Value-added in Education: Mapping the contributions from Portugal and Spain

Valor Añadido en Educación: mapeo de las contribuciones de Portugal y España a la Investigación sobre la Eficacia Educativa (2000-2024)

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-700

Maria Eugénia Ferrão

Universidade da Beira Interior

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1317-0629

Abstract

This study examines Portugal and Spain´s contributions to Educational Effectiveness Research (EER) and value-added (VA) measures from 2000 to 2024 by analyzing 37 research papers published in Spanish (51%), English (38%), or Portuguese (11%). The analysis addresses three key questions: the knowledge production landscape, influential authors and articles, and the field´s evolving thematic structure. The scoping review method is used with bibliometric analysis, content analysis, and co-occurrence analysis through author keywords.The review covers 73 authors, with 32% of articles featuring international collaborations. Results show that 52% of studies use longitudinal data, and 19% rely on international large scale assessments. The majority of the articles (65%) consider school performance in mathematics, while 40% also address reading performance. Regarding the purpose, VA models are mainly used for educational improvement and evaluation, with no studies on school choice or high-stakes accountability. The study emphasizes the need for greater visibility and integration of EER in these regions and offers recommendations for future research, contributing to evidence-based educational policy and practice in Southern Europe.

Keywords:

evaluation, mapping science, school effectiveness, school improvement, value added model

Resumen

Este estudio examina las contribuciones de Portugal y España a la Investigación sobre la Eficacia Educativa (IEE) y a las medidas de valor añadido (VA) desde 2000 hasta 2024, mediante el análisis de 37 artículos de investigación publicados en español (51%), inglés (38%) o portugués (11%). El análisis aborda tres preguntas clave: el panorama de la producción de conocimiento, los autores y artículos influyentes, y la estructura temática en evolución del campo. Se utiliza el método de scoping review con el uso de análisis bibliométrico, análisis de contenido y de co-ocurrencia a través de palabras clave del autor. La revisión abarca a 73 autores, y el 32 % de los artículos presentan colaboraciones internacionales. Los resultados muestran que el 52 % de los estudios utiliza datos longitudinales y el 19 % se basa en evaluaciones internacionales. La mayoría de los artículos considera los resultados escolares en matemáticas, mientras que un 40% también trata los resultados en lectura. En cuanto al propósito, los modelos VA se emplean principalmente para la mejora y evaluación educativa, sin estudios sobre elección de escuelas o rendición de cuentas de alto impacto. El estudio enfatiza la necesidad de una mayor visibilidad e integración de la IEE en estas regiones y ofrece recomendaciones para investigaciones futuras, contribuyendo a políticas y prácticas educativas basadas en evidencia en el sur de Europa.

Palabras clave:

eficacia escolar, evaluación, mapeo científico, mejora educativa, modelo de valor añadidoIntroduction

For over 50 years, educational research has consistently demonstrated that teachers and schools have a profound and lasting impact on children´s development. This is especially evident from educational effectiveness research (EER), which focuses on the effectiveness of both teachers and schools in shaping educational outcomes (AERA-American Educational Research Association, 2015; Longford, 2012; Morganstein & Wasserstein, 2014; Reynolds et al., 2014). The concept of value-added (VA) in education and the use of value-added measures as a foundation for educational effectiveness research are essential (Sammons et al., 2016). The concept of VA in education emerged in the literature motivated by the field of educational evaluation. It first appeared in a study on the economics of education (Hanushek, 1971) that focused on evaluating teachers´ effectiveness, specifically the relationship between teachers´ characteristics and students´ learning gains. It was later discussed in an educational statistics article (Bryk & Weisberg, 1976), where the concept, its theory, and modeling were presented as the most appropriate methodological approach for evaluating the impact of interventions and programs aimed at improving student learning outcomes.

Hanushek (1971) formulates and explores three research questions that continue to be relevant and timely for educational policy worldwide: “(1) Do teachers make a difference? (2) Do schools operate efficiently? (3) What are the relevant characteristics of teachers and classrooms?” (Hanushek, 1971, p. 280). Acknowledging that the main interest of the conceptual and statistical model for the purpose of public policy focuses on the influence of school characteristics on students´ outcomes, the author explains the paper motivation as follows:

Past studies have given ambiguous answers to these questions, largely due to inadequate data. Specifically, no data set, which supplies accurate historical information on educational inputs at an individual level, has been available. (Hanushek, 1971, p. 280)

Those three relevant research questions had ambiguous findings until 1976 due to the use of inadequate data. In other words, until that time, no dataset had simultaneously satisfied two essential conditions: (1) use of accurate historical data on educational inputs; (2) consider student as the statistical unit of observation/analysis.

Bryk and Weisberg (1976), in turn, present the rationale for the “Theory of the value-added strategy”,

Rather than assuming a static input-output model, we prefer to think of an educational program as a dynamic intervention in an ongoing development process. […] The effect of any innovative program is to change the growth rate for the group of individuals exposed to it. The aim of the evaluation then is to compare the actual growth observed under an intervention with that which would have occurred in its absence. (Bryk & Weisberg, 1976, p. 130)

EER and VA research have primarily engaged the scientific community in the United States of America (USA) and in the United Kingdom (UK). Since the 1990s, there has been remarkable progress in addressing and resolving issues in statistical methodology, allowing for a more rigorous analysis and precise interpretation of both individual student performance and school academic achievement (Saunders, 1999). The adoption of a statistical model that incorporates the multilevel structure of the educational population (Plewis, 1997) became a methodological requirement in EER (Creemers, 2006; Goldstein, 1997). It addresses data characteristics—longitudinal design and multilevel structure—while theoretically justifying their necessity for understanding educational effectiveness and its multi-level impact on student development.

Six key methodological requirements frequently referred to EER (Goldstein, 1997; Mortimore, 1991; Strand, 2011, 2016) are outlined: (1) Assessment of prior knowledge and its inclusion as independent variable: This is typically achieved through the administration of standardized tests to evaluate students´ baseline knowledge in order to be part of the determinist component of the model; (2) Longitudinal data analysis: Studies must account for the longitudinal nature of learning by utilizing data that includes repeated observations of both the outcome variables (often standardized test scores) and relevant covariates for each student over time; (3) Multilevel population structure: It is essential to recognize and incorporate the hierarchical structure of the data, such as students nested within classrooms or schools, to ensure accurate analysis; (4) Consideration of external factors: Studies must account for out-of-school factors that could influence student learning, such as socioeconomic status or cultural background, which are key determinants of educational outcomes. In addition, studies focusing on the stability of value-added scores or changes in school performance over time must meet the following extra criteria. (5) Longitudinal data with multiple cohorts: A minimum of three cohorts is required to track performance changes and ensure robust longitudinal analysis; (6) Change-oriented analysis: To estimate long-term school performance, a focus on change-oriented analysis is essential (Gray et al., 1995), including methods that capture shifts in school effectiveness over time (Kyriakides & Creemers, 2008).

In addition, over the last 50 years the literature on VA includes the debate on its definition (Arias & Soto, 2009; Braun, 2005; Saunders, 1999), on the theoretical, conceptual and statistical modelling (Ballou et al., 2004; Ferrão & Goldstein, 2009; Goldstein, 1997; Ray et al., 2009), methodological requirements and data quality (AERA, 2015; Morganstein & Wasserstein, 2014), or the purpose and use of value-added measures (Darling-Hammond, 2015; OECD, 2008). The sharp development of EER is evident in hundreds of papers or handouts published (Reynolds et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2016). In mainland Europe studies are referred to in Belarus, Cyprus, Hungary, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Belgium, and Germany (Creemers, 2007; Thomas et al., 2016). Other European countries such as Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain are mentioned by Creemers, Stoll, Reezigt, and ESI Team (2007; p.826-858) regarding the Effective School Improvement (ESI) project, which run from 1998–2001. Murillo (2003) notes that research in Ibero-American countries has expanded over time, largely due to strong institutional support. Additionally, it is observed that a significant number of studies have been conducted in Spain. Regarding Portugal, the author refers to the participation in the ESI project. Little is known about the EER conducted in Spain and Portugal.

Recent literature reviews (Everson, 2017; Levy et al., 2019) unequivocally show the findings on VA and/or EER in many other countries, showing the densification and globalization of knowledge on the subject. Levy at al. (2019) highlight the sharp increase in the total number of empirical publications on VA models since 2002. Among the 370 articles forming the corpus, 253 (68%) were conducted in the USA, 46 (12%) in the UK, and 71 (19%) in the remaining 24 countries covered by the review. Of these 71 studies, 50 were conducted in a European Union (EU) member country. Levy et al. (2019; Table A4) found that 14% of studies were from Germany, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Slovakia, Spain, France, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Sweden. Only three articles focused on Portugal or Spain. Everson (2017) examines VA modelling for educational accountability, focusing on methodological challenges in estimating teacher or school effects. The study highlights three key concerns: (1) research often overlooks critical issues raised by theorists and critics, (2) interactions between different issues and assumption violations remain understudied, and (3) fundamental challenges in VA modelling persist, requiring deeper reflection on its philosophical foundations. Among the 82 studies reviewed, only three address EER in Portugal or Spain, though experience and academic networks suggest a much larger body of original research.

As shown above, since its inception, EER has been associated with the purpose of ensuring quality and equity in education. Yet, more than 50 years later, it remains a largely unknown field of research in many countries, including Portugal and Spain. In fact, even within Portugal and Spain, there is limited awareness of the scope, characteristics, findings, and potential of EER and VA studies for educational improvement, policy, and practice. Moreover, the challenges and limitations of these studies, which still need to be addressed, provide significant research opportunities for the next generation of educational researchers.Limited knowledge is a key obstacle to the development of science across all fields, but it is especially impacting education, where science for policy plays a crucial role for achieving social justice.

This article aims to fill this gap and contribute to the EER literature by examining the current state of scientific research on EER or VA conducted by researchers affiliated with Spanish and Portuguese institutions. Considering the impact of collaborative networks between Portuguese or Spanish authors and researchers from Portuguese- or Spanish-speaking countries, the dissemination of knowledge through this article also contributes to advancing EER in countries where it has yet to gain prominence. The analysis is designed to support scholars, early-career researchers, and policymakers better understand the field´s evolution, identify key milestones, and recognize patterns in knowledge growth and dissemination over time. In doing so, it also aims to highlight trends for future research and provide evidence-based insights for policy and practice. To achieve these goals, the study is guided by three research questions that map the scientific contributions:

- What is the landscape of knowledge production represented by the corpus?

- What authors and articles have had the greatest scholarly impact on the education literature?

- What is the content and intellectual structure of the knowledge ?

Answering the question 1 involves mapping and analyzing the distribution, structure, and trends within the corpus. A descriptive analysis is conducted in order to analyze the distribution of publications over time, identifying periods of increased or decreased productivity; to identify the most prolific journals within the corpus; to identify key authors, their contributions, and collaborative networks.

Answering the question 2 involves analyzing citation patterns that is identifying the authors and articles with the highest citation counts, as they are typically the ones with the greatest impact.

To answer question 3, it is necessary to uncover the main conceptual foundations of the corpus by identifying the key concepts and models that underpin it. This is achieved by analyzing key works from question 2, tracking changes in intellectual structure, identifying emerging trends and shifts, and mapping research clusters and study contexts.

Methods

This scoping review examined the corpus, enabling science mapping to identify knowledge production patterns through bibliographic metadata, unlike meta-analysis or qualitative synthesis, which integrate research findings (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The process of collecting scientific articles that meet the purposes of this study unfolded as follows. Firstly, the automatic selection carried out with the following query in the Scopus indexed database, was conducted. This database was selected as it is trustworthy bibliometric data sources for large scale knowledge assessments (Baas et al., 2020), broadly covering the topic.

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "growth curve" OR "growth model" OR "value added" OR "value-added" OR "school effectiveness" OR "educational effectiveness" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( multilevel OR hierarchical ) AND PUBYEAR > 1999 AND SUBJAREA ( soci ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( AFFILCOUNTRY , "Spain" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( AFFILCOUNTRY , "Portugal" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) )

The same is to say that we searched in title, abstract, and keywords for articles on "value added" or "value-added" or "growth curve" or "growth model" or “school effectiveness” or “educational effectiveness”, which also include "multilevel" or "hierarchical", were published since January 2000, whose authors were affiliated to Spanish or Portuguese organizations, and journals’ subject area is social sciences. This automated selection process yielded 42 research articles. Next, based on abstract screening, five articles were deemed out of scope and excluded. A full-text analysis confirmed these exclusions, resulting in a final corpus of 37 articles. In this regard, the included articles describe scientific research that cumulatively meets the following criteria:

- SER as conceptual framework, in particular regarding value-added (VA) model or growth model;

- Authored or coauthored by scientists affiliated to Portuguese or Spanish organizations;

- Published in a peer-reviewed journal indexed in Scopus between 2000 and 2024.

- Available with a complete manuscript in Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, or English;

- Title, abstract, and keywords available in English.

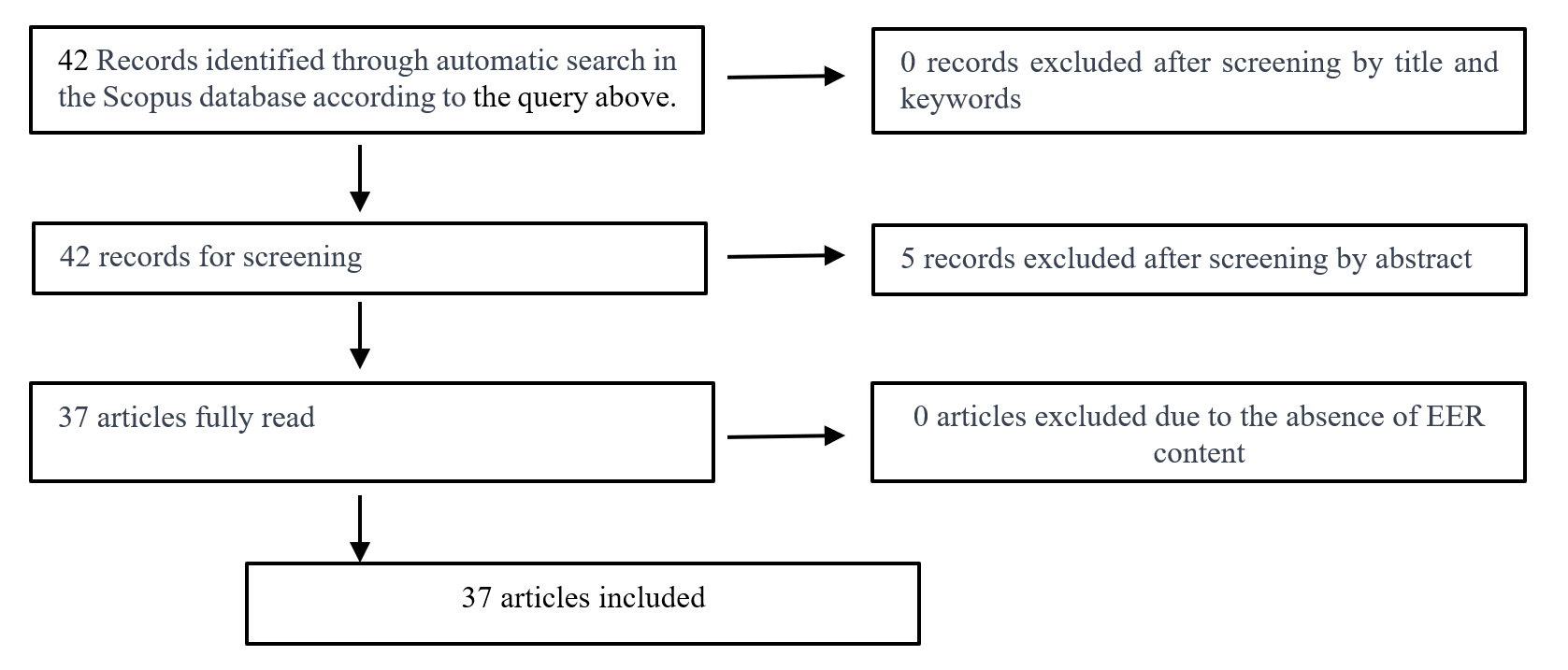

Diagram I presents a flowchart outlining the study selection process. Data file in *.csv format is available as supplementary material, allowing for reproducibility or further analyses. In other words, making it possible to reanalyze these data, using the same methods to get the same results; allowing for replicability, potentially conducting to a new study.

DIAGRAM I. Flowchart of the article selection process

Source: Compiled by the authors

The analyses were conducted in two sequential steps: firstly, a bibliometric approach; second, the content analyses of article clusters. Bibliometric analysis was performed using Bibliometrix, a comprehensive science mapping software package for R (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017). Thematic analysis is conducted using the authors’ keywords, with a thesaurus of synonyms enabled. For example, ´value-added´ is consistently used over ´value added,´ and ´hierarchical linear model´ is preferred over variations such as ´hierarchical linear models,´ ´hierarchical linear modeling,´ or ´hierarchical linear modelling’.

Results

Landscape of knowledge production represented by the corpus

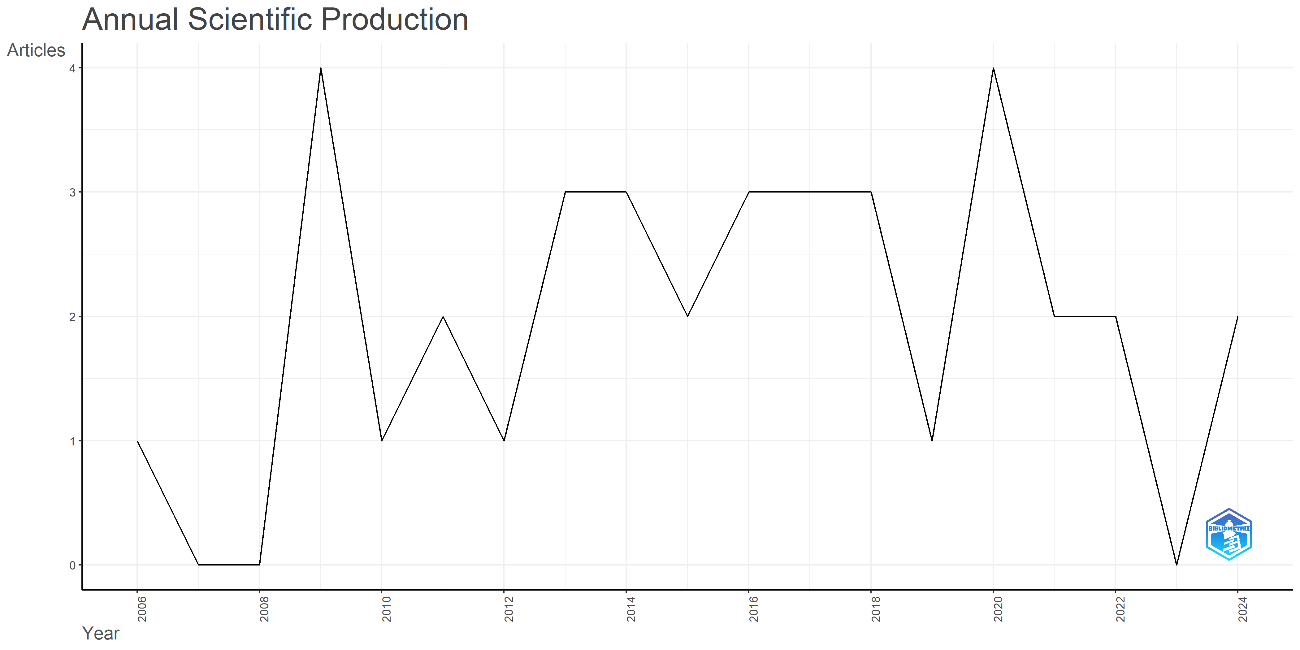

Although the search was conducted after 1999, the corpus spans from 2006 to 2024 and includes 37 articles published in 24 different source titles. The annual production varies from 0 to four papers (Figure I). The total number of authors is 73, with 32.4% involving international co-authorship. On average, there are 2.8 authors per article and 4 papers are single-authored. The number of author’s keywords is 118.

FIGURE I. Annual trend of number of articles

Source: Compiled by the author

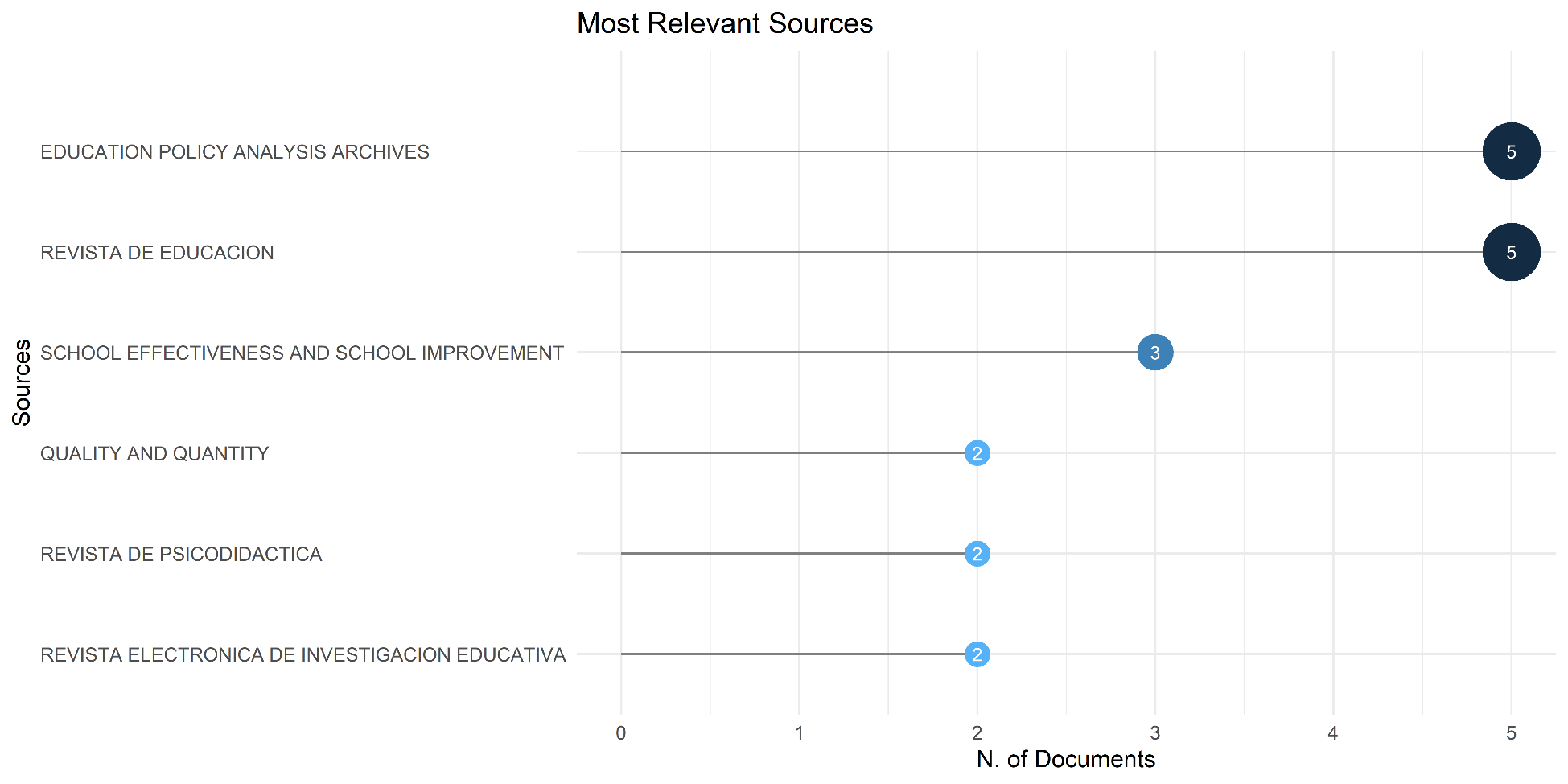

FIGURE II. Most relevant sources

Source: Compiled by the author

Six source titles published 51% of the corpus,while the remaining 18 articles were published in 18 different source titles. According to Bradford’s law, the core sources are Education Policy Analysis Archives, Revista de Educación, School Effectiveness and School Improvement (Figure II). Among the six most representative source titles in the corpus, four are either multilingual or publish in two languages, Spanish or English. The majority of the articles were published in journals that use languages other than English, with 10.8% in Portuguese and 51.4% in Spanish. The remaining 37.8% articles were published in English. Regarding the disciplinary classification of the source titles, Education represents 95% of the corpus. For the purpose of this study, we used the classification of journals according to the Scopus area/category.

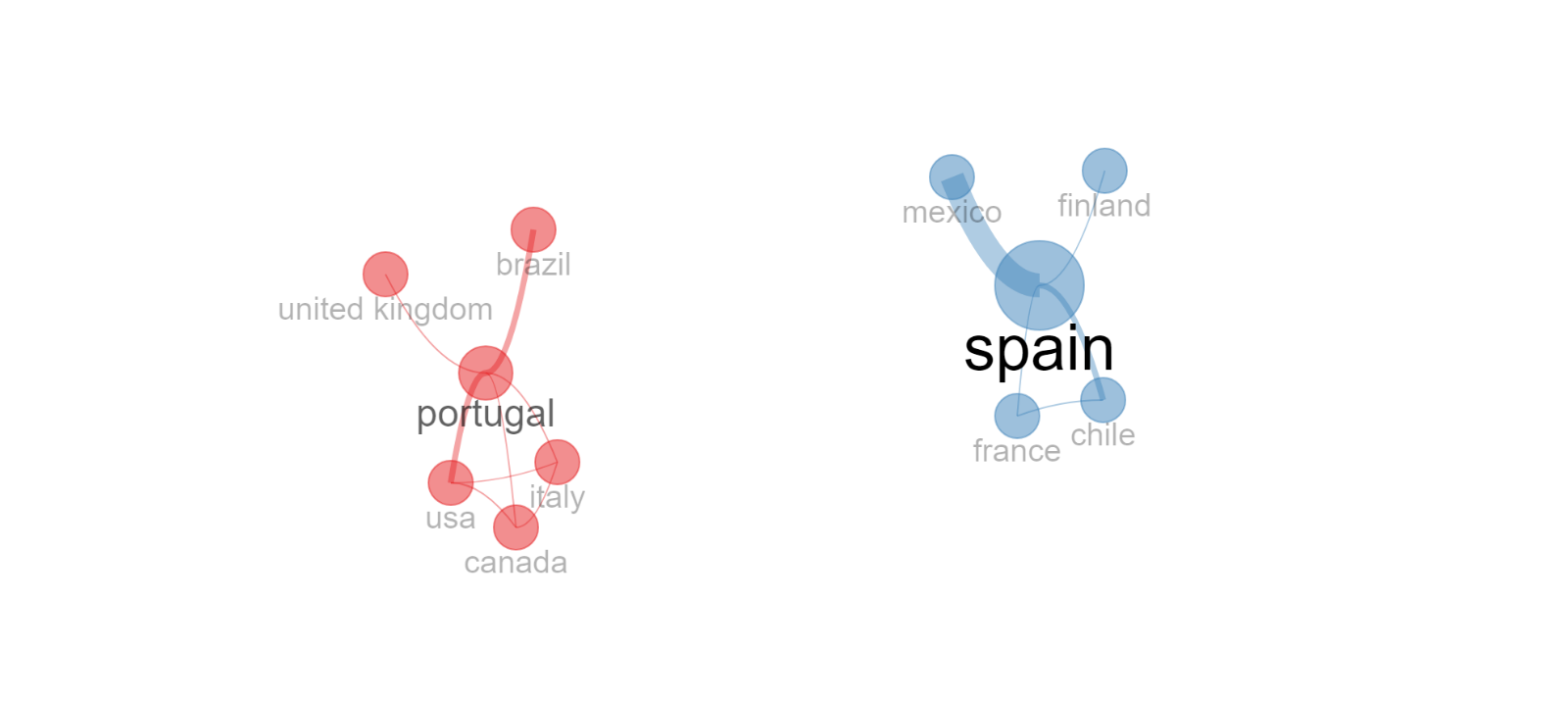

FIGURE III. Country collaboration network

Source: Compiled by the authors

The country collaboration network (Figure III) reveals two distinct clusters of authorship with no connections between them. The left-hand cluster consists of Portuguese-affiliated authors collaborating with researchers from the USA, Canada, Italy, Brazil, and the UK, while the right-hand cluster features Spanish-affiliated authors working with colleagues from Finland, Mexico, France, and Chile. These two clusters had no connections, indicating no collaborative network between Portugal and Spain.

Authors and articles with the greatest scholarly impact

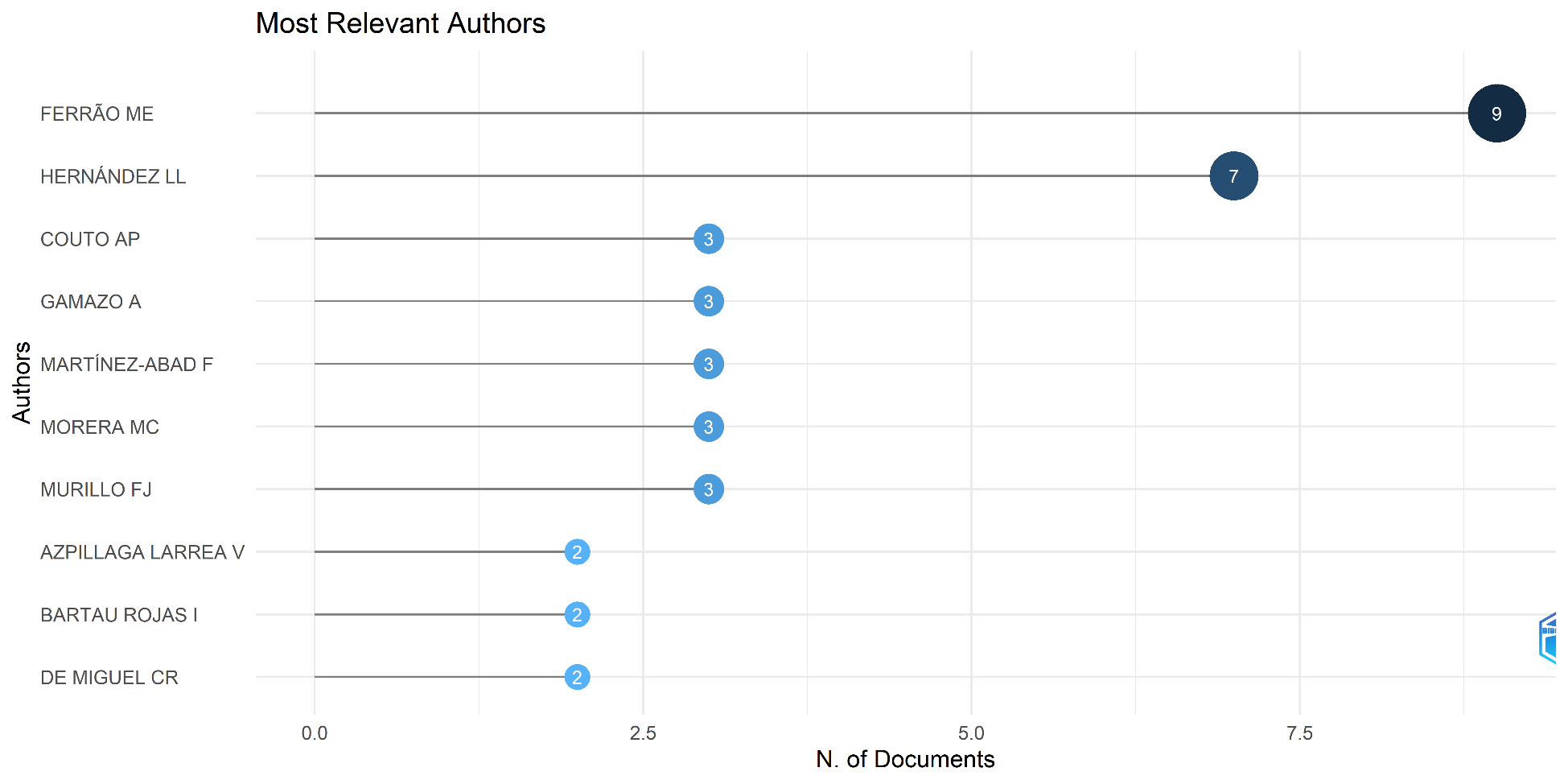

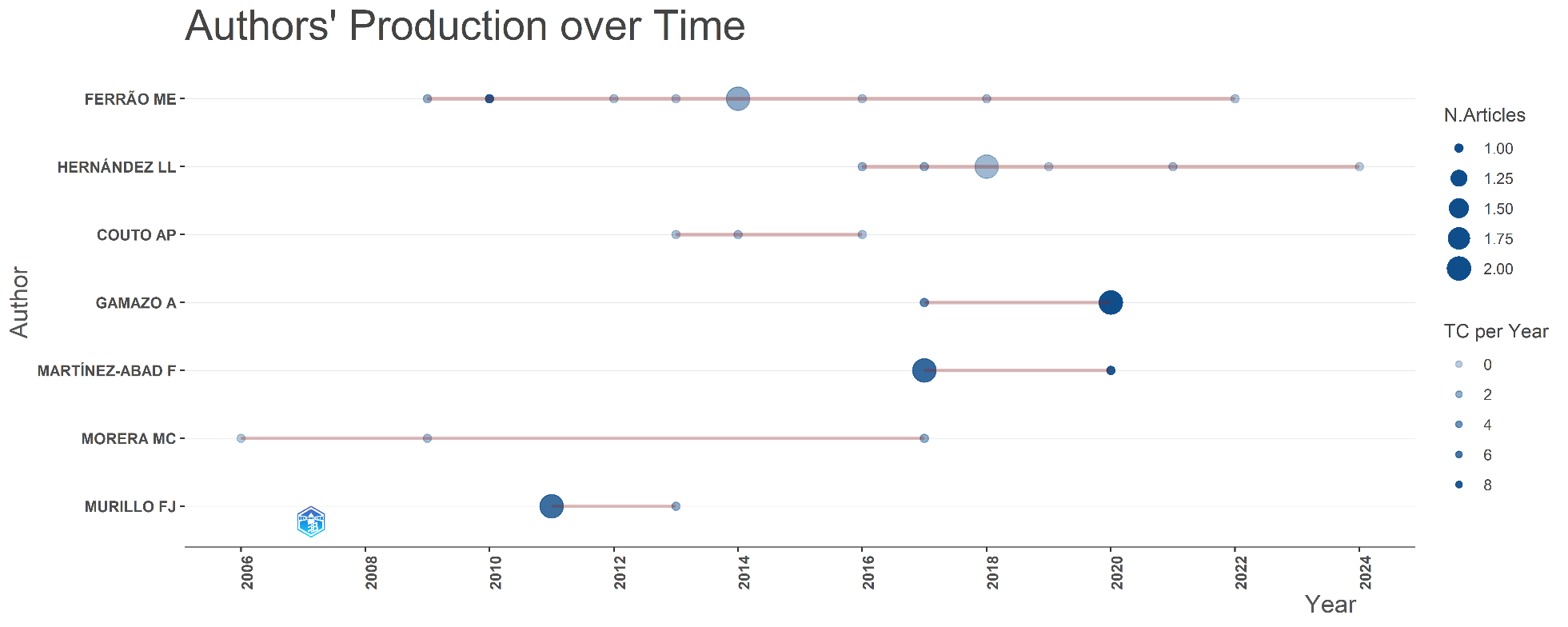

Seven authors have written or co-written at least three papers in the corpus (Figure IV). Among the 73 authors, only three have publications spanning more than five years. Most authors either contribute sporadically to the field or primarily collaborate within different co-authorship networks and research themes (Figure V).

FIGURE IV. Most relevant authors

Source: Compiled by the authors

FIGURE V. Authors’ production over time

Source: Compiled by the authors

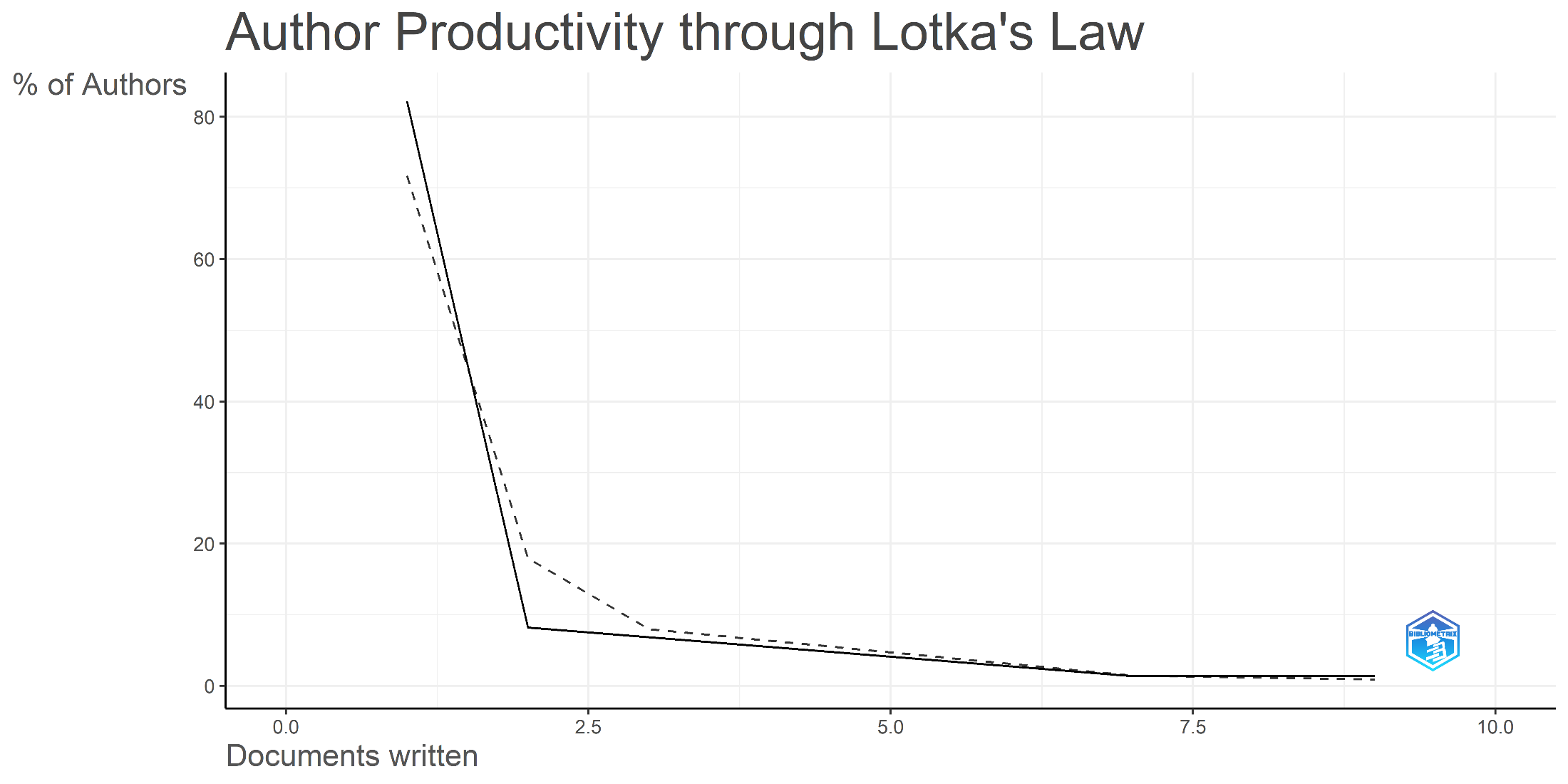

As shown in Figure VI, approximately 90% of the authors have contributed to at most two papers in the corpus. The other collaborative networks each consist of fewer than eight members. This graph illustrates Lotka´s law, which describes the distribution of scientific productivity among authors. The law states that a small number of authors contribute a disproportionately large number of papers, while the majority of authors contribute few. In Figure 6 can be observed that the number of papers written by an author ranges from 1 to 9, with the number of papers increasing as you move right in the horizontal axis. In turn, the Y-axis (% of Authors) shows the percentage of authors contributing a certain percentage of papers. The higher the percentage on the y-axis, the larger the group of authors contributing that number of papers. The graph characterizes by a steep decline at the start, since it starts very high on the left (near 90%) and drops sharply, meaning that the majority of authors (around 80-90%) have written very few papers of the corpus — likely 1 or 2. Then, a flattening curve meaning that, as the curve moves to the right, representing authors who have written more papers, the percentage of authors contributing steadily decreases and levels off near 0%. This suggests that only a small percentage of authors (6%) have contributed three or more papers, with an even smaller number producing a substantial body of work.

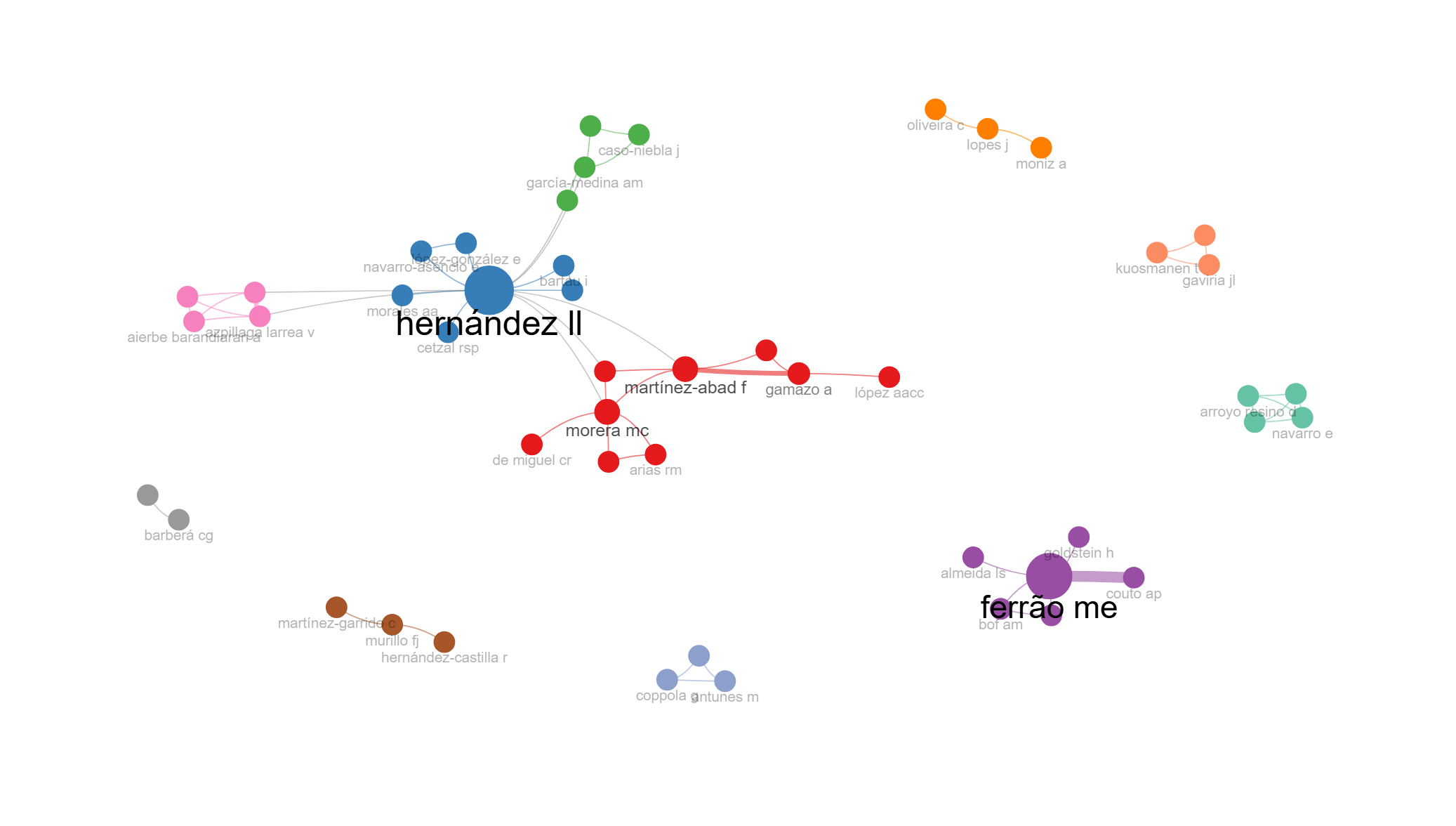

The collaboration network (Figure VII) reveals a strong cluster, highlighted in blue, centered around Hernandez L.L., who has direct or indirect scientific connections with 23 authors, most of them consisting of three clusters highlighted in red, green and pink.

FIGURE VI. Author productivity through Lotka’s law

Source: Compiled by the authors

FIGURE VII. Collaboration network (Authors)

Source: Compiled by the author

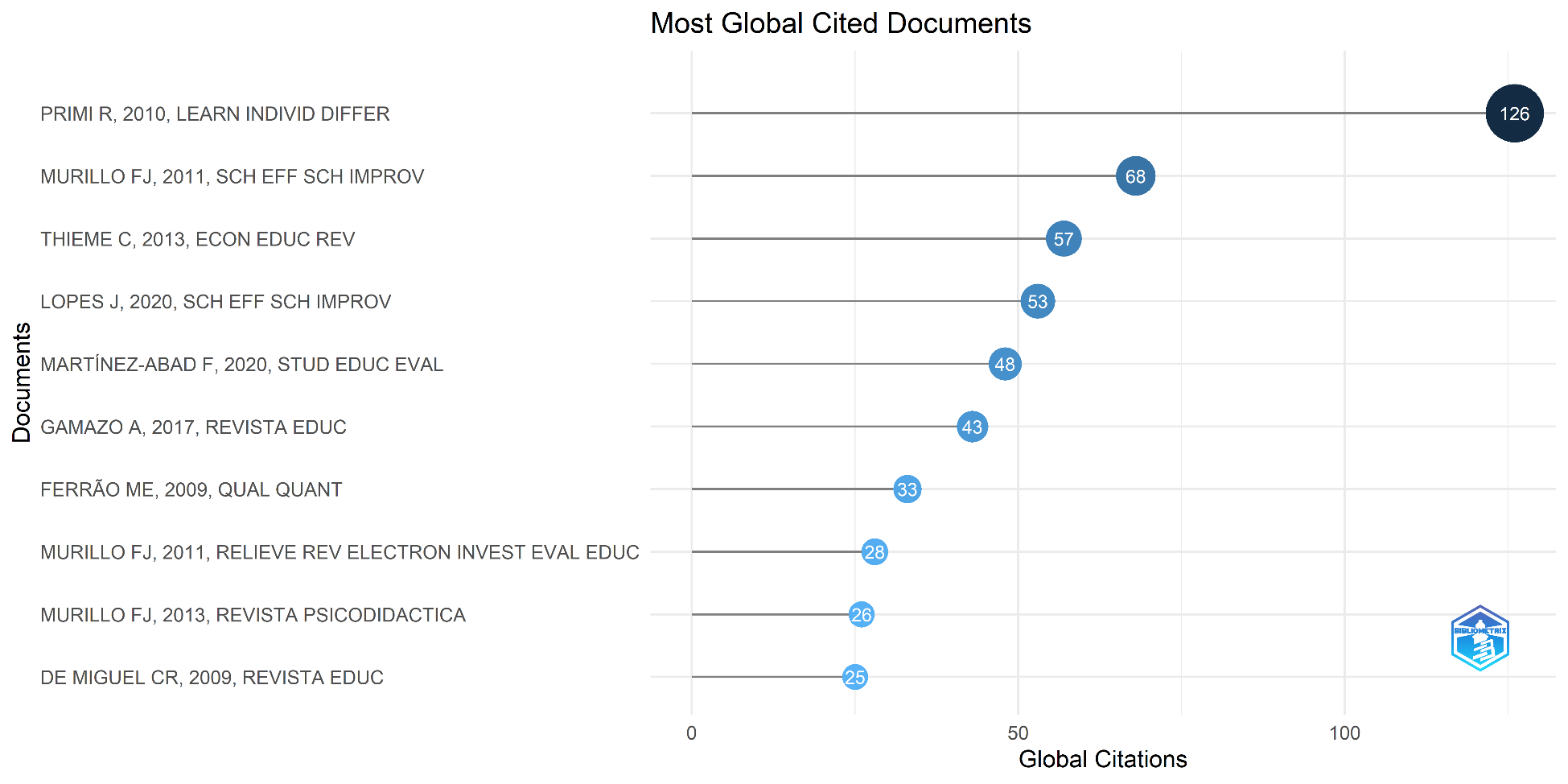

FIGURE VIII. Most global cited articles

Source: Compiled by the authors

The content analysis of the 10 most global cited articles (Figure VIII) shows that they collectively investigate various factors influencing school effectiveness, student achievement, and teacher job satisfaction, using diverse methodologies like multilevel modeling, decision trees, and frontier approaches.

The content and the intellectual structure of the knowledge

The corpus covers several educational and social contexts, including the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Brazil, Chile, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain. It also includes articles that allow for the characterization and comparison of education in Latin American countries (Martínez-Garrido, 2017; Murillo & Martínez-Garrido, 2013; Murillo & Román, 2011) like Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Chile, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Dominican Republic and Venezuela. Some studies using international large-scale assessment (ILSA) data analyze multiple countries, with a primary focus on OECD members. There is an impressive number of articles on the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country (Blanco et al., 2009; Hernández et al., 2016; Larrea et al., 2021, 2023; Morales et al., 2019). In analyzing the content of the corpus, specific characteristics were selected for the purposes of this study, grouped into six main categories: (1) Methodological and data quality requirements; (2) The education level targeted by the study; (3) The statistical unit used for inference; (4) The purpose of the VA approach; (5) The analyses of clusters of co-occurrence network; (6) Intellectual structure of the knowledge over time.

Methods and data quality requirements

By search design, all of papers use multilevel and/or growth models. Approximately 19% of the studies utilize ILSA data from the PISA, TIMSS, or TALIS surveys. Among the remaining studies, 52% employ longitudinal data, some of them have standardized or vertically aligned outcome scales. Most articles either provide a detailed description of the instruments and scale properties used or cite other works where these descriptions are thoroughly developed. Approximately 65% of studies consider mathematics performance as outcome variable, 40% consider performance in reading, and 35% consider both. Some studies consider non-cognitive student outcome variables (Murillo & Hernandez-Castilla, 2011; Santos et al., 2020) and Often statistical models that account for variables like prior achievement (in studies with longitudinal data) and socioeconomic status (SES) or similar proxies are applied. The corpus include articles with innovative methodological approaches such as VA based on growth curves with polynomial terms (Lopez-Martin et al., 2014), VA models adjusted for measurement errors (Ferrão & Goldstein, 2009), or educational performance based on nonparametric frontier methods (Thieme et al., 2013).

Level of education focused on in the study

Most articles refer to primary (ISCED 1) or elementary education (ISCED 2). They are mostly studies with empirical bases obtained from a representative sample of a clearly defined target population. For example, Murillo and colleagues (Murillo & Hernandez-Castilla, 2011; Murillo & Román, 2011) studied primary education in several Latin American countries, showing that while infrastructure and resources influence math and reading achievement, their impact varies across countries, underscoring the critical role of local context. Also Thieme et al. (2013) highlight the role of resources in Chilean primary education. Primi et al. (2010) tracked Cova da Beira students aged 11–14 over two years, testing them in math four times to examine the role of fluid intelligence in academic growth throughout elementary education. Other articles based on the Cova da Beira longitudinal study (Ferrão, 2009, 2012a; Ferrão & Couto, 2014; Ferrão & Goldstein, 2009) include participants from several grades from primary to lower secondary (ISCED 3) education. The longitudinal study conducted by Lopes et al. (2015) involves 2nd and 3rd grade students. The VA growth multilevel model for reading comprehension proposed by Lopez-Martin et al. (2014) is successfully tested in primary and secondary education students in Madrid. PISA-based studies (Arroyo-Resino et al., 2024; Gamazo et al., 2018; Lopez & Gamazo, 2020; Martínez-Abad et al., 2020; Miguel, 2009; Miguel & Castro-Morera, 2006) focus on 15-year-old students, most of whom are in secondary education. The study by Travitzki et al. (2016) refers to Brazilian candidates to higher education studies.

Focus on Teacher or School unit

The percentage of papers that apply multilevel regression or hierarchical linear models is 95%, with students as unit of analysis, nested in classrooms or schools. Teacher and teaching practices are central to the research objectives of Murillo and Martínez-Garrido (2013), who use value-added approach to assess the influence of homework, and Lopes and Oliveira (2020) and Martínez-Garrido (2017), who examine teacher job satisfaction. The articles focused on the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country (Blanco et al., 2009; Hernández et al., 2016; Larrea et al., 2021, 2023; Morales et al., 2019) deal with topics addressing the relationship between school effectiveness and gender equality, schools as learning organizations and the focus on teacher training, and the relationship between education in values and school effectiveness. With the exception of Primi et al. (2010) and Lopes at al. (2015), articles in Portugal are directly related to common themes in VA in Europe. They address topics such as the selection of predictor variables and the consequences of that selection, the use of the VA model for improving education, the impact of measurement error on VA estimates, or the characteristics of research on school effectiveness in Portuguese-speaking countries, comparing the value-added model with the contextualized results model. In this regard, we can affirm that the analyzed corpus suggests that the VA model, in its multiple specifications, has been investigated in the Iberian Peninsula with a primary focus on improving the educational systems and holding the school accountable for inference.

Purpose or Objective of the VA Model

Building upon the previous analysis, the studies predominantly highlight the relevance of the VA model for school improvement (which includes enhancing student learning and development) and for the educational system evaluation, providing contributions to the educational assessment system. In general, the VA methodology is designed for diagnostic and educational improvement purposes (Ferrão, 2014; Ferrão & Couto, 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2018; Zúñiga et al., 2018), as well as for analyzing differential effectiveness, educational quality, and equity (Ferrão, 2022; Ferrão et al., 2018; Ferrer-Esteban, 2016), including proposals that classify schools as high- or low-performing (Castro-Morera & Pedroza-Zuñiga, 2015; García-Jiménez et al., 2022; Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2021; Martínez-Abad et al., 2017). None of the articles advocate for the adoption of VA for high-stake purposes for teachers or schools.

Clusters of co-occurrence network

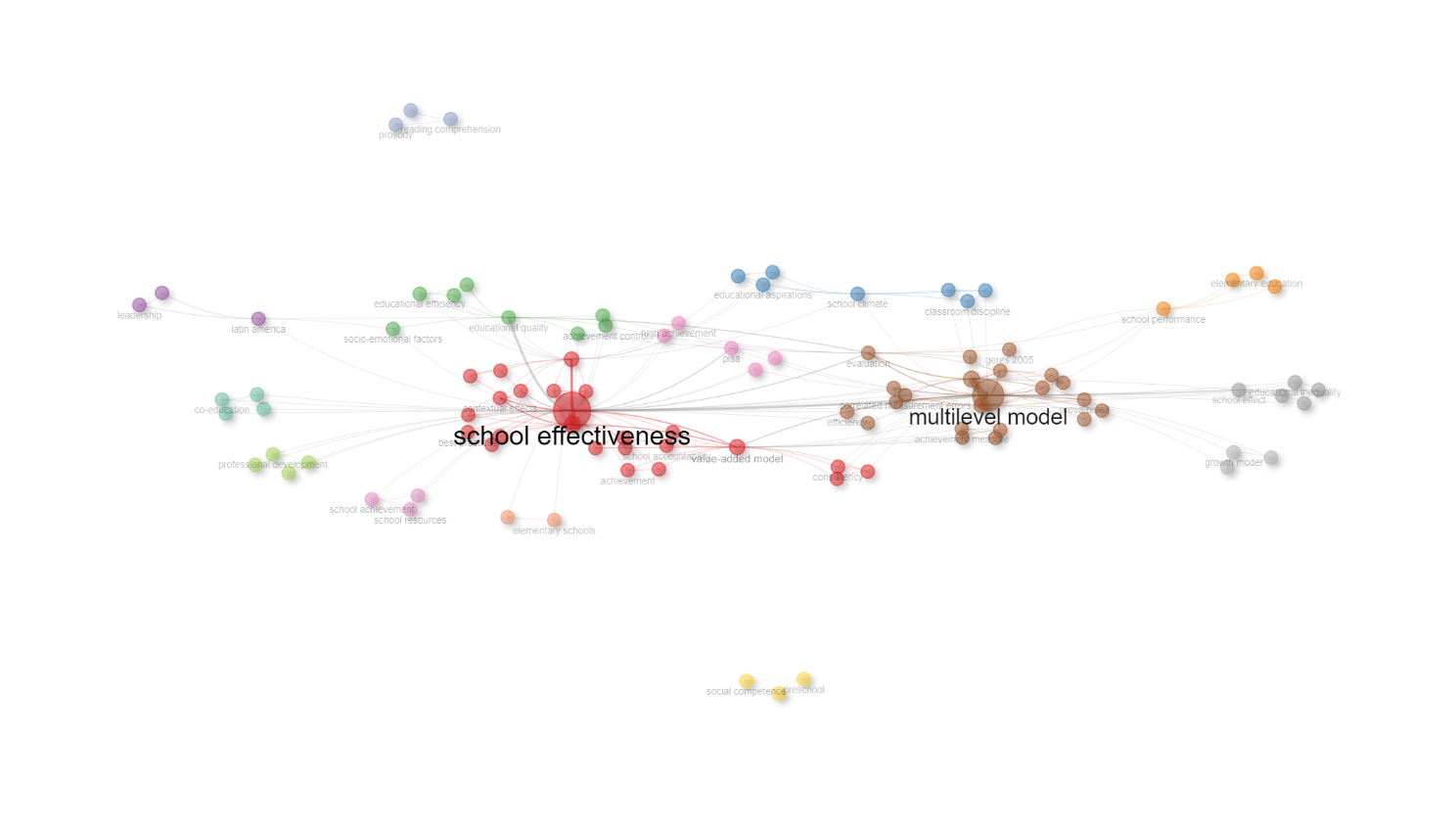

The term "intellectual structure" usually refers to the underlying organization, relationships, and key themes or concepts that emerge from the corpus under analysis. We did it by analyzing the clusters of co-occurrence network that is based on authors’ keywords. The resulting diagram is presented in Figure IX, and shows several distinct interconnected clusters within the research corpus, each centered on key EER relevant themes. For this study, we selected the three clusters with the highest number of nodes: the School Effectiveness cluster (red), the Multilevel Model cluster (brown), and the Educational Quality cluster (green).

School Effectiveness Cluster (red): This cluster revolves around concepts aimed at improving school performance and quality. Keywords like "best practices", “effective schools research”, “contextual effects”, “sense of belonging”, “academic achievement”, "educational assessment", “teaching”, “teacher education” point to strategies for enhancing teaching and learning. The inclusion of “large-scale assessments”, "PISA", "value-added model" and “linear and quadratic growth model” indicates a connection to international benchmarks and methodologies for measuring educational effectiveness. The keywords like “consistency”, “stability”, “school assessment”, “school effects”, and “school accountability” highlight the central focus of the School Effectiveness cluster, emphasizing themes related to evaluating and improving the performance and outcomes of schools. These keywords suggest a strong emphasis on measuring institutional effectiveness, ensuring accountability, and maintaining stable educational standards. This cluster reflects a commitment to identifying and implementing effective educational practices, particularly in diverse contexts such as Latin America (Chile and Mexico).Multilevel Model Cluster (brown): This cluster emphasizes complex analytical frameworks used to assess educational outcomes. Keywords like "achievement measure", and "differential effectiveness" highlight a focus on measuring student success across various dimensions, while terms such as "educational inequality", “social equity”, “longitudinal study” and "growth model" suggest an interest in understanding how different factors influence equity and educational performance over time. This cluster indicates a nuanced approach to evaluating educational interventions and their impact on diverse populations. Specifically, fluid intelligence, through cognitive abilities (Numerical, Abstract, Verbal, and Spatial Reasoning), is strongly linked to initial math achievement and the rate of improvement over time. The topic of educational evaluation and its purpose are present through the keywords “evaluation”, “school/teacher effectiveness”, “school/teacher accountability”, “school/teacher improvement”. The keywords “latent variable multidimensionality,” “item response theory”, “measurement error”, “correlated measurement errors,” and “reliability” are central to the Multilevel Model cluster, indicating a focus on advanced statistical techniques used to analyze complex educational data. These terms suggest a strong emphasis on the precision and reliability of measurement models, particularly in assessing latent traits and addressing errors in data interpretation within hierarchical or multilevel structures. Educational Quality Cluster (green): Focusing on the social and emotional aspects of education, this cluster includes keywords like "educational quality", "achievement control", "educational efficiency", "educational evaluation", "high schools", "school success", and "student evaluation". These terms highlight the focus on assessing and improving various dimensions of education, including the effectiveness of schools, student performance, and the impact of both cognitive and socio-emotional factors on academic success, particularly in high school settings.

In general, the diversity of themes addressed contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of educational success factors across different educational systems and cultural environments.

FIGURE IX. Co-occurrence network (Author’s keywords)

Source: Compiled by the authors

Intellectual structure of the knowledge over time

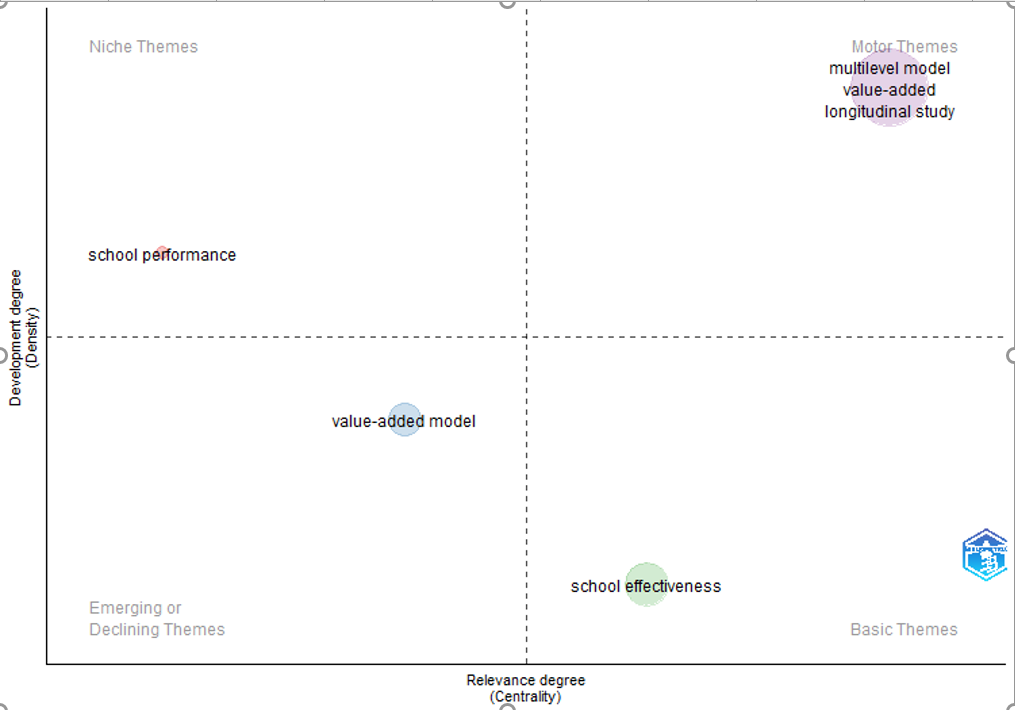

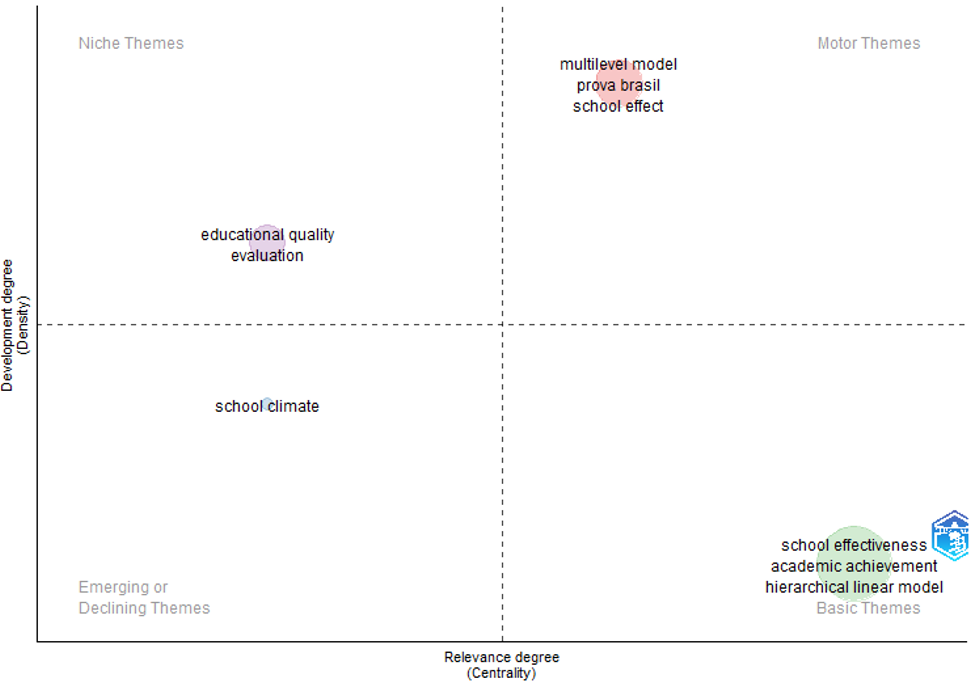

Having identified influential authors and papers that shape the field, the EER foundational concepts, framework issues and how they are interconnected, we will present and describe the thematic evolution network map in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of how research themes evolve over time. The study period is divided into two distinct time slices (period 1 – 2006 to 2014; period 2 -2015 to 2024) to observe changes. The thematic evolution includes four main clusters in each period, each strongly related to the clusters above presented.

FIGURE X. Thematic evolution, 2006-2014

Source: Compiled by the authors

Source: Compiled by the authors

As observed in Figure X, the first period of research is marked by themes like multilevel model, value-added and longitudinal study as motor themes, it also includes school performance as niche theme. While in period 2, includes educational quality evaluation,

school climate, and school effect assessed by Prova Brasil.

The thematic evolution of EER shows a shift in focus. In the first period (2006–2014), themes like multilevel models, value-added approaches, and longitudinal studies were central, with a strong emphasis on school performance. By the second period (2015–2024), attention shifted toward educational quality evaluation, school climate, and assessments like Prova Brasil, indicating a broader focus on both the academic and environmental factors that influence educational outcomes. Ultimately, the intellectual structure of EER has evolved, with foundational concepts becoming more interconnected and diverse. The field has transitioned from a heavy focus on school performance and statistical models toward a more nuanced consideration of educational quality, accountability, and socio-emotional factors, reflecting the dynamic nature of educational research over time.

FIGURE XI. Thematic evolution, 2015-2024

Source: Compiled by the authors

Conclusion

This paper makes a significant contribution to the field of Educational Effectiveness Research (EER) by mapping the contributions of Portugal and Spain to the value-added in education from 2000 to 2024. Utilizing advanced bibliometric analysis and co-citation methods, the study provides an overview of the knowledge production, revealing the thematic and methodological trends that have emerged over the past two decades.

By addressing the research questions, the paper identifies key authors and seminal articles that have shaped the discourse on value-added models in education, highlighting their impact on both regional and international scholarly conversations. The corpus features 32% international authorship, with 9% of authors contributing three or more papers. This pattern suggests a lack of continuity in international networks over time. Furthermore, it elucidates the intellectual structure of knowledge within the field, tracing how conceptual frameworks and research methodologies have evolved over time.

This research enhances the understanding of how value-added approaches are perceived and implemented in the educational contexts of Portugal and Spain. It also contributes to the broader Educational Effectiveness Research (EER) literature by providing insights from Spanish (51%), English (38%), and Portuguese (11%) publications, highlighting regional contributions that have often been overlooked. This review consolidates and analyzes existing research, incorporating studies in Portuguese (11%) and Spanish (51%). Notably, 89% of these articles remain uncited in recent English-language reviews. From the selection of 37 articles, only four have been cited in recent review articles on the field (Everson, 2017; Levy et al., 2019). Considering that the most recent literature review (Levy et al., 2019) mentions 26 countries with scientific production of 370 articles, and only 14% refer to European Union (EU27) countries, the 37 articles studied here make a decisive contribution to the development of the thematic as a scientific agenda.

In most studies, mathematics is the chosen dimension to quantify the students’ cognitive development. The majority (95%) of studies based on EER-specific data collection demonstrate a high degree of rigor in meeting the criteria for instrument validation and scale adjustment for academic outcomes, indicating in-depth knowledge of the specific methodological requirements of school effectiveness studies. In general, the statistical models include students´ prior achievement and socioeconomic status (SES) or a proxy, and other predictors. Such characteristics differ from most studies conducted in other regions. For example, Levy (2019) refers to 85% of the analyzed corpus as including prior achievement as a covariate, while only 2% include noncognitive predictors of achievement. Some articles´ empirical evidence is based on international large-scale surveys, such as PISA, TALIS and TIMSS, which use cross-sectional data by design. In these cases, prior achievement as a control variable is absent from the EER models. The ISCED 1 level of education is the most studied. Perhaps due to the demanding methodological requirements, none of the studies fully represents the universe at stake in the two countries, suggesting a significant opportunity for future educational research agenda.

Our results also suggest that the VA model, in its various specifications, has been investigated in the Iberian Peninsula with a primary focus on improving the educational system, reinforcing school autonomy, and enhancing the role of educational assessment in the cycle of public policies. None of the articles advocates for the adoption of VA for high-stakes purposes. Teachers and teaching practices make a difference. The evidence of differential effectiveness among schools supports the promotion of programs and measures aimed at enhancing schools and the broader educational system. However, the corpus suggests a general consensus that holding teachers or schools accountable using methodologies that fail to accurately assess their quality may do more harm than good (Everson, 2017).Our findings serve as a foundation for future research, encouraging a more nuanced exploration of educational effectiveness that integrates both local and global perspectives. Moreover, there remains a substantial need for further scientific research in the Iberian Peninsula to identify the key characteristics of effective teaching practices and factors that contribute to educational effectiveness.

The corpus reveals a slower pace of development and publication in Portugal and Spain compared to other regions (Murillo & Martinez-Garrido, 2019; Scheerens, 2014). It emphasizes the link between educational assessment and school improvement, along with key issues of quality and equity in education. While highlighting the region’s existing knowledge and capacity, it also reveals the lack of investment in large-scale projects. However, implementing a value-added indicator system depends on the quality and quantity of variables used in the model, making governmental collaboration essential(Ferrão, 2012b). Since the 1990s, there has been significant progress in addressing statistical methodology issues, enabling more rigorous analysis and clearer interpretation of both individual student and school academic achievements (Saunders, 1999) These advancements have shed light on the intrinsic complexity of the challenges involved in evaluating educational effectiveness that, according to the intellectual structure of corpus’ knowledge, in less than 20 years of VA research conducted by Portuguese and Spanish scholars, the major methodological challenges have been effectively tackled and resolved. Our findings indicate that, over time, the intellectual structure of EER has evolved, with foundational concepts becoming increasingly interconnected and diverse. The field has shifted from a strong emphasis on school performance and statistical models to a more comprehensive approach that considers educational quality, accountability for improvement, and socio-emotional factors, highlighting the dynamic nature of educational research.

Finally, the international perspective of this research highlights the strong global connections Portuguese and Spanish scholars have fostered, albeit separately. Such diverse international engagement points out the growing recognition of EER conducted in Iberia on a global scale. It also shows how both Portugal and Spain have become part of broader research ecosystems, collaborating across continents. However, despite these global links, the absence of collaboration between Portuguese and Spanish researchers signals a missed opportunity for regional knowledge exchange. Strengthening cross-border networks within the Iberian Peninsula could further integrate both countries into the global research community and foster solutions tailored to their shared educational challenges. Thus, to enhance the impact of EER and VA measures in Portugal and Spain, it is crucial to establish stronger collaborative networks between researchers in both countries. The absence of a collaborative link between Portuguese and Spanish scholars limits the exchange of ideas, best practices, and innovations in the field, potentially hindering the development of evidence-based educational policies. Policymakers should prioritize the creation of formal research partnerships, joint academic programs, and cross-border funding opportunities. By fostering collaboration between these two clusters, researchers can collectively address shared educational challenges, improve the quality of research, and develop region-specific solutions that enhance educational outcomes in both countries. This will also lead to greater integration of Southern European perspectives into the global EER dialogue, ensuring more inclusive and effective educational policies and practices.

This study has the limitation of mapping the topic based solely on articles indexed in Scopus, which, despite having the highest number of source titles in Portuguese and Spanish compared to the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Web of Science, may still exclude relevant studies from other sources.

Acknowledgements and funding

Maria Eugénia Ferrão thanks anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions, and the Bristol School in Covilhã for professional translation from English to Spanish. The author was partially supported by CEMAPRE/REM—UIDB/05069/2020 FCT/MCTES through national funds.

Referencias bibliográficas

Las referencias al corpus están marcadas con un asterisco.

AERA-American Educational Research Association. (2015). AERA

Statement on use of value-added models (VAM) for the evaluation of

educators and educator preparation programs.

Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for

comprehensive science mapping analysis.

*Arias, R. M., & Soto, J. G. (2009). Concepto y evolución de

los modelos de valor añadido en educación.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a

methodological framework.

*Arroyo-Resino, D. A., Constante-Amores, A., Castro, M., &

Navarro, E. (2024). School effectiveness and high reading achievement

of Spanish students in PISA 2018: A machine learning approach.

Baas, J., Schotten, M., & Plume, A. (2020). Scopus as a

curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research

in quantitative science studies.

Ballou, D., Sanders, W., & Wright, P. (2004). Controlling for

student background in value-added assessment of teachers.

*Blanco, Á. B., Barberá, C. G., & Ordóñez, X. G. (2009).

Patrones de correlación entre medidas de rendimiento escolar en

evaluaciones longitudinales: Un estudio de simulación desde un enfoque

multinivel.

Braun, H. (2005). Value-added modeling: What does due diligence

require? In R. Lissitz (Ed.),

Bryk, A. S., & Weisberg, H. I. (1976). Value-Added analysis: A

dynamic approach to the estimation of treatment effects.

*Castro-Morera, M., & Pedroza-Zuñiga, L. H. (2015). Escuelas de

Alto y Bajo Valor Añadido. Perfiles Diferenciales de las Secundarias

en Baja California.

Creemers, B. P. M. (2006). The importance and perspectives of

international studies in educational effectiveness.

Creemers, B. P. M. (2007). Educational Effectiveness and

Improvement: The Development of the Field in Mainland Europe.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2015). Can value added add value to teacher

evaluation?

Everson, K. C. (2017). Value-added modeling and educational

accountability: Are we answering the real questions?

Ferrão, M. E. (2009). Sensibilidad de las especificaciones del

modelo de valor añadido: Midiendo el estatus socioeconómico

[Sensitivity of value-added model specifications: Measuring

socioeconomic status].

*Ferrão, M. E. (2012a). On the stability of value added indicators.

Ferrão, M. E. (2012b). Avaliação educacional e modelos de valor

acrescentado: tópicos de reflexão.

*Ferrão, M. E. (2014). School effectiveness research findings in

the Portuguese speaking countries: Brazil and Portugal.

*Ferrão, M. E. (2022). Longitudinal study on differential

effectiveness and social equity in Brazil.

*Ferrão, M. E., Barros, G. T. F., Bof, A. M., & Oliveira, A. S.

(2018). Estudo longitudinal sobre eficácia educacional no Brasil:

Comparação entre resultados contextualizados e valor acrescentado

[Longitudinal study on educational effectiveness in Brazil: Comparing

contextualised results and value added].

*Ferrão, M. E., & Couto, A. (2013). Value-added indicator and

topics on consistency and stability: An application to Brazil.

*Ferrão, M. E., & Couto, A. P. (2014). The use of a school

value-added model for educational improvement: A case study from the

Portuguese primary education system.

*Ferrão, M. E., & Goldstein, H. (2009). Adjusting for

measurement error in the value added model: Evidence from Portugal.

*Ferrer-Esteban, G. (2016). Trade-off between effectiveness and

equity? An analysis of social sorting between classrooms and between

schools.

*Gamazo, A., Martínez-Abad, F., Olmos-Migueláñez, S., &

Rodríguez-Conde, M. J. (2018). Assessment of factors related to school

effectiveness in PISA 2015. A multilevel analysis.

*García-Jiménez, J., Torres-Gordillo, J.-J., &

Rodríguez-Santero, J. (2022). Factors associated with school

effectiveness: Detection of high- and low-efficiency schools through

hierarchical linear models.

Goldstein, H. (1997). Methods in school effectiveness research.

*Gonzalez, L., Ramirez, C., Hernández, L. L., & Garcia-Medina,

A. (2018). Eficacia escolar y aspiraciones educativas en el

bachillerato.

Gray, J., Jesson, D., Goldstein, H., Hedger, K., & Rasbash, J.

(1995). A multi-level analysis of school improvement: Changes in

schools’ performance over time.

Hanushek, E. (1971). Teacher characteristic and gains in student

achievement: Estimation using micro data.

*Hernández, L. L., Bereziartua, J., & Bartau, I. (2016).

Pre-primary and primary teacher training and education Inservice

teacher education in highly effective schools.

Kyriakides, L., & Creemers, B. P. M. (2008). A longitudinal

study on the stability over time of school and teacher effects on

student outcomes.

*Larrea, V. A., Rojas, I. B., Barabdiaran, A. A., & Intxausti,

N. (2021). Teacher training and professional development in accordance

with level of school effectiveness.

*Larrea, V. A., Rojas, I. B., & Hernández, L. L. (2023). Mejora

escolar y coeducación en centros de secundaria de la comunidad

autónoma vasca: Implicaciones para la orientación educativa [A school

improvement and coeducation in secondary schools in the basque

autonomous community].

Levy, J., Brunner, M., Keller, U., & Fischbach, A. (2019).

Methodological issues in value-added modeling: An international review

from 26 countries.

Longford, N. T. (2012). A revision of school effectiveness

analysis.

*Lopes, J., & Oliveira, C. (2020). Teacher and school

determinants of teacher job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis.

*Lopes, J., Silva, M. M., Moniz, A., Spear-swerling, L., &

Zibulsky, J. (2015). Prosody growth and reading comprehension: A

longitudinal study from 2nd through the end of 3rd grade.

*Lopez-Gonzalez, E., Navarro-Asencio, E., Pedro, M., Hernández, L.

L., & Tourón, J. (2021). A study of school effectiveness in

primary schools using hierarchical linear models.

*Lopez-Martin, E., Kuosmanen, T., & Gaviria, J. L. (2014).

Linear and nonlinear growth models for value-added assessment: an

application to Spanish primary and secondary schools’ progress in

reading comprehension. In

*Lopez, A., & Gamazo, A. (2020). Multilevel study about the

explanatory variables of the results of Mexico in PISA 2015.

*Martínez-Abad, F., Gamazo, A., & Rodriguez-Conde, M.-J.

(2020). Educational data mining: Identification of factors associated

with school effectiveness in PISA assessment.

*Martínez-Abad, F., Hernández, L. L., & Morera, M. C. (2017).

Selección de escuelas de alta y baja eficacia en Baja California

(México).

*Martínez-Garrido, C. (2017). Satisfacción Laboral de los Docentes

en América Latina.

*Miguel, C. R. (2009). Las escuelas eficaces: Un estudio multinivel

de factores explicativos del rendimiento escolar en el área de

matemáticas.

*Miguel, C. R., & Castro-Morera, M. (2006). Un estudio

multinivel basado em PISA 2003: Factores de eficacia escolar en el

area de matemáticas.

*Morales, A., Hernandez, L. L., & Rojas, I. B. (2019). Hábitos

y valores del alumnado en centros de primaria de alta eficacia

escolar.

Morganstein, D., & Wasserstein, R. (2014). ASA Statement on

Value-Added Models.

Mortimore, P. (1991). The nature and findings of research on school

effectiveness in the primary sector. In S. Riddell & S. Brown

(Eds.),

Murillo, F. J. (2003). Una panorámica de la investigación

iberoamericana sobre eficacia escolar.

*Murillo, F. J., & Hernandez-Castilla, R. (2011). School

factors associated with socio-emotional development in Latin american

countries.

Murillo, F. J., & Martinez-Garrido, C. (2019). Una mirada a la

investigacion educativa em América Latina a partir de sus artículos [A

look at educational research in Latin America from its papers].

*Murillo, F. J., & Martínez-Garrido, C. (2013). Incidencia de

las tareas para casa en el rendimiento académico. Un estudio con

estudiantes iberoamericanos de Educación Primaria.

*Murillo, F. J., & Román, M. (2011). School infrastructure and

resources do matter: analysis of the incidence of school resources on

the performance of Latin American students.

OECD. (2008).

Plewis, I. (1997). Terminology and definition in multilevel models

analysis.

*Primi, R., Ferrão, M. E., & Almeida, L. S. (2010). Fluid

intelligence as a predictor of learning: A longitudinal multilevel

approach applied to math.

Ray, A., McCormack, T., & Evans, H. (2009). Value added in

english schools.

Reynolds, D., Sammons, P., De Fraine, B., Van Damme, J., Townsend,

T., Teddlie, C., & Stringfield, S. (2014). Educational

effectiveness research (EER): a state-of-the-art review.

Sammons, P., Davis, S., & Gray, J. (2016). Methodological and

scientific properties of school effectiveness research. In

*Santos, A. J., Daniel, J. R., Antunes, M., Coppola, G., Trudel,

M., & Vaughn, B. E. (2020). Changes in preschool children ’ s

social engagement positively predict changes in social competence : A

three ‐ year longitudinal study of portuguese children.

Saunders, L. (1999). A brief history of educational “value added”:

How did we get to where we are?

Scheerens, J. (2014). School, teaching, and system effectiveness:

Some comments on three state-of-the-art reviews.

Strand, S. (2011). The limits of social class in explaining ethnic

gaps in educational attainment.

Strand, S. (2016). Do some schools narrow the gap? Differential

school effectiveness revisited.

*Thieme, C., Prior, D., & Tortosa-ausina, E. (2013). A

multilevel decomposition of school performance using robust

nonparametric frontier techniques.

Thomas, S., Kyriakides, L., & Townsend, T. (2016). Educational

effectiveness research in new, emerging, and traditional contexts. In

C. Chapman, D. Muijs, D. Reynolds, P. Sammons, & C. Teddlie

(Eds.),

*Travitzki, R., Ferrão, M. E., & Couto, A. P. (2016).

Educational and socio-economic inequalities of pre-university

Brazilian population: A view from the ENEM data.

*Zúñiga, L. P., Cetzal, R., & Hernandez, L. (2018). Criterios

para la identificación y selección de escuelas eficaces de nivel medio

superior [Criteria for the Identification and Selection of Effective

High Schools].

Información de contacto / Contact info: Maria Eugénia Ferrão. Universidade da Beita Interior, Faculdade de Ciências, Departamento de Matemática. E-mail: meferrao@ubi.pt