Another brick in the wall? The extension of compulsory education in the contemporary education debate

¿Another brick in the wall? La ampliación de la educación obligatoria en el debate educativo contemporáneo

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-411-719

Laura Fontán de Bedout

Universitat de Barcelona

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5727-3902

Eric Ortega González

Universitat de Barcelona

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6747-0336

Belén Sánchez García

Universitat de Barcelona

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7067-5195

Abstract

The expansion of compulsory education has been promoted internationally as a strategy to improve access to and equity in education. However, its effects vary depending on the context and do not always meet initial expectations. This study conducts a systematic review of the existing literature with the aim of analyzing its main implications worldwide. To this end, 83 documents were reviewed from the databases Dialnet, ERIC, APA-PsycInfo, and Scopus, selected for addressing the expansion of compulsory education as one of their main thematic focuses, rather than merely as the context of their research. The methodology combined a descriptive quantitative analysis and a qualitative categorization of the content into four dimensions: educational, socio-political, economic, and personal, ensuring data triangulation.

The results show that the expansion of compulsory education has mixed effects. At the educational level, expansion improves access and training, but inequalities in quality, coverage, and equity persist. At the social and political level, it does not guarantee effective inclusion or greater mobility. At the economic level, it can contribute to growth by increasing human capital, although doubts arise about its financial sustainability. At the personal level, educational benefits are identified for some students, while others experience school fatigue or demotivation.

It is concluded that the expansion of compulsory education alone does not ensure improvements in equity or quality. Its effectiveness depends on complementary policies that guarantee resources, inclusive pedagogical strategies, and support for students. To be an effective tool for equity, it must focus on the quality of teaching and the diversity of student trajectories, avoiding being merely a formal extension of schooling.

Keywords:

Compulsory Education, Educational Legislation, Equal Education, Public Schools, School Policy, School Registration

Resumen

La expansión de la educación obligatoria ha sido promovida internacionalmente como una estrategia para mejorar el acceso y la equidad educativa. Sin embargo, sus efectos varían según el contexto y no siempre responden a las expectativas iniciales. Este estudio realiza una revisión sistemática de la literatura existente con el objetivo de analizar sus principales implicaciones a nivel mundial. Para ello, se revisaron 83 documentos en las bases de datos Dialnet, ERIC, APA-PsycInfo y Scopus, seleccionados por abordar la expansión de la educación obligatoria como uno de sus ejes temáticos principales, y no meramente como el contexto de sus investigaciones. La metodología ha combinado un análisis cuantitativo descriptivo y una categorización cualitativa del contenido en cuatro dimensiones: educativa, socipolítica, económica y personal, garantizando, además, la triangulación de datos.

Los resultados muestran que la expansión de la educación obligatoria tiene efectos mixtos. En el plano educativo, la expansión mejora el acceso y la formación, pero persisten desigualdades en calidad, cobertura y equidad. A nivel social y político, no se garantiza una inclusión efectiva ni una mayor movilidad. En el plano económico, puede contribuir al crecimiento mediante el aumento del capital humano, aunque surgen dudas sobre su sostenibilidad financiera. Finalmente, a nivel personal, se identifican beneficios formativos para algunos estudiantes, mientras que otros experimentan fatiga escolar o desmotivación.

Se concluye así que la expansión de la educación obligatoria, por sí sola, no asegura mejoras en equidad ni calidad. Su efectividad depende de políticas complementarias que garanticen recursos, estrategias pedagógicas inclusivas y apoyo a los estudiantes. Para que sea una herramienta efectiva de equidad, debe enfocarse en la calidad de la enseñanza y la diversidad de trayectorias estudiantiles, evitando ser solo una extensión formal de la escolarización.

Palabras clave:

Educación Obligatoria, Legislación Educativa, Igualdad Educativa, Educación pública, Política Educativa, Matriculación EscolarIntroduction

Compulsory education has, since its inception, served as a key political and social instrument, closely tied to the formation of modern nation-states and the configuration of citizenship. In Europe, although its implementation varied across contexts, it was in most cases promoted to foster literacy, moral instruction, and the adaptation of young people to the productive and institutional demands of the nation-state (Paglayan, 2022). In the Spanish case, the Moyano Act of 1857 was the first comprehensive education law to declare primary education compulsory, though it lacked the necessary resources to ensure effective enforcement (Sevilla, 2007). It was not until well into the twentieth century—first with the General Education Act of 1970 and later with the LOGSE of 1990—that a more extensive and articulated system of compulsory schooling was consolidated, currently encompassing the age range from 6 to 16.

In recent decades, the concept of compulsory education has expanded both in temporal scope and in its pedagogical and social significance (Gimeno, 2000). Beyond its legal framework, compulsory schooling has often been understood as a mechanism for structuring of individuals—one that determines not only what should be learned, but also for how long and under which institutional arrangements (Bernal & Martín, 2001). In this sense, contemporary compulsory education systems operate at the intersection of pedagogical, social, and economic debates, shaped by both national actors and international organizations (Verger et al., 2018). As a result, the boundaries, aims, implementation strategies, and particularly the duration of compulsory education remain subject to ongoing revision.

This revisionist trend has become particularly evident in recent

decades, with international organizations such as the OECD promoting a

general orientation toward the extension of compulsory education—raising

both the minimum and maximum age limits (OECD, 2022). From a comparative

perspective, various countries have opted to extend compulsory schooling

at both ends of the educational trajectory:

Unsurprisingly, in a globalized context where international organizations exert significant influence on educational policy, Spain has not remained untouched by these debates. This is reflected in the 2023 report of the State School Council, which, among its proposals for improving education, called for the educational community to debate the extension of compulsory schooling and training to the age of 18 (Marín, 2023).

Regardless of the specific form such an extension may take, these measures—implemented in some countries gradually and often without systemic coordination with other educational reforms—pursue a variety of objectives (Gimeno, 2012). Chief among them are reducing school dropout rates, strengthening the right to education, enhancing productivity, and closing the gender gap in education. Moreover, such decisions affect multiple dimensions of both the educational system and society at large (Flach, 2009): from fostering lifelong learning and restructuring educational stages to teacher preparation, transitions across levels, and labor market integration, to name only a few.

It is particularly striking that, in the current geopolitical context, many of the debates surrounding the extension of compulsory education are taking place simultaneously with the rise of anarcho-liberal and minarchist discourses—embodied by figures such as Javier Milei and Elon Musk—that advocate minimizing the role of the state in citizens’ lives. This reveals a paradox: while certain sectors call for expanding the right to education through greater state intervention, others promote a drastic reduction of such intervention, including—unsurprisingly—in the field of education (Dale, 2025).

Beyond this ideological tension, there is little doubt that the extension of compulsory education has become one of the central issues in today’s educational debate. Nevertheless, numerous open questions remain, and the research published on this topic continues to be extraordinarily heterogeneous. This diversity has produced frequently contradictory results, making it a genuine challenge for researchers to identify the arguments, justifications, and critiques advanced within this debate. Added to this is the multiplicity of terms and meanings employed to address the same issue, which further magnifies to its complexity and the sense of uncertainty surrounding it.

With the aim of bringing greater clarity to this landscape, the present article seeks to respond, from a primarily pedagogical perspective that nonetheless remains attentive to other approaches, to the question of the educational, sociopolitical, economic, and personal implications of the global expansion of compulsory education. The decision of these implications reflects the need to understand the phenomenon from a multidimensional standpoint. From an educational perspective, the extension compels a reconsideration of the meaning, purposes, and contents of the educational system. At the sociopolitical level, it reflects both the degree of the state’s commitment to the right to education and to the construction of citizenship, as well as the distribution of opportunities and the reproduction or transformation of inequalities resulting from legislative and administrative decisions that shape the institutional design of educational systems and the role of public and private actors. The economic implications, in turn, concern both the costs and benefits of extending educational time and its function within the logics of human capital and productivity. Finally, the personal consequences point to the impact of greater schooling on individuals’ subjectivity, life course, and life projects.

Through this multidimensional articulation, which makes it possible to assess more clearly the scope and limits of extending compulsory education, our aim is to contribute to a more robust and well-grounded understanding of a phenomenon that, far from being resolved, continues to pose key challenges and dilemmas for both policy and educational research.

Methodology

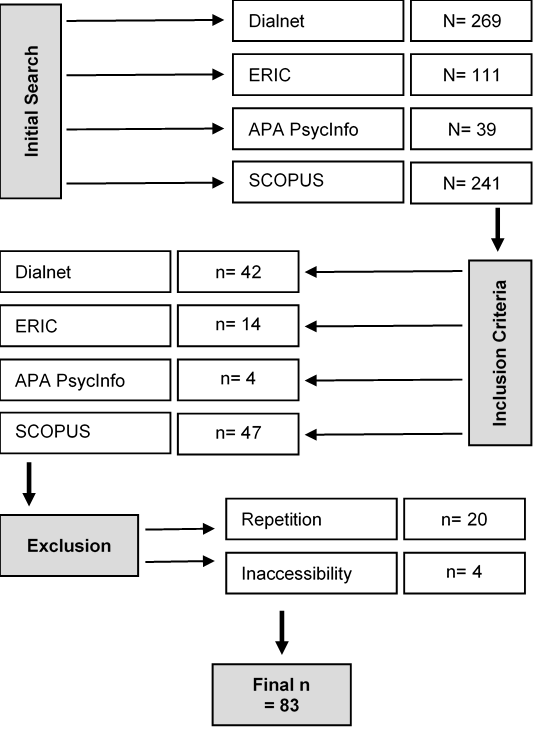

To address the research question outlined above, a systematic literature review was conducted. This methodological approach provides a comprehensive overview of a specific topic—in this case, the expansion of compulsory education from a pedagogical perspective—while also allowing for the examination of particular aspects that are especially relevant to the field of study (Paul & Barrari, 2022). Figure I below summarizes the different phases of the review process.

Figure I. Systematic review process

Source: Own elaboration

For the review, an initial search was carried out that included all

scientific articles and indexed documents containing in their title,

keywords, or abstract the concept of expansion or extension of

compulsory education in four of the most significant and widely used

databases in the field of education: Dialnet, ERIC, APA-PsycInfo, and

Scopus. No restrictions were applied regarding the year of

publication—all publications up to 2024 were considered—nor regarding

language. The search was conducted in both Spanish—

In a second stage, after screening titles and abstracts, those scientific articles were selected in which the extension of compulsory education was one of the main topics directly addressed (107), excluding those where compulsory education was merely the background context of the research. After removing duplicates across databases and excluding inaccessible articles, the final number of studies considered for analysis was 83.

Following an in-depth reading by the research team, the articles were entered into a documentation matrix. This matrix identified key variables such as year of publication, year of the study, country of reference, methodology, research approach, and language of publication. In addition, it included information relevant to addressing the research question, such as the conceptualization of the expansion of compulsory education, associated variables, and its educational, sociopolitical, economic, and personal implications.

Finally, the data obtained and recorded in the matrix were subjected to both descriptive quantitative analysis and qualitative open coding. In the latter case, and in line with the research objective, the four most relevant dimensions of the impact of compulsory education—educational, sociopolitical, economic, and personal—were used to guide the creation of emerging categories in the analysis process. Both the data collection and the analysis phases were reviewed by at least one additional member of the research team to ensure triangulation.

Results

Descriptive analysis of substantive variables

To understand the distribution and characteristics of the studies analyzed, a descriptive analysis was conducted based on several key criteria: the country of origin of the publication, year of publication, study period, methodology employed, research approach, and language of publication.

The country of origin of each publication made it possible to examine the geographical distribution of scientific output and to identify which regions have generated the largest share of research on the topic, thereby highlighting potential geographical biases in the available knowledge (see Table I). The highest concentration of studies was found in the Americas, with Argentina (20) and Brazil (19) accounting for the largest number of articles on educational expansion. As members of MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market), Uruguay and Paraguay also contributed notably, with 8 and 6 articles, respectively. In the United States, 4 articles were identified. In Europe, Spain produced the largest number of studies on educational expansion (13), followed by the United Kingdom (6). In the remaining European countries, between one and three articles were identified, several of them adopting a comparative perspective. Finally, aside from Turkey with five articles and China with two, the frequency in Asia and Africa was limited to a single article per country, many of which were analyzed through comparative approaches.

Table I. Country of origin of publication

| Africa | America | Asia | Europe | ||||

| Egypt | 1 | Argentina | 20 | Turkey | 5 | Germany | 1 |

| Ghana | 1 | Brazil | 19 | China | 2 | Belgium | 1 |

| Benin | 1 | Bolivia | 2 | Thailand | 1 | Denmark | 1 |

| Liberia | 1 | Uruguay | 8 | Afghanistan | 1 | Spain | 13 |

| Tanzania | 1 | Paraguay | 6 | India | 1 | Finland | 1 |

| Zambia | 1 | Chile | 2 | Indonesia | 1 | France | 2 |

| South Africa | 1 | United States | 4 | Cambodia | 1 | Greece | 1 |

| Costa Rica | 1 | Nepal | 1 | Ireland | 1 | ||

| El Salvador | 1 | Vietnam | 1 | Italy | 2 | ||

| Jamaica | 1 | Taiwan | 1 | Norway | 1 | ||

| Netherlands | 1 | ||||||

| Poland | 2 | ||||||

| Portugal | 2 | ||||||

| United Kingdom | 6 | ||||||

| Romania | 2 | ||||||

| Sweden | 3 | ||||||

| Switzerland | 2 | ||||||

Source: Own elaboration

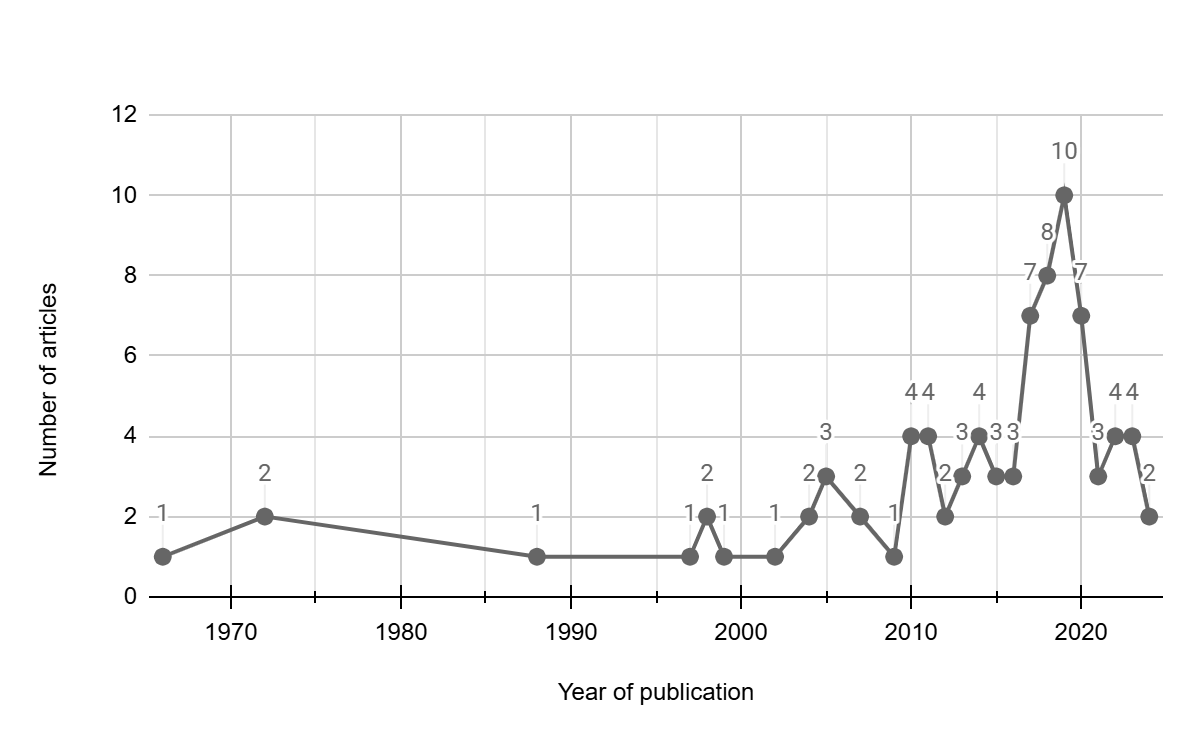

Another key aspect was the year of publication of the reviewed literature, which made it possible to trace the evolution of research over time. Examining the chronology of the studies helped identify trends, developments, and shifts in paradigms, approaches, and methodologies across different periods. As shown in Figure II, the earliest study dates back to 1966; however, it was not until the 2000s that publications on the expansion of education began to appear more consistently. From 2010 onward, there was a marked increase in research on the topic, with 2019 representing the year in which the highest number of publications were recorded.

Figure II. Distribution of articles by year of publication

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Overall, the chronological distribution of publications reflects a growing scholarly interest in educational expansion, particularly in recent decades. However, this evolution has not been uniform, as notable contrasts can be observed in recent years—for instance, only three articles were published in 2016, compared to a peak of ten in 2019. Furthermore, the increase in publication frequency during the final years of the 20th century—95.2% of the articles were published after 1997—can be attributed, among other factors, to the emphasis that governments, international organizations, and researchers have placed on education, competencies, and learning objectives for the 21st century.

To enhance the validity and applicability of the findings, and to identify potential variations in results depending on the temporal context of the studies, we also examined the time span in which data were collected for each article. Studies drawing on earlier data generally focused on historical and theoretical analyses of educational expansion in the previous century, often tracing legislation from 1850 onwards (Alcántara, 2019; Lamelas & Barbeito, 2024; Rauscher, 2014, 2015). From the 1950s onward, however, data collection became more systematic, and educational expansion has since been analyzed from diverse perspectives, employing numerical analyses, comparative studies, and qualitative methodologies to strengthen methodological rigor (Shavit & Westerbeek, 1998; Tabak & Çalik, 2020; Paoletta, 2017; Diniz Júnior, 2020).

With respect to the methodology employed, the studies were classified according to their analytical approach and data collection methods. Among the works analyzed, 34.1% applied quantitative methods, 17.6% qualitative methods, and 12.9% mixed methods. Regarding review studies, 14.2% were theoretical, 12.9% historical, and 8.2% comparative. This categorization allowed for an assessment of methodological diversity and highlighted the ways in which the topic has been examined through different scientific perspectives shaped by each approach and method.

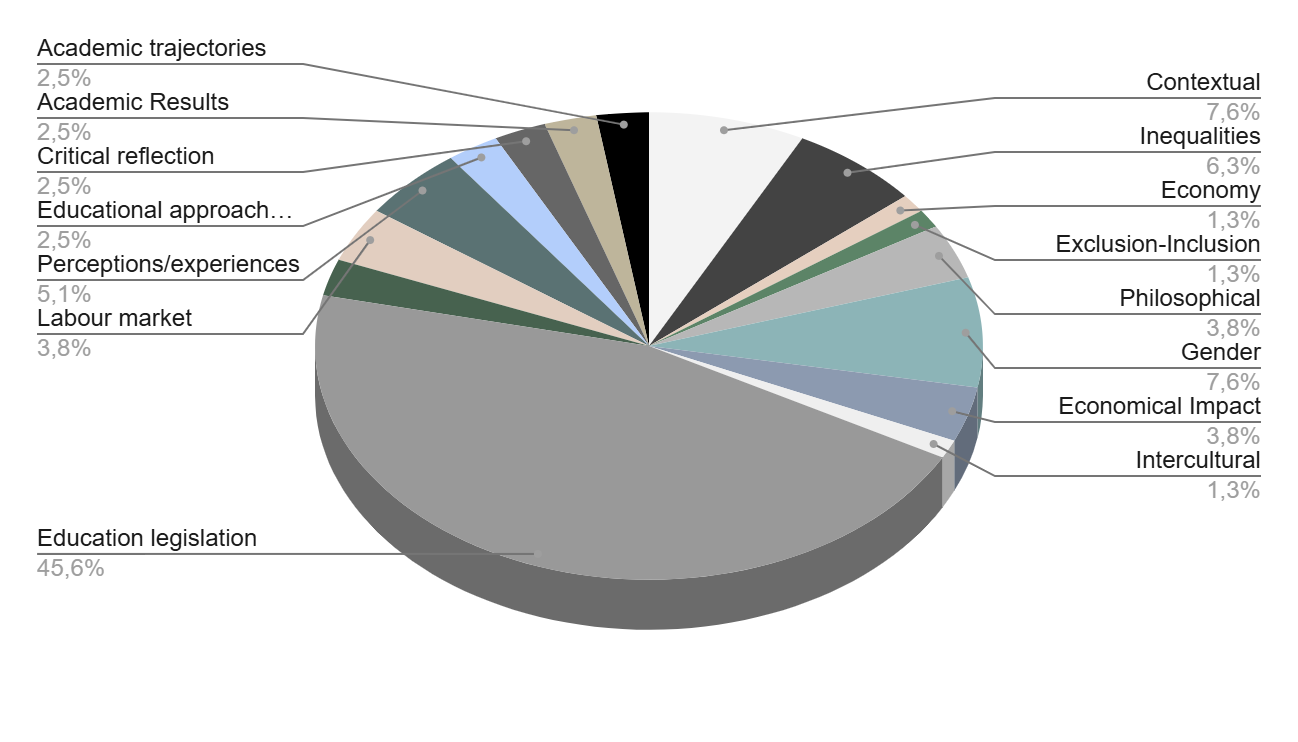

In addition, the research approach was analyzed to identify the theoretical and conceptual perspectives adopted in the studies. This examination made it possible to discern the main schools of thought and interpretive frameworks guiding research on the subject, thereby informing the broader analysis. As shown in Figure III, the most prevalent approach was legislative (45.6%), followed by contextual reviews (7.6%), gender-focused studies (7.5%), and analyses of inequality (6.3%).

Figure III. Main analytical approach of the articles

Source: Own elaboration

Finally, the language of publication was taken into account, as it may influence both access to information and the dissemination of knowledge across academic and policy communities. Among the studies analyzed, 49.4% were published in English, 38.8% in Spanish, and 11.7% in Portuguese.

Thematic-Documentary Analysis

The central theme of this research is the expansion of compulsory education, as reiterated throughout the study. Nevertheless, the articles analyzed do not conceptualize this expansion uniformly, introducing varying interpretations that complicate the categorization of overarching themes. Broadly, the literature addresses expansion in three distinct ways: (1) as an increase in the number of years of schooling, (2) as broader coverage, and (3) as an extension of instructional time.

The increase in years of schooling refers to the extension of the duration of compulsory education. The articles reviewed draw on studies from various countries that explore possibilities such as incorporating early childhood education into compulsory schooling (Cruz, 2017; Lira & Lara, 2022; López, 2019), extending secondary education up to ages 17 or 18 (de Barbieri, 2011; Erten & Keskin, 2019; Gondra, 2010; Krawczyk, 2011; Paoletta, 2017; Terigi, 2013), or, to a lesser extent, including higher education as a compulsory stage (Machin et al., 2012; Murray, 1997).

Coverage refers to the effectiveness of compulsory education—specifically, how many individuals actually gain access to the system and remain enrolled. School dropout, equitable access, the inclusion of previously marginalized groups, and the state’s capacity to enforce compulsory schooling are all factors that affect coverage (Castro & Serra, 2020; Gluz & Rodríguez Moyano, 2018; Nobile, 2016; Ruiz & Schoo, 2014). This explains why the issue is particularly prominent in studies addressing educational expansion in developing countries.

The extension of school hours refers to contexts in which expansion has been pursued not only by increasing the number of schooling years but also by lengthening the school day. This strategy aims to improve learning outcomes and provide a more structured environment (Gondra, 2010; Martino et al., 2023; Misuraca et al., 2022). It is worth noting that these three conceptions may overlap or develop unevenly depending on the political, economic, and social context of each country.

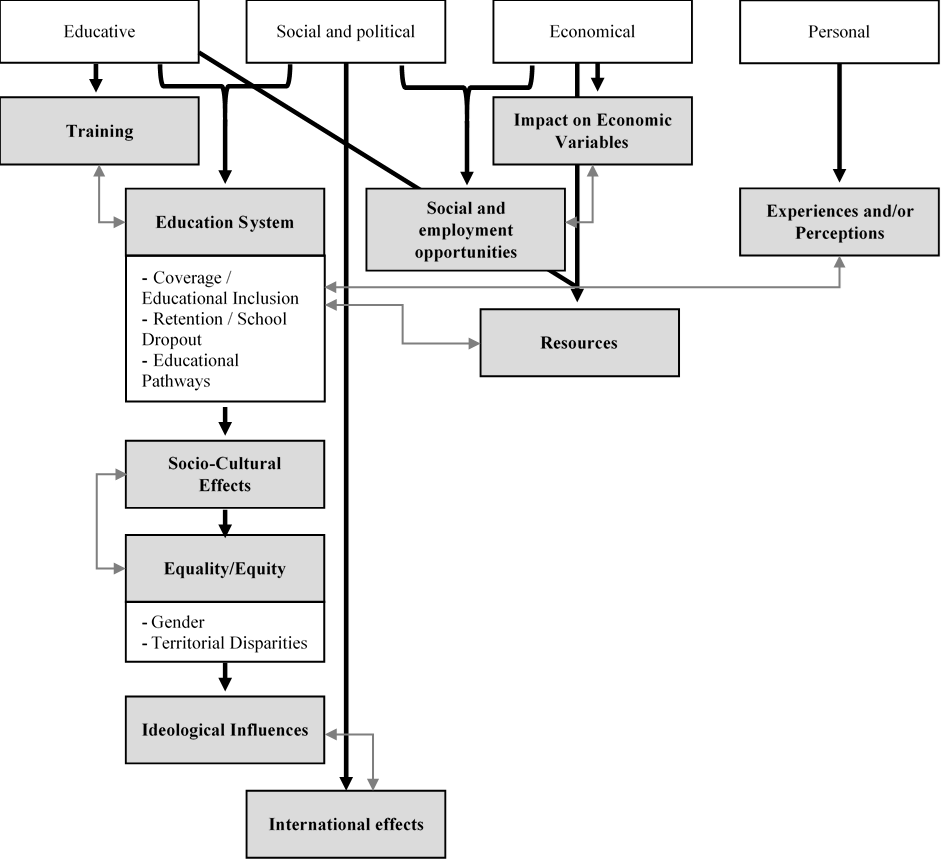

Moreover, the studies reviewed connect the expansion of compulsory education with other themes and variables that are essential to understanding the complexity of the phenomenon. In our analysis, these themes were systematized into distinct categories and subcategories, aligned with the four dimensions of the research. Figure IV specifies these linkages and highlights the most significant relationships among categories.

Figure IV. Dimensions, categories, and subcategories of themes and findings regarding the expansion of compulsory education

Source: Own elaboration

Training

This category encompasses various aspects of the expansion of compulsory education and its effects on both individual development and society at large. The studies analyzed suggest that such expansion creates broader learning opportunities (Misuraca et al., 2022) and supports the construction of a shared knowledge base (Flach, 2009; Hall, 2016; Merino, 2005), thereby fostering more systematic learning and strengthening the overall educational attainment of the population (Luo & Chen, 2018; Machin et al., 2012). In general terms, longer schooling is associated with improvements in students’ general skills (Liwiński, 2020).

One documented effect of expansion is the reduction of illiteracy (Andrés & Esquivel, 2017; Doherty & Male, 1966), although some studies contradict this finding (Mahmoud, 2019). Moreover, compulsory education has been shown to influence early childhood development and growth (Braham, 1972; Cruz, 2017). Nevertheless, some studies warn of the risks of standardization and of early childhood education being reduced to a merely preparatory or care-oriented stage (Lira & Lara, 2022).

The extension of compulsory education has also increased the share of the working-age population holding post-compulsory secondary qualifications (Casquero & Navarro, 2010). It has been associated with improvements in life decision-making (Kırdar et al., 2016) and with stronger economic literacy, reflected in enhanced saving, investment, planning, and market participation capacities. However, the evidence on its impact on financial decision-making remains limited, with some notable exceptions such as improvements in women’s saving habits (Gray et al., 2021).

Regarding its effects on academic performance, improvements have been observed in school grades (Machin et al., 2012) and in reading and writing skills, particularly among men (Mahmoud, 2019). Nonetheless, the impact on standardized test results such as PISA remains ambivalent (Liwiński, 2020; Tabak, 2020). This may be linked to findings suggesting that expansion can also lead to declines in the level, quality, and rigor of education (Cruz, 2007; Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018; Merino, 2005), raising significant challenges in ensuring a robust and equitable education for all students.

Education System

The studies analyzed identify the education system as a central theme, positioning its organization and outcomes as closely linked to the expansion of compulsory education. Several authors underscore this expansion as essential for improving overall system quality and for advancing the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 4 (Giudice & González, 2023). At the same time, persistent challenges remain—including limited resources, insufficient teacher training and qualifications (Braham, 1972; Erten & Keskin, 2019; Flach, 2009), high teacher turnover (Nosei, 2005), low graduation rates, and system fragmentation (Doherty & Male, 1966)—that have yet to be adequately addressed (Acín, 2017). In response to these difficulties, other studies present evidence that updating educational standards (Doherty & Male, 1966) and redefining the role of educators (Hall, 2016) increase the likelihood of successful compulsory education expansion. More specifically, the findings and themes within this category can be grouped into three areas of focus: (1) coverage and educational inclusion, (2) retention and dropout, and (3) educational pathways.

Coverage / Educational Inclusion

In the articles analyzed, coverage is understood as the effective universalization of the right to education (Cruz, 2017). A substantial body of research argues that the expansion of compulsory education enhances system coverage (Djietror, 2011; Nobile, 2016), although its effectiveness depends on being accompanied by complementary pedagogical and social measures (Diniz Júnior, 2020; Rama, 2004; da Silva, 2019). Among these, nutrition (Rengifo, 2019), educational and career guidance (Erten & Keskin, 2019), and attention to students’ individual characteristics (Rengifo, 2019) are particularly emphasized. In the absence of such measures, expansion may risk making the education system more exclusionary (Flach, 2009; Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018), thereby widening gaps in secondary education coverage, especially for minority or historically marginalized populations (Giudice & González, 2023; Juusola, 2023). Conversely, there is evidence that compulsory schooling expansion fosters educational inclusion (de Barbieri, 2011; Djietror et al., 2011), increasing classroom heterogeneity and diversity (Casquero & Navarro, 2010; Erten & Keskin, 2019), while also bringing greater attention to the educational needs of previously unschooled groups (Ruiz et al., 2019).

Retention / School Dropout

Retention refers to the continued presence of students within the education system until they complete a given level of schooling, thereby preventing premature dropout (Erten & Keskin, 2019; Kırdar et al., 2016; Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018; Mussida et al., 2019). The studies analyzed indicate that the extension of compulsory education has significant effects on system retention. According to Mahmoud (2019), an additional year of compulsory schooling increases school enrollment by 0.6 to 0.8 years, although the effect is smaller for females, for whom enrollment rises by only 0.3 to 0.48 years, highlighting a clear gender inequality. This extension also contributes to higher youth employment (Juusola, 2023; Terigi et al., 2013), elevated enrollment rates (Giudice & González, 2023; Negură, 2020), and increased attendance at vocational or professional schools (Erten & Keskin, 2019). These developments directly impact the prevention of early school dropout and promote greater equality in school attendance across social classes and ethnic groups (Rauscher, 2014). Nevertheless, some evidence suggests that compulsory schooling expansion can be associated with higher dropout rates (Hall, 2016; Negură, 2020), particularly in rural areas (Wu, 2010).

Educational Pathways

Regarding educational pathways, the reviewed studies suggest that extending compulsory education helps prevent premature tracking (Merino, 2005). Simultaneously, it promotes greater diversity in school trajectories (Briscioli, 2017) and fosters educational mobility, particularly among urban populations (Wu & Marois, 2024). However, some evidence indicates that expansion may constrain the diversity of pathways (Juusola, 2023) or reduce them to the replication of existing socioeconomic patterns based on students’ social and economic backgrounds (Valdés, 2022). In any case, the extension of compulsory education has stimulated the creation of vocational and professional schools across various educational levels (Doherty & Male, 1966). Indeed, many students who entered the education system following the reform opted to continue their studies in vocational rather than academic institutions (Erten & Keskin, 2019). Despite this, the expansion has enhanced access to higher education (Hall, 2016; Wu, 2010), although its impact on equity within the university system remains limited. Finally, this diversification of educational pathways faces substantial constraints, particularly due to insufficient resources to adequately address student heterogeneity and their diverse educational trajectories (Briscioli, 2017).

Socio-Cultural Effects

The studies analyzed report numerous socio-cultural effects. From a social perspective, the expansion of compulsory education is considered an appropriate response in societies characterized by poverty (Oreja Cerruti, 2023), as it has been identified as a factor that promotes social integration and cohesion (Merino, 2005). This is reflected in improvements in safety and social well-being, as several studies indicate that compulsory education reduces crime and delinquency (Erten & Keskin, 2019; Gray et al., 2021; Machin et al., 2012).

Reductions in risk behaviors, such as teenage pregnancy, have also been observed (Gray et al., 2021). However, the relationship between education and early motherhood is not conclusive. Some studies suggest that educational expansion does not directly reduce adolescent pregnancy (James & Vujić, 2018; Kırdar et al., 2016) but rather contributes to delaying the birth of the first child (Ní Bhrolcháin & Beaujouan, 2012). Evidence indicates that this shift in fertility timing is primarily driven by macroeconomic and structural factors rather than cultural transformations (Ní Bhrolcháin & Beaujouan, 2012).

Another notable social effect is the delay in youth emancipation, resulting both from the prolongation of schooling and from the economic conditions associated with remaining in the education system (Miret, 2004). Concurrently, the social value of educational credentials has declined, particularly in the case of the secondary school diploma, which has lost some of its significance as a labor market credential, especially for women in urban settings (Kırdar et al., 2016).

From a cultural perspective—and although socioeconomic and familial factors continue to play a substantial role (Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010)—one of the main effects observed is an increase in cultural capital at both the individual and family levels (Braham, 1972; Petrongolo, 1999), as well as its contribution to strengthening democratic participation (Gray et al., 2021).

Equality/Equity

From the perspective of equality, the studies analyzed highlight that the expansion of compulsory education contributes to sociocultural equality (Lamelas & Barbeito, 2024; Luo & Chen, 2018) by reducing inequalities (Diniz Júnior, 2020; Misuraca et al., 2022; Murtin & Viarengo, 2011), particularly in the educational domain (Juusola, 2024; Nobile, 2016). However, they also caution that when coverage is not universal, it can generate new forms of inequality (Meschi & Scervini, 2014). While its role in promoting equal educational and social opportunities (de Barbieri, 2011; Doherty & Male, 1966; Flach, 2009; Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018; Merino, 2005; Tabak & Çalık, 2020; Wu & Marois, 2024) is widely recognized, some studies question its effectiveness, arguing that it does not guarantee equitable access in socioeconomic terms (Wu, 2010). In this regard, they emphasize that the equitable distribution of educational opportunities is more decisive than the mere existence of compulsory schooling. This is reflected in the persistence of inequalities in grade repetition, dropout, and over-age enrollment—particularly among youth from lower-income sectors—despite expanded access (Nobile, 2016). Furthermore, no clear relationship has been established between the expansion of compulsory education and the reduction of social inequality in access to higher education (Shavit & Westerbeek, 1998). Finally, the findings and themes within this category can be grouped into two areas of interest: (1) gender and (2) territorial disparities.

Gender

Regarding gender, multiple studies indicate that the expansion of compulsory education can play a significant role in promoting equality (Kırdar et al., 2016; Miret, 2004; Wu & Marois, 2024), both socially and in the labor market (Mussida et al., 2019). This effect is explained by the capacity of extended schooling to broaden educational opportunities for women—who have historically faced greater barriers to accessing the education system (Luo & Chen, 2018)—and by its function as a compensatory mechanism against sociocultural norms and practices that have limited female participation in certain contexts, particularly in rural or traditionalist settings (Erten & Keskin, 2019). Several authors argue that such policies help reduce structural and symbolic barriers, producing positive impacts on women’s social inclusion and labor market participation (Kırdar et al., 2016; Miret, 2004; Wu & Marois, 2024; Mussida et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, this optimistic perspective must be tempered in light of evidence showing that the expansion of compulsory education does not operate in a gender-neutral manner and may even produce unintended or contradictory effects. For instance, some studies suggest that, rather than closing gaps, educational expansion in certain contexts may reinforce existing inequalities, particularly when not accompanied by active inclusion and support measures (Mahmoud, 2019). Specifically, school dropout rates remain substantially higher among boys, raising questions about the differential effects of compulsory schooling by gender (Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010). This pattern indicates that persistence in the education system depends not only on access but also on the material, motivational, and cultural conditions that differently influence men and women.

Territorial Disparities

With respect to territorial disparities, the evidence is ambivalent. Some studies suggest that the expansion of compulsory education has exacerbated inequalities between rural and urban areas, as well as across jurisdictions, due to the uneven distribution of resources and the structural limitations of disadvantaged regions (de Barbieri, 2011; Doherty & Male, 1966; Wu, 2010). In contrast, other research indicates that, when coupled with targeted support policies, this measure can promote territorial equity and improve educational access in rural contexts (Kırdar et al., 2016). Additionally, some studies link these two dimensions by noting that the expansion of compulsory education may increase gender disparities in school attendance within rural settings (Negură, 2020). Paradoxically, however, it has also been observed that such expansion can help reduce educational disparities across geographical areas, particularly benefiting women in rural regions (Kırdar et al., 2016).

Ideological Influences

The category of ideological influences encompasses aspects related both to the ideals that justify the expansion of compulsory education and to the transformations it produces in civic mentality. The studies analyzed indicate that extending compulsory education is associated with societal progress and modernization (Alcántara, 2019; Andrés & Esquivel, 2017; Rengifo Streeter, 2019), reinforces nation-building (Andrés & Esquivel, 2017; Jones et al., 1998; Negură, 2020), and shapes citizenship (Flach, 2009; Rama, 2004) by enhancing political and ideological awareness among the general populace (Braham, 1972) and youth in particular (Luo & Chen, 2018). Furthermore, by highlighting the societal importance of education (Diniz Júnior, 2020; Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018), it supports the recognition of education as both a right and a social achievement (Acín, 2017; Cruz, 2017; Krawczyk, 2011; Oreja Cerruti, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2019; Ruiz & Scioscioli, 2018), contributes to debates regarding the public and free nature of education (Lamelas & Barbeito, 2024), and acts as a counterbalance to the influence of churches, sects, and other private entities in the sector (Andrés & Esquivel, 2017). Nonetheless, some studies reveal a lack of consensus regarding its actual necessity (de Barbieri, 2011), as well as its potential role as an instrument of social reproduction (Wu, 2010).

Social and employment opportunities

Many of the articles analyzed address, either partially or fully, the social and labor opportunities generated by the expansion of compulsory education, viewing it as a strategic investment in social, economic, political, and human development (Diniz Júnior, 2020). Although evidence regarding its impact on the expansion of human capital is mixed (Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010; de Barbieri, 2011; Erten & Keskin, 2019; Wu & Marois, 2024), studies consistently indicate that extended schooling reduces the risk of unemployment (Gray et al., 2021; Mussida et al., 2019), enhances social and labor inclusion (Acín, 2017; Jones et al., 1998; Juusola, 2023)—including for adolescents (Abiétar-López et al., 2017)—increases productivity (Machin et al., 2012), and fosters employability by facilitating adaptation to labor market demands (Hall, 2016; Murray, 1997; Paoletta, 2017; Wu, 2010) as well as improving workforce qualifications (Ruiz et al., 2019). These effects, in turn, influence quality of life (Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010; Diniz Júnior, 2020), promote social mobility (Wu, 2010; Wu & Marois, 2024)—including intergenerational mobility (Betthäuser, 2017; Rama, 2004)—and contribute both to higher income (Gray et al., 2021; Kırdar et al., 2016) and to reducing income inequality (Mussida et al., 2019), particularly in rural areas (Strawiński & Broniatowska, 2021). Nonetheless, consensus has yet to be reached on whether compulsory schooling reduces unemployment in recessionary contexts (Hall, 2016) or directly influences labor market outcomes (Mahmoud, 2019).

Despite these positive effects, the articles also highlight potential negative consequences, including limited improvements in individuals’ economic situations, the risk of credential inflation without corresponding labor market gains (Rauscher, 2015), overqualification (Jones et al., 1998), higher unemployment among the most educated, loss of early work experience (Erten & Keskin, 2019; Hall, 2016), and a mismatch between compulsory schooling and actual economic needs (Braham, 1972). Additionally, the inability to work while studying (Juusola, 2023) may exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities, perpetuating the influence of family economic status on children’s opportunities (Wu, 2010).

International Effects

Some of the effects identified in the analyzed articles pertain to politics and international relations. Several studies note that the expansion of compulsory education not only fosters alliances (Giudice & González, 2023) and highlights asymmetries between nations, but also brings certain developing countries into legislative and geopolitical alignment with the West—particularly Europe—by adapting their national legislation to the guidelines of international organizations (Diniz Júnior, 2020) and aligning with European educational policies and objectives (Braham, 1972; Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010).

Impact on Economic Variables

One aspect emphasized by the analyzed studies is the impact of expanding compulsory education on countries’ economic variables. Numerous articles argue that such expansion drives economic development (Murtin & Viarengo, 2011; Rauscher, 2015; Wu, 2010)—although some studies report no statistical correlation between increased compulsory schooling and economic growth (Holmes, 2013)—fosters the modernization and industrialization of the economy (Braham, 1972), promotes innovation (Rauscher, 2015), and supports the creation of higher-quality employment opportunities (Shavit & Westerbeek, 1998). Furthermore, there is evidence that extending education generates high rates of return on investment, particularly at lower educational levels (Nitungkorn, 1988).

Resources

As expected, the increase in the years of compulsory schooling has a significant impact on resources, both within the educational system and at the national level. It is therefore unsurprising that a substantial number of studies examine the individual and collective costs associated with this measure. Some of the analyzed articles argue that expanding compulsory education raises the marginal cost of schooling (Murtin & Viarengo, 2011), increases opportunity costs (Jones et al., 1998; Murray, 1997), and elevates implementation expenses (Erten & Keskin, 2019). Consequently, some authors question whether these high costs are justified by the outcomes achieved (Mancebo & Zorrilla, 2018). Conversely, others contend that expansion leads to a more efficient use of invested resources (Kırdar et al., 2016), although they caution that it may exacerbate the unequal distribution of resources (Alcántara, 2019) and amplify deficiencies in infrastructure and educational materials (Braham, 1972; Nitungkorn, 1988). Additionally, there is a risk that it imposes an extra financial burden on families (Jones et al., 1998), who may be required to contribute to the system’s viability through tuition and other fees (Wu, 2010), though this effect appears to diminish over time, likely as a result of scholarship policies (Petrongolo, 1999). Finally, some studies note that expansion may facilitate public–private collaboration in education and, ultimately, serve as a pathway toward the covert privatization of schooling (Diniz Júnior, 2020).

Experiencies and/or perceptions

Any change in social structures affects the subjectivity of the individuals within them. Under the category of experiences and perceptions, the analyzed articles identify various personal effects associated with the expansion of compulsory education. Notably, some individuals report a sense of self-improvement and personal projection (Paoletta, 2017), as well as engagement in practices that reinforce their perception of success when achieving strong academic performance (Casquero Tomás & Navarro Gómez, 2010). Several studies also indicate that adolescents recognize the importance of continuing their education to enhance their employment prospects (Abiétar-López et al., 2017), although in some cases they develop unrealistic expectations regarding their future, influenced by the longer period of compulsory schooling (Jones et al., 1998). In addition to these positive effects, negative experiences are also reported, including fatigue and lack of motivation, feelings of irrelevance, the undervaluing of alternative educational pathways (Murray, 1997), and resistance to compulsory schooling (Paoletta, 2017), which may diminish perceived well-being by restricting a sense of autonomy (Kırdar et al., 2016). Finally, the expansion of compulsory education is noted to potentially increase feelings of alienation among rural populations (Negură, 2020).

Discussion and Conclusions

The results presented underscore the diversity of conceptions surrounding the expansion of compulsory education, as well as the complexity and the multiplicity of factors with which it is interwoven. From both historical and contemporary perspectives, this process appears characterized by persistent tensions between the objectives of the state’s nation-building project and the socioeconomic and cultural conditions that shape its implementation. In this regard, although schooling is generally perceived as a marker of progress, it remains an ambivalent phenomenon: for some, it constitutes a disciplinary imposition; for others, a means of accumulating “human capital” aimed at economic productivity; and for still others, a pathway to knowledge that counters ignorance and irrationality (Gimeno, 2000).

This ambivalence is particularly pronounced when contrasting the priorities of countries that have achieved high levels of educational coverage with those that continue to face challenges in ensuring the genuine universality of their educational systems (Ruiz & Schoo, 2014). In the latter, the expansion of compulsory education remains primarily focused on increasing access, whereas in the former, debates center on issues such as extending schooling beyond basic levels, enhancing the quality of education provided, and addressing persistent inequalities in terms of equity and opportunity (Pires & Brutten, 2007). Accordingly, while international discourse often emphasizes the need to prolong the period of compulsory schooling (Akboga, 2015), in many developing countries the priority continues to be ensuring that primary and secondary education are genuinely accessible to the entire population, as the fulfillment of the right to education depends largely on this (Moreno Olmedilla, 2005).

However, coverage represents only one of the multiple dimensions implicated in the global expansion of compulsory education (Castro & Serra, 2020). As the analyzed articles indicate, this phenomenon must be understood in relation to its effects on the structure and organization of the education system, on the transformation of social expectations regarding citizenship, on the evolution of the labor market, and on the reconfiguration of individuals’ life trajectories (Woodin et al., 2013). In this regard, examining the educational, sociopolitical, economic, and personal implications of compulsory education expansion—implications that constitute both the guiding question and the rationale of this study—is essential for understanding the scope and limits of this transformation across diverse contexts. Therefore each of these dimensions is explored in greater detail below, with the aim of providing a comprehensive perspective on the challenges and contradictions that characterize this process.

From an educational perspective, the analysis indicates that the expansion of compulsory education has undeniable formative effects on both individuals and the broader school community. These effects manifest as improvements in students’ knowledge, skills, values, and behaviors (Miralles Romero & Castejón Costa, 2009). However, research shows that such improvements do not always materialize, whether due to school dropout, limited coverage, poor academic outcomes, or other factors that constrain the actual impact of schooling. Consequently, rather than focusing solely on policies and legislation, it is essential to reflect on the effective implementation of compulsory education across different school contexts. This entails addressing students’ needs, providing appropriate guidance and support, and ensuring that compulsory schooling translates into genuine educational opportunities rather than merely extending the system without guaranteeing its effectiveness. In this regard, it is crucial to consider the pedagogical purposes of the years in which compulsory education is extended, to examine both the aims and the methods of this process, and to ensure that its expansion adheres to criteria of quality and equity beyond mere coverage. Achieving this requires revisiting school content, instructional methods, and organizational structures, thereby avoiding a retention-focused approach devoid of genuine pedagogical transformation.

From a sociopolitical perspective, the close relationship between education and the social and political life of individuals is undeniable (Dewey, 2004). The expansion of education, beyond transforming the school environment, impacts factors such as equality, inclusion, social mobility, quality of life, and disparities in opportunities linked to gender or place of origin. However, research—whether empirical, theoretical, or historical—demonstrates that these effects are neither uniform nor linear. Findings often yield contradictory conclusions, even within the same population, highlighting the complexity of the phenomenon and the difficulty of making categorical claims regarding its impact. It is therefore essential to consider the specificities of each community, avoiding the assumption that education produces homogeneous effects across contexts. At the same time, it must be acknowledged that education alone does not guarantee social or political success (Tarabini, 2020). While it represents a step in the right direction, the expansion of compulsory education must be accompanied by policies that foster equality of opportunity, labor market integration, and access to culture, among other dimensions. Only through coherent and coordinated strategies can meaningful improvements in individuals’ sociopolitical sphere be realized.

As demonstrated, the expansion of compulsory education also carries significant economic implications. On one hand, it contributes to economic development and modernization, primarily by enhancing individual productivity, thereby facilitating access to better employment opportunities and reducing income inequality. On the other hand, it entails a substantial increase in the costs of the education system (Rauscher, 2014), prompting debates regarding the return on investment and the efficiency of resource allocation, while also fostering public–private partnerships or, in some cases, covert privatization of education (Ball & Youdell, 2007). Given this dual effect, it is evident that the economic dimensions of expanding compulsory education require careful examination, considering both its benefits and its associated costs and risks. Striking a balance between educational investment, the outcomes achieved, and the financial sustainability of the system is therefore essential to ensure that the growth of schooling translates into tangible improvements in social well-being and long-term economic development.

The expansion of compulsory education also exerts a significant impact on the personal dimension. These effects, which arise from how individuals perceive and experience their integration into an expanding education system, are positive for those who regard the system as a challenge to overcome, an opportunity to enhance their career prospects, or a reinforcement of academic success already attained (Gimeno, 2013). This perspective is particularly pronounced in developing countries, where confidence in education as a pathway to social and economic advancement remains strong. Conversely, negative effects are also evident, including fatigue, lack of motivation, feelings of irrelevance or alienation, and rejection of compulsory schooling. Such experiences correspond with critiques of the education system that characterize it as producing alienating relationships, wherein power is exercised over individuals at the expense of their freedom and autonomy (Laval, 2004). Both perspectives—the one emphasizing the benefits of educational expansion and the one highlighting its adverse effects—reflect the ongoing debate concerning the purposes of schooling: should it innovate and adapt to contemporary conditions, or maintain certain principles to uphold a shared culture? (Quintana, 1988). This ambivalence indicates that any policy aimed at expanding compulsory education must consider these subjective effects, since, however commendable the economic, sociopolitical, or formative objectives may be, the success of such expansion ultimately hinges on the meaning it holds and the degree of acceptance by those directly affected (López, 2007).

As the document analysis demonstrates, the expansion of compulsory education is a multidimensional phenomenon whose effectiveness is closely linked to the educational, sociopolitical, economic, and personal contexts in which it is implemented. Thus, although extending compulsory schooling may present an opportunity to guarantee the right to education, expansion alone does not necessarily lead to improvements in educational quality or equity. Its impact depends on how the additional time is implemented and utilized, which means that structural challenges—such as inequality, exclusion, and school dropout—may persist or even intensify, particularly when pedagogical conditions and system resources are not aligned with students’ needs.

For compulsory education to serve as a genuine tool for equity, it is essential to adopt pedagogical strategies that address students’ heterogeneity and maximize their formative potential. Adapting teaching processes, implementing multiple instructional strategies, and allocating resources in a differentiated manner are crucial to providing greater support for students from more disadvantaged backgrounds, with the aim of achieving equitable learning outcomes (Alcántara, 2019). Accordingly, the extension of compulsory education should not be regarded as an end in itself but as a starting point for the development of more inclusive and equitable educational systems. Far from supposing “another brick in the wall”—to borrow Pink Floyd’s famous metaphor—the expansion of compulsory education should represent a genuine opportunity for growth and development for all students, albeit experienced in diverse ways.

Finally, despite the scope of this analysis, the review has certain notable limitations that must be acknowledged, stemming precisely from the nature of the studies available. In particular, it does not explore in depth the contextual specificities of different countries, which may constrain understanding of how historical, cultural, and institutional factors shape both the implementation and outcomes of educational expansion. Similarly, due to the limited literature, the perspectives of teachers and students are scarcely represented, restricting access to relevant subjective insights. Moreover, although territorial and gender inequalities are recognized, no intersectional approach is employed that would allow examination of other significant variables, such as religion or ethnic origin. Finally, while the tension between public and private financing is noted, the economic and financial mechanisms underlying the sustainability and long-term impact of educational policies are not explored in detail. These limitations, however, suggest promising avenues for future research, including studies on the effects of expansion on teachers’ trajectories and practices, the role of educational technologies in school expansion policies, and longitudinal investigations assessing the impact of reforms across generations and diverse geographical contexts. Such work could enrich the academic debate while also critically addressing the pedagogical purposes of schooling, its significance, and the ways in which is implemented in terms of quality and equity.

References

Abiétar-López, M., Navas-Saurin, A. A., Marhuenda-Fluixá, F. y

Salvà-Mut, F. (2017). La construcción de subjetividades en itinerarios

de fracaso escolar. Itinerarios de inserción sociolaboral para

adolescentes en riesgo.

Acín, A. (2017). Aspectos organizativos de la educación secundaria de

adultos en Córdoba y en Cataluña: un análisis comparado.

Akboga, S. (2015). The expansion of compulsory education in Turkey:

local and world culture dynamics.

Alcantara, W. R. (2019). Compulsory school and investment in public

education: A historical perspective (São Paulo, 1874-1908).

Andrés, Y. P. y Esquivel, R. M. (2017). Educación escolar y

masonería: krausismo y laicidad entre España y Costa Rica a finales del

siglo XIX.

Ball, S. y Youdell, D. (2007).

Bernal, A. y Martín, J. P. (2001). La dialéctica saber/poder en

Michel Foucault: Un instrumento de reflexión crítica sobre la escuela.

Betthäuser, B. (2017). Fostering Equality of Opportunity? Compulsory

Schooling Reform and Social Mobility in Germany.

Braham, R. L. (1972).

Briscioli, B. (2017). Aportes para la construcción conceptual de las

“trayectorias escolares”.

Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N. y Strohl, J. (2013). Recovery: Job growth

and education requirements through 2020.

Casquero Tomás, A. y Navarro Gómez, M. L. (2010). Determinantes del

abandono escolar temprano en España: un análisis por género.

Castro, A., y Serra, M. F. (2020). Espacio escolar y utopía

universalizadora: Definiciones, tensiones y preguntas en torno a lo

espacial y la ampliación del derecho a la escolaridad.

Consejo Escolar de Estado. (2023). Informe 2023 sobre el estado del

sistema educativo. Curso 2021-2022. Ministerio de Educación, Formación

Profesional y Deportes.

Cruz, M. N. D. (2017). Early childhood education and extension of

compulsory schooling: repercussions for the cultural development of the

child.

Dale, N. (12 de marzo de 2025). El Departamento de Educación despide

a la mitad de su plantilla, la alternativa a la promesa de Trump de

liquidar la agencia.

da Silva, M. (2019). Expansion of compulsory schooling in Brazil:

what happened to secondary education?.

De Barbieri, L. M. (2011). Educación y escuela en el año del

bicentenario de Argentina historia reciente: Tucumán 1990/2010.

Dewey, J. (2004).

Diniz Júnior, C. A. (2020). Obrigatoriedade e gratuidade da educação

nos Estados Parte do Mercosul.

Djietror, B. B. K., Okai, E. y Kwapong, O. A. T. F. (2011). Promoting

Inclusive Education in Ghana.

Doherty, E. M. y Male, G. A. (1966).

Egido, I. (2013). Presentación: la educación infantil en perspectiva

europea.

Erten, B. y Keskin, P. (2019). Compulsory schooling for whom? The

role of gender, poverty, and religiosity.

Flach, S. D. F. (2009). The right to education and its relationship

with the enlargement of schooling in Brazil.

Gimeno, J. (2000).

Gimeno, J. (2012). La educación obligatoria: Una escolaridad igual

para sujetos diferentes en una escuela común. En José Gimeno, Rafael

Feito, Philipe Perrenoud, y María Clemente (Comp.),

Gimeno, J. (2013).

Giudice, J. y González, I. (2023). Educación superior en la región:

heterogeneidades, desafíos y transformaciones.

Gluz, N. y Rodríguez Moyano, I. (2018). Obligatoriness challenged:

Who leaves whom? School’s exclusion of young people in vulnerable

conditions. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 162.

Gondra, J. G. (2010). ¿ Gobierno de los otros? Expansión del tiempo

escolar y obligatoriedad de la enseñanza en Brasil.

Gray, D., Montagnoli, A. y Moro, M. (2021). Does education improve

financial behaviors? Quasi-experimental evidence from Britain.

Hall, C. (2016). Does more general education reduce the risk of

future unemployment? Evidence from an expansion of vocational upper

secondary education.

Holmes, C. (2013). Has the Expansion of Higher Education Led to

Greater Economic Growth?

James, J. y Vujić, S. (2018). From High School to the High Chair:

Education and Fertility Timing.

Jones, G. W., Nagib, L., Sumono y Handayani, T. (1998). The expansion

of high school education in poor regions: The case of East Nusa

Tenggara, Indonesia.

Juusola, H. (2023). What do young people think about the extension of

compulsory education?.

Kırdar, M. G., Dayıoğlu, M. y Koc, I. (2016). Does longer compulsory

education equalize schooling by gender and rural/urban residence?.

Krawczyk, N. (2011). Some contemporary challenges of secondary

education in Brazil.

Lamelas, G. A. y Barbeito, I. G. (2024). A 140 años de la sanción de

la Ley 1420: conmemorar, rememorar y recrear sentidos en el horizonte de

lo común.

Laval, C. (2004).

Liwiński, J. (2020). The impact of compulsory schooling on Hourly

Wage: evidence from the 1999 education reform in Poland.

López, N. (2005).

López, O. S. (2019). In the interest of the public good: Texas

pre-kindergarten compulsory law. Contemporary

Luo, Y. H. y Chen, K. H. (2018). Education expansion and its effects

on gender gaps in educational attainment and political knowledge in

Taiwan from 1992 to 2012.

Machin, S., Vujić, S. y Marie, O. (2012). Youth crime and education

expansion

Mahmoud A. A. (2019). Keeping Kids in School: The Long-Term Effects

of Extending Compulsory Education. Education Finance and Policy, 14(2):

242–271.

Mancebo, M. E. y Zorrilla, J. P. (2018). “Del dicho al hecho hay un

gran trecho”: Obstáculos para la expansión de la escolaridad media en

Uruguay

Marín, A. (22 de enero de 2024). Educación obligatoria hasta los 18:

ventajas e inconvenientes de su implantación.

Merino, R. (2005). De la LOGSE a la LOCE. Discursos y estrategias de

alumnos y profesores ante la reforma educativa.

Merino, R. (2005). De la LOGSE a la LOCE. Discursos y estrategias de

alumnos y profesores ante la reforma educativa.

Miralles Romero, M.J. y Castejón Costa, J.L. (2009). Los efectos de

la escuela en los contextos educativos y sus aplicaciones metodológicas.

Miret, P. (2004). ¿Qué relación tiene el aumento en los años de

escolaridad no obligatoria en la emancipación de los jóvenes en Cataluña

durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX?.

Misuraca, M. R., Szilak, S., Barrera, K. A. y Ghelfi, F. D. (2022).

La Jornada extendida en la educación secundaria bonaerense. Condiciones

y necesidades.

Moreno Olmedilla, J. M. (2005). Secondary Education in Afghanistán: a

portray of post-conflict education reconstruction.

Murray, Å. (1997). Young people without an upper secondary education

in Sweden. Their home background, school and labour market experiences.

Murtin, F. y Viarengo, M. (2011). The expansion and convergence of

compulsory schooling in Western Europe, 1950–2000

Mussida, C., Sciulli, D. y Signorelli, M. (2019). Secondary school

dropout and work outcomes in ten developing countries.

Negură, P. (2020). Compulsory primary education and state building in

rural Bessarabia (1918–1940).

Ní Bhrolcháin, M. y Beaujouan, É. (2012). Fertility postponement is

largely due to rising educational enrolment.

Nitungkorn, S. (1988). The problems of secondary education expansion

in Thailand. Japanese

Nobile, M. (2016). La escuela secundaria obligatoria en Argentina:

Desafíos pendientes para la integración de todos los jóvenes.

OECD (2012),

OECD (2022).

Oreja Cerruti, M. (2023). Las trayectorias como principio

estructurante de las políticas para la escuela secundaria en Argentina:

un análisis crítico de las orientaciones gubernamentales.

Paglayan, A. S. (2022). Education or indoctrination? The violent

origins of public school systems in an era of state-building.

Paoletta, H. (2017). ¿Es obligatoria la educación secundaria para los

jóvenes y adultos?: sentidos acerca de la obligatoriedad escolar

presente en Centros Educativos de Nivel Secundario

Petrongolo, B. (1999). ¿Incentiva el paro juvenil la escolarización

secundaria?. Ekonomiaz:

Pires, J. y Brutten Baldi, E. M. (2007). La enseñanza media y la

enseñanza técnica en el contexto de la reforma de la educación básica

brasileña.

Quintana, J.M. (1988).

Rama, G. W. (2004). La evolución de la educación secundaria en

Uruguay

Rauscher, E. (2014). Hidden gains: Effects of early U.S. Compulsory

schooling laws on attendance and attainment by social background.

Rauscher, E. (2015). Educational expansion and occupational change:

US compulsory schooling laws and the occupational structure 1850–1930.

Rengifo Streeter, F. (2019). La crisis educativa chilena.

Escolarización y política social, 1930-1960.

Ruiz, G. R. y Scioscioli, S. (2018). El derecho a la educación:

dificultades en las definiciones normativas y de contenido en la

legislación argentina.

Ruiz, G., Scioscioli, S. y Rodríguez, M. L. (2019). La educación

secundaria en cinco países de América del Sur: definiciones normativas y

alcances empíricos desde la perspectiva del derecho a la educación.

Ruiz, M. C. y Schoo, S. (2014). La obligatoriedad de la educación

secundaria en América Latina. Convergencias y divergencias en cinco

países.

Sevilla, D. (2007). La Ley Moyano y el desarrollo de la educación en

España.

Shavit, Y. y Westerbeek, K. (1998). Educational stratification in

Italy: Reforms, expansion, and equality of opportunity.

Silva, M. (2018). The school geography in the context of high

school’s reform: an analysis to besides the place.

Strawiński, P. y Broniatowska, P. (2021). The impact of prolonging

compulsory general education on the labour market.

Tabak, H. y Çalık, T. (2020). Evaluation of an educational reform in

the context of equal opportunities in Turkey: Policy recommendations

with evidence from PISA. International Journal of Contemporary

Tarabini, A. y Bonal, X. (2016).

Tarabini, A. (2020). ¿Para qué sirve la escuela? Reflexiones

sociológicas en tiempos de pandemia global.

Terigi, F., Briscioli, B., Scavino, C., Morrone, A. y Toscano, A. G.

(2013). La educación secundaria obligatoria en la Argentina: entre la

expansión del modelo tradicional y las alternativas de baja escala.

Valdés, M.T. (2022). Horizontal inequality in the transition to upper

secondary education in Spain.

Verger, A., Altinyelken, H. K. y Novelli, M. (Eds.). (2018).

Woodin, T., McCulloch, G. y Cowan, S. (2013). Raising the

participation age in historical perspective: policy learning from the

past?

Wu, J. y Marois, G. (2024). Education Policies and Intergenerational

Educational Mobility in China: New Evidence for the 1986–95 Birth

Cohort.

Wu, X. (2010). Economic transition, school expansion and educational

inequality in China, 1990–2000.