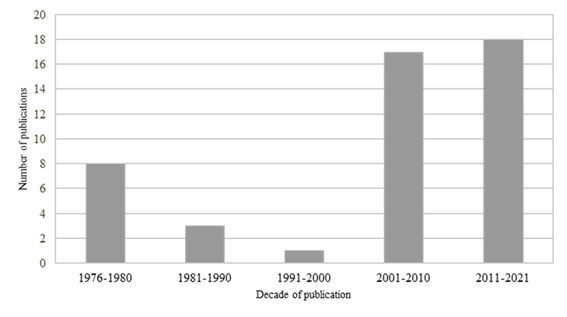

Extended University of York criteria (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009) were applied for validation: study inclusion and exclusion criteria, relevance and appropriateness, quality assessment, data description, currency, impact and sufficiency. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have already been given above in the section describing the screening process. Relevance and appropriateness were ensured by identifying those studies that were most relevant to the research subject. Quality assessment and data description refer to the validity and soundness of the research method employed and the robustness of the data obtained. The criterion of time is aimed at obtaining a diachronic perspective of the research subject. The criterion of currency was met by including significant contributions from the 1970s to the present, retrieving the most recent advances in the field. Figure 2 shows the number of articles selected by decade of publication. With regard to the criterion of impact, all articles reviewed were published in prestigious, high-impact, peer-reviewed journals. Fulfilment of the sufficiency criterion was satisfactory, with the final inclusion of 47 publications.

FIGURE 2. Decade of publication of the articles included in the literature review

Note: Table by the authors.

The process employed was sequenced as follows. Having selected the publications that met the study criteria using the Mendeley reference manager, a coding guide was drawn up using the Microsoft Excel software program, detailing the criteria for coding the characteristics of the studies reported in the selected articles, in accordance with the specific objectives of this review. The sections on objectives, methods, results and conclusions of the articles were reviewed in order to extract the following information identified in the categories: year of publication, authors, author affiliation (university or non-university), journal quality in rankings, type of study (intervention, descriptive-empirical or theoretical), methods used, sample, data collection sources, results and conclusions according to the specific objectives of the present literature review, proposals or recommendations and limitations given. We also included the defining framework of educational freedom –freedom of education and school choice– as a category of analysis. These categories were established in a verification protocol that was applied to each document.

An analysis of these articles revealed an interesting distribution over time, whereby the preliminary results, screening and relevance criteria all indicated a high concentration of publications in the late 1970s, followed by a significant decline that was reversed in the early 21st century and has continued to the present day (see Figure 2). We believe this distribution reflects debate at the time of writing and adopting the Spanish Constitution over its article 27 referring to freedom of education, which was one of the most controversial and contentious provisions (Villamor, 2007; Mayordomo, 2002), followed by renewed interest in this question in response to subsequent legislative modifications: LOE (Organic Law on Education) in 2006, LOMCE (Organic Law to Improve Educational Quality) in 2013 and LOMLOE (Organic Law modifying the LOE) in 2021 (Briones & Oñati, 2021; Celador, 2016; Guardia, 2015; Vidal 2017).

Results

In relation to the first of the study objectives, we identified two main, broad categories of theoretical approaches to the concept of educational freedom: one based on a legal, historical or philosophical-political perspective, encompassing general reflections on the meaning of education or specific applications (school choice, academic freedom, homeschooling, single-sex education), and a second focused on educational freedom in terms of school choice, analysing implementation in given contexts. These approaches enabled us to explore the way in which different disciplines enter into dialogue and determine, from different angles, the state of our research subject.

First, a review of texts analysing the evolution of the concept or its topicality at different times revealed a historical shift in use of the concept of educational freedom. In the 19th century, in countries such as France, freedom of education (in terms of the freedom of private entities to create schools and the freedom of families to choose education in accordance with their convictions) was the banner under which the clergy united to combat the advance of public instruction (García, 2018; Puelles, 1993), whereas in Spain, the situation was to some extent the reverse, and freedom of education became one of the central demands of liberal sectors in order to guarantee a counterpoise in civil society to a State strongly dominated by clerical and conservative sectors (Hernández-Díaz, 1982; Martín, 2008; Molero, 2005; Vilanou, 1982). This discursive logic was to change during the 20th century, especially from the Second Republic onwards, when educational freedom, associated with the freedom of families to create schools and choose their educational model, became a demand that was closely linked to the defence of religious education and conservative private initiative (Gómez, 1983). As we shall see below, this interpretation of freedom became one of the main arguments in demands for an agreement on State-subsidised private schools after the dictatorship.

Between the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the context of the constitutional process, the debate on educational freedom was clearly central in various publications. The common thread running through all of them was a vindication of this freedom as a means to defend religious freedom (González del Valle, 1979) and “the rights of the Church in the field of education” (Guzmán 1979, p. 180) associated with the Concordat between Spain and the Vatican, and thus counter the risk that the democratic regime would lead to greater State influence –or even a monopoly– in education through State schools (Gómez, 1979; Hengsbach, 1979). According to this approach, such freedom would only be possible by maintaining a “progressive critical distrust of the State”, as Gómez argued (1979, p. 137), and by guaranteeing the “right to freely establish and govern educational establishments” and the “preferential right of parents or guardians to elect the education of their choice for their children” (Martínez, 1979, p. 217). Furthermore, there was a demand that such “freedom” not be reduced to a mere “formality” because of lacking the “real conditions” (Orlandis, 1979, p. 117) or “economic means” (García-Hoz, 1979, p. 39) to render it viable, nor should it be subordinated to the development of the public education system (Hervada, 1979). In other words, an early defence appears to have emerged of what would become the agreement on State-subsidised private schools, whose main beneficiary was the Catholic Church, which today still controls six out of every ten such schools (Fayanás, 2018; Rogero-García and Andrés-Candelas, 2014).

Subsequent approaches in the 21st century evidenced more clearly the conjunction of the three elements that seem to be most strongly linked to freedom of education: the freedom to create schools reflecting a particular ideology, the freedom of families to choose a school and educational model, and to a lesser extent, academic freedom (Guardia, 2019; Llano, 2006; Vidal, 2017). With regard to the first two (school creation and school choice), Viñao (2019) observed that these eventually became part of the dominant interpretation of the freedom of education established in article 27 of the Spanish Constitution, despite its ambivalence.

On numerous occasions, this specific meaning of freedom of education has been used to argue in favour of the system of State-subsidised private schools (Guardia, 2015), single-sex education (Báez, 2019; García-Gutiérrez, 2004) and homeschooling as extensions of this freedom (Llorent-Bedmar, 2004; Monzón, 2011). Thus, the right to education and freedom of education emerge more as opposing elements to be balanced (Hernández, 2008; Murgoitio, 2018) than as complementary components.

We also found critical approaches that explicitly distinguished between freedom of education and freedom in education, although they continued to associate the former with “private initiative”, while the latter was associated with “civic freedoms in the field of teaching”, “academic freedom” and “participation of the school community” without any “ideological dirigisme by the public authorities” (Dutra, 2002, p. 4). Within this approach, Prieto and Villamor (2018) have argued that in the current context, “the reference to school choice is, therefore, a narrowing of the consideration of freedom in education (...) The use of this meaning of freedom implies an economic conception of education” (p. 24).

A constant feature observed in the review was related to mistrust or rejection of the State in the field of education, which was articulated in various ways: rejecting the State’s educational monopoly as being incompatible with pluralism (Guardia, 2019; Murgoitio, 2018); desiring less interference by the “State in the education of families” (Llano, 2019); and associating the State’s greater influence in education with dynamics opposed to freedom (Blanco, 2009) or tending towards “neutralising nihilism” (Llano, 2006, p. 183).

This stance reflects a demand that public education be “ideologically neutral”, arguing that it is the ideologies of private schools that will guarantee social and educational pluralism (Celador, 2016). Besides the difficulties in defining the concept of neutrality (Llano, 2019) and the fact that all “education is political” (Carbonell, 2019), this line of reasoning demands the absence of ideology on the part of the public authorities while at the same time defending the right to opt for a particular ideology in the private sphere. According to this approach, freedom of education is not constructed through the plurality of teachers in State schools, but by creating the possibility –only available to a limited segment of the population– of escaping from the public education system.

Such an argument reflects the increasing penetration of market dynamics (Andrada, 2008) or “quasi-market” systems (Maroy, 2008) in education, which involves the creation of an educational offer that places certain families in the position of exercising “their freedom”, mainly through the “choice of school”, assuming the role of consumers (Olmedo-Reinoso and Santa Cruz, 2008). This very different approach to “freedom” has witnessed an unprecedented surge in popularity in recent years, and is propounded by conservative and neoliberal sectors that view education as an investment, students and families as customers and the educational authorities as a mere regulatory body between agents and investors, and claim to offer “free choice” in a markedly asymmetrical and unequal scenario for all families in terms of cultural capital, income and information (Bernal and Veira, 2019; Sanz-Magallón et al., 2021; Villarroya and Escardíbul, 2008).

Our literature review also revealed that since the late 20th century, educational freedom seems to have become more associated with a defence of freedom of choice under market logics, and much less with a concern for religious or moral questions, as if there had been a shift from the pulpit to the marketplace. Indeed, some of the recent studies examining the question of religion in education do not even include an in-depth discussion of the concepts of freedom of education or school choice (Jiménez, 2011; Sanjurjo, 2013). Thus, freedom of choice appears to be increasingly linked to issues related not so much –or not exclusively– to the denominational or ideological nature of State-subsidised private schools, as to the possibility of seeking competitive socio-economic and cultural advantages. Examples include the possibility of escaping from depressed areas (Bernal and Vera, 2019; Valiente, 2008), “taking refuge” from educational or social problems (Fernández and Muñiz, 2012; Rodríguez et al, 2014; Rogero-García and Andrés-Candelas, 2014), maintaining middle-class status (Andrada, 2008) and accessing better “educational quality” based on a school’s “reputation” (Peláez-Paz, 2020).

From this it can be inferred that within the obvious plurality of approaches to educational freedom, the “package of freedoms” (Llanos, 2006 and 2019) that it represents seems at present to have condensed around the freedom to create privately owned schools and for families to choose an educational model in accordance with their personal convictions. Moreover, this interpretation is located in a context of increasing commodification of education, social inequality and rejection of the State and public authorities as an element of cohesion. These three factors (narrowing of freedom of education, rejection of the State and commodification of the education system) provide a glimpse, in relation to the second of the study objectives, of the consolidation and possible dominance of a neoliberal interpretation of educational freedom. Such a framework would necessarily imply the commodification of relations in education, not only in terms of content, management and organisation of schools, but also in terms of the roles, desires and relations of their actors (Cascante, 2021).

Discussion and conclusions

It is evident that the concept of freedom of education has coalesced in its neoliberal sense within the context of an increasingly commodified education system. Meanwhile, for some of the critical positions, the debate resides in how to correct its less desirable effects, such as segregation or discrimination, without questioning the premise that the less interference from the public authorities (beyond setting minimum educational standards), the greater the freedom of education (Sainz and Sanz, 2021).

There are some contradictions in this framework. On the one hand, the right to choice of school can never be universal without absolute equality of conditions for families to select from an infinite educational offer. The evidence, however, seems to point in the opposite direction, towards a “segregation” effect (Andrada, 2008; Fernández, 2008; Gómez, 2019; Madaria and Vila, 2020; Mancebón and Ximénez, 2007; Murillo et al., 2021; Olmedo-Reinoso and Santa Cruz, 2008; Pérez, 1998; Sainz and Sanz, 2021), because such freedom of choice often excludes or does not exist for a large part of the population that lacks sufficient material conditions to exercise it. Furthermore, as Pérez (1998) has observed, in several instances, freedom of education has increasingly been interpreted to mean the “freedom to impose the school’s ideology” (p. 142). In other words, rather than reflecting a desire to broaden the diversity of educational options by increasing the variety of choices available to all families regardless of their social status, this demand for greater freedom of education instead serves as a means to guarantee that a school’s given ideological framework or ideology will be maintained by its owners.

Second, the freedom of education associated with the creation of schools governed by a particular ideology operates in a context where the resources necessary to create such schools are unevenly distributed and the number of sectors with the actual capacity to create such schools (whether or not these are partially supported by the State) is consequently limited. Thus, the education system that actually exists is not based on a wide range of educational options from which families select that which most closely reflects their aspirations or values. On the contrary, the landscape indicates that most alternative options to State schools fall within one particular ideological and denominational sector. Furthermore, such choice is often not so much a choice of ideology as a desire to maintain status or avoid precarious educational environments. The freedom to create and choose a school, as proposed in the Constitution as a safeguard clause for a particular ideology and religious affiliation, now seems to have become an excuse for perpetuating an eminently discriminatory model.

Thus, we consider it important to insert into the academic debate the way in which neoliberal educational freedom is closing the doors to an exploration of a republican meaning of educational freedom (Garzón and Díez-Gutiérrez, 2016), defining republican freedom as that which aspires to an “absence of domination” (López de Robles, 2010) and which does not derive from the mere absence of State or third party interference but is the result of a political and democratic intervention that guarantees the existence of reciprocally free subjects who do not need “permission to navigate civil life” (Domènech, 2019). If measures aimed at commodifying education generate dynamics of segregation that systematically affect and exclude the most vulnerable sectors or those with the least resources, we may not be dealing with a model that is dysfunctional as such, but rather with its inevitable consequences.

An alternative approach would be to think about freedom of and in education not as the right to choose a school or educational model in a competitive, commodified scenario governed by a privatised and individualised vision of education, but as the result of democratic political intervention.

This would imply exploring legal, political, and educational mechanisms that guarantee freedom of choice of educational model through the effective participation of families, students and the education community in the dynamics of the schools themselves, as established in the Constitution and in the definition of the regulatory frameworks that govern the teaching-learning process. Educational freedom does not appear here as the fiction of individual (or family) emancipation from a common educational space, based on self-interest, but as the effective possibility of participating in and co-governing the construction of this collective space for the common good and betterment of all.

This will entail projecting a sense of freedom of and in the educational sphere as a result of the material possibility of “participating on equal terms” (Rendueles, 2020). It will be necessary to propose mechanisms that endow sufficient autonomy to civil society, in the framework of a public education system that is more permeable to the needs and particularities of each community and where freedom refers not to choose of school and type of education, but to jointly constructing a democratic education in a shared project.

The public education system should not be seen as a sort of equitable counterweight to the excesses of “genuine freedom” guaranteed by the private sphere, but as a privileged instrument to convey educational freedom, guaranteeing equal conditions and critical autonomy for students, teachers, and families.

This brings us to the second element for discussion, namely the way in which the neoliberal interpretation of freedom is framed as the right of families to choose an educational model for their children. This choice is posited as the result of a private, individual act in an increasingly commodified context. But which scenario offers more freedom? The possibility of electing an educational model through choice of school, in a commodified context conditioned by material limitations such as distance, income or cultural capital, or the guarantee of being able to participate on equal terms with reciprocally free subjects (Domènech, 2019) in shaping the conditions of the educational model itself? In other words, (republican) freedom would derive from the ability to participate in, shape and allocate resources to the education system, free of relations of subalternity derived from economic or political inequality, and articulated in ways other than a market, private and competitive logic.

It may be worthwhile therefore to investigate the fundamental elements underlying the educational community’s experience of freedom. Besides the immediate strategies or interests that motivate people to opt for one school or another, what deep needs and concerns underlie their decisions? Can these be met by another educational model based on a public education system common to the entire population? Can this educational freedom be inserted into decision-making spaces other than simply opting for one school over another based on a commercial logic? There is a need for research focused not only on how society behaves in a “quasi-market” educational environment, but also on how society’s needs and interests can be addressed by an educational model capable of ensuring freedom of and in universal public education, and providing a guarantee of the equity and cohesion from which we have been drifting away.

References

Alonso, M., & Pérez, M.A. (2018). O plurilingüismo na escola infantil. Eduga, 75, 36-42.

Andrada, M. (2008). Libertad de elección escolar, mecanismos de atribución de plazas y preferencias familiares: una evaluación a partir de criterios de equidad. Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 20-62.

Báez, R. (2019). Hacia la consolidación de la constitucionalidad de la educación diferenciada. A propósito de la sentencia del tribunal constitucional 31/2018. Revista de Derecho Político, 105, 251-278. https://doi.org/10.5944/rdp.105.2019.25274

Ball, J. (2014). Globalización, mercantilización y privatización: tendencias internacionales en Educación y Política Educativa. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 22(41), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n41.2014

Beauvois, J-L. (2008). Tratado de la servidumbre liberal. Análisis de la sumisión. La oveja roja.

Bernal, J. L., & Lacruz, J. L. (2012) La privatización de la educación pública. Una tendencia en España. Un camino encubierto hacia la desigualdad. Profesorado. Revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 16(3), 103-131.

Bernal, J. L., & Veira, C. (2019). La elección de centro como mecanismo de segregación social. Revista Fuentes, 21(2), 189-200. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2019.v21.i2.04

Blanco, M. (2009). La libertad educativa y los estudios universitarios. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 67(244), 475-494.

Bonal, X., & Verger, A. (2016). Presentación: Privatización educativa y globalización: una realidad poliédrica. Revista de Sociología de la Educación-RASE, 9(2), 175-180.

Briones, I. M., & Oñate, M. A. (2021). La aventura de la LOMLOE. un acercamiento a la Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de educación. Revista General de Derecho Canónico y Derecho Eclesiástico del Estado, 55, 3-11.

Cabanas, E., & Illouz, E. (2019). Happycracia. Cómo la ciencia y la industria de la felicidad controlan nuestras vidas. Paidós

Carbonell, J. (2019). La educación es política. Octaedro.

Carter, I. (2010). Libertad negativa y positiva. Astrolabio: Revista Internacional de Filosofía, 10, 15-35.

Cascante, C. (2021) La educación como bien común. En E. J. Díez-Gutiérrez, & J. R. Rodríguez-Fernández (Ed.) Educación crítica e inclusiva para una sociedad poscapitalista (pp.151-164). Octaedro

Celador, Ó. (2016). Derecho a la educación y libertad de enseñanza en la LOMCE. Derechos y Libertades, 35, 185-214. https://doi.org/10.14679/1032

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (Ed.) (2009). Systematic Reviews. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. CRD, University of York.

Climent, J.A. (2020). El PIN parental y la jurisprudencia del TEDH. Actualidad jurídica iberoamericana, 13, 102-121.

Díez-Gutiérrez, E.J. (2018). Neoliberalismo educativo. Octaedro.

Domènech, A. (2019). El eclipse de la fraternidad. Una revisión republicana de la tradición socialista. Akal

Dutra, C. C. (2002). La privatización de la educación pública: una violencia social. Revista Electrónica interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 5(2), 1-4.

Fayanás, E. (2018, Marzo 5). La educación privada concertada, el poder de la Iglesia. Público. https://cutt.ly/7QG0JKn

Fernández, M. (2008). Escuela pública y privada en España: La segregación rampante. Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 1-27.

Fernández, R., & Muñiz, M. (2012). Colegios concertados y selección de escuela en España: un círculo vicioso. Presupuesto y gasto público, 67, 97-118.

Fernández, V. (2020). La Constitución es gramaticalmente perfecta (y el pin parental, un espantajo). CLIJ, 33(294), 5.

Foucault, M. (1975). Vigilar y Castigar. Ediciones Siglo XXI.

Foucault, M. (2004). Naissance de la biopolitique. Cours au Collège de France (1978-1979). Seuil/Gallimard.

García-Hoz, V. (1979). La libertad de educación y la educación para la libertad. Persona y Derecho, 6, 13- 55. https://hdl.handle.net/10171/11930

García-Gutiérrez, J. (2004). Igualdad de oportunidades entre los sexos y libertad de enseñanza. Una aproximación desde la política de la educación. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 62(229), 467-482.

García, J. V. (2015). El plurilingüismo y la educación valenciana. Miríada hispánica, 10, 23-44.

García, R. (2018). Iglesia y Estado en el siglo XIX francés: Tocqueville y la libertad de enseñanza. Historia Constitucional, 19, 533-564. https://doi.org/10.17811/hc.v0i19.527

Garzón, A., & Díez-Gutiérrez, E. J. (2016). La educación que necesitamos. Akal.

Gómez, R. (1979). Las contradicciones de la libertad de enseñanza. Persona y Derecho, 6, 121-140. https://doi.org/10.15581/011.6.121-139

Gómez, G. (1983). Derecho a la Educación y Libertad de Enseñanza. Naturaleza y Contenido. Revista Española de Derecho Constitucional, 7, 411.

Gómez, J. M. (2019). Zonificación escolar, proximidad espacial y segregación socioeconómica: los casos de Sevilla y Málaga. REIS: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 168, 35-54. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.168.35

González del Valle, J. M. (1979). Libertad de enseñanza en materia religiosa y su plasmación legal. Persona y Derecho, 6, 427-447.

González, S., & Hernández, J.L. (2018). La libertad de enseñanza en la opinión pública durante la transición a la democracia en España. Educació i Història, 32, 173-198.

Gramsci, A. (1981). Cuadernos de la cárcel (vol. 2). Era.

Guardia, J. J., & Manent Alonso, L. (2015). La cesión de suelo público dotacional para la apertura de centros docentes concertados: una nueva manifestación del estado garante. Revista Catalana de Dret Públic, 51, 174-190. https://doi.org/10.2436/20.8030.01.60

Guardia, J. J. (2019). Marco constitucional de la enseñanza privada española sostenida con fondos públicos: recorrido histórico y perspectivas de futuro. Estudios Constitucionales, 17(1), 321- 362.

Guzmán, I. (1979). Fundamentos filosófico-sociales de la educación. Persona y Derecho, 6, 171-192. https://doi.org/10.15581/011.6.171-191

Han, B. (2012). La sociedad del cansancio. Herder.

Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2002). El Imperio. Paidós.

Harvey, D. (2007) Breve Historia del Neoliberalismo. Akal

Hengsbach, F. (1979). Libertad de enseñanza y derecho a la educación. Persona y Derecho: Revista de Fundamentación de Las Instituciones Jurídicas y de Derechos Humanos, 6, 57-108. https://hdl.handle.net/10171/12383

Hernández-Díaz, J. M. (1982). La libertad de enseñanza en la restauración y su incidencia en la Universidad de Salamanca. Historia de La Educación Revista Interuniversitaria, 3, 109-126.

Hernández, J. C. (2008). La educación en la Constitución Española de 1978. Debates parlamentarios. Foro de Educación, 10, 23-56.

Hervada, J. (1979). La libertad de enseñanza: principio básico en una sociedad democrática. Ius Canonicum, 19(37), 233-242.

Jiménez de Madariaga, C. (2011). Pluralismo religioso y educación. ARBOR Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura, 749, 617-626. https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2011.749n3013

Laval, Ch., & Dardot, P. (2013). La nueva razón del mundo. Ensayo sobre la sociedad neoliberal. Gedisa.

Llano-Torres, A. (2006). Amantes de la libertad humana hasta el riesgo, no ávidos controladores del sistema educativo. Foro: Revista de ciencias jurídicas y sociales, 4, 153-188.

Llano-Torres, A. (2019). Una revisión de la teoría de la escuela pública neutral en España. Revista de Estudios Políticos, 183, 101-128. https://doi.org/10.18042/cepc/rep.183.04

Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2004). Libre elección de educación obligatoria en el ámbito de la Unión Europea: el cheque escolar y la escuela en casa. Revista de Educación, 335, 247-272.

López de Robles, L. (2010). La concepción republicana de la libertad en Pettit. Un recorrido histórico por Hobbes y Locke. Ingenium, 3, 119-138.

Madaria de, B., & Vila, L. E. (2020). Segregaciones Escolares y Desigualdad de Oportunidades Educativas del Alumnado Extranjero en València. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 18(4), 269-299. https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2020.18.4.011

Mancebón, M. J., & Ximénez, D. P. (2007). Conciertos educativos y selección académica y social del alumnado. Hacienda Pública Española, 180, 77-106.

Maroy, C. (2008). ¿Por qué y cómo regular el mercado educativo? Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 9-19.

Martín, B. (2008). Enseñanza pública y enseñanza privada ¿conflicto o complementariedad? Foro de Educación, 10, 111-132.

Martínez, J. L. (1979). La Educación En La Constitución Española (derechos fundamentales y libertades públicas en materia de enseñanza). Persona y Derecho, 6, 213-214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15581/011.6.215-295

Mayordomo, A. (2002). La transición a la democracia: educación y desarrollo político. Historia de La Educación: Revista Universitaria, 21, 19-47.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., & The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Molero, A. (2005). Influencias europeas en el laicismo escolar. Historia de La Educación: Revista interuniversitaria, 24, 157-177.

Monzón, M. (2011). La educación en casa o homeschooling: la STC de 2 de diciembre de 2010. Revista sobre la infancia y la adolescencia, 1, 121-126. https://doi.org/10.4995/reinad.2011.858

Moraga, J., & Cartes-Velásquez, R. (2015). Pautas de Chequeo, parte II: QUOROM y PRISMA. Revista Chilena de Cirugía, 67(3), 325-330. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-40262015000300015

Moruno, J. (2018). No tengo tiempo. Geografías de la Precariedad. Akal.

Murgoitio, J. M. (2018). El sistema educativo, entre el monopolio y la libertad escolar: escuela plural o pluralidad de escuelas. La letra y el espíritu de la Constitución. Ius Canonicum, 115(58), 83-120. https://doi.org/10.15581/016.115.001

Murillo, F. J., Almazán, A., & Martínez-Garrido, C. (2021). La elección de centro educativo en un sistema de cuasi-mercado escolar mediado por el programa de bilingüismo. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(1), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.68068

Olmedo-Reinoso, A., & Santa Cruz, E. (2008). Las familias de clase media y elección de centro: el orden instrumental como condición necesaria pero no suficiente. Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 165-195.

Orlandis, J. (1979). El derecho a la libertad escolar. Persona y Derecho, 6, 109-120.

Parker, I. (2010). La psicología como ideología. Contra la disciplina. Catarata: Madrid.

Peláez-Paz, C. (2020). La influencia de la fama de las escuelas en la elección de centro escolar de las familias: un análisis etnográfico. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 32(2), 131-155. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.22394

Pérez, A. I. (1998). La cultura escolar en la sociedad neoliberal. Morata.

Villarroya, A., & Escardíbul, J. O. (2008). Políticas públicas y posibilidades efectiva de elección de centro en la enseñanza no universitaria en España. Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 90-115.

Prieto, M., & Villamor, P. (2018). El Impacto de una Reforma: Limitación de la Autonomía, Estrechamiento de la Libertad y Erosión de la Participación. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 26(63), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3255

Puelles de, M. (1993). Estado y Educación en el desarrollo histórico de las sociedades europeas. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 1, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie103006

Read, J. (2009). A genealogy of homo-economicus: Neoliberalism and the production of subjectivity. Foucault studies, 6, 25-36. https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i0.2465

Rendueles, C. (2020). Contra la igualdad de oportunidades. Seix Barral.

Rodríguez, V., Pruneda, G., & Cueto, B. (2014). Actitudes de la ciudadanía hacia los servicios públicos. Valoración y satisfacción en el periodo 2009-2011. Política y Sociedad, 51(2), 595-618. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_POSO.2014.v51.n2.43561

Rodríguez, J. R. (2016). El discurso neoliberal en política social y educativa. Consecuencias. Alternativas. Editorial Académica Española.

Rogero-García, J., & Andrés-Candelas, M. (2014). Gasto público y de las familias en educación en España: diferencias entre centros públicos y concertados. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 147, 121-132. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.147.121

Sainz, J., & Sanz, I. (2021). Los centros públicos y concertados se refuerzan mutuamente. Revisión de la Literatura. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 516, 16-20.

Sanjurjo, V. A. (2013). Estado constitucional y derecho a la libertad religiosa: especial atención a la manifestación de símbolos religiosos en el ámbito educativo. Dereito: Revista Xurídica da Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 1, 653-672.

Sanz-Magallón, G., López Martín, E., & Reyero, D. (2021). Relaciones entre libertad de educación, rendimiento y equidad educativa. Comparativa internacional. En, P. Santos Rodríguez (Ed.) La libertad de educación: un análisis interdisciplinar de sus presupuestos y condicionamientos actuales (pp. 307-334). Tirant lo Blanch

Saura, G. (2016). Neoliberalización filantrópica y nuevas formas de privatización educativa: La red global Teach For All en España. Revista de Sociología de la Educación-RASE, 9(2), 248-264.

Saura, G. (2020). Filantrocapitalismo digital en educación: Covid-19, UNESCO, Google, Facebook y Microsoft. Teknokultura, 17(2), 159-168. https://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.69547

Thatcher, M. (1987). Interview for Woman’s Own (‘no such thing as society’). Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Online: www. margaretthatcher. org/document/106689.

UNESCO. (2015). Replantear la educación. ¿Hacia un bien común mundial? Ediciones UNESCO. https://cutt.ly/MQG4JSw

Urrútia, G., & Bonfill, X. (2010). Declaración PRISMA: una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Medicina Clínica, 135(11), 507-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2010.01.015

Valiente, Ó. (2008). ¿A qué juega la concertada? La segregación escolar del alumnado inmigrante en Cataluña (2001-06). Profesorado. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(2), 142-164.

Verger, A., Zancajo, A., & Fontdevila, C. (2016). La economía política de la privatización educativa: políticas, tendencias y trayectorias desde una perspectiva comparada. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 70, 47-78. https://doi.org/10.17227/01203916.70rce47.78

Vidal, C. (2017). El diseño constitucional de los derechos educativos ante los retos presentes y futuros. Revista de derecho político, 100, 739-766. https://doi.org/10.5944/rdp.100.2017.20716

Vilanou, C. (1982). Hace cien años: un debate parlamentario en torno a la libertad de enseñanza. Historia de la educación: Revista Interuniversitaria, 1, 9-22.

Villacañas, J. L. (2020). Neoliberalismo como teología política. Ned ediciones.

Villamor, P. (2007). La Libertad de Elección en el Sistema Educativo: el caso de España. Encuentros Sobre Educación, 8, 173-199. https://doi.org/10.24908/eoe-ese-rse.v8i0.589

Vintanel, B. (2017). Análisis de los debates parlamentarios de las leyes orgánicas de educación promulgadas en España desde 1980 a 2013. (Tesis doctoral. Universidad Zaragoza).

Viñao, A. (2020). Educación, jueces y constitución 1978-2018. La educación separada por sexos. Historia y Memoria de la Educación, 11, 435–473. https://doi.org/10.5944/hme.11.2020.25514

Contact address: Enrique-Javier Díez-Gutiérrez. Universidad de León, Facultad de Educación, Departamento de Didáctica General, Específicas y Teoría de la Educación. Campus de Vegazana s/n. 24071 Universidad de León. España. E-mail: ejdieg@unileon.es

1 National investigation PID2019-105631GA-I00 “The influence of neoliberalism on academic identities and in the level of professional satisfaction” and European Project 620320-EPP-1-2020-1-ES-EPPJMO-MODULE “Building up an Inclusive and Democratic Europe through a Dialogical Co-Creation of Intercultural Solutions to the Rise of Neo-Fascism and Xenofobia”.

2 Scielo was also searched, but no significant references were found, so it was excluded from the analysis.