Evaluation of the Teacher Professional Development System on Student Results in Chile

Evaluación Del Sistema De Desarrollo Profesional Docente Sobre Los Resultados De Los Alumnos en Chile

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-409-695

Felipe Monjes García

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-7043-2584

Abstract

In 2017, Law No. 20,903 came into force, to modify the Statute of Education Professionals, implementing the Teacher Professional Development System (SDPD) in the Chilean Education System. Among the modifications introduced is a system of economic incentives for teachers who belong to the public system, which can substantially modify their remunerations. The system is based on recognizing the social importance of teaching work and the theory of incentives. In this sense, international evidence points to a direct relationship between teachers´ salaries and the results of their students during their school career in standardized assessments. Through a difference-in-differences estimation, with SIMCE language and mathematics test data of the 2016 and 2018 cohorts applied to fourth-grade and sixth-grade students nationwide, respectively, the impact of the incentive policy derived from the Teacher Professional Development System on teachers in the public system was analysed, in contrast to those in the subsidized private sector. Thus, for various estimates, null or negative results are obtained on the results of students in standardized tests, whose teachers are part of the analysed policy, evidencing a more statistically robust effect in cases where the result variable is the mathematics evaluation. After reviewing the results of the different estimation models, it seems pertinent to maintain monitoring regarding the effects of the policy and its generated incentives for teachers. In addition, it is important to incorporate insights from similar strategies implemented in other systems, for example, the cases of performance incentives that are not permanent and are constantly evaluated to maintain and renew them.

Keywords:

Incentives, Academic Achievement, Wage, Public Policy, Evaluation

Resumen

Durante el año 2017 entró en vigor la Ley Nº20.903, la cual modifica el Estatuto de Profesionales de la Educación, implementando el Sistema de Desarrollo Profesional Docente (SDPD) en el Sistema Educacional Chileno. Entre las modificaciones introducidas se encuentra un sistema de incentivos económicos a los docentes que pertenecen al sistema público, el cual puede llegar a modificar sustancialmente sus remuneraciones. El postulado bajo el cual se basa este incremento radica en reconocer la importancia social de la labor docente y la teoría de los incentivos. En este sentido, la evidencia internacional apunta en una relación directa entre el salario de los docentes y los resultados de sus alumnos durante su trayectoria escolar en evaluaciones estandarizadas. Mediante una estimación de diferencias en diferencias, con datos de la prueba SIMCE de lenguaje y matemáticas de las cohortes 2016 y 2018 aplicadas a los alumnos de cuarto año básico y sexto año básico a nivel nacional, respectivamente, se analizó el impacto de la política de incentivos derivada del Sistema de Desarrollo Profesional Docente a los profesores del sistema público, en contraste a los del sector particular subvencionado. Es así como para diversas estimaciones se obtienen resultados nulos o negativos sobre los resultados de los alumnos en pruebas estandarizadas, cuyos profesores son parte de la política analizada, evidenciando un efecto más robusto estadísticamente en los casos que la variable de resultado es la evaluación de matemáticas. Luego de revisar los resultados de los diferentes modelos de estimación, parece pertinente mantener un monitoreo respecto a los efectos de la política y sus incentivos generados a los docentes, además de incorporar la visión de estrategias similares en otros sistemas, por ejemplo, los casos de incentivos por rendimiento que no son permanentes y son evaluados constantemente para mantenerlos y renovarlos.

Palabras clave:

Incentivos, Resultados Académicos, Salarios, Política Pública, EvaluaciónIntroduction

Good teachers matter—there is no doubt about that. Several studies show that high-performing teachers can significantly influence student outcomes in standardized tests (Fryer et al., 2018).

There are diverse strategies to ensure that the best teachers are present in schools; one of them is to “hire the best.” While this may seem like an obvious approach, in practice it is not, as identifying the best teachers “ex-ante” is not a simple task. A second approach involves investing in human capital improvement through training. In this regard, since the implementation of the Preferential School Subsidy (Subvención Escolar Preferencial - SEP) in Chile—which aims to provide increased resources for vulnerable students—funding for this purpose has grown. A third approach is to associate incentives with teachers, aiming to improve their performance. This policy approach constitutes the core focus of the present study.

The diversity of strategies implemented across education systems globally makes the evaluation of its impact and relevance necessary, once a course of action is chosen.

The general objective of this study is to assess whether the implementation of a Teacher Professional Development System (Sistema de Desarrollo Profesional Docente - SDPD), initiated in Chile in 2017, influences students´ academic performance in standardized tests.

The first section of the study contextualizes the issue by examining historical student performance in standardized assessments, considering the administrative dependence of schools. This is followed by a conceptual definition of the Incentive Theory and the characterization of the structure of the SDPD (Teacher Career Path).

The next section presents the methodology, the data analysis and policy evaluation. Followed by the analysis of results which includes a descriptive characterisation of the students and teachers who are part of the policy, and an impact assessment of the policy.

Finally, the study concludes with key findings and proposals for possible extensions of the work.

The Chilean School System and Incentives

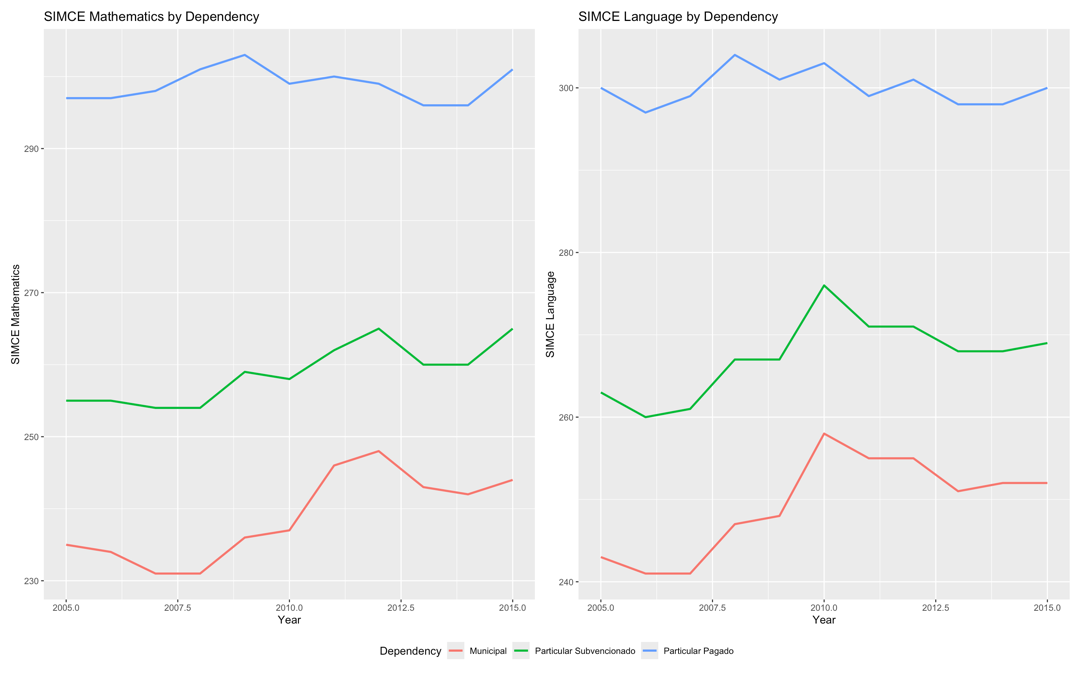

The persistently low performance of Chilean municipal schools in standardized assessments is a regrettable constant within the education system. When analyzing the evolution of SIMCE results (a standardized test administered at various educational levels across Chile), both in mathematics and language, it is evident that private and subsidized private schools consistently outperform municipal schools year after year, as shown in Graph 1:

FIGURE I: Evolution of SIMCE Scores – 4th Grade

Source: Compiled by the authors.based on data from the Education Quality Agency.

There are multiple explanations for this phenomenon, including students’ socioeconomic background and vulnerability, the rural nature of many schools, the selective admission capacity of private and subsidized private institutions, and the quality and incentive structure of teachers.

As such, several public policies have aimed to improve teacher quality, allocating significant resources to professional development programs, including training in curriculum evaluation, pedagogy, and other areas. However, at least within the municipal sector, these initiatives appear to have fallen in terms of improving student learning outcomes.

Consequently, in 2017, Chile implemented the Teacher Professional Development System (SDPD) within its education system—a reform that, to date, lacks comprehensive evaluation regarding its impact on student outcomes.

Incentive Theory

Unlike the so-called "Exact Sciences," the Social Sciences deal with individuals who make decisions influenced by beliefs, personal circumstances, others behaviour, among others. This makes difficult to predict behaviours, highlighting the need for an analytical framework about decision-making processes and outcomes prediction of those decisions.

Failing to consider incentives in individual decision-making can lead to completely misguided predictions of behaviour. A clear example is the British colonization of India, where one of their greatest challenges was not military resistance, but venomous cobras— This gave rise to the so-called ´cobra effect.´(Sala-I-Martín, 2019).

With respect to incentive theory, a significant contribution comes from principal-agent model, where the teacher (agent) focuses their efforts on tasks that are evaluated and rewarded by the principal, neglecting those that are not subject to economic incentives (Holmstrom & Milgrom, 1991).

On the other side, the perspective of efficiency wage schemes assumes that individuals (including teachers) seek to maximize their welfare, leading problems for principals agency, particularly when information is asymmetric. These issues can be mitigated through contracts that evaluate performance—such as student results on standardized assessments or student pass rates—and implement efficient incentive systems (Holmström, 1979).

Furthermore, by introducing the possibility of higher salaries based on teacher performance, allows a competitive “market” for highly qualified individuals interested in public positions, as long as the salaries are attractive to comparable positions in the subsidized or private sectors. Recruiting highly efficient teachers would enhance school management by attracting talent to the municipal/public sector and encouraging self-selection dynamics. This scenario activates mechanisms such as signaling, the value of certifications (academic degrees and their origin), and the pursuit of returns on these credentials, among others.

In terms of contract design, proposing a greater emphasis on performance-based pay and a reduction in fixed salary components leads to a linear salary function of the form:

where “k” is the base component and “m” represents the variable component dependent on goal achievement (x). This formula seeks to reduce moral hazard in management by increasing the “penalty” for deviating from the objectives set by the principal (Dixit, 2002).

A well-structured incentive system can certainly predict better teacher performance. However, this should not come at the expense of monitoring other elements outside the incentive scheme design that still affect students, such as school climate and student well-being.

International Evidence

There is broad consensus regarding the importance of education as one of the main drivers of national development. Some development models even place human capital at the centre of the development leap that countries can make. In this regard, Gary Becker (1993) argued that economic growth can be explained not only by the physical and financial capital, but also by the incorporation of scientific and technological advancements to improve productivity, making human capital a key component. Today, Becker’s proposals are fully accepted, with human capital now integrated into formal development models (Barro & Sala-I-Martín, 2018). In this context, it is crucial to understand the relationships embedded in the economics of education for public policy decision-making.

Amain concern for the economics of education has been identifying the factors that explain student performance on standardized assessments. Evidence shows that if students with similar baseline skills and knowledge are taught by teachers of different quality—one high-performing and the other low-performing—after three years, significant differences will emerge in their learning outcomes (Barber & Mourshed, 2007). Thus, factors such as the selectivity of entry into teacher superior education programs, average per-student expenditure, and teacher salaries all feed into a production function that helps explain both, teacher performance and student achievement.

Regarding teacher salaries, this variable is clearly related to the kind of professionals who are drawn to the teaching profession—both at entry and throughout their career trajectory. Countries with high-performing school systems tend to offer starting salaries for teachers that are above the per capita GDP in their respective contexts (Barber & Mourshed, 2007). This aligns with evidence from Australia, where Leigh (2012) found that increasing teacher salaries promote higher-achieving secondary school students to pursue degrees in education.

The idea of a positive correlation between teacher pay and performance is frequently used in the design of policies aiming to improve student outcomes on standardized tests (Hanushek et al., 2018). These researchers, after analyzing data from 31 countries, concluded that teacher pay is positively correlated with the proportion of high-performing secondary students who choose to become teachers—consistent with Leigh´s findings in Australia.

On the other hand, Bueno and Sass (2018), explored whether performance-based bonuses help retain teachers in the system. They found that higher salaries do make the teaching profession more attractive in terms of retention, but do not generate sufficient incentives for specialization in subjects like mathematics or science, areas that often face teacher shortages.

Contrary to the above, a regression discontinuity analysis conducted in the state of Washington did not find evidence of a causal relationship between economic incentives (bonuses) and significant improvements in student outcomes on standardized tests (Bueno & Saas, 2018).

In the Latin American context, a study using difference-in-differences and triple-difference techniques in public schools in the state of São Paulo, found that an incentive program positively impacted student achievement (Lépine, 2022). Conversely, Bellés-Obrero and Lombardi (2022) evaluated a teacher bonus policy and found no significant effect on the test scores of students whose teachers received the incentive.

Chilean Context

The study of the impact of teacher salaries on student outcomes is not new in the international literature, nor in the Chilean case. In the late 1990s, Patricio Rojas (1998) presented a study concluding the negative impact of low starting salaries on the “teacher labor market” and the limited prospects for salary progression, condition prevalent at the time.

This situation persisted for over two decades, generating academic interest in the topic. In 2015, Eyzaguirre and Ochoa (2015) presented recommendations for designing a career path system for teachers, including the creation of incentive systems to attract better professionals into both, school and early childhood education.

Additional literature follow a similar line. For instance, in the early 2000s, Le-Foulon (2000), identified similar results to Eyzaguirre and Ochoa fifteen years later, regarding the need to modify the design of the incentive system. Meanwhile, Bravo, Flores, and Medrano (2010), identify that teachers´ greater skills are recognized monetarily in the subsidized private sector, but not in the municipal sector.

From a qualitative perspective, studies have explored teachers´ perceptions of their own salaries and their individual impact with a social effect. These studies suggest that teachers’ have lower salary wages, compared to other professionals with similar experience (Acuña Ruz, 2015). This could affect their work performance and student learning.

To sum up, there is substantial consensus in the Chilean academic community regarding teachers’ salary conditions influence their performance and, consequently, student outcomes. This has created pressure to reform teacher compensation structures, ultimately resulting in legal changes focused on the Teacher Statute.

Teacher Professional Development System

In 2017, Law No. 20,903 came into effect, establishing the Teacher Professional Development System (SDPD). It includes significant changes to the Teacher Statute, including the creation of a structured "Teacher Career Path." Among its provisions, the law modifies the incentive mechanism for education professionals (Rivera, 2018) and establishes categories (or "levels") for teachers (CPEIP Ministerio de Educación, 2020).

Article 19 of the Teacher Statute highlights the SDPD’s principle to recognize and promote the professional development of educators by providing financial incentives for progression within the system. In addition, it promotes the professionalization of teaching in Chile, emphasizing autonomy, ongoing training, ethical commitment, and responsibility.

In general terms, the SDPD comprises two subsystems: one focused on recognition and promotion of professional development, and another on formative support.

Recognition and Promotion Subsystem encompasses an assessment process (which takes into account teaching experience and competencies) and a progression mechanism through various levels, allowing teachers to access different remuneration tiers.

The assessment process aims to certify that teachers have the necessary disciplinary and pedagogical knowledge for their subject area, with a strong emphasis on classroom experience. In general terms, the Ministry of Education and the Agency for Quality Education employ two instruments for this purpose: the "Evaluation of Specific and Pedagogical Knowledge" and the "Professional Portfolio of Pedagogical Competencies."

The career progression mechanism introduced by the SDPD organizes teachers into levels, which they can attain by demonstrating specific experience, competencies, and skills, along with their performance in various assessment moments (Ministerio de Educación, 2016).

The system establishes three phases of career progression:

- Phase 1 (Mandatory): Includes three levels—Initial, Early, and Advanced—intended to ensure that teachers reach the competencies required for effective teaching.

- Phase 2 (Voluntary): Includes two levels—Expert I and Expert II—for teachers who seek to further develop their professional skills.

- Phase 3 (Exceptional): Applies to teachers who lack records in the formal evaluation instruments, placing them temporarily in a transitional level called "Access."

The following table shows how teachers are categorized based on the results of assessment tools:

TABLE I: Category Assignment Based on Assessment Tools

| Portfolio Instrument | Evaluation Instrument | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| A | Expert II | Expert II | Expert I | Early |

| B | Expert II | Expert I | Advanced | Early |

| C | Expert I | Advanced | Early | Initial |

| D | Early | Early | Initial | Initial |

| E | Initial | |||

TABLE II: Salary Components for a Primary Teacher (44 hours/week and 30 years of service, i.e., 15 biennia). Values in Chilean pesos, 2021.

| Level | Component 1 (Experience) | Component 2 (Progression) | Component 3 (Fixed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access/Initial | $325.424 | $14.631 | $ - |

| Early | $48.214 | $ - | |

| Advanced | $97.036 | $100.713 | |

| Expert I | $363.779 | $139.879 | |

| Expert II | $782.867 | $212.616 |

Regarding training support, also contained in an amendment to the Teaching Statute made by Law 21,903, its ultimate goal is to generate the conditions for continuous improvement of the teaching function, focusing on on training for professional practice, and induction into professional practice.

Additionally, the resources allocated by the Chilean state to special allowances for education professionals increased by 76.13% (in nominal terms), between 2016 and 2018, from CLP 220.6 billion to CLP 388.5 billion (Dirección de Presupuesto, 2020).

The structural reforms introduced by Law No. 20,903 seek to redefine the teacher compensation system, offering a clear career path and salary trajectory for those who choose to dedicate their professional life to teaching. The ultimate goal is to attract talented individuals to the profession and, in turn, improve student learning outcomes.

Currently, the Teacher Career Path is fully implemented in the municipal sector, with gradual expansion into subsidized private education and pilot programs in early childhood education. The policy thus aims to become a cross-cutting reform throughout Chile´s primary and secondary education system.

Methodology and Data

Regardless of the instrument or tool used, public policies aim to improve the well-being of a target population through various mechanisms, such as monetary transfers, direct services, and other possible interventions (Gertler et al., 2017).

Undoubtedly, the public policies assessment is a valuable exercise that allows for corrections, redesigns, or even the elimination of policies that fail to achieve their intended objectives.

The need to assess the effects of policy instruments has given rise to policy evaluation, which seeks to determine both, the degree to fulfil goals and the efficiency of public resource use, considering their high opportunity cost. From a quantitative perspective, this process involves impact evaluation (Bernal Salazar & Peña, 2012).

Generally, impact evaluation aims to determine the extent to which a program causes changes in an outcome, defined as the variation between the effects on a treated group and those on a control group not exposed to the intervention:

The Difference-in-Differences (DiD) method evaluates changes in outcomes over time between individuals “treated” by a program and those who are not, forming the “control group” (Gertler et al., 2017).

One of the strengths of this method is its ability to control for unobservable individual characteristics that may influence the decision to participate in a program, as well as for exogenous factors such as socioeconomic and contextual variables (Dirección de Presupuesto, 2015).

This method is widely used in public policy and economics, allowing the evaluation of macro policies, school programs, wage changes, and more (Angrist & Pischke, 2015).

One of the earliest applications of the DiD approach was used to evaluate the effect of a minimum salary increase on unemployment in the fast-food industry in two U.S. states. The study concluded that the wage increase did not significantly affect unemployment (Card & Krueger, 1994).

From a formal standpoint, the DiD model can be expressed as:

This method allows estimation of the impact of the SDPD, under the assumption that test scores for the treated and control groups can be observed and compared over time. This condition is met in the current study, allowing for the identification of the average treatment effect, while acknowledging potential biases from unobserved time-varying variables.

The approach is quantitative, using multiple regression techniques to evaluate the effects of the SDPD on student outcomes in standardized tests—both language and mathematics—before and after policy implementation.

The unit of analysis consists of students who were in 4th grade in 2016 and in 6th grade in 2018, for whom SIMCE results, GPA, average attendance, and other relevant variables are available for both years.

Data Sources

This study uses secondary data from the Chilean Agency for Quality Education, covering students who took the SIMCE in 4th grade in 2016—before the SDPD implementation—and the same students’ performance in 6th grade in 2018—after the SDPD had been introduced. In forward, the 2016 period data is the “pre” and 2018 period is the “post” SDPD.

The datasets include information on student family background, such as socioeconomic status and mother’s educational attainment.

Additional datasets from the Ministry of Education provide information on teachers, student GPAs, and average attendance for both the pre- and post-policy periods.

TABLE III: Summary of Variables Used in the Study

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| SIMCE | Scores in the SIMCE Mathematics and Language assessments |

| GPA | Student’s general grade point average (pre and post) |

| Treated | Binary variable indicating whether the student’s teacher is part of the SDPD (0 = No, 1 = Yes). The student benefits from the policy when they teacher is treated, taking value 1, or 0 value in contrast. |

| Period | Indicates whether data is from before (2016 = 0) or after (2018 = 1) policy implementation |

| Attendance | Student’s average attendance percentage per period |

| Socioeconomic Group | Categorical variable from parent surveys, with 5 groups: 1 = Low, 2=Middel Low, 3=Middle, 4=Middle High, 5 = High |

| Mother´s Education | Continuous variable indicating the mother´s years of schooling |

| Vulnerability Index (IVE) | School’s vulnerability percentage, as determined by JUNAEB |

| Rurality | Binary variable for school location: 1 = Urban, 2 = Rural |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Treatment and Control Groups

The treatment group consists of students enrolled in public schools (Municipal, Municipal Corporations, or Local Public Education Services) whose administrative status remained unchanged between the two observation periods (“Before” and “After”). These schools and their teachers were required to participate in the SDPD, making both, the institutions and their students, part of the treated group.

To construct the control group, the full dataset from the Agency for Quality Education and the Ministry of Education was analysed.

First, to eliminate the effect of co-financed schools, only records from tuition-free institutions were retained. Establishments categorized as “Private Paid” and “Delegated Administration” were excluded, the latter being a special category of institutions managed directly by the Ministry of Education.

Next, only students who were present in both 2016 (“Before”) and 2018 (“After”), and whose schools maintained the same administrative dependency, were included. Additionally, only those with valid records for both SIMCE scores and GPA were available. The resulting groups, by time period, are shown in the table below:

TABLE IV: Students by Administrative Dependency and Period

| Dependency | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal Corporation | 6.100 | 6.100 |

| Municipal DAEM | 14.534 | 14.534 |

| Subsidized Private | 20.641 | 20.641 |

| 41.275 | 41.275 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

In terms of policy evaluation and data analysis, the treatment and control groups, by period, are defined as follows:

TABLE V: Treatment and Control Groups by Period

| Group | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 20.641 | 20.641 |

| Treated | 20.634 | 20.634 |

| 41.275 | 41.275 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

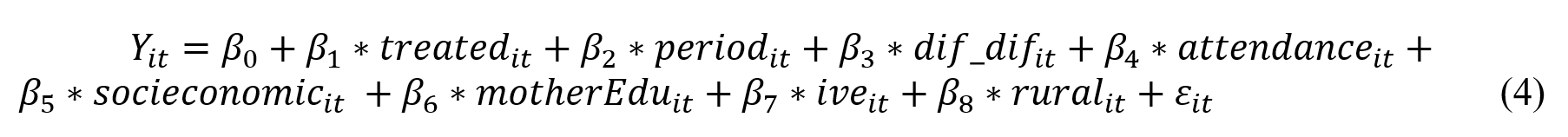

Model

The general model used to estimate the difference-in-differences (DiDcorresponds to a multiple linear regression. Its structure is as follows:

Where

The subscripts "i" and "t" represent the individual (student) and the period (before/after).

Results

Before reviewing the estimation results and the impact of the SDPD, it is important to analyse certain statistics that are relevant for understanding the characteristics of both, the treatment and control groups.

In general terms, the control group shows higher performance than the treatment group in standardized assessments, as well as in overall GPA, class attendance, and mother’s level of education. This reflects the documented performance gap between public and subsidized private schools in the Chilean education system.

TABLE VI: Means of Quantitative Variables

| Variable | Control Before | Control After | Treated Before | Treated After |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIMCE Math | 263,3 (45,2) |

250,9 (46,1) |

251,1 (46,5) |

236,7 (45,8) |

| SIMCE Language | 267,2 (48,6) |

250,6 (49,9) |

257,6 (50,9) |

240,5 (50,9) |

| GPA | 5,9 (0,48) |

5,7 (0,5) |

5,9 (0,5) |

5,8 (0,6) |

| Attendance | 93,8 (5,3) |

94,1 (5,4) |

93,4 (5,8) |

93,7 (5,9) |

| Mother´s Education | 11,7 (3,0) |

11,6 (3,1) |

10,6 (3,2) |

10,6 (3,3) |

| Observations | 20.641 | 20.641 | 20.634 | 20.634 |

| Std. Error | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,3 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Note: Standard deviations in parentheses.

The impact of the Teacher Professional Development System (SDPD) on student outcomes—measured by the SIMCE Mathematics and Language test scores—is estimated through four models. The first model includes the effect of being treated, the period, and their interaction.

The second model incorporates the effect of average class attendance. The third model includes the student’s socioeconomic status and the mother’s level of education. Finally, the fourth model introduces contextual variables such as the school’s vulnerability index (IVE) and rurality.

The first estimation for SIMCE Mathematics results shows a marginally negative impact of the policy with high statistical significance. When attendance is included (Model 2), the previous trend remains, and the expected effect of higher attendance—i.e., improved outcomes—is confirmed, with all estimators showing strong statistical significance.

In the third model, the coefficient for the difference-in-differences estimator becomes more negative than in previous models, though the magnitude remains marginal in the context of the test score scale. Furthermore, higher socioeconomic status is associated with better student performance, though in the highest segment, the coefficient is not statistically significant.

There is also evidence of a strong relationship between the mother’s educational level and the child’s likelihood of attending school regularly and performing better in standardized tests (Cui, Liu, & Zhah, 2019). Similar studies indicate that it is the mother’s, not the father’s, education that has the greatest influence on student outcomes (Hortcsu, 1995).

Finally, by including background variables—such as JUNAEB’ss IVE indicator and school rurality—the fourth model offers a more comprehensive view. As expected, the IVE variable shows a negative effect. Interestingly, rural schools show a counterintuitive positive effect compared to urban schools.

TABLE VII: Estimates – SIMCE Mathematics Results

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 263,3306*** (0,3196115) |

178,697*** (2,668533) |

139,283*** (3,007508) |

156,966*** (3,608073) |

| Treated | -12,26354*** (0,4520373) |

-11,8672*** (0,4494496) |

-4,957422*** (0,4882392) |

-5,252403*** (0,4899491) |

| Period | -12,43031*** (0,451999) |

-12,64424*** (.4492856) |

-11,35677*** (0,4696307) |

-11,66573*** (0,4707623) |

| Dif_dif | -1,942351*** (0,6392773) |

-1,999126*** (0,6353754) |

-2,579345*** (0,6654378) |

-2,357485*** (0,6652894) |

| Attendance | 0,9019055*** (0,0282353) |

0,9692924*** (0,0306588) |

0,958575*** (0,0307381) |

|

Socioeconomic Medum Low Medium Medio High High |

6,160798*** (0,5220984) 15,96809*** (0,5777593) 23,93403*** (1,048525) 32,33316 (19,98394) |

5,95842*** (0,5607943) 13,61195*** (0,7374739) 17,80722*** (1,359901) 19,6197 (20,03089) |

||

| Mother Education | 1,820013*** (0,0560768) |

1,806004*** (0,0561321) |

||

| IVE | -19,34385*** (2,183219) |

|||

Rural Rural |

3,394623*** (0,5111698) |

|||

| R2 | 0,0405 | 0,0522 | 0,0922 | 0,0937 |

| R2 Adjusted | 0,0404 | 0,0521 | 0,0921 | 0,0935 |

| Observations | 82.550 | 82.549 | 72.294 | 72.294 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Note: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses.

When SIMCE Language is used as the dependent variable, the trends are similar to those observed in Mathematics, as shown in the following table.

TABLE VIII: Estimates – SIMCE Language Results

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 267,2071*** (0,3529809) |

211,839*** (3,019708) |

177,8426*** (3,335187) |

186,8694*** (3,998814) |

| Treated | -9,5999477*** (0,4995565) |

-9,361044*** (0,4986785) |

-3,38929*** (0,5406021) |

-3,904194*** (0,5425049) |

| Period | -16,57308*** (0,4992028) |

-16,72604*** (0,4982228) |

-15,37963*** (0,5194969) |

-15,50905*** (.5207427) |

| Dif_dif | -0,5775009 (0,7068239) |

-0,6170514 (0,7053462) |

-1,716617** (0,7365471) |

-1,566848** (0,7363702) |

| Attendance | 0,5896119*** (0,0319372) |

0,6295742*** (0,033998) |

0,6044654*** (0,0340839) |

|

Socioeconomic Medum Low Medium Medio High High |

2,693206*** (0,5783851) 10,39939*** (0,6397369) 18,2853*** (1,161111) 34,1114 (22,01371) |

3,842015*** (0,6212097) 10,83046*** (,8163871) 16,84091*** (1,505133) 29,18807 (22,06568) |

||

| Mother Education | 1,967703*** (0,0621063) |

1,974446*** (,0621653) |

||

| IVE | -9,895658*** (2,415535) |

|||

Rural Rural |

5,814154*** (0,565819) |

|||

| R2 | 0,0366 | 0,0407 | 0,0695 | 0,0711 |

| R2 Adjusted | 0,0366 | 0,0406 | 0,0694 | 0,0709 |

| Observations | 80.448 | 80.447 | 71.605 | 71.605 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Note: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses.

Discussion and Conclusions

There is broad consensus regarding the crucial role teachers play in the learning processes of their students. A teacher’s performance can significantly influence student achievement.

Education systems have adopted several strategies to ensure the presence of high-performing teachers in schools. These include recruiting the best candidates, offering professional development and training, and implementing economic incentive systems tied to specific performance goals.

The review of international experiences suggests that economic incentive policies for teachers are widely used as mechanisms to improve student outcomes. Although the evidence is not entirely conclusive, it does indicate that this strategy can yield the expected results.

Following several years of debate, Chile implemented the Teacher Professional Development System (SDPD) in 2017. Among other measures, this policy introduced economic incentives for teachers, with the dual aim of improving student learning outcomes and recognizing the social value of the teaching profession, based on international evidence.

Using data from the Agency for Quality Education, the Ministry of Education, and the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships (JUNAEB), a panel dataset was constructed, including observations from before and after the policy was implemented. This allowed the identification of a treated group, whose teachers were part of the SDPD, and a control group whose teachers were not. After estimating various models, the results indicate a marginally negative or null effect of the policy on student outcomes in standardized tests—particularly for Mathematics. Regarding Language test results, similar trends were observed, though with lower intensity and varying levels of statistical significance.

In addition, the results continue to show achievement gaps across socioeconomic groups, a persistent feature of the Chilean education system—albeit one that has narrowed slightly in recent years (Centro de Estudios MINEDUC, 2013).

The temporal perspective of the policy is also relevant. The SDPD began implementation in 2017 on the public system, with impact measured through standardized assessments conducted in late 2018. That is, the post-treatment period corresponds to the academic year immediately following implementation (with 2016 as the pre-treatment year). This limited timeframe may not fully capture potential changes in teacher performance resulting from the new incentive structure—representing a limitation of this evaluation and the extent to which its findings can inform long-term policy decisions.

It is worth noting that extending the evaluation period was not feasible due to major disruptions in the education system: the 2019 social outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 significantly affected classroom delivery, assessment implementation, and student learning. Recently the education processes returned to some degree of normality, making it possible to conduct future evaluations with a longer policy implementation horizon.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study suggest the need for ongoing monitoring of the policy, particularly considering its potential impact and fiscal costs.

In this context, it is advisable to conduct follow-up assessments from different perspectives. Beyond future impact evaluations with a longer time horizon, it may also be useful to analyse the policy’s administrative and financial implementation.

Moreover, it is important to explore the design of incentive systems. One illustrative case is the United Kingdom’s early 2000s model, which offered temporary bonuses to public school teachers who improved their performance, with the possibility of renewing the incentive if improvements persisted or improve (Burgess & Ratto, 2003).

However, any incentive system must consider elements such as moral hazard (related to performance-based rewards) and pre-contract conditions (Fernández, 2005). Therefore, incentives should not focus solely on standardized test results. Recognizing the formative role of teachers in society, incentive structures should also encourage attention to school climate and the holistic development of students, which may involve factors not easily observed or measured.

As a recently implemented policy, the SDPD still requires substantial refinement and consolidation, and resources. In a virtuous cycle of public policy, it is essential to continue observing the system and to conduct new evaluations to identify corrective actions—ultimately turning the SDPD into a meaningful contribution to the quality of education for Chilean students.

Undoubtedly, the SDPD is still a young policy, which require further development in its implementation, extension and resource requirements. In a virtuous cycle of public policies, it should continue to be observed and evaluated in order to determine corrective actions to become an initiative that contributes to the quality of education for Chilean students.

Referencias bibliográficas

Acuña Ruz, F. (2015). Incentivos al trabajo profesional docente y

su relación con las políticas de evaluación e incentivo económico

individual.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2015).

Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). Cómo hicieron los sistemas

educativos con mejor desempeño del mundo para alcanzar sus objetivos.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-I-Martín, X. (2018).

Becker, G. (1993).

Bellés-Obrero, C., & Lombardi, M. (2022). Teacher Performance

Pay and Student Learning: Evidence from a Nationwide Program in Peru.

Bernal Salazar, R., & Peña, X. (2012).

Bravo, D., Flores, B., & Medrano, P. (2010). ¿Se premia la

habilidad en el mercado laboral docente?¿Cuánto impacta en el

desempeño de los estudiantes?

Bueno, C., & Saas, R. R. (2018). The Effects of Differential

Pay on Teacher Recruitment and Retention.

Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum Wages and

Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and

Pennsylvania.

CPEIP Ministerio de Educación. (2020).

Dirección de Presupuesto. (2015).

Dirección de Presupuesto. (2020).

Dixit, A. (2002). Incentives and Organizations in the Public

Sector: An Interpretative Review.

Eyzaguirre, S., & Ochoa, F. (2015). Fortalecimiento de la

Carrera Docente.

Fryer, R. G., Levitt, S. D., List, J., & Sadoff, S. (2018).

Enhancing the efficacy of teacher incentives through framing: A field

experiment.

Gertler, P. J., Martínez, S., Premand, P., Rawlings, L. B., &

Vermeersch, C. M. J. (2017).

Hanushek, E. A., Piopiunik, M., & Wiederhold, S. (2018). The

Value of Smarter Teachers: International Evidence on Teacher Cognitive

Skills and Student Performance.

Holmström, B. (1979). Moral Hazard and Observability.

Holmström, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask Principal–Agent

Analyses: Incentive Contracts, Asset Ownership, and Job Design.

Le-Foulon, C. (2000). Remuneraciones de los Profesores. Antedentes

para la discusión.

Leigh, A. (2012). Teacher pay and teacher aptitude.

Lépine, A. (2022). Teacher Incentives and Student Performance:

Evidence from Brazil.

Ministerio de Educación. (2016).

Rivera, C. (2018). Sistema de Desarrollo Profesional Docente. En

Rojas, P. (1998). Remuneraciones de los profesores en Chile.

Sala-I-Martín, X. (2019).

Información de contacto / Contact info: Felipe Monjes García. E-mail: felipemonjes@gmail.com