Contribution to knowledge in Educational Research through scale validation studies: a critical review on the work of M. Tourón et al. (2023) and the methodological analysis by Martínez-García (2024)

Contribución al conocimiento en Investigación Educativa a partir de estudios de validación de escalas: una reflexión crítica sobre el trabajo de M. Tourón et al. (2023) y el análisis metodológico de Martínez-García (2024)

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-406-637

Fernando Martínez Abad

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1783-8198

Universidad de Salamanca

José Carlos Sánchez Prieto

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8917-9814

Universidad de Salamanca

Abstract

In the scientific literature, there is a considerable volume of research proposing the design and validation of measurement scales in the field of educational sciences. This work presents, from the perspective of applied educational research, a critical analysis of the validation of the detection scale for high-ability students (GRS 2) for parents published by M. Tourón et al. (2023) in Revista de Educación, taking into account the methodological critique made by Martínez-García (2024) of said validation. The present proposal aims to contribute to this dialogue by analyzing both publications and formulating improvement issues, focusing especially on the theoretical foundation of the models, the formulation of reflective and formative compounds, and the adequacy of using alternative goodness-of-fit indicators to Chi Square in the confirmatory factor analysis model. Certain procedures deeply established in psychometric validation studies within educational research are observed, which, besides not promoting the understanding of the theoretical foundations underlying the scale, hinder its subsequent appropriate use by applied researchers in diagnostic or experimental studies. Thus, the analyzed arguments highlight the need to reconsider, in our view, some of the common practices in this type of studies that diminish their relevance and the implications of the results obtained for the development of educational theory and practice.

Keywords: scales validation, explanatory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, structural equations modelling, formative models.

Resumen

Existe en la literatura científica un gran volumen de investigaciones que proponen el diseño y validación de escalas de medida en el ámbito de las ciencias de la educación. Este trabajo presenta, desde el punto de vista de la investigación educativa aplicada, un análisis crítico de la validación de la escala de detección de alumnos con altas capacidades (GRS 2) para padres publicada por M. Tourón et al. (2023) en Revista de Educación, teniendo en cuenta la crítica metodológica realizada por Martínez-García (2024) a dicha validación. La presente propuesta pretende sumarse a este diálogo mediante el análisis de ambas publicaciones y la formulación de cuestiones de mejora, centrándose especialmente en la fundamentación teórica de los modelos, la formulación de compuestos reflectivos y formativos, y la adecuación del uso de indicadores de bondad de ajuste alternativos al Chi Cuadrado en el modelo de análisis factorial confirmatorio. Se observa la aplicación de ciertos procedimientos muy asentados en los estudios de validación psicométrica dentro de la investigación educativa que, además de no promover la comprensión de las bases teóricas en las que se fundamenta la escala, dificultan su adecuado empleo posterior por parte de investigadores aplicados en estudios diagnósticos o experimentales. Así, los argumentos analizados ponen de relieve la necesidad de replantear, a nuestro juicio, algunas de las prácticas habituales en este tipo de estudios que disminuyen su relevancia y las implicaciones de los resultados obtenidos para el desarrollo de la teoría y la práctica educativa.

Palabras clave: validación de escalas, análisis factorial exploratorio, análisis factorial confirmatorio, modelos de ecuaciones estructurales, modelos formativos.

Introduction

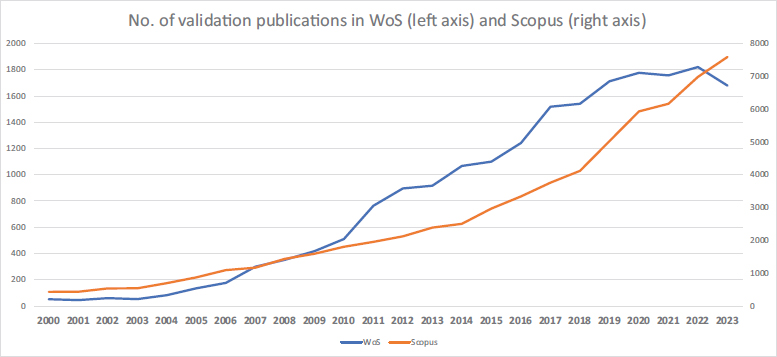

Psychometric studies for the design and validation of scales and instruments are a popular and profuse line of work in educational research with ample presence in scientific publications on social sciences and education, as shown in Figure I. Interest in the design and validation of measurement scales has in fact increased exponentially, with a significant rise in the number of scientific publications in both databases since 2005.

FIGURE I. Evolution of the number of scale validation publications in WoS and Scopus

NOTE: WoS search in Education & Educational Research area sources and Social Sciences area sources in Scopus. Search chain: (validation OR design OR psychometric) AND (scale OR instrument).

As proof, more and more journals are arguing this casuistry to justify rejecting proposals; some even include this in their author guidelines (e.g., Educación XX1, 2024).

A good example of this type of work is the study by M. Tourón et al. (2023) recently published in Revista de Educación. It addresses psychometric validation in the Spanish population of the Parent Gifted Rating Scale (GRS 2), including an initial exploration with an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and based on these prior results, the validation of eight different dimensional models proposed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to select the most appropriate model for the data.

The scale design and statistical validation process is potentially valuable for the scientific community since it means traits and constructs in a target population can be properly measured in applied studies, whether exploratory, correlational or experimental. Therefore, our perspective is that psychometric study results must clearly and systematically document all information for other educational researchers to take advantage of their potential.

In this context, and considering that Martínez-García’s critical analysis (2024) mainly centres on the methodological decisions taken by M. Tourón et al. (2023) in the statistical validation process, this review aims to contribute to the debate by focusing on how both the GRS 2 scale proposed by M. Tourón et al. (2023) and critiques by Martínez-García (2024) are a practical contribution for applied educational researchers.

This document is divided into four main sections. First, a reflection on how the study by M. Tourón et al. (2023) and Martínez-García’s critiques (2024) contribute to scientific development in the field of research science. The relevance of the methodological decisions made in the psychometric validation article are then analysed, focusing on whether these decisions contribute to a better understanding of the scale validated, promoting its use in applied studies and, finally, a development in knowledge of studies of gifted individuals. The third block centres on breaking down and discussing the main critiques presented by Martínez-García (2024), once again from a more practical-applied perspective than the theoretical-basic approach developed by the author in the critical analysis. Lastly, a conclusion reflecting on how the dubious practices identified here are widespread in educational research and the need for awareness about them that can lead to papers with an approach that does not focus mainly on publishability.

Contribution to scientific output in educational research

Firstly, we value the technical procedures and statistical decisions implemented by M. Tourón et al. (2023) very positively. Martínez-García (2024) highlights that the validation study makes a significant effort to develop a systematic procedure that follows the most common standards and customs in psychometric research. However, some important obstacles make it difficult to trace and apply the results obtained and presented.

Despite the GRS 2 scale being originally published in English and the items translated for the validation process, M. Tourón et al. (2023) notably do not present the full list of items translated. This omission makes it difficult to properly understand and follow the decisions made in relation to dimensional models tested in the paper, while making it impossible to use the scale in applied studies. Given that the original scale belongs to a publisher (MHS), it is most likely not possible to publish the complete scale as indirectly inferred by the authors when they refer to translating the items. At the very least, these types of practices are not the most suitable to contribute to advancing scientific knowledge, open science and developing future academic work.

On the other hand, despite the efforts of M. Tourón et al. (2023) to define all plausible dimensional models from a series of items and test their fit, the authors do not dedicate the same effort to justifying the relevance and theoretical meaning of each of the models validated.

Although the authors do include a theoretical reflection on the model finally selected in the conclusions, omitting a broader justification of all the models tested not only prevents the reader from better understanding the GRS 2 scale and its dimensional structure, but also significantly limits the scope of the study by reducing the analysis of the relationship between theory and praxis.

More discussion of the implications of the results for the conceptualisation of intelligence and the relationship between its different components would have been useful for the scientific community; dividing the three initial dimensions into four during the EFA, adding two secondary dimensions during the CFA, is particularly striking.

At this point, it is also worth remembering the risks associated with defining the dimensional structure of a scale based only on empirical data (Brown, 2015; MacCallum et al., 1992; Schmitt et al., 2018). We thus believe that there may be a bias due to overfitting in the CFA results.

In summary, the paper by M. Tourón et al. (2023) does not include the content of the GRS 2 scale items or a clear justification for the eight dimensional models validated in the CFA applied. These two shortcomings hinder the article’s hermeneutic task and prevent its reproducibility as the scale theoretical dimension modelling process is incomplete. With a good theoretical development, the article would have been more than a mere presentation of a valid and reliable tool for detecting gifted individuals, providing information of interest for understanding the components of intelligence.

Overall, these limitations are a barrier for other researchers and professionals in education to continue progressing in the detection and study of gifted students.

Procedure and methodological decisions

As previously indicated, after an initial exploration of the dimensional structure by EFA, M. Tourón et al. (2023) propose and verify the fit of eight different dimensional models in the CFA. Although they follow common procedure for this type of analysis, the paper does not clarify the connection between the results of the EFA and the models proposed in the CFA. Here we partially agree with Martínez-García’s (2024) critique on the use of EFA in the paper as it is not clear how the EFA contributes to the decisions taken in applying the CFA. We therefore consider that applying the EFA in this article is contingent: there is a solid prior theory on the factor structure of the scale and evidence obtained in the EFA does not lead to decisions on which model to test in the CFA.

Although this will be discussed later in more depth, we must say that we do not agree with Martínez-García’s (2024) criticism of the use of fit indices complementary to the chi-squared test. Just as effect size statistics are extremely valuable for the proper interpretation of bivariate hypothesis tests (Cohen, 1988; Grissom & Kim, 2011), absolute and incremental fit indicators complementary to chi-squared allow for a more fine-tuned and clear analysis of the level of similarity between the empirical model and null and saturated models.

As previously indicated, one of the main limitations of this type of study is the purely empirical nature of decision making. Regarding the models tested in the CFA, the authors include models with correlated errors considering the information provided by modification indices. This is not the most recommendable practice as it can lead to artificially overfitted models that are difficult to interpret in practice (MacCallum et al., 1992; Schmitt et al., 2018). Taking into account that the original scale is first validated in a similar population, another decision that raises doubts is the change in dimension for item 17 in some models. Given that the authors do not report the factor weights of the EFA models applied and the wording of the items is unknown, sufficient evidence is not provided to justify this decision.

A fundamental criticism by Martínez-García (2024) is related to the unjustified decision of M. Tourón et al. (2023) to consider the GRS 2 scale dimensions as reflective. The authors do not consider the possibility that the items, or the secondary construct tested in some models, could form a formative structure. We must take into account that the presence of dimensional formative structures in psychometric studies in educational science is residual. Hence it is important to divulge the characteristics and properties of formative structures in educational research in relation to the nature and assumptions of reflective factors.

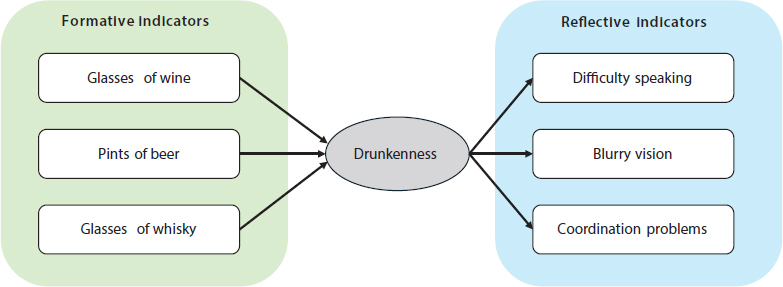

A reflective factor one in which latent variables are considered composites where the indicators are the result of that variable, so a change in the reflective composite causes a change in all indicators. On the other hand, in the case of formative factors, latent variables are considered composites in which the indicators are the cause so a change in the composite does not necessarily go hand-in-hand with a change in all indicators (Sarstedt et al., 2016). This difference in the composite-indicator relationship is represented graphically in the direction of the arrows connecting the composite with its indicators; in reflective composites, the arrows go from the composite to its indicators (as in CB-SEM models) while the arrows go in the other direction in formative composites.

A classic example of the difference between reflective and formative composites in the example of drunkenness (Figure II) (Chin, 1998). In this case, if we were to model drunkenness reflectively, the indicators would be “double vision”, “difficulty speaking” or “coordination problems”, such that an increase in drunkenness would increase its indicators. On the contrary, if drunkenness were a formative composite, it would include indicators such as “number of beers”, “number of glasses of wine” or “number of glasses of whisky”; in this case, increased drunkenness would not mean a rise in all indicators.

FIGURE II. Difference between reflective and formative indicators

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The question of using models that include formative composites is an open point of debate that intertwines with the dispute in the scientific community on the validity of composite confirmatory analysis (CCA), which is only possible by applying structural equation models based on partial least squares (PLS-SEM), a predictive-causal technique (Hair et al., 2011). This matter has implications that will be dealt with later.

Regarding the critique by Martínez-García (2024), it is difficult to ascertain if the scale validated by the authors includes reflective or formative composites as this is not addressed in the article and as previously mentioned, there is no complete list of items for the reader to judge for themselves. However, in our opinion, judging by some of the items mentioned and considering the theoretical structures proposed, at least some of the composites could be formative. In summary, although we do not agree with all of Martínez-García’s (2024) criticisms, the article by M. Tourón et al. (2023) could be considered to have some limitations stemming from a lack of justification of the models proposed, decision-making based on data that can cause bias due to overfitting and the use of reflective factors without prior consideration. These problems are not exclusive to the article discussed, rather they exemplify questions widely addressed in literature as a result of the automatic writing process of articles (according to Martínez-García (2024)) often used due to pressure to intensify the dissemination of outcomes (Martínez-García & Martínez-Caro, 2009).

Critical analysis of Martínez-García (2024)

As previously stated, one of the cornerstones of Martínez-García’s (2024) criticism of the work of M. Tourón et al. (2023) is that latent factors are predetermined as reflective in all the models defined without considering the possibility that they may be formative. Although we essentially agree with this criticism, it is important to note that Martínez-García’s (2024) argument is based only on statistical and mathematical issues, without demonstrating the formative nature of these factors based on the wording of their items. In fact, we believe that Martínez-García (2024) presents a reductionist vision of reflective models by stating that:

The observable indicators are reflective […] so each of these dimensions could be measured with just one indicator. If a researcher thinks that a single indicator is insufficient to measure a latent variable and more are needed because the latent variable is broad […], that battery of indicators is likely to be measuring different latent variables (Martínez-García, 2024)

We strongly disagree with this statement; from our perspective there are phenomena with a wide range of measurable responses and conducts that are expected to be correlated and together provide nuances and greater accuracy in factor measurement. To illustrate this matter, we need only remember the previous example of drunkenness in which possible manifestations are highly varied so, although they are correlated, not including all possible manifestations could be considered to reduce accuracy in measuring the factor.

Another key issue highlighted by Martínez-García (2024), briefly addressed above but that we would like to look at in more detail, refers to the use of absolute and incremental fit indices complementary to the chi-squared test. Martínez-García (2024) is categorical when he states that these indicators “are often used to fit the model so as to avoid the only test suitable for detecting poor model specification (the chi-squared test or, more specifically, the family of chi-squared tests)”. Adding that “when a model does not pass the chi-squared test, the estimated parameters cannot be interpreted as one or various covariance relationships implied by the model is not supported by empirical data, which immediately causes bias in estimates” (Martínez-García, 2024). We could accept this position if the chi-squared test were infallible but it is well known that this test returns inflated scores (leading to a very high model rejection rate) under conditions of lack of multivariate normality (e.g., Curran et al., 1996; Hu et al., 1992) or, as Martínez-García (2024) admits, it may fail to detect poorly specified models. In his discussion, Martínez-García (2024) also contrasts extensive existing literature by leading authors in this field, who “criticise the chi-squared test and recommend approximate fit indices”, with criticism of these indices by Hayduk (2014), a researcher with relative levels of dissemination and impact in the field of basic research on modelling with clearly inferior covariance structures1. At this point, we must ask whether the relative irrelevance of Hayduk compared to leading researchers like Jöreskog, Bentler, Steiger or Browne is because his work makes no significant contribution to knowledge, or because his discourse is inconvenient for the publishability of studies including structural equation models (SEM) and for the commercial exploitation of the main statistical packages to obtain them.

Finally, when examining Martínez-García’s (2024) criticisms as a whole, we can see that he does not consider the problem of studying fit levels of models with formative composites. As previously indicated, it is important to note that the definition of formative composites is not formally possible in traditional models based on covariance structures, or MEE. Formative factors can be theorised and validated using partial least square methods (PLS-SEM) based on data variance structures. Unlike covariance structure-based techniques, PLS-SEM is more flexible in terms of prior assumptions and fit to theoretical distributions. It is considered an exploratory and confirmatory technique that studies predictive-causal relationships (Hair et al., 2022). In fact, the chi-squared test cannot be used to verify the fit of PLS-SEM models. Moreover, despite current PLS-SEM tools allowing us to study model fit using approximate fit indicators (e.g., RMSEA, CFI, TLI), their use is not recommended by many leading researchers in the field (Hair et al., 2022). Add to this that, in the case of formative composites, other prior assumptions present in CFA, such as item load analysis, composite reliability index or average variance extracted, are not applied either.

In short, despite the critical analysis by Martínez-García (2024) advocating the use of the chi-squared test as the only valid evidence to verify good or bad model fit, while defending the existence of formative dimensions in the GRS-2 scale factor model, he does not offer solutions as to how to validate the fit of this model with formative dimensions without using approximate fit indicators.

Conclusions

With all its strengths and limitations, the study by M. Tourón et al. (2024) is a good example of how statistical scale validation processes are being designed and implemented in educational research. The problems addressed in our critical analysis are not specific to the proposals of M. Tourón et al. (2023) and Martínez-García (2024), they are issues widely observed in psychometric research in the field of education science.

Firstly, psychometric validation studies often do not document the full wording of items on the validated scales (e.g., Fumero & Miguel, 2023; Quijada et al., 2020). One of the main reasons, as appears to be the case of M. Tourón et al. (2023), are intellectual property rights applicable to the scales validated. Other studies are published in a different language to the scales applied in the pilot sample. In these cases, it is common for scale items to be published translated into the language of the journal and not the original language (e.g., Hernández Ramos et al., 2014; Quijada et al., 2020; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2019), creating potential bias and hindering their correct use. Although these practices are not recommended, they are so established in the field of social and education science that they are often not detected by editors, proofreaders or readers who are experts in the field, and scientists accept them as good practice. This is perfectly illustrated in the criticisms presented by Martínez-García (2024) who, in addition to not mentioning this omission, comments the formative nature of the dimensions without knowing how the items are worded.

Another important issue is developing an excessively empirical approach in statistical scale validation processes, largely ignoring the theoretical model used to build the original scale. This perspective based fundamentally on the search for the empirical model with the best fit can lead to solutions with little theoretical and practice sense. A good example of this are papers that compare the fit of several empirically plausible models without justifying their theoretical relevance (e.g., Rodríguez Conde et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2019); studies that include correlation parameters among the errors of some items based exclusively on the modification indices obtained (e.g., Thomas et al., 2019; J. Tourón et al., 2018); or research that exchanges items between the dimensions available —or even creates new dimensions— without considering the theoretical models and indicators used to design the scale (e.g., J. Tourón et al., 2018). Considering that M. Tourón et al. (2023) do not address this problem in their limitation analysis, and that Martínez-García (2024) focuses his criticism and only offers proposals in relation to the identification and fit of the models compared, our hypothesis is that educational researchers have assumed and accepted this method. So, we ask if it is necessary to redirect statistical validation studies in educational research: should we sacrifice goodness of fit in models (with the consequent reduction in publishability of our papers) in exchange for them being more coherent and explanatory of reality? In our opinion, we must foster this practice by integrating multidisciplinary teams in our scale design and validation processes, including experts in the constructs addressed and experts in psychometrics.

Although he does not go into greater depth, Martínez-García (2024) pinpoints automatic writing as a common problem in social sciences. Both the lack of in-depth statistical knowledge and taking an uncritical stance on the implications of the methodological procedures implemented can lead an educational researcher to search for ‘recipes’ and apply rigid protocols of action in scale validation. This leads towards a purely empiricist approach, far from the reflection needed on the theoretical and practical implications of the models studied. The effective contribution of these papers to educational development and improvement is limited in our opinion.

Regarding automatic writing —and largely due to pressure on academics to increase their scientific output—, salami slicing has become a widespread practice in recent years (Norman & Griffiths, 2008; Šupak Smolčić, 2013). This ethically dubious practice consists of separating, or breaking up, a unitary research project into various results reports, so that it possible to publish several different papers. Unfortunately, salami slicing has colonised all areas of scientific research and psychometric studies in educational research, such as the case analysed here, are no exception (M. Tourón et al., 2023, 2024).

Finally, we believe it is important to highlight the lack of awareness among educational researchers on the existence of formative factors as compared to the well-known reflective factors. This means that a reflective model is established by default in most cases to validate scales without first thinking about the most appropriate model. Given the problems associated with trying to validate formative factors as reflective (Hair et al., 2011), experts in the field must increase their efforts to disseminate this type of model and democratise their use in psychometric research.

In conclusion, debate on the article by M. Tourón et al. (2023) and subsequent criticism by Martínez-García (2024) gives us a chance to analyse a series of practices that have become internalised in psychometric studies in education that limit the development of the field. In our opinion, the overabundance of this type of study requires a leap in quality to increase their relevance and implications; a leap in quality that involves expanding the focus of researchers who are currently excessively focused on the almost mechanised reproduction of a series of methodological processes and complying with fit indices, relegating to the background the theoretical and practical implications of the fit models, which should be the main objective of this type of study.

Bibliographic references

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research (Second edition). Guilford Publications.

Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), vii–xvi.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2.ª ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Curran, P. J., West, S. G, & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16-29.

Educación XX1 (2024). Normas para la presentación de originales. https://revistas.uned.es/index.php/educacionXX1/libraryFiles/downloadPublic/170

Fumero, A., & Miguel, A. de. (2023). Validación de la versión española del NEO-FFI-30. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 49(179). https://doi.org/10.33776/amc.v49i179.7325

Grissom, R. J., & Kim, J. J. (2011). Effect sizes for research: Univariate and multivariate applications. Routledge Academic.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (3ª Ed.). Sage.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hayduk, L. A. (2014). Shame for disrespecting evidence: The personal consequences of insufficient respect for structural equation model testing. BMC: Medical Research Methodology, 14(124). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-124

Hernández Ramos, J. P., Martínez Abad, F., García Peñalvo, F. J., Herrera García, M. E., & Rodríguez Conde, M. J. (2014). Teachers’ attitude regarding the use of ICT. A factor reliability and validity study. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 509-516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.039

Hu, L., Bentler, P.M., & Kano, Y. (1992). Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 351-362.

MacCallum, R. C., Roznowski, M., & Necowitz, L. B. (1992). Model modifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychological Bulletin, 111(3), 490-504. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.490

Martínez-García, J.A. (2024, en prensa). Crítica del análisis de la validez de constructo de la Escala de Detección de alumnos con Altas Capacidades para Padres (GRS 2); réplica a Tourón et al. (2023). Revista de Educación.

Martínez-García, J. A., & Martínez-Caro, L. (2009). El análisis factorial confirmatorio y la validez de escalas en modelos causales. Anales de Psicología, 25(2), Article 2.

Norman, I., & Griffiths, P. (2008). Duplicate publication and «salami slicing»: Ethical issues and practical solutions. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(9), 1257-1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.07.003

Quijada, A., Ruiz, M. A., Huertas, J. A., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2020). Desarrollo y validación del Cuestionario de Clima Escolar para Profesores de Secundaria y Bachillerato (CES-PSB). Anales de Psicología, 36(1), 155-165. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.36.1.341001

Rodríguez Conde, M. J., Olmos Migueláñez, S., & Martínez Abad, F. (2012). Propiedades métricas y estructura dimensional de la adaptación española de una escala de evaluación de competencia informacional autopercibida (IL-HUMASS). Revista de investigación educativa, 30(2), 347-365.

Sánchez-Prieto, J. C., Hernández-García, Á., García-Peñalvo, F. J., Chaparro-Peláez, J., & Olmos-Migueláñez, S. (2019). Break the walls! Second-Order barriers and the acceptance of mLearning by first-year pre-service teachers. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.019

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 3998-4010 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.007

Schmitt, T. A., Sass, D. A., Chappelle, W., & Thompson, W. (2018). Selecting the “Best” Factor Structure and Moving Measurement Validation Forward: An Illustration. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(4), 345-362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1449116

Šupak Smolčić, V. (2013). Salami publication: Definitions and examples. Biochemia Medica, 23(3), 237-241. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2013.030

Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Coates, J. M., & Connor, J. P. (2019). Development and validation of the Bullying and Cyberbullying Scale for Adolescents: A multi-dimensional measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 75-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12223

Tourón, J., Martín, D., Navarro-Asencio, E., Pradas, S., & Iñigo, V. (2018). Validación de constructo de un instrumento para medir la competencia digital docente de los profesores (CDD). Revista española de pedagogía, 76(269), 25-54. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP76-1-2018-02

Tourón, M., Tourón, J., & Navarro-Asencio, E. (2023). Validez de Constructo de la Escala de Detección de Alumnado con Altas Capacidades para Profesores de Educación Infantil, Gifted Rating Scales (GRS2-P), en una muestra española. RELIEVE - Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 29(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v29i2.27787

Tourón, M., Tourón, J., & Navarro-Asencio, E. (2024). Validación española de la Escala de Detección de altas capacidades, «Gifted Rating Scales 2 (GRS 2-S) School Form», para profesores. Estudios sobre Educación, 46, 33-55. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.46.002

Contact address: Fernando Martínez Abad, Instituto Universitario de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Salamanca. Paseo Canalejas, 169. 37008, Salamanca. E-mail: fma@usal.es

_______________________________

1 In February 2024, Hayduk’s fundamental paper used as a basis by Martínez-García for his criticism (Hayduk, 2014) had a total of 44 citations in Google Scholar, 40 in Web of Science and 41 in Scopus.