Second Chance Schools: An Exploratory Scoping Review

Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad: una revisión sistemática exploratoria

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-689

Celia Camilli Trujillo

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7181-0068

Mónica Fontana Abad

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4451-4639

Lorena Pastor Gil

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7055-9908

Abstract

Early school leaving is linked to unemployment, social exclusion, poverty and poor health. There are many reasons why some young people leave their studies and training prematurely, such as the organization of the education system, the school climate and relationships between teachers and students. Second Chance Schools (E2C) offer an educational model designed for young people who have dropped out of the traditional education system or have failed in it due to social, financial and/or family issues. These schools offer a second chance for them to continue and complete their education, thus improving their future academic and employment prospects. The aim of this scoping review is to discern the issues that have been studied in E2C research and the main characteristics and outcomes of these educational programs on the young people who participate in these schools. Four databases were consulted (SCOPUS, WOS, DIALNET and ERIC). A total of 145 documents were found, with the final sample being 17 manuscripts. Most of the young people attending the schools are males between the ages of 15 and 24 with culturally diverse and vulnerable socioeconomic backgrounds. The findings indicate that E2Cs impact a number of functions of education, ranging from reentry and educational certification to preparation for employment, personal development, and social integration. They focus on improving skills, fostering self-knowledge and inclusion, supporting emotional wellbeing and active participation in society and the job market. The student profiles and the types of programs and interventions at these schools are also addressed. The study has helped consolidate and disseminate knowledge about how E2C works and its pedagogical implications. Conclusions are provided with regard to public policy in education.

Keywords:

scoping review, second chance schools, vulnerable youth, competencies, early school leaving, school failure, school absenteeism, educational reintegration, inclusive education, alternative education

Resumen

El abandono escolar prematuro está vinculado al desempleo, la exclusión social, la pobreza y la mala salud. Existen muchas razones por las que algunos jóvenes abandonan prematuramente sus estudios y su formación como son la organización del sistema educativo, el clima escolar y las relaciones entre profesores y alumnos. Son las Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad (E2C) un modelo educativo diseñado para jóvenes que han abandonado el sistema educativo tradicional o han fracasado en él debido a problemas sociales, económicos y/o familiares. Estas escuelas ofrecen una segunda oportunidad para que puedan continuar y completar su educación mejorando así sus perspectivas de futuro tanto académicos como laborales. El objetivo de la revisión es conocer qué estudian las investigaciones acerca de las E2C así como las principales características y resultados de sus programas formativos en los jóvenes que participan en estas escuelas a través de una revisión sistemática exploratoria. Las bases de datos consultadas han sido cuatro (SCOPUS, WOS, DIALNET y ERIC). Un total de 145 documentos fueron encontrados siendo la muestra final de 17 manuscritos. La mayoría de los jóvenes que asisten a las escuelas son varones entre los 15 y 24 años y de diversidad cultural que provienen de contextos socioeconómicos vulnerables. Los hallazgos indican que las E2C impactan en diversas funciones de la educación, desde el reingreso y la certificación educativa, hasta la preparación para el empleo, el desarrollo personal, y la integración social. Estas se enfocan en mejorar habilidades, fomentar el autoconocimiento y la inclusión, apoyar el bienestar emocional y la participación activa en la sociedad y el mercado laboral. Asimismo, se aborda el perfil de los estudiantes y los tipos de programas e intervenciones de estas escuelas. El estudio ha contribuido a consolidar y difundir el conocimiento sobre el funcionamiento de las E2C y sus implicaciones pedagógicas. Se ofrecen implicaciones para las políticas públicas educativas.

Palabras clave:

revisión sistemática exploratoria, escuelas de segunda oportunidad, jóvenes vulnerables, competencias, abandono escolar temprano, fracaso escolar, absentismo escolar, reinserción educativa, educación inclusiva, educación alternativaIntroduction

On average, 9.5 % of 18-24 year olds in the European Union (EU) left their education and training early in 2023, with more young men than women dropping out (11.3 % vs. 7.7 %). The countries with the lowest dropout rate were Croatia, Greece, Poland and Ireland (<5 %) while the highest dropout rate was recorded in Romania (16.6 %), followed by Spain (13.7 %), Germany (12.8 %) and Hungary (11.6 %). While there are still large differences between EU countries today, 16 EU countries have already achieved a school dropout rate of less than 9 %, thus meeting the EU target for 2030 (Eurostat, 2023, Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2023).

Several studies have shown that there are individual risk factors such as age, behavioral problems and low academic performance, and school-related factors such as student-teacher ratio, financial resources and the quality of school management that influence school absenteeism (Contreras-Villalobos et al., 2023; Espinoza et al., 2014). Not only do young people lose interest in attending school, but the system itself somehow ends up “expelling” them (Martínez-Valdivia and Burgos-Garca, 2020; Torkashvand et al., 2022). Pong and Ju (2000) found that the educational environment created by the family is also directly related to the educational outcomes of their children and their chances of remaining in the education system.

Within this complex, multifactorial framework, the main causes of early school leaving are associated with socioeconomic status, family background, the job search, ethnicity, family disintegration and families’ low expectations with regard to education (European Commission, 2022). Moreover, individuals that are left out of the education system can easily become excluded from social, cultural and economic dynamics. Recent research by Bernard and Michaud (2021) on school leaving reveals that many students leave school because they feel that working is a much more attractive alternative. However, it is not easy for people without qualifications to gain access to jobs, which makes it important to receive training that offers support for the development of personal and professional projects. UNESCO (2024) estimates that the global cost of school leaving and lack of education amounts to 10 billion dollars a year. The message in this report is clear: education is a strategic investment, one of the best possible investments for individuals, economies and society as a whole.

So-called “Second Chance

Schools

This approach breaks with traditional models that merely address the “professional situation” or the “discovery” of work environments. Instead, they accept that each young person’s autonomy depends largely on the connection between their capabilities and the resources made available to them both at work and in training. These schools create ties with local authorities, social services, associations and the private sector, the latter in particular with a view to offering possible training opportunities and jobs. It is an approach to teaching and counselling that focuses on the needs, desires and abilities of each student, where active learning is encouraged. The teaching modules are flexible, allowing for a combination of basic skills development (numeracy, literacy, social skills, etc.) and practical training at companies, and building skills through Information and Communication Technologies (European Commission, 2001; Soto et al., 2021). However, each country adapts these principles to its pedagogical model according to educational and social needs.

E2Cs are still a relatively limited initiative, so this exploratory scoping review (ESR) aims to provide insight into the topics of research on these schools as well as the characteristics and outcomes of their educational programs for the young people attending them. To date, no scoping reviews (SR) on E2Cs have been found, with the exception of two studies. The critical, non-systematic review by Barrientos (2022) seeks to discern the differences between alternative education and E2Cs: the former is associated with pedagogical methods like Montessori or Waldorf, while the latter is a component of alternative education designed for the inclusion of young people with needs that are not addressed in uniform school environments. The other study, the review by Paniagua (2022), focuses on second chance programs and briefly mentions the experiences of these schools: they are based on a model with certain shared common principles, such as comprehensive support for the individual and the adaptation of tailored paths that combine basic competencies with vocational training through work experience.

Method

SR is a research method that involves identifying and summarizing all the existing research available on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive overview, thus ensuring the transparency and replicability of the study. It offers a certain degree of cumulative knowledge about research —educational research, in this case— in which the SR and meta-analysis production is lower than in other disciplines (Philip, 2020). This ESR (exploratory scoping review) is useful for mapping the literature on emerging or evolving topics or for identifying gaps (Mak and Thomas, 2022). In this case, it is exploratory because it aims to provide a general overview of the schools.

The descriptors used were "escuelas de segunda oportunidad", "second chance program", "second chance schools" and "écoles de la deuxième chance", the search strings in WOS were (((((TI=("escuelas de segunda oportunidad")) OR AB=("escuelas de segunda oportunidad")) OR TI=("second chance program")) OR AB=("second chance program")) OR TI=("écoles de la deuxième chance")) OR AB=("écoles de la deuxième chance") OR TI=("second chance schools")) OR AB=("second chance schools"), in SCOPUS (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("escuelas de segunda oportunidad") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("second chance program") OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("écoles de la deuxième chance")) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("second chance schools")) and in ERIC TITLE ("escuelas de segunda oportunidad") OR ABSTRACT ("escuelas de segunda oportunidad") OR TITLE ("second chance program") OR ABSTRACT ("second chance program") OR TITLE ("écoles de la deuxième chance") OR ABSTRACT ("écoles de la deuxième chance") OR TITLE ("second chance schools") OR ABSTRACT ("second chance schools").

To analyze the general characteristics of the selected studies,

frequencies and percentages were assessed in Microsoft Excel, and to

identify the results of the schools and their programs, an inductive

qualitative analysis was conducted manually (Bingham and Witkowsky,

2022). This type of analysis is an emergent strategy in which new codes

or concepts emerge during the coding process. It is a “bottom-up”

analytical strategy and therefore is not based on predetermined

categories to be searched for in the text. Finally, the methodological

quality of the primary research was assessed using three scales: COREQ

(

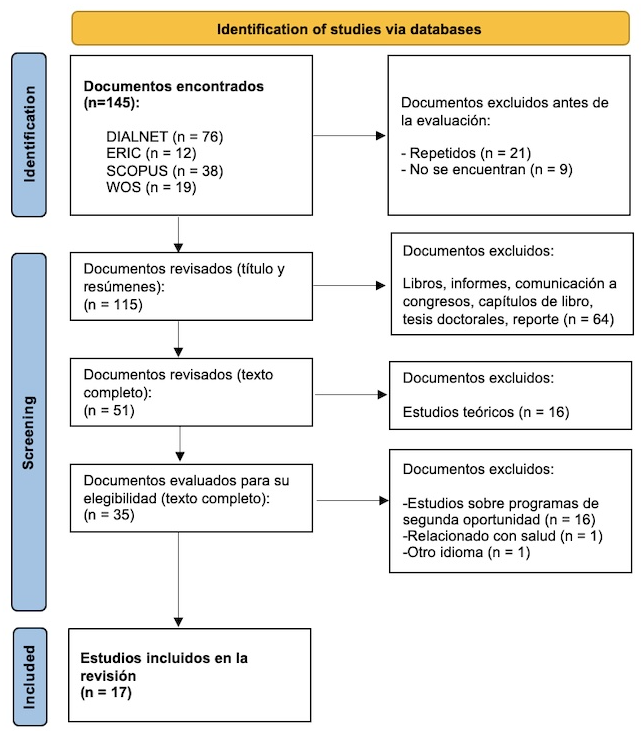

Following three rounds of review, 17 of the 145 documents found met the inclusion criteria. The flow chart (Figure I) shows the reasons why 127 papers were excluded. Articles on “second chance programs” were also discarded if they were related to “compensatory programs” and thus were unrelated to the topic of interest.

FIGURE I. Flowchart

Source: Compiled by the authors

Findings

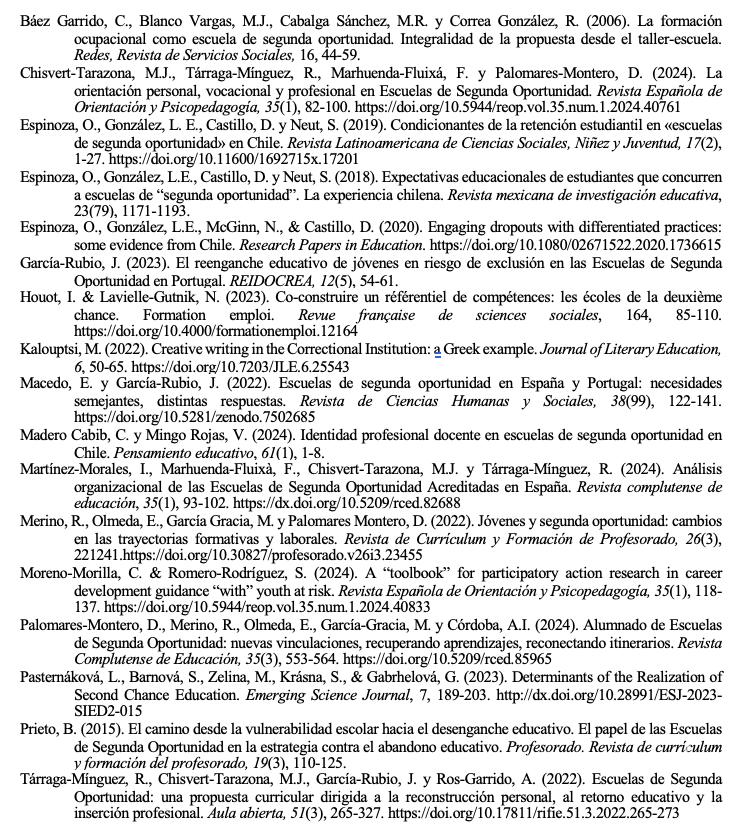

A general description is given below of the characteristics of the selected articles, outlining the profiles of the students at E2Cs, their programs and pedagogical methodologies, and the main findings in terms of the training of these youths. The bibliographic references of the 17 papers included can be found in Appendix 2.

General features of the studies

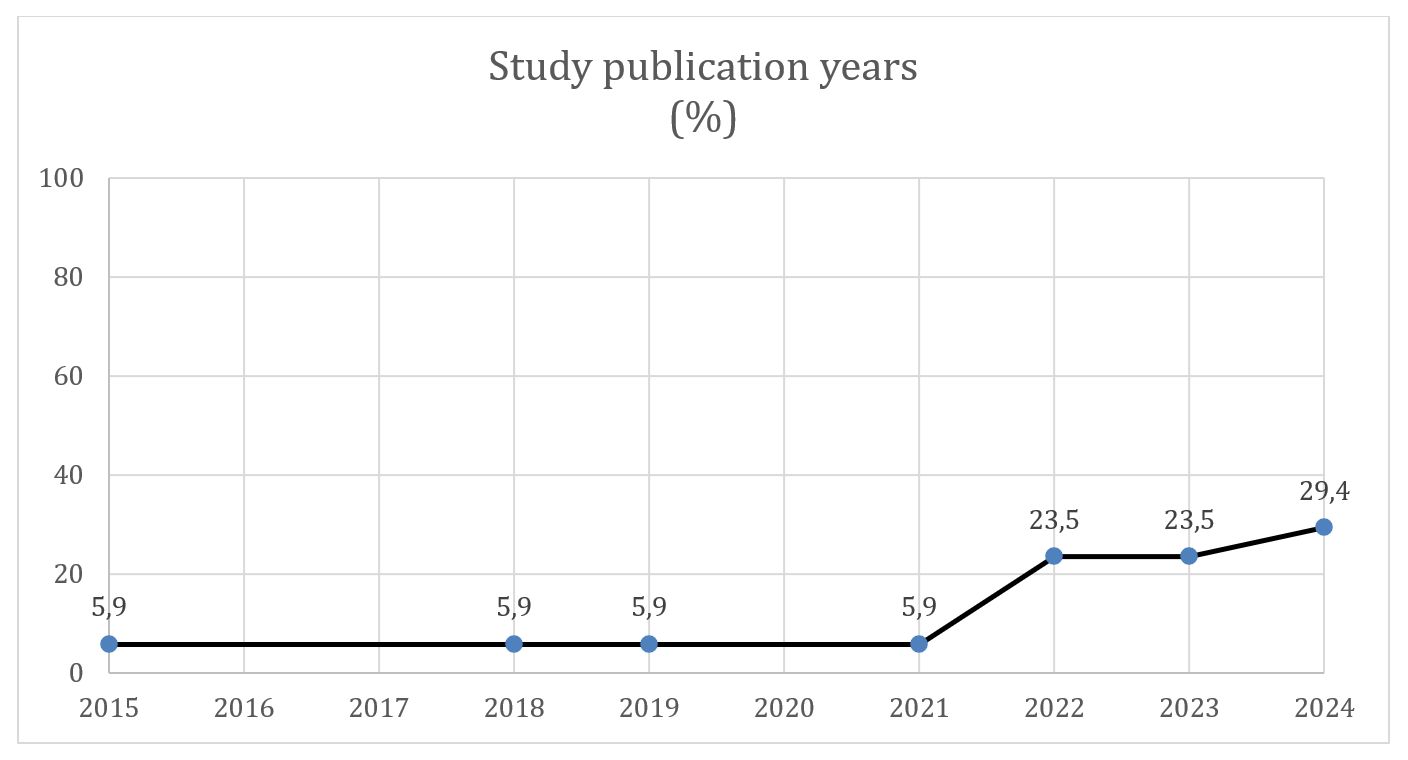

The 17 documents included were published between 2015 and 2024. An increase is seen in the number of publications from 2022 onwards, after which time 76.5% of the studies were conducted. The highest numbers of publications are from 2022, 2023 and 2024 (23.5% and 29.4%, respectively) (Graph I).

GRAPH I. Years of publication of the studies found

Source: Compiled by the authors

58.8% of the articles are written in English and 41.2% in Spanish. 77.2% were published in Europe. Almost half of the authors are from Spain (47.6%), 19% are from Chile, 9.5% from Belgium and 4.8% from Greece, France, the United States, Portugal and Slovakia, respectively. All the studies were conducted at universities, and the largest body of research was published by the University of Valencia (Spain) (70%), which boasts a consolidated E2C research group. 70.6% of the articles were published in journals specializing in Education and the remaining 29.4%, in Social Sciences journals.

In terms of the aims of the studies, one group of papers focuses on competency development (Houot and Lavielle-Gutnik, 2023) and career paths (Merino et al., 2022), creative writing (Kalouptsi, 2022), career orientation (Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024), and personal, vocational and professional guidance (Chisvert-Tarazona et al. 2024), expectations about school (Espinoza et al., 2016) and the future (Palomares-Montero et al., 2024), educational re-engagement (Espinoza et al., 2020, García-Rubio, 2023) and strategies to combat school leaving (Prieto, 2015). Other studies discuss the organizational structure of the schools (Martínez-Morales et al., 2024) and their curriculum (Tárraga- Mínguez, et al., 2022), the experience of the Valdocco workshop-school (Báez Garrido et al., 2006), the perceptions of students, teachers and school leaders (Espinoza et al., 2019) in relation to the determining factors of success or failure of the programs (Pasternáková et al., 2023), the professional identity of schools’ teachers (Madero Cabib and Mingo Rojas, 2024) and a comparative study between Spain and Portugal (Macedo and García-Rubio, 2022).

Seven of the 17 studies are qualitative, and data analysis and research reporting are the methodological aspects with the highest number of positive ratings; four are quantitative, all with a low risk of bias; and three are mixed, and it is not always clear how, at what stage and why the quantitative and qualitative data have been combined. Only three studies were left out of the methodological quality assessment, because they were educational experiences (Appendix 1). Table I summarizes the general characteristics of these studies.

TABLE I. Summary of the studies included

| Authors and year | Aims | Context, sample and methodological design | Place |

| Báez Garrido et al. (2006) | Occupational vocational training in diverse trades with a comprehensive approach spanning several areas of intervention | Valdocco School-Workshop Experience Ages 16-22. Program=psychosocial guidance, family and social and community intervention, socio-cultural animation, physical development and sports, complementary activities and instrumental training |

Spain |

| Chisvert-Tarazona et al. (2024) | Personal, vocational and professional guidance in E2O, analyzing guidance models and processes for transitional training mechanisms for young people in vulnerable situations | Mixed study Semi-structured interviews= 24 principals/directors of studies in E2O, 9 teachers/counselors in secondary schools and 10 company mentors Survey= 351 E2O graduates Evaluation of school activity indicators = 1592 E2O graduates |

Spain |

| Espinoza et al. (2019) | To understand the perceptions that students, teachers and directors have regarding aspects that might influence success or failure in the retention of adolescents involved in educational experiences referred to as “E2C” in Chile | Qualitative study 56 students Semi-structured interviews=56 (5 students, one teacher and one representative of the management team from each of the eight integrated youth and adult education centers in the Metropolitan Region) |

Chile |

| Espinoza et al. (2018) | To analyze the perceptions of young people who dropped out of traditional school and enrolled at “second chance” institutions about their expectations for schooling | Qualitative-descriptive study Ages 14-18 40 students Semi-structured interviews=40 semi-structured interviews with adolescents at E2Cs (5 students from each of the Integrated Youth and Adult Education Centers in the 8 selected municipalities of the Metropolitan Region) |

Chile |

| Espinoza et al. (2020) | To identify activities that enable young people who do not attend school to enroll in so-called “remedial” schools currently operating in Chile in order to become re-engaged | Quantitative survey-based study Ages 14-18 2,199 students Latent class analysis to classify students into four different groups |

Chile |

| García-Rubio (2023) | Educational re-engagement of young people at risk of exclusion at E2Cs in Portugal | Qualitative study Ages 15-25 Semi-structured interviews= 6 E2C leaders Focus group= members of the schools |

Portugal |

| Houot and Lavielle-Gutnik (2023) | Co-construction of a competency benchmark in E2O for unqualified young people | Educational experience Ages 16-22 10 schools, interviews (N= 40) and 9 focus groups (N= 6) Regional seminars= between 60 and 170 E2C professionals Analysis of 400 surveys |

France |

| Kalouptsi (2022) | Creative writing at Diavata Correctional Facility in Greece | Educational experience - creative writing Adults from 30-35 years old and one 50 year-old Five participants=two Albanians, two Greek Roma and one Kurd Creative writing activity at a correctional facility |

Greece |

| Macedo and García-Rubio (2022) | E2O in Spain and Portugal, analyzing the needs of young people and the training proposals offered in the two countries | Qualitative study Youths aged 15-29 from Spain Youths aged 15 and 25 years old from Portugal. Semi-structured interviews=10 E2O leaders in Spain and 6 E2C leaders in Portugal Discussion group= Portuguese E2C leaders |

Spain and Portugal |

| Madero Cabib and Mingo Rojas (2024) | To qualitatively explore the professional teaching identity of teachers working in second chance schools in Santiago de Chile, where children and young people resume their interrupted educational paths | Qualitative-exploratory study 12 teachers Semi-structured interviews Focus groups: different members of the educational communities (students, family, professionals and leadership team) |

Chile |

| Martínez-Morales et al. (2024) | To identify the organizational dimensions of accredited E2Os in Spain and to assess the extent to which these organizations promote the social inclusion of their students | Mixed study Ages 15-29 Semi-structured interviews=24 interviews (16 individual and 8 joint interviews) with members of E2O leadership teams, in which 32 leaders participated Survey= 351 young people |

Spain |

| Merino et al. (2022) | Effect of E2O training on the competency and employment paths of vulnerable young people. | Quantitative-descriptive study Ages 15-29 1,592 young people Analysis of descriptive techniques and multiple regression and multinomial logarithmic regression models |

Spain |

| Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez (2024) | Successful tools used in career development guidance processes with at-risk youths, especially those with socio-cultural vulnerability | Qualitative study - case study - research -action - qualitative career assessment 26 year-old= case study (case chosen from a group of 22 young people at E2Os) Collaborative ethnographic research |

Spain |

| Palomares-Montero et al. (2024) | Analysis of the profile, ties and future expectations of E2O students | Quantitative survey-based study Ages 15-30 1,119 young people Content validation, descriptive and bivariate analysis and logarithmic regression models |

Spain |

| Pasternáková et al. (2023) | Determining factors of success or failure of second chance programs in education, from the teachers’ perspective | Quantitative study-instrument validation Ages 18-24 1,038 teachers (56.45% female and 43.55% male) Creation of a survey about second chance education indicators =26 questions (Likert scale) Factor analysis |

Slovakia |

| Prieto (2015) | Role of E2Os in the strategy to combat early school leaving, focusing on the path from school vulnerability to educational disengagement | Qualitative study-case study Ages 14-25 In-depth interviews=10 young people + teaching staff and educational leaders Focus group=school coordinators, faculty and administrative staff |

Spain |

| Tárraga-Mínguez et al. (2022) | E2O and its curricular proposal for the personal reconstruction, return to education and job placement of young people at risk of exclusion | Mixed study Ages 20-24 Semi-structured interviews=24 interviews with E2O principals and/or directors of studies, 10 supervisors and/or company managers, 9 teachers and counsellors who tutor the young people Survey= 351 young people |

Spain |

Source: the authors

Note: In Spain, these schools are referred to as E2O

Profiles of students at E2Cs

The students that attend E2Cs have a profile with common features across different contexts and countries. In socioeconomic and family-related terms, the students tend to come from vulnerable and dysfunctional backgrounds, with situations of abuse, domestic violence and conditions of poverty. In Chile, Espinoza et al. (2019) and Madero Cabib and Mingo Rojas (2024) highlight the high degree of vulnerability of these young people, who tend to fall behind in school and experience precarious living conditions. In Spain, Martínez-Morales et al. (2024) and Merino et al. (2022) also mention the complexity of the family situations of these students, most of which come from households with financial difficulties.

In terms of age, the majority of E2C participants are young people who have dropped out of the traditional education system. In France, for example, Houot and Lavielle-Gutnik (2023) indicate that the students are between 16 and 22 years old, while in Chile, Espinoza et al. (2019) report an age range of 15 to 18 years old, and in Slovakia, Pasternáková et al. (2023) report an age range of 18 to 24 years old. In terms of gender, there is a greater prevalence of male students. In Spain, males account for 69.57% and 67.79% according to Martínez-Morales et al. (2024) and Merino et al. (2022), respectively.

In relation to previous educational experiences, E2C students often have a history of school failure and lack of motivation. In Chile, Espinoza et al. (2019) mention discouragement and low academic performance, leading to school repetition. Similarly, in Spain, Merino et al. (2022) indicate that many students have low academic levels when they enroll in E2C, with 46% in the 2nd year of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO). In other countries, such as Greece, it has also been observed that the students come from low socioeconomic settings and have limited educational backgrounds (Kalouptsi, 2022).

E2C students often face situations of vulnerability and risk, such as behavioral problems, disabilities, addictions and criminal conduct. In Chile, many young people have been referred to detention centers or to the National Service for Minors due to family issues or drug use (Espinoza et al., 2019). In Portugal, García-Rubio (2023) highlights disinterest in school stemming from negative experiences and complex personal circumstances.

Finally, E2Cs serve a diverse population in terms of nationality and ethnicity. In Spain, Martínez-Morales et al. (2024) report that most of the students are born in Spain, but a significant percentage come from other Spanish- or non-Spanish-speaking countries.

E2C programs

E2Cs implement diverse educational interventions tailored to the needs of the students, focused on providing skills and competencies for the job market. The most common types of intervention include vocational and occupational training, encompassing trades such as masonry, carpentry, electricity, painting and welding, accompanied by social and personal skills (Báez Garrido et al., 2006). In Chile, E2Cs offer job workshops and recreational activities (Espinoza et al., 2019), while in Slovakia, the development of professional skills and communication and leadership competencies is highlighted (Pasternáková et al., 2023). Likewise, E2Cs focus on obtaining educational certification, such as the Compulsory Secondary Education Diploma in Spain or access to Vocational Training, and on certification and assessment programs aimed at helping the young people obtain competencies sought after in the job market (García-Rubio, 2023; Houot and Lavielle-Gutnik, 2023; Merino et al., 2022). Psychosocial intervention is also essential, providing tailored follow-ups and job orientation (Báez Garrido et al., 2006). Similarly, support for students with family or behavioral problems is also highlighted (Espinoza et al., 2019). Family involvement is another key aspect, through programs that foster collaboration and the creation of bonds of trust between young people and professionals (García-Rubio, 2023). Another important aspect is participation in the labor intermediation process, through dual vocational training programs (Pasternáková et al., 2023), which combine theory and practice. E2Cs also promote social inclusion and social skills development, acting as a bridge toward education and social inclusion, especially for students from vulnerable backgrounds (Pasternáková et al., 2023). E2Cs feature tailored training paths adapted to the individual needs of the students through diagnostic assessments and a flexible approach (García-Rubio, 2023; Moreno- Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). Through ongoing, non-punitive assessments focused on the learning process, the training paths can be adjusted to match the students’ progress and needs (Merino et al., 2022). Moreover, there is constant collaboration with multidisciplinary services, which favors comprehensive support in line with each young person’s needs (Pasternáková et al., 2023).

Pedagogical methodologies developed at E2Cs

E2Cs implement a range of methodologies adapted to the needs of students from vulnerable backgrounds who have had poor experiences in the traditional education system. One of the main methodologies is active, participatory learning, which promotes student interaction and involvement, making learning more relevant (Pasternáková et al., 2023). They also implement project-based work, which allows students to apply their knowledge in practical situations and choose their own training paths (García-Rubio, 2023). In addition, E2Cs personalize the teaching to meet the individual needs of each student, adapting curricula to their progress and difficulties, and using individualized tutoring to offer tailored support (Báez Garrido et al., 2006).

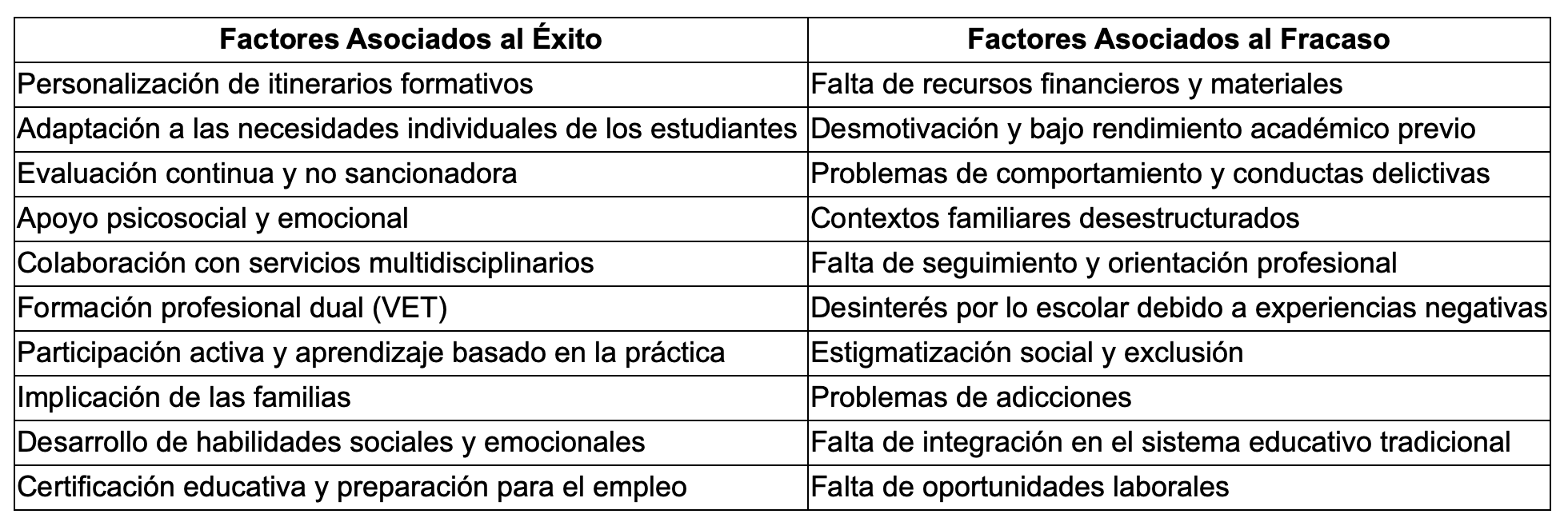

Another key methodology is practice-based learning, which facilitates the acquisition of competencies through real-life experiences, integrating theory and practice (Houot and Lavielle- Gutnik, 2023). Dual vocational education and training (VET), which combines both approaches, prepares students for the job market (Pasternáková et al., 2023). In terms of assessment, E2Cs use ongoing, non-punitive assessments focused on the learning process, as well as self-assessment and constant feedback to foster personal development (Merino et al., 2022; Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). They provide psychosocial and emotional support through individualized guidance and follow-up to overcome personal and educational difficulties (Báez Garrido et al., 2006). They offer non-academic activities such as sports and art, which contribute to the development of social and emotional skills (Espinoza et al., 2019). Appendix 3 shows a table of factors that contribute to the success and failure of E2Cs, providing a clear picture of the elements that must be considered to improve the effectiveness of these programs.

E2C outcomes

E2Cs play a crucial role in the educational and social reintegration of young people who have dropped out of the formal education system because they contribute to the acquisition of personal, economic, training and vocational functions and have an impact on the competency development of their participants.

The categories in Table II on E2C outcomes were selected based on a qualitative analysis of the studies included in the ESR. These categories reflect the various areas in which E2Cs are present in the lives of young people, encompassing aspects of training, certification, professionalization, personal development, educational and workplace reintegration, socialization, support for the public, emotional aspects, employability, financial aspects, comprehensive guidance, self-knowledge, healthy habits, critical thinking and commitment to their future and education. These categories were selected by identifying the main findings and competencies developed by the students, as reported in the studies analyzed.

TABLE II. E2C outcomes by categories

| Categories | |

|---|---|

Training function or competency

|

|

| Certification/proof function or competency |

|

| Professionalization function or competency (preparation for adult life) |

|

Personal development and self-knowledge function or competency

(Flexibility, adaptability) |

|

| Return to education system and/or job placement function |

|

| Socialization function or competency |

|

| Support function or civic competency |

|

Emotional, psychological, or subsequent mentoring function or competency (creation of support networks) |

|

| Employability |

|

| Economic function |

|

| Comprehensive development or guidance |

|

| Self-knowledge competency |

|

| Healthy habits |

|

| Critical thinking |

|

| Commitment to their future and education |

|

Source: Compiled by the authors

E2Cs help their students acquire certain competencies and skills, making a significant positive impact on their lives, especially for those who have experienced school failure and social exclusion. These schools contribute to the youths’ development, addressing several key competencies. According to Palomares-Montero et al. (2024), 36.2% of the students significantly improve their basic skills, which allows them to progress in their education and increase their motivation to continue in the education system, thus facilitating school reintegration (Merino et al., 2022). They also provide certifications that are essential to enhance the students’ curriculum vitae and facilitate their access to the formal job market (Espinoza et al., 2018; Houot and Lavielle-Gutnik, 2023). E2Cs offer vocational training, preparing them for adult life through practical skills-building and internships at companies (Chisvert-Tarazona et al., 2024), which improves their professional skills (Palomares-Montero et al., 2024). These institutions also foster personal development and self-knowledge, providing flexible and personalized education that helps students boost their self-esteem and confidence (García-Rubio, 2023; Martínez-Morales et al., 2024) (Table II).

E2Cs facilitate the reintegration of young people into the education system or entry in the workplace, helping them to overcome absenteeism and improving their preparedness for the job market (Macedo and García-Rubio, 2022). They also contribute to the development of social skills and values, combating social exclusion and promoting the integration of young people into society (Pasternáková et al., 2023). In addition, these schools foster civic participation and critical reflection, which helps the youths to improve their surroundings and reduce economic and social inequality (Espinoza et al., 2018; Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). In this regard, they offer an emotionally supportive environment, contributing to the socio-emotional development of the students and ensuring their successful integration into the job market or the education system (Chisvert-Tarazona et al., 2024; Pasternáková et al., 2023). In terms of employability, E2Cs increase the young people’s job opportunities through the training received, job matching services and workplace internships (Pasternáková et al., 2023).

The certification earned at E2Cs is also crucial for access to formal jobs and improving living conditions (Espinoza et al., 2018). The programs promote overall student development, helping them to build a sustainable and fulfilling career (Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). Self-knowledge competency is a prominent area, given that E2Cs motivate students to make active decisions about their future and empower them to better adapt to diverse situations (Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). In terms of healthy habits, students improve their knowledge about health through leisure and sports activities (Báez Garrido et al., 2006; Merino et al., 2022). E2Cs also foster critical thinking and a commitment to the youths’ educational future, helping them to transform their surroundings and develop a greater sense of hope and responsibility for their lives (Espinoza et al., 2020; Moreno-Morilla and Romero-Rodríguez, 2024). In conclusion, E2Cs play a key role in the development of these youths’ academic, professional and personal competencies, offering them a second chance to build a more promising future.

Discussion and conclusions

E2Cs directly influence students’ lives, improving their personal and emotional development, helping them acquire skills and competencies, facilitating their inclusion in society and the workplace, promoting a return to education and fostering their active participation and empowerment. The references to the articles and authors mentioned above highlight the importance of a comprehensive, tailored approach that contributes to the success of these schools.

E2Cs not only have a positive and transformative impact on the young people, but they also afford a second chance to improve their education, personal development, employability and social integration. These programs are essential in helping young people overcome early school leaving and build a more promising future (European Commission, 2001; Eurostat, 2023; Soto et al., 2021).

While E2C students have a profile that commonly features socioeconomic vulnerability, prior educational difficulties, and in many cases, experiences of social and family exclusion, the interventions at these schools are geared towards providing them with a second chance to reintegrate into the education system and improve their employment and social prospects (Cimene et al., 2023, Know, 2020; Meryem et al. 2024).

In addition, E2Cs seek to tailor the students’ training paths through diagnostic assessments, continuous monitoring and the use of narrative tools that facilitate reflection on their own pasts and aspirations. Through continuous assessment and tailored mentoring, the training process can be adapted to match the progress and needs of each young person. This curricular flexibility, together with the collaboration with multidisciplinary services, ensures that each young person receives adequate support for their overall development, and these findings are also shown in the review conducted by Paniagua (2022).

E2Cs apply a variety of pedagogical approaches that promote active participation, tailored learning, integration of theory and practice and the development of socio- emotional skills, in order to offer students a true opportunity to reintegrate into the education and employment system.

In terms of the competencies they help the young people develop, the findings confirm that these schools have an impact not only when it comes to improving academic performance, but also with regard to the youths’ social, emotional and professional skills. E2Cs are designed to provide training that combines academic knowledge with practical vocational skills. The young people attending these schools typically have the opportunity to develop key competencies in both academic and professional fields, such as problem solving, critical thinking, time management, and technical and job skills (Bitsakos, 2021; Van Den Berghe et al., 2024).

The study by Gueta and Berkovich (2022) also confirms the findings of this review. E2Cs focus on the development of social and emotional skills, which are essential for the social and professional integration of young people. Students who have been exposed to complex family and social circumstances often benefit from this more comprehensive approach. Autonomy in learning and social and professional empowerment such as agency, trust and control over one’s professional and personal future are positive findings that have been addressed in the research analyzed.

However, it is also true that the few meta-analyses found that examine educational initiatives similar to E2C report both positive and negative findings. Paniagua (2022) offers a possible explanation for these differences: the pedagogical model of the schools works, but the methodological quality of the primary research from which the evidence is drawn is lacking.

In conclusion, this exploratory scoping review has made it possible to objectively assess the effectiveness of E2Cs by compiling and analyzing prior research, identifying whether these schools are actually fulfilling their purpose and pinpointing factors that contribute to their success or failure. The evidence shows that best practices and successful methodologies can be identified. Thus, evidence-based adjustments can be rendered in education policy and E2C leadership, which will improve the quality and impact of the programs offered. The study has aided in consolidating and disseminating knowledge on how E2Cs work. This type of review is not limited to mere data compilation, but also helps to integrate different perspectives and approaches that may have been overlooked in separate studies. The findings presented here enrich the overall understanding of the E2C pedagogical model

However, the results obtained must be treated with a degree of caution. The number of papers that met the inclusion criteria is limited, and the methodological quality is not always rigorous. An effort was made to compensate for this limitation through a detailed analysis of each study, so that itemized information is offered on the programs and their effects. The scarcity of meta-analyses on educational reintegration programs shows the need for an increase in primary research with methodological quality.

- Non-formal education programs can play a crucial role when it comes to providing a second chance at education for children and youths that do not attend school, thus expanding the educational opportunities to include programs that are out of reach in the traditional public school system. However, these educational opportunities must provide a recognized path toward the formal education system.

- States need “second chance” systems and programs that re-engage and redirect young people who drop out of the public school system. Although the body of research on the effectiveness of such programs is rather limited, most of the findings are positive. The individual and societal cost of neglecting this problem is potentially enormous for countries.

- There is a need to further consolidate the ties between universities and E2Cs through innovation and research projects: universities could provide support in the evaluation of the E2C model while the schools could contribute their professional experience of working with disadvantaged, unqualified, unemployed youths at risk of social exclusion.

- Educational disadvantage stems not only from a lack of financial resources. It can also be the result of a lack of “useful” socio-cultural resources, as well as inequalities associated with marginal social status. In order to understand educational disadvantage, it is therefore necessary to analyze both the social status of individuals and the social arrangements of society.

- The opportunities offered should not be limited to providing equality. The means for achieving goals (resources) differ from the freedom to achieve goals (capability); the latter affords genuine opportunities to be and do what the individual values. Policy provisions should be assessed not only in terms of the resources that are allocated to address unfair inequalities, but also in terms of the extent to which the opportunities are adequate, relevant and convertible.

- Differences in educational outcomes alone do not provide a full picture. It is important to bear in mind the opportunities these young people have received, as well as the factors that may have prevented them from taking advantage of those opportunities and turning them into meaningful achievements.

Acknowledgements

This study is a collaboration funded by E2O and XXX (Article XXX).

Appendix 1. Assessment of the methodological quality of the primary research

Appendix 1. Assessment of the methodological quality of the primary research

Appendix 3. Related factors that contribute to the success and failure of E2Cs

Factors linked to success

Factors linked to failure

Personalization of training paths

Lack of financial and material resources

Adapting to the students’ individual needs

Discouragement and prior low academic performance

Ongoing, non-punitive assessment

Behavioral problems and criminal conduct

Psychosocial and emotional support

Dysfunctional family backgrounds

Collaboration with multidisciplinary services

Lack of follow-up and job orientation

Dual vocational education and training (VET)

Disinterest in school stemming from negative

experiences

Active participation and practice-based learning

Social stigmatization and exclusion

Family involvement

Addiction issues

Development of social and emotional skills

Lack of integration in the traditional education

system

Educational certification and job preparedness

Lack of job opportunities

Notes

Referencias bibliográficas

Barrientos, A. (2022). Revisión crítica de la historia y

desarrollo de la educación alternativa y las escuelas de segunda

oportunidad.

Bernard, P.Y., & Michaut, C. (2021). Expériences et motifs

de décrochage scolaire: entre rejet de l’école et quête du travail

rémunéré.

Bingham, A.J., & Witkowsky, P. (2022). Deductive and

inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. En C. Vanover et

al. (Eds.)

Bitsakos, N. (2021). An Evaluation of Second Chance Schools in

Greece: A National Survey of Educators´ Perceptions.

Bramer, W.M., Rethlefsen, M.L., & Kleijnen, J. et al.

(2017). Optimal database combinations for literature searches in

systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study.

Cimene, F.T. et al. (2023). Understanding the Complex Factors

behind Students Dropping Out of School.

Contreras-Villalobos, T., López, V., Baleriola, E., &

González, l. (2023). Dropout in youth and adult education: a

multilevel analysis of students and schools in Chile.

Cooper, C., Booth, A., & Varley-Campbell, J. et al. (2018).

Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a

literature review of guidance and supporting studies.

European Commission (2001).

European Commission (2022).

Eurostat (2023).

Espinoza, Ó., Castillo, D., González, L.E., Santa Cruz, E.,

& Loyola, J. (2014). Deserción escolar en Chile: un estudio de

caso en relación a factores intraescolares.

Gueta, B., & Berkovich, I. (2022). The effect of

autonomy-supportive climate in a second chance programme for at-risk

youth on dropout risk: the mediating role of adolescents’ sense of

authenticity.

Gusenbauer, M., & Haddaway, N. (2020). Which academic

search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses?

Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other

resources.

Higgins, J.P.T. et al. (2022) (Eds.).

Kwon, T. (2020). Social stigma, ego-resilience, and depressive

symptoms in adolescent school dropouts.

Martínez-Valdivia, E., & Burgos-Garcia, A. (2020). Academic

Causes of School Failure in Secondary Education in Spain: The Voice of

the Protagonists.

Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for Conducting a

Scoping Review.

Meryem, H., Khabbache, H., & Ait Ali, D. (2024). Dropping

out of school: A psychosocial approach.

Ministerio de Educación y Formación profesional (2023).

O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2008). The

quality of mixed methods studies in health services research.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2012). Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en

Page, M.J. et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement.

Paniagua, A. (2022).

Philip, D. (2000). The Relevance of Systematic Reviews to

Educational Policy and Practice.

Pong, S.L., & Ju, D.B. (2000). The Effects of Change in

Family Structure and Income on Dropping Out of Middle and High School.

Sánchez-Martín, M., Pedreño Plana, M., Ponce Gea, A.I., &

Navarro-Mateu, F. (2023). And, at first, it was the research question…

The PICO, PECO, SPIDER and FINER formats.

Soto, A.B., González-Gijón, G., & Díaz, A.S. (2021).

Alternative education and second chance schools: Global and Latin

American perspectives on its history and Outlook.

Sterne et al. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk

of bias in randomised trials.

UNESCO (2009). Experiencias educativas de segunda oportunidad. Lecciones desde la práctica innovadora en América Latina. UNESCO.

UNESCO (2014).

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated

Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item

checklist for interviews and focus groups.

Torkashvand, M., Pourrahimi, M., Jalilvand, H., Abdi, M.,

Nasiri, E., & Haghi, F. (2022). Factors Affecting Academic Failure

from Students’ Perspectives.

Van Den Berghe, L., De Clercq, L., De Pauw, S., &

Vandevelde, S. (2024). The roles Second Chance Education can play as a

learning environment: A qualitative study of ‘drop-in’students.