The Second chance education model in Spain as an effective model

El modelo de segunda oportunidad educativa en España como un modelo eficaz

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-688

Luis Aymá González

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6557-9066

Roberto García Montero

Peñascal Kooperatiba

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0191-3277

Joaquín Vila Vilanova

Universitat de València

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-9521-0149

Elena Bayón Torres

Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad

Abstract

Early school leaving is a phenomenon that places adolescents and young people in a vulnerable position regarding to their future labour and social integration. Many of these young people already have personal, economic, social, or family constraints before leaving the school system, which increases their vulnerability. The aim of this article is to analyse and present second-chance schools (SCS) in Spain as an effective and successful alternative that allows young people aged 15 to 29 who have left school prematurely to return to the education system and move towards employment with more chances of success. The research focuses on the analysis of data that the Spanish Association of Second Chance Schools (SCS Association) collects through standardised tools regarding the training offered, the functioning of the school and the indicators of its activity in terms of the results obtained. As an innovative aspect, the Association has its own accreditation process structured around 29 items, in which independent audits are carried out to guarantee quality standards in educational processes and practices in terms of: the social and professional integration of students; the development of skills; collaboration with public administrations and companies; and networking. They offer training in different professional fields with a variety of types and durations, which allows them to adapt to the needs and characteristics of each young person. Their work, structured around key areas such as the individualisation of pathways and the development of transversal skills, which are fundamental not only for professional development but also for life, makes SCS as an educational and social benchmark, backed by a 63% success rate in return to education or finding a job six months after leaving school.

Keywords:

second chance schools, individualized education programs, disadvantaged youth, vocational education and training, early school leaving

Resumen

El abandono educativo es un fenómeno que sitúa a adolescentes y jóvenes en una posición de fragilidad ante su futura inserción laboral y social. Muchos de estos jóvenes ya cuentan con condicionantes personales, económicos, sociales o familiares previos a la salida del sistema escolar, lo que aumenta su vulnerabilidad. Este artículo tiene como objeto analizar y presentar a las escuelas de segunda oportunidad (E2O) en España como una alternativa eficaz y de éxito que permite que jóvenes de 15 a 29 años que han abandonado prematuramente los estudios, retornen al sistema educativo y transiten con mayores garantías hacia el empleo. La investigación se centra en el análisis de datos que la Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad (Asociación E2O) recoge a través de herramientas estandarizadas en torno a la oferta formativa, el funcionamiento de la escuela y los indicadores de su actividad en cuanto a los resultados obtenidos. Como aspecto innovador, la Asociación cuenta con un proceso de acreditación propio estructurado en 29 indicadores, en el que se realizan auditorías independientes que garantizan unos estándares de calidad en los procesos y práctica educativa en torno a: la integración social y profesional del alumnado, el desarrollo de competencias, la colaboración con administraciones públicas y empresas y el trabajo en red. Ofrecen formación en distintos ámbitos profesionales con diversidad en cuanto a su tipología y duración, lo que permite adaptarse a las necesidades y características de cada joven. Su trabajo vertebrado en ejes clave como la individualización de los itinerarios y el desarrollo de competencias transversales, fundamentales, no sólo para el desarrollo profesional sino también para la vida, posicionan a las E2O como un referente educativo y social, avaladas por una tasa de éxito del 63% -retorno educativo o inserción laboral a los seis meses de la salida de la escuela-.

Palabras clave:

Escuelas de segunda oportunidad, Programas de educación individualizados, Juventud vulnerable, Formación Profesional, Abandono educativo tempranoIntroduction. The second chance

For decades, the concept of employability has been under review in response to constant and rapid changes in the labour market (Gazier, 2001; Llinares et al., 2020; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). From the disability and ability to work dichotomy at the start of the 20th century (Mäkikangas, et al., 2013), by the 1960s and 70s employability was defined as the appropriate fit between professional competence and the demands of the labour market. In the 1980s, the concept of employability expanded to cover the ability to find a job, keep it, and acquire job-seeking competences (Gazier, 2001). Competences started to be understood as key for accessing work (Rothwell & Arnold, 2007 as cited in Mäkikangas et al., 2013). The rapid transformation of the workplace, increased volatility and segmentation, increase in temporary contracts, highly transitory cyclical unemployment, digitalisation, offshoring, etc. have a significant effect on young people, especially the most vulnerable ones (Ficapal-Cusí & Motellón, 2022; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2022). This new scenario requires people to have a different relationship with work and training, based on their capacity for adaptability, flexibility, and continuous retraining to face multiple incidences of joining and leaving the labour market throughout their lives, aspects that are embedded in the concept of employability. This shift entails expanding intervention for social and workplace inclusion into other areas such as personal development, better interpersonal relations, self-determination, self-knowledge, the capacity to choose for oneself, and comprehension of one’s own identity, questions that point beyond accessing a job as a guarantee of social and workplace inclusion (Serrano, Martín, 2017; Zugasti, 2016). The working model of second chance schools responds to the challenge of this new context by integrating three key elements into its model: transversal competences, personalised accompaniment, and the concept of positive leaving.

The problem of early school leaving and school failure cannot be addressed by a vision centred solely on formal education and the school as the educational institution of reference. Instead, it must include a broader outlook that encompasses the elements and phenomena that this educational and social exclusion generate (Tárraga-Mínguez et al., 2022).

Pedagogical and didactic movements centred on individual attention have resulted in a more human and personalised teaching model that focusses the process of education on a model that centres students, accommodating their capacities and interests as individuals to minimise harm to them from the homogenisation of education by educational institutions (Guerrero & Ruiz, 2020).

In order to respond to these harms and experiences of school failure

owing to the homogenisation of education, in 1995 the European

Commission set out the foundations of the response to this problem for

vulnerable young people through its white paper on education and

training,

The European Commission’s white paper on education (1995) identified five objectives in the field of education that states should implement policies to achieve. It is in the third objective, combating exclusion, offering a second chance through schools, that the pilot experience of second chance schools as a response to this need is born. The European Commission itself has identified the experiences of second chance schools as those that can offer the best educational provision to students who have been excluded from the formal education system so that they can continue with their training and work on developing their socio-emotional aspects (Corchuelo Fernández et al., 2016; European Commission, 2001).

Second chance schools centre on young people who have either had an unsuccessful experience of education or have not acquired the qualifications and basic skills needed to access the labour market or whose personal situation prevents them from accessing or continuing in the mainstream training system. For this reason, the second chance is understood as the bridge towards optimal social and workplace insertion. Redressing these difficulties frames the principal objectives to be developed by second chance schools (European Commission, 2001; García-Montero, 2018).

Two second chance schools from Spain participated in this European pilot scheme – one from the Basque Country and the other from Catalonia – but it was not until 2015 that a group of third-sector social-action bodies from different parts of Spain, with wide experience and long track records of working with young people in situations of exclusion from the formal education system, decided to start establishing the network of second chance schools – SCSs since their appearance in Spain – (García-Montero, 2018; Thureau, 2018).

Spain’s SCS network started by using its French counterpart as a

reference point in direct contact with the SCS of Marseilles. The first

six institutions that defined and structured the Spanish second chance

school model were Fundación Adsis, Fundación El Llindar, Fundación

Federico Ozanam, Peñascal Kooperatiba, Fundación Don Bosco, and

Fundación Tomillo. On 11 November 2015, these institutions signed the

manifesto

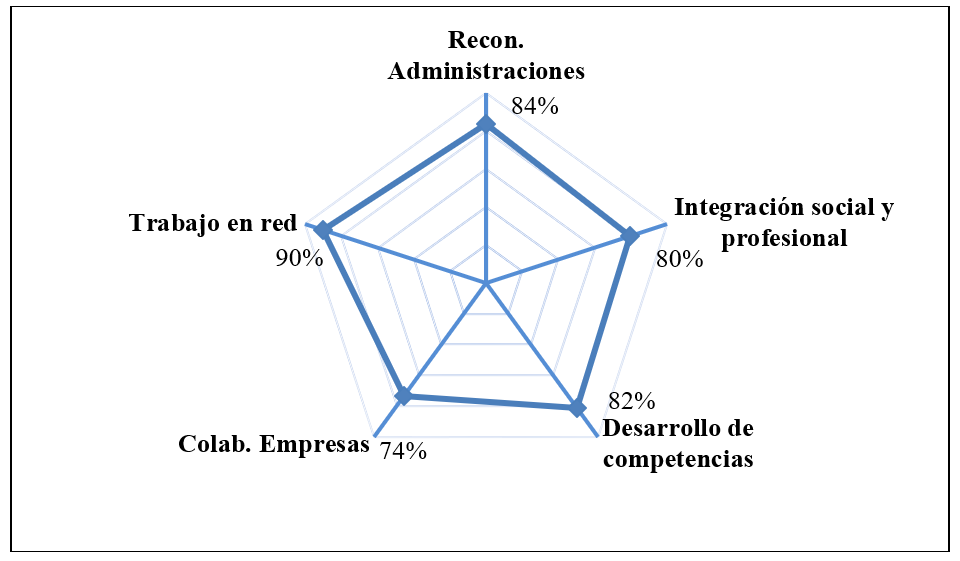

The SCS Association has implemented its own model set out in 29 indicators grouped into five dimensions: recognition of the SCS model by public administrations; professional and social integration of unemployed young people who are outside the education system or at risk of exclusion from it; social and professional competence development; collaboration with businesses; and networking. Accordingly, the Association defines the SCS model as an effective socio-educational intervention model of proven quality that has the primary objective of improving the situation of unemployed young people who have been excluded from the education system (García-Montero, 2018; Thureau, 2018).

The history of the SCS Association is still relatively short. However, numerous studies have focussed on defining the target population of SCS institutions, as well as their contribution to personal and social development, reincorporation into the education system, and subsequent workplace insertion (González-Faraco et al., 2019.; Fernández et al., 2014; Tárraga-Mínguez et al., 2022).

Description of the SCS Association

SCSs offer young people who have been excluded from the formal education and training system an alternative model based on innovative standards aimed at minimising early school leaving and school failure (European Union, 2017; Fernández et al., 2014; Tárraga-Mínguez et al., 2022). In Europe, the movement of this type of schools shares some common principles, but the intervention and action models are adapted to the context of each country where they are located. In the case of Spain, the birth of the SCS Association in 2016 set a benchmark in relation to the other European SCS associations by implementing a standardised accreditation process for SCSs (García-Montero, 2018).

SCSs in Spain cater for young people aged from 15 to 29 years with a record of negative experiences of the education system, low or no academic training, and who have experienced unemployed or have experience of work that requires few qualifications. Their aim is to facilitate access to the labour market, offering practical training, or return to the formal education system to continue with official training (Martínez-Morales et al., 2024).

Until the publication of

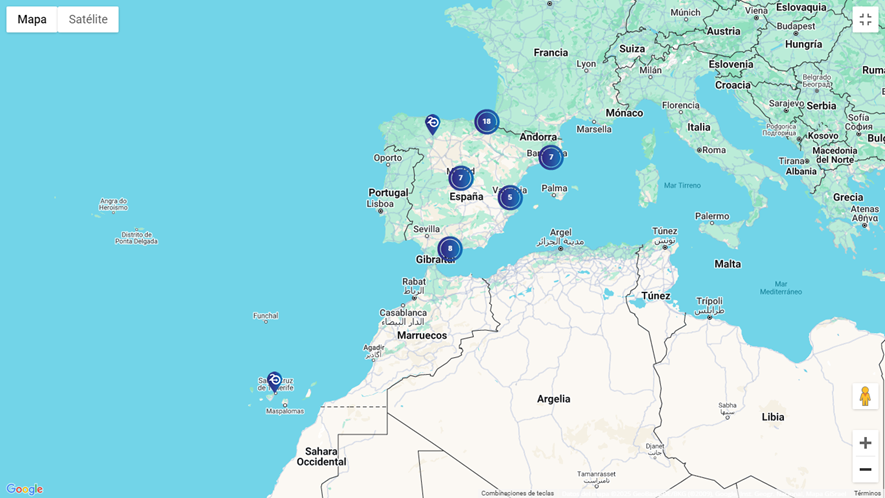

FIGURE I. Distribution of Formally Accredited SCSs in Spain as of 31 December 2024

Source: Second chance schools (SCS) accredited in Spain (accredited units) extracted from the website of second chance schools in Spain. https://www.e2oespana.org/unidades-acreditadas/#1664547208847-a6c1ef54-284b

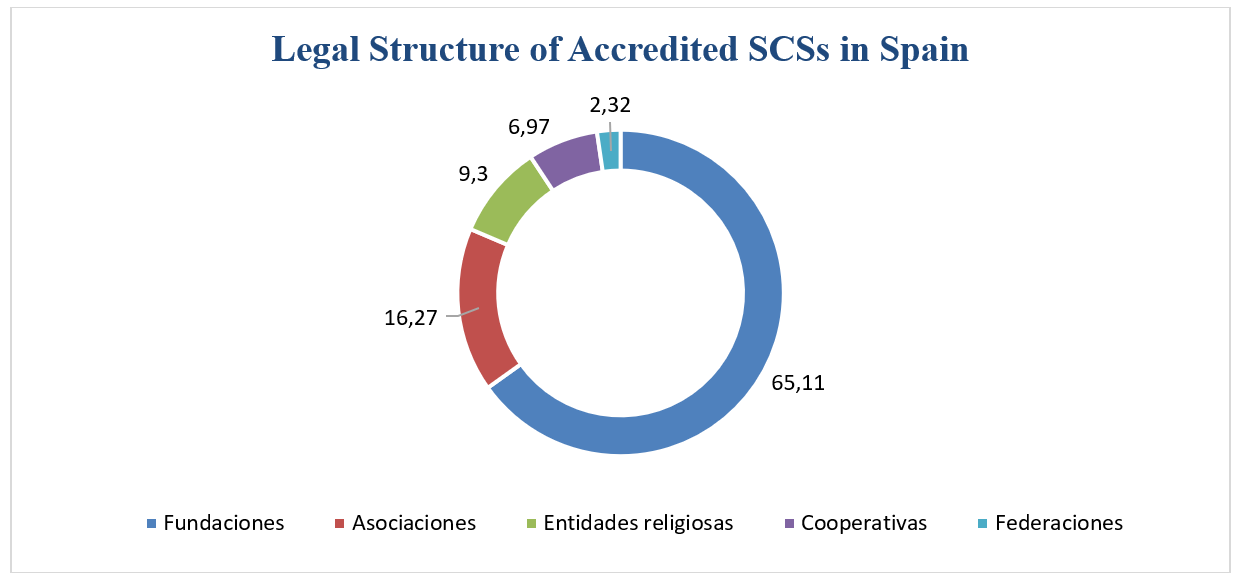

The variety of types of schools that make up the Association is also a distinguishing feature, as while it was established relatively recently (2016), a large majority of the member organisations have a record of decades working with the population of young people excluded from the education system using a pedagogical methodology in line with the SCS model (Marhuenda et al.; 2022; Marhuenda et al., 2024). Based on the data in Figure II, within this diversity we can find bodies with a wide range of legal structures, with these foundations being the most numerous type, followed by cooperative associations and federations.

FIGURE II. Legal Structure of Accredited SCSs in Spain

Source: Marhuenda Fluixá, F; Chisvert Tarazona, M.J (Eds). OTR2020-21121INVES contract, signed between the Universitat de València and the Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad. Retrieved January 22, 2025, from www.madreams.es

Most of the organisations that are members of the Association are bodies with strong local roots in the area where they are based, normally linked to neighbourhood or community action movements in the districts where they are located. These local roots give them a high level of recognition by other social organisations, by the administration, and by users, which to a great extent makes them benchmarks at a local and autonomous-community level (García-Montero, 2018; Marhuenda et al., 2024; Martínez-Morales et al., 2024).

A third of the total of SCSs derive from social work by religious bodies, which, through their social initiatives, promoted direct intervention with residents of the most vulnerable neighbourhoods. These bodies that support them, mainly do their educational work in the field of formal education by implementing an educational offer in compulsory secondary education or in formal professional training. At the same time, there is a smaller group among the total number of schools that has an organic basis close to the social economy (Marhuenda et al., 2024).

The process of accreditation of an SCS

The SCS Association has a defined process for accreditation as an SCS (Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad, 2017, 2022). The structure of this uses the Association’s charter of principles as a benchmark (Asociación E2O, 2015), which is based on the conclusions of the original model developed by the European Commission in its pilot project for this type of school (European Commission, 2001). The Spanish model has 5 basic principles:

- Recognition by the administrations.

- Lasting social and professional integration of the group.

- Personal, social and professional competence development.

- Collaboration with businesses.

- Networked activity.

This points towards a principal goal to “facilitate analysis of the processes carried out in the school and to help with the qualitative improvement of these processes, steering decision making to lead to excellence” and a secondary goal, the logical outcome of the process: “To value the functioning of the school in reference to the SCS model in Spain facilitating the decision to accredit it as a Second Chance School, by the Association” (Asociación E2O, 2017, 2022, p. 7, authors’ own translations).

The application of the process is structured around 29 indicators, grouped into the model’s different principles. These indicators have been defined by people from the association itself, experts in the field of early education leaving, training, and the field of employment, and they have been validated by academic experts from the university sector and professionals in evaluating education.

Analysis of this model shows that it supports schools that:

-

have the backing and recognition of the public administrations responsible for the education, training, and labour integration of young people with difficulties;

-

operate with approaches aimed at young people achieving stable, long term social and professional integration in the social setting where they live;

-

have a holistic educational offer that includes the development of personal, social and professional competences, not just academic ones, and to do so use methodologies and teaching practices that are innovative, inclusive, and facilitate an individualised response to each person’s needs;

-

involve in their activity the businesses that form part of the productive framework of the ecosystem of which they form a part;

-

and are characterised by maintaining cooperation and an approach of networked activity with stakeholders from their own setting and from others (health–healthcare, social, residential, protecting children and young people, etc.) which are necessary for consistency with the holistic approach to the development of a person.

The process is based on collegiate self-evaluation by the professionals responsible for management and organisation in each school as well as independent audits that confirm the existence of evidence that supports the schools’ self-evaluation. In the case of any discrepancy, it is adapted, on the basis of the descriptors and criteria of the process itself. As a result, an overview of the educational practice of the school is obtained, according to the model of standards of excellence defined by the Spanish association.

The accreditation process as a whole features a diverse and periodically renewed committee of experts to ensure that the actions (self-evaluations, audits, follow-up, collection of valuations and submissions, analysis and conclusions, etc.) done in it have a guarantee of quality and good functioning. In addition to this, with all of the information obtained, and in contrast with the Association’s governing bodies, proposals are made for improving the process itself.

Consequently, the configuration of the second chance model in Spain is dynamic and constantly developing, and it can adapt to the social reality in which SCSs carry out their activity.

Types of students attending SCSs in Spain

As Palomares et al. (2024) observe, early school leaving is a standardised indicator that can be compared across Europe that refers to young people who do not achieve a minimum level of secondary education qualifications.

The profile of young people that make up the students in second chance schools is very diverse and varied. Its is strongly marked by the institutional design of the SCS programme, fundamentally for young people with negative educational trajectories who come from disadvantaged social settings and are in a situation of risk and/or social exclusion (Martínez-Morales et al., 2024; Palomares et al., 2024; Tárraga-Mínguez et al., 2022).

The SCS Association itself defines the descriptor variables to be considered in the profile of the people who form part of the schools (Asociación E2O, 2017, 2022, pp. 2). These relate to their age, academic qualifications, academic situation and employability, and social integration profile (Table I).

TABLE I. Identifying Characteristics of the SCS Collective at the Time They Join the School

| Age | Qualifications | Academic situation | Employability and social integration profile |

| Being aged between 15 and 29 years, according to a criterion of academic age and reaching that age during the year that the academic year begins. | Not having a post-compulsory secondary or higher qualification | Fulfilling one of the following conditions:

|

Fulfilling one of the following conditions:

|

Source: Produced by the authors based on the accreditation process of the SCS Association (2017, 2022, p. 2).

The various studies of SCSs that have been done (Marhuenda et al., 2024; Merino-Pareja & García-Gracia, 2022; Palomares, Palomares et al., 2024) have found that students from SCSs in Spain are fully diverse and heterogeneous. One key aspect of their students in Spain is that the majority are male, with ¾ of the total being male compared with ¼ female. In this case, the phenomenon of masculinisation of school leaving is maintained, as García (2011) notes. Furthermore, there is evidence of the situation of exponentially increased vulnerability of female students in a school-leaving situation that makes them even less visible (Merino Pareja & García-Gracia, 2022).

The bulk of the SCS population are in the 15 to 20 years age bracket, with this population group representing more than 50% of all of the young people from SCSs, although it is true that the population as a whole is aged between 15 and 29 years and they participate in the different programmes indistinctly without being distributed by age ranges.

The family situation of most of the young people is suboptimal and precarious considering economic capital as well as cultural capital. More than half of the families have major financial challenges to reach the end of the month, although a small percentage reports not having this issue. With regards to cultural capital, the parents’ level of studies is low or none. A small percentage stand out for having parents with university level studies, in line with what has been observed by García Gràcia and Valls (2018) who indicated that the disconnection from higher education is not exclusively an indicator of families from a low social background (Palomares et al., 2024).

The background or country of origin is also a characteristic of the group of SCS students. Migrants make up 1/3 of the total people at these schools. This aspect reflects the vulnerability of young migrants, who have a higher likelihood of leaving education and face greater challenges in achieving a degree of continuity in their path through Basic Professional Training (García Gràcia & Valls, 2018).

The characteristics described indicate that within the population group aged from 15 to 29 of SCS students, numerous diverse and heterogeneous factors define people as individuals, confirming the great diversity of the group of young people who participate in SCSs in Spain.

Description of the data collection process. Procedure and instruments

The data collection process is arranged in three fields: the training offer; the functioning of the school; and the indicators for its activity with regards to the results obtained. To do this, a series of standardised files sent by each school to the association and a digital app with access by username and password are used.

Training offer

Instruments

Each school completes a data collection table and submits it to the Association before being accredited for the first time and then submits it periodically (annually). The table displays identifying details, in some cases from a closed list of answers, about the accredited school and about the following variables:

- Name of the training offered

- Total number of students

- Ratio of students per group

- Professional family

- Value and effects of qualification and certification

- Benchmark professional qualification level (where applicable)

- Business experience

- Funding source

- Notes

Process

The data collection is done for each previous academic year. This timetable coincides with the submission of data by each school in relation to the activity and results indicators.

The data about the training offer of accredited SCSs in Spain collected in this article refer to the 2022–23 academic year. The most up to date ones at the time of writing are included.

Functioning of the school

Instruments

The collection of data about the functioning of the school uses tools constructed specifically for the process of accreditation as an SCS (Asociación E2O, 2025). The main one is the SCS accreditation scale (Annexe I), which is a Likert-type scale with 29 indicators, grouped according to the 5 principles of the SCS Association. Each indicator has 5 levels of excellence (Excellent, Good, Satisfactory, Unsatisfactory, and Not fulfilled). Each one has a descriptor or rubric. Taking these into account, the school must evaluate itself, identifying the features of its practice and evidence to support them (Asociación E2O, 2017, 2022, pp. 20-31). As auxiliary elements to help carry out this process, with the due rigour there is a frequently asked questions document, including doubts about each indicator and the key criteria and elements to use to define the level of excellence, and also digital tables that set out the responses to the scale, the evidence associated with each response, and the school’s identifying details.

Process

Depending on when a school decides to enter itself for the accreditation process, it sends the association the self-evaluation based on the scale and requests a visit by the professionals from the independent agency who perform the in-person audit to validate the supporting evidence for the self-evaluation. After this audit, a report is issued on its result with the level of excellence achieved by each school on each of the indicators with comments on its functioning. A school’s positive accreditation is valid for 4 years, and has to be renewed through another audit. In each period between audits (2 years from the audit), a follow-up of the situation of the accredited SCS is performed by experts from the association.

The data regarding the functioning of accredited SCSs in Spain collected in this article refer to each school’s most recent audit, dated 31 January 2025, and were provided by the SCS Association.

Indicators of activity and results obtained

Instruments

A table is used to collate data on activity indicators that each school completes periodically and submits to the Association (annually by periods of September–August academic year). The table includes indicators regarding:

- Student numbers;

- Their profile in accordance with the following variables:

-

Gender

-

Age

-

Nationality

-

Age

-

Academic level when joining

-

Qualification level when joining

- Results according to the following variables:

-

Number of young people who leave the SCS

-

Academic level when leaving

-

Qualification level when leaving

-

Stability and Duration of the SCS pathway

-

Situation 6 months after leaving according to the positive result index (success rate)

- Data on the figures of the SCS (hours of training, number of professionals and budget)

Process

As positive leaving (success rate) is collected in the activity indicators and this is measured 6 months after leaving the E2O, the data collection, which is done annually and by academic year, is requested from each accredited school in the period between February and April.

“The success rate measures the situation of the young people who have left the E2O (a part of the students). The rate shows the people who have joined the labour market or formal or non-formal training in another centre six months after leaving.” (Asociación E2O, 2025).

Educational offer and characteristics of SCSs in Spain

Training offer

At the end of the 2022–23 academic year, 46 schools in Spain were accredited as SCSs. Of these, according to the type of offer (Table II):

- Twenty-six (57%) offer training integrated into the formal

education system, although 11 of these do so solely through

autonomous-region measures of attention to diversity that enable the

externalised schooling of 15-year-old students in schools other than

compulsory secondary education

schools

3 . - Fourteen (30%) offer qualifications from the professional training system (Grade D in the terminology of Spain’s new professional training system).

- Eighteen (39%) offer non-formal training programmes promoted and formal by the competent educational administration in that autonomous community.

- Thirty-two (70%) provide a very broad and diverse offer of non-formal training programmes, with a wide range of values and effects as a result of successfully completing them: certifications of qualifications of a variety of levels and degrees from the employment system, certifications that are only of value and effective within the autonomous community, unofficial certifications.

TABLE II. Descriptive analysis of the distribution of schools accredited as SCSs in Spain by type of offer.

| Type of training | Type of system | Number of SCSs offering it (percentage of the total population) |

| Attention to diversity measures in SCSs that integrate students aged 15 | Formal training | 16 (35%) |

| Basic PT | Formal training | 14 (30%) |

| Intermediate Training Cycles | Formal training | 5 (11%) |

| Advanced Training Cycles | Formal training | 1 (2%) |

| Non-formal training programmes promoted by autonomous community-level educational administrations | Non-formal training | 18 (39%) |

| Other programmes | Non-formal training | 32 (70%) |

Source: Produced by the authors based on data from the SCS Association.

As for their duration (hours of training of the programme or level of

teaching) per student, the analysis of the variety of the offer is very

broad. A total of 125 different values were collected, ranging from 3 to

1,330 hours per academic year (annual)

period

With regards to funding, the wide range of programmes and qualifications is also reflected in this area. The bulk of the funding (Table III) comes from the public administrations of the autonomous communities, most notably the ministries of education and employment (generally in separate departments in almost all of the autonomous community governments). However, a not inconsiderable number draw their funding from private sources (generally foundations and businesses), the funds of the bodies that own the school, or other sources (European Social Fund, multiple public administrations, or others).

TABLE III. Descriptive Analysis of the Distribution of Schools Accredited as SCSs in Spain by Funding Source

| Funding source | Number of programmes or qualification lines |

| Autonomous Community Government (Education) | 150 |

| Autonomous Community Government (Employment) | 53 |

| Autonomous Community Government (Education & Employment) | 12 |

| Private funding | 65 |

| Mixed (public and private funding) | 55 |

| European Social Fund (ESF) | 11 |

| Own funds | 27 |

| Multiple Administrations | 8 |

| Others | 83 |

| TOTAL | 464 |

Source: Produced by the authors based on data from the SCS Association

Functioning of the school

With regards to the functioning of the schools, data are presented relating to the level of excellence of each unit with regards to the SCS model according to the result of the most recent audit (Table IV). These show the percentage of distribution of the total population of accredited SCSs in each indicator on the scale for SCS accreditation. The accreditation model has 18 indicators considered essential (shown in block) and 11 complementary ones.

TABLE IV. Descriptive analysis of the distribution of schools accredited as SCSs in Spain by level of excellence.

| INDICATOR | LEVEL OF EXCELLENCE | ||||

| Excellent | Good | Satisfactory | Unsatisfactory | Not fulfilled | |

| Collaboration with public administrations | 46% | 26% | 28% | 0% | 0% |

| Stability of financial and structural resources of the SCS | 38% | 24% | 38% | 0% | 0% |

| Stability of human resources of the SCS | 90% | 8% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Involvement in standardised SCS model | 30% | 58% | 12% | 0% | 0% |

| Voluntary involvement of young people in the SCS | 48% | 46% | 6% | 0% | 0% |

| Duration of training pathway | 74% | 24% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Individualisation and flexibility of learning environment | 66% | 32% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Offer of alternative pedagogical model | 56% | 36% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Return to formal system and access to work | 62% | 16% | 16% | 6% | 0% |

| Offer of PT with benchmarks recognised in national training & qualifications system | 22% | 50% | 28% | 0% | 0% |

| Guidance and monitoring of the young person | 26% | 26% | 48% | 0% | 0% |

| Equality of opportunities | 94% | 4% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Holistic attention | 23% | 41% | 36% | 0% | 0% |

| Protection of minors and vulnerable people | 58% | 38% | 4% | 0% | 0% |

| Work on socio-personal and technical-professional competences | 64% | 26% | 10% | 0% | 0% |

| Adaptation and individualisation of programme | 76% | 22% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Work on key competences | 30% | 38% | 32% | 0% | 0% |

| Influence of labour market on the training design | 26% | 30% | 44% | 0% | 0% |

| Work with Life Projects | 64% | 32% | 4% | 0% | 0% |

| Promotion of values in young people at the SCS | 50% | 32% | 18% | 0% | 0% |

| Business involvement in training | 38% | 32% | 22% | 8% | 0% |

| Alignment of interests between young people and world of work | 20% | 30% | 48% | 2% | 0% |

| Awareness raising in businesses and CSR | 46% | 30% | 20% | 4% | 0% |

| Involvement of business in design of training | 22% | 26% | 52% | 0% | 0% |

| Business placements for young people in the SCS | 70% | 14% | 16% | 0% | 0% |

| Coordination of SCS with complementary stakeholders | 86% | 8% | 6% | 0% | 0% |

| Systematising of networked activity | 78% | 14% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Involvement in SCS Association | 76% | 8% | 6% | 0% | 10% |

| Intervention with people aged under 15 | 46% | 26% | 28% | 0% | 0% |

Source: Produced by the authors based on data from the SCS Association.

These data show that the proportion of schools achieving ratings of Good or Excellent in 14 of the indicators is ≥ 85% (levels of excellence in block), which makes these the main strengths of the functioning of this type of school.

When viewing the level of excellence of the operation of the whole population of accredited SCSs in Spain (Figure III), it is apparent that they achieve a minimum value of excellence of 74% of the total (Business Collaboration axis) and a maximum value of 90% (Networked Activity axis). The degree of excellence stands out with a high value in all of the axes of analysis.

FIGURE III. Level of Excellence by Principles Axes

Source: Produced by the authors based on data from the SCS Association.

Activity indicators and results obtained. Positive result (success rate)

According to the activity indicators (Asociación E2O, 2025), in the 2022–23 academic year, 8,493 young people received training in 46 SCSs in 10 Autonomous Communities with the support of 957 professionals. Most of them were male (71%) and were aged between 15 and 25 years (94%), as Figure IV shows.

FIGURE IV. Population Distribution of Students by Gender and Age Success rate.

Source: Asociación E2O, 2025. https://www.e2oespana.org/datos-clave/

The success rate is defined in the SCS Spain model as people who have joined the labour market or are in formal or non-formal training in another centre. This rate is measured six months after leaving the training centres. A longitudinal analysis of the success rate indicates that this has always been above 60%. Bearing in mind that the population served comprises young people who are excluded from the mainstream education system, cannot access it, or have major difficulties in so doing and are at a serious risk of professional and social exclusion, these are very important figures, representing more than 5,000 people each year who escape successfully from a situation of serious risk of social professional and academic exclusion.

Limitations and new lines for future research

This study considers SCSs that are accredited and are involved with the Association. In Spain there are other educational mechanisms that implement actions within the particular sphere of the second chance but are not connected to the Association, and so while this study does cover a highly significant amount of this reality, it does not reach the whole of the currently existing population of providers of these characteristics.

The following are desirable new lines of future research related to the aim of this study:

- Analysing the value and effects of the training offer of SCSs by autonomous communities.

- Study of the context of second chance schools, in relation to their stability and integration in the education system.

- Good practices in SCSs in creating flexible and individualised learning pathways, as well as in the processes of accompaniment and guidance of collectives facing difficulties.

Conclusions

The roll-out and social recognition of each school in the territory is one of the keys for the success of the SCS model as it enables a flexible response that is adapted to the setting where it carries out its transformational activity. This aspect makes them social benchmarks and organisations that give coherence to the areas where they are located.

The networked activity of SCSs, understood as a collaborative space for generating shared knowledge, involves a process of constant critical reflection, self-evaluation, and updating that, in the case of the SCS Association, has been able to develop standardised models that guarantee the quality of the actions, such as the independent audit model.

SCSs are part of and to some certain extent also influence active employment policies, thus seeking to meet the needs of young people whom public intervention has been unable to reach effectively. For this reason, SCSs create individualised socio-training pathways, preferably aimed at each one of the young people that they serve (Marhuenda et al., 2024). These training pathways take into account the circumstances with which each young person first enters an SCS, at a social, emotional, contextual, competency etc. level, defining and shaping the start or joining of different training processes that can be facilitated from it. This flexibility in the creation of training pathways is, in part, facilitated by the acquisition of basic, transversal and technical-professional competences, as key elements in their intervention in all of the programmes of the SCSs. Competence-based work in young people’s personalised pathways allows greater individualisation of the intervention in line with working standards and the setting of indicators of acquisition of these competences that facilitate personal reconstruction, re-engagement with training in the education system, and social-labour insertion (Tárraga-Mínguez et al., 2022).

Thanks to their flexibility, these schools have the capacity and options to integrate training of very varied types and durations into the design of these pathways very naturally (professional training, occupational training, formal training, businesses courses and placements, certificates of professionalism, etc.). This enables them to overcome the compartmentalisation that often exists between the different training offers and the responsible authorities. These types of training, linked by the idea of the pathway, are integrated and made meaningful.

The diversity of training activities is a factor that facilitates young people’s integration and success in the education–training system. Each person’s initial circumstances (competences, personal, social, or family) shapes the commitment, motivation, and availability with which he or she attends an SCS. This diversity allows all young people to choose from different training possibilities, which they can also combine, to reach the same goal. Some young people cannot initially commit to long-term training (one or two years) for a variety of reasons, such as previous experience of failure, because they are still defining their professional goals, or because their personal or family economic circumstances, for example, do not permit it. Nonetheless, many SCSs provide other training possibilities under standards of quality that favour the development of pathways with commitments that are adapted to their needs and that enable them to take decisions on their professional careers.

The working model of SCS schools addresses the challenge of including young people who face greater difficulties. It does this by including three key elements: transversal competences, personalised accompaniment, and the concept of positive leaving. Transversal competences are life competences relating to attitudes and behaviours that favour the appropriate development of performance in social and workplace settings (self-knowledge and self-confidence, team work, interpersonal relations, responsibility, managing emotions and conflicts, and tolerance) (Villardón-Gallego et al. 2020). Personalised accompaniment, which considers personal, social and cultural characteristics (López-Bermúdez et al., 2024), is centred on models of socio-labour guidance adapted to the needs of each young person that go beyond a basic strategy intended for technical-professional preparation in order to access employment. The success rate is based on the concept of positive leaving, which involves acquiring the transversal competences that enable young people to be masters of themselves, undertake actions purposefully, choose what type of actions to undertake to influence and change their own situation, and recognise their own strengths and interests, that is to say, building agency, which is understood as key to handling the uncertainty of working life (Salinas, 2022). Accordingly, the SCS Association’s working model coherently connects young people’s development of transversal competences with their capacity to take decisions and their ability act to drive change in their lives as a guarantee of positive leavings, something that involves reconsidering the concept of employability with a broad perspective.

Annex I

Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad (31 de enero

de 2025). Escala para la acreditación E2O.

Notes

Referencias bibliográficas

Asociación Española de Escuelas Segunda Oportunidad (2015

Asociación Española de Escuelas Segunda Oportunidad (2017, 2022).

Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad (31 de enero

de 2025). Proceso de acreditación Escuela de segunda oportunidad (E2O).

Corchuelo Fernández, C., Cejudo Cortés, C. M. A., González Faraco, J.

C., & Morón Marchena, J. A. (2016). Al borde del precipicio: las

Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad, promotoras de inserción social y

educativa. IJERI:

European Commission (2001).

Fernández, C. C., Cortés, C. M. A. C., Faraco, J. C. G., &

Marchena, J. A. M. (2014).

Ficapal-Cusí, P., Motellón, E. (2022) Futuro del empleo: nuevos

desafíos para aspiraciones pendientes. Oikonomics.

García, J. S. M. (2011). Género y origen social: diferencias grandes

en fracaso escolar administrativo y bajas en rendimiento educativo.

Garcia Gràcia, M., & Valls Casas, O. (2018). Trayectorias de

permanencia y abandono educativo temprano: Análisis de secuencias y

efectos de la crisis económica.

García-Montero, R. (2018). Las Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad (E2O)

en España.

Gazier, B. (2001). Employability: The complexity of a policy notion.

en Weinert, P., Baukens, M., Bollerot, P., Pineschi-Gapánne, M. y

Walwei, U. (Eds.)

González-Faraco, J. C., Luzón-Trujillo, A., &

Corchuelo-Fernández, C. (2019). Initial vocational education and

training in a second chance school in Andalusia (Spain): A case study.

Guerrero, J. P., Ruiz, J. A. A. (2020). La educación personalizada

según García Hoz.

López-Bermúdez, A., Caro Blanco, F., & Mestre Miquel, J.M.

(2024). Impacto de los programas de inserción sociolaboral en la calidad

de vida de las personas usuarias: estudio transversal del caso de la

Fundación Deixalles.

Llinares Insa, L., Córdoba Iñesta, A.I., & González Navarro, P.

(2020). La empleabilidad a debate: ¿qué sabemos sobre la empleabilidad

como estrategia de cambio social?, CIRIEC-España,

Mäkikangas, A., De Cuyper, N., Mauno, S. & Kinnunen, U. (2013) A

longitudinal person-centred view on perceived employability: The role of

job insecurity.

Marhuenda Fluixá, F; Chisvert Tarazona, M.J (Coord.); García Gracia, M; Merino Pareja, R; García Rubio, J; Martínez Morales, I; Palomares Montero, D. & Ros Garriga, A. (2022). Contrato OTR2020-21121INVES, suscrito entre la Universitat de València y la Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad.

Marhuenda Fluixá, F., Palomares Montero, D., Ros Garrido, A., Merino

Pareja, R., García Rubio, J., García Gracia, M., Chisvert Tarazona, M.

J., & Córdoba Iñesta, A. I. (2024).

Martínez-Morales, I., Marhuenda-Fluixà, F., Chisvert-Tarazona, M. J.,

& Tárraga-Mínguez, R. (2024). Análisis organizacional de las

Escuelas de Segunda Oportunidad Acreditadas en España.

Merino-Pareja, R., & García-Gràcia, M. (2022). Vías e itinerarios

de formación profesional: la persistencia de la asociación entre bajo

rendimiento y opción profesional.

McQuaid y Lindsay, R.W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of

employability,

Palomares Montero, D., Marhuenda Fluixá, F., Ros Garrido, A., Merino

Pareja, R., García Rubio, J., García Gracia, M., & Córdoba Iñesta,

A. (2024).

Romero-Rodríguez, S.; Moreno-Morilla, C. y Mateos Blanco, T. (Eds.)

(2022).

Salinas, J. (2022). Agencia del estudiante, competencia emprendedora

y flexibilización de las experiencias de aprendizaje.

Serrano, A. & Martín, P. (2017) From ‘Employability’ to

‘Entrepreneurial-ity’ in Spain: youth in the spotlight in times of

crisis.

Tárraga-Mínguez, R., García-Rubio, J., Chisvert-Tarazona, M. J.,

& Ros-Garrido, A. (2022). Escuelas de segunda oportunidad: una

propuesta curricular dirigida al retorno educativo y la inserción

profesional.

Thureau, G. (2018). La Asociación Española de Escuelas de Segunda

Oportunidad. La segunda oportunidad del sistema educativo.

European Union. (2017).

Villardón-Gallego L, Flores-Moncada L, Yáñez-Marquina L, &

García-Montero R. (2020). Best Practices in the Development of

Transversal Competences among Youths in Vulnerable Situations.

Zugasti,N. (2016). Transiciones laborales en Navarra. Una valoración

de la capacidad de integración del empleo.

Información de contacto / Contact info: Luis Aymá González. Facultad de educación, Centro Formación de Profesorado, Universdidad Complutense de Madrid. E-mail: luis.ayma@pdi.ucm.es