To thrive or drift? Youth in transition between secondary education institutions and second-chance schools

¿Derivar o ir a la deriva? Jóvenes en transición entre institutos de educación secundaria y escuelas de segunda oportunidad

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-693

María José Chisvert-Tarazona

Department of Didactics and School Organization of the University of Valencia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5533-8100

Davinia Palomares-Montero

Department of Didactics and School Organization of the University of Valencia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3671-2195

Maribel García Gracia

Department of Sociology of the Autonomous University of Barcelona

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6521-0437

Rafael Merino Pareja

Department of Sociology of the Autonomous University of Barcelona

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1430-9853

Abstract

Reducing the rate of early school leaving continues to be a priority for educational systems. This article involves an analysis of the transition of young people after their failure in the formal education system towards second-chance schools (SCE), how their profiles are constructed, how educational trajectories are determined, and the role of educational agents involved in these processes in the Spanish context. The aim of this work is to understand how transitions between these educational institutions and their underlying logic are articulated, as well as the coordination and supposed bidirectionality in students’ trajectories. The methodology is based on a qualitative approach and the triangulation of agents and instruments. Twenty-four semistructured interviews were conducted with SCE management officials, and nine interviews were conducted with tutors or counsellors at secondary education institutions (SEIs). Six discussion groups were subsequently held with 47 educators and six discussion groups with 56 young people from 24 SCEs. The results indicate that these young people hold different perspectives from those of educational agents. SEI teachers focus to a greater extent on individual factors, such as demotivation, ruptures, and conflict, whereas SCE professionals have a more holistic and comprehensive view of young people, incorporating reflections on their social and contextual conditions. Notably, the logic of coordination between institutions does not always prevail. Young people and their families rarely participate in decision-making regarding their own trajectories upon their premature departure from an SEI. In some cases, referral and externalization are imposed in the SEI. Finally, some unintended effects of educational policies are identified, as well as some divergences in their application at the regional level, which provide elements for reflection.

Keywords:

Dropout, unqualified young people, secondary education, educational transitions, Second Chance Schools

Resumen

Reducir la tasa de abandono escolar temprano continúa siendo una prioridad para los sistemas educativos. Este artículo analiza la transición de jóvenes tras su fracaso en el sistema educativo formal hacia las escuelas de segunda oportunidad (E2O), cómo se construyen sus perfiles, cómo se deciden las trayectorias educativas y el papel de los agentes educativos que intervienen en estos procesos en el contexto español. El objetivo del trabajo es comprender cómo se articulan las transiciones entre estas instituciones educativas y sus lógicas subyacentes, así como la coordinación y supuesta bidireccionalidad en sus trayectorias. La metodología parte de una aproximación cualitativa y la triangulación de agentes e instrumentos. Se han realizado 24 entrevistas semiestructuradas a responsables de dirección de las E2O y 9 entrevistas a tutores u orientadores de institutos de educación secundaria (IES). Con posterioridad se realizaron 6 grupos de discusión en los que han participado 47 educadores y 6 grupos de discusión que contaron con 56 jóvenes, de 24 E2O. Los resultados apuntan diferentes miradas de los agentes educativos al analizar el perfil de estos jóvenes. El profesorado de SEIs focaliza en mayor grado en factores individuales: la desmotivación, las rupturas y el conflicto; mientras que los profesionales de E20 tienen una visión más holística e integral del joven, incorporando reflexiones sobre su estigmatización. Se constata que no siempre prevalece una lógica de coordinación entre instituciones. Los jóvenes y sus familias apenas participan en la toma de decisiones de sus propias trayectorias a su salida prematura del IES. De hecho, en algunos casos se impone en los SEIs la derivación y externalización. Por último, se identifican algunos efectos no deseados de las políticas educativas y algunas divergencias en la aplicación de estas a nivel autonómico que aportan elementos para la reflexión.

Palabras clave:

Abandono de estudios, jóvenes sin cualificación, enseñanza secundaria, transiciones educativas, Escuelas de Segunda OportunidadIntroduction

The current education system expands entry and exit points, making access to training more flexible to compensate for inequalities on the basis of socioeconomic origin. Along these lines, the European Strategy attributes relevant roles in smoothing educational transitions, reducing early school leaving, and meeting the needs of a knowledge-based economy to education, vocational training, and guidance (European Commission et al., 2014).

In 2023, 13.6% of students left school early (INE, 2024). Although this rate has decreased significantly in the last decade, it is still far from the 9% proposed by the European Union in the Europe 2030 Strategy. It is a prolonged process, the result of a trajectory of disconnection and educational failure that, in many cases, begins in early childhood (Dupéré et al., 2015; Samuel & Burguer, 2020).

Solís and Blanco (2014) introduce two features of educational progression to explain social stratification. On the one hand, vertical stratification refers to school continuity or disenrolment during the transition between educational levels. On the other hand, horizontal stratification refers to selection processes that generate inequality when placed in different educational modalities and institutions. These training pathways are designed to externalize academic failure (Rujas, 2020).

Additionally,

European youth at risk of vulnerability accumulate negative experiences in the educational system and typically have limited access to economic, cultural, and social capital (Scandurra et al., 2020). However, these inequalities do not stem exclusively from limited resources. Transitions are inherent in educational policies (Rawolle & Lingard, 2008) and articulate unequal meanings and opportunities beyond the dominant discourses of choice and individualization (Cuconato & Walther, 2015). Both institutional structures and individual biographical orientations affect educational trajectories (Walther et al., 2015), leading to early externalization on the part of students. Young people who recompose their identity consider transition a reasonable option and even an individual choice (Rujas, 2020).

From an interactionist perspective, the choice is the result of complex negotiations between young people and other referents, especially families and teachers, generating different levels of action and creating meaning (Cuconato & Walther, 2015). The complexity of these processes creates uncertainties and requires good coordination among centres, teachers and families, as well as a school culture that is attentive to their needs. Identifying, analysing, questioning and coconstructing alternatives to segregation is a collective task (Collet et al., 2022).

Walther et al. (2015) identify five trajectory patterns, i.e.,

configurations of structure and agency, in youth educational

transitions. Two are clearly linked to these groups: (1)

The welfare state is based on a firm belief in universal education and its ability to reduce and/or eliminate social inequalities (Barr, 2020). However, the conditionality of the social rights of young people at risk of social exclusion is evidenced by the state’s favouring of an activation approach to study and work that amplifies individual responsibility and reduces state and political responsibility (Morel et al., 2013).

Reforms highlight policies that seek to reverse early school leaving and address transitions to work or other training, not at the time students are leaving the system but before they complete their schooling (Morentin & Ballesteros, 2024). It is important not to limit the study of transitions to formal educational stages, given that less formalized contexts can be key to educational re-engagement and labour market integration. An example is the second-chance school (SCE), which offers an educational outlet to those who drop out of the educational system, enabling school continuity and reducing the risk for these young people, who begin to consider options for educational re-engagement and labour market integration (Marhuenda-Fluixá & Chisvert-Tarazona, 2022; Palomares-Montero et al., 2024).

SCEs, promoted by third-sector entities, are foundations, associations, cooperatives, or platforms. They are characterized by pedagogical flexibility, adapting their methodology to serve young people at risk of exclusion, and offering personalized training paths that combine academic training with job skills. In contrast, secondary education (SEI) are regulated by Organic Law 3/2020 on Education, which requires a more rigid and standardized curriculum. Although the regulated education system promotes equity and inclusion, its traditional structure may not be suitable for students who have dropped out of school (Palomares-Montero et al., 2024).

The Spanish SCE Association

Table I. Specific objectives and initial assumptions

| Specific objective | Initial assumptions |

|---|---|

Examine who is involved in decision-making in two-way transitions between SEIs and SCEs. |

|

Analyse the institutional articulation between SEIs and SCEs. |

|

Understand the effect of Spanish educational policies as a structural determinant in transitions. |

Note: Compiled by the authors

Method

The qualitative methodological approach analyses the experiences of educational agents and organizations in their natural and historical context, accessing a "reality" constructed and interpreted by those who inhabit it (Flick, 2004). This inductive process allows access to tacit knowledge from diverse information-gathering techniques on different agents participating in the journeys of these young people to holistically understand the subject of analysis on the basis of the triangulation of instruments and participants.

The starting theoretical perspective is symbolic interactionism. It analyses how individuals create and modify meanings through communication and social interaction, providing a unique perspective for understanding how they make sense of their social environment and construct their identity (Sosa-Sánchez, 2021).

Participants and Instruments

Participants and Instruments

Semistructured interviews were conducted with

24

For the semistructured interviews, a script adapted to the profile of the interviewee was designed to address organizational, curricular, and orientation issues. For the focus groups, two semistructured scripts were developed, one for young people and one for educators. The first recapitulated the interviewee’s experience prior to the SCE and the transition to it, comparing its teaching and learning process with that of the SEI. The second addressed the processes of access, reception, training, and intermediation/referral at the end of the process, as well as issues related to the direction and management of the SCE, drawing on the prior analysis of the interviews. The instruments allowed for the inclusion of emerging questions to delve deeper into the interviewees’ responses and provide credibility by revealing contrasting beliefs among them (Guba & Lincoln, 1998).

Procedure

Field work took place between 2021 and 2023, with online interviews conducted between March and June 2021 and in-person focus groups conducted between October and November 2023 in six host SCEs. The research enabled the collection of information from semistructured interviews for subsequent verification through focus groups (Guba, 1983).

The research team established a two-phase protocol. The first phase provided an approximation of reality: i) consultation of the SCEs’ institutional websites (March 2021); ii) semistructured interviews with SCE directors (April–May 2021); and iii) semistructured interviews with tutors/counsellors in the SEIs that referred students to and/or received referrals from SCEs (June 2021). The broader research continued while the interim reports were being prepared. In the second phase, to ensure the confirmability of the interpretations, iv) focus groups were held with educational teams and young people (October–November 2023), allowing the prior information to be supplemented with other stakeholders and the credibility of beliefs to be contrasted. The progressive development of the research provided consistency by identifying traceable factors that give meaning to information collection (Guba, 1983).

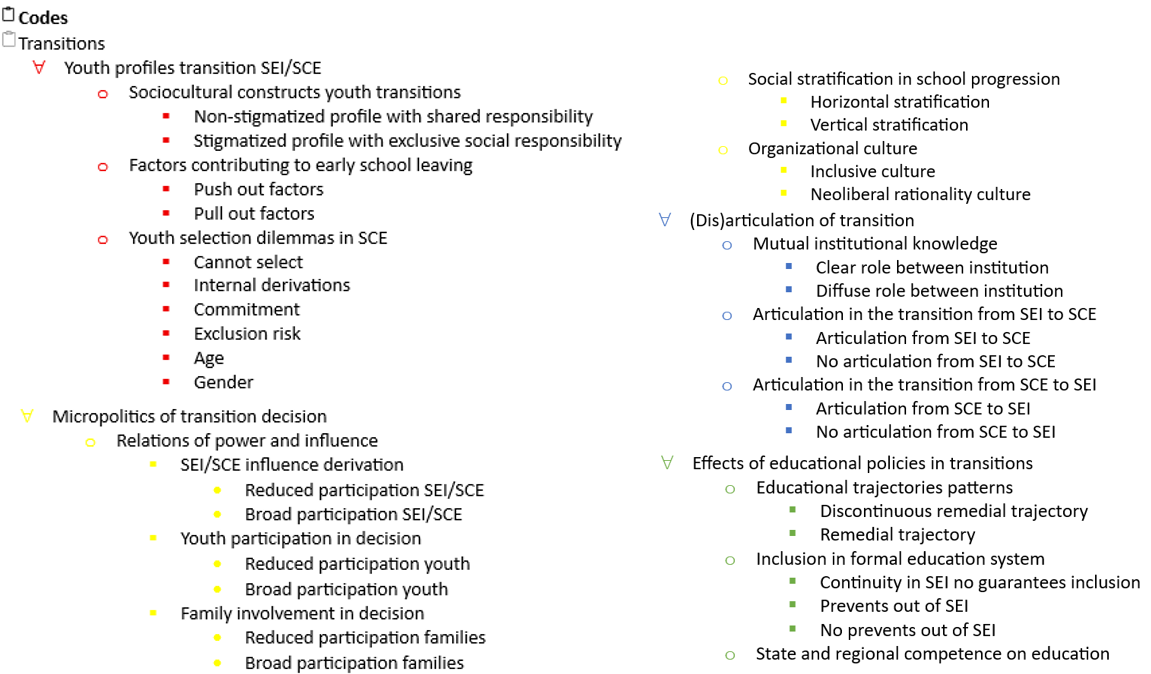

A priori axial coding was used, combined with emergent categories. Initial assumptions were generated, and the participating educational institutions were described to enable transferability to similar contexts. The reviewed transcripts were analysed using MAXQDA Plus 2022 on the basis of dimensions and categories (Figure 1), which demonstrated the confirmability of the data.

Figure 1. Dimensions and Categories of Analysis

Note: Compiled by the authors. Maxqda Plus 2022

A concordance analysis was performed using Cohen´s kappa measure. The results of the calculations revealed that in 71.9% of the cases, both evaluators agreed (Po = 0.719), and the probability of agreement by chance was 24.9% (Pe = 0.249). With the calculated Cohen´s kappa coefficient (K = 0.63), it is concluded that the concordance between the researchers is substantial (Landis & Koch, 1977).

The codes for anonymizing the responses vary by the technique applied, type of institution, and reporting agent. They include code E for the type of institution—SCE or SEI—and, for the reporting agent, D for members of the management team and OT for tutors and guidance counsellors: E_SCE_Dx and E_SEI_OTx. For the focus groups, the code GD is used, followed by SCE and the agent´s identification (E for educator and J for youth): GD_SCE_Ex and GD_SCE_Jx.

Results

Constructs on the profiles of young people who move to/from SCEs

The sociocultural profile constructs of youth who move between SEI

and SCEs show dissonance in both individual and broad contextual

factors. The factors that generate educational dropout (

Table II. Profiles of young people who move from SEIs to SCEs

| Category | Subcategories | Analysis | Research 1 | Research 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs of the sociocultural profiles of young people who move between SEIs and SCEs | Dissonances in the construct | Stigmatized profile of the young person with almost exclusive responsibility (Morel, Palier and Palme, 2013) | 23 | 23 |

| No stigmatized profile of the young person with shared responsibility | 29 | 28 | ||

| Factors in educational abandonment (Nes, Demo & Ianes, 2017; NESE, 2009) among young people who transition to SCEs | Desire to work, peer expectations regarding SCEs | 9 | 9 | |

| Low socioeconomic status, migration or ethnic minority origin and/or problematic school careers | 7 | 7 | ||

| Dilemma of youth selection in SCEs | Age, gender, risk of social exclusion and commitment | 47 | 46 | |

Note: Compiled by the authors

Young people who transition from secondary schools to other secondary education have experienced previous disruptions in their educational journeys. These are deviations from linear trajectories that result from institutional regulations, poor performance, behavioural problems, disaffection with the school, and/or conflicts with teachers. Three young people expressed this:

I also failed, because I repeated the ESO, and I repeated it again, but since I couldn´t repeat it again... (GD_SCE_J2: 26).

(…) I didn’t study anything. I just didn’t like it (GD_SCE_J5: 239).

At school, I had a bad temper; I fought with the teachers (GD_SCE_J1: 416).

These ruptures are also marked by life paths. Tutor teachers and guidance staff at secondary schools consider these young people “conflictive, with profiles that are sometimes very unmotivated, because they have a very complex personal history (...) with many difficulties” (E_SEI_OT4: 6). They allude to the fragility of the young people’s mental health: “it is very vulnerable and therefore full of stress, anxiety, anguish and insomnia, (...) personal and psychological suffering” (E_SEI_OT6: 3). They mention that the young people may be from low-income families and/or immigrants: “Humble, working-class people from the neighbourhood, along with a very large enrolment of migrant students” (E_SEI_OT6: 2). They are students who, in the formal educational context, “do not trust school at all” (E_SEI_OT6: 8) and who experience “disaffection towards learning” (E_SEI_OT6: 3).

The SCEs distance themselves from the stigma of considering them as bad, conflictive students and warn of the need to delve deeper into the reasons for their difficulties in school:

(…) Normally these kids, bad students, that is, “I have all the possibilities in the world and I haven’t wanted to study,” very few. (…) There’s always something else behind it and that’s where you have to get to … (E_SCE_D32: 105).

Some of these kids come here with anger towards everything (…) because no one has stopped to tell them, “Anyway, you´re not doing things that badly” (E_SCE_D7: 19).

SCE educators question the labelling produced by the institutions that derives from the following:

(…) the vast majority come from other entities and…, it is true that they label us: “well they are like this, they are like that”. Our job is to try not to place those labels on them (GD_SCE_E6: 131).

While the educators also emphasize the students’ cognitive development, in some cases, they work with young people diagnosed with disabilities, and in others, they identify disabilities upon the students’ arrival:

(…) you come across many profiles, sometimes also undiagnosed profiles, but that could be (E_SCE_D21: 30).

The young people do not always have basic needs met, such as the right to decent housing, with significant implications for the pedagogical relationship:

When you have children sleeping on the street, you can´t say "at 6, I close the blinds, I go home and I forget" (GD_SCE_E2: 136).

Educational teams note differences in the students’ age at arrival. When they are younger, "it´s very difficult for them to make that journey. They´re here because they don´t want to continue studying. They´re unable to see beyond that" (E_SCE_D5: 259).

They are

A gender gap is also evident when students enter SCEs: "there are fewer women than men" (GD_SCE_E5: 16). Educational teams justify this by citing reasons related to training supply and demand, as well as contextual factors. They believe that, in many cases, the family context places women in the private sphere, where "training is not necessary" (GD_SCE_E1: 98). One young woman expressed this:

(…) I come from an environment where a woman’s worth is for the house, the children and all that, and to get to this moment and be able to do something more, be able to work in something else… (GD_SCE_J5: 343).

SCE schools’ selection processes are crucial in defining the profile. The regulations explicitly state that these schools are aimed at young people "aged 15–30 who have not completed compulsory secondary education" (E_SCE_D2: 4) and are therefore "at risk of social exclusion" (E_SCE_D16: 11). Economic difficulties are also highlighted: "their unique economic situation is key" (E_SCE_D2: 4). Sometimes they exclude young people by requiring prior knowledge "such as attending a literacy school first" (E_SCE_D17: 70). SCE that offer vocational training courses do not participate in their selection processes: "it´s given to us, we don´t select" (E_SCE_D24: 139).

The educational teams all note the need for commitment from entering students, “really seeing the motivation” (GD_SCE_E6: 31), justifying “betting on people who are looking for a new opportunity” (E_SCE_D2: 4). However, they are not exempt from pressure to produce results that perhaps force them to “demonstrate the efficiency of the project to the funder” (E_SCE_D17: 109). In certain programs, it is “very demanding and forces you, almost in the selection of young people, to say ´hey, if this one is going to leave me after two days, I´m not going to take him.´ It´s very perverse” (E_SCE_D17: 109).

Tutors and counsellors at secondary schools assess young people when they return after their time at an SCE school. This assessment differs from their initial assessment, highlighting their greater maturity and responsibility in their work: "I find them very formal, very hard working" (E_SEI_OT5: 5). However, we find cases without differentiated follow-up for students arriving from SCEs (education to vocational training): "It´s a vocational training program; here, it´s about everyone entering through the same system" (E_SEI_OT2: 7). Additionally, horizontal stratification is evident in transitions to workshop schools: "They are programs specifically designed for those people" (E_SEI_OT2: 6).

On the other hand, SCE educators see a clear “evolution or opening and also increasing effort and success stories” (GD_SCE_E5: 19) in the youth who participate in their schools and complete the training programme: the vertical stratification is softened by new transitions after their time in SCEs.

Young people express the profound change they have experienced after participating in SCEs, which have broadened their educational, professional, and relational expectations and aspirations:

Now I am finishing my high school diploma, and apart from that, I want to take more courses (GD_SCE_J3: 197).

Fights with my parents, fights in the street, (…) I joined [SCE name] and look, the relationship with my family is perfect. I´m very happy (…). I´m getting what I have to get out of it (GD_SCE_J2: 142).

They are young people who do not fit into the formal education system, establishing a relationship of mutual distrust, but who find acceptance and support in SCEs, which generates positive feelings towards education, largely determined by how SEI teachers and educators describe these young people: “I accompany you in this process of improving your skills, it is realizing where you have to be and the itinerary can last a year or two, what the young person needs” (E_SCE_E34: 29).

Micropolitics in the decision to transition between SEIs and SCEs

Different actors intervene in the decision to transition, make decisions about the transition, and influence the ability of youth to overcome their initial situation, which leads to educational abandonment (Table III).

Table III. Micropolitics in the decision to transition

| Category | Subcategories | Analysis | Research 1 | Research 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power and influence relations between educational agents | SEIs/SCEs influence referral to SCEs/SEIs | Wide influence | 4 | 4 |

| Reduced influence | 1 | 1 | ||

| Youth participation in the decision to transition | Broad participation | 13 | 14 | |

| Low participation | 5 | 5 | ||

| Family participation in the decision to transition | Broad participation | 7 | 7 | |

| Low participation | 5 | 5 | ||

| Social stratification in school progression (Solís and Blanco, 2014; Rujas, 2020) | Horizontal stratification | Unidirectional majority stratification: SEIs to SCEs | 14 | 14 |

| Vertical stratification | Opportunity to overcome stratification: transitions from SCEs to SEIs | 5 | 5 | |

| Organizational culture (Valdés and Pérez, 2021) | Culture of neoliberal rationality | Emphasis on academic and disciplinary dimensions. Institutional verticality. No/limited educational support. | 44 | 42 |

| Inclusive culture | Emphasis on the individual from a holistic perspective. Collaborative practices. Importance of welcome and support. | 79 | 77 |

Note: Compiled by the authors

The decision to move to SCEs before completing compulsory secondary education is led by secondary schools and the educational inspectorate, which adhere to educational regulations and horizontal verticality. Secondary school professionals assess the need for this transition following poor results of previous initiatives such as an "individualized plan" (E_SEI_OT4: 6), "educational reinforcement, curricular adaptations, repetitions (...)" (E_SEI_OT2: 3). They also use repressive measures: "there has to be some expulsion, some sanction..." (E_SEI_OT1: 4). When students do not respond, the institution considers a transition: "that´s when we begin to consider another type of education" (E_SEI_OT4: 6). These stories exemplify the neoliberal rationality of the formal system.

Guidance professionals at secondary schools contact SCEs and share the proposal with the students and their families, who then make the final decision, although the institution presents only one option. These proposals typically involve young people under age 16 who have not completed their compulsory schooling. Both institutions state the following:

(…) when a student here was not functioning and we did not know what to do with him, before he dropped out (…) he contacted [SCE name] through a psychopedagogue from the Guidance Department and, then, through inspection, the documentation is filled out and he is referred, well, we talk to the student and the family, they sign if they agree and he goes to the SCE (E_SEI_OT4: 4).

(…) almost everything comes through the guidance counsellors who usually stay at the centres. They usually come in groups, meaning the guidance counsellor with five kids from the centre (E_SCE_D6: 68).

Students also note the initiative and the power exercised over their own professional and life projects by the SEI as promoters of their departure and referral to SCEs. SEIs sometimes use this power in an imposing manner, which silences the students’ stories, ignores their right to choose and stigmatizes the SCEs by characterizing them as a punishment. The students highlight the SEIs’ emphasis on discipline and the lack of support:

I repeated a year in compulsory secondary school, then in my second year I had an accident and the headmistress grabbed me by the arm, firmly, took me to the office and sat me down and said: I´m going to send you somewhere [SCE], and she spoke to my parents. She explained it to me like hell... I was even furious" (GD_SCE_J2: 27).

At first, I was forced to join the cycle. (…) And I ended up liking it and now I work in that field (GD_SCE_J6: 177).

The training path for the transition to SCEs does not seem to be a major concern at the time of students’ exit. Little thought is given to what vocational training these students, who have been expelled from the formal system, wish to pursue:

We need help to clarify things (…) the orientation in SCEs is lacking, they don´t know what they want to do (E_SEI_OT9: 4).

I asked a boy: Why did you come here? He said: Well, because at school they told me to come to the mechanics school and because my mother did too (GD_SCE_E2: 54).

Families are also considered. High schools inform them about young people´s progress: "If they are not emancipated, we must inform them (...)" (E_SEI_OT2: 8). However, according to high schools, families are not always present or do not have the necessary resources to address problems of adaptation to the educational system. The schools sometimes demonstrate a classist view:

(…) there are no families behind it or not as any teacher with a need would expect, they pick up the phone and behind it there is a family with availability of schedules and resources… (E_SEI_OT6: 2).

In contrast, the SCEs rely more on the influence of families and bring them closer to the centre to make them participate: “The reception is done with the families, they are the ones who decide” (GD_SCE_E1: 83).

Young people seem to have less of a say in this selection process. When they do not participate in the process and are subjected to pressure from secondary schools and/or their own families, they can also drop out at the SCE level:

(…) there is usually some dropout (…) these are young people who come under great pressure, either from their family or from their teachers, and they don´t want to do anything (E_SCE_D32: 111).

The above situation is corrected with welcoming processes upon arrival at the SCEs, which include orientation sessions. SCEs are promoted as inclusive environments, where decisions, goals, and individual itineraries are agreed upon and young people are the protagonists in their life projects:

(…) individual objectives that are made in consensus with the student (GD_SCE_E1: 135).

In the end, the decisions are theirs, and many times, no matter how much you have told them, they decide other things (GD_SCE_E4: 433).

Some young people highlight their desire to work, a

Many kids want to work now. And you tell them, well, to work, you still have to prepare the way (GD_SCE_E1: 145).

SCEs become, in some cases, a

In other cases, the students’ choices reflect the degree to which their own preferences match the offers, subject to structural limitations: "In the Department of Education criteria, you can put several options for enrolment, but of course, you don´t always get in the first one, if there are no places..." (GD_SCE_E4: 50). Young people weigh different training courses that they do not always find desirable, together with SCE counsellors, and use "rational compensation" mechanisms for second or third options, where the young people´s desires are postponed.

I wanted to do aesthetics, but [SCE name] has x courses. It´s not that they have all the courses available, it´s that maybe there´s another course and they suggest to you: there´s this course and this one. So you don´t have to take this gap year... (GD_SCE_J6: 230).

The transition from SCEs to SEIs is residual. Professionals at some SEIs do not consider it viable for students to return from SCEs: "They´re doing very well there, and when they leave, they don´t really come back here because there are no opportunities...to do baccalaureate... Before that, they do a medium-level training cycle" (E_SEI_OT4: 5).

The referral from an SCE is directed to vocational training institutions to expand the young people’s professional skills and to adult education schools (EPAs) to consolidate basic skills: “We have those who go to intermediate-level cycles and those who do not manage to get in (…) go to finish secondary education at an EPA” (E_SCE_D32: 153).

There are still gaps in the transitions between re-entry into education and the labour market:

There are young people who complete their vocational training. They want to work no matter what, they work for a year, then realize they want something more and come to evening classes to prepare for the entrance exam or finish high school (E_SCE_D32: 65).

Decisions to transition between SEI and SCEs are made primarily by these institutions, limiting the choices of students and families to the reception process carried out by the SCEs. Transitions are not truly two-way, with moves from SEI to SCEs being more common. Some transitions to intermediate vocational training occur within SCEs themselves:

We have a basic and intermediate grade group from the same family. Twenty percent of the places in the intermediate grade are reserved for those coming from basic education. (GD_SCE_E4: 74).

(Dis)articulation of the transition

The articulation of the transition demonstrates levels of coordination and mutual understanding between SEI and SCEs. This allows us to analyse whether opportunities for collaboration exist to benefit the continued education and/or employment of the young people in the study (Table IV).

Table IV. (Dis)articulation of the transition

| Categories/Subcategories | Analysis | Research 1 | Research 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual institutional knowledge | Effort to spread one´s own role among institutions | 9 | 9 |

| No dissemination of one´s own role among institutions | 4 | 4 | |

| Articulation in transition from SEIs to SCEs | High | 32 | 31 |

| Null | 11 | 10 | |

| Articulation in transition from SCEs to SEIs | High | 12 | 12 |

| Null | 7 | 7 |

Note: Compiled by the authors

With respect to mutual knowledge, SEIs do not take actions to make themselves known to SCEs: “No, unless we have students in common or in referral processes, in which case there is coordination and relationship with those centres” (E_SEI_OT3: 2).

In contrast, SCEs value the fact that SEI are aware of them: "It´s extremely important to inform the institutes and their guidance counsellors about the existence of the SCEs so they know there are other options" (GD_SCE_E6: 151). SCE managers consider this proof of good coordination and consolidation among the organizations.

The institutes know us, right? And it´s a history of coordination and collaborative work (E_SCE_D13:16).

(…) we are a well-established entity. They know us where we are, in the neighbourhoods: social services, schools, etc. (E_SCE_D3: 118).

Coordinating the process is complex for children under age 16, who remain linked to both institutions: enrolment remains with SEIs, but training and assessment are carried out by SCEs:

(…) they are enrolled in their SEI and to the extent that the institute wants, they come to a social and employment centre, but their official enrolment remains at the institute because they are under 16 and we set the grades [SCE]. (GD_E20_E1: 174).

Articulation through meetings between institutions is considered common by the IES: “I do see many educators from [SCE name] who meet with the institute tutors” (E_IES_OT6: 4).

The SEIs acknowledge that the SCEs provide useful differential resources to prevent school dropout, “with lower ratios and much more personalized, and perhaps much more manipulative, everything. That´s where they respond” (E_SEI_OT4: 6). They value the follow-up provided by the SCEs and believe that young people do as well: “following up on how to ensure that the person who has returned to school is well supported (...). I think the children perceive that” (E_SEI_OT6: 5).

The initial reception at the SCE is a careful process: “the kids come to us, there is a selection, an orientation is done so that the kids and we see (…). It is the process” (GD_SCE_D2: 75).

In referrals from SCEs to SEI, mainly those for Vocational Training (VT), the SCE tutor contacts the SEI: “the experience with some SCEs is that it is usually the tutor who makes the contact” (E_SEI_OT2: 7). The SCE tutor “must send the VT advisor the report that allows access to the Basic Vocational Training (BVT), as regulated by legislation” (E_SEI_OT2: 6). However, “in access to the intermediate and advanced levels, the school of origin does not provide reports or documentation unless the VT advisor requests them” (E_SEI_OT2: 6).

The SCEs try to “return them to the educational system, so that they can resume their… [training]” (E_SCE_D7: 13); however, referrals to training do not always occur within the regulated educational system.

Referrals to secondary schools by SCEs are sometimes accompanied by requests for support to improve the students´ adaptation to the secondary school:

There are some who have graduated in the workshop classroom, spectacular processes, and you think they will be able to sustain a cycle. (…) Well, after 4 days, they [teachers from the institution] come asking for guidance, because they are not well (GD_SCE_E2: 119).

A paradox arises if SCEs’ referrals to institutions, usually vocational training institutions, are not taken care of: the risk of dropping out is transferred to higher education when a referral is made back to the formal education system, evidencing, in many cases, the maintenance of vertical stratification after passing through the secondary education.

Therefore, coordination is led by SEI when they aim to refer these young people. SCEs place greater emphasis on supporting young people during these processes and use coordination as an enabling element.

Effect of educational policies on transitions

Despite political ups and downs and successive educational reforms in Spain, the reforms’ implementation defines significant transition models and patterns of educational trajectories (Table V).

Table V. Effect of educational policies on transitions

| Categories/Subcategories | Analysis | Research 1 | Research 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion in the formal education system (Morentin and Ballesteros, 2024) | Students do not leave SEIs | 15 | 15 |

| Does not prevent students’ leaving SEIs | 6 | 6 | |

| Continuing at SEIs does not guarantee inclusion | 6 | 6 | |

| Patterns of educational trajectories (Walther et al., 2015) | Academic fluency | 0 | 0 |

| Academic discontinuity | 0 | 0 | |

| Smooth career paths | 0 | 0 | |

| Discontinuous career paths | 9 | 9 | |

| Remedial or intermediate trajectory | 13 | 13 | |

| Regional educational competence | Diverse solutions to inclusion | 10 | 11 |

Note: Compiled by the authors

Organic Law 3/2020 on Education and Organic Law 3/2022 on the organization and integration of vocational training emphasize inclusive education. The continued availability of the basic vocational training cycle in secondary schools, aimed at young people under 16 years of age who have difficulty following mainstream education, also consolidates a remedial career path:

(…) with 15 years old in the school year (…) they can enter the BVT, and this (…) has reduced the demand for schools... (E_SEI_OT8: 2).

Now, with just three failures, you can finish (…) The system, the schools, are taking on students who used to come to us. Yes, the BVT and accessibility to promotion (GD_SCE_E1: 211).

The evolution of the profiles of young people who transition to SCEs is subject to these regulations: "We currently don´t have anyone with a high school profile" (GD_SCE_E1: 206). SEIs are critical of the application of these regulations, considering that the problems are not resolved within the formal education system, which is incapable of offering anything more than remedial paths. Among those who value transitions to SCEs, a more appropriate response is as follows:

(…) they [the SCE] have been left with less support, a little lack of institutional support so that they can develop their activity as they did, and that, at the centre level, was very important, due to the level of maturity that the students bring (E_SEI_OT8: 8).

However, outsourcing and referral continue to occur in some autonomous communities that have not integrated the BVT under "shared schooling" formulas, which ultimately relegate students exclusively to SCEs: "Shared schooling, as such, does not exist. They don´t go to school some days and come here other days, but it is always here" (GD_SCE_E2: 23).

SCE educational teams consider the response regarding the VT offered by the institutions to be incomplete. It is practical and manipulative training but lacks a comprehensive approach:

(…) you can start to detect in the orientation some students who may need something more practical, and I think it is a very good option… But (…) there is also a part of demotivation or there is a process of integration into a society, that is, it is broader (GD_SCE_E2: 312).

There is also a high percentage of immigrants in some territories, reflected in the profile of SCE candidates: "There are constant arrivals of foreign-born people, newly arrived in Spain, with a lack of Spanish. In other words, are they an SCE participant? It´s textbook, but we need a base" (GD_SCE_E1: 65).

On the other hand, the assumption of educational responsibilities by regional governments has led to differentiated training offerings in each region´s SCE programs. Only a few regions, such as the Basque Country, offer a secondary education degree and/or a vocational training qualification (common in primary and secondary education and training and less common at the intermediate and advanced levels). Among the benefits of this regulated vocational training are reduced tensions in secondary schools and the guarantee of success due to accumulated expertise, with the regional government establishing admissions guidelines:

(…) you welcome them and inform them about the course, their current situation, where they come from, what qualifications they have or don’t have (…) who is admitted to each of the courses? … part of the Basque Government, the guidelines it sets, what order it will implement in admission (GD_SCE_E4: 14).

Discussion and Conclusions

The results challenge the dominant discourse that assumes homogeneity in the profiles of young people in SCEs (García Gracia & Sánchez Gelabert, 2020). Regarding the profiles of young people who transition between SEI and SCEs, different perceptions are observed. SEI professionals highlight the disengagement and poor performance of young people, in addition to the complex social context; SCE educators emphasize the opportunities for change and the strengths of young people and their families. The experience in SCEs also makes young people more aware of their transitions, reinforcing the idea of different perceptions between SEI teachers and students when interpreting the disruption in the classroom (Martínez Fernández et al., 2020).

With respect to the decision-making process regarding the transition,

neither young people nor their families have much agency. The scarcity

of economic, cultural, and social capital (Scandurra et al., 2020)

limits their participation in social life and the definition of their

life plans. Thus, "peripheralization" is reproduced (Naumann

& Fischer-Tahir, 2013), even with programs aimed at equal

opportunities. Some results show young people´s disaffection with SEI,

while their connection to SCEs and their educational continuity are

strengthened (Solís & Blanco, 2014). Preventive measures become

compensatory when they do not ensure permanence in the system. This work

helps show how, in many cases, young people are not the ones who make

the decision to transition to SCEs but rather accept their

"degradation" and end up believing it was their choice (Rujas,

2020). Formal guidance from secondary schools and the informal influence

of family or friends influence a process known as "cooling

off" (Walther et al., 2015), which hides the selective function of

the educational system, although superficially, it seems to offer them

"opportunities in life" (GD_SCE_E3: 81). In doing so, the

school system seems to treat them fairly, but the pattern that best

represents their transition to SCEs is

One limitation of this study is the time gap between the interviews (March–June 2021) and the focus groups (October 2023), although it did allow for the inclusion of questions about intermediate outcomes. Additionally, it would be useful to take a qualitative longitudinal approach in future research to explore the educational and employment trajectories of these young people after their time in SCEs.

Greater coordination between the formal and informal education systems on the basis of mutual understanding, coordination, and commitment is needed. If the formal system has structural limitations in serving certain groups, the more flexible and adaptive informal system must be strengthened to improve the transitions of groups experiencing disaffection into the education system. With these key elements in mind, support will be effective; in contrast, the different structures will only "allow the ´diversion´ of those who will inevitably drift" (Funes, 2009, p. 61).

Educational inclusion, championed by Lomloe (2020), seeks to resolve tensions between comprehensive education up to the age of 16 and the diversification of educational pathways at early ages. This debate must consider the relevance of the educational context. Nonformal contexts, such as SCE, offer solutions to young people excluded from the formal system. The dilemma of education within or outside the formal system raises questions about the effectiveness of high school education for students with negative school experiences who require more in-depth support and guidance.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Referencias bibliográficas

Asociación Española de E2O (2024).

Barr, N. (2020).

Collet, J., Naranjo, M., & Soldevila-Pérez, J. (2022).

Cuconato, M., & Walther, A. (2015). ‘Doing transitions’ in

education.

Dupéré, V., Leventhal, T., Dion, E., Crosnoe, R., Archambault, I.,

& Janosz, M. (2015). Stressors and turning points in high school and

dropout: A stress process, life course framework.

European Commission, EACEA and Eurydice/Cedefop (2014).

Flick, U. (2004).

Funes, J. (2009).

Guba, E. G. (1983). Criterios de credibilidad en la investigación

naturalista. En J. Gimeno Sacristán, & A. Pérez Gómez (Comps.),

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln Y. S. (1998). Competing Paradigms in

Qualitative Research. En N.K. Denzim , & Y. S. Lincoln,

INE (2024).

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer

agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la

Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. BOE núm. 340, de 30 de

diciembre de 2020, 122868 -122953.

Ley Orgánica 3/2022, de 31 de marzo, de ordenación e integración de

la Formación Profesional. BOE núm. 78, de 1 de abril de 2022,

43546-43625.

Martínez Fernández, M.B., Chacón, J.C., Díaz-Aguado, M.J., Martín,

J., & Martínez Arias, R. (2020). La disrupción en las aulas de ESO:

un análisis multi-informante de la percepción de profesores y alumnos.

Morel, N., Palier, B., & Palme, J. (Eds.).

(2013).

Morentin, J., & Ballesteros, B. (2024). Educar reconociendo al

estudiante. Narrativas desde el desenganche educativo.

Naumann, M., & Fischer-Tahir, A. (Eds.). (2013).

Nes, K., Demo, H., & Ianes, D. (2017). Inclusion at risk? Push-

and pull-out phenomena in inclusive school systems: the Italian and

Norwegian experiences.

NESSE (2009).

Perelló, S. (2009).

Rawolle, S., & Lingard, B. (2008). The sociology of Pierre

Bourdieu and researching education policy.

Rujas, J. (2020). Cómo se calma al primo en la ESO: la

externalización a PCPI y la subjetivación de la selección

escolar.

Samuel, R., & Burger, K. (2020). Negative life events,

self-efficacy, and social support: Risk and protective factors for

school dropout intentions and dropout.

Scandurra, R., Hermannsson, K., & Cefalo, R. (2020). Assessing

young adults’ living conditions across Europe using harmonised

quantitative indicators: Opportunities and risks for policy makers. In

M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.),

Solís, P., & Blanco, E. (2014). Desigualdad social y efectos

institucionales en las transiciones educativas. En E. Blanco, P. Solís y

H. Robles (Eds.),

Sosa-Sánchez, I.A. (2021). Cuerpo, self y sociedad: una reflexión

desde la fenomenología y el interaccionismo simbólico.

Tarabini, A. (2016). La exclusión desde dentro: o la persistencia de

los factores push en la explicación del Abandono Escolar Prematuro.

Organización y Gestión Educativa.

Valdés, R., & Pérez, N. (2021). Celebrar la diversidad y defender

la inclusión: la importancia de una cultura inclusiva.

Walther, A., Warth, A., Ule, M., & du Bois-Reymond, M. (2015).

‘Me, my education and I’: constellations of decision-making in young

people’s educational trajectories.

Información de contacto / Contact info: María José Chisvert Tarazona. Universidad de Valencia, Facultad de Filosofía y Ciencias de la Educación, Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar. E-mail: maria.jose.chisvert@uv.es

García Gracia, M., & Sánchez Gelabert, A. (2020). La heterogeneidad del abandono educativo en las transiciones posobligatorias: Itinerarios y subjetividad de la experiencia escolar. Papers, 105(2), 0235-257. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers.2775

Marhuenda-Fluixá, F., & Chisvert-Tarazona, Mª. J. (2022). Resultados del modelo de las escuelas de segunda oportunidad (E2O) acreditadas en España en respuesta al abandono escolar temprano y al desempleo juvenil. Asociación Española de E2O. https://www.e2oespana.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Informe_Resultados_Modelo_E2O.pdf