The Leadership of Schools in Spain. Analysis of Regulations and Evidence

La dirección de los centros educativos en España. Análisis normativos y evidencias

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-410-710

Francisco López Rupérez

Director of the Extraordinary Chair of Educational Policies of the UCJC

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-9652

Abstract

The main purpose of this study is to analyse the evolution of the Spanish regulatory framework between 1970 and 2020, about the professionalisation of managerial roles, and to draw some conclusions concerning policies focused on school leadership. The introduction outlines the special consideration given internationally to school leadership and its role in student outcomes and school improvement. The importance of the professionalisation of managerial roles is then considered to establish the conceptual framework. This is followed by a comparative analysis of the various education laws enacted in Spain during this period. To ensure a consistent comparison, a uniform analytical framework has been employed, inspired by international practices and comprising three criteria and eight sub-criteria related to professionalisation. Empirical evidence is then examined in relation to the case of the Autonomous Community of Navarre and its anomaly concerning the professionalisation of school leadership. The discussion of both types of results highlights the weaknesses of the Spanish model. The most innovative approaches to the professionalisation of school leadership are found in the LOPEGCE and the LOCE. The study concludes with several recommendations for the future of school leadership in Spain, including the pursuit of a clear and balanced school leadership model, inspired by the modern concept of a profession and aligned with international consensus on the complexity and challenges of school leadership and its implications; the incorporation of available empirical evidence; and the recognition of progress made in other developed countries towards the increasing professionalisation of managerial roles.

Keywords:

Leadership, Educational establishments, Educational legislation, Educational policy, Educational management

Resumen

El presente trabajo tiene como finalidad principal analizar la evolución del marco normativo español entre 1970 y 2020, en lo concerniente a la profesionalización de la función directiva, y extraer algunas de sus consecuencias en materia de políticas centradas en la dirección escolar. En la introducción se describe la consideración especial que se atribuye internacionalmente a la dirección de los centros educativos y a su papel en los resultados de los alumnos y en la mejora escolar. La importancia de la profesionalización de la función directiva es considerada, a continuación, a fin de focalizar el marco conceptual. Seguidamente, se efectúa un análisis comparado sobre las diferentes leyes educativas aprobadas en España en dicho periodo. Al objeto de asegurar una comparación homogénea, se ha empleado un mismo patrón de análisis, inspirado en las prácticas internacionales y compuesto por tres criterios y ocho subcriterios relativos a la profesionalización. Se consideran después las evidencias empíricas aplicadas al caso de la Comunidad foral de Navarra y a su anomalía en materia de profesionalización de la dirección escolar. La discusión de ambos tipos de resultados subraya las debilidades del modelo español. Las visiones más innovadoras en materia de profesionalización de la dirección escolar corresponden a la LOPEGCE y a la LOCE. Se concluye con algunas recomendaciones que miran al futuro de la dirección escolar en España, tales como la búsqueda de un modelo de dirección escolar explícito, equilibrado e inspirado en la idea moderna de profesión que se alinee con el consenso internacional sobre la complejidad y la dificultad de la dirección escolar y sus consecuencias; que incorpore la evidencia empírica disponible; y que valore los avances producidos en otros países desarrollados, en el sentido de una profesionalización creciente de la función directiva.

Palabras clave:

Liderazgo, Establecimientos de enseñanza, Legislación educacional, Política educacional, Gestión educacionalIntroduction

The acknowledged importance of the impact of school leadership quality on the quality of schools has progressively been consolidated over decades on an empirical basis. Its direct and indirect effects are regarded as significant in both academic and institutional circles. For instance, the OECD (2017) has highlighted a series of channels through which leadership influences the reality of schools in the following terms:

“School headteachers play a key role in managing schools. They can shape teachers´ professional development, define the school´s educational goals, ensure that teaching practice is directed toward achieving goals, suggest modifications to improve teaching practice, and help resolve problems that may arise in the classroom or among teachers” (p. 120).

This influence, which spreads in a "cascading" manner and ultimately reaches all students in educational institutions, explains the international importance currently attributed to policies focused on school leadership.

There are two types of evidence that, due to their convergence,

underpin this broad consensus and merit emphasis: qualitative or

observational evidence, primarily linked to the effective schools

movement (Purkey and Smith, 1983; Lezotte, 1991); and evidence derived

from quantitative estimates of the association between leadership

quality and school performance (Leithwood Harris, and Hopkins, 2019).

Regarding the first, it is worth recalling Hechinger´s (1981) description, in which he states:

"I have never seen a good school with a bad headteacher, nor a bad school with a good headteacher. I have seen poor schools transform into good ones and, regrettably, outstanding schools rapidly decline. In every case, the rise or fall could be easily traced to the quality of the headteacher" (p.33).

That qualitative perception aligns with the impressions of inspectors and senior officials in the Spanish educational administration, who, with responsibilities in the management of educational institutions, have had the opportunity to closely observe schools and their development.

However, the effective school’s movement, employing naturalistic methodologies, has identified through numerous empirical studies (Klitgaard and Hall, 1973; Purkey, 1983; Lezotte, 1991) the common characteristics of schools that succeed in achieving good results in socially disadvantaged environments. These attributes are known as “correlates” and are distinguished by their consistency and universality; that is, they are repeatedly observed in both primary and secondary schools, on both sides of the Atlantic, and across both the first and second generations of research (Lezotte, 1991). The quality of leadership, specifically in the form of pedagogical or instructional leadership, remains a constant piece of this puzzle.

The second type of evidence comes from purely quantitative analyses,

most often linked to studies examining the association between

leadership quality—or specific aspects or dimensions of it—and school

success, measured by student performance in standardised tests. Reviews

and meta-analyses on this issue are available in the literature (Uysal

and Sarier, 2018; Robinson Hohepa, and

Lloyd, 2009; Leithwood

There are examples of studies that straddle both types of evidence.

Such is the case of the research conducted by Bryk

"

Only 11% of schools with weak leadership achieve substantial improvement in reading. (…) The probability of achieving significant improvements in mathematics is seven times higher in schools with strong leadership than in those with weak leadership" (p. 24).

A significant observation comes from the empirical analysis conducted

by E. A. Hanushek and colleagues (Hanushek Rivkin, and Schiman, 2016) on the school system of the

State of Texas. The authors conclude that improving the quality of

headteachers yields benefits even greater than those obtained by

improving the quality of teachers, in the sense that it comparatively

affects a much larger number of students.

The central objective of this study is to analyse the evolution of the Spanish regulatory framework between 1970 and 2020 from the perspective of the professionalisation of school leadership and to draw the appropriate lessons for policies focused on school leadership. For this reason, we will highlight the importance of the professionalisation of leadership, stemming from the special consideration given internationally to the management of educational institutions and its role in student outcomes and school improvement.

Next, we will conduct a comparative analysis of the various Spanish education laws enacted during this period. To ensure a consistent comparison, we will employ a uniform analytical framework comprising three main criteria and eight plausible sub-criteria related to professionalisation. Subsequently, we will examine the evidence applied to the case of the Autonomous Community of Navarre and its anomaly concerning the professionalisation of school leadership, and we will discuss the findings obtained from both approaches. Finally, we will conclude with some reflections on the future of school leadership in Spain.

The importance of professionalising the management role

The demand for greater professionalisation of school leadership is

one of the key elements of a broad international consensus, firmly

established for several decades in multilateral organisations with

responsibilities in education (Delors

The recognition of the complexity of leadership roles, based on task

analysis (Leithwood

National and international studies agree in recognising that the responsibilities of school leadership constitute a distinct activity from teaching. Leadership roles require a set of conceptual, methodological, and technical skills that are specific to the position and not necessarily required for teaching. While school leadership must certainly be built upon a solid foundation of teaching experience, it also demands its own professional competencies.

Professionalising school leadership, therefore, means incorporating that set of knowledge, skills, and experiences—specific to leadership roles—within the framework of a mature profession. This requires defining an explicit and well-structured model that enables an adaptive evolution in response to contextual changes, guided by a constructive regulatory approach.

The Australian Council of Professions (2004) articulated a robust and contemporary vision of the concept of a profession in the following terms:

In this definition, the characteristic features of well-established professions are easily recognisable, and it highlights the importance attributed to three key components: expert knowledge—organised and transferable—specific to the profession; the professional or practice-based community; and ethical obligations.

The professionalisation of an activity leads not only to improved performance and its consequent impact but also, as a result, to its social recognition. As we have noted elsewhere (López Rupérez, 2014):

"

The social acceptance of a profession, its recognition, and prestige are linked, in one way or another, to the ability of its members to effectively apply an organised body of knowledge and skills in the practice of their profession and in solving the characteristic problems it entails. The essence of a successful professional practice lies in the effective utilisation of this expert knowledge base" (p.76).

These two aspects of professionalisation—prestige and organised knowledge—reinforce each other, creating a virtuous cycle that, considering the available evidence, is one of the key tools for advancing the education system as a whole. Given this, it is unsurprising that, despite the distinct cultural traditions of the United States and France, both have chosen to assign school leadership a specific professional status, separate from teaching and, therefore, not temporary. In other words, according to both models, a school leader, even if they originate from the classroom, will never return to it (López Rupérez, 2024).

Ultimately, the professionalisation of school leadership ensures, with a high degree of certainty, the quality of school management—understood in a broad sense—and its impact on the overall quality of the education system.

The evolution of regulatory frameworks regarding the professionalisation of school management in Spain: 1970-2020

An analysis of the historical background of legislation on school

leadership in Spain, prior to the period between 1970 and 2020—which

will be examined later—reveals a distinct regulatory approach across

different educational stages. For instance, the Law of 26 February 1953

on the Organisation of Secondary Education (

However, the development of the consolidated text of the Primary

Education Act (1945), through Decree 985/1967 of 20 April, established

the Regulations for the School Headteachers’ Corps for this educational

stage (

This differentiated approach was later rectified through two legislative measures: the first, introduced by the General Education Act (LGE, 1970), which abolished the School Headteachers’ Corps; and the second, contained in the Organic Law on the Right to Education (LODE, 1985), which unified the procedures for accessing leadership positions and, as a general rule, eliminated the direct appointment process.

A pattern for comparative analysis

With the aim of facilitating a consistent comparative analysis of the successive regulatory frameworks in Spain from the perspective of the professionalisation of school leadership, we will rely on a plausible analytical framework, inspired by international practices and structured in the form of criteria and sub-criteria, as defined in Table I.

TABLE I. An Analytical Framework for the Comparative Study of the Professionalisation of School Leadership in Spanish Legislation

| Criteria | Sub-criteria |

|---|---|

| Access to school leadership |

|

| Professional practice |

|

| Professional development |

|

Source: López Rupérez (2024).

The General Education and Educational Reform Financing Act (LGE, 1970)

In the implementation of the LGE, two decrees were issued concerning school leadership: the first, Decree 2957/1972 of 3 October, which abolished the School Headteachers’ Corps and regulated its integration into the Corps of General Basic Education Teachers, or alternatively, allowed members to remain in the abolished corps; the second, Decree 2655/1974 of 30 August, which regulated the exercise of leadership functions in National Colleges of General Basic Education. The procedure of direct appointment remained in place for access to leadership roles in National Institutes of Secondary Education.

Taking Decree 2655/1974 as a reference, the analysis of the corresponding regulatory text allows for the following characterisation, in accordance with the framework described in Table I.

Access to school leadership

In accordance with Article Three, Section One,

To be appointed as the Headteacher of a National College of General Basic Education, candidates must belong to the Corps of General Basic Education Teachers, be assigned to the school, and have completed a minimum of three years of service in state schools at this level (Article Three, Section Two).

Furthermore, regarding the

With regard to the

Professional practice

The conditions of professional practice, as described in Article Two,

focus more on

Professional development

Of the three sub-criteria assigned in Table I to this comparative

criterion, only continuous

In summary, the LGE represents a setback in the professionalisation

of school leadership compared to the previous regulatory framework. This

is not only due to the abolition of the School Headteachers’ Corps and

the consequent reduction in access requirements but also because the

mandatory combination of leadership and teaching, as established by the

law, diminishes the time dedicated to effective school management. Some

authors (Mayorga, 2007) have referred to this regression, citing the

conclusion reached in the Final Report of the Evaluation Commission on

the General Education and Educational Reform Financing Act

(

The Organic Law on the Right to Education (LODE, 1985

The LODE is the first law to develop the provisions set out in Article 27 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978. Within this broad regulatory framework, it establishes the rules governing school leadership in public schools and publicly funded institutions.

Access to school leadership

Article 37 sets out all matters related to

- The headteacher of the school shall be elected by the School Council and appointed by the competent Educational Administration.

- Candidates must be teachers at the school with at least one year of service at the institution and three years of teaching experience.

- The election shall be decided by an absolute majority of the members of the School Council.

- In the absence of candidates, if no candidate secures an absolute majority, or in the case of newly established schools, the relevant Educational Administration shall appoint a provisional headteacher for a period of one year.

Regarding the sub-criterion of

Professional practice

The responsibilities of the headteacher are outlined in Article 38.

These encompass both individual

- Officially represent the school.

- Enforce compliance with laws and current regulations.

- Direct and coordinate all school activities in accordance with

prevailing regulations, without prejudice to the competencies of the

School Council

2 . - Lead all staff assigned to the school.

- Convene and preside over academic events and meetings of all the school´s governing bodies.

- Authorise expenditures in line with the school´s budget and manage payments.

- Endorse official certifications and documents of the school.

- Propose appointments for leadership positions.

- Implement the decisions of the governing bodies within their scope of authority.

- Any other responsibilities assigned by the relevant organisational regulations.

Regarding the tenure of these specific functions, it is established that:

- The headteacher´s term of office is three years.

- The headteacher may be dismissed or suspended before the end of this term if they seriously fail to fulfil their duties, following a reasoned report from the School Council and after hearing from the individual concerned.

Professional development

The law does not address professional development, neither in its

limited form as

Organic Law on Participation, Evaluation and Governance of the Schools

This new law—like the previous one, introduced by a socialist

government—is considered an extension, in terms of schools, of its

predecessor, the LOGSE (1990). It represented a step forward in the

professionalisation of the leadership role, which, given the context and

its regulatory background, can be considered

significant

Access to school leadership

In terms of the

Regarding the sub-criterion of

Professional practice

The LOPEGCE adds, from the very law, competences for the headteacher

that were not present in the previous law (art. 21), among which it is

worth highlighting, in the realm of

Although the School Council retains much of its competences, it no longer appoints the leadership team. And while it sets guidelines, it no longer supervises the general activity of the centre in administrative and teaching aspects.

Professional development

In terms of professional development, undeniable progress is made in

the sense of increasing professionalisation. Thus, programmes for

Organic Law on the Quality of Education (LOCE, 2002)

This was the first educational law from a government led by the Partido Popular. The alternation in the national government, which occurred after the law had come into effect, allowed for its application to be delayed by using a Royal Decree that regulated the implementation schedule. Through this legislative mechanism, it was replaced by another law without being fully implemented. Nonetheless, due to its design, it formally served as a reference for greater professionalisation of school leadership, and in some specific respects, it provided an additional push in that direction.

Access to school leadership

Regarding the sub-criterion

This selective process is managed by a Commission – introduced in Spanish educational legislation – made up of representatives from the educational administrations and, at least 30%, representatives from the respective school (art. 88).

The prior requirement for

Furthermore, the requirement of having a permanent assignment at the centre is removed to link the exercise of the managerial function to the candidate´s demonstrated professional competence and to make mobility possible, facilitating other policies, such as compensatory ones.

Although the duration of mandates is reduced to three years, the possibility of extending them through the renewal mechanism is introduced, even at different institutions.

Professional practice

The headteacher’s competencies are expanded, compared to the

provisions of the LOPEGCE (art. 79), in terms of both

As for the second, the focus is on encouraging collaboration with families, institutions, and organisations, fostering an orderly school climate, promoting improvement plans, and initiating internal evaluation processes within the institution, among other things.

Professional development

In terms of professional development, continuous training is provided through mandatory management training courses, so that headteachers can update their technical and professional knowledge (art. 92).

As for

Finally, in relation to the sub-criterion of

Organic Law of Education (LOE, 2006)

This new educational law, passed by a socialist government, introduced several changes compared to the provisions of the LOCE (Law on Education Quality). These changes represented, to some extent, a return to the model established in previous socialist laws, although some of the elements introduced in the two preceding laws were preserved.

Access to school leadership

Regarding the sub-criterion of

The law reintroduces the requirement of having at least one full school year of seniority at the centre, as well as the submission of a leadership project that includes, among other elements, objectives, action lines, and their evaluation (Article 134). The duration of the term is also reinstated at four years. Candidates from within the same centre are given preference (Article 134.1.c). Beyond the knowledge of the center itself that this measure may favor, it is made difficult by it. to transfer proven leadership knowledge and experience to centres that need it most.

Regarding

Similar to what was established in the LOCE, the

Professional practice

In relation to the LOCE, regarding the competencies of the

headteacher (Article 79), the task of pedagogical leadership is added,

and the reference to greater management autonomy for headteachers to

drive and develop improvement projects is removed. The School Council

regains its role as a governing body, as established in the original

LODE law, along with most of the competencies laid out in that law,

except for the election of the headteacher or the appointment of the

leadership team, for example. However, the Council now has the

possibility of drafting proposals and reports on the functioning of the

school and the improvement of management quality (Article 127). In

conclusion,

Professional development

The issue of

Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE, 2013)

This a law occurred because of political alternation and that its responsible parties are the same as those behind the LOE suggests that this new law would reflect a certain preservation of that model.

Access to school leadership

Regarding the sub-criterion for the

Concerning the

Professional practice

Regarding the headteacher´s competencies (Article 132), most of those

outlined in the LOE are reinstated, although some additional

responsibilities are added, such as promoting experiments, pedagogical

innovations, and educational programmes; fostering the qualification and

training of the teaching staff; and designing the planning and

organisation of the school´s teaching activities, among others.

Therefore, the

Professional development

Regarding the sub-criterion of

Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE, 2013)

This a law occurred because of political alternation and that its responsible parties are the same as those behind the LOE suggests that this new law would reflect a certain preservation of that model.

Access to school leadership

Regarding the sub-criterion for the

Concerning the

Professional practice

Regarding the headteacher´s competencies (Article 132), most of those

outlined in the LOE are reinstated, although some additional

responsibilities are added, such as promoting experiments, pedagogical

innovations, and educational programmes; fostering the qualification and

training of the teaching staff; and designing the planning and

organisation of the school´s teaching activities, among others.

Therefore, the

Professional development

Regarding the sub-criterion of

Empirical evidence applied to the case of the Autonomous Community of Navarre

The Autonomous Community of Navarre constitutes a unique case in Spain regarding the professionalisation of the leadership role, which, in this analytical context, deserves special consideration.

In 2020, we published a quantitative study on leadership in Spain in

the British journal

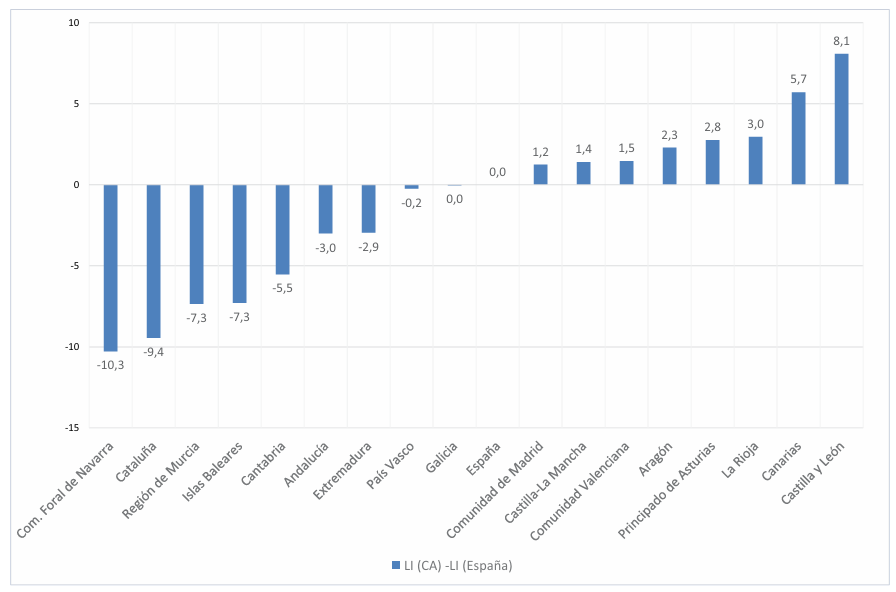

Although the results on the quality of leadership in public secondary education schools across Spain were not good the Autonomous Community of Navarre ranked very poorly on the LI indicator, coming in last place, 9.8 percentage points below the national average.

This study did not aim to provide an explanation for these results. For example, in the extreme case of the Autonomous Community of Navarre, further research, likely qualitative in nature, would have been necessary to gain a deeper understanding of this situation.

Sometime later, the study came to the attention of the Association of High School Headteachers of Navarra (ADIZE), which invited me to present it at their 2023 Meeting in Pamplona. The previous conversations with the attendees and organizers, as well as the subsequent public discussion with high-ranking officials of the Navarra educational administration, provided me with relevant information, at least to formulate a notably plausible explanatory hypothesis. It turns out that the corresponding educational administration had dispensed with the consolidation of the salary complement, associated with the continued and successful exercise of the management function. To have suspended this incentive in the territory was very likely the reason why a very large majority of the principal appointments were being made through the extraordinary procedure.

FIGURE I. Deviations of the values of the integrated leadership indicator LI, compared to the sample value for Spain for public secondary education centres, by autonomous communities

Source: López Rupérez García García

and Expósito Casas (2020)

This led to a designation which, in addition to the potential dissatisfaction it could cause in many cases, prevented thinking ahead about a leadership project, its development, and implementation supported by a suitable leadership team chosen for that purpose. Furthermore, the performance evaluation that should have been positive for the consolidation of the salary supplement was left in suspense. Thus, the following factors were aligning, with a more than likely negative result on the quality of leadership: the non-voluntary nature of the appointment; the improvised planning and consequently improvised leadership action; the elimination of accountability linked to performance evaluation; and the various interactions between these factors.

One of the positive effects of the ADIZE Meeting has been that the Autonomous Community of Navarra, after decades of neglecting this element of professionalisation of the leadership function, has rectified, and in the sixth final provision of its budget law (B.O.E of 26 March 2024), it amends the Foral Legislative Decree of 30 August 1993, which approves the consolidated text of the Statute of Personnel at the service of the Public Administrations of Navarra, introducing the mentioned incentive and its conditions.

Discussion and conclusions

Table II synthesises the regulatory evolution analysed above, with 0 representing the baseline or reference level; + indicates progress in professionalisation compared to the previous law; = signifies the absence of substantial changes compared to the previous law; and - represents a regression in professionalisation relative to the previous law. It clearly shows, for example, the lack of stability in the model, except for performance evaluation, linked to incentives and introduced in the LOPEGCE. The progressive nature of responsibilities does not always align with the necessary increase in authority to carry them out. The most innovative views in the search for a new balance that strengthens the professionalisation of school leadership undoubtedly belong to the LOPEGCE and the LOCE. It is to their contributions that this weak constructive dynamic observed in the overall analyses can be attributed.

TABLE II. Evolution of Spanish legislation on the professionalisation of school leadership from 1970 to 2020.

| Criteria | Sub-criteria | LGE | LODE | LOPEGCE | LOCE | LOE | LOMCE | LOMLOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to school leadership | -Appointment to the position -Initial training -Accreditation for the exercise of leadership functions |

0 0 0 |

- - = |

= + + |

+ + - |

- - = |

+ + = |

- = = |

| Professional practice | -Authority -Responsability |

0 0 |

- + |

+ + |

+ + |

- + |

+ + |

- + |

| Professional development | -Continuous training -Performance evaluation -Career progression |

0 0 0 |

- = = |

+ + = |

= = + |

- = - |

= = = |

+ = = |

Note: 0 represents the reference level; + denotes progress in professionalisation compared to the previous law; = indicates no substantial changes compared to the previous law; - signifies a regression in professionalisation compared to the preceding law.

From the evolution of Spanish basic legislation on school leadership in public schools between 1970 and 2020, it can be inferred that there has been a lack of an explicit and well-articulated model, whose pillars—often unclear and lacking a well-founded justification—must be identified by the researcher through an interpretation of the laws. This poor practice, which at times borders on arbitrariness or a tacit ideological influence and moves away from a rational approach to educational policies, has hindered the development of a calm and well-founded debate as a precursor to political agreement.

For instance, from the perspective of the regulatory frameworks, there has been a seesawing between models of initial training depending on whether it occurs before or after the selection process, with no effort made to rationally justify the preference for one over the other. The same can be said regarding selection versus election as the process for appointing a headteacher, where in the latter case, an underlying ideological conception can be sensed, albeit hidden under a formal convergence around the novelty of the Commission introduced by the LOCE.

In the modifications made concerning the powers or competencies of the headteacher, the series of shifts characteristic of a conflict between a more professionalising vision of the headteacher role and one more focused on preserving the School Council´s original character as a governing body has predominated in all laws since democracy was reestablished. This is especially reflected in the School Council model and the fluctuating proportions in the composition of the selection committee, as well as in the shifts in the relative importance between the Administration and the School Council/Staff, depending on the political stance of the law.

In such a key area as the management of leadership talent through professional development, it can be observed that, while the evaluation of the headteacher´s performance has become consolidated over time, no professional career model has been established. Vertical mobility, or promotion, is only addressed in some laws and is presented as a vague ideal whose development, after so many decades, is still to be formulated and implemented. Horizontal mobility is only hinted at in the LOCE.

Continuous professional development is referenced in various regulations, though its prescriptive nature has not been clearly established in all legislative processes. Only the consolidation of the recognition of the salary supplement linked to the headteacher role is firmly established, serving as a valuable extrinsic incentive for headteachers, with a notable repercussion on the quality of leadership in public schools, as evidenced by the analysis of the Navarra case on an empirical basis, to the point of prompting a regulatory correction in the right direction.

Beyond the validation of the diagnostic tool used in the referenced case due to its capacity to detect the undesired effects of this procedural anomaly—the analyses have highlighted that neglecting certain elements of professionalisation is associated with a decline in the quality of headteacher functions, likely having a negative impact on the results that these same students in Navarra could have achieved under more favourable leadership conditions in their schools.

The comparative analysis also draws attention to the fact that, more than half a century ago, and in a pre-democratic social and political context, the General Education Law benefited from both a White Paper and an evaluation of its effects (Comisión de Evaluación de la Ley General de Educación y Financiamiento de la Reforma Educativa, 1976). The absence of these best practices in the vast majority of laws passed during democracy aligns with the opinion of a prestigious and diverse panel of experts, who have considered the failure to base policies “on knowledge, empirical evidence, and research” as one of the main weaknesses of governance within the Spanish education system (López Rupérez, 2021).

It is worth adding to the above a notable territorial dispersion in the criteria for the regulatory development, by the Autonomous Communities, of the basic State legislation as the Federation of Associations of High School Headteachers has highlighted (FEDADI, 2022).

In view of all the above, it can be concluded that Spain faces the important task of finding a balanced school leadership model inspired by the modern idea of a profession; one that takes into account the international consensus on the complexity and difficulty of school leadership and its consequences; incorporates available empirical evidence; values the progress made in other developed countries towards the growing professionalisation of the headteacher role; and, finally, does not hinder the use of proven effective school leadership—but rather promotes it—as a fundamental tool for educational compensation. This is one of those evidence-based policies, accepted internationally, that would contribute to increasing the real equality of opportunities within the Spanish education system.

The political agreement, essential for promoting substantial and sustainable advances, must be based on an explicit model that serves as the foundation for a calm analysis and public deliberation—as befits a pluralistic society—in which serving headteachers are involved.

Notes

References

Australian Council of Professions (2004).

Comisión de Evaluación de la Ley General de Educación y

Financiamiento de la Reforma Educativa (1976).

Bender, P., Allensworth, E., Bryk A. S., Easton J. Q. y Luppescu S.

(2006).

B.O.del E. (1953). Ley sobre Ordenación de la Enseñanza Media. 26 de

febrero de 1953. B.O. de E. No. 58.

B.O. del E. (1967). Decreto 985 de 1967, por el que se aprueba el

Reglamento del Cuerpo de Directores Escolares. 20 de abril de 1967. B.O.

del E. No.117.

B.O.del E. (1976). Decreto 186 de1976, por el que se crea la Comisión

de Evaluación de la Ley General de Educación y Financiamiento de la

Reforma Educativa. 6 de febrero de 1976. B.O. del E. No.37.

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S. y Easton,

J. Q. (2010).

Delors, J. et al. (1996)

Hanushek, E. A.; Rivkin, S. G.; Schiman, J. C. (2016). Dynamic

effects of teacher turnover on the quality of instruction.

Hechinger, F. M. (1981). Citado en

FEDADI (2022). Informe sobre la selección de directores. FEDADI.

Fullan, M. (2014).

Klitgaard, R.E. y Hall, G.R. (1973). Are there Usually Effective

Schools?

Lezotte, L.W. (1991).

Leithwood, K., Seashore, K., Anderson, y Wahlstrom, K. (2004).

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., y Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims

about successful school leadership.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., y Hopkins, D. (2019). Seven strong claims

about successful school leadership revisited.

LGE (1970). Ley 14 de 1970, General de Educación y Financiamiento de

la Reforma Educativa. 4 de agosto de 1970. B.O. del E. No.187.

LODE (1985). Ley Orgánica 8 de 1985, reguladora del Derecho a la

Educación. 3 de julio de 1985. B.O.E. No. 159.

LOCE (2002). Ley Orgánica 10 de 2002, de la Calidad de la Educación.

23 de diciembre de 2002. B.O.E. No.307.

LOE (2006). Ley Orgánica 2 de 2006, de Educación. 3 de mayo de 2006.

B.O.E. No.106

LOMCE (2013). Ley Orgánica 8 de 2013, para la mejora de la calidad

educativa. 9 de diciembre de 2013. B.O.E. No.295.

LOMLOE (2020). Ley Orgánica 3 de 2020, por la que se modifica la Ley

Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. 29 de diciembre de 2020.

B.O.E. No. 340.

LOPEGCE (1995). Ley Orgánica 9 de 1995, de la participación, la

evaluación y el gobierno de los centros docentes. 20 de noviembre de

1995.B.O.E. No.278.

López Rupérez, F. (1994).

López Rupérez, F. (2014).

López Rupérez, F. (2021).

López Rupérez, F. (2024). La función directiva en el contexto nacional e internacional.

En Gairín, J.

López Rupérez, F., García García, I., y Expósito Casas, E.

(2017).

López Rupérez, F., García García, I. y Expósito Casas, E.

(2019).

López Rupérez, F., García García, I. y Expósito-Casas, E. (2020).

School Leadership in Spain. Evidence from PISA 2015 assessment and

Recommendations.

Mayorga, A. (2007). La dirección educativa y su problemática.

Naciones Unidas (2015).

OECD. (2017).

Pont, B., Nusche, D., y Moorman, H. (2008 a).

Pont, B., Nusche, D., y Moorman, H. (2008 b). Improving School

Leadership. Volume 2: Case Studies on System leadership. OECD

Publishing.

Purkey, S. C. y Smith, M. S. (1983) Effective Schools: A Review.

Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., y Lloyd, C. (2009).

Sammons, P. (1995).

UNESCO (2024). Global Education Monitoring Report 2024/5: Leadership

in education – Lead for learning. UNESCO.

Uysal, S. y Sarier, Y. (2018). Meta-analysis of school leadership

effects on student achievement in USA and Turkey.

Información de contacto / Contact info: Francisco López Rupérez. Universidad Camilo José Cela. E-mail: flopezr@ucjc.edu