Diachronic Analysis of Verbal Aggressiveness,

Machiavellianism and Bullying through Social Network

Analysis1

Análisis diacrónico de agresividad verbal, maquiavelismo

y bullying medianteanálisis de redes sociales

DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2021-394-504

Kyriaki Spanou

Alexandra Bekiari

Nikolaos Hasanagas

Universidad de Tesalia

Abstract

Aim of this research is the diachronic analysis of verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism among physical education students regarding their diachronic evolvement and stability of victimizers and victims during the semester. Standardized network questionnaires were used. Twelve network samples (students’ semester classes) were collected from four Greek departments (totally 538). Network variables (in/out-degree, Katz status, pagerank, authority) were calculated via Visone software while Spearman test was implemented for diachronic network analysis. Results: The strengthening of practicing such behaviours may reasonably be attributed to the fact that students become more and more familiar to each other during the semester. Threat appears to be stable and unchangeable in contrast to irony. Most stable bullying behaviour is “refusing help”. Evolvement of “exclusion” into “refusing help” was observed. “Deception” indicates a predisposition for “back-stabbing”. A remarkably weak stability of victimization in verbal aggressiveness was observed with “exclusion” to be a presage of further abuse.

Keywords: bullying; diachronic and network analysis; education; Machiavellianism; verbal aggressiveness

Resumen

El objetivo de esta investigación es el análisis diacrónico de la agresividad verbal, el bullying (acoso escolar) y el maquiavelismo entre los estudiantes de Educación Física en cuanto a su evolución diacrónica y la estabilidad de los agresores y las víctimas durante el semestre. Para ello se utilizaron cuestionarios de red estandarizados. Se recogieron doce muestras de redes (clases semestrales de estudiantes) de cuatro departamentos griegos (en total 538). Las variables de las redes (in/out-degree, Katz status, pagerank, authority) se calcularon mediante el software Visone, mientras que para el análisis diacrónico de las redes se aplicó la prueba de Spearman. Resultados: el fortalecimiento de la práctica de estos comportamientos puede atribuirse al hecho de que los estudiantes se familiarizan más entre sídurante el semestre. La amenaza parece ser estable e inalterable en contraste con la ironía. La conducta más habitual cuando se produce un acoso es la de “rechazar ayuda”. Se observó la evolución de la “exclusión” a la “denegación de ayuda”. El “engaño” indica una predisposición a la “puñalada por la espalda”. Se observó una estabilidad notablemente débil de la victimización en la agresividad verbal con “exclusión” comopresagio de la continuación del abuso.

Palabras clave: bullying; análisis diacrónico de redes, educación, Maquiavelismo; agresividad verbal

Introduction

Verbal Aggressiveness

Verbal aggression is used as a means of expressing feelings of rage implying destructive communication (Bekiari, 2012; Bekiari, Kokaridas & Sakellariou 2005; 2006; Bekiari, Perkos & Gerodimos, 2015; Syrmpas & Bekiari, 2018) expressed in various modes such as mockery, threats, irony etc (Myers, Brann & Martin, 2013). As for irony utterances, Burgers et al. (2016) proved that they can sometimes include communicative benefits focusing on the circumstances and thus, they alleviate anger without creating negative feelings on the receiver (Staunton et al., 2020). High levels of “externalized” aggression (incl. verbal aggression), namely reactive or spontaneous aggression (Otte et al., 2019) accompanied with high stress levels among college students, is associated with low grades, seeking to balance social status and academic performance (Al-Ali, Singh & Smekal, 2011). Consequently, the investigation of verbal aggression is of academic and practical relevance expected to explain sources and patterns of verbally aggressive behaviour in the university context preventing its future implications (Webb, Dula & Brewer, 2012).

Verbal aggressiveness is conceived as a whole of relations system: e.g. A is offended by B and C, C is offended by D, E and F etc. Thereby, all these relations of offenses within a community (a university students’ community) shape a hierarchized system (where student A is the most offended). This hierarchy can be analyzed by social network theory, expected to reveal such informal hierarchies and enable their examination as measurable structure (Bekiari & Hasanagas, 2016).

It is evident that verbal aggressiveness as an omnipresent anti-social behaviour at higher education constitutes a form of social interactions with various types of relations leading to hierarchies (e.g. the highest receiver of verbal aggressiveness or the lowest one) and therefore, it is advisable to be extensively investigated through the social network analysis where visualization, quantification and detection of relations created by this “venomous” behaviour can shed light on its roots, dormant intentions and impacts for decisive intervention programs to be implemented in the field of higher education (Bekiari & Hasanagas, 2015; Bekiari et al., 2015) such as the department of Physical Education and Sport Science due to the competitive nature of sports in order to eliminate it. This competitive nature of the Physical Education and Sport subject is of physical character (not only social character). Thus, it presents more occasions of direct aggression which may vary from slight or smart verbal challenges to even socially unacceptable verbal offenses during the sport exercising.

In this study, the social network analysis is going to be a diachronic (dynamic) one (cp. Theocharis & Bekiari, 2018). The opportunity of implementing dynamic analysis of a social network is not often provided, as it is time-consuming and the interviewees are not always willing to answer at least twice the same questionnaire. However, the dynamic analysis is important for detecting the evolvement and tendency of structures, which are not depicted through a non-dynamic (synchronic) analysis.

Bullying

Bullying has been defined as a subtype of violent behaviour constituting a repetition of undesirable actions consciously hurting or controlling a person characterized by inferiority and vulnerability in social, emotional or physical context (Allanson, Lester & Notar, 2015). Violence, argument, harassment and aggression are often described with the term bullying (Difazio et al., 2019).

Despite the numerous global surveys, there is a limited research on bullying cases at higher education (Young-Jones et al., 2015). The Department of Physical Education and Sport Science is particularly appropriate for bullying research due to the tangible competitiveness appearing in athletic contests. Such contests obviously contain direct challenges which vary from slightly provocative actions to even physical violence incidents (which, of course, rarely occur in other academic fields such as Philology or Physics). For this reason, in education (mostly in Physical Education), anti-bullying interventions are often more than necessary in order to alleviate or minimalize peer aggression efficiently (Andreou et al., 2020).

Bullying as a complicated pathogenic problem in contemporary society has to be analyzed not only at an individual but also at a peer-group level through the lens of social networking groups since it concerns a “group process” (Salmivalli, 2010). Therefore, it is highly recommended to clarify bullying via the approach of social network analysis among students at higher education, as there is a limited number of network-based studies up to now (Bekiari & Pachi, 2017).

Bullying relations, as all relations, shape hierarchies (more, less or least targeted vs. more, less or least victimizer) (Bekiari, Pachi & Hasanagas, 2017). Thus, social network analysis is appropriate for quantifying to what extent a student tends to be a victim or a victimizer within a student network (a semester class) (eg, Bekiari et al., 2019). A dynamic study of bullying relations network through the time (e.g., comparing the situation between the beginning and the end of the semester) constitutes an interesting research challenge.

Machiavellianism

Machiavellianism, according to Machiavelli’s thoughts, focuses on various immoral acts to retain power (Kotroyannos & Tzagkarakis, 2021). It has proved to encompass characteristics such as deceitfulness and other features of “unethical” behaviour throughout “competitive” relations in the name of individual profit (Zettler & Solga, 2013). As far as students’ inappropriate behavior at educational institutions is concerned, it has been demonstrated that Machiavellianism can signify a relevant behavior in future organizations, that is, the past performance signifies the future performance (Tang, Chen & Sutarso, 2008).

However, one is not just a victim of Machiavellianism or just a Machiavellian, but he may possess simultaneously both properties to different grades. Namely, the possible Machiavellian relations within a students’ class constitutes a network and these relations shape an hierarchy of Machiavellianism where each student may be more or less a victim of Machiavellianism and simultaneously more or less a Machiavellian. Once again, the Department of Physical Education and Sport Science is expected to be an appropriate research field, as the intensive athletic contests mentioned above, often create an eminently harsh way of competition, leading also to Machiavellian initiatives in order to achieve easy or certain victory.

Thus, such a consideration of Machiavellianism not at individual but at holistic level could provide a complete depiction of each position within the group, exploring the Machiavellian behaviour as a structural phenomenon. This approach has been achieved by complete network analysis (e.g., Bekiari & Spanou, 2018). Additionally, a diachronic analysis of the evolvement of Machiavellian hierarchies from the beginning to the end of the semester is also expected to provide interesting insights.

Research goal and Innovation

In this research, classes of students at university departments (physical education) have been diachronically analyzed as networks, wherein interactions were behaviours of verbal aggression, bullying and Machiavellianism. Specifically, this research is aiming at the diachronic analysis of these behaviours among students of all Physical Education departments of Greece (University of Athens, Thessaly, Thessaloniki and Thrace).

The theoretical added value lies in the fact that this analysis has been distinguished:

■ In exploration of evolvement of these behavioural phenomena diachronically (during a semester). The tendency to point out a main offender who practices them or a main victim (target) respectively is going to be detected.

■ In control of hierarchical stability between the beginning and the end of the semester. It was examined to what extent the main offender and the main victim tend to remain the same person from the beginning to the end of the semester. Through the examination of the diachronic stability of behaviours, behavioural core dimensions are expected to be differentiated from occasional/ accidental ones.

The practical added value lies in the recognition of core dimensions of negative behaviours which one should pay attention to in order to prevent or avoid them. Not all behavioural dimensions of these behaviours are equally persistent and characteristic. Their possible persistence or conversion into other forms of negative behaviour, are going to be examined.

Materials and Method

Network analysis is normally based on algebraic approach and not (only) on conventional statistics. Algebraic indicators are used for depicting hierarchies emerging from interactions (relations) among the nodes. The particular research analyzes networks of relations of verbal aggression, bullying and Machiavellian which are practiced and received among the nodes. The nodes are students belonging to a semester class, selected from various departments.

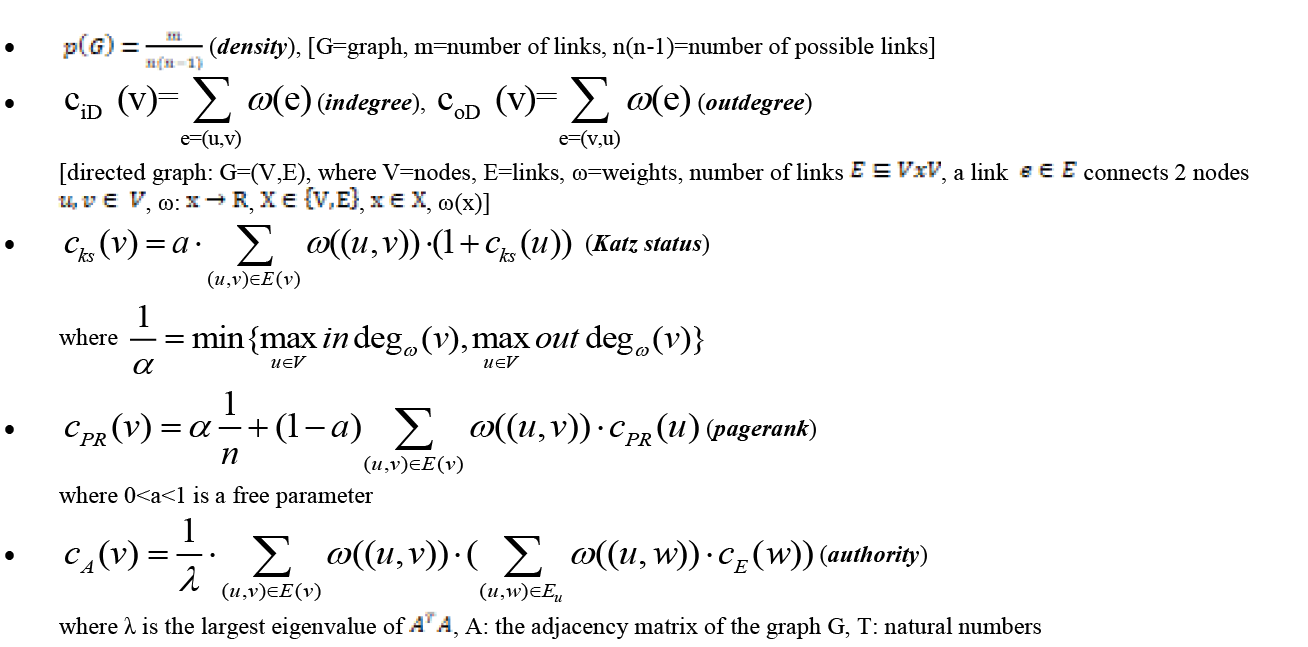

The indicators were calculated and normalized (%) by software Visone. (Although their formulas are accessible on the internet, they are also presented here)2 (Brandes & Wagner, 2004; Jünger & Mutzel, 2012). They were structurally interpreted as follows: 1) In-degree (and out-degree) depicts an occasional hierarchy (directly contacted nodes). 2) Katz Status expresses an accumulative hierarchy shaped by successive contacts. 3) Pagerank depicts a distributive hierarchy, expressing how the value is successively transferred (e.g., insulting) from each student to others. It is quite similar to Katz Status. Nevertheless, pagerank depicts more subtle layers of hierarchy and, thus, outliers are restricted. 4) Authority may be perceived as an indicator of a qualified competitiveness. Specifically, authority points out students attracting most links coming from as many other students as possible, who try to develop relations (practicing aggression, Machiavellianism or bullying).

Sample

The network sample is de facto not random. However, its non-randomness is not a weakness in this research, as the main goal is to provide not a descriptive statistic generalized on a total population but correlations (analytical statistics). Student networks were sampled from physical education departments because the Machiavellianism, verbal aggressiveness and bullying tend to develop intensively, due to the competitiveness which is imminent in sports and physical training, as explained above.

Twelve network samples (3rd, 5th and 7th semester classes of students) of physical education departments in Greece were collected: 1) two classes of Athens University (42 and 42 students), 2) four classes of Thessaloniki University (23, 24, 24 and 22 students), 3) a class from Thrace University in Komotini (45 students), 4) five classes of Thessaly University in Trikala (82, 58, 59, 63 and 54 students). Totally, the sample included 538 nodes (265 female and 273 male) aged 19-25 years old. In each class, the students were familiar to each other. Standardized questionnaires were answered by the students regarding relation forms of verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism which are practiced among them in the beginning and in the end of the academic winter semester 2018-2019.

The same questionnaires were answered by the same students at the beginning (2nd week of October) and the end of the semester (2nd week of January) enabling a dynamic (diachronic) analysis of the networks since informal peer interactions during an academic semester can shape negative or positive relationships with leading or isolated classmates (Howe, 2010). The initial and final inquiries have been carried out within the same semester (and not i.e., at the beginning and the end of a whole year or a longer time scale) because after the end of the semester the students choose different directions of specialization and they cease to be mates in the class. As the questionnaires contained network part were named but coded, so that the nodes are recognizable for being analyzed as a node of a network. Therewith, they were encouraged to give sincere answers.

Questionnaire

Validated psychometric questionnaires already used in past studies (Dahling, Whitaker, & Levy, 2009; Espelage & Holt 2001; Infante & Wigley, 1986) were the basis for the network questionnaires used in this particular study (concerning verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism structures) for measuring network indicators (centralities) (s. Hasanagas & Bekiari 2015; 2017; Bekiari & Pachi, 2017; Spanou, Bekiari & Theoharis, 2020).

Concerning the network variables, the verbal aggressiveness scale consisted of 5 items such as “who has ironed you?”, the bullying scale consisted of 5 items such as “who has excluded you?” and the Machiavellian scale consisted of 9 items such as “who do you consider that exploit personal information for his/her own benefit?”. The non-network variables included the personal features of students such as age, gender, social-economic situation etc.

Approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Department of the Physical Education & Sport Science, University of Thessaly, Greece. The students were clarified of the purposes, ethics of the study and their personal data protection, signing consent forms. The 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Tokyo in 2004) was taken into account and not violated by the researchers’ actions.

Statistical analysis

Software Visone 1.1 was used for the calculation of network variables (centralities: in- and out-degree, Katz status, pagerank and authority). Non-network as well as network data were entered and processed in SPSS. Spearmantest has been implemented between time axis (beginning and end of semester) and the network variables in order to detect evolvement as well as between the network variables values in the beginning and the end of semester to examine stability. This bivariate test was preferred to a multivariate analysis, as it is non-parametric and provides clear overview of correlations.

In-depth interviews were used for interpreting quantitative results. Furthermore, it is clarified that permutation techniques (like QAP, ERGM) may be useful for examining correlations between different network ties considering as variables not the centralities of the nodes but the whole networks. This is not the goal of this research, where values of various centralities of nodes (not ties) were correlated with each other.

Results

Descriptive examples

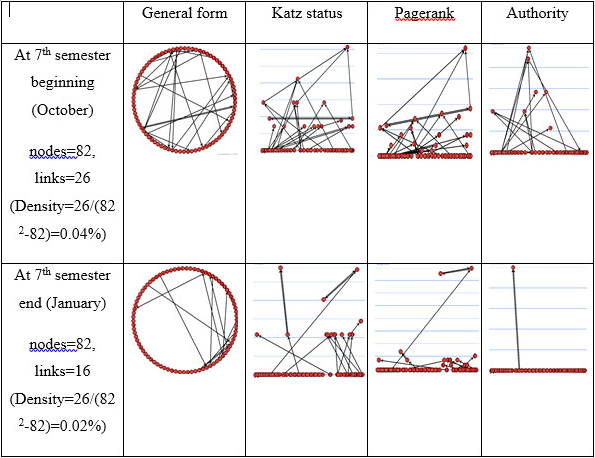

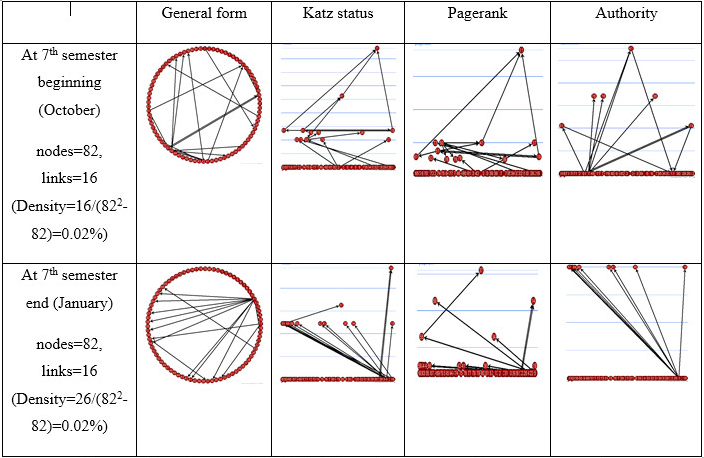

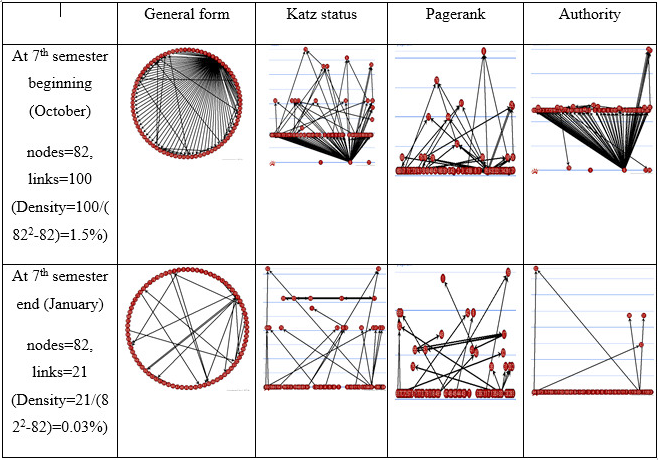

In figures 1, 2 and 3, network examples of verbally aggressive behaviour, bullying and Machiavellian behaviour among students are presented. Specifically, in verbal aggressiveness (fig.1), the density of irony seems to slightly decline from the beginning to the end of the semester (from 0.04% to 0.02%). In bullying (fig.2), the dimension of disseminating negative rumors remains constant (0.02%) from the beginning to the end of the semester. In Machiavellianism (fig.3), the dimension of collecting information for benefit is markedly decreased (from 1.5% to 0.03%).

These descriptive results constitute the first evidence that not all these behavioural forms are characterized by the same frequency and stability. For example, one may be more easily fed up with being ironic to others, disseminating negative rumors remain an easy practice which remains unrelenting while exploiting information for personal benefit quickly loses in effectiveness, as many students realize being exploited and become more careful in their interpersonal contacts.

As for the different types of hierarchies (Katz, pagerank and authority), they seem to be noticeably different to each other synchronically as well as differentiated from the beginning to the end of the semester justifying the necessity of examining the stability (or instability) of the property of victimizer and victim in each one of these relations.

FIGURE 1. Network example: Verbal aggressiveness (irony) network at the department of physical education department, University of Thessaly, Greece

FIGURE 2. Network example: Bullying (dissemination of negative rumors) network at the

department of physical education department, University of Thessaly, Greece

FIGURE 3. Network example: Machiavellianism (collecting information for personal benefit) network at the department of physical education department, University of Thessaly, Greece

Network Analysis

In table 1, it is observable that students tend to practice all dimensions of verbal aggressiveness (0.180 to 0.107) and bullying (0.185 to 0.222) more and more during the semester. They tend to give more and more orders to others (0.062). The rest dimensions of Machiavellian behaviour (-0.154 to -0.073) tend to be weaker in the course of time.

TABLE 1. Dynamic analysis of destructive behaviors practicing

|

Spearman test |

October=1, January=2 |

|

|

Verbal aggressiveness |

making fun (authority) |

,180(**) |

|

,000 |

||

|

threat (indegree) |

,222(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

threat (katz) |

,222(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

sadness (pagerank) |

,061(*) |

|

|

,045 |

||

|

harassment (authority) |

,107(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

Bullying |

exclusion (authority) |

,185(**) |

|

,000 |

||

|

negative rumours (authority) |

,119(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

arguing (authority) |

,162(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

disagreements (authority) |

,068(*) |

|

|

,026 |

||

|

refusing help (authority) |

,222(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

Machiavellianism |

beneficial information (authority) |

-,154(**) |

|

,000 |

||

|

deception (indegree) |

-,062(*) |

|

|

,043 |

||

|

orders (pagerank) |

,062(*) |

|

|

,043 |

||

|

social success (authority) |

-,123(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

welfare (authority) |

-,111(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

beneficial harming (authority) |

-,212(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

exploiting weakness (authority) |

-,073(*) |

|

|

,017 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

The results of table 2 are in accordance with these of table 1. As students tend to practice verbal aggressiveness and bullying to each other, they also tend to become more and more targets of these destructive behaviours (0.060 to 0.148). On the other hand, as Machiavellianism tends to be restricted in the course of time, the less the victimization of this action tends to become (-0.061 to -0.064).

TABLE 2. Dynamic analysis of destructive behaviors targeting

|

Spearman test |

October=1, January=2 |

|

|

Verbal aggressiveness |

negative comments (outdegree) |

,060(*) |

|

,049 |

||

|

making fun (outdegree) |

,123(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

threat (outdegree) |

,210(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

harassment (outdegree) |

,131(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

Bullying |

exclusion (outdegree) |

,195(**) |

|

,000 |

||

|

negative rumours (outdegree) |

,085(**) |

|

|

,005 |

||

|

refusing help (outdegree) |

,148(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

Machiavellianism |

orders (outdegree) |

-,061(*) |

|

,047 |

||

|

social success (outdegree) |

-,150(**) |

|

|

,000 |

||

|

welfare (outdegree) |

-,064(*) |

|

|

,037 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

In table 3, the stability situation of hierarchies is depicted in terms of correlation coefficients. All nodes’ summaries of indegree, pagernak, Katz and authority in all dimensions of aggressiveness are measured in October and January and correlated. The higher the coefficient is, the more stable the hierarchy remains from October to January. Coefficient = 1 would mean that the one who is the most aggressive in October is also the most aggressive in January, the second most aggressive one in October remains the second most aggressive one also in January etc. Coefficient = -1 would mean complete inversion of the hierarchy (the most aggressive one becomes the least aggressive one). The diagonal coefficients (0.512 to 0.604) describe the stability of each dimension of verbal aggressiveness between the beginning (October) and the end (January) of the semester. As shown, the most stable hierarchy is this of threat (0.711) and it seems to be converted even in harassment (0.700). The most unstable hierarchy is this of irony (0.458).

TABLE 3. Stability of verbal aggressiveness practicing (summary of indegree, pagerank, katz and authority).

|

Spearman test |

negative comments |

insulting |

irony |

rudeness |

making fun |

threat |

sadness |

harassment |

|

(in January) |

||||||||

|

negative comments (in October) |

,512(**) |

,523(**) |

,482(**) |

,481(**) |

,508(**) |

,536(**) |

,549(**) |

,556(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

insulting (in October) |

,513(**) |

,584(**) |

,518(**) |

,513(**) |

,616(**) |

,596(**) |

,598(**) |

,608(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

irony (in October) |

,399(**) |

,477(**) |

,458(**) |

,439(**) |

,555(**) |

,454(**) |

,491(**) |

,475(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

rudeness (in October) |

,493(**) |

,528(**) |

,479(**) |

,507(**) |

,574(**) |

,506(**) |

,544(**) |

,556(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

making fun (in October) |

,502(**) |

,504(**) |

,515(**) |

,503(**) |

,631(**) |

,530(**) |

,554(**) |

,544(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

threat (in October) |

,620(**) |

,635(**) |

,567(**) |

,610(**) |

,673(**) |

,711(**) |

,694(**) |

,700(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

sadness (in October) |

,484(**) |

,474(**) |

,433(**) |

,475(**) |

,525(**) |

,516(**) |

,520(**) |

,526(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

harass-ment (in October) |

,596(**) |

,616(**) |

,554(**) |

,588(**) |

,655(**) |

,597(**) |

,584(**) |

,604(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

In table 4, a similar diachronic correlation (0.660 to 0.681) takes place between bullying behaviours (like this carried out in table 5 for the aggressiveness dimensions). The most stable bullying behaviour seems to be refusing help (0.681) while the most unstable and thus, occasional behaviour seems to be arguing (0.464). It is noticeable that there is a strong coefficient (0.730) between exclusion (in October) and refusing help (in January) and a strong coefficient (0.703) between disagreement (in October) and refusing help (in January).

TABLE 4. Stability of bullying practicing (summary of indegree, pagerank, katz and authority).

|

Spearman test |

exclusion |

negative rumours |

arguing |

disagreements |

refusing help |

|

(in January) |

|||||

|

exclusion (in October) |

,660(**) |

,625(**) |

,569(**) |

,693(**) |

,730(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

negative rumours (in October) |

,669(**) |

,629(**) |

,551(**) |

,660(**) |

,697(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

arguing (in October) |

,543(**) |

,495(**) |

,464(**) |

,545(**) |

,538(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

disagreements (in October) |

,681(**) |

,604(**) |

,572(**) |

,671(**) |

,703(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

refusing help (in October) |

,611(**) |

,608(**) |

,525(**) |

,614(**) |

,681(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

In table 5, in the diagonal coefficients a wide gradation of stability (from 0.193 to 0.628) appears. The most stable role appears to be the one of stabbing in the back (0.628) while the most unstable Machiavellian behaviour is this of collecting information for benefit (0.193). Another role which is quite unstable diachronically is the harming for benefit (0.240). The other hierarchies of practicing Machiavellianism seem to be relatively stable but their coefficients (0.405-0.567) are lower than these of bullying (0.463-0.681 in table 4). It is noticeable that there are certain strong coefficients between different dimensions of Machiavellianism, e.g. the deception and back-stabbing (0.643) or exploiting weakness and beneficial harming (0.543).

TABLE 5. Stability of Machiavellianism practicing (summary of indegree, pagerank, katz and authority).

|

Spearman test |

beneficial information |

deception |

orders |

control |

social success |

welfare |

beneficial harming |

exploiting weakness |

back- stabbing |

|

(in January) |

|||||||||

|

beneficial information (in October) |

,193(**) |

,122(**) |

,081 |

,143(**) |

,137(**) |

,094(*) |

,185(**) |

,119(**) |

,114(**) |

|

,000 |

,005 |

,060 |

,001 |

,001 |

,030 |

,000 |

,006 |

,008 |

|

|

deception (in October) |

,462(**) |

,567(**) |

,442(**) |

,544(**) |

,438(**) |

,505(**) |

,581(**) |

,603(**) |

,643(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

orders (in October) |

,482(**) |

,450(**) |

,476(**) |

,494(**) |

,368(**) |

,448(**) |

,469(**) |

,475(**) |

,484(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

control (in October) |

,477(**) |

,519(**) |

,506(**) |

,598(**) |

,445(**) |

,483(**) |

,570(**) |

,605(**) |

,580(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

social success (in October) |

,452(**) |

,454(**) |

,448(**) |

,501(**) |

,445(**) |

,449(**) |

,482(**) |

,506(**) |

,518(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

welfare (in October) |

,263(**) |

,408(**) |

,371(**) |

,320(**) |

,353(**) |

,405(**) |

,423(**) |

,339(**) |

,379(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

beneficial harming (in October) |

,218(**) |

,132(**) |

,079 |

,133(**) |

,144(**) |

,098(*) |

,240(**) |

,242(**) |

,212(**) |

|

,000 |

,002 |

,068 |

,002 |

,001 |

,023 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

exploiting weakness (in October) |

,386(**) |

,434(**) |

,351(**) |

,434(**) |

,315(**) |

,380(**) |

,543(**) |

,472(**) |

,459(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

back-stabbing (in October) |

,465(**) |

,480(**) |

,425(**) |

,499(**) |

,426(**) |

,434(**) |

,596(**) |

,575(**) |

,628(**) |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

In table 6, a quite weak stability (0.161 to 0.141) appears in victimization of verbal aggressors. Comparing table 6 (targeting) with table 3 (practicing), the coefficients of former are much weaker than these of latter. It is noticeable that threat at the beginning seems to dynamically result in insulting (0.418). Victimization of harassment (0.013 insign.) seems to be totally discontinuous from the beginning to the end of the semester.

TABLE 6. Stability of verbal aggressiveness targeting (outdegree)

|

Spearman test |

negative comments |

insulting |

irony |

rudeness |

making fun |

threat |

sadness |

harassment |

|

(in January) |

||||||||

|

negative comments (in October) |

,161(**) |

,098(*) |

,044 |

,033 |

,069 |

,063 |

,108(*) |

,089(*) |

|

,000 |

,023 |

,306 |

,448 |

,108 |

,143 |

,013 |

,039 |

|

|

insulting (in October) |

,142(**) |

,111(*) |

,073 |

,043 |

,101(*) |

,121(**) |

,068 |

,129(**) |

|

,001 |

,010 |

,092 |

,316 |

,019 |

,005 |

,113 |

,003 |

|

|

irony (in October) |

,210(**) |

,119(**) |

,136(**) |

,129(**) |

,034 |

,022 |

,156(**) |

,009 |

|

,000 |

,006 |

,002 |

,003 |

,433 |

,610 |

,000 |

,840 |

|

|

rudeness (in October) |

,213(**) |

,117(**) |

,138(**) |

,139(**) |

,133(**) |

,142(**) |

,153(**) |

,161(**) |

|

,000 |

,007 |

,001 |

,001 |

,002 |

,001 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

making fun (in October) |

,155(**) |

,110(*) |

,113(**) |

,085(*) |

,141(**) |

,090(*) |

,122(**) |

,126(**) |

|

,000 |

,011 |

,009 |

,049 |

,001 |

,037 |

,005 |

,003 |

|

|

threat (in October) |

,354(**) |

,418(**) |

,352(**) |

,384(**) |

,318(**) |

,313(**) |

,378(**) |

,031 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,477 |

|

|

sadness (in October) |

,304(**) |

,288(**) |

,241(**) |

,258(**) |

,233(**) |

,223(**) |

,312(**) |

,067 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,120 |

|

|

harassment (in October) |

,321(**) |

,369(**) |

,295(**) |

,319(**) |

,251(**) |

,213(**) |

,326(**) |

,013 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,770 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

The stability of bullying victimization (table 7) seems also to be quite weak (0.344-0.090) as the stability of verbal aggressiveness victimization (table 6). Especially in case of arguing (which is not necessarily always regarded as negative as the other dimensions of bullying), a statistically insignificant coefficient appears (0.061). Particularly, exclusion at the beginning of semester tends strongly to result in arguing (0.411) and in refusing help (0.416) at the end of the semester.

TABLE 7. Stability of bullying targeting (outdegree).

|

Spearman test |

exclusion |

negative rumours |

arguing |

disagreements |

refusing help |

|

(in January) |

|||||

|

exclusion (in October) |

,344(**) |

,072 |

,411(**) |

,089(*) |

,416(**) |

|

,000 |

,096 |

,000 |

,040 |

,000 |

|

|

negative rumours (in October) |

,149(**) |

,136(**) |

,071 |

,162(**) |

,066 |

|

,001 |

,002 |

,099 |

,000 |

,126 |

|

|

arguing (in October) |

,149(**) |

,102(*) |

,061 |

,101(*) |

,042 |

|

,001 |

,018 |

,158 |

,019 |

,327 |

|

|

disagreements (in October) |

,139(**) |

,139(**) |

,098(*) |

,171(**) |

,107(*) |

|

,001 |

,001 |

,023 |

,000 |

,013 |

|

|

refusing help (in October) |

,167(**) |

,102(*) |

,109(*) |

,131(**) |

,090(*) |

|

,000 |

,018 |

,012 |

,002 |

,037 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 8 also presents a weak diachronic stability of victimization in Machiavellianism between the beginning and the end of the semester (0.096 to -0.018) in contrast to the much stronger stability of victimizing presented in table 5.

TABLE 8. Stability of Machiavellianism targeting (outdegree)

|

Spearman test |

beneficial information |

deception |

orders |

control |

social success |

welfare |

beneficial harming |

exploiting weakness |

back stabbing |

|

(in January) |

|||||||||

|

beneficial information (in October) |

,096(*) |

,047 |

,089(*) |

,002 |

,109(*) |

,156(**) |

,083 |

,054 |

,063 |

|

,027 |

,275 |

,038 |

,960 |

,011 |

,000 |

,056 |

,215 |

,146 |

|

|

deception (in October) |

,049 |

,296(**) |

,095(*) |

,353(**) |

,072 |

,093(*) |

,014 |

,306(**) |

,379(**) |

|

,252 |

,000 |

,027 |

,000 |

,094 |

,031 |

,744 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

orders (in October) |

,131(**) |

,081 |

,134(**) |

,021 |

,140(**) |

,185(**) |

,127(**) |

,092(*) |

,034 |

|

,002 |

,059 |

,002 |

,624 |

,001 |

,000 |

,003 |

,034 |

,435 |

|

|

control (in October) |

,088(*) |

,329(**) |

,121(**) |

,378(**) |

,102(*) |

,120(**) |

,040 |

,345(**) |

,427(**) |

|

,042 |

,000 |

,005 |

,000 |

,018 |

,005 |

,349 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

social success (in October) |

,109(*) |

,292(**) |

,099(*) |

,317(**) |

,179(**) |

,205(**) |

,064 |

,306(**) |

,404(**) |

|

,011 |

,000 |

,021 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,137 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

|

welfare (in October) |

,137(**) |

,099(*) |

,127(**) |

,035 |

,172(**) |

,269(**) |

,126(**) |

,093(*) |

,064 |

|

,001 |

,021 |

,003 |

,424 |

,000 |

,000 |

,003 |

,031 |

,136 |

|

|

beneficial harming (in October) |

,016 |

-,009 |

,077 |

,017 |

,035 |

,047 |

,030 |

,010 |

,005 |

|

,706 |

,836 |

,073 |

,698 |

,416 |

,279 |

,487 |

,823 |

,902 |

|

|

exploiting weakness (in October) |

,089(*) |

,040 |

,167(**) |

,043 |

,140(**) |

,183(**) |

,073 |

,029 |

,055 |

|

,039 |

,354 |

,000 |

,319 |

,001 |

,000 |

,093 |

,498 |

,203 |

|

|

back stabbing (in October) |

,008 |

-,018 |

,069 |

-,018 |

,039 |

,004 |

,055 |

-,013 |

-,018 |

|

,857 |

,669 |

,108 |

,683 |

,369 |

,933 |

,207 |

,757 |

,683 |

|

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Discussion

Aim of this research was the diachronic analysis of verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism among students of all Physical Education departments of Greece (University of Athens, Thessaly, Thessaloniki and Thrace). This analysis has been distinguished: a) In exploration of evolvement of these behavioural phenomena diachronically. b) In control of hierarchical stability between the beginning and the end of the semester.

Specifically, the evolvement of practicing such destructive behaviours may reasonably be attributed to students’ familiarity (daily class attendance) during the semester. Thus, they can exert more easily verbal aggressiveness, bullying and give orders to each other considering their tolerance. Nevertheless, the rest dimensions of Machiavellianism (apart from giving orders) seem to be hindered by the familiarisation, as each one becomes more and more aware of the exploitative tactics of the others. Relevant studies have been carried out (Bekiari et al., 2019; Bekiari & Pachi, 2017; Bekiari & Spanou, 2018).

Concerning the evolvement of becoming a target of destructive behaviours, the dynamics is similar to this of practicing them, which may also be attributed to reasons of familiarisation (the more familiar one becomes to each other, the more encouraged the others are to practice such behaviours and the more tolerant one becomes to them) (cf. Bekiari, Pachi & Hasanagas, 2017). However, the Machiavellian dimension of giving orders to the others, though it proliferates by the offenders, seems to decrease as direct received action by the victims. This can be regarded as an effect of more and more selective perception of being ordering during the semester while simultaneously individuals characterized by accumulative potential of giving orders are more and more distinct (cf Spanou, Bekiari & Theocharis, 2020). This can be understood as an effect of their daily class attendance promoting the accumulation of knowledge about their co-students’ personalities.

Concerning the stability of practicing verbal aggressiveness between the beginning and the end of the semester, the fact that threat appears to be quite stable means that the most susceptible students to threat others in October strongly tend to remain the most susceptible ones in threat in January. However, the most unstable hierarchy is this of irony. Namely, the most ironic students in October are not so likely to be also the most ironic ones in January. In other words, the threat is a behaviour which can change with much more difficultly than the irony. All other dimensions of aggressive behaviour are at a middle level of stability.

Why is threat so unchangeable and irony so changeable? An interpretation of this difference can be based on the fact that threat is a quite unacceptable action so these who practice it, have a deep-rooted mentality of aggressiveness. Not everyone can threat and threat is not an occasional but rather a permanent feature of a person (it seems to be converted even in harassment).

On the contrary, irony seems to be an occasional pattern of aggressiveness which many students (even perhaps the friendliest ones) may practice. Irony is not as disturbing or troubling as threat. Irony can even be regarded as a joke or a friendly tease with communicative benefits (Burgers et al., 2016).

Consequently, the threatening students tend to be the same while ironic students may be many of them alternatively and occasionally. Similar studies have been carried regarding threat and irony (e.g., Hasanagas, Bekiari & Vasilos, 2017).

The most stable dimension of bullying behaviour seems to be refusing help while the least stable -and thus occasional- behaviour seems to be arguing. This can be attributed to the fact that refusing help constitutes a manifested and quite provocative or asocial action. Therefore, it can mainly be exerted by a determined and permanent bully (cf Bekiari & Pachi, 2017). On the other hand, although argument is often described as a dimension of bullying (Difazio et al., 2019), individuals who come in conflicts by the using of arguments may exhibit equal power (not power imbalance) since they have equal opportunities of developing arguments (Cascardi et al., 2014). Thus, arguing may take place even among the politest friends or in a friendly manner. All other behavioural patterns of bullying appear to be at a middle level of stability.

A noticeable difference of bullying stability from verbal aggression stability lies in that certain bullying dimensions occurring in October may even be correlated with different bullying dimensions occurring in January. Such different dimensions may even be correlated with each other with coefficients higher than these between same dimensions at the two time points. A characteristic example of such a strong coefficient between different dimensions at the two different time points is the strong relation between exclusion and refusing help. This can be understood as an evolvement of exclusion (in October) into refusing help (in January), which as aforementioned seems to be a core dimension of bullying. An additional example of such an evolvement is the strong correlation between disagreement (in October) and refusing help (in January). Thus, refusing help seems to be a final phase of core bullying behaviour.

The fact that the most stable Machiavellian role appears to be the one of back-stabbing while the most unstable Machiavellian behaviour is this of collecting information for benefit can reasonably be understood as a result of the fact that the back-stabbing behaviour constitutes a quite cost-effective tactic (high target benefit in an easy way) while benefit by information has an occasional character (neither beneficial information is available nor students can develop mechanisms of information access and exploitation) (cf Spanou, Bekiari & Theocharis, 2020).

Another role which seems to be quite unstable diachronically is to harm for benefit. This can be interpreted similarly, as long as the opportunities of beneficial harming are not so frequent in the students’ community. The other hierarchies of practicing Machiavellianism seem to be relatively stable, which means that the Machiavellian victimizers tend to remain the same ones during the semester. However, their coefficients are lower than these of bullying which indicates that Machiavellianism is more occasional than bullying. Apart from that, there are also external accumulations of Machiavellian behaviours. For example, the deception (in October) appears to indicate a predisposition or to be a preparatory work for back-stabbing (in January). Similarly, exploiting weakness (in October) seems to be a preparatory work for beneficial harming (in January).

The weak stability of victimization in verbal aggressiveness implies that the victims at the beginning of the semester are quite different from the ones at the end. Especially, the discontinuity of victimization of harassment indicates that this dimension of verbal aggressiveness seems to be quite occasional and unpredictable. Comparing stability of targeting with stability of practicing verbal aggressiveness, the former appears to be much weaker than the latter. This means that the victims are much less stable diachronically than the victimizers. This can be attributed to the fact that at the university there is no everyday examination procedure which could establish “unrespectable” and “respectable” students as well as to the fact that the students who have vulnerable characteristics (e.g. low social class, deviant physical appearance etc) try to cover it or to be more careful in selecting their companionships. Thus, it is difficult to become stable targets.

On the other hand, at this age most students have stabilized their personality, so the aggressive ones tend to remain aggressive. Additionally, the fact that threat at the beginning seems to dynamically result in insulting is evidence that especially threat should be taken seriously by the victims. As for the arguing, its insignificance between October and January appears to be even accidental (Cascardi et al., 2014) between the beginning and the end of the semester, being considered as an intellectual interaction rather than as a means of imposition. The comparison between practicing and becoming a target of bullying reveals once again the contrast between the stable role of victimizer and the unstable role of victim. The interpretation of this can also be attributed to the reasons same to these which have been discussed in verbal aggressiveness targeting.

Especially, regarding exclusion at the beginning of semester, it seems to be the most serious dimension of bullying as it strongly tends to lead to arguing and to refusing help at the end of the semester. In other words, the exclusion is a presage of further abuse, or inversely, the arguing or the refusing of help can be regarded as a normative extension of exclusion, meaning the expelling of a social milieu or of the value system of a group.

The contrast between the weak diachronic stability of being a victim of Machiavellianism and the much stronger stability of practicing Machiavellianism can be interpreted similarly as in the case of contrast between bullying targeting and practicing. Apart from that, the dupe is not dupe forever, as the students learn whom they should trust or not (cf Bekiari, Deliligka & Koustelios, 2017; Bekiari & Spyropoulou, 2016).

It is remarkable that controlling and pointing out social success tend to result in back-stabbing. Thus, not all dimensions of verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism evolve equally and not all of them are of similar importance. Certain of them belong to the core of these behaviours while others are more occasional. Apart from that, the prevention against such behaviours tends to be enhanced and certain behaviours also have a perceptional character.

A limitation of this research lies in the fact that it is confined on physical education students. However, a challenge for future research is to extend this exploration to other departments (medicine, pedagogic etc) as well as to find out possible new forms of verbal aggressiveness, bullying or Machiavellianism in these departments and tactics to prevent these behaviours. Comparative analyses among different departments and macro-diachronic studies (e.g., evolvement of such behaviours from primary school to higher education) would also be desirable.

Conclusion

Diachronic analysis of verbal aggressiveness, bullying and Machiavellianism among students of all Physical Education departments has been carried out regarding their evolvement diachronically and the stability of victimizers and victims during the semester. The strengthening of practicing destructive behaviours may reasonably be attributed to the fact that students become more and more familiar to each other during the semester. However, the Machiavellian dimension of giving orders to others, though it proliferates by the offenders, seems to decrease as direct received action by the victims, which may be attributed to perceptional differentiation.

Concerning the stability of these behaviours between the beginning and the end of the semester, the threat appears to be quite stable and unchangeable in contrast to the irony, as not everyone can threat and threat is not an occasional but rather a permanent feature of a person (it seems to be converted even in harassment) while irony seems to be an occasional pattern of aggressiveness appearing even among the friendliest ones. Most stable bullying behaviour seems to be refusing help, as it is quite asocial and thus, it can be practiced by extrovert bullies while the least stable one is the arguing, which is quite mild and occasional.

Additionally, evolvements of exclusion into refusing help and of disagreement into refusing help have been observed. In other words, refusing help appears to be a final phase of core bullying behaviour. The most stable Machiavellian dimension is back-stabbing (as a quite cost-effective tactic) while the most unstable is this of collecting information (or harm) for benefit, which can succeed only occasionally. In general, Machiavellian victimizers tend to remain the same ones during the semester, however, more occasionally than bullying victimizers.

Apart from that, deception indicates a predisposition for back-stabbing and exploiting weakness seems to be a preparatory work for beneficial harming. There is a remarkably weak stability of victimization in verbal aggressiveness. Especially harassment seems to be quite occasional and unpredictable. Victims are much less stable diachronically than the victimizers, as at the university there are no everyday examination procedure which could establish “unrespectable” and “respectable” students and students with vulnerable characteristics try to cover them or to be more careful in selecting friends. Arguing appears to be accidental. Exclusion is a presage of further abuse (e.g. refusing of help). Controlling and pointing out social success tend to result in back-stabbing.

References

Al-Ali, M. M., Singh, A. P., & Smekal, V. (2011). Social anxiety in relation to social skills, aggression, and stress among male and female commercial institute students. Education, 132(2), 351-361.

Allanson, P. B., Lester, R. R., & Notar, C. E. (2015). A History of Bullying. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 2(12), 31-36.

Andreou, E., Tsermentseli, S., Anastasiou, O., & Kouklari, E. C. (2021). Retrospective accounts of bullying victimization at school: Associations with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and post-traumatic growth among university students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(1), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s.40653-020-00302-4

Bekiari, A. (2012). Perceptions of Instructors’ Verbal Aggressiveness and Physical Education Students’ Affective Learning. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 115(1), 325-335. https://doi.org/10.2466/06.11.16.PMS.115.4.325-335.

Bekiari, A., Deliligka, S., & Koustelios, A. (2017). Examining Relations of Aggressive Communication in Social Networks. Social Networking, 6(1), 38-52. https://doi.org/ 10.4236/sn.2017.61003

Bekiari, A., Deliligka, S., Vasilou, A., & Hasanagas, N. (2019). Socio-educational Determinants of “Bad Behaviour” of Students: A Comparative Analysis among Primary, Secondary, and High School. The International Journal of Learner Diversity and Identities, 26(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0128/CGP/v26i01/1-19

Bekiari, A., & Hasanagas, N. (2015). Verbal Aggressiveness Exploration through Complete Social Network Analysis: Using Physical Education Students’ Class as an Illustration. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 3(3), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v3i3.729

Bekiari, A., & Hasanagas, N. (2016). Suggesting indicators of superficiality and purity in verbal aggressiveness: An application in adult education class networks of prison inmates. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(03), 279-292. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.43035

Bekiari, A., Hasanagas, N., Theoharis, D., Kefalas, I., & Vasilou, A. (October 2015). The Role of Mathematical Object and the Educational Environment to Students’ Interpersonal Relationships: An Application of Full Social Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the 32nd Congress Greek Mathematical Society (with International Participation), Kastoria pp. 799-812.

Bekiari, A., Kokaridas, D., & Sakellariou, K. (2005). Verbal Aggressiveness of Physical Education Teachers and Students’ Self-Reports of Behaviour. Psychological Reports, 96(2), 493-498. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.96.2.493-498

Bekiari, A., Kokaridas, D., & Sakellariou, K. (2006). Associations of Students’ Self-Report of Their Teacher’s Verbal Aggression, Intrinsic Motivation, and Perceptions of Reasons for Discipline in Greek Physical Education Classes. Psychological Reports, 98(2), 451-461. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.98.2.451-461

Bekiari, A. & Pachi, V. (2017). Insights into Bullying and Verbal Aggressiveness through Social Network Analysis. Journal of Computer and Communications, 5(09), 79-101. https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2017.59006

Bekiari, A., Pachi, V., & Hasanagas, N. (2017). Investigating bullying determinants and typologies with social network analysis. Journal of Computer and Communications, 5(07), 11-27. https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2017.57002

Bekiari, A., Perkos, S., & Gerodimos, V. (2015). Verbal Aggression in Basketball: Perceived Coach Use and Athlete Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 15(1), 96-102. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2015.01016

Bekiari, A., & Spanou, K. (2018). Machiavellianism in Universities: Perceiving Exploitation in Student Networks. Social Networking, 7(1), 19-31. https://doi.org/10.4236/sn.2018.71002

Bekiari, A., & Spyropoulou, S. (2016). Exploration of Verbal Aggressiveness and Interpersonal Attraction through Social Network Analysis: Using University Physical Education Class as an Illustration. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(06), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.46016

Brandes, U., & Wagner, D. (2004). Analysis and visualization of social networks. In Graph drawing software (pp. 321-340). Germany: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Burgers, C., Konijn, E. A., & Steen, G. J. (2016). Figurative framing: Shaping public discourse through metaphor, hyperbole, and irony. Communication Theory, 26(4), 410-430. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12096

Cascardi, M., Brown, C., Iannarone, M., & Cardona. (2014). The problem with overly broad definitions of bullying: Implications for the schoolhouse, the statehouse, and the ivory tower. Journal of School Violence, 13(3), 253-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2013.846861

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism Scale. Journal of Management, 35(2), 219-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318618

Difazio, R., Vessey, J., Buchko, O., Chetverikov, D., Sarkisova, V., & Serebrennikova, N. (2019). The incidence and outcomes of nurse bullying in the Russian Federation. International Nursing Review, 66(1), 94-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12479

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2001). Bullying and Victimization during Early Adolescence: Peer Influences and Psychosocial Correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse 2(2-3), 123-142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v02n0208

Hasanagas, N., & Bekiari, A. (2015). Depicting Determinants and Effects of Intimacy and Verbal Aggressiveness Target through Social Network Analysis. Sociology Mind, 5(3), 162-175. https://doi.org/10.4236/sm.2015.53015

Hasanagas, N., & Bekiari, A. (2017). An Exploration of the Relation between Hunting and Aggressiveness: Using Inmates Networks at Prison Secondary School as an Illustration. Social Networking, 6(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.4236/sn.2017.61002

Hasanagas, N., Bekiari, A., & Vasilos, P. (2017). Friendliness to animals and verbal aggressiveness to people: Using prison inmates education networks as an illustration. Social Networking, 6(3), 224-238. https://doi.org/10.4236/sn.2017.63015

Howe, C. (2010). Peer groups and children’s development. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Infante, D. A., & Wigley III., C. J. (1986). Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Communications Monographs, 53(1), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758609376126

Jünger, M., & Mutzel, P. (2012). Graph drawing software. Springer Science & Business Media.

Kotroyannos, D., & Tzagkarakis, S. I. (2021). Machiavelli against Machiavellianism: The New “arte dello stato”. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, sectio K-Politologia, 27(2), 7-14. https://doi.org/10.17951/k.2020.27.2.7-14

Myers, S. A., Brann, M., & Martin, M. M. (2013). Identifying the content and topics of instructor use of verbally aggressive messages. Communication Research Reports, 30(3), 252-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2013.806260

Otte, S., Streb, J., Rasche, K., Franke, I., Segmiller, F., Nigel, S., ... & Dudeck, M. (2019). Self-aggression, reactive aggression, and spontaneous aggression: Mediating effects of self-esteem and psychopathology. Aggressive behavior, 45(4), 408-416. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21825

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and violent behaviour, 15(2), 112-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Spanou, K., Bekiari, A., & Theocharis, D. (2020). Bullying and Machiavellianism in University through Social Network Analysis. International Journal of Sociology, 78(1), e151. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2020.78.1.18.096

Staunton, T. V., Alvaro, E. M., & Rosenberg, B. D. (2020). A case for directives: Strategies for enhancing clarity while mitigating reactance. Current Psychology, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00588-0

Syrmpas, I., & Bekiari, A. (2018). Differences between leadership style and verbal aggressiveness profile of coaches and the satisfaction and goal orientation of young athletes. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18(2), 1008-1015. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2018.s2149

Tang, T. L. P., Chen, Y. J., & Sutarso, T. (2008). Bad apples in bad (business) barrels: The love of money, Machiavellianism, risk tolerance and unethical behaviour. Management Decision, 46(2), 243-263. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740810854140

Theoharis, D., & Bekiari, A. (2018). Dynamic Analysis of Verbal Aggressiveness Networks in School. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 6(01), 14-28. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2018.61002

Webb, J. R., Dula, C. S., & Brewer, K. (2012). Forgiveness and aggression among college students. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 14(1), 38-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2012.642669

World Medical Association. (1975). Declaration of Helsinki: recommendations guiding medical doctors in biomedical research involving human subjects. World Medical Association.

Young-Jones, A., Fursa, S., Byrket, J. S., & Sly, J. S. (2015). Bullying affects more than feelings: the long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Social psychology of education, 18(1), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9287-1

Zettler, I. & Solga, M. (2013). Not enough of a ‘dark’ trait? Linking Machiavellianism to job performance. European Journal of Personality, 27(6), 545-554. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1912

Contact address: Kyriaki Spanou. University of Thessaly, Department of Physical Education & Sport Science, Karyes, Trikala 42100, Grece. E-mail: kyrspanou@uth.gr.

1(1) Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the academics and to the students who collaborated in this research project.

Funding: This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund- ESF) through the Operational Programme «Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning» in the context of the project “Strengthening Human Resources Research Potential via Doctorate Research” (MIS-5000432), implemented by the State Scholarships Foundation (IKY).

2()