Socio-educational strategies and benefits in Basic Vocational Education and Training: The case of the Basque Country

Estrategias socioeducativas y beneficios en la FPB: el caso del País Vasco

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-690

Andoni Piñero Pradera

Universidad de Deusto

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2169-0659

Janire Fonseca Peso

Universidad de Deusto

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9539-4687

Álvaro Moro Inchaurtieta

Universidad de Deusto

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0167-6048

Abstract

This article seeks to identify the benefits derived from students’ experiences in Basic Vocational Education and Training (Basic VET) and to analyse the socio-educational strategies that make it possible to attain these benefits. The study draws on the perspectives of 132 people (students, family members, educational staff, and leadership teams) collected through 17 focus groups (six face-to-face and 11 online) in 12 centres across the Basque Country. The results show that students’ experiences are not only limited to academic gains but also influence personal and familial domains, as well as relationships with peers and other adults. By creating positive experiences, the educational team fosters an environment where students and their families feel protected and welcomed. The results of this research underscore the importance of training in socio-educational strategies for future education professionals, particularly in Basic VET.

Keywords:

basic vocational education and training, early school leaving, social inclusion, teaching staff, families

Resumen

El presente artículo busca identificar beneficios de la experiencia como estudiante en la Formación Profesional Básica (FPB), así como analizar las estrategias socioeducativas que permiten alcanzar dichos beneficios. Se han analizado los discursos de 132 personas (estudiantado, familiares, equipo educativo y directivos) a través de 17 grupos de discusión (6 presencial y 11 online) en 12 centros del País Vasco. Los resultados muestran cómo la experiencia no sólo se limita a beneficios académicos, sino que trasciende a ámbitos personales, familiares, de iguales y de relación con otras personas adultas. Esto es posible debido al diseño de experiencias positivas por parte del equipo educativo que generan entornos donde el estudiantado y sus familias se sienten protegidos y “re-cogidos”. Los resultados de esta investigación profundizan en la importancia de la formación en estrategias socioeducativas de futuros profesionales de la educación, especialmente de la FPB.

Palabras clave:

Formación Profesional Básica, Abandono Escolar, Inclusión social, profesorado, familiasIntroduction

Unlike the early 20th century, when attending school almost always guaranteed employment and social integration, today it primarily serves to acquire core citizenship competences and basic training to be able to pursue different specialised pathways. The experience and development of these citizenship competences may be hindered depending on students’ engagement with the training offered, which is conditioned by the prevailing educational models in schools (Tarabini et al., 2019). In this regard, the proliferation of international studies on early school leaving highlights the challenge faced by the current education system to guarantee quality and equal opportunities for learning and growth. The phenomena of school failure and early school leaving are influenced by multiple factors, including endogenous dimensions (personal and relational) and exogenous (structural and institutional) (Romero & Hernández, 2019, p. 268), which hamper personal and professional development in terms of access and participation, as well as impeding social mobility (Morentin-Encina & Ballesteros, 2020; Santibáñez et al., 2024). In Spain, the percentage of early school leavers in 2023 was 13.6%. While the data has been improving over the years (down 0.3 percentage points compared to 2022, at 13.9%, and 10.0 points compared to 2013), and the gap with the EU has also been decreasing (4% in 2022) (Ministerio de Educación, Formación Profesional y Deporte del Gobierno de España, 2024), the education system continues to implement reforms and modifications in education to mitigate early school leaving.

Since the 1980s, various laws have been passed with each proposing different programmes that seek to alleviate the issue of early school leaving and school failure in diverse ways: from the Social Guarantee Programmes, which were replaced by the Initial Vocational Qualification Programmes and later by Basic Vocational Education and Training (Basic VET) or Basic Level in Vocational Training. These legislative changes are aimed at improving the educational needs of the most vulnerable groups in order to avoid potential segregation. Concerning VET, a notable milestone of the current Spanish education law, LOMLOE, was its incorporation into the general education system, which in turn allowed for specific adjustments and adaptations to VET (Santibáñez et al., 2024). However, the recent report published by EUROCHILD (2024) reminds us that these measures are still ineffective.

As described in previous works (Piñero et al., 2024), Basic Vocational Education and Training (Basic VET) programmes are designed for students between 15 and 17 years of age who, having completed the third year of Compulsory Secondary Education or, in exceptional cases, the second year, are at risk of school failure or have already failed. These programmes are developed over two academic years and are aimed at those students who have not yet completed Lower Secondary Education and wish to continue their compulsory education free of charge. At the end of this programme, students can obtain the Basic Professional Technician certificate, which facilitates access to intermediate vocational training. Moreover, by taking the final assessment test, they also have the chance to obtain the Compulsory Secondary School qualification, which allows them to continue in the education system and return to it at the end of the programme (Aramendi & Etxeberria, 2021; EUSTAT, 2024; Sarceda-Gorgoso & Barreira-Cerqueiras, 2021).

The purpose of these models is to rethink the curricula that cater to

this diverse population that has been left out of the mainstream

education system, addressing issues related to the inequality or

discrimination they suffer in their educational pathway, seeking to

overcome the individualistic perspective rooted in school failure, which

reflects a

A number of VET students are characterised by their negative educational experiences, high levels of demotivation, low self-esteem, aversion to learning, insecure behaviour and, in some cases, non-cohesive family environments (Fundación Tomillo, 2022). Similarly, there is a problematic use of free time, issues with discipline, emotional and social deficiencies (Aramendi et al., 2022), isolation, and low job expectations and lack of opportunities (Fernández-García et al., 2019), all of which ultimately have an impact on access to rights such as employment and housing (Martínez-Carmona et al., 2024; Sarceda-Gorgoso et al., 2017).

Given that several studies have underlined the key role teachers play in students’ academic school success and social inclusion (Aramendi et al., 2022; Aramendi & Etxebarria, 2021; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Miesera & Gebhardt, 2018; Van Middelkoop et al, 2017; Viniegra-Velazquez, 2021), it is essential to address the evolving professional profile that is required to ensure that the change in the methodological paradigm, which is more focused on socio-emotional and competence development (Sánchez-Bolívar et al., 2023), is real and successful. In this sense, teachers who are sensitive to diversity (Aramendi et al., 2018) act as a safeguard by motivating learners to study, building relationships of closeness and trust with students, fostering confidence, and facilitating the possibility of family commitment and engagement (Salvà et al., 2024). The recent CaixaBank report on dropout in VET (Salvà et al., 2024) includes various studies that confirm and support this idea. Thus, when there are opportunities to develop positive relationships between teachers and students, and among peers, the feeling of belonging and commitment to school increases, both inside and outside the centre (Salvà et al., 2024). In turn, there is a direct relationship between students´ social skills and their commitment to the educational system when there are opportunities for joint student-teacher participation and involvement in issues related to the school´s daily life (Salvà et al., 2024). Maintaining such a professional role can take an emotional toll on the educational team (Fix et al., 2020), even more so when the context lacks the necessary support or resources (Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023).

It is imperative to coordinate the various agents involved, since the three systems, family, peers and educational, foster students’ self-concept as a mediating variable, which subsequently has a direct impact on school engagement (Ramos-Díaz et al., 2016, p.349). From a systemic perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1992), the school´s responsibility extends beyond the microsystem, incorporating elements belonging to the mesosystem, in order to improve the students’ interactions with their closest environment, especially with their families (Sureda-García et al., 2021). Research has shown that positive collaboration between schools and families has a direct impact not only on students´ academic achievements at an emotional and social level, particularly in those who may be in a situation of social exclusion (Gálvez, 2020), but also on the improvement of skills, school engagement, and student behaviour in terms of prosocial behaviour and emotional regulation (Antelm-Lanzat et al., 2018). Various studies point to the importance of providing families with the chance to become highly involved and participants, given its effects on factors such as early school leaving and better academic performance (Hernández-Prados et al., 2023).

Method

This article seeks to identify the benefits derived from students’ experiences in Basic VET and to analyse the socio-educational strategies that make it possible to attain these benefits. The research questions that have guided the analysis have been the following: What benefits are perceived by the different agents involved in the Basic VET model, and how do they experience these benefits? What happens within these spaces? How are different situations addressed? The aim is to contribute to current debates on socio-educational practices in the context of Basic VET.

A qualitative approach was selected because of its comprehensive nature, which offers a set of tools and perspectives that are fundamental to gaining insight into the complexity of social phenomena. Conceptualising and exploring phenomena such as positive experiences requires an approach that captures the richness of narratives and interactions, and the process of category description emerges as an essential tool for organising and analysing qualitative data in a systematic way (Flick, 2014).

Sample

A convenience sample was collected from the VET centres invited to take part once the project had been explained. The decision to use a convenience sample in the selection of the participating VET Centres was based on practical and logistical considerations. Due to the exploratory nature of the study and its objective to gain an in-depth understanding of the dynamics and benefits experienced by the different educational agents in VET, priority was given to accessing centres that were willing to participate and reflected the territorial diversity of the Basque Country (Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, and Araba).

Recognising the limitations of convenience sampling, this approach allowed for the inclusion of a variety of perspectives from students, families, teaching staff, and leadership teams, thus enriching the data collected. The groups provided a setting for generating rich and detailed data, which contributes to a deeper understanding of the subject. As highlighted by Morgan (1997), group interaction in focus groups facilitates access to the complexity of opinions and experiences, even when the sample is non-probabilistic.

The sample was selected according to territorial criteria (three provinces) and the inclusion of educational actors in Basic VET programmes (students, families, teaching staff, and leadership teams). Thus, there were seven groups of students (three in Bizkaia, two in Gipuzkoa and two in Araba), six groups with families (two in Bizkaia, two in Gipuzkoa, and two in Araba), three groups of teaching staff (one per province), and a group made up of members of leadership teams from all over the Basque Country. In total, 17 focus groups were held (six face-to-face and 11 online) in 12 centres in the Basque Country. Specifically, a total of 132 individuals participated.

Instrument

Focus groups were used to obtain detailed information about participants´ experiences, perceptions, and opinions (Barbour, 2011). The choice of the focus group methodology was primarily to promote interaction between participants, not only to gain a more complete understanding of good practice by contrasting different points of view, but also to identify shared definitions of what constitutes good practice in vocational education and training, as well as gathering new ideas and perspectives that emerged from the collective dialogue.

Focus groups stand out as spaces where interaction and dialogue allow access to the social construction of meanings. Guided by a moderator, these groups generate data by collectively exploring a topic, and their validity depends on careful planning, effective moderation, and a rigorous analysis of the information produced (Krueger & Casey, 2014). Thus, by bringing together those directly involved in VET (students, teaching staff, leadership teams, and families), the focus groups provided an authentic and contextualised view of good practices from different discursive positions (Burguera-Condón et al., 2021), which contributed to obtaining results applicable to the real context of VET, in addition to pinpointing concrete strategies that were perceived as effective by the participants themselves.

The focus groups were carried out between January and May 2023, with the face-to-face groups conducted in the centres, while the online groups were used for participants from other centres. The sessions were recorded, prior to which participants were explained the purpose of the study and the conditions of participation, along with the ethical considerations related to confidentiality and data protection. After they had accepted and signed the informed consent form, the sessions were carried out, with the research team taking field notes throughout this process. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Deusto (Ref:). ETK-51/21-22.

Procedure

The analysis presented here is based on the transcripts of the focus group recordings (17h and 30 min of audio), as well as the field notes taken by the research staff. To preserve confidentiality, testimonies are identified by initials.

All the material collected during the fieldwork was processed with

the qualitative analysis programme

Finally, the analysis focused on the most relevant categories within the dimensions studied: a) perceived academic and personal benefits or those associated with peers and family members; and b) socio-educational strategies inside and outside the classroom.

TABLE I. Main Categories and Subcategories of Analysis

| Main Category | Subcategory | Approach | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Benefits | Academic | Etic | Improvements in performance and skills acquisition. |

| Personal | Emic | Promotion of self-concept and self-esteem. | |

| Socio-Educational Strategies | Welcoming | Emic/Etic | Creation of a supportive and safe environment. |

| Flexibility | Etic | Adaptation of educational practices to the needs of students. | |

| Communication with Families | Emic | Development of collaborative relationships with families. |

Source: Compiled by the authors

The analysis of the qualitative data was undertaken through an

iterative process combining

This process of triangulation between theory and participants´ voices strengthened the validity of the findings and contributed to a deeper understanding of socio-educational dynamics in Basic VET.

Limitations

Although this study provides valuable information on socio-educational experiences and strategies in Basic VET within the specific context of the Basque Country, there are certain limitations when it comes to generalising the results directly to other contexts. At the outset, it should be noted that in the qualitative approach, the sample is not necessarily defined in terms of statistical representativeness but rather as a strategic selection of participants or informants who can provide valuable insights and richness to the data (Patton, 2015). Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted within the limits of its specific context and with caution when extrapolating them to other educational settings. Factors such as regional education policies, the socio-economic characteristics of the student population, and the cultural particularities of each educational institution may influence the implementation and outcomes of socio-educational strategies.

In future research, it would be beneficial to explore the possibility of using probability samples that allow for greater generalisation of the results. Similarly, comparative studies between different regions or countries could provide richer insights by identifying similarities and differences in socio-educational practices and their impact on Basic VET students.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable and in-depth knowledge on effective socio-educational strategies within the context of Basic VET in the Basque Country, which was the focus of the research funding, and can serve as a basis for developing more informed educational interventions and policies.

Results

This section is divided into two parts: benefits and socio-educational strategies conducive to achieving these benefits.

Benefits Derived from the Training Experience in Basic VET Centres

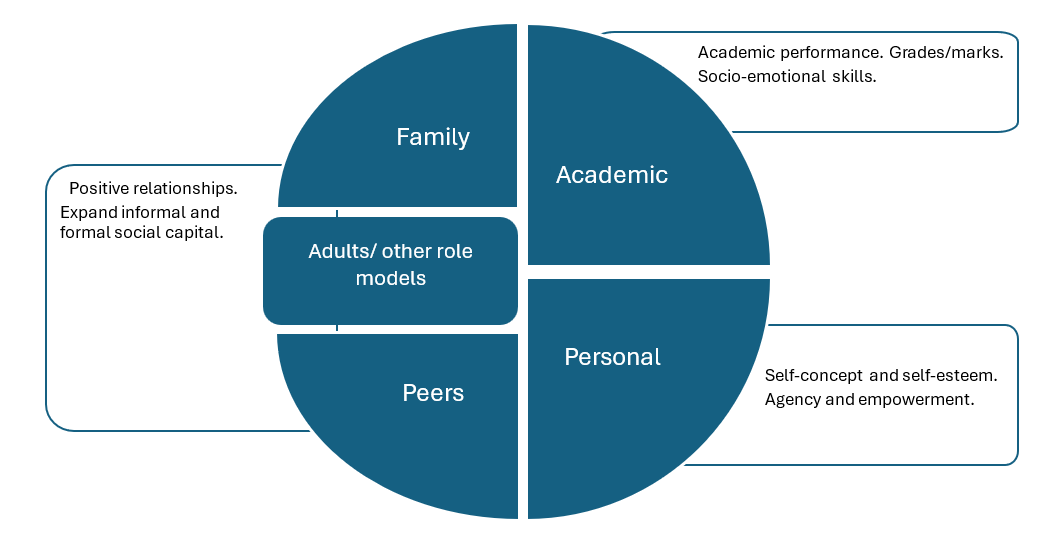

The analysis of the testimonies of the different groups, namely, the students, their families, the teaching staff, and leadership teams, point to the fact that socio-educational intervention in this context goes beyond improving academic performance. They highlight four major areas that, following the systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1992), are mutually reinforcing: academic, personal, reference adults, peers, and family. It is therefore regarded as a multidimensional, multifaceted, and holistic field of socio-educational intervention (Aramendi et al., 2022; Aramendi & Etxebarria, 2021; Echeita, 2019).

FIGURE I. Benefits derived from the training experience in Basic VET centres

Source: Compiled by the authors

In terms of academic benefits, while there is a debate about whether the demands are the same in comparison with formal education, it is widely agreed that grades/marks improve. Moreover, beyond the quantitative assessment itself, students gain socio-emotional skills that improve not only their technical level, but also school dynamics and the teaching-learning process (Sánchez-Bolívar et al., 2023). At the same time, objectively, it is observed that they begin to pass subjects and obtain high marks, which seems to positively influence their self-perception as students.

However, in addition to academic benefits, all the groups, notably students and families, underline the personal impact. They are struck by the way in which the group of educators positions itself in relation to the group of students and their realities. When exploring the underlying reasons, the discourses reveal essential factors that contribute to a perceived improvement at a personal and systemic level. These include administrative irregularities, family and/or peer conflicts, as well as problems related to substance abuse and other addictions. The responses observed are adjusted to the students’ needs, taking into account the systems that interact in their lives. What they highlight most is their feeling of "becoming more mature", in the sense of promoting development of agency ("I am capable, I have resources, and if I do not, I am capable of looking for alternatives"), participation, and empowerment ("my opinion matters, as do my actions, and my actions can have an impact at the community level"), consequently leading to greater well-being during a vulnerable and formative stage of life (Piñero et al., 2024).

The group of Basic VET students largely come from contexts where

school authority figures in hierarchical positions, through their

discourse and behaviour, assigned them negative

Similarly, family relationships tend to improve, which could be attributed to the positive feelings perceived in the aforementioned systems; they feel "less on guard" and "safer", due to the two-way relationship created by the school, marked by closeness, flexibility, accessibility and opportunities for involvement. The family´s own support, and the support of their peers, foster students´ self-concept, improving their academic performance and well-being (Ramos-Diaz et al., 2016).

Acknowledging the idea that well-designed and well-organised Basic VET is a guarantee of social and labour market insertion (Aramendi et al., 2018) for an at-risk group that could end up increasing the percentage of the population with difficulties and even the number of people at risk of social exclusion, brings to the fore the need to delve deeper into the successful socio-educational methodologies, methods, and strategies being implemented on a daily basis by professionals in their centres and the community. How are the previously mentioned benefits achieved? In other words, what underlies the success of this model?

Socio-educational strategies to promote protective educational spaces

This research is grounded in the approach that citizenship, both the

experience and construction of it, which is a holistic experience,

understood as an educational process that accompanies individuals

throughout their life course, encompasses formal, non-formal, and

informal education, transcending the standardised and formal curriculum

(Gil-Jaurena et al., 2016). Today, although we are witnessing a

neoliberal wave across the globe, international organisations such as

the United Nations and the Council of Europe continue to advocate for

democratic societies. This approach to fairer and more democratic

societies draws on the Aristotelian conception of the individual as a

free and autonomous citizen, freedom being the fundamental principle of

democracy. Based on Arendt´s thesis on freedom and responsibility

(Arendt, 1997), in which both are deemed essential aspects to the human

condition, it seems pertinent to consider the appropriateness of the

concept

Engagement is part of a process related to factors such as interest in the subject and decision-making capacity. The starting point can be found in the curricular structure defined by legislation. Specifically, in the composition of theoretical class hours and practical class hours, the latter of which is carried out through workshops where they develop and improve the skills necessary for entering the labour market. This particular structure is highly valued by all the agents in the focus groups as it fosters an intrinsic motivation to participate because they find meaning in what they do and feel useful. From a pedagogical point of view, this resource is used as a way of creating a link with the theoretical classes, both in terms of content and training to develop responsibility. They are thus committed to the comprehensive development of students (Aramendi &Etxebarria, 2021), with the goal of increasing the personal and social resources needed to succeed in society.

There is also an emotional component mediated by the desire to belong to a group (Pahl, 2019). Upon entering the classroom, the teacher disregards the classic structure. The first step is to ignite and sustain the students’ motivation, which they do through emotional connection and bonding. By implementing this strategy, they seek to create a meeting space where individuals feel comfortable, allowing relationships of trust to be built among peers and with adults, which is crucial for participation and engagement (Fonseca & Maiztegui-Oñate, 2017). In terms of content, although they have a curriculum that serves as a guideline, it is not the primary focus; instead, they first take into account the interests of the group through symbolic and critical paradigms, collaboratively building from that base. In this process, the closer they get to the students’ realities, the greater their success.

Interest in the subject, motivation to attend, and continued engagement with the centre primarily depends on the willingness of the teaching staff to build an ongoing relationship, where the task itself is not the final objective, but rather respecting a student’s time, listening, and proposing any topics without judgement are prioritised (Fonseca, et al., 2023). This approach involves personal and individualised support for learning, where educators conduct diagnostic assessments (through tutorials, observation, and coordination) to enhance the skills of each student.

The intervention also includes a community component. In the learning spaces, students are positioned as sources of knowledge, with collaborative methodologies employed so that the experience is shared, and participation is put into practice through actions that allow them to have a voice. In this way, the true act of teaching, as advocated by Freire (2010), is approached, where the act of apprehending the content or cognitive object requires a prior or simultaneous process, with which the learner also becomes a producer of the knowledge that was taught (p.143).

While it is true that knowledge is assessed in the same way as in secondary education, it seems that the level of rigour is lower, placing greater emphasis on other acquired skills. This type of assessment has led to controversy among professionals. For some, this "discredits" the Basic VET model. For others, and in line with the findings of Sureda-García, et al. (2021), the fact of focusing less on their weaker competences and prioritising others, encouraging and guiding them on what to do and how to develop the desired skills, facilitates the attainment of valuable behavioural, attitudinal, and cognitive outcomes.

Coordination between the educational team and the support provided by

the leadership team is a key strategy to ensure that the idea of

flexibility does not equate to "loss of control". In fact,

flexibility is more aligned with authority than with a lack of

authoritarianism since, from a horizontal position, it seeks to

accompany, guide, and draw out students’ inner capacities, encouraging

them towards their fulfilment (Viniegra-Velázquez, 2021). Furthermore,

it involves consistent accompaniment through appropriate guidance,

general support, positive messages, and setting boundaries, if

necessary, which fosters not only a sense of psychological and emotional

security but also a respectful and welcoming environment based on

relationships of trust and support (Fonseca et al., 2023). Firstly,

adults serve as a guarantee of protection, taking care of them, watching

over them, and ensuring that possible problems that may arise between

peers are solved peacefully. In terms of emotional security, the

students point out that it is a space where they can be themselves

without fearing the reaction of adults and peers. These are processes

where students put themselves to the test, assessing the reach of

educators, within a preconceived framework of their relationships with

key adult figures. The process, the duration of which can be longer or

shorter depending on the students’ background, takes on a more

"peaceful" aura when they encounter responses that are

different from what they are used to. They become aware of their new

relationship, feeling that "they are not enemies", and that

they will not be abandoned, allowing them to break free from old

patterns. They mention the feeling of tranquillity when they work on

personal or social aspects because they feel that they are listened to

and respected. This study supports findings from previous research

(Salvà et al., 2024) that illustrates that communication, emotional

support, and the bond between teachers and students, characterised by

these positive, close interactions and what is referred to as

Creating environments in which individuals can engage and take part, within a context of clearly established rules and boundaries, while fostering horizontal relationships, allows others to feel they are part of something (Fonseca et al., 2023).

Providing support and accompaniment on a daily basis can lead to

personal satisfaction if successful processes are eventually seen.

However, throughout this process, the narratives of the group of

educators and the leadership team underline difficulties and problems

that directly impact the psycho-emotional well-being of the

professionals. Similar findings were reported by Fix et al. (2020),

pointing out that teachers´ own involvement evokes strong emotions such

as satisfaction and pride, but also frustration and doubt, which may

trigger burnout, as the sustainability of their performance influences

their well-being and emotions. This situation is further aggravated if

we take into account the legal and administrative requirements to be

hired in this field: some teachers have a high level of technical

qualifications, yet are

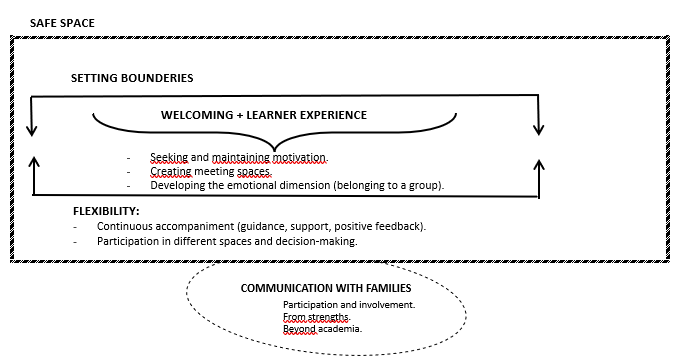

The set of strategies analysed so far gives a glimpse of a safe environment, characterised by a combination of a welcoming approach, flexibility, and boundaries (Figure II). Such an environment allows students to reintegrate into their educational pathway, leaving behind the negative experiences and obstacles they had previously encountered.

FIGURE II. Socio-Educational Strategies to Promote Safe Educational Spaces

Source:

Compiled by the authors

Source:

Compiled by the authors

Voluntary identification with the group and the environment leads to assuming responsibilities (Fonseca et al., 2023). Previous studies show how the active participation of students positively influences learning processes and academic success, acting as a protective factor against early school leaving. In turn, this type of support is reminiscent of an intervention based on the capabilities approach (Sen, 2000): one that is centred on agency, by acting or exerting influence and power in a given situation; centred on competence, by developing new skills and being appreciated for the talent one has or has acquired; and centred on belonging, by developing meaningful relationships with peers and teachers, giving them an active role in the school.

The educational teams are aware that their intervention in the centre will be more successful if they get the external environment involved, generating a butterfly effect by setting in motion mechanisms that, with the proper support, start to fit together. Thus, communication with families is another fundamental strategy in the socio-educational process (Figure II), aimed at improving interactions and coexistence (Sureda-García et al., 2021). The families and the group of students value the ongoing contact positively, without perceiving any kind of negative judgement or fear when it comes to communication between their educational reference figures.

What makes this communication successful is the approach taken to foster it. Family members feel that they are not only listened to but also actively sought out and invited to join in, to get involved and take part in the process. This type of listening goes beyond academic situations and also addresses the family´s own needs (sometimes explicitly, other times implicitly) through guidance sessions (face-to-face or by telephone) or referrals.

Moreover, the relationship is established from the point of view of strengths rather than from a perspective centred on "deficit". This seems to be what makes the difference. According to the testimonies, prior to entering Basic VET, most of the families experienced a profound sense of hopelessness because of their children´s behaviour, the messages received from the educational figures, and their own feelings of inadequacy and guilt as parents. But they were surprised to find another profile among the teaching staff at Basic VET, who invited them to become involved in a socio-educational process based on respect and on communicating positive feedback, both about their children and about themselves. In essence, this approach to family education allows families to rebuild their self-concept and to re-conceptualise their role as educational agents in collaboration with the centre. They begin to change the image they have of their children, leading to a more amicable way of relating to each other. Their sons and daughters perceive this shift, and the Pygmalion effect is redirected towards a focus on goals and achievements.

Conclusions

This article has identified the benefits derived from the student experience in Basic VET and analysed the socio-educational strategies that make such benefits possible. The findings demonstrate how Basic VET centres can be structured around concrete practices, with adults playing a fundamental role in creating environments where students and their families feel protected and welcomed. This is especially crucial for those students in the Spanish education system who experience high levels of school failure and, in some cases, behavioural problems (Hernangómez & García, 2023). These centres appear to be more than merely instruments for obtaining the basic skills needed to enter the labour market; they also serve as spaces for coexistence and education, in its broadest sense, where students have the chance to redefine their educational experience, becoming a person with a better self-concept and full capacities for inclusion and comprehensive development within society.

These are spaces for coexistence where teachers who are actively

involved support students and have an impact on their socio-educational

competences. This path is also shared with the families, making them

accomplices in the socio-educational process, offering them an image of

their children that differs from the one given at school, as well as

insights and spaces to relearn how to interact with them. It is about

teachers who constantly question their practice, who

In light of the fact that teachers should be trained in pedagogical strategies that accompany students in the socio-educational process, a greater emphasis needs to be placed on developing inclusive pedagogical skills, beyond the aforementioned mere teaching of content, focusing on teachers’ pedagogical practices with students (Miesera & Gebhardt, 2018). In the case of the Basque Country, there are authors (Aramendi & Etxebarria, 2021) who underscore the importance of improved teacher training for professional development in this area, given the demands of the current context of a diverse student body with risk factors; an educational challenge that merits future research. Addressing these issues allows us to create socio-educational intervention models that foster high standards of professional performance and support the emotional well-being of those working in the field. The findings of this research could play a key role in contributing to the training of future education professionals, particularly in the area of Basic VET.

Acknowledgements and funding

This article was carried out within the framework of the R&D&I research project EduRisk focused on best practices with at-risk youth in Basic Vocational Education and Training. Ministry of Science and Innovation – AEI with the reference PROYECTO/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Referencias bibliográficas

Alvarado Solis, E. (2023). Análisis fenomenológico de las

experiencias del docente-investigador de posgrado de la FES Aragón UNAM:

uso de las TIC en pandemia-pospandemia

Antelm Lanzat, A. M., Gil López, A. J., Cacheiro González, M. L.,

& Pérez Navío, E. (2018). Causas del fracaso escolar: Un análisis

desde la perspectiva del profesorado y del alumnado.

Aramendi Jáuregui , P., Cruz Iglesias, E., Altuna Urdin, J., &

Luzarraga Martín, J. M. (2022). Sensibilización docente y atención a la

diversidad en la Formación Profesional Básica: Cooperar para incluir.

Aramendi Jáuregui, P., & Etxebarria Murgiondo, J. (2021).

Construcción y validación del cuestionario para la medición del

compromiso hacia la atención a la diversidad en la Formación Profesional

Básica (COMAD).

Aramendi, P., Lizasoain, L., & Lukas, J. F. (2018). Organización

y funcionamiento de los centros educativos de Formación Profesional

Básica.

Arendt, A. (1997):

Barbour, R. (2011).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological theory system. En R. Vasta

(Ed.),

Bryman, A. (2012).

Burguera-Condón, J.L., Virgós-Sánchez, M., & Pérez-Herrero, M.D.

(2021). La Formación Profesional Dual en la empresa desde la perspectiva

de sus protagonistas.

Echeita, G. (2019).

EUROCHILD (2024). Children´s reality in Europe: Progress,& Gaps.

Available from:

EUSTAT. (2024).

Fernández-García, A.; García Llamas, J. L,. & García Pérez, M.

(2019). «La formación profesional básica, una alternativa para atender

las necesidades educativas de los jóvenes en riesgo social».

Fix, M., Ritzen, H., Kuiper, W., & Pieters, J. (2020). Make my

day! Teachers; experienced emotions in their pedagogical work with

disengaged students.

Flick, U. (2014).

Freire, P. (2010).

Fonseca, J., & Maiztegui, C. (2017). “Elementos facilitadores y

barreras para la participación: Un estudio de caso con población

adolescente.”

Fonseca, J., Maiztegui, C., & Santibáñez, R. (2023).

Socio-educational support in exercising citizenship: analysis of an out

of-school programme with adolescents,

Fundación Tomillo (2022).

Gagnon, N., & Dubeau, A. (2023). Building and Maintaining

Self‑Efficacy Beliefs: A Study of Entry‑Level Vocational Education and

Training Teachers.

Gálvez, I.E. (2020). La colaboración familia-escuela: revisión de una

década de literatura empírica en España (2010-2019).

Gil-Jaurena, I., Ballesteros, B., Mata, P., & Sánchez-Melero, H.

(2016). Ciudadanías: significados y experiencias. Aprendizajes desde la

investigación.

Hernández-Prados, M. Ángeles, Álvarez Muñoz, J. S., & Gil

Noguera, J. A. (2023). Percepción familiar de las tareas escolares en

función del rendimiento académico.

Hernangómez Criado, I., & García Yelo, Blanca A. (2023) Ejemplo

de situación de aprendizaje en formación profesional básica: la

geografía en la vida cotidiana Supervisión 21.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014).

Martínez-Carmona, M.J.; García-Segura, S., & Gil-del-Pino, C.

(2024). Antecedentes de la formación profesional básica como medida de

inclusión social.

Ministerio de Educación, Formación Profesional, & Deporte (2024). Explotación de variables educativas de la encuesta de la población activa año 2023. Subdirección general de estadística y estudios. Gobierno de España.

Miesera, S., & Gebhardt, M. (2018). Inclusive vocational schools

in Canada and Germany. A comparison of vocational pre-service teachers′

attitudes, self-efficacy and experiences towards inclusive education.

Morentin-Encina, J. & Ballesteros Velázquez, (2020). Tanto por

cierto: análisis de la medida del abandono temprano de la educación y

formación.

Morgan, D. L. (1997).

Pahl, K. (2019). “Recognizing Young People’s Civic Engagement Practices: Re-Thinking

Patton, M. Q. (2015).

Piñero Pradera, A., Pérez-Hoyos, J., & Moro Inchaurtieta, A.

(2024). La influencia de la participación en una vida plena y

satisfactoria del alumnado de formación profesional básica en el País

Vasco.

Ramos-Díaz, E., Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Fernández-Zabala, A.,

Revuelta, L., & Zuazagoitia, A. (2016). Apoyo social percibido,

autoconcepto e implicación escolar de estudiantes adolescentes.

Romero Sánchez, E., & Hernández Pedreño, M. (2019). Análisis de

las causas endógenas y exógenas del abandono escolar temprano: una

investigación cualitativa.

Salvà Mut, F.,Moso Díez, M., & Quintana Murci, E. (2024). El abandono de los estudios en la Formación Profesional en España: diagnóstico y propuestas de mejora. CaixaBank Dualiza.

Sánchez-Bolivar, L., Escalante-González, S. & Vázquez, L. M.

(2023). Competencias profesionales en el alumnado de formación

profesional de grado superior según género y religión.

Santibáñez Gruber, R., Fonseca Peso, J., & Pérez Hoyos, J. (2024)

En A. Moro, & M. Ruiz-Narezo, (Eds.). (2024).

Sarceda-Gorgoso, M. C., & Barreira-Cerqueiras, E. M. (2021). La

Formación Profesional Básica y su contribución al desarrollo de

competencias para el reenganche educativo y la inserción laboral:

percepción del alumnado.

Sarceda-Gorgoso, M. C., Santos-González, M. C. & Sanjuán Roca, M. M. (2017). La Formación Profesional Básica: ¿alternativa al fracaso escolar? Revista de Educación, 378, 78-102. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-378-362

Sen, A. (2000).

Sureda-García, I., Jiménez-López, R., Álvarez-García, O., &

Quintana-Murci, E. (2021) Emotional and behavioural engagement among spanish

students in Vocational Education and Training.

Tarabini A., Curran M., Montes, A., & Parcerisa, L. (2019) Can

educational engagement prevent Early School Leaving? Unpacking the

school’s effect on educational success.

Van Middelkoop, D., Ballafkih, H., & Meerman, M. (2017).

Understanding diversity: a Dutch case study on teachers 39; attitudes

towards their diverse student population.

Viniegra-Velázquez, L. (2021). Colonialismo y educación médica:

¿educare o educere?

Información de contacto / Contact info: Andoni Piñero Pradera. Universidad de Deusto. Facultad de Educación y Deporte. Avenida de las Universidades, 24, Deusto, 48007 Bilbao, Bizkaia, España.