What happened with PISA 2018 in Spain? An explanation based on response times to items

¿Qué pasó en España con PISA 2018? Una explicación a partir de los tiempos de respuesta a los ítems

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-411-727

José G. Clavel

Universidad de Murcia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5800-319X

Francisco Javier García-Crespo

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1050-462Y

Luis Sanz San Miguel

Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (INEE)

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1050-462X

Abstract

In December 2019 OECD decided not to publish Spanish results on

Reading for PISA 2018. Apparently, they had found

Keywords:

PISA 2018, Reading fluency, rapid guessing, process data, odd behaviour, loglinear model, Reading performance

Resumen

En diciembre de 2019, la OCDE decidió no publicar los resultados de la competencia en lectura para España de PISA 2018 porque, aunque no se habían detectado errores en la realización de la prueba, los datos mostraban lo que llamaron una respuesta poco plausible de un porcentaje elevado de estudiantes, lo que no permitía asegurar la comparabilidad internacional de los datos españoles. Meses después, en julio de 2020, se publicaron finalmente los datos, acompañados de un estudio independiente que señalaba varias posibles explicaciones de esos resultados inesperados. Entre esos motivos se citaba la fecha de realización de la prueba, y se añadía que quizás también tuvo su influencia la estructura de la prueba.

En este trabajo mostraremos que es precisamente la estructura de la

prueba, lo que causó el problema. En concreto, la presencia de los

llamados “

A partir de la estructura de la prueba, y los tiempos de respuesta de los alumnos a cada uno de los ítems, determinamos aquellos estudiantes que tuvieron comportamientos anómalos y qué características tienen. Además, estudiamos qué efecto han provocado en los rendimientos medios de sus CCAA y cuál hubiera sido su efecto con una estructura distinta de la prueba.

Palabras clave:

PISA 2018, fluidez lectora, rapid guessing, process data, comportamientos anómalos, modelo loglinear, rendimiento en lecturaIntroduction

On November 19, 2019, the OECD issued an official announcement stating that Spain’s Reading results would not be released together with those of the other countries on December 3, 2019. The announcement said:

“

Months later, on July 23, 2020, Spain’s reading results were published, along with a brief independent study (Annex A9) that offered possible explanations for the detected anomalies. The study pointed out, among other factors, that the timing of when the PISA test was conducted in Spain could have influenced the results. In the same document, it was also noted that the impact of one section of the test, Reading Fluency, might have been more significant than initially expected:

“

Apparently, the anomalous behaviour of some students in the Reading Fluency items (hereinafter RF) triggered the unexpected results in some Autonomous Communities, leading to not publishing Spain´s PISA 2018 reading results in December 2019. But... What characteristics do the students who exhibited this anomalous behaviour have? Why did this problem occur in some Autonomous Communities and not in others? What could have caused this behaviour? We will attempt to answer these questions in the following study using the published PISA 2018 reading results.

Our work falls within the category of those who analyse the data available since the tests are conducted on a tablet, as in the case of PISA 2018 (Goldhammer et al. 2020). Indeed, computer-based assessments have had several methodological consequences. Among other things, it has made it possible to design adaptive tests that change according to students´ responses (as is the case with PISA tests); it has made it possible to design response items that were not technically possible before; and, above all, it has allowed to polish test evaluation by incorporating all the collateral information available into the model (see, for example, Bezirhan et al., 2020). Our work falls within this third area: we use the computer trace (log-files) generated by the student as they progress through the test (process data) and combine it with their answers (response data). For a review of how the two sources of information are being integrated into LSAs such as PISA, see Anghel et al (2024).

According to the test, these log files may include information such as which keys were pressed or how the cursor moved across the screen, and in more advanced assessments, even data on eye movements or heart rate for each item and each participant. In PISA 2018, the log files collected response times: excessively short times would be a sign of rapid guessing behaviour when answering (Wise, 2017). This would reveal the test-taker disengagement (Avvisati et al, 2024), which is a risk in tests such as PISA, where students have nothing at stake (what the literature refers to as a low-stakes context).

A second source of information available in PISA 2018 is non-response to certain items. As pointed out by Weeks et al. (2016), a student´s failure to answer does not necessarily mean that they do not know the answer. They may not have answered it due to lack of time, or they may simply not have put enough effort. This would therefore be another aspect of test-taker disengagement. However, what happened in Spain with PISA 2018 is related to the RFs, and these were answered by all participants, therefore we will leave this aspect of the logfiles for further research.

Following the introduction, we will provide a detailed description of the test structure, which is a key aspect of our work on RF. The methodology section presents the variables selected for the study, a descriptive analysis of anomalous behaviours across the Autonomous Communities, and the multilevel log-linear model used to explain the causes of these anomalies. The subsequent section discusses the estimation results and offers a prediction of what might have occurred if RF had been weighted differently. Finally, the paper concludes with recommendations aimed at preventing a recurrence of the issues observed in Spain with PISA 2018.

Test Structure: Multi-Stage Adaptive Design

The fact that the PISA assessment can be taken on a computer makes it possible to use a MultiStage Adaptive Testing design (MSAT), which presents new items to students based on the skills they have demonstrated so far. This enables to determine more accurately what students can do with what they know at different skill levels, obtaining a more sensitive test, especially at the lower levels of PISA performance.

The MSAT design for PISA 2018 consisted of three stages: core, stage1, and stage2. In each stage included a number of units (5 in the core, 24 in stage1, and 16 in stage2), with each unit containing several items. On the device used to take the test, students saw only a selection of these units. Specifically, out of a total of 45 units and 245 items available, each student completed 7 units, for a total of between 33 and 40 items, depending on the level of skill they demonstrated. A detailed explanation can be found in Chapter 2 of the test´s technical report (OECD, 2018 https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/pisa2018technicalreport/).

In addition to these three stages, PISA2018 included a preliminary stage to measure students´ RF. In this stage, student read a short expression and indicated whether it was logical or not. The items were simple sentences in which students only had to decide whether the sentence made sense. For example, “The window sang the song loudly” would be illogical, while “The man drove the car to the warehouse” would make sense. Both examples are taken from the PISA 2018 test.

In summary, students began the test with very simple RF items, followed by a random core stage and two subsequent stages (stage1 and stage2) determined by their performance. From the core stage onward, item assignment was based on the students´ results on the automatically scored items. According to Item Response Theory (IRT), the estimated performance function for each student depends not only on whether they answered correctly, but also on the difficulty of the questions they answered correctly. Therefore, a good student who only receives simple questions and answers them correctly will have a lower estimated ability than a good student who answers more difficult questions correctly.

Measuring Reading Fluency

As noted earlier, students’ RF was assessed in a preliminary stage. However, the results of this stage did not determine which items were included in each student’s testlet. Regarding its role in performance measurement, the OECD decided not to incorporate RF results into the different subscales of reading (locating information, understanding, evaluating, and reflecting), but instead to include them in the overall competency score. To date, we have not found any OECD publication explaining precisely how RF was incorporated. Nevertheless, the OECD provides, upon request, alternative plausible values for each student that exclude RF results.

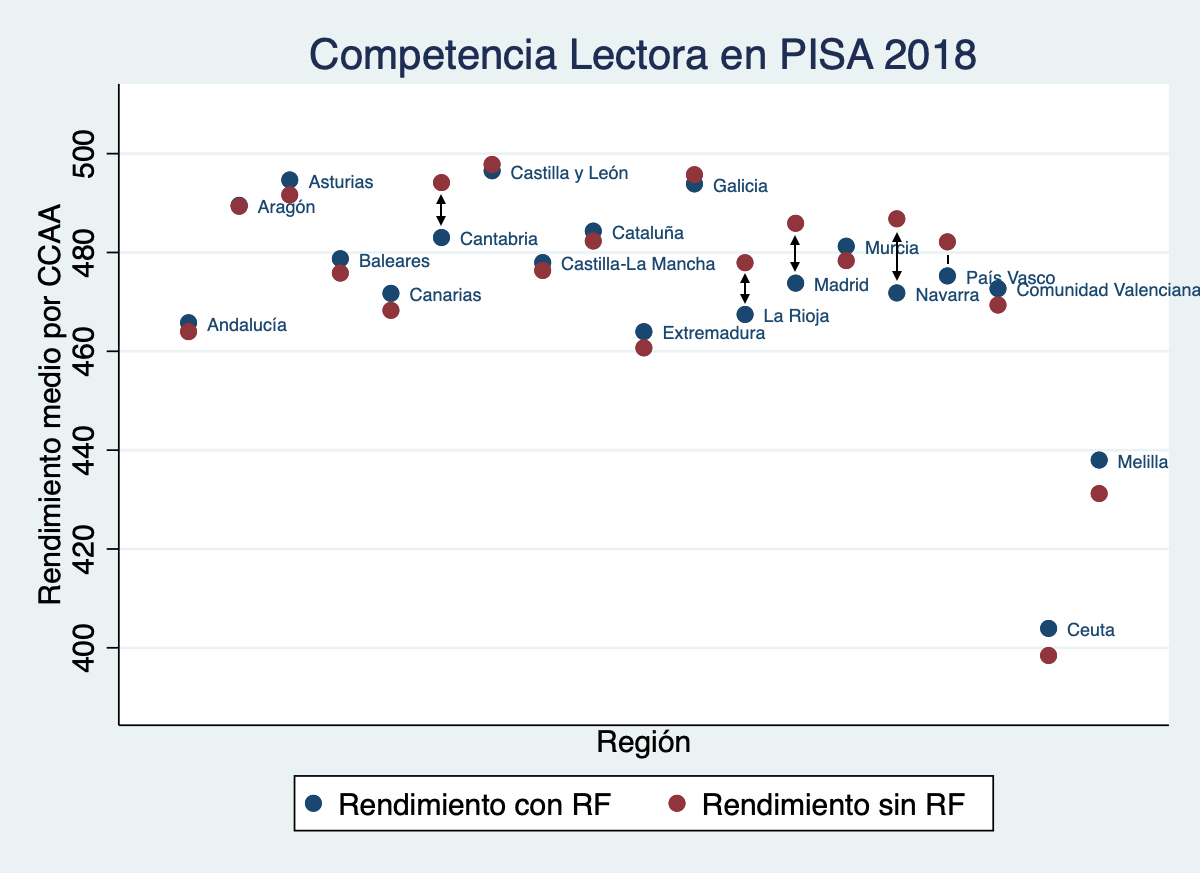

Using these alternative data, we calculated the average performance by region and compared it with the published results that included RF. As shown in Figure 1, the effect of RF is particularly significant in the Autonomous Communities of Cantabria, Madrid, Navarre, La Rioja, and the Basque Country, where the impact diverges from the pattern observed in other regions, whose results are more consistent with each other.

Figure 1

The PISA 2018 database provides extensive information for each item measuring RF. Most students had to answer 22 items, and for each we have data on their response, the time taken to answer, and whether the response was correct. On average, Spanish students answered 19.33 items correctly, with a median of 20, which was expected given the simplicity of the task.

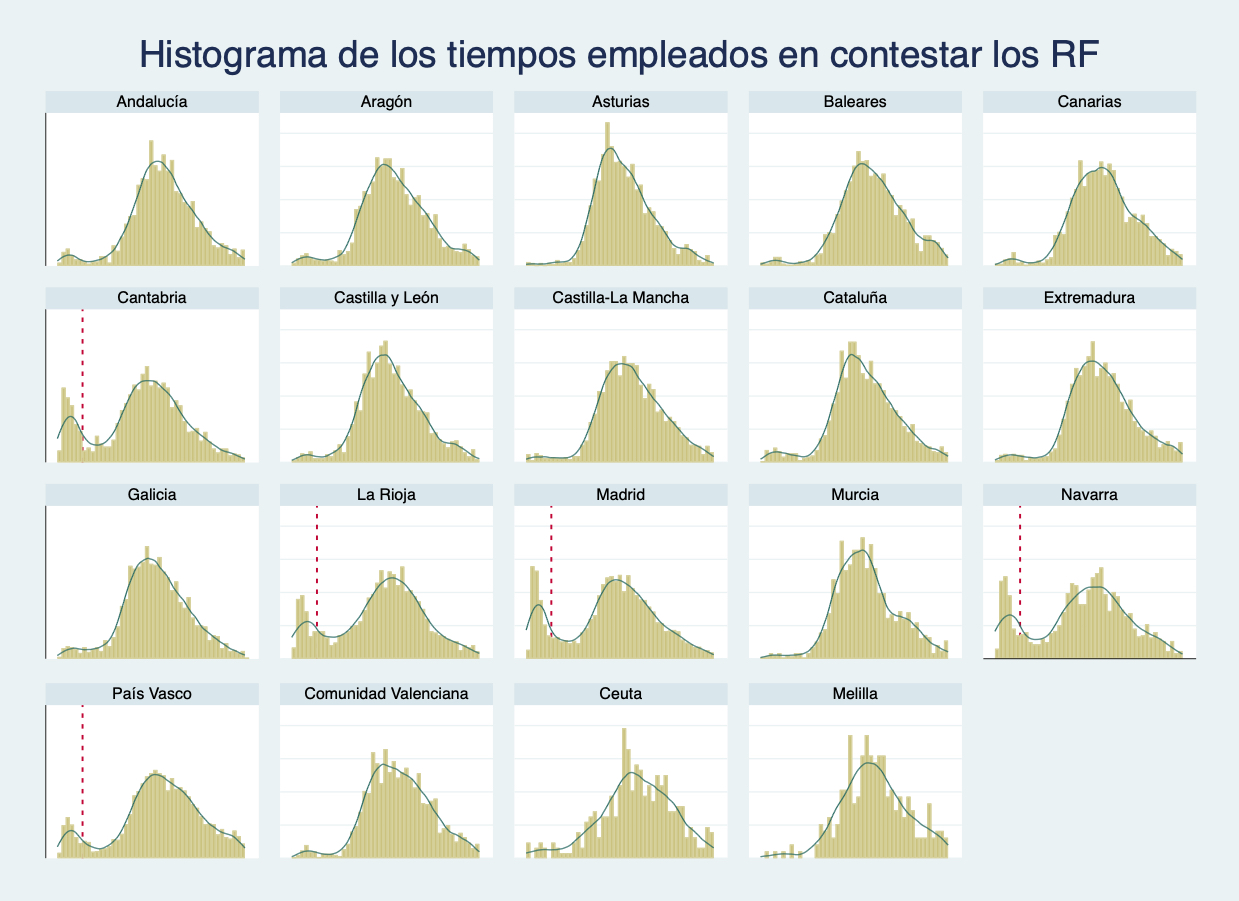

However, an extraordinary finding emerged when analysing response times, that is, the total time each student spent answering the 22 questions. A significant proportion of students (up to 15% in some Autonomous Communities) completed all 22 items in under 22 seconds, which is far too little time. This was possible because the items were displayed consecutively on the device, and the answers (“yes” or “no”) always appeared in the same position on the screen. As a result, students could simply tap repeatedly on the same box to finish this section in under 22 seconds, typically getting about half of the answers correct. Figure 2 highlights these anomalous response-time patterns in the Autonomous Communities of Madrid, Cantabria, Navarre, La Rioja, and the Basque Country.

Figure 2

Distribution of time spent answering the 22 RF questions in different regions.

Note: The dashed red line reads 22 seconds

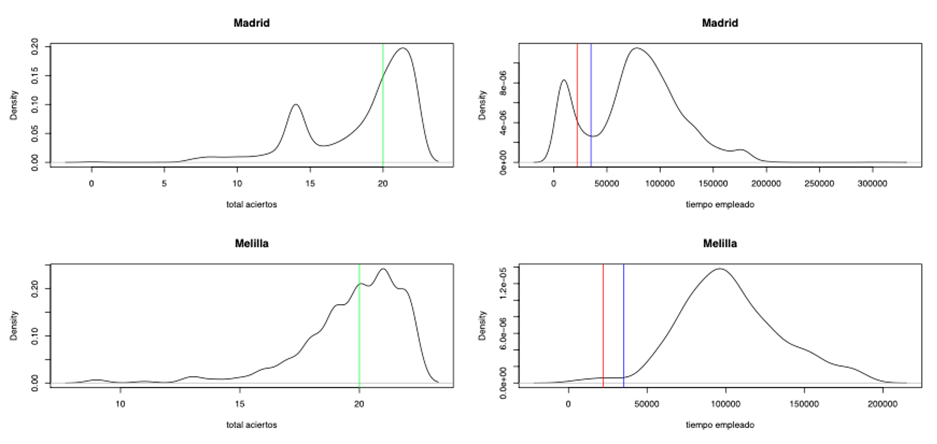

This response-time pattern provided a clue as to what might have happened. We confirmed that the distribution of correct answers on the RF items was also affected by the same anomaly, as shown in Figure 3, which illustrates the distributions for Madrid and Melilla. It was therefore evident that a group of students (significant in some Autonomous Communities) had answered the RF questions “carelessly.” The next step was to identify the characteristics of these students and, most importantly, to assess whether their behaviour had any impact on the overall reading results of the test.

Figure 3

Distribution of the number of correct answers (left) and response times (right) to the RF questions for Madrid and Melilla in PISA 2018.

Methodology

Our first task was to define what we considered anomalous behaviour. To do so, we analysed the response times for the RF items in relation to students’ overall test performance. We then examined how these students were distributed across Autonomous Communities and what their main characteristics were. Finally, using a logit model, we investigated what factors might have triggered such anomalous behaviour.

Dependent Variable: Anomalous Behaviour

We defined anomalous behaviour as a situation where a student

performs poorly on the RF stage but achieves strong results in the rest

of the test. This required specifying what we mean by “performing

poorly” in the preliminary stage and “performing well” in the main test.

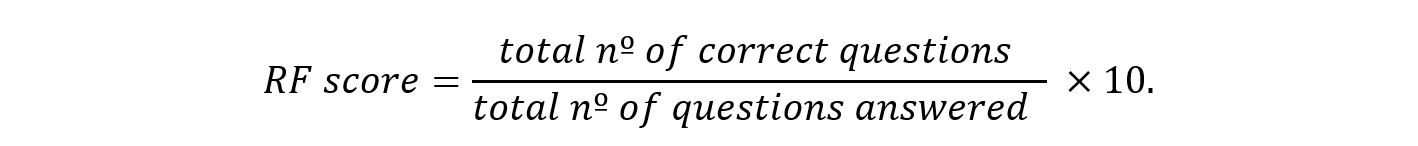

For the first part, we calculated the variable

In this study, we classified a student as having performed poorly in the preliminary stage if they obtained a score of fewer than 8 correct answers out of 10 in RF. Table 1 shows the regional distribution (weighted and unweighted) of students who scored below 8 in RF. Approximately 28% of these students were enrolled in schools in the Community of Madrid, 18% in Andalusia, and 11% in Catalonia. The Basque Country and the Valencian Community each accounted for around 6–7%, while the percentages for the remaining regions were below 5%.

Table 1

| Region | Number of students | Population represented | Percentage of the total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 202 | 10528 | 17.66% |

| Aragon | 189 | 1189 | 1.99% |

| Asturias | 117 | 439 | 0.74% |

| Balearic Islands | 140 | 806 | 1.35% |

| Canary Islands | 155 | 1763 | 2.96% |

| Cantabria | 491 | 1209 | 2.03% |

| Castile and Leon | 197 | 2128 | 3.57% |

| Castile-La Mancha | 177 | 1881 | 3.15% |

| Catalonia | 168 | 6614 | 11.09% |

| Extremadura | 174 | 1007 | 1.69% |

| Galicia | 272 | 2874 | 4.82% |

| La Rioja | 429 | 782 | 1.31% |

| Madrid | 1431 | 16883 | 28.32% |

| Murcia | 142 | 1427 | 2.39% |

| Navarre | 511 | 1911 | 3.20% |

| Basque Country | 740 | 3873 | 6.50% |

| Valencia | 150 | 4061 | 6.81% |

| Ceuta | 63 | 177 | 0.30% |

| Melilla | 22 | 75 | 0.13% |

| TOTAL | 5770 | 59625 | 100% |

A score below 8 on the RF items could also reflect reading

difficulties. Therefore, the criterion for identifying anomalous

behaviour combines performance on the RF items with behaviour in the

next phase of the test, the core stage. Specifically, we distinguish

between students who performed poorly on RF and were then

Table 2 presents, by Autonomous Community, the percentage of students who, despite scoring below 8 on RF, went on to achieve a high level of performance in the core section. The regions with the highest proportions of such students—between 20% and 30%—are Galicia, the Basque Country, Castile and León, La Rioja, Navarre, Madrid, and Cantabria.

Table 2

| Region | Percentage | pct_se |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 12,10 | 2,374 |

| Aragon | 10,51 | 2,332 |

| Asturias | 11,92 | 3,878 |

| Balearic Islands | 9,83 | 2,713 |

| Canary Islands | 9,34 | 2,441 |

| Cantabria | 29,20 | 2,767 |

| Castile and Leon | 19,65 | 2,706 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 11,32 | 2,745 |

| Catalonia | 10,57 | 2,492 |

| Extremadura | 9,89 | 2,099 |

| Galicia | 18,56 | 2,285 |

| La Rioja | 23,62 | 2,041 |

| Madrid | 24,04 | 1,538 |

| Murcia | 8,85 | 1,941 |

| Navarre | 23,96 | 2,321 |

| Basque Country | 19,43 | 2,553 |

| Valencia | 8,35 | 1,707 |

| Ceuta | 3,04 | 1,860 |

| Melilla | 0,00 | 0,000 |

Independent Variables

To better characterize students with anomalous behaviour, we selected several independent variables at both the student and school levels. These variables are grouped according to their type: categorical variables are presented in Table 3, and continuous variables in Table 4. The study population includes all students who scored below 8 on RF, regardless of their subsequent performance. For categorical variables, we report the percentage of students in each category; for continuous variables, we provide the mean, standard deviation, and their respective standard errors. It should be noted that continuous variables were standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one for the full sample of students assessed in PISA 2018.

Table 3

Analysis of Categorical Variables

| Score below 8 in RF and low or medium levels in CORE | Score below 8 in RF and high level in CORE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | % | %_se | % | %_se |

| CENTER OWNERSHIP | Public (71,84%) | 85,74 | 0,873 | 14,26 | 0,873 |

| Private (28,16%) | 76,99 | 2,049 | 23,01 | 2,049 | |

| EXT_JUN | Does not move up the extraordinary exam to June (58,65%) | 88,19 | 0,955 | 11,81 | 0,955 |

| Does move up the extraordinary exam to June (41,35%) | 76,45 | 1,105 | 23,55 | 1,105 | |

| SEX | Girl (39,51%) | 78,19 | 1,330 | 21,81 | 1,330 |

| Boy (60,49%) | 86,70 | 0,776 | 13,30 | 0,776 | |

| IMMIGRANT | Native (83,52%) | 81,11 | 0,972 | 18,89 | 0,972 |

| 1st or 2nd generation (16,48%) | 90,81 | 1,235 | 9,19 | 1,235 | |

| YEAR REPETITION | Does not have to repeat the year (58,43%) | 73,89 | 1,213 | 26,11 | 1,213 |

| Does have to repeat the year (41,57%) | 96,17 | 0,466 | 3,83 | 0,466 | |

Note: Estimated percentage of students in each category, together with the standard error of the estimate among students who scored below 8 out of 10 on the RF.

As shown in Table 3, among students scoring below 8 on RF, 71.84% were enrolled in public schools. Of these, 14.3% reached a high-performance level in the core section, compared with 23.0% among students in private schools. Additionally, 41.4% of students with an RF score below 8 attended schools that brought forward the extraordinary assessment to June. Of these, 23.6% achieved a high level in the core, compared with roughly half that proportion in schools that did not advance the assessment.

Gender differences also emerged: 39.51% of the students scoring below 8 on RF were girls, of whom 21.8% reached a high level in the core. By contrast, only 13.3% of boys achieved this level. Regarding immigration background, 16.5% of students with low RF scores were first- or second-generation immigrants, and of these, 9.2% reached a high level in the core—more than twice the percentage of native students (19%) (Table 3).

Year repetition was another key factor: 41.6% of students with RF scores below 8 had repeated at least one school year, and of these, only 3.8% achieved high performance in the core, compared with 26.1% among students who had not repeated (Table 3). In summary, more than 7 out of 10 students with RF scores below 8 attended public schools, around 60% were boys, and the vast majority were native students (83.5%). Notably, 6 out of 10 of these students were enrolled in schools located in Autonomous Communities that brought forward the extraordinary exams, usually held in September, to June of the 2017–18 academic year.

Table 4 shows the basic statistics for students with an RF score

below 8 for the continuous variables included in the model. Two of these

variables are school-related:

Table 4

| Variable | Description | Median | sd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Week in which the tests were conducted | 0,2415 | 0,98692 |

| COLT | Teacher involvement in the reading assessment | -0,1380 | 0,59551 |

| EFFORT | How much effort did you put into this test? | 0,0184 | 1,02565 |

| ESCS | Economic, social and cultural status index | -0,2819 | 1,08597 |

| DISCLIMA | Disciplinary environment in Spanish classes | -0,3598 | 1,09171 |

| TEACHSUP | Teacher support in Spanish classes | 0,0165 | 1,03440 |

| SCREADCOMP | Reading self-concept: perception of competence | -0,3240 | 1,02507 |

| SCREADDIFF | Reading self-concept: perception of difficulty | 0,0865 | 1,00486 |

| EUDMO | Eudaemonia: the meaning of life | 0,1683 | 1,01676 |

| GCSELFEFF | Self-efficiency in global matters | -0,1050 | 1,07948 |

| DISCRIM | Discriminatory school environment | 0,1660 | 1,13819 |

| BEINGBULLIED | Cases of bullying | -0,1602 | 1,64272 |

| HOMESCH | Use of ICT outside school (for school activities) | 0,1134 | 1,12059 |

| SOIAICT | ICT as a topic of social interaction | 0,1854 | 1,11804 |

| ICTCLASS | Use of subject-related ICT during lessons | -0,0992 | 1,01290 |

| INFOJOB1 | Information about the job market provided by the school | -0,0979 | 1,00313 |

Note: Mean and estimated standard deviation of estimates among students who scored below 8 out of 10 on the RF.

The

In the target group of students, variables such as test effort

(

For students who answered fewer than 8 items correctly in the Reading

Fluency (RF) section, scored significantly above the average in areas

such as sense of life purpose (

Log-linear models

We conclude the methodological section by presenting the model we have used to characterize students with “anomalous” behaviour in the test. In fact, given the hierarchical structure of the data and the nature of the dependent variable, the most appropriate approach is a multilevel log-linear model. As in other PISA cycles, the selection of students followed a classic two-stage cluster sampling procedure (school-student). Specifically, we applied the two-stage stratified sequential cluster model (OECD, 2017). First, strata were defined to best represent the target population of each study (in Spain, by Autonomous Community and school ownership). Within each stratum, schools were then selected sequentially and in proportion to their size, measured by the number of eligible students enrolled. Thus, larger schools had a higher probability of selection than smaller ones. In the second sampling stage, 42 students who turned 16 during the test year were selected, regardless of the class or grade in which they were enrolled. If a selected school had 42 or fewer target students, all of them took the test.

As we have already mentioned, the multilevel logistic regression model is the most suitable for this study (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2013; Gelman & Hill, 2006; Merino Noé, 2017; Snijders & Bosker, 2012). This method effectively accounts for variability in large-scale international educational assessments (De la Cruz, 2008; Iñiguez-Berrozpe & Marcaletti, 2018) while avoiding the use of replicated weights present in the databases (Fishbein, Foy, & Yin, 2021).

Therefore, to analyse the effect of predictor variables on the likelihood of anomalous behaviour, we employed multilevel logistic models with fixed effects that reflect the nested structure of the sample. Model estimation was carried out using HLM6© software, applying the Laplace approximation for Bernoulli models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), which enables analyses with binary dependent variables across hierarchical levels.

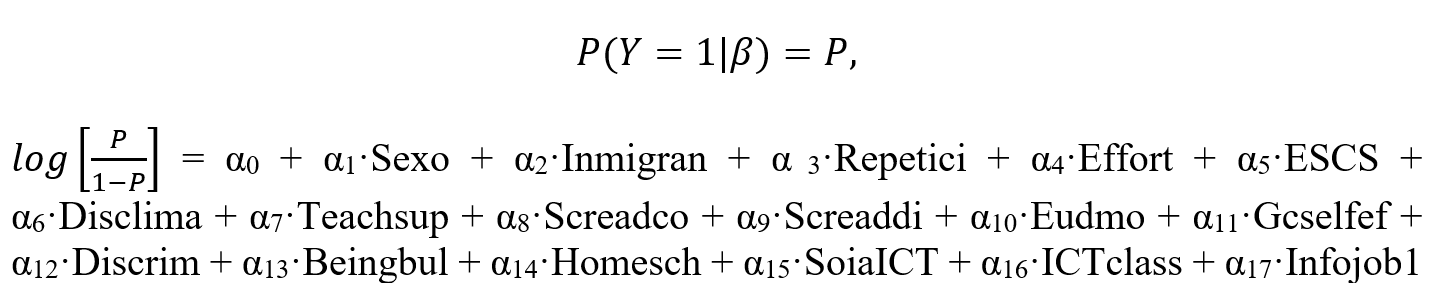

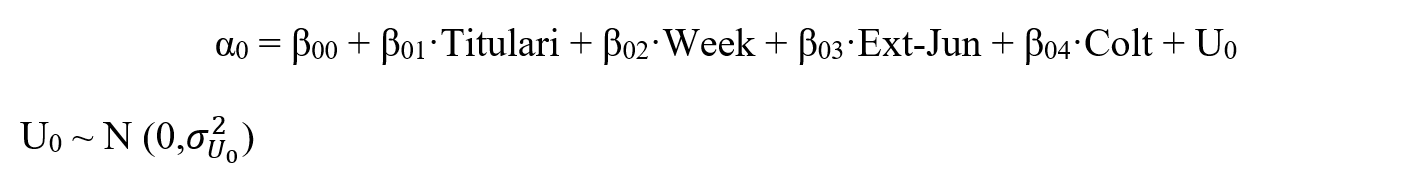

The equations of the model used are:

Level 1 of the model:

Nivel 2 of the model:

Where,

Y represents whether students exhibit anomalous behaviour or not.

αi are the fixed coefficients for each predictor variable at level 1.

β0i are the fixed coefficients for each predictor variable at level 2.

β00 is the regression intercept.

The variables are already presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Results

Table 5 presents the results of the hierarchical log-linear model, in

which the dependent variable was the condition “anomalous behaviour.”

The model is constructed on two levels: school level and student level.

Statistically significant variables were observed at both levels. At the

school level, it is worth noting that neither school ownership

(

At the student level, the adjusted multilevel model examined how and

to what extent these school variables influenced individual behaviour.

Neither gender (

Interestingly, students more likely to graduate from 4th year of ESO

were more prone to anomalous behaviour, probably due to their lack of

interest in the PISA test, which interfered with their main academic

focus. Similarly, students with a high self-concept in reading

competence (

Conversely, certain variables reduced the likelihood of anomalous

classification. These include perception of difficulty in reading

competence (

Table 5

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | Standard Error | T-ratio | P-value | Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRCPT2 | -1,343 | 0,111 | -12,137 | 0,000 | 0,261 | (0,210,0,324) |

| TITULARI | -0,053 | 0,097 | -0,549 | 0,583 | 0,948 | (0,784,1,147) |

| WEEK | 0,099 | 0,043 | 2,308 | 0,021 | 1,104 | (1,015,1,201) |

| EXT_JUN | 0,628 | 0,103 | 6,088 | 0,000 | 1,873 | (1,531,2,293) |

| COLT_MEA | 0,059 | 0,085 | 0,702 | 0,483 | 1,061 | (0,899,1,253) |

| SEXO | 0,106 | 0,084 | 1,263 | 0,207 | 1,112 | (0,943,1,312) |

| INMIGRAN | -0,358 | 0,140 | -2,557 | 0,011 | 0,699 | (0,532,0,920) |

| REPETICI | -1,666 | 0,129 | -12,945 | 0,000 | 0,189 | (0,147,0,243) |

| EFFORT | 0,175 | 0,040 | 4,375 | 0,000 | 1,191 | (1,102,1,289) |

| ESCS | 0,164 | 0,050 | 3,303 | 0,001 | 1,178 | (1,069,1,298) |

| DISCLIMA | 0,154 | 0,041 | 3,786 | 0,000 | 1,166 | (1,077,1,263) |

| TEACHSUP | 0,066 | 0,041 | 1,634 | 0,102 | 1,068 | (0,987,1,157) |

| SCREADCO | 0,324 | 0,046 | 7,116 | 0,000 | 1,383 | (1,265,1,512) |

| SCREADDI | -0,137 | 0,043 | -3,178 | 0,002 | 0,872 | (0,801,0,949) |

| EUDMO | -0,174 | 0,044 | -3,917 | 0,000 | 0,841 | (0,771,0,917) |

| GCSELFEF | 0,183 | 0,043 | 4,225 | 0,000 | 1,200 | (1,103,1,307) |

| DISCRIM | -0,282 | 0,044 | -6,365 | 0,000 | 0,754 | (0,691,0,822) |

| BEINGBUL | -0,081 | 0,034 | -2,369 | 0,018 | 0,922 | (0,862,0,986) |

| HOMESCH | -0,155 | 0,041 | -3,804 | 0,000 | 0,856 | (0,790,0,927) |

| SOIAICT | -0,096 | 0,046 | -2,087 | 0,037 | 0,909 | (0,831,0,994) |

| ICTCLASS | 0,115 | 0,039 | 2,967 | 0,003 | 1,122 | (1,040,1,211) |

| INFOJOB1 | -0,113 | 0,045 | -2,488 | 0,013 | 0,894 | (0,818,0,976) |

Conclusions

The exclusion of Spain’s results from the PISA 2018 reading assessment in December 2019 was a carefully considered decision by the OECD, following the observation of unexpectedly low performance in certain Autonomous Communities. Although not all of the decline in reading performance can be attributed to the nature and structure of the test, this study has shown that these factors did play a significant role in some cases.

A key element was the presence of an initial section, the Reading Fluency (RF) module, which some students appeared to treat “as if it did not count toward the final score.” This negatively affected the average performance of certain autonomous communities, since the adaptive multistage design of the test, combined with the use of Item Response Theory to calculate individual performance, prevented high-performing students from compensating for a poor start.

The proportion of students who responded “lightly” to RF items—evidenced by abnormally short response times—did not exceed 5% in most regions. However, the percentages were slightly higher in the Basque Country and the Valencian Community (around 7%) and markedly higher in three regions: Catalonia (11.09%), Andalusia (17.7%), and the Community of Madrid (28.32%).

We define students who performed poorly on the RF section but

excelled in the subsequent

In other words, high-achieving students who engaged in anomalous behaviour during the PISA 2018 reading test often responded randomly to the RF section—as indicated by their response times—for a variety of possible reasons: they may have been told the section did not count, they may have assumed the items were calibration exercises for the tablet, or they may have dismissed the section as “too easy” to be relevant. Due to the test’s design, however, they were then unable to recover their expected performance levels.

The OECD has already announced its intention to review both the administration of PISA and the impact of the RF modules on student performance. Nevertheless, definitive conclusions will not be possible until reading once again becomes the primary domain assessed. In the meantime, it would be valuable to investigate whether similar patterns of anomalous behaviour occurred in other countries, and to identify the characteristics of the students involved. It would be unrealistic to assume that this phenomenon was unique to Spain.

Given the importance of large-scale international assessments such as PISA—both in shaping public opinion and in guiding potential improvements to educational programs—we consider it essential to highlight the main factors associated with the anomalous behaviour observed among a significant share of students. Accordingly, we recommend:

- Modifying the structure of the test so that it includes RF items but minimizes the possibility of automatic responses. For instance, varying the position of answer choices across items.

- Scheduling the test earlier in the school year, sufficiently far from final exams, to ensure students are not distracted by end-of-year concerns.

- Conducting awareness campaigns to emphasize the importance of the test, underscoring its relevance both nationally (regional comparisons) and internationally (comparisons across countries).

Annex

To assess the impact that this behaviour had on the student´s final average performance, we used data provided by the OECD itself, upon request, on reading performance without taking into account the RF component. In other words, after requesting it from the OECD, we have an alternative score, specifically ten plausible alternative values, to measure the average effect of the RF.

Table AI shows the average value for each region including the RF component (i.e., the values already published by the OECD in its report of July 23, 2020), the average value of performance without considering the RF component, and the difference between the two results.

TABLE AI. Average returns by region, with and without RF, and sample sizes. Differences in average returns presented in Graph I.

| Region | Variable | Coefficient | Std_err | z | P_value | CI_low | CI_high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | pv_read_mean | 465.7783 | 5.321941 | 87.52 | 0.000 | 455.3475 | 476.2091 |

| Andalucía | pv_read_N | 1766 | |||||

| Andalucía | pv_readalt_mean | 463.9828 | 5.250794 | 88.36 | 0.000 | 453.6914 | 474.2741 |

| Andalucía | pv_readalt_N | 1766 | |||||

| Andalucía | difere | -1.795492 | .7040459 | -2.55 | 0.011 | -3.175397 | -.4155875 |

| Aragón | pv_read_mean | 489.5368 | 4.594978 | 106.54 | 0.000 | 480.5308 | 498.5428 |

| Aragón | pv_read_N | 1797 | |||||

| Aragón | pv_readalt_mean | 489.3574 | 4.768528 | 102.62 | 0.000 | 480.0113 | 498.7036 |

| Aragón | pv_readalt_N | 1797 | |||||

| Aragón | difere | -.1793783 | .4479969 | -0.40 | 0.689 | -1.057436 | .6986794 |

| Asturias | pv_read_mean | 494.6758 | 3.885189 | 127.32 | 0.000 | 487.0609 | 502.2906 |

| Asturias | pv_read_N | 1896 | |||||

| Asturias | pv_readalt_mean | 491.6436 | 4.040386 | 121.68 | 0.000 | 483.7246 | 499.5627 |

| Asturias | pv_readalt_N | 1896 | |||||

| Asturias | difere | -3.032141 | .4074045 | -7.44 | 0.000 | -3.830639 | -2.233643 |

| Baleares | pv_read_mean | 478.7348 | 4.183915 | 114.42 | 0.000 | 470.5345 | 486.9352 |

| Baleares | pv_read_N | 1723 | |||||

| Baleares | pv_readalt_mean | 475.8325 | 4.094693 | 116.21 | 0.000 | 467.8071 | 483.858 |

| Baleares | pv_readalt_N | 1723 | |||||

| Baleares | difere | -2.902305 | .5178243 | -5.60 | 0.000 | -3.917221 | -1.887388 |

| Canarias | pv_read_mean | 471.7291 | 3.857218 | 122.30 | 0.000 | 464.1691 | 479.2891 |

| Canarias | pv_read_N | 1790 | |||||

| Canarias | pv_readalt_mean | 468.2864 | 3.835062 | 122.11 | 0.000 | 460.7698 | 475.8029 |

| Canarias | pv_readalt_N | 1790 | |||||

| Canarias | difere | -3.442751 | .3406474 | -10.11 | 0.000 | -4.110408 | -2.775095 |

| Cantabria | pv_read_mean | 483.0237 | 4.333965 | 111.45 | 0.000 | 474.5293 | 491.5181 |

| Cantabria | pv_read_N | 1880 | |||||

| Cantabria | pv_readalt_mean | 494.1387 | 4.118407 | 119.98 | 0.000 | 486.0668 | 502.2106 |

| Cantabria | pv_readalt_N | 1880 | |||||

| Cantabria | difere | 11.11499 | 2.016134 | 5.51 | 0.000 | 7.16344 | 15.06654 |

| Castilla y León | pv_read_mean | 496.5328 | 4.683635 | 106.01 | 0.000 | 487.3531 | 505.7126 |

| Castilla y León | pv_read_N | 1876 | |||||

| Castilla y León | pv_readalt_mean | 497.8215 | 4.900396 | 101.59 | 0.000 | 488.2169 | 507.4261 |

| Castilla y León | pv_readalt_N | 1876 | |||||

| Castilla y León | difere | 1.288705 | .7953758 | 1.62 | 0.105 | -.2702032 | 2.847613 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | pv_read_mean | 477.952 | 4.880844 | 97.92 | 0.000 | 468.3857 | 487.5183 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | pv_read_N | 1832 | |||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | pv_readalt_mean | 476.3575 | 5.085931 | 93.66 | 0.000 | 466.3892 | 486.3257 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | pv_readalt_N | 1832 | |||||

| Castilla-La Mancha | difere | -1.594553 | .5407023 | -2.95 | 0.003 | -2.65431 | -.5347955 |

| Cataluña | pv_read_mean | 484.3267 | 4.287873 | 112.95 | 0.000 | 475.9227 | 492.7308 |

| Cataluña | pv_read_N | 1690 | |||||

| Cataluña | pv_readalt_mean | 482.3179 | 4.488378 | 107.46 | 0.000 | 473.5209 | 491.115 |

| Cataluña | pv_readalt_N | 1690 | |||||

| Cataluña | difere | -2.008801 | .6203864 | -3.24 | 0.001 | -3.224736 | -.7928659 |

| Extremadura | pv_read_mean | 463.9754 | 5.591467 | 82.98 | 0.000 | 453.0163 | 474.9345 |

| Extremadura | pv_read_N | 1816 | |||||

| Extremadura | pv_readalt_mean | 460.6949 | 5.759329 | 79.99 | 0.000 | 449.4068 | 471.9829 |

| Extremadura | pv_readalt_N | 1816 | |||||

| Extremadura | difere | -3.280551 | .564458 | -5.81 | 0.000 | -4.386868 | -2.174233 |

| Galicia | pv_read_mean | 493.8737 | 3.313901 | 149.03 | 0.000 | 487.3786 | 500.3688 |

| Galicia | pv_read_N | 1934 | |||||

| Galicia | pv_readalt_mean | 495.7443 | 3.196672 | 155.08 | 0.000 | 489.479 | 502.0097 |

| Galicia | pv_readalt_N | 1934 | |||||

| Galicia | difere | 1.870658 | .8826824 | 2.12 | 0.034 | .1406326 | 3.600684 |

| La Rioja | pv_read_mean | 467.4523 | 2.804815 | 166.66 | 0.000 | 461.9549 | 472.9496 |

| La Rioja | pv_read_N | 1494 | |||||

| La Rioja | pv_readalt_mean | 477.9292 | 3.077152 | 155.32 | 0.000 | 471.8981 | 483.9603 |

| La Rioja | pv_readalt_N | 1494 | |||||

| La Rioja | difere | 10.4769 | .4821893 | 21.73 | 0.000 | 9.531826 | 11.42197 |

| Madrid | pv_read_mean | 473.7915 | 3.328186 | 142.36 | 0.000 | 467.2684 | 480.3146 |

| Madrid | pv_read_N | 5015 | |||||

| Madrid | pv_readalt_mean | 485.9054 | 2.818756 | 172.38 | 0.000 | 480.3807 | 491.4301 |

| Madrid | pv_readalt_N | 5015 | |||||

| Madrid | difere | 12.1139 | 1.395589 | 8.68 | 0.000 | 9.378598 | 14.84921 |

| Murcia | pv_read_mean | 481.265 | 4.731576 | 101.71 | 0.000 | 471.9913 | 490.5387 |

| Murcia | pv_read_N | 1682 | |||||

| Murcia | pv_readalt_mean | 478.355 | 4.960637 | 96.43 | 0.000 | 468.6323 | 488.0777 |

| Murcia | pv_readalt_N | 1682 | |||||

| Murcia | difere | -2.909961 | .6443936 | -4.52 | 0.000 | -4.172949 | -1.646972 |

| Navarra | pv_read_mean | 471.8186 | 5.431639 | 86.86 | 0.000 | 461.1728 | 482.4644 |

| Navarra | pv_read_N | 1728 | |||||

| Navarra | pv_readalt_mean | 486.8177 | 5.870621 | 82.92 | 0.000 | 475.3115 | 498.3239 |

| Navarra | pv_readalt_N | 1728 | |||||

| Navarra | difere | 14.99916 | 1.635343 | 9.17 | 0.000 | 11.79395 | 18.20437 |

| País Vasco | pv_read_mean | 475.2566 | 3.342334 | 142.19 | 0.000 | 468.7058 | 481.8075 |

| País Vasco | pv_read_N | 3605 | |||||

| País Vasco | pv_readalt_mean | 482.1512 | 3.209735 | 150.22 | 0.000 | 475.8602 | 488.4422 |

| País Vasco | pv_readalt_N | 3605 | |||||

| País Vasco | difere | 6.89459 | 1.199311 | 5.75 | 0.000 | 4.543984 | 9.245197 |

| Comunidad Valenciana | pv_read_mean | 472.6889 | 4.517413 | 104.64 | 0.000 | 463.835 | 481.5429 |

| Comunidad Valenciana | pv_read_N | 1753 | |||||

| Comunidad Valenciana | pv_readalt_mean | 469.3733 | 4.435609 | 105.82 | 0.000 | 460.6797 | 478.067 |

| Comunidad Valenciana | pv_readalt_N | 1753 | |||||

| Comunidad Valenciana | difere | -3.315583 | .6460696 | -5.13 | 0.000 | -4.581857 | -2.04931 |

| Ceuta | pv_read_mean | 403.9273 | 5.159777 | 78.28 | 0.000 | 393.8143 | 414.0403 |

| Ceuta | pv_read_N | 387 | |||||

| Ceuta | pv_readalt_mean | 398.4453 | 5.423275 | 73.47 | 0.000 | 387.8159 | 409.0748 |

| Ceuta | pv_readalt_N | 387 | |||||

| Ceuta | difere | -5.481986 | .9850373 | -5.57 | 0.000 | -7.412623 | -3.551348 |

| Melilla | pv_read_mean | 437.9991 | 4.880427 | 89.75 | 0.000 | 428.4336 | 447.5646 |

| Melilla | pv_read_N | 279 | |||||

| Melilla | pv_readalt_mean | 431.216 | 5.21072 | 82.76 | 0.000 | 421.0032 | 441.4288 |

| Melilla | pv_readalt_N | 279 | |||||

| Melilla | difere | -6.783103 | .7716942 | -8.79 | 0.000 | -8.295596 | -5.27061 |

Key Terms:

- pv_read_mean: the average reading performance scores for the Autonomous Community published by the OECD

- pv_read_mean: refers to the mean reading performance score of the Autonomous Community excluding the RF results. These data are available on request from the OECD.

- pv_read_N: sample size considered.

- difere: represents the difference between the mean values depending on whether the RF are included or not, calculated as pv_readalt_mean – pv_read_mean.

References

Anghel, E., Khorramdel, L. and von Davier, M. (2024). The use of process data in large-scale assessments: a literature review. Large-scale Assess Educ 12, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-024-00202-1

Avvisati, F. et al. (2024), “Item characteristics and test-taker disengagement in PISA”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 312, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7abea67b-en

Bezirhan, U., von Davier, M., and Grabovsky, I. (2020). Modeling Item Revisit Behavior: The Hierarchical Speed–Accuracy–Revisits Model. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 81(2), 363-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164420950556

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013).

De la Cruz, F. (2008). Modelos multinivel.

Fishbein, B., Foy, P., & Yin, L. (2021).

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006).

Goldhammer F, Scherer R and Greiff S (2020) Editorial: Advancements in Technology-Based Assessment: Emerging Item Formats, Test Designs, and Data Sources. Front. Psychol. 10:3047. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03047

Iñiguez-Berrozpe, T., & Marcaletti, F. (2018). Modelos lineales

multinivel en SPSS y su aplicación en investigación educativa [Linear

multilevel models in SPSS and its application in educational

research].

Merino Noé, J. (2017). La potencialidad de la Regresión Logística

Multinivel. Una propuesta de aplicación en el análisis del estado de

salud percibido.

OCDE. (2017).

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002).

Snijders, T. A., & Bosker, R. J. (2012).

Weeks, J., von Davier M. and Yamamoto K. (2016): Using response time data to inform the coding of omitted responses. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, Volume 58, (4), 671-701

Wise, S.L. (2017), Rapid-Guessing Behavior: Its Identification, Interpretation, and Implications. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 36: 52-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12165