The rural school in Spain in the 21st century: a systematic review following the PRISMA protocol

La escuela rural en España en el siglo XXI: una revisión sistemática según el protocolo PRISMA

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-407-666

Álvaro Moraleda-Ruano

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3638-8436

Universidad Camilo José Cela

Teresita Bernal-Romero

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5262-3312

Universidad Camilo José Cela

Abstract

This article presents a systematic review of scientific literature and book chapters addressing the situation of rural schools in Spain during the 21st century. It focuses on analyzing their current status, the challenges they face, and proposed strategies to improve rural education in the country. The method employed is based on the PRISMA protocol, with specific inclusion criteria for the rigorous selection of relevant studies and detailed data analysis. After reviewing a total of 863 publications, 20 were selected for an in-depth examination of rural education in Spain, highlighting the main challenges, identified opportunities, and relevant educational policies. Among the conclusions, the crucial role of rural schools as spaces for pedagogical innovation and community dynamization is emphasized, with significant socio-educational potential. The need to provide specific training for teachers working in rural settings is underscored, as well as the importance of establishing an updated legislative framework that strengthens their identity and resources. Priority is also given to addressing the digital divide and promoting technological integration in rural schools to ensure quality education in these contexts.

Keywords: rural school, rural education, systematic review, educational policy, Spain.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica y capítulos de libros que abordan la situación de la escuela rural en España durante el siglo XXI. Se enfoca en analizar su situación actual, los desafíos que enfrenta y las estrategias propuestas para mejorar la educación rural en el país. El método utilizado se fundamenta en el protocolo PRISMA, en criterios de inclusión específicos para la selección rigurosa de estudios relevantes y en un análisis detallado de datos. Tras revisar un total de 863 publicaciones, se seleccionaron 20 para examinar en profundidad la educación rural en España, destacando los principales desafíos, las oportunidades identificadas y las políticas educativas relevantes. Entre las conclusiones, resalta el papel crucial que desempeña la escuela rural como espacio de innovación pedagógica y dinamización comunitaria, con un gran potencial socioeducativo. Se insiste en la necesidad de proporcionar una formación específica para el profesorado que trabaja en entornos rurales y en la importancia de establecer un marco legislativo actualizado que fortalezca su identidad y recursos. Se destaca también la importancia de abordar de manera prioritaria la brecha digital y promover la integración tecnológica en las escuelas rurales para garantizar una educación de calidad en estos contextos.

Palabras clave: escuela rural, educación rural, revisión sistemática, política educativa, España.

Introduction

Education in rural Spain has faced continuous challenges since the nineteenth century due to educational policies that overlook the needs of rural schools and exacerbate their lack of recognition and support. There is a need to overcome economic, sociocultural and geographical obstacles which defy more urban centric perceptions (Corchón Álvarez et al., 2014). This systematic review aims to present a complete picture of the rural school in the twenty first century through explanations of the characteristic, challenges to and opportunities for this type of school (González et al., 2021).

Educational practice in rural schools is different to that in urban schools (Abós y Boix, 2017; Castro, 2018; Chaparro y Santos, 2018; García Prieto et al., 2021) with advantages such as the use of the environment as an educational resource and personalized attention to each pupil. (Álvarez y Vejo, 2017; Selusi y Sanahuja, 2020). Personalized attention and peer learning is key in rural schools (Ruiz y Ruiz-Gallardo, 2017). Yet, combining educational levels in one classroom requires efficient management of both time and resources (Uttech, 2003). Teachers design activities adapted to different age groups (Uttech, 2003) and foster interaction appropriate for each stage of development (Ruiz y Ruiz-Gallardo, 2017). Although there are fewer students than in urban schools, rural teachers often travel between different towns and villages, establishing a special connection with the rural environment to develop enriching educational experiences. (Hernández, 2000) that highlight the unique pedagogical importance of the rural school.

Rural schools are key agents in the fight against depopulation in rural Spain (Barba-Sánchez et al., 2021), not only for educational purposes in their regions but also to settle families in these areas, preserve regional identities and contribute to social cohesion. They are of special community and social value, carry out regulatory functioning and help reduce inequality. (Berlanga, 2003). For a relevant analysis of the situation of rural schools in twenty-first century Spain, we should delve into what they mean both pedagogically and at communitarian and social levels considering the legal framework built around them. From the Moyano Education Law in 1857 until the General Education Law of 1970, the model of the unitary classroom was installed up and down the country. This led to the concentration of schools in certain rural areas and the disappearance of those with less students (Santamaría, 2012). The organization for groups of rural schools (Colegios Rurales Agrupados (CRA) began in 1986 with the Spanish law (Real Decreto 2731/1986) to improve education management in rural areas. Spanish education laws like “LOGSE”, “LOE” and “LOMCE” refer to rural schools in several articles of law and the last few decades have seen an increase in references to quality of rural education (Santamaría, 2014). The most recent education law “LOMLOE” highlights the importance of rural schools and the need to train teachers and provide them with adequate resources.

Research on rural schools in Spain is scarce although researchers like Santamaría-Cárdaba y Sampedro (2020) have looked at characteristics and considered challenges. Carrete-Marín y Domingo-Peñafiel (2021) have studied technical resources in rural schools. Ferrando-Félix et al. (2019) explored the importance of physical education in rural schools and earlier research, like that of Feu (2004) y Álvarez-Álvarez et al. (2020) point out historical and contextual limitations in education in rural Spain. González et al. (2021) helped to analyze the role of the teacher and their relationships with the rural community.

To research this topic, we carried out a systematic review at three levels of analysis based on Bronfenbrenner´s Ecological Theory (1986), micro, meso and macrosystemic to describe the current situation and then analyze public policies in relation to rural schools in Spain. Our main objective is to carry out a systematic review of the research to date and assess the realities of the Spanish rural school in the twenty first century in two ways. First, by analyzing the academic research that targets the main challenges to education in a rural setting in the twenty first century and secondly, by analyzing research on policies, initiatives and proposals to improve education in the rural setting.

Method

Systematic Review Design

To carry out this systematic review, the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for systematic revision and metanalysis was used (Sánchez-Serrano et al., 2022; Page et al., 2021). Methodology was qualitative to systematically identifyand structure content taken from scientific publications.

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were established to guarantee updated literature relevance, appropriate in the context of rural education in Spain in the 21st century.

- Sources: Peer-reviewed scientific articles published in indexed scientific journals and academic book chapters, ensuring reliable information that stands up to rigorous assessment.

- Methodological design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods studies allowing for broad and deep understanding of rural education in Spain. Grey literature, systematic reviews and scientific articles that did not provide a detailed explanation of their research methodology were excluded.

- Date of Publication: Only those articles published after 2000 reflecting the current situation of rural education in the twenty first century, recent policies and new developments were included.

- Languages: Studies published in either Spanish or English for easier comprehension and analysis.

- Related terms: Studies must contain terms related to the semantic field of “the rural school”, guaranteeing total relevance for our study field in form and substance. Studies carried out in a rural schooling environment yet lacking information on the characteristics and particularities of rural schools were excluded since they focused on the theme of rural schooling as opposed to the specific context of rural schools.

- Spotlight on Spain: Studies should be centered on the characteristics and situation of rural education in a Spanish region to meet study objectives.

Search Strategies

This exhaustive search was carried out in academic data bases such as Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, Dialnet, Redalyc and Google Scholar, using a search strategy adapted to cover a wide range of relevant sources. The search equation used with Boolean operators was as follows: (“escuela rural” OR “instituciones educativas rurales” OR “enseñanza en zonas rurales” OR “rural education” OR “educación rural”) AND (“Spain” OR “España”) AND (“desafíos” OR “oportunidades” OR “challenges” OR “opportunities” OR “estrategias” OR “políticas” OR “strategies” OR “policies” OR “mejorar” OR “improving”).

Stages of the Systematic Review

The following review stages were developed using the same protocol: 1) Definition of the research problem, 2) Design of a protocol for the systematic review, 3) Shortlisting and selection of studies, 4) Information extraction, 5) Analysis and assessment. In the first phase, the field of study was defined focusing on the questions and objectives posed beforehand. The process involved the review of the relevant literature and an assessment of antecedents and contexts to establish a solid theoretical framework. This defining process established the base for the development of our methodology and posterior development of our study.

In the second phase dealing with the protocol design of the systematic review, we described the steps to take while searching for relevant literature, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the consulted databases, search equations and search strategies.

In the third phase, shortlisting and selection of studies, we proceeded to search for studies following the already established protocol. Articles with the same title were discarded or shortlisted based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process was carried out independently by both researchers to minimize bias and error. A review of the concordance and difference between both reviewers´ selected literature was later carried out to establish a final sample.

In the fourth phase, information extraction, a data extraction sheet was drawn up to register data, methodically and systematically collected from the included studies. The areas included on the sheet were, study title, authors, publication date, research methods and key findings.

In the fifth phase, analysis and assessment of the information, a detailed analysis of all registered data taken from studies included in the research was carried out. Tendencies, patterns and key findings were identified using Atlas.ti, version 23, as working software to organize and analyze the information. During this phase, a critical assessment of analyzed data and constant review of the categorization and recategorization process were carried out. Finally, all this information was set down in the scientific article.

Results

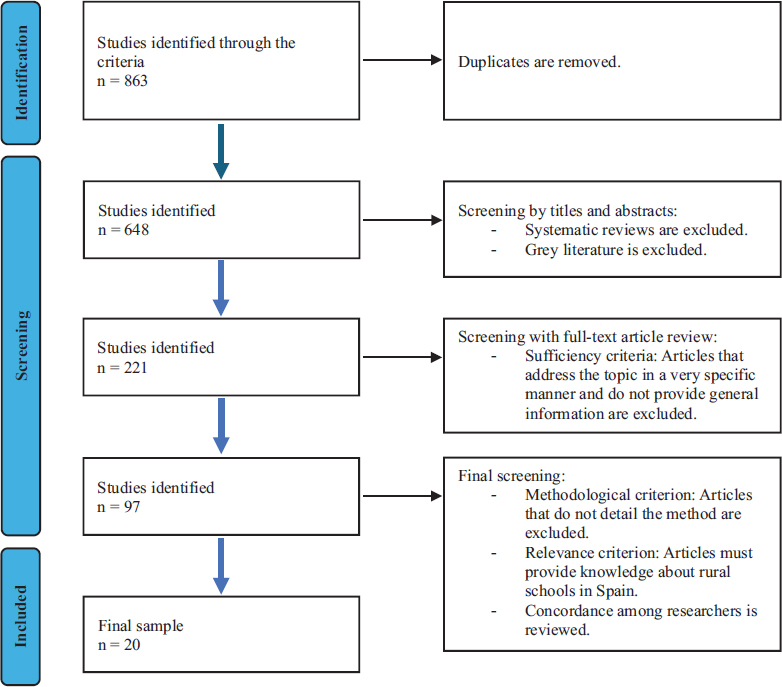

We compiled 863 publications from diverse data bases during the initial phase of research. Duplicates were eliminated leaving a total of 648 publications This selection was carried out in two stages, first a shortlist based on titles and abstracts and the second, after an analysis of the complete text. We found 97 studies that met our research criteriawhich we analyzed in detail. 20 studies out of those 97 were selected for the systematic review. Figure I shows results for the basis of the systematic review comprising relevant quality studies specifically targeting the situation of rural education In Spain in the 21st century and the challenges, opportunities, strategies and policies involved.

FIGURE I. PRISMA flow diagram for article selection

Source: Own elaboration.

General characteristics of selected studies

The final sample included 20 articles published between 2014 and 2022 (see Table I). 18 studies were written in Spanish and 2 in English, most of which aimed to describe, know or analyze the diverse variables linked with the rural school such as, the current situation, teacher training and satisfaction, the use of information and communication technologies (ICT), the use of textbooks, PISA results, students´ interests, inclusion exclusion processes and innovation. Only one of the article objectives was linked to investigative action. Most of the 20 studies employed quantitative methods (10), followed by qualitative methods (6) and finally, mixed methods (4). The most common data sources came from the teachers themselves because from their position as teachers, they have access to data relevant to the study perspectives. Students, directors, advisors and parents were sources least consulted in the studies analyzed. Although the important role of the rural schools in each region was identified, no members of the rural community were interviewed in the articles. Finally, the main conclusions present relevant data on rural schools and will be analyzed in detail during code analysis.

TABLE I. Characteristics of the studies analyzed

|

Publication Date and Language |

Title |

Objective |

Methods and sample |

1 |

2014/Spanish |

Integration of Information and Communication Technologies: An Evaluative Study on rural schools in Andalucia (Spain) |

To analyze the role of the teacher in Andalucia and identify initial teacher training to work with ICT in the classroom |

Quantitative Descriptive Teachers |

2 |

2015/Spanish |

Integration and Teacher Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in rural schools in Granada: A Descriptive Study |

To know ICT resources available to teachers in rural schools in the province of Granada and how teachers use these resources (frequency, type) outside the classroom |

Quantitative Exploratory Descriptive Teachers |

3 |

2015/Spanish |

Investigative Action: Professional Development for Physical Education Teachers in Rural Schools |

To analyze the impact of a working group for investigative action on the professional development of physical education teachers in rural schools |

Qualitative Multicase study Teachers |

4 |

2017/Spanish |

Analysis of Teacher Satisfaction in Rural Schools in the Province of Granada (Spain): Personal and Professional Relationships with the Education Community |

To assess the satisfaction level of teachers in rural schools in Granada province, their social and professional relationships with the education community of their schools |

Quantitative Teachers |

5 |

2017/Spanish |

How are Spanish Schools in the Rural Environment Situated in terms of Innovation? An Exploratory Study through Interviews |

To answer the question about the situation of schools in the rural environment in terms of innovation |

Qualitative Exploratory Teachers Directorate |

6 |

2017/Spanish |

Expectations and Beliefs of Students in Rural Education in terms of their academic and professional future |

To discover the expectations and beliefs of students in rural education in terms of their academic and professional future |

Quantitative Ex post facto Explicative Correlational Students |

7 |

2017/English |

The Spanish Rural School from the New Rural Paradigm. Evolution and Challenges for the Future |

To reflect and gain deeper insights on the context of rural schools |

Qualitative case studies Teachers Parents Directorate |

8 |

2017/Spanish |

Teacher Satisfaction with School Organization in Rural Schools in Granada Province (Spain) |

To know the organization of rural schools that pleases or displeases the teachers involved |

Quantitative Descriptive Teachers |

9 |

2017/Spanish |

The Use of Textbooks in Rural Education in Spain |

To understand the current role of textbooks and other school materials in rural schools |

Quantitative Descriptive Teachers |

10 |

2018/Spain |

The Global Competence of the Rural School in PISA 2018 |

To highlight the potential of PISA tests as a tool to understand educational conditions and results in rural areas |

Quantitative analysis of PISA report data |

11 |

2018/Spanish |

Reflections on the Rural School: A Successful Education Model |

To analyze current rural schools in Catalonia |

Mixed method design Teachers Parents Students |

12 |

2020/Spanish |

School Closures in Vulnerable Contexts from an Advisor Perspective: Impact on Rural Areas |

To understand how school advisors in rural areas perceive the impact of Covid-19 on teaching-learning processes |

Qualitative School Advisors |

13 |

2020/Spanish |

The Value of Place in Relations of Inclusion and Exclusion in a Grouped Rural School: An Ethnographic Study |

To identify the experiences of inclusion or exclusion among the members of a grouped rural school |

Qualitative Ethnographic Teachers Students Families |

14 |

2020/Spanish |

Environment, Educational Centres and Community Rural Schools in the North (Cantabria) and South of Spain (Huelva) |

To identify the similarities and differences in rural schools in the north and south of Spain |

Mixed method Teachers Directors |

15 |

2020 /Spanish |

The Rural School and External Evaluation in Spain: PISA as an Example |

To present data on the rural factor in Spain and in the OECD obtained from PISA publications |

Quantitative analysis of PISA report data |

16 |

2021/Spanish |

The Rural School: A Sought-after Teaching Post? |

To analyze the willingness of student teachers and qualified working primary school teachers from the Cantabria Region to take up teaching posts in the rural schools of their region |

Mixed method Teachers Students |

17 |

2021/Spanish |

Are Teaching Dynamics of Rural Schools in the North of Spain Different to those in the South of Spain? Tendencies, Contrasts and Similarities |

To know the current situation of the diverse types and singularities in rural educational centres in both the north and south of Spain |

Mixed method Teachers |

18 |

2022/English |

School in and Linked to Rural Territory: Teaching Practices in Connection with the Context from an Ethnographic Study |

To identify those educational practices taking place in context |

Qualitative Ethnographic Teachers Students Families |

19 |

2022/Spanish |

STEM/STEAM Interest in Secondary Education Students in Rural and Urban Areas in Spain |

To identify compulsory secondary education students‘inclinations towards specific areas of future knowledge regardless of academic performance |

Quantitative Students |

20 |

2022/Spanish |

Teacher Satisfaction with State-run Rural Schools in Granada Province in terms of their Professional Development |

To know the satisfaction levels of teachers from state-run rural schools in Granada province in terms of self-fulfillment and professional growth |

Qualitative Descriptive Teachers |

Source: Own elaboration.

Results by category and code

Through an in-depth analysis of the articles using both open and axial categorization considering the central category, reality of the rural school, we generated codes for the 4 initial categories: 1) current situation of Spanish rural schools, 2) challenges to rural schools, 3) opportunities for rural schools and 4) policies, initiatives and proposals for improvement. We then calculated the frequency of citations for each of the codes (see Table II). The total number of citations came to 624 and those with the greatest number of citations were as follows: lack of training and short teaching stays (68), the current rural school (64) and the visible school (61).

TABLE II. Frequency of citations by code

CATEGORIES |

CODES |

NUMBER OF CITATIONS |

1. Current Situation of the Spanish Rural School |

1.1. Rurality in the twenty-first century |

29 |

1.2. Rural schools today |

64 |

|

1.3. Validity of rural schools |

24 |

|

2. Challenges |

2.1. Lack of resources |

36 |

2.2. Lack of training and short-stay teachers |

68 |

|

2.3. Lack of students |

17 |

|

2.4. Curriculum and teaching programme adjustment |

25 |

|

2.5. Isolation and geographical dispersion |

24 |

|

2.6. Dualisms: global/local, traditional /innovation, rural/urban |

45 |

|

2.7. The invisible school |

29 |

|

3. Opportunities |

3.1. Openess to innovation |

34 |

3.2. Technologies |

17 |

|

3.3. Statements from international organisms |

13 |

|

4. Policies, Initiatives and Proposals |

4.1. Administration policies and initiatives |

39 |

4.2. Community, family and school |

59 |

|

4.3. The visible school |

61 |

|

4.4. Improvement Proposals |

40 |

Source: Own elaboration.

The Current Situation of the Spanish Rural School

In twenty first century rurality, concern about the possible extinction of the rural school due to depopulation caused by migratory flow towards cities persists (Tamargo et al., 2022). However, some authors like Álvarez-Álvarez et al. (2020), Morales-Romo (2017) y Santamaria (2020), describe a new, heterogeneous rurality. There has been a change from agrarian economies to economies based on tourism, leisure and second homes, causing temporary forms of settling (Álvarez-Álvarez, 2020; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; García et al., 2017; Morales-Romo, 2017). Rural areas are seeing the influence of new technologies, visibility of women, changes in communication and transportation systems and a certain hybridization process of the rural and the urban (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; Morales-Romo, 2017).

Rural schools today are presented in diverse ways, which makes categorization difficult (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020; García-Prieto et al., 2017; Lorenzo et al., 2017; Monge et al., 2020). Some authors prefer to refer to them as “schools in rural environments” (Bustos, 2007; Martínez y Bustos, 2011; García, 2015, cited in Álvarez-Álvarez y Gómez-Cobo, 2021). Diverse forms of organization like Grouped Rural Schools (CRA), State-run Rural Schools (CPR), Early Learning and Primary Schools (CEIP), Rural Schools for Educational Innovation (CRIES) and multigrade classrooms that vary depending on the context, have all been identified (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; García Prieto et al., 2021; Matías Solanilla y Vigo Arrazola, 2020; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015; Raso et al., 2015; Raso et al., 2017). Among these characteristics, cultural diversity due to repopulation processes is currently highlighted (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; García et al., 2017; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022). The use of textbooks and information technologies is increasing (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Raso et al., 2015), as is investment in more modern infrastructure (Raso et al., 2014; Tahull y Montero, 2018).

The validity of the rural school is evident with its flexibility and adaptability, making it essential for students and communities alike (Manzano y Tomé, 2016 cited in Lorenzo et al., 2017). It contributes notably to keeping rural territories active (Morales-Romo, 2017). Families are placing ever increasing value on the rural school, thus avoiding migration to urban areas in search of a higher quality education (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017).

Challenges

The lack of resources describes the lack of educational material or material adapted to a rural environment. Difficulties in accessing the internet in certain rural areas and deficiencies in infrastructure and installations are also mentioned (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; García et al., 2021, Pedraza-González et al., 2015; Monge et al., 2020; Raso et al., 2015; Raso, et al., 2022).

The lack of specific training and the problem of short stay teachers are key challenges to rural schools (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Morales-Romo, 2017; Raso et al., 2014). Teachers coming to this environment often know very little about the rural world, suitable teaching methods or information technologies (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021). They are recommended to acquire competences in the fields of Sociology and Psychology (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021). Even those teachers who do have experience in a rural environment often lack adequate ICT training (Raso et al., 2014). This lack of experience is common to both teachers and directors, who have usually worked in urban environments beforehand (González et al., 2021; Monge et al., 2020; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015; Raso et al., 2015). Job dissatisfaction and this lack of experience and training turn rural schools into centres for short term teaching posts with a constant coming and going of staff (Raso et al., 2015).

The lack of students is another worry since the existence of schools depends on the number of students. Such reduced numbers, multigrade classrooms and unitary classrooms bring challenges for designing, working with and evaluating several grades at the same time. Yet, it is important to mention that working with a reduced number of students fosters innovation and allows for attention to diversity (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015; Matías Solanilla y Vigo Arrazola, 2020, Morales-Romo, 2017; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022). The scarcity of students has caused administrations to consider how much they invest and thereby increase student ratios by grouping schools together (Morales-Romo, 2017).

How the curriculum, content and teaching programmes are adequately adjusted is another key challenge. Firstly, because the content is not related to the context (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; García et al., 2021; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015) and secondly, all the necessary teaching programmes are developed by one teacher, which complicates their workload.

Isolation and geographical dispersion pose the challenge of the distances between certain areas Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; Lorenzo, et al., 2017; Morales-Romo, 2017; Monge et al., 2020). This makes student socialization processes with other children from other towns and villages impossible. It is also an impediment for access to culture and different recreational activities, (Monge et al., 2020; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Raso et al., 2015) generating professional isolation (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015). This isolation leads to exhaustion in the itinerant teachers since they must travel between schools (Morales-Romo, 2017).

The rural school is confronted with dualisms that define their identity and future. They must opt between keeping their traditional rural identity or adopting more urban characteristics (Monge et al., 2020). The grouping strategy is another cause for dilemma since it may cause the invisibilization or even the disappearance of certain particularities in the different contexts (Santamaria, 2020). Educational reflections are centred on preserving local identity as opposed to adapting to any other context (García et al., 2017; Lorenzo et al., 2017; Raso et al., 2014; Tamargo et al., 2022). Students face the uncertainty of working in the rural environment or migrating, given the limitations for economic activity (Lorenzo et al., 2017). The technological divide is another challenge since access to the internet is limited which impedes the use of computers (Raso et al., 2014). Educational quality is also measured in the same parameters as for urban schools, reinforcing a more metrocentric vision, which limits rural development (García et al., 2017; Lorenzo et al., 2017; Morales-Romo, 2017; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022).

The rural school has been invisibilized by urban schools as shown in PISA (2015) reports or in legislation where it is barely mentioned (Morales-Romo, 2017; Pedraza-González et al., 2015; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Santamaria, 2020). The rural school “is plunged into the shade” (Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015, p.5). This invisibilization becomes more tangible when the administration gives greater support to urban schools through investment and public policy (Morales-Romo, 2017). They even seem to be forgotten by academia since there is very little research on the topic (Monge et al., 2020) and, in some cases, they seem to be disadvantaged because of where they are situated in the Spanish territory (Moreno-Pinillos, 2022).

Opportunities

The rural school´s openness to innovation with teachers intent on creating collaborative actions to facilitate learning (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; García et al., 2021; Morales-Romo, 2017; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015; Raso et al., 2014; Raso et al., 2015) must be highlighted. This innovation goes from teacher training to the use of technologies to overcome isolation or promote relationships in the environment Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; García et al., 2021). The idea that these innovations may first arise in the rural school is also considered since teachers take advantage of the small numbers of students to propose less conventional ideas (García et al., 2021). Along the same lines, the arrival of new technologies provides a valuable opportunity to access and create didactic resources, bring communities from other territories together and discover other realities (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Raso et al., 2015).

Finally, it is important to point out the declarations made by international organisms on the importance of the rural school. For example, UNESCO, the EU territorial Agenda 2020 or The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) have pointed out the importance of maintaining the rural contexts as “guardians of the territory” (Santamaria, 2018, p.6). Over the last 20 years, Spanish rural areas have received funding from the European programmes (LEADER2 y PRODER3) (Morales-Romo, 2017).

Policies, Iniciatives and Proposals

Regional administrations have implemented improvement proposals to improve aspects of rural schools. For example, Las Directrices Generales de la Estrategia Nacional frente al Reto Demográfico (General Guidelines of the National Strategy for Demographic Challenge) have suggested contemplating the demographic impact in all their laws (CGRD, 2019, p. 42, cited in Santamaría, 2018). El Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado (National Institute for Educational Technologies and Teacher Training) offers teacher training programmes and the Centres for Educational Innovation ((CRIes) provide experiences such as cinema, bilingualism and robotics (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015). Initiatives to integrate ICT into rural schools such as El Plan Andaluz de Introducción a las Nuevas Tecnologías de la Imagen y la Comunicación (PAINTIC) (Andalucia Plan for the Introduction of New Image and Communication Technologies) have been promoted along with the programmes REDAULA y AUL@BUS, and the creation of different ICT centres (Raso et al., 2015, p.3).

Itinerant teachers may also obtain benefits such as reduction of teaching or complementary hours and some councils provide economic incentives to teachers living in these rural areas (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021). A solid policy from the Education and Technical Training Ministry is necessary to provide the required specialist training for these teachers.

The school-family-community relationship is still crucial (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017), with strong commitment from the families (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; Morales-Romo, 2017) and emphasis on direct contact and collaboration in difficult situations (García et al.,2017; Matías Solanilla y Vigo Arrazola, 2020; Monge et al., 2020; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Raso Sánchez et al., 2017). Teachers have proposed measures like including parent representation in coexistence commissions (Matías Solanilla y Vigo Arrazola, 2020; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Tahull y Montero, 2018). The community also plays a significant role by integrating local culture into the school through collaborative projects (Morales-Romo, 2017) and collaborations with different entities (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017; Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Pedraza-González y López Pastor, 2015; Santamaria, 2020). Collaborative work is also fostered among teachers with groups for professional updating and the creation of networks of rural schools at state level (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017). To integrate local culture into the curriculum, initiatives like “Comunidades de Aprendizaje” (Learning Communities) and “Trabajo por Proyectos” (Working Projects) (Moreno-Pinillos, 2022; Morales-Romo, 2017) are highlighted.

Improvement Proposals emphasize the need to investigate in collaboration with educational institutions and to convert the rural schools into “centres for research” (Moreno-Pinillos, 2022). The importance of policies and economic resources (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; Raso Sánchez y Santana Aranda, 2022) has been underlined as well as the creation of networks between different regions to promote collaboration among education centres (Moreno-Pinillos, 2022). The importance of maintaining rural identity as part of the curriculum and develop didactic material to that end is highlighted (García et al., 2021; Santamaria, 2018), as is training of teachers in rural themes and technology (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021). Reflections are made on the necessity to reinforce processes of project exchange between rural and urban schools (Santamaría, 2018) while calling for greater participation in subsidized projects (Álvarez-Álvarez y Vejo-Sainz, 2017).

Finally, we highlight the rural school as a visible model in different areas. These schools can be examples of curricular adaptation, methodological innovation and management of student diversity, as well as collaboration with the community, families and other professionals (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2021; García et al., 2021; Santamaría, 2018; Tahull y Montero, 2018). Interactions among students of different age groups, teacher initiatives and collaborative work leads to closer relationships, strengthens autonomy and fosters solidarity, which contributes to higher education levels and effective curricular adjustments (Tahull y Montero, 2018). These achievements can be observed in areas which urban schools are still exploring how to approach.

Conclusions

Considerations on the potential of urban schools are promoted by voices in educational centres, institutions and universities (Boix, 2004). Although they undergo the same economic and symbolic marginality as the rural environment itself, the rural school stands out as a space for pedagogical innovation (Beach y Vigo-Arrazola, 2018) and as a dynamic force behind rural communities (Santamaría-Cárdaba y Sampedro, 2020).

Despite some isolated cases of specialist teacher training in rural education (Villalustre y Del Moral, 2011), it is essential to include subjects dealing with the rural context to the teacher training curriculum. Training rural teachers is crucial (Santamaría-Cárdaba y Sampedro, 2020), yet university training on education in rural schools is perceived as scarce and insufficient (Ruiz y Ruiz-Gallardo, 2017).

In the study by Monge et al. (2022), where 2224 study guides from the university degrees of Early Teaching and Primary Teaching in Spain were analyzed, it was revealed that university teacher training did not guarantee the necessary competences for working in rural schools. This indicates the sparse attention given to this context in teacher training programmes (Moreno, 2020). The rural school is notably absent in the list of educational competences that a teacher should achieve during teacher training since few related subjects are taught. (Anzano et al., 2022). Training in rural education is essential and urgently needs to be included in teacher training programmes as seen in some pioneering universities.

In the context of the rural school diverse conceptions based on “hypothesis” and “false beliefs”, lacking rigorous analysis through reflexive and critical training, can be observed (Abós, 2011). These beliefs may even affect the pupils, reporting lower interest levels and academic expectations in young people in rural areas than in urban areas (Tamargo et al., 2022). A current general framework on the legislation and rural educational models should be established, ensuring a socio-territorial voice backed by training models, post assignation and incentives suitable for rural teaching staff (Lorenzo et al., 2021).

The issue of the rural school transcends the lack of specific training for teaching staff. It must also deal with new inexperienced short-term teachers who have no sense of belonging. This threatens the identity of these institutions (Heredero et al., 2014). The lack of resources, means, material, infrastructure, short-staffed schools and the lack of legislation makes teaching in these schools a tough challenge.

Not only is adequate training important but a sense of commitment and belonging is also key since settling teachers in rural schools in Spain is crucial for maintaining close relationships and collaboration among educators and local communities (Rothenburger, 2015).

The scarcity of literature available on rural education in the Spanish educational context becomes very evident when compared to research in areas like ICT, basic competences or coexistence in educational centres (Bustos Jiménez, 2011).

The rural school in Spain faces challenges due to the constant changes in educational legislation influenced by the different political parties down through the years of democracy in the country. The intervention of some political parties and trade unions in support of rural education (Feu, 2004) as well as the need for political stability and an all-encompassing “Pacto de Estado” (State Pact) (Boix y Domingo-Peñafiel, 2015) is essential.

The rural school has great potential, especially as an organization that can optimize limited resources and allow for more coordinated working environments (González et al., 2021). Currently, lifestyles and customs in the rural school are undergoing gradual urbanization (Bustos Jiménez, 2009).

The digital divide worries the directorate (Del Moral et al., 2023). It is necessary to push forward with the transformation of classrooms by integrating technology (Fardoun et al., 2014), and new learning environments that provide resources to enhance educational achievement in rural settings (Carrete-Marín y Domingo-Peñafiel, 2023). We must develop new ways to facilitate multigrade learning and promote digital competence with the unique characteristics of the rural school in mind. We recommend setting up teacher support networks to foster effective resource exchange and continuous training in new technologies to push educational innovation forward (Carrete-Marín y Domingo-Peñafiel, 2021). This can already be seen with the advent of Artificial Intelligence, which may be either a valuable teacher tool or a source of conflict due to lack of adequate training, dependence on connectivity to the internet, the need to adapt it to rural characteristics and human intervention (Montiel-Ruiz y López, 2023).

Limitations

This research focuses on rural schools in Spain after 2000. There are limitations to the study in relation to the sample of analyzed articles. We have observed, in quite a few cases, that emphasis is placed more on the study theme than on the rural context itself. For example, several studies concentrate on didactic aspects but omit relevant data on school life in rural environments. We have also found studies describing very specific local contexts, which makes it difficult to extrapolate the results to a national level. For this reason, we excluded those studies with results that could not be generalized, maintaining those contributing to the study of the rural school as a whole.

Prospective

We have looked at different proposals that we will now summarize. It is essential to work on comprehensive support policies for the rural school, not only to repopulate “España vaciada” (Abandoned Spain) but also to promote identity and give visibility to these institutions. Teacher training programmes based on successful experiences of rurality in a proper rural context, as opposed to a more urban context. must be prioritized.

It is necessary to continue with this line of effective research involving systematic review on didactics and strategies which can bring current innovations in the field to light. However, it is also essential to transcend descriptive or correlational studies and start to design research using methods like the systemization of experiences and participatory action research. The former generates knowledge through practice, which would allow rural schools to show how they, themselves, understand the rural school and to share useful strategies with urban institutions. The latter allows for transformation and change in response to the needs of the context. Both research methods guarantee the effective transfer of knowledge along with the practical applications of said knowledge inside the study field.

Funding

This article is part of the research project titled “New Socio-Educational Approaches to Rural Schools in Spain” (NESERE). It has been funded by the IX Research Call of the University Camilo José Cela.

References

Abós, P. (2011). The rural school as a topic in the study plans for early childhood and primary pre-service teacher training in Spain. Profesorado, Revista De Currículum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 15(2), 39–52. https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/20255

Abós, P. y Boix, R. (2017). Evaluación de los aprendizajes en escuelas rurales multigrado. Aula Abierta, 45, 41-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.17811/rifie.45.2017.41-48

Álvarez Álvarez, C., García-Prieto, F. J., & Pozuelos-Estrada, F. J. (2020). Entorno, centros y comunidad de escuelas rurales del norte (Cantabria) y sur de España (Huelva). Contextos Educativos. Revista de Educación, 26, 177–196. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.4564

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., García Prieto, F., & Pozuelos Estrada, F. (2020). Posibilidades, limitaciones y demandas de los centros educativos del medio rural en el norte y sur de España contemplados desde la dirección escolar. Perfiles Educativos, 42(168), 94-106. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2020.168.59153

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., & Gómez-Cobo, P. (2021). La Escuela Rural: ¿un destino deseado por los docentes? Revista Interuniversitaria De Formación Del Profesorado. Continuación De La Antigua Revista De Escuelas Normales, 96(35.2). https://doi.org/10.47553/rifop.v97i35.2.81507

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., & Vejo-Sainz, R. (2017). ¿Cómo se sitúan las escuelas españolas del medio rural ante la innovación? Un estudio exploratorio mediante entrevistas. Aula Abierta, 45(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.45.1.2017.25-32

Anzano, S., Vázquez, S. y Liesa, M. (2022). Invisibilidad de la escuela rural en la formación de profesores. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 24, e27, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2022.24.e27.3974

Barba-Sánchez, V., Calderón, B, Calderón, M. J. & Sebastián, G. (2021). Aproximación al valor social de un colegio rural agrupado: el caso del CRA Sierra de Alcaraz, CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 101, 85-114. https://doi.org/10.7203/CIRIEC-E.101.18098.

Beach, D., y Vigo-Arrazola, M. B. (2018). Significados de la escuela rural desde la investigación. Representaciones compartidas entre España y Suecia en la segunda parte del siglo XX y primeros años del siglo XXI. En N. Llevot y J. Sanuy (ed.) Educació i desenvolupament rural als segles XIX-XX-XXI. Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, pp 225-236.

Berlanga, S. (2003). Educación en el medio rural: análisis, perspectivas y propuestas. Mira Editores.

Boix, R. (2004). La escuela rural: funcionamiento y necesidades. Praxis.

Boix, R. y Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2015). Escuela Rural en España: Entre la educación compensatoria y la educación inclusiva. Sísifo: Revista de Educación, 3(2), 48-59.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723-742.

Bustos Jiménez, A. (2009). Valoraciones del profesorado de escuela rural sobre el entorno presente. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 48(Extra-6), 1-11.

Bustos Jiménez, A. (2011). Investigación y escuela rural: ¿irreconciliables? Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 15(2), 155-170.

Carrete-Marín, N., & Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2021). Los recursos tecnológicos en las aulas multigrado de la escuela rural: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Brasileira de Educação do Campo, 6, e13452-e13452.

Carrete-Marín, N., & Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2023). Transformación digital y educación abierta en la escuela rural. Revista Prisma Social, (41), 95–114. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/5058

Castro, R. (2018). El desarrollo de competencias para el trabajo docente en escuelas multigrado. RIDE. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 8(16), 335-350.

Chaparro, F., & Santos, M. L. (2018). La formación del profesorado para la Escuela Rural: una mirada desde la educación física. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 21(3), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.21.3.321331

Corchón Álvarez, E., Raso Sánchez, F., & Hinojo Lucena, M. A. (2014). Análisis histórico-legislativo de la organización de la escuela rural española en el período 1857-2012. Enseñanza & Teaching: Revista Interuniversitaria De Didáctica, 31(1), 147–179. https://revistas.usal.es/tres/index.php/0212-5374/article/view/11609

Del Moral, M. E., Lopez-Bouzas, N., Fernandez-Castaneda, J., Neira-Pineiro, M., y Villalustre, L. (2023). Towards the Sustainability off Rural Schools in the Region off Asturias (Spain): Problems and Demands off Management Teams and their Coverage by the Written Press. Ager-revista de estudios sobre despoblación y desarrollo rural, 37, 67-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.4422/ager.2023.03

Fardoun, H. M., Paules Cipres, A., & Jambi, K. M. (2014). Educational Curriculum Management on Rural Environment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 122, 421-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1365

Ferrando-Félix, S., Chiva-Bartoll, O., & Peiró-Velert, C. (2019). Realidad de la educación física en la escuela rural: una revisión sistemática, Retos, 36, 604–610. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v36i36.68766

Feu, J. (2004). La escuela rural en España: apuntes sobre las potencialidades pedagógicas, relacionales y humanas de la misma. Revista Digital eRural, Educación, cultura y desarrollo rural, 2(3), 1-13

García Prieto, F. J., Álvarez-Álvarez, C. y Pozuelos Estrada, F. J. (2021). ¿Difiere la dinámica de enseñanza de las escuelas rurales del norte y sur de España? Propensión, contrastes y similitudes. Educatio Siglo XXI, 39(3), 11-36.

García Prieto, F. J., Pozuelos Estrada, F. J., & Álvarez-Álvarez, C. (2017). Uso de los libros de texto en la educación rural en España. Sinéctica, (49). Recuperado en 22 de enero de 2024, de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-109X2017000200009&lng=es&tlng=es

González, A., Bernad Cavero, O., López Teulón, M. P., Llevot Calvet, N., & Marín Marquilles, R. (2021). Las escuelas rurales desde sus debilidades hasta sus fortalezas: análisis actual. EHQUIDAD. Revista Internacional De Políticas De Bienestar Y Trabajo Social, (15), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.15257/ehquidad.2021.0006

Heredero, E. S., González, C., & Nozu, W. C. (2014). Los colegios rurales agrupados en España. Analisis del funcionamiento y organización de la escuela rural española a partir de un estudio de casos. Educação e Fronteiras, 4(12), 142-153.

Hernández, J. M. (2000). La escuela rural en la España del siglo XX. Revista de Educación, Extra-1, 113-136.

Lorenzo, J., Domingo, V., & Tomé, M. (2017). Expectativas y creencias del alumnado rural sobre su futuro profesional y académico. Aula Abierta, 45(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.45.1.2017.49-54

Lorenzo, J., Gómez, F. J. P., González, B. H., y Martínez-Pérez, A. (2021). Legislación y organización de la escuela rural en el debate en torno a la España vaciada. En M. del Mar Molero Jurado, Á. M. Martínez, A. B. B. Martín, & M. del Mar Simón Márquez (Eds.), Investigación en el ámbito escolar: variables psicológicas y educativas, pp. 463–474. Dykinson, S.L. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2gz3sv6.45

Matías Solanilla, E., & Vigo Arrazola, M. B. (2020). El valor del lugar en las relaciones de inclusión y exclusión en un colegio rural agrupado. Un estudio etnográfico. Márgenes Revista De Educación De La Universidad De Málaga, 1(2), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v1i2.8457

Monge, C., Gómez Hernández, P., & Jiménez Arenas, T. (2020). Cierre de Escuelas en Contextos Vulnerables desde la Perspectiva de los Orientadores: Impacto en Zonas Rurales. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(3), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.15366/riejs2020.9.3.020

Monge López, C., García Prieto, F. J., y Gómez Hernández, P. (2022). La escuela rural en la formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Infantil y Primaria: un campo por explorar. Profesorado: Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 26(2), 141-159. https://doi.org/10.30827/PROFESORADO.V26I2.21481

Montiel-Ruiz, F. J., & López Ruiz, M. (2023). Inteligencia artificial como recurso docente en un colegio rural agrupado. RiiTE Revista Interuniversitaria de Investigación en Tecnología Educativa, (15), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.6018/riite.592031

Morales-Romo, N. (2017). The Spanish rural school from the New Rural paradigm. Evolution and challenges for the future. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 8(2), 412-438. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.2090

Moreno, A. M. (2020). La importancia de la adecuada formación del técnico superior en educación infantil para una educación rural de calidad, excelencia y equidad. Edetania. Estudios Y Propuestas Socioeducativos. (57), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.46583/edetania_2020.57.502

Moreno, C. (2022). School in and Linked to Rural Territory Teaching Practises in Connection with the Context from an Ethnography Study. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 32(2), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v32i2.3

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C.D., & Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Pedraza-González, M., & López-Pastor, V. (2015). Investigación-acción, desarrollo profesional del profesorado de educación física y escuela rural. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte / International Journal of Medicine and Science of Physical Activity and Sport, 15(57), 1-16

Raso, F., Hinojo, M. A., & Solá, J. M. (2015). Integración y uso docente de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) en la escuela rural de la provincia de Granada: estudio descriptivo. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 13(1), 139-159.

Raso Sánchez, F., Aznar Díaz, I., & Cáceres Reche, M. P. (2014). Integración de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación: estudio evaluativo en la Escuela Rural Andaluza (España). Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, (45), 51-64.

Raso Sánchez, F., & Santana Aranda, D. (2022). Satisfacción del profesorado rural de Granada (España) respecto a su desarrollo profesional. Aula Abierta, 51(3), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.51.3.2022.275-284

Raso Sánchez, F., Sola Martínez, T., & Hinojo Lucena, F. J. (2017). Satisfacción del profesorado de la escuela rural de la provincia de Granada (España) respecto a la organización escolar. Bordón. Revista De Pedagogía, 69(2). https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2017.41372

Rothenburger, C. (2015). Towards a territorialised professional identity: the case of teaching staff in rural schools in France, Spain, Chile, and Uruguay. Sisyphus: Journal of Education, 3(2), 78-97.

Ruiz, N. y Ruiz-Gallardo, J. R. (2017). Colegios Rurales Agrupados y formación universitaria. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 21(4), 215-240.

Sánchez, F. R., Marín, J. A. M., & García, A. M. R. (2017). Análisis de la satisfacción del profesorado de la escuela rural en la provincia de Granada (España) respecto a su relación personal y profesional con la comunidad educativa. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 13(4), 27. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n4p27

Sánchez-Serrano, S., Pedraza-Navarro, I., & Donoso-González, M. (2022). ¿Cómo hacer una revisión sistemática siguiendo el protocolo PRISMA?: Usos y estrategias fundamentales para su aplicación en el ámbito educativo a través de un caso práctico. Bordón: Revista de pedagogía, 74(3), 51-66. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2022.95090

Santamaría, R. (2012). Un poco de historia de la escuela rural. Escuelarural.net http://escuelarural.net/un-poco-de-historia-enla-escuela

Santamaría, R. (2014). La escuela rural en la LOMCE. Oportunidades y amenazas. Revista Supervisión 21(33), 1-26.

Santamaría, R. (2018). La competencia global de la escuela rural en PISA 2018. Revista del Consejo Escolar de la Comunidad de Madrid, 8. Recuperado de https://www.educa2.madrid.org/web/revistadebates/articulos/-/visor/la-competencia-global-de-la-escuela-rural-en-pisa-2018

Santamaria, R. (2020). La escuela rural y las evaluaciones externas en España. PISA como ejemplo. Temps d’Educació, 59, 57-90.

Santamaría-Cárdaba, N., Sampedro, R. (2020). La escuela rural: una revisión de la literatura científica. AGER: Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural (Journal of Depopulation and Rural Development Studies), (30), 147-176. https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2020.12

Selusi, V. J., y Sanahuja, A. (2020). Aproximació a l’escolaritat inclusiva en els territoris rurals: estudi pilot sobre la veu dels docents. Kult-ur, 7(14). https://doi.org/10.6035/Kult-ur.2020.7.14.4

Tahull, J., & Montero, I. (2018). Reflexiones sobre la escuela rural. Un modelo educativo de éxito. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 32, 161-176. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2018.32.012

Tamargo, L. Á., Agudo, S., & Fombona, J. (2022). Intereses STEM/STEAM del alumnado de Secundaria de zona rural y de zona urbana en España. Educación e Investigación: Revista de la Facultad de Educación de la Universidad de São Paulo, 48(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634202248240890

Uttech, M. (2003). Imaginar, facilitar, transformar. Una pedagogía para el salón multigrado y la escuela rural. Paidós.

Villalustre, L., y Del Moral, M. E. (2011). E-actividades en el contexto virtual de ruralnet: satisfacción de los estudiantes con diferentes estilos de aprendizaje. Educación XX1, 14(1), 223-243.

Contact information: Álvaro Moraleda-Ruano. Universidad Camilo José Cela, Facultad de Educación, C/ Castillo de Alarcón 49, Urbanización Villafranca del Castillo 28692, Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid. España. E-mail: amoraleda@ucjc.edu