Collaboration between family and school and its

relationship with the social and academic skills of Roma

students from the Canary Islands

Colaboración entre familia y escuela y su relación con

las competencias sociales y académicas del alumnado de

etnia gitana de Canarias

DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2021-394-512

José Carmona-Santiago

Marta García-Ruiz

Mª Luisa Máiquez

Maria José Rodrigo

Universidad de La Laguna

Abstract

The social gap of the Roma people is still substantial, and extends to the school dimension in the form of greater school dropout and failure rates. The present study has a twofold objective: a) to analyze the perception, on the part of both parents and teachers, of the quality of relationships between family and school; and b) to examine the extent to which the quality of said collaboration is related to the children’s social skills and academic competence. The participants were 60 families of Roma ethnicity, 80 children of these families, and 33 teachers who teach them, residing in the Canary Islands. The data were collected by means of questionnaires and analyzed using descriptive analyses and the CHAID decision tree technique. The independent variables were the factors of the family-school collaboration questionnaire, the variables of the families’ socio-demographic profile, the existence of inappropriate behaviors at school, and school absenteeism. The dependent variable was the factors of the students’ social skills and academic competence. The results showed that families and teachers perceived a good atmosphere at school but a low level of participation in school activities. The level of social skills in the students was good, and the decision trees indicated that this was associated with an absence of inappropriate behaviors at school, more family support with schoolwork, and more family participation in school activities. Academic competence was lower and associated with less family support with schoolwork and more absences from class. In conclusion, in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands, the educational inclusion of the Roma people is possible, and with additional efforts to improve family-school collaboration, it will also be possible to improve educational success.

Keywords: Roma people, family-school collaboration, social skills, academic competence, school integration.

Resumen

La brecha social del Pueblo Gitano sigue siendo notoria y se proyecta en la dimensión escolar en cuanto al mayor abandono y fracaso escolar del alumnado. El presente estudio tiene un doble objetivo: a) analizar la percepción, tanto de los padres y las madres como del profesorado, sobre la calidad de las relaciones entre la familia y la escuela; y b) examinar en qué medida la calidad de dicha colaboración se relaciona con las competencias sociales y académicas de los hijos e hijas. Los participantes eran 60 familias de etnia gitana, 80 hijos/as de estas familias y 33 profesores/as que les impartían docencia, residentes en las Islas Canarias. La información fue recogida a través de cuestionarios y los datos se analizaron mediante análisis descriptivos y la técnica de árboles de decisión CHAID. Las variables independientes fueron los factores del cuestionario de colaboración familia-escuela, las variables del perfil sociodemográfico de la familia, la existencia de conductas inapropiadas en el centro educativo y el absentismo escolar. La variable dependiente fueron los factores de competencias sociales y académicas en el alumnado. Los resultados muestran que las familias y los profesores percibían un buen clima en el centro escolar, siendo baja la participación familia-escuela. El nivel de competencias sociales en el alumnado era bueno y los árboles de decisión señalaron que estaba asociado a tener menos comportamientos inadecuados en la escuela y a un mayor nivel de apoyo familiar en las tareas escolares y de colaboración de la familia con la escuela. Las competencias académicas eran más bajas y estaban asociadas a un menor apoyo de las familias en las tareas escolares y con las faltas a clase. En conclusión, en la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias la inclusión educativa del Pueblo Gitano está siendo posible y con esfuerzos adicionales para mejorar la colaboración familia-escuela será posible también mejorar el éxito educativo.

Palabras clave: Pueblo gitano, colaboración familia-escuela, competencias sociales, competencias académicas, integración escolar.

Introduction

The oldest and largest ethnic minority in Europe is that of the Roma or Gypsy people. It is estimated that there are over 12 million Roma in Europe, with their presence on the Iberian peninsula dating back to the fifteenth century and the population in this part of the continent currently numbering approximately 700 000 (Hancock, 2011; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2012). As the Federación de Asociaciones Gitanas de Cataluña (2017) has indicated, the social gap between the Roma people and the majority population continues to be substantial, even though Spain is considered across Europe to be a model in terms of integration of this ethnic group. According to the VII Informe sobre Exclusión y Desarrollo Social en España en 2014 (VII Report on Social Exclusion and Development in Spain from 2014), 54.4% of the country’s Roma population live in severe exclusion, as compared to 9.5% of the non-Roma population (FOESSA, 2014). As stated by Parra et al. (2017), the social segregation suffered by the Roma people extends to the school dimension. According to the Fundación Secretariado Gitano (2019), only 15.45% of Roma women and 19.4% of Roma men successfully complete compulsory secondary education, with the corresponding figures in the general population being 75.2% for women and 78.3% for men. Only 2.8% of Roma women and 4.6% of Roma men have an education beyond this level, while in the general population 52% of women and 50.8% of men do. As we can see, this represents not only a social gap but also a gender gap, with Roma women suffering double discrimination.

The consensus in the literature is that the social inequalities and marginalization of the Roma are the result of the values, ideologies, and policies practiced over centuries (Gómez-Alfaro, 2010), resulting, as Salinas (2015) says, in “seis siglos de conciudadanía accidentada” (“six centuries of checkered coexistence”, p. 96). Considering this in the school context, it has already been recognized in Europe that the situation of Roma students is the result of outdated educational policies leading to extreme positions such as forced assimilation or de facto segregation (Council of Europe, 2008). In the same vein, research conducted in different countries by Giménez-Adelantado et al. (2002) has shown clear educational disadvantages for ethnic Roma schoolchildren, with political, socioeconomic, cultural, and ideological factors underpinning the relations between Roma students and their schools.

In addition to considering the negative impact of macro-systemic factors on Roma students’ ability to access education, one must also take into account the functioning of the family micro-system and the nature of its relationship with the school micro-system. This mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1987), made up of the fabric of family-school relationships, has received less attention in studies of ethnic Roma students (Carmona-Santiago et al., 2019). The quality of these relationships can have a major influence on classroom dynamics and educational success (Epstein, 2011; García-Bacete & Martínez-González, 2006). As indicated by Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., (2016), collaboration between schools, families, and the community is key, as is the need to establish relationships in which all parties support each other and try to harmonize their contributions to improve students’ learning, motivation, and school performance.

The adoption in Spain of the Estrategia Nacional para la Inclusión Social de la Población Gitana 2012-2020 (National Strategy for Social Inclusion of the Roma People 2012-2020, Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2012) has injected fresh energy into the policies and measures promoting the social inclusion of the Roma people in this country. Under this strategy, 96% of Roma children have now been enrolled in compulsory education and 87% of children of preschool age are in early education. However, absenteeism is still high (14.3%) and dropout rates, especially among girls, remain a concern (74% of dropouts leave school before completing compulsory secondary education, with some girls even leaving the school system upon completing compulsory primary education). Improving academic results remains a major challenge, as only 22.2% of Roma students successfully complete compulsory secondary education. Further progress will only be possible with increased awareness among families and more support for families to become involved in school life, knowing that key factors in this process are parents’ future expectations linked to their children’s academic success, parents supporting children in adapting to school routines and demands, support and sustained commitment on the part of teachers, and a positive atmosphere of involvement in the school (Parra et al., 2017; Rubio, 2014).

The present study focuses on the binomial of family-school relationships and how these are linked to social skills and academic competence in ethnic Roma students in the Canary Islands. The case of the Roma population resident in the Canary Islands is a particularly good example to use, as the Roma are not generally a socially marginalized population in the Islands, thus allowing us to analyze the mesosystemic conditioning factors of educational success not connected to the social exclusion generally suffered by this group in other parts of Spain. Specifically, the study has two aims. The first is to examine parents’ and teachers’ perceptions of family-school collaboration. The second is to analyze the degree to which the quality of family-school relationships is linked to the children’s social skills and academic competence, taking into account socio-demographic profiles, school absenteeism, and the existence of inappropriate behaviors at school. Most studies dwell on academic competence, for which we predict low performance in our sample linked with greater school absenteeism. Thus, Parra et al. (2017) indicate that Roma students lag behind in key areas like reading, writing, mathematics, and social studies starting in primary education, often leading them to repeat years and placing them in a difficult position when it comes to facing the challenges of secondary education. Less is known, however, about their social skills, meaning that we do not have clear prior findings on which to base our hypotheses. Generally, studies have shown that students’ social and emotional skills are a key factor in educational success (Losada, 2015). Thus, being assertive, communicative, cooperative, empathetic, accepted by one’s peers, and adapted to the demands of school are all related to academic success. In sum, the results of the present study will help shed light on the quality of family-school collaboration and how it relates to a more complete, differentiated image of educational success, by considering both social skills and academic competence in students of Roma ethnicity.

Method

The present research is framed as a non-experimental, ex post facto, descriptive study with non-probability intentional sampling.

Sample

Given the lack of official statistics, the authors worked with pastors and representatives of a Roma evangelical association to draw up a list of Roma families with children from 6 to 17 years of age residing in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands (approximately 100 in total). Participants were 60 Roma families (18 fathers and 42 mothers) with children aged from 6 to 17 (38 female and 42 male), as well as 33 teachers who teach these children.

Table I shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the families interviewed. The participating fathers and mothers had an average age of 38 years old. The educational level of the fathers and mothers were mostly from primary studies (63.3%), followed by 10% graduated from ESO. Regarding the employment situation of the fathers and mothers, 38.3% were unemployed, 35% were self-employed, and 6.7% worked for a company.

TABLE I. Fathers’ and mothers’ socio-demographic variables

|

Father and Mother |

||

|

N |

M (SD) o % |

|

|

Age |

60 |

38,38 (4,10) |

|

Educational level |

||

|

No formal education |

14 |

23,3 |

|

Primary education |

38 |

63,3 |

|

Completed compulsory secondary education |

6 |

10,0 |

|

Vocational training |

2 |

3,3 |

|

Advanced high school diploma |

0 |

0,0 |

|

University studies |

0 |

0,0 |

|

Employment |

||

|

Unemployed |

23 |

38,3 |

|

Unemployed but with some casual work |

4 |

6,7 |

|

Self-employed |

21 |

35,0 |

|

Employed at a company |

4 |

6,7 |

|

Retired |

8 |

13,3 |

Source: compiled by authors

Turning now to the students (see Table II), 52.5% were boys and 47.5% were girls, with an average age of about 11. Of the total, 43.8% were in primary education, most (70%) in a public school. It is worth noting that only 15% of the students had been formally reported at school for inappropriate behavior. A total of 43.7% had unexcused absences from school.

TABLE II. Students’ socio-demographic variables and behavior at school

|

N |

M (SD) % |

|

|

Age |

11.51 (2.85) |

|

|

Sex Male Female |

42 38 |

52.5 47.5 |

|

Educational level Primary Secondary |

35 45 |

43.8 56.2 |

|

Type of school Public Charter |

56 24 |

70.0 30.0 |

|

Inappropriate behavior at school No Yes |

68 12 |

85.0 15.0 |

|

School absenteeism No Yes |

45 35 |

56.3 43.7 |

Source: compiled by authors

Of the teachers, 38.9% were male and 61.1% were female. In terms of teaching experience, 36.1% had 1 to 5 years, 31.3% had 6 to 15 years, and 23.8% had more than 15 years of experience. Also, 77.0% of the teachers had been working at the school in question for 5 years or less, 16.4% for 6 to 15 years, and 6.8% for more than 15 years.

Instruments

– Socio-demographic profile of families, students, and teachers, and measure of school behavior. For the present study, an abridged version of the Cuestionario de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud a Población Gitana 2013-2014 (Questionnaire for the Roma National Health Survey 2013-2014, Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, 2016) was used to collect the family data. For the parents, we recorded age, educational level, and employment status. For the students, we collected data on age, sex, current educational level, type of school, the existence of inappropriate behavior at school, and absenteeism. For the teachers, the data collected was sex, years of teaching experience, and years worked at the current school.

– Questionnaire on study conditions and family-school relations, parents’ and teachers’ versions (Martínez-González, 1996). The version for families has 58 items and 4 factors: Factor 1 Family’s difficulties in participating in school activities (5 items, α = .94), with the following points: 1) the family’s personal and work-related difficulties in participating in school activities, 2) the family’s interest in participating, and 3) the school’s requests that the family participate in school activities; Factor 2 Educational supervision and contact with teachers to deal with problems (13 items, α = .92), which analyzes: 1) supervision of children by fathers and mothers, and 2) contact with teachers to discuss positive or negative aspects related to their children; Factor 3 Academic performance and schoolwork (17 items, α = .98), which examines: 1) the children’s effort to achieve good grades, 2) the difficulties they have completing schoolwork, and 3) the support the family receives from teachers with regard to schoolwork; Factor 4 School atmosphere and opinion of teachers (10 items, α = .93), which analyzes: 1) the relationship with other families at the school, 2) the existence of discrimination against the family and their children, 3) the skill with which teachers do their work, and 4) the teachers’ involvement in the education and socialization of the family’s children. The version for teachers has 54 items and 3 factors: Factor 1 Family collaboration with the school: contacts and difficulties (10 items, α = .88), which looks at: 1) relationships, meetings, and direct contacts between teachers and the family to address the students’ academic progress, 2) the family’s interest in participating in school activities, and 3) the family’s participation in the parent-teacher association; Factor 2 Study atmosphere at home / students’ schoolwork and activities (12 items, α = .93), which examines family activities related to: 1) supervision, support, and help with children’s schoolwork, 2) adapting the home environment, and 3) conflicts between father and mother due to the children’s academic activities; Factor 3 Parents’ support for teachers (14 items, α = .90), which analyzes: 1) how the family feels in the school, 2) the support the teachers receive from the family when they have problems with the students, 3) justifications provided when the children’s behavior is not in line with the rules, and 4) the encouragement provided to teachers for the work they do. In both version, the responses are recorded using a Likert-type scale and measure both frequency (0-2 never; 3-5 sometimes; 6-8 often; 9-11 always) and degree of agreement (0-2 completely disagree; 3-5 disagree; 6-8 agree; 9-11 completely agree).

– Social Skills Improvement System-Rating Scales (SSIS-RS) (Gresham & Elliot, 2008; Spanish version by Hidalgo & Jiménez (2005)). The SSIS-RS offers information on student competence along three dimensions: 1) Social skills: Likert-type scale with three possible responses (1 = never, 2 = often, and 3 = almost always), with higher scores related to higher self-control, assertion, and cooperation, with Cronbach’s α = .91; 2) Problem behaviors: Likert-type scale with three possible responses (1 = never, 2 = often, and 3 = almost always), related to problems with internalizing, externalizing, and hyperactivity, with Cronbach’s α = .82; and 3) Academic competence: Likert-type scale with 9 items and 5 possible responses (1 = very low, among the bottom 10% of the class to 5 = very high, among the top 10% of the class), describing the student’s academic performance in relation to the class average, with Cronbach’s α = .91. Informants were the teachers who had indicated that the children were their students.

Procedure

Once the potential participating families had been identified from the list provided by the pastors and representatives of the Roma association, the fathers and/or mothers were contacted and offered the opportunity to participate in the study. A total of 95 families signed the informed consent in accordance with the requirements of the Ethics Committee of the University of La Laguna. Then, 35 schools on the islands were contacted, of which 24 agreed to participate, meaning that student information was lacking for 35 of the Roma families, reducing the sample size considerably. In the end, study participants were 60 Roma families (18 fathers and 42 mothers) with children aged from 6 to 17 (38 female and 42 male), as well as 33 teachers who teach these children.

Design and Analysis

This was a quantitative exploratory study with the following independent variables: the family’s socio-demographics, the family-school relationship (the four factors from the questionnaire for fathers and mothers and the three factors from the version for teachers), the students’ socio-demographics, inappropriate behavior at school, school absenteeism, and teachers’ socio-demographics. Dependent variables were the three dimensions from the rating scales: students’ social skills, problem behavior, and academic competence.

For the first aim, descriptive analyses were run for the factors from the family-school relations questionnaire (with families and teachers as informants) and for the student competence factors (with teachers as informants). For the second aim, examining the relationship between independent and dependent variables, the decision tree (Berlanga et al., 2013) data mining technique was used, with a CHAID classification analysis. The decision tree models the most robust interaction of the independent variables affecting each of the dependent variables and the iteration algorithms on each branch that splits off (Linoff & Berry, 2011). The CHAID technique analyzes all scores for each potential predictor variable using the chi-squared method, which reflects the degree of association between the variables, then selects the most significant predictor to create the first split on the decision tree, and continues with the following predictors until the tree is complete. The CHAID technique uses very robust mathematical algorithms that do not require linear relation conditions from parametric tests which, as in the present study, are often difficult to meet. All the analyses were run using the statistical package SPSS version 24.0.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Table III shows the results for the factors of the perception of family-school relations questionnaire with fathers and mothers as informants. The analyses showed lower scores in the measure of the family’s difficulties in participating in school activities (Factor 1, M = 4.07; SD = 1.97). The families reported higher scores for school atmosphere and opinion of teachers (Factor 4, M = 7.72; SD = 1.85).

TABLE III. Perception of family-school relations, with fathers and mothers as informants (scale from 1 to 11)

|

M (SD) |

||

|

Factor 1: |

Family’s difficulties in participating in school activities |

4.07 (1.97) |

|

Factor 2: |

Educational supervision and contact with teachers to deal with problems |

6.81 (1.55) |

|

Factor 3: |

Academic performance and schoolwork |

5.83 (1.50) |

|

Factor 4: |

School atmosphere and opinion of teachers |

7.72 (1.85) |

Source: compiled by authors

Table IV shows the results for the factors of the perception of family-school relations questionnaire with teachers as informants. The results showed lower scores for family collaboration with the school, in particular with respect to difficulties contacting parents (Factor 1, M = 4.70; SD = 1.46). The highest scores were reported for parents’ support for teachers (Factor 4, M = 6.63; SD = 1.85).

TABLE IV. Perception of family-school relations, with teachers as informants (scale from 1 to 11)

|

M (SD) |

||

|

Factor 1: |

Family collaboration with the school: contacts and difficulties |

4.70 (1.46) |

|

Factor 2: |

Study atmosphere at home / students’ schoolwork and activities |

5.88 (1.51) |

|

Factor 3: |

Parents’ support for teachers |

6.63 (1.99) |

Source: compiled by authors

Table V shows the results for the factors from the Social Skills Improvement System – Rating Scales, which was completed by the teachers. The analyses show lower scores for problem behaviors (Factor 1, M = 1.36; SD = .32), with the highest scores seen for students’ academic competence (Factor 3, M = 2.76; SD = 1.02).

TABLE V. Results of the Social Skills Improvement System – Rating Scales

|

(Scale 1-3) |

M (SD) |

|

|

Factor 1: |

Social skills |

2.19 (.38) |

|

Factor 2: |

Problem behaviors |

1.36 (.32) |

|

(Scale 1-5) |

M (SD) |

|

|

Factor 3: |

Academic competence |

2.76 (1.02) |

Source: compiled by authors

b) Exploratory analysis using decision trees with CHAID for classification

Below are the decision trees with the student competence dimensions as dependent variables and the variables reported above in the analysis plan as independent variables. The results of the CHAID analysis for the dependent variable Social skills show associations with three predictor variables: Inappropriate behavior at school, Family support with schoolwork and School’s difficulties contacting the family, with six nodes generated, three of which are terminal (Figure I). The most significant variable explaining the students’ social skills is Inappropriate behavior at school. Thus, of those students who have been formally reported at school for inappropriate behavior, 12% (Node 1), the mean for social skills is very low (M = 1.73; SD = 0.30). However, of the students who have not been formally reported for inappropriate behavior, 88% (Node 2), the mean is higher (M = 2.27; SD = 0.33). Of this group, those who do not have Family support with schoolwork according to their teachers (Node 3) have a lower mean for social skills (M = 2.11; SD = 0.36) than those who do have this support (Node 4) from their family (M = 2.36; SD = 0.29). Finally, in those students who have more support from their family, there is greater Family collaboration with the school (teacher informants), with greater social skills (M = 2.40; SD = 0.23) than for those students whose families do not collaborate (M = 2.26; SD = 0.26).

FIGURE I. CHAID decision tree for the dependent variable of social skills

Source: compiled by authors

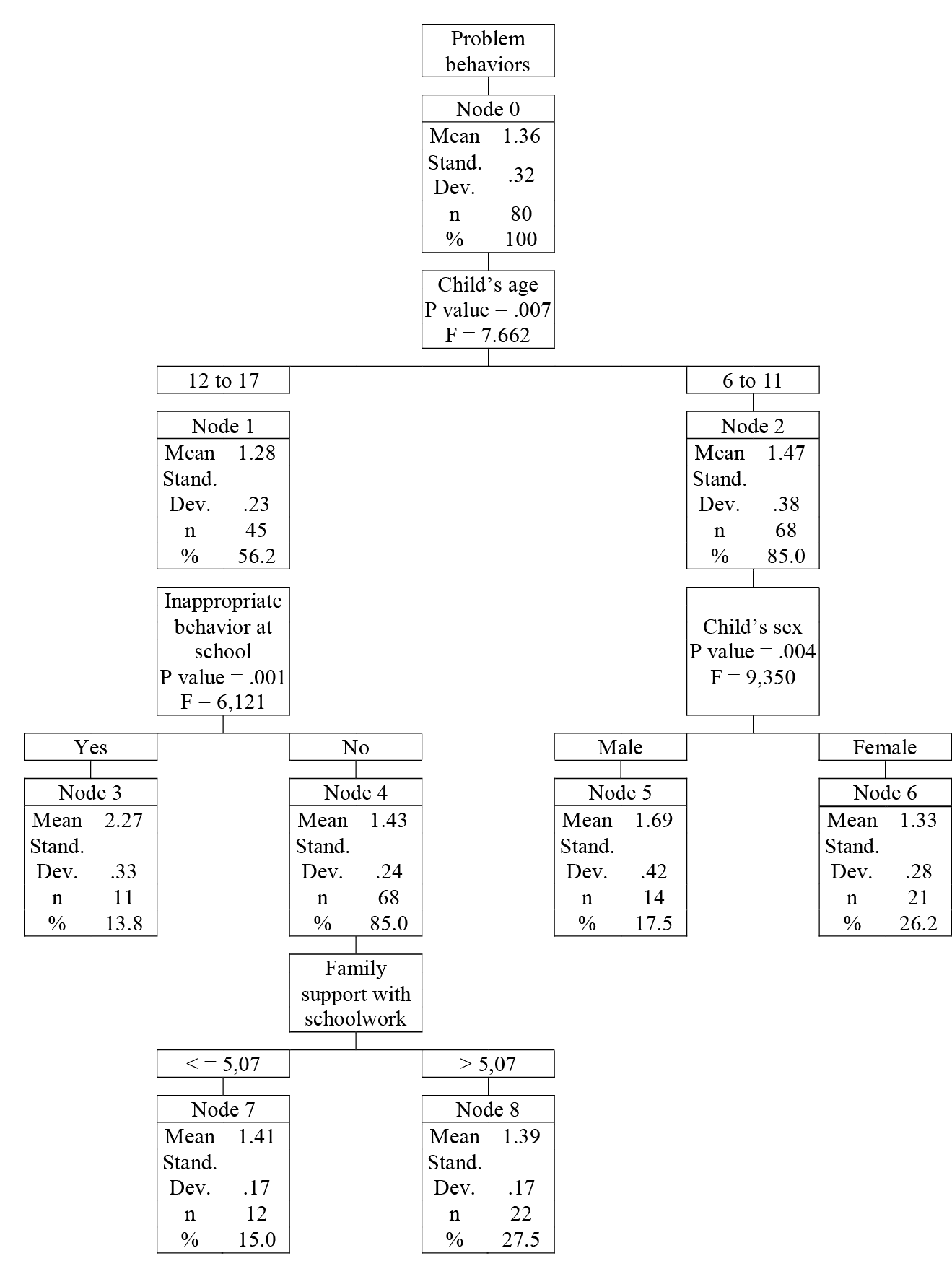

The results of the CHAID analysis for the dependent variable Problem behaviors show different associations, generating seven nodes, of which four are terminal (Figure II), with the most significant being Child’s age. In adolescence (Node 1), there are fewer personal problem behaviors (M = 1.28; SD = 0.38) than in childhood (Node 2) (M = 1.47; SD = 0.38). Adolescents who show Inappropriate behavior at school (Node 3) have more problem behaviors (M = 2.27; SD = 0.33) than those who do not (Node 4) (M = 1.43; SD = 0.23). Of the latter group, those who do not have Family support with schoolwork (teacher informants) (Node 7) have more problem behaviors that those who do (Node 8). The other association is with Child’s sex, with boys (Node 5) having higher mean problem behaviors (M = 1.69; SD = 0.42) than girls (M = 1.33; SD = 0.28).

FIGURE II. CHAID decision tree for the dependent variable of problem behaviors

Source: compiled by authors

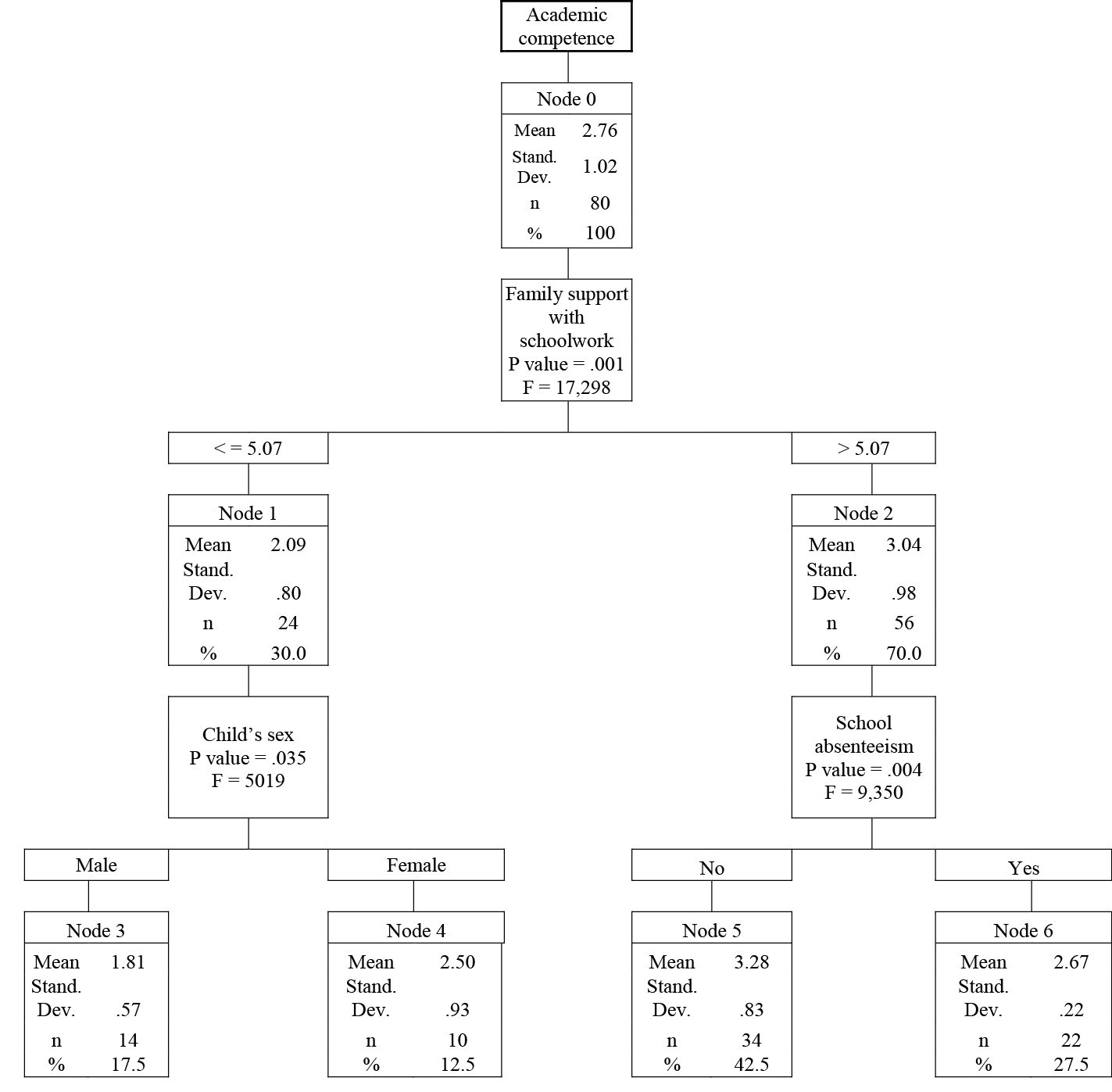

Finally, the CHAID analysis for Academic competence, which generated seven nodes, of which four are terminal (Figure III), reveals that the most influential variable is Family support with schoolwork (teacher informants). Students who do not have this support (Node 1) show lower academic competence (M = 2.09; SD = 0.80) than those who do have this support (Node 2), for whom competence is higher (M = 3.04; SD = 0.98).

FIGURE III. CHAID decision tree for the dependent variable of academic competence

Source: compiled by authors

Of those who do not have family support with schoolwork, boys (Node 3) have lower academic competence compared to their classmates (M = 1.81; SD = 0.57), while the mean for girls (Node 4) is higher, yet still low when compared to their classmates (M = 2.50; SD = 0.93). Of the students who have family support, those with low School absenteeism, 42.5% (Node 5), show academic competence in line with the mean for the student body (M = 3.29; SD = 0.83), while those who are often absent from school, 27.5% (Node 6), had lower academic competence that their classmates (M = 2.67; SD = 1.10).

Discussion and Conclusions

The first aim of the present study was to study perceptions of family-school collaboration on the part of fathers and mothers of Roma ethnicity and of their children’s teachers. On the negative side, the analyses showed lower scores related to families’ difficulties in participating in school activities. Similarly, from the teachers’ standpoint, there were lower scores given for family collaboration with the schools, in particular with respect to difficulties encountered in contacting parents. There is therefore considerable agreement between families and teachers that there is a lack of family participation in school life.

On the positive side, the families reported high scores for school atmosphere and opinion of teachers. These perceptions are corroborated by teachers, who give the highest scores for parents’ support for teachers. It is clear that for Roma families in the Canary Islands, most of whom participated in this study, decisive steps are being taken to ensure that their school-age children are integrated into the school system. Unlike what has been reported by Parra et al. (2017), Roma children in the Canary Islands do not seem to suffer segregation or exclusion at school, probably because they are from families who are also not socially marginalized. It also helps that schools in the Canary Islands take cultural diversity into account – as one of Europe’s outermost regions, the Islands constitute a major port of entry for migratory flows, leading to the coexistence of many different cultures in schools (Hernández, 2017).

The study’s second aim was to examine the role of family-school collaboration and its relation to children’s social skills and academic competence. As a novelty, the results show that the students’ social skills are reported by teachers to be medium to high. According to the decision trees, a lower degree of social skills is mainly related to inappropriate behavior at school (although only 15% of the sample demonstrated such behavior), followed by low levels of family support with schoolwork and family-school collaboration, which in turn is related to greater school absenteeism (which affects 47.3% of students). For the Roma people, centuries of survival in different environmental, economic, social, and cultural circumstances have led to the acquisition of a range of social skills that help ensure their subsistence (Gómez-Alfaro, 2010; Hancock, 2011; Magano & Mendes, 2021; Myers, 2018). It is also important to point out that the culture transmitted to Roma children by their families includes values that place the group before the individual, leading to greater development of values such as solidarity, empathy, cooperation, and loyalty, as well as opportunities to put them into practice (Range & Gratero, 2010).

On another positive note, Roma students in the Canary Islands show low levels of problem behaviors, which is a reflection of good mental health overall. Again, it is worth noting that these students do not suffer the educational or social exclusion and marginalization that tend to be risk factors for personal and social adjustment (Fundación Secretariado Gitano, 2019). According to the decision trees obtained, problem behaviors are related to inappropriate behavior at school, especially in older children and boys, and are also linked to low family support with schoolwork. Therefore, of all the aspects of family-school collaboration studied, it is family support with schoolwork that most acts as a protective element permitting a high level of social skills and a lower likelihood of suffering behavioral and social problems.

Turning now to academic competence, the present study showed, as expected, that Roma students in the Canary Islands have a lower level of competence than their classmates. These findings are similar to those of the study by the Fundación del Secretariado Gitano (2010), according to which “casi siete de cada diez niñas y niños gitanos se sitúan por debajo de la media de su grupo en cuanto al rendimiento escolar se refiere” (“almost seven out of ten Roma boys and girls perform below the average of their classmates in school”, p. 130). Using the CHAID hierarchical segmentation technique, however, we were able to elucidate the variables most influencing this, thus showing that poor academic performance is associated with less family support with schoolwork and with school absenteeism. It should be noted that in those students who do receive the family support they need to do their schoolwork and attend classes as normal, average academic performance is in line with that of their classmates. Similarly, low levels of family support for schoolwork have more of a negative effect on school performance in boys than in girls. As González (2006) states, repeated absences from school are accompanied by reduced academic competence in the learning process, which can translate into learning delays and even abandonment of the school system. School absenteeism is a dynamic, interactive, and heterogeneous process with a range of profiles and causes. There may be a mix of both student-related factors involving their personal, social, and family life and school-related factors involving course offerings, organization, and classroom atmosphere, among others (Gándara, 2008). The good news is that poor academic performance and absenteeism are not factors associated with an irreversible process: when family support is provided and attendance improves, the trend can be reversed. In this vein, Spain has already put into place a number of inclusion projects targeting the Roma community, which have already shown positive results. One example can be found in the Colegio Público de Educación Infantil y Primaria “Andalucía”, a public school located in the Polígono Sur –Tres Mil Viviendas estate in Seville, which also involves families and has led to a considerable reduction in school absenteeism, failure, and dropout rates among students. Similarly, according to the findings of the longitudinal project INCLUD-ED at the CEIP La Paz public school in Albacete, with the inclusion of Roma families in the school system, together with spaces for dialogue that facilitate community learning, academic performance among young Roma children has improved (Flecha & Soler, 2013).

Given the very relevant role of family support, it is essential to give impetus to the Positive Parenting model currently prevailing in Europe (Council of Europe, Recommendation Rec. 19, 2006) to foster the parenting skills in Roma families that will ensure their children’s comprehensive development. These skills foster the creation of healthy affective bonds; provide a structured setting for child-raising based on routines and habits; facilitate stimulation, support, and opportunities for learning; help parents recognize their children’s achievements and capacities; and support families in everyday life (Rodrigo et al., 2015). In this sense, it is essential that families and schools establish relationships in which all involved parties mutually support each other and try to harmonize contributions by creating good communication channels between parent figures and teachers, all with a view to improving students’ learning, motivation, academic competence, and personal and social skills (Álvarez-Blanco & Martínez-González, 2016; Criado & Bueno, 2017; Dumitrascu, 2020).

To strengthen the relationship between schools and Roma families, the school system must also undergo a profound transformation. As indicated by Lorenzo-Moledo, Míguez-Salina, and Cernadas-Ríos (2020), “la escuela sigue siendo una institución de la cultura hegemónica, que tiende a excluir e invisibilizar la identidad cultural de los grupos minoritarios” (“schools continue to be institutions of the hegemonic culture that tend to exclude and hide the cultural identity of minority groups”, p. 195). As Jiménez-González (2018) states, the history of the Roma people goes back millennia, and its transmission to the rest of the community is essential for overcoming prejudice, fostering intercultural coexistence, decolonizing history, and preventing mistakes. Also, the school micro-system must move toward collaborative class dynamics based on respect, tolerance, and equality in an atmosphere of equal communication and mutual respect between students and teachers (Hernández-López et at., 2015).

There are some limitations to the present study. The study has taken a descriptive approach, and the sample size does not allow for generalizations or predictions based on the results obtained. This is due to the fact that the Roma community in the Canary Islands is small and that no such prior studies had been conducted here. It will be necessary to include other family and school variables to cover a broader range of possibilities associated with student skills and competence. However, as the first such study focusing on family-school collaboration in the Roma community in the Canary Islands, the present study will undoubtedly act as a catalyst for future research.

In sum, the present study, using a descriptive approach, has shown how educational inclusion of Roma students is possible in the Canary Islands. The example of this community, with all its good points and drawbacks, illustrates how good collaboration between families and schools can be achieved when stigma are overcome, and shows that students can reach similar levels of social skills and mental health outcomes. We have also demonstrated how additional family-school collaboration efforts to foster support for schoolwork and regular school attendance can bring the academic performance of Roma students into line with that of their non-Roma classmates. Without a doubt, the study of Roma families in the Canary Islands has opened up new vistas of a promising future for children and families of Roma ethnicity and, by extension, for all of society.

References

Álvarez-Blanco, L., y Martínez-González, R. (2016). Cooperación entre las familias y los centros escolares como medida preventiva del fracaso y del riesgo de abandono escolar en adolescentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 10(1), 175–192.

Berlanga, V., Rubio, M. J., y Vilà, R. (2013). Cómo aplicar árboles de decisión en SPSS. Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 6(1), 65- 79. DOI:10.1344/reire2013.6.1615

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1987). La ecología del desarrollo humano. Barcelona: Paidos.

Carmona-Santiago, J., García, M., Máiquez, M. L., y Rodrigo, M.J. (2019). El impacto de las relaciones entre la familia y la escuela en la inclusión educativa de alumnos de etnia gitana. Una revisión sistemática. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 9(3), 319–348. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.17583/remie.2019.4666

Consejo de Europa. Rec (2008) Recomendación sobre las políticas relativas a los Romas y/o a las Gentes del Viaje en Europa (adoptada por el Comité de Ministros el 20 de febrero de 2008). Recuperado de https://unionromani.org/notis/2008/noti2008-05-13.htm.

Criado, E., y Bueno, C. (2017). El mito de la dimisión parental. Implicación familiar, desigualdad social y éxito escolar. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 35(2), 35

Dumitrascu, T. (2020). Intellectual Development of Children in Gypsy Families in Romania. In: Walter J. Lonner, Dale L. Dinnel, Deborah K. Forgays, Susanna A. Hayes (eds), Merging Past, Present, and Future in Cross-cultural Psychology. London: Garland Science (ebook).

Epstein, J.L. (2011). School, Family and Community Partnerships. Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Philadelphia: WESTVIEW Press.

Flecha, R., & Soler, M. (2013). Turning difficulties into possibilities: Engaging Roma families and students in school through dialogic learning. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.819068

FOESSA., F. (2014). VII Informe sobre exclusión y desarrollo social en España 2014 (Vol. 11). Cáritas Española.

Fundación del Secretariado Gitano (2010). Discriminación y Comunidad Gitana. Informe Anual. Madrid: Fundación Secretariado Gitano. Recuperado de: https://www.gitanos.org/centro_documentacion/publicaciones/fichas/55992.html.es

Fundación Secretariado Gitano (2019). Estudio comparado sobre la situación de la población gitana en España en relación al empleo y la pobreza 2018. Madrid: Fundación Secretariado Gitano. Retrieved from https://www.gitanos.org/upload/14/89/Informe_de_discriminacion_2018__ingles_.pdf

Gándara, J. (2008). El “fracaso escolar” de los alumnos desenganchados de la escuela: una forma de exclusión social. En La Calle: Revista Sobre Situaciones de Riesgo Social, (9), 2–5.

García-Bacete, F. y Martínez-González, R. (2006). La relación entre los centros escolares, las familias y los entornos comunitarios como factor de calidad de la educación de menores y adultos. Cultura y Educación, 18(3-4), 213-218.

Giménez-Adelantado, A., Piasere, L., & Liegeois, J. P. (2002). The education of Gypsy childhood in Europe. Final report. Opre Roma, (30 May), 1–98. Recuperado de http://cordis.europa.eu/documents/documentlibrary/82608111EN6.pdf

Gómez-Alfaro, A. (2010). Escritos sobre gitanos. Valencia: Asociación de Enseñantes con Gitanos.

González, M. (2006). Absentismo y abandono escolar: Una situación singular de la exclusión educativa. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 4(1), 1-15.

Gresham, F., & Elliott, S. (2008). Social skills improvement system (SSIS) rating scales. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022662

Hancock, I. (2011). The neglected memory of the romanies in the Holocaust/Porrajmos. In Friedman (Ed.), The Routledge history of the holocaust (pp. 375-384) Routledge. London

Hernández, L. (2016). Análisis de la competencia cultural y artística en educación física a través de las prácticas motrices tradicionales canarias: Un estudio de casos en educación secundaria obligatoria. Acciónmotriz, (17), 37–46.

Hernández-López, C., Jiménez-Álvarez, T., Araiza-Delgado, I., y Vega-Cueto, M. (2015). La escuela como una comunidad de aprendizaje. Ra Ximhai, 11(4), 15–30.

Hidalgo, M. y Jiménez, L. (2005). Traducción y adaptación al español del cuestionario Social Skills Rating System. Versión de profesores. Manuscrito no publicado, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla.

Jiménez-González, N. (2018). La historia del pueblo gitano: memoria e inclusión en el curriculum educativo. Drets. Revista Valenciana de Reformes Democràtiques, (2).

Linoff, G. y Berry, M. (2011). Data mining techniques: for marketing, sales, and customer relationship management. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lorenzo-Moledo M, Míguez-Salina G, y Cernadas-Ríos F. (2020). ¿Pueden contribuir los fondos de conocimiento a la participación de las familias gitanas en la escuela? Bases para un proyecto educativo. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria [Internet].32, 191-211.Disponible en: https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/1130-3743/article/view/21299

Losada, L. (2015). Adaptación del “social skills improvement system-rating scales” al contexto español en las etapas de educación infantil y educación primaria (Tesis doctoral). Facultad de Educación. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Retrieved from http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view/tesisuned:Educacion-Mllosada

Magano O., Mendes M.M. (2021) Key Factors to Educational Continuity and Success of Ciganos in Portugal. In: Mendes M.M., Magano O., Toma S. (eds). Social and Economic Vulnerability of Roma People. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52588-0_9

Martínez-González, R. (1996). Familia y educación. Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad (2012). Estrategia Nacional para la Inclusión Social de la Población Gitana en España 2012-2020. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Recuperado de: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/ssi/familiasInfancia/PoblacionGitana/docs/WEB_POBLACION_GITANA_2012.pdf

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e igualdad. (2016). Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Salud a Población Gitana, 2014. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad.

Myers, M. (2018). Gypsy students in the UK: the impact of ‘mobility’ on education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(3), 353-369. doi:10.1080/13613324.2017.1395323

Parra, I., Álvarez-Roldán, A., y Gamella, J. F., (2017). Un conflicto silenciado: Procesos de segregación, retraso curricular y abandono escolar de los adolescentes gitanos. Revista de Paz y Conflictos, 10(1), 35–60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.37.1.326221

Range, J., y Gratero, C. (2010). Habilidades sociales para el fortalecimiento del trabajo en equipo en las organizaciones educativas. INGENIERÍAUVM, 4(2), 216–228.

Rodrigo, M. J., Máiquez, M. L., Martín, J. C., Byrne, S., y Ruiz, B. R. (2015). Manual práctico de parentalidad positiva. Madrid: Síntesis.

Rodríguez-Ruiz, B., Martínez-González, R., y Rodrigo, M.J. (2016). Dificultades de las familias para participar en los centros escolares. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 10(1), 79–98.

Rubio, R. (2014). Análisis de las continuidades y discontinuidades entre escuela y familia gitana (Tesis doctoral). Facultad de Psicología. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Salinas, J. (2015). Una aproximación a la historia de la escolarización de las gitanas y gitanos españoles (2a Parte: Siglos XX y XXI). Cabás.

Contact address: José Carmona-Santiago. Universidad de La Laguna, Facultad de Psicología. Campus de Guajara C.P. 3807. E-mail: alu0100708653@ull.edu.es