Determinants in the choice of non-compulsory science subjects

Determinantes en la elección de materias optativas de ciencias

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-698

Radu Bogdan Toma

Universidad de Burgos

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4846-7323

Iraya Yánez Pérez

Universidad de Burgos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5260-2228

Abstract

Introduction: The curricular structure provides the option to forego scientific subjects in the final year of compulsory secondary education. This decision can prematurely disrupt formal engagement with these disciplines, typically around the ages of 14-15. Therefore, it is crucial to identify attitudinal factors that influence the selection of elective science subjects at an early age. This research focuses on two key constructs: the perception of difficulty and the associated costs of studying sciences and mathematics. Methodology: The sample comprised 214 students from 4th to 6th grade of primary education. A non-probability convenience sampling method was used to select the participants. A Likert-type instrument was administered, and its validity and reliability were assessed, proving adequate for the current sample. Data were analyzed using inferential statistics and a hierarchical logistic regression model. Results: A high percentage of students, ranging from 60.2% to 79.7%, exhibited a low interest in choosing elective science subjects during secondary education. The primary reason for this lack of interest is the perceived difficulty associated with these disciplines. Unexpectedly, the perceived cost of studying sciences increases students´ intentions, which can be explained by various theories, such as expectancy-value theory, growth mindset theory, or self-determination theory. In contrast, neither the perceived cost nor difficulty of mathematics influences students´ intentions to pursue this field. Conclusions: These findings are discouraging and highlight the urgency of designing and implementing educational programs targeted at the primary education stage to address and reverse this trend.

Keywords:

student attitude, learning difficulties, natural sciences, mathematics, elementary school, choice of studies, science education

Resumen

Introducción: La estructura curricular ofrece la opción de no cursar materias científicas en el último curso de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Esta decisión puede interrumpir prematuramente, alrededor de los 14-15 años, el contacto formal con estas disciplinas. Por tanto, resulta fundamental identificar a temprana edad los factores actitudinales que influyen en la elección de asignaturas optativas de ciencias. La presente investigación se enfoca en dos constructos clave: la percepción de dificultad y el coste asociado a las ciencias y a las matemáticas. Metodología: La muestra estuvo conformada por 214 estudiantes de 4º a 6º curso de Educación Primaria. Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico por conveniencia para seleccionar a los participantes. Se aplicó un instrumento de tipo Likert, cuya validez y confiabilidad fueron evaluadas y resultaron adecuadas para la muestra actual. Los datos fueron analizados mediante estadística inferencial y un modelo de regresión logística jerárquica. Resultados: Un alto porcentaje de los estudiantes encuestados, que oscila entre el 60.2% y el 79.7% en función del curso escolar, muestra un bajo interés por elegir asignaturas de ciencias optativas durante la secundaria. La principal razón para esta baja intención es la percepción de dificultad asociada a estas disciplinas. De manera inesperada, el coste percibido de estudiar ciencias actúa como un factor que incrementa las intenciones de los estudiantes, lo cual puede explicarse a través de diversas teorías, como la teoría de la expectativa-valor, la mentalidad de crecimiento o la teoría de la autodeterminación. En contraste, ni el coste ni la dificultad percibidos de las matemáticas influyen en las intenciones de los estudiantes de cursar esta área. Conclusiones: Estos hallazgos resultan desalentadores y ponen de manifiesto la urgencia de diseñar e implementar programas educativos focalizados en la etapa de Educación Primaria para abordar y revertir esta situación.

Palabras clave:

actitud del alumno, dificultad de aprendizaje, ciencias de la naturaleza, matemáticas, escuela primaria, elección de estudios, educación científicaIntroduction

Student interest and participation in science decline as they progress through their studies (Toma & Lederman, 2022; Tytler & Ferguson, 2023). This global and persistent trend often leads to students abandoning science after completing their compulsory secondary education. In Spain, the situation is worsened by the curriculum structure. The option to avoid science subjects in the final year of secondary education results in an early end to formal engagement with these disciplines, typically around the ages of 14-15 (Toma, 2022a). This is concerning, given the importance of scientific literacy for active citizenship (Bybee & McCrae, 2011). Attitudes toward science significantly impact academic performance, career choices, future studies, and public support for scientific research funding (Besley, 2018; Bidegain & Lukas Mujika, 2020; Newell et al., 2015). Consequently, they have become a central focus of educational research. These attitudes reflect students’ subjective evaluations of science and its study, encompassing both affective aspects (emotions and feelings) and cognitive elements (thoughts and beliefs) that shape their behavior and decisions to pursue science-related studies (Tytler & Ferguson, 2023). Despite a growing body of research, most studies focus on secondary education. However, by this stage, students´ attitudes toward science are often already deteriorating, making it difficult to reverse the trend (Carrasquilla et al., 2022; Dapía et al., 2019; Robles et al., 2015). Disinterest in science is evident from primary education onward, with notable gender differences favoring boys (Dapía et al., 2019; Toma, 2022a). Therefore, identifying the attitudinal factors that influence the scientific aspirations of primary school students is crucial (Miller, 2021). This study addresses this objective, focusing particularly on two key factors: perceived cost and difficulty. The research aims to answer the following questions:

- What is the perception of difficulty and cost of learning science and mathematics among primary school students in 4th to 6th grade? What are their intentions regarding the choice of elective scientific subjects in secondary school?

- How do the perceptions of difficulty and cost of learning science and mathematics influence primary school students´ intentions to choose elective scientific subjects in secondary school?

Theoretical underpinnings and operationalization of hypotheses

Cost represents the subjective assessment of the sacrifices associated with an activity (Eccles & Wigfield, 2023; Muenks et al., 2023). In the context of this study, the cost of studying science may involve, among other things, considerable mental effort or the forfeiting of other valued activities. This construct, initially proposed by the Expectancy-Value Theory, has been revitalized in recent research (Barron & Hulleman, 2015; Flake et al., 2015). These studies have refined and expanded its conceptualization and evaluation, demonstrating its relevance in the educational field. Research indicates that high levels of perceived cost are associated with a lower valuation of the activity being studied, as well as reduced persistence and intentions to continue with it (Eccles & Wigfield, 2023; Jiang & Rosenzweig, 2021). In the case of science, this phenomenon could help explain the lack of interest and eventual abandonment of scientific studies once they are no longer mandatory, as outlined in Hypothesis #1.

On the other hand, perceived difficulty reflects the subjective assessment of the complexity of an activity, such as studying science (Pattal et al., 2018; Toma, 2022b). According to the Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), an optimal challenge promotes a sense of competence. Activities that are either too easy or too difficult can lead to boredom, discouragement, and abandonment. A high perceived difficulty reduces student interest, negatively influencing career choices and academic achievements (Ong et al., 2022; Pattal et al., 2018). In this sense, many students, despite their initial interest, abandon scientific careers due to the high perceived difficulty of studying those (Chi et al., 2017). Therefore, perceiving the learning of science in primary education as excessively difficult may lead to frustration and disengagement in later stages, as proposed in Hypothesis #2.

Finally, it is crucial to also consider the perceived cost and difficulty of mathematics when analyzing students´ intentions to study science. Although mathematics is mandatory in secondary education, previous research suggests that its perceived cost and difficulty influence the choice to pursue scientific studies, particularly among women (Ellis et al., 2016; Wang & Degol, 2013). Therefore, it is likely that a high perceived cost, as outlined in Hypothesis #3, and a high perceived difficulty, as proposed in Hypothesis #4, of studying mathematics will also negatively impact students´ intentions to choose elective scientific subjects in secondary education.

Method

This is a quantitative research study. The design is cross-sectional, predictive, and observational, as it aims to predict the attitudinal factors that influence the intention to choose elective scientific subjects in secondary education.

Participants

A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was used, selecting two schools from the city of Burgos—one public and one private. The final sample consisted of 214 Spanish primary school students enrolled in 4th (22%), 5th (36.9%), and 6th grade (41.1%). Nearly half of the participants were girls (48.6%), and the average age was 10.34 years (SD = .91). The minimum sample size was calculated based on Ogundimu et al.´s (2016) criteria, which recommend a minimum of 10-20 events or responses per independent or predictor variable. Given a logistic regression model with six variables (as described in the following sections), a minimum of 60-120 events was estimated. The final sample size (214 subjects) provided an event rate per variable of 35.7, which far exceeded the recommended minimum.

Instruments

Data were collected using five scales based on existing instruments with evidence of validity and reliability, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). One of these scales measures the intention to choose elective science subjects, while the other two assess perceived difficulty—one applied to science and the other to mathematics. The two difficulty scales were replicated: first applied to science, then to mathematics, resulting in a total of five distinct scales. Anonymized data are available at the following link:

Dependent variable

A single-item scale developed by Toma et al. (2019) was used to measure students´ intention to choose elective science subjects in secondary education. The specific question was: "It is very likely that I will enroll in elective science subjects in Secondary Education." Previous research has demonstrated that this is a valid and reliable measure for assessing this intention, showing high consistency in responses over time. It is important to note that in the Spanish education system, formal science education begins in Primary Education. In Secondary Education, a turning point occurs: Biology and Geology are mandatory in the first and third years, Physics and Chemistry in the second and third years, and in the fourth year, both subjects become elective. Therefore, the item explicitly refers to the Secondary Education stage.

Independent variables

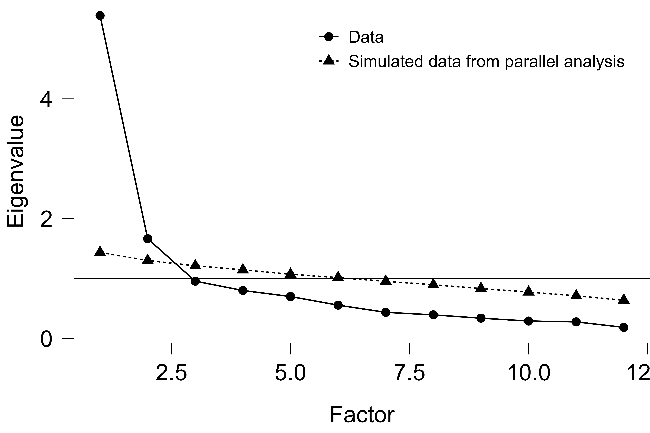

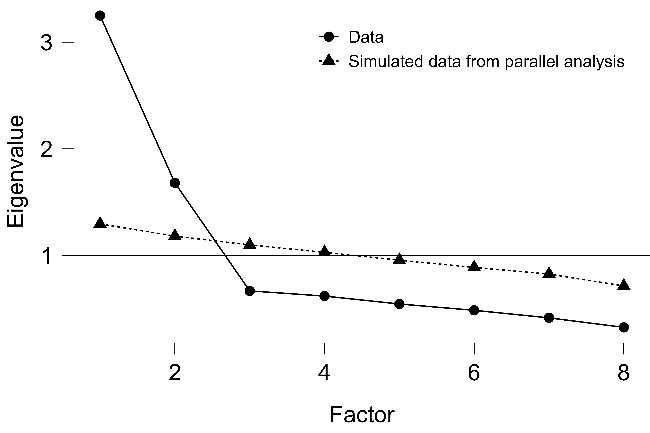

To measure the perceived cost of science and mathematics, a six-item scale for each subject was used. To measure the difficulty perceived by students in these subjects, a six-item scale for each subject was also employed (Pattal et al., 2018; Toma, 2022b). The validity and reliability of the instruments were tested for this specific sample. Both scales underwent exploratory factor analysis according to the recommendations of Ferrando et al. (2022). Specifically, (i) a polychoric correlation matrix was used, and factors were extracted using the maximum likelihood method with Oblimin oblique rotation; (ii) the parallel analysis criterion was employed to determine the optimal number of factors; and (iii) only those items with factor loadings above 0.40 and no cross-loadings between factors were retained.

Optimal sample adequacy indices were obtained: the KMO was 0.851

for the science items and 0.867 for the mathematics items, and

Bartlett´s test of sphericity was significant in both cases

(

FIGURE I. Results of the parallel analysis

a) Science-related items  |

b) Math-related items  |

|---|

TABLE I. Results of the exploratory factor analysis

| Ítems and constructs | Science | Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | I | II | |

| I. Cost | ||||

| 1. I must sacrifice a lot of my free time to be good at science/mathematics | 0.724 | -0.179 | 0.747 | -0.154 |

| 2. I must give up many things to get good grades in science/mathematics | 0.756 | -0.026 | 0.562 | 0.156 |

| 3. I need to spend a lot of time studying to get good grades in science/mathematics | 0.722 | -0.112 | 0.832 | 0.079 |

| 4. I can not spend the needed studying time to get good grades in science/mathematics | 0.630 | 0.041 | - | - |

| 5. Science/mathematics requires too much effort from me | 0.728 | 0.230 | - | - |

| 6. Doing science/mathematics homework takes too much of my time | 0.712 | 0.176 | - | - |

| II. Perceived difficulty | ||||

| 1. I am not good at science/mathematics | -0.079 | 0.737 | -0.036 | 0.667 |

| 2. I struggle with science/mathematics | 0.150 | 0.645 | 0.019 | 0.684 |

| 3. I get bad grades in science/mathematics | -0.039 | 0.703 | -0.039 | 0.709 |

| 4. Science/mathematics seems difficult to me | 0.318 | 0.469 | 0.195 | 0.624 |

| 5. I find it hard to understand science/mathematics lessons | 0.048 | 0.560 | - | - |

| 6. I cannot do the science/mathematics homework well | 0.056 | 0.633 | 0.195 | 0.667 |

The reliability of the scales was evaluated using McDonald´s Omega coefficient, as it is more appropriate than Cronbach´s Alpha for ordinal-type items (Hayes & Coutts, 2020). The results indicated adequate reliability for both the cost scales (science = 0.83, mathematics = 0.74) and the perceived difficulty scales (science = 0.78, mathematics = 0.74). In summary, the instruments used were valid and reliable for the present sample, allowing for the collection of accurate information regarding students´ perceptions of these subjects.

Control variables

The gender and age of the students were used as control variables.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis was used to examine the perceived

difficulty and cost associated with science and mathematics. The

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was statistically significant for all

independent variables, indicating that the normality assumption

required for parametric inferential tests was not met. Therefore,

non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney

Results

Descriptive analysis

Table II presents the perceived cost and difficulty of science

and mathematics according to sociodemographic variables. Overall,

students perceive both science and mathematics as relatively low in

cost and difficulty. The cost associated with mathematics is higher

than that of science, and in terms of difficulty, science is seen as

slightly easier than mathematics. When breaking down the results by

gender, boys perceive a higher cost in studying science

(

TABLE II. Cost and perceived difficulty of science and mathematics

| Sociodemographic variables | Cost of science | Cost of mathematics | Difficulty of science | Difficulty of mathematics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | 2.27 (0.84) | 2.59 (0.96) | 2.06 (0.68) | 2.15 (0.73) |

| Boys | 2.40 (0.82) | 2.68 (0.97) | 2.04 (0.64) | 2.15 (0.76) |

| Girls | 2.13 (0.85) | 2.50 (0.96) | 2.08 (0.72) | 2.14 (0.69) |

| 4th grade | 2.44 (0.74) | 2.79 (0.93) | 2.10 (0.70) | 2.19 (0.80) |

| 5th grade | 2.19 (0.87) | 2.53 (0.99) | 2.03 (0.66) | 2.17 (0.70) |

| 7th grade | 2.25 (0.86) | 2.54 (0.96) | 2.07 (0.69) | 2.10 (0.71) |

Mean (standard deviation)

Table III presents the intentions to choose elective science subjects in secondary education according to sociodemographic variables. The majority of students show low intentions to choose elective science subjects in secondary education. When analyzing the results by gender, both boys and girls display similar patterns in terms of low intentions (p > 0.05). However, the distribution of intentions varies considerably according to the school year (p = 0.023), albeit with a small effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.19). A significant decrease in intentions is observed in 5th grade, followed by a recovery in 6th grade.

TABLE III. Intentions to choose science electives in secondary school.

| Sociodemographic variables | Low intentions | High intentions |

|---|---|---|

| All participants | 68.7% | 31.3% |

| Boys | 68.2% | 31.8% |

| Girls | 69.2% | 30.8% |

| 4th grade | 66% | 34% |

| 5th grade | 79.7% | 20.3% |

| 7th grade | 60.2% | 39.8% |

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis

Table IV presents the results of the hierarchical logistic

regression model. The initial model, which included only the control

variables (gender and age), did not show a significant fit to the

data (χ² (2, N = 214) = 1.362,

TABLE IV. Hierarchical logistic regression análisis

| Predictors | Step 1 | Step 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Exp(B) | B | Exp(B) | |

| Gender | 0.047 | 1.048 | -0.094 | 0.910 |

| Age | 0.187 | 1.206 | 0.248 | 1.282 |

| Cost of science | - | - | 0.528* | 1.695 |

| Coste of mathematics | - | - | -0.222 | 0.801 |

| Difficulty of science | - | - | -1.013** | 0.363 |

| Difficulty of mathematics | - | - | -0.008 | 0.992 |

*

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between perceived cost, difficulties in science and mathematics, and the intention to take elective science subjects in secondary school among primary school students. This research contributes to the existing literature by analyzing a crucial stage in the development of scientific attitudes (Dapía et al., 2019; Miller, 2021).

The results indicate that students perceive mathematics as slightly more demanding than science, both in terms of cost and difficulty. Boys report higher costs in both science and mathematics, although the perception of difficulty is similar across genders. As they progress through primary school, the perceived cost in both areas decreases, but the perception of difficulty remains low and consistent. However, a high percentage of students, especially in 5th grade, show little intention to take elective science subjects in secondary school. This trend reveals an early decline in scientific attitudes and aspirations, which aligns with both international and national research (Toma, 2020; Tytler & Ferguson, 2023). Nevertheless, the results differ by gender. Previous studies suggest more positive attitudes toward science among boys than girls (Carrasquilla et al., 2022; Dapía et al., 2019). However, this study presents a contrary finding: boys reported higher levels of perceived cost in both areas. This discrepancy could be attributed to the different conceptualizations and instruments used to measure attitudes toward science. The term "attitude" serves as an umbrella for a wide range of constructs, such as self-efficacy, enjoyment, perceived relevance, and interest (Toma & Lederman, 2022). However, the cost aspect has been less explored (Flake et al., 2015), which may explain the differences found in contrast to previous studies.

On the other hand, the regression analysis indicates that the perception of cost and difficulty in science influences the intention to take elective science subjects in secondary school. However, these same factors in mathematics do not show a significant impact. This difference could be attributed to the characteristics of both subjects in primary school. Science is typically approached with a more conceptual focus, while mathematics centers on basic numerical and geometric skills. Additionally, the lesser presence of advanced mathematics in primary school science could reduce the association between the two areas as perceived by students. Future studies in secondary school, where the connection between science and mathematics is more evident, could further explore this relationship.

An unexpected finding was the positive effect of the perceived cost of science on students´ intentions. Specifically, the perceived cost significantly increased the intention to enroll in elective science subjects. Several explanations could support these results. According to the Expectancy-Value Model (Eccles & Wigfield, 2023), academic decisions are influenced by expectations of success and the value attributed to an activity. If a student perceives a high value in studying science (such as success or satisfaction), their intention to enroll will increase, even in the face of high costs. Additionally, students with a growth mindset may interpret the perceived cost of science as an opportunity to develop their skills (Dweck, 2006). This mindset, characterized by the belief in the malleability of abilities, is associated with greater persistence and a lower likelihood of avoiding tasks that require effort (Mrazek et al., 2018). As a result, these students may be more willing to choose science subjects despite the perceived costs.

Finally, these results could also be explained in light of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000). This theory distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. If a student is intrinsically motivated by science, the perceived cost may be viewed as an overcomeable obstacle, even a satisfying one, as it is part of an activity they find rewarding. Additionally, overcoming challenges can enhance the sense of competence, a central element in this theory. A greater sense of competence, in turn, strengthens intrinsic motivation and increases intentions. In this regard, students who perceive their studies as an investment in their professional future and who strive to meet their academic obligations are more likely to complete their studies (Abiétar López et al., 2023). However, the proposed explanations are hypothetical and require further research for confirmation.

These findings have important educational implications. At the educational level, it is crucial to intervene early, in primary education, to foster positive attitudes toward science. Given the low intention of many students to take elective science subjects in secondary school, primarily due to their perception of difficulty, pedagogical strategies should be implemented to reduce this perception, enabling meaningful learning. In this regard, it is essential to design teaching materials and activities that align with students´ capabilities. Although there are resources—both analog and digital—backed by research in science education (Yánez-Pérez et al., 2024a), their use in classrooms in Spain is limited. Therefore, the results also highlight the need for more effective educational policies (Yánez-Pérez et al., 2024b). It is suggested that initial and ongoing teacher training be improved to provide educators with the necessary pedagogical tools to foster positive attitudes toward science from an early age. The growth mindset theory (Dweck, 2006) can guide these efforts by teaching that scientific understanding and ability are not innate, but rather developed through practice and effort. Additionally, cognitive load theory is essential for planning effective learning, and avoiding the overload of working memory with overly complex or trivial tasks (Sweller, 2020).

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. Convenience sampling limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations and educational contexts. Additionally, while the instruments used have demonstrated validity and reliability, measuring cost as a unidimensional construct could be a limitation. Recent research with secondary and tertiary students indicates that cost is a multidimensional construct. In fact, the interaction between cost and the intention to enroll in science suggests the need for more comprehensive instruments that reflect the complex conceptualization of this construct.

Conclusions

The study reveals that a high proportion of primary school students show low intention to enroll in elective science subjects in secondary school, primarily due to the perception of difficulty in the subject. It is also observed that boys perceive a higher cost in both science and mathematics, suggesting the need for specific educational measures to address these differences. Finally, a higher perceived cost in science appears to increase the intention to take elective courses, which could indicate that perceived challenges may be viewed as motivating opportunities; an aspect that opens avenues for future research. Overall, these findings highlight the urgency of intervening to improve interest in science starting from the primary education stage.

Referencias bibliográficas

Abiétar López, M., Bernad i Garcia, J. C., Córdoba Iñesta, A. I.,

Giménez Urraco, E., Meri Crespo, E., y Navas Saurin, A. A. (2023).

Factores diferenciales en los itinerarios en Formación Profesional:

un estudio longitudinal.

Barron, K. E., y Hulleman, C. S. (2015). Expectancy-Value-Cost

Model of Motivation.

Besley, J. C. (2018). The National Science Foundation’s science

and technology survey and support for science funding, 2006–2014.

Bidegain, G., y Lukas Mujika, J. F. (2020). Exploring the

relationship between attitudes toward science and PISA scientific

performance.

Bybee, R. W., y McCrae, B. (2011). Scientific literacy and

student attitudes: Perspectives from PISA 2006 science.

Carrasquilla, O. M., Pascual, E. S., y Roque, I. M. S. (2022). La

brecha de género en la Educación STEM.

Chi, S., Wang, Z., Liu, X., y Zhu, L. (2017). Associations among

attitudes, perceived difficulty of learning science, gender,

parents’ occupation and students’ scientific competencies.

Dapía, M., Escudero-Cid, R., y Vidal, M. (2019). ¿Tiene género la

ciencia? Conocimientos y actitudes hacia la Ciencia en niñas y niños

de Educación Primaria.

Dweck, C. S. (2006).

Eccles, J. S., y Wigfield, A. (2023). Expectancy-value theory to

situated expectancy-value theory: Reflections on the legacy of 40+

years of working together.

Ellis, J., Fosdich, B. K., y Rasmussen, C. (2016). Women 1.5

times more likely to leave STEM pipeline after calculus compared to

men: Lack of mathematical confidence a potential culprit.

Ferrando, P. J., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Hernández-Dorado, A., y Muñiz,

J. (2022). Decálogo para el análisis factorial de los ítems de un

test [Decalogue for the factor analysis of test items].

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., y

Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of

expectancy-value theory.

Hayes, A. F., y Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use Omega rather than

Cronbach’s Alpha for estimating reliability. But….

Iacobucci, D., Posavac, S. S., Kardes, F. R., Schneider, M. J., y

Popovich, D. L. (2015). The median split: Robust, refined, and

revived.

Jiang, Y., y Rosenzweig, E. Q. (2021). Using cost to improve

predictions of adolescent students’ future choice intentions,

avoidance intentions, and course grades in mathematics and English.

Miller, B. (2021). Developing interest in STEM careers: The need

to incorporate STEM in early education.

Mrazek, A. J., Ihm, E. D., Molden, D. C., Mrazek, M. D.,

Zedelius, C. M., y Schooler, J. W. (2018). Expanding minds: Growth

mindsets of self-regulation and the influences on effort and

perseverance.

Muenks, K., Miller, J. E., Schuetze, B. A., y Whittaker, T. A.

(2023). Is cost separate from or part of subjective task value? An

empirical examination of expectancy-value versus

expectancy-value-cost perspectives.

Newell, A. D., Zientek, L. R., Tharp, B. Z., Vogt, G. L., y

Moreno, N. P. (2015). Students’ attitudes toward science as

predictors of gains on student content knowledge: Benefits of an

after-school program.

Ogundimu, E. O., Altman, D. G., y Collins, G. S. (2016). Adequate

sample size for developing prediction models is not simply related

to events per variable.

Ong, A. K. S., Prasetyo, Y. T., Pinugu, J. N. J., Chuenyindee,

T., Chin, J., y Nadlifatin, R. (2022). Determining factors

influencing students’ future intentions to enroll in

chemistry-related courses: integrating self-determination theory and

theory of planned behavior.

Ong, A. K. S., Prasetyo, Y. T., Pinugu, J. N. J., Chuenyindee,

T., Chin, J., y Nadlifatin, R. (2022). Determining factors

influencing students’ future intentions to enroll in

chemistry-related courses: integrating self-determination theory and

theory of planned behavior.

Robles, A., Solbes, J., Cantó, J. R., y Lozano, Ó. R. (2015).

Actitudes de los estudiantes hacia la ciencia escolar en el primer

ciclo de la Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria.

Ryan, R. M., y Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and

the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and

well-being.

Sweller, J. (2020). Cognitive load theory and educational

technology.

Toma, R. B. (2020). Revisión sistemática de instrumentos de

actitudes hacia la ciencia (2004-2016) [Systematic review of

attitude toward science instruments (2004-2016)].

Toma, R. B. (2022a). Elementary school students’ interests and

attitudes towards biology and physics.

Toma, R. B. (2022b). Perceived difficulty of school science and

cost appraisals: A valuable relationship for the STEM pipeline?

Toma, R. B., y Lederman, N. G. (2022). A comprehensive review of

instruments measuring attitudes toward science.

Toma, R. B., y Meneses-Villagrá, J. A. (2019). Validation of the

single-items Spanish-school science attitude survey (S-SSAS) for

elementary education.

Tytler, R., y Ferguson, J. P. (2023). Student attitudes,

identity, and aspirations toward science. En N. G. Lederman, D. L.

Zeidler, y J. S. Lederman (Eds.),

Wang, M. T., y Degol, J. (2013). Motivational pathways to STEM

career choices: Using expectancy-value perspective to understand

individual and gender differences in STEM fields.

Yánez-Pérez, I., Toma, R. B., y Meneses-Villagrá, J. Á. (2024a).

Design and usability evaluation of a mobile app for elementary

school inquiry-based science learning.

Yánez-Pérez, I., Toma, R. B., y Meneses-Villagrá, J. A. (2024b).

La brecha digital en la enseñanza de las ciencias en España durante

las leyes educativas LOE y LOMCE.

Información de contacto / Contact info: Radu Bogdan Toma. Universidad de Burgos, Facultad de Educación, Departamento de Didácticas Específicas. E-mail: rbtoma@ubu.es