Students’ communicative competence and self-perception as keys to academic development in multilingual contexts

La competencia comunicativa y la autopercepción del alumnado como claves para el desarrollo académico en contextos multilingües

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-407-656

Oihana Leonet

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8801-5455

UPV/EHU

Alaitz Santos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6620-5266

UPV/EHU

Eider Saragueta

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1325-5697

UPV/EHU

Abstract

In this research study, we explored the relationship between the self-perception of communicative competence and the real competence of a group of multilingual students from the Basque Autonomous Community. Participants were 193 students from primary education (N=95) and secondary education (N=98). The main language of instruction was Basque, and Basque, Spanish and English were school subjects. All the participants filled out a self-perception competence scale in Basque, Spanish and English. Specific tests were designed and validated to measure their real communicative competence in the three languages. Two focus group discussions were conducted with teachers (N=14). The self-perception in the three languages and the scores obtained in the objective tests pointed in the same direction, but the results showed differences between groups. Both groups scored higher in self-perceptions and real competence in Spanish, but the scores differed in the order of the other two languages. Primary students scored higher in Basque while secondary students scored higher in English. The results highlight the complex interaction of some variables (context, exposure, use, age...) affecting the development of language competence in a second language.

Keywords: communicative competence, self-perception of language, multilingual education, Basque, Spanish, English.

Resumen

En este estudio exploramos la relación entre la autopercepción de la competencia comunicativa y la competencia real de un grupo de estudiantes multilingües de la Comunidad Autónoma Vasca. En el estudio participaron 193 estudiantes de Educación Primaria (N=95) y Secundaria (N=98). La principal lengua de instrucción utilizada dentro del aula era el euskera, y el castellano, el euskera y el inglés se impartían como asignaturas obligatorias. Los participantes completaron escalas de autopercepción sobre su competencia en euskera, castellano e inglés. Se diseñaron y validaron pruebas específicas para medir su competencia comunicativa real en las tres lenguas. Además, se realizaron dos grupos focales con el profesorado (n=14). La autopercepción en las tres lenguas y las puntuaciones obtenidas en las pruebas objetivas señalan en la misma dirección, pero los resultados muestran diferencias entre las dos etapas educativas. La autopercepción y la competencia real son más altas en castellano en ambos grupos, pero las puntuaciones difieren en el orden de las otras dos lenguas. El alumnado de primaria puntúa más alto en las dos mediciones en euskara mientras que el alumnado de secundaria lo hace en inglés. Los resultados ponen de manifiesto la compleja interacción entre diversos factores (entorno social, exposición, utilización, edad...) que afectan el desarrollo de la competencia lingüística en una segunda lengua.

Palabras clave: competencia comunicativa, autopercepción lingüística, educación multilingüe, euskera, castellano, inglés.

Introduction

The Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) is an increasingly multilingual society, providing an interesting context for analyzing multilingualism in education. With a population of just over two million, 43.3% of individuals over the age of two are bilingual, speaking both Basque, the minority language, and Spanish, the majority language. However, the use of Basque varies significantly and is generally lower across the provinces that make up the BAC (Eustat, 2021). In the educational system, 77.76% of Primary Education students and 72.11% of Secondary Education students study Basque as the language of instruction in the D model (Basque Government, 2022a). Since its implementation in the early 1980s, model D has been crucial in revitalizing the Basque language, enabling a significant portion of the population to acquire it. Currently, 62.4% of BAC residents have some knowledge of Basque (Eustat, 2021).

The significant growth of Basque-language instruction has substantially transformed the Basque educational system. The student body learning in Basque is now much more diverse, characterized by greater linguistic richness, varying levels of access to Basque outside of school, and differing attitudes and ideologies toward languages. Currently, most students in model D have Spanish or another language as their first language (L1) and have limited exposure to Basque outside of school. This situation affects the acquisition of the curriculum languages and other curricular areas.

This study explores the self-perception and actual language proficiency in Basque, Spanish, and English among primary and secondary school students in a city within the Basque Autonomous Community.

Multilingual Education in the Basque Autonomous Community: Challenges for the Future

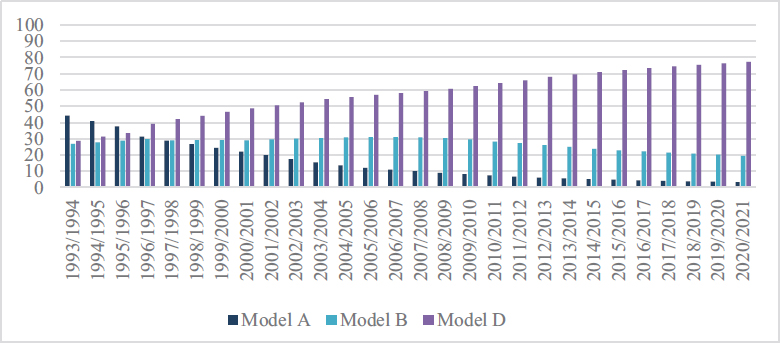

Since the late 1970s, the objective of bilingual education in the BAC has been to ensure that all students master both official languages by the end of compulsory education. Significant progress has been made toward a multilingual education system since then. One major change has been in the language of instruction parents choose for their children. As shown in Figure I, the enrolment trends for Model A (Spanish) and Model D (Basque) have diverged, with Basque now being the main language of instruction in both primary and secondary education (Eustat, 2021). Currently, Model D forms the backbone of the Basque educational system.

FIGURE I. Progression of the linguistic educational model in the BAC

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Eustat (2021).

The profile of Model D students is now more heterogeneous, with most learning through their second language (Basque), posing a significant challenge for the Basque education system (School Council of Euskadi, 2019). Current educational legislation mandates that students achieve a similar level of proficiency in Basque and Spanish by the end of compulsory schooling. Specifically, the draft Basque education law (Basque Government, 2022b) requires that all students attain B2 level communicative competence in both languages, as described by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. While developing communicative competence in both official languages is necessary, it presents a demanding linguistic challenge. In a system of linguistic immersion, as is the case for most students enrolled in Model D, achieving a high level of proficiency in the vehicular language is essential to ensure adequate learning in the other curriculum subjects.

One of the primary concerns of the educational community is reading comprehension. This issue is reflected in the results of large-scale comparative assessments. Notably, external standardized evaluations such as the diagnostic evaluation by the Basque Government and the international PISA study by the OECD (School Council of the Basque Country, 2019; National Institute for Educational Evaluation, 2018) indicate a clear downward trend in linguistic communication in Basque among students in the 4th year of Primary Education and the 2nd year of Secondary Education. The low performance of students in these assessments has been widely reported in the media, raising questions about the effectiveness of the Basque education system, particularly Model D, in educating multilingual students. Headlines such as “Model D advances, but Basque is going backward in the classrooms. What is happening?” (Guillenea, 2016) and “El Consejo Escolar de Euskadi pide una ‘reflexión’ sobre el modelo de euskaldunización por malos resultados” or “The Basque School Council calls for ‘reflection’ on the Basque language immersion model due to poor results” (Europa Press, 2020) illustrate these concerns.

While acknowledging the significance of the analyzed results, it is important to highlight that neither model A (with Spanish as the language of instruction) nor model B (with Basque and Spanish as the language of instruction) have shown improved performance in these tests. Regarding communicative competencies in Basque, both models A and B yield lower results compared to model D in diagnostic assessments. Additionally, neither model A nor B outperforms model D in Castilian (De la Rica et al., 2019).

The decline in results could be a consequence of various factors. First, it is noted that model D is becoming increasingly heterogeneous, with many students studying in their second or even third language (School Council of Euskadi, 2019). The Arrue report (Basque Government, 2020) indicates that Basque language usage among family members in the BAC stands at 29% in Primary Education and 21% in Secondary Education. Additionally, many students have limited exposure to Basque outside of school hours. Cummins (2002) introduced the concepts of BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills) and CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency) to elucidate the second language (L2) learning process for migrant students (Navarro & Huguet, 2006). These concepts are also pertinent in understanding the challenges native students face in learning an L2. BICS involves communication in the L2 within contextualized situations, while CALP pertains to academic language requiring substantial cognitive engagement and is used in decontextualized settings. This academic language comprises low-frequency vocabulary, complex syntax, and dense, abstract information, crucial for acquiring curricular knowledge and honed through academic activities during schooling. While native students may proficiently use their L2 for basic daily tasks, mastering academic language is essential for curricular competency development. Furthermore, the concept of CALS (Core Academic-Language Skills) is noteworthy, encompassing language skills crucial for reading comprehension (Meneses et al., 2018). CALS are instrumental in supporting reading comprehension across all academic subjects, even in bilingual educational settings (Phillips-Galloway et al., 2020).

The use of English in Basque society and globally is on the rise in various areas such as education (Leonet and Orcasitas-Vicandi, 2024), the workplace (van der Worp et al., 2017), and even in people’s leisure activities due to the increasing availability of digital platforms offering English-language audiovisual content (Ikusiker, 2023). In education, most students begin learning English at the age of four, and the language is also used as an additional medium of instruction in both primary and secondary schools (Cenoz, 2023). Furthermore, the prevalence of English in extracurricular activities has increased, with it now being the predominant language among secondary school students. This trend is also becoming more prominent in primary and secondary education (Basque Government, 2020). According to the Arrue report, a collaborative effort between the Basque Government and the Soziolinguistika Klusterra (Soziolinguistics Cluster) of the Basque Country (refer to Basque Government, 2020), 55.8% of 4th-grade Primary Education students engage in activities in Basque, while the percentage for 2nd-grade Compulsory Secondary Education students is 36.9%. Regarding activities in Spanish, 61.5% of 4th-grade Primary Education students report engaging in weekly activities in this language, with the percentage decreasing to 42.4% in the 2nd year of ESO. In contrast, English is the least utilized language for extracurricular activities in 4th-grade Primary Education (51.4%) but becomes the most used language in 2nd-year ESO (58%).

The Ikusiker report (2023) focuses on the entertainment habits of the young population, particularly the consumption of content on streaming platforms. The report reveals interesting insights into the language in which content is consumed on these platforms. Approximately two-thirds of the content on streaming platforms is consumed in Spanish (67.7%), while a quarter is viewed in English (26.5%). Only 0.7% of individuals regularly consume content in Basque. It is worth noting that the presence of Basque content on these platforms is minimal (Ikusiker, 2023).

Self-perception and actual communicative competence

Language learning is associated with various factors (Gardner, 2007; Hattie, 2012), one of which is an individual’s self-perception of their language proficiency. Self-perception is subjective and often involves a discrepancy between one’s actual abilities and how they perceive themselves (Deci & Flaste, 1995; Deci & Moller, 2005). It encompasses aspects of the second language (L2), such as perceived competence in grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, syntax, and pragmatics (Dewaele, 2008). Additionally, self-perceptions can be shaped by past learning experiences during the educational journey, including successes in the L2 or previous negative encounters (Dewaele, 2008; López-González, 2010).

Research on the acquisition of communicative competence suggests that the proficiency levels attained by L2 learners and users are determined by a complex interaction between psychological, affective, and sociobiographical factors (Dewaele, 2008). Dewaele (2008) proposes a series of variables associated with self-perceived linguistic competence, including factors such as the learning environment, the age of initial language acquisition, the typological distance between L1 and L2, the frequency of language use, gender, age, and education level of the individual.

Given this context, it becomes crucial to explore students’ self-perceptions of communicative competence to understand the perspectives from which they approach their academic aspirations (López-González, 2010). Often, self-perceptions differ from actual competence. For example, Alwi and Sidhu (2013) studied the relationship between university students’ self-perceived oral communicative competence and their actual competence. To assess actual competence, each student gave an oral presentation evaluated by a panel of experts. The results showed that students rated their competence higher than their actual performance. There is limited research on the self-perceived communicative competence of children and younger individuals. However, several studies have highlighted the relationship between academic performance and communicative self-perception among children (Chesebro et al., 1992; Rosenfeld et al., 1995). For instance, Chesebro et al. (1992) examined the communication attitudes of 2,793 academically at-risk students in the United States. They found that these students had higher communication apprehension and lower self-perception of communicative competence. Platsidou and Kantaridou (2014) found that self-perception is closely related to language learning strategies and attitudes toward learning. These attitudes are shaped both within the academic and broader social contexts, influencing self-perceived proficiency. Based on a sample of 1,302 primary and secondary school students, the authors reported that attitudes towards language learning affect self-perception of second language proficiency, both directly and indirectly, through improved strategy use. Their conclusions suggest that training in learning strategies can be enhanced by interventions that modify students’ attitudes toward second language learning. Additionally, Lee et al. (2003) highlight the importance of a social and cultural perspective in understanding the development of children’s self-perception of competence.

Research on the self-perception of primary and secondary school students is crucial, as many adolescents view formal education as increasingly impractical and seek alternative sources of information and skills. According to Heath (2008), from a linguistic socialization perspective, deep language habits in adolescents emerge primarily through friendships and peer interactions. This is supported by the Arrue report (Basque Government, 2020) on using Basque in school environments among children and adolescents. The report found that 66.5% of primary school students and 37.3% of secondary school students use Basque with peers in the classroom. In the playground, 40.9% of primary and 21.8% of secondary students use Basque with their classmates. In contrast, the use of Basque with teachers is higher at both educational stages, both inside and outside the classroom. Inside the classroom, 78.2% of primary students and 67.9% of secondary students use Basque, while outside the classroom, usage drops to 60.3% in primary and 40.9% in secondary (Basque Government, 2020). In multilingual educational contexts, where languages with varying statuses and societal presence coexist, self-perception is a critical variable to consider when diagnosing these environments.

Objectives and research questions

This research investigated students’ self-perceptions and actual competence in Basque, Spanish, and English. Both student and teacher perceptions of language proficiency and usage were considered. Based on the previous discussion, the following research questions were formulated:

- How do Primary and Secondary students perceive their level of proficiency in Basque, Spanish, and English?

- What is the actual proficiency of Primary and Secondary students in Basque, Spanish, and English?

- How do teachers perceive the linguistic competence of Primary and Secondary students?

Method

This research study employed a mixed methodology, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the issues than either approach alone would provide. This approach also adds complexity to the research design, incorporating the benefits of each method (Hernández et al., 2006). Following Creswell (2014), an explanatory sequential model design was chosen, emphasizing the quantitative phase, which then informs the qualitative data collected in a subsequent phase.

Sample

This research included 193 participants with an average age of 12.5 years; 49.7% were female, and 49.3% were male. The participants were divided into two groups based on age and school year. The first group consisted of 95 students in the 5th grade of Primary Education (PE), and the second group consisted of 98 students in the 3rd grade of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO). All students attended a charter school in the city center and were enrolled in model D, where Basque is the main language of instruction for all subjects except Spanish and English, which are taught for about three hours per week.

Most students’ parents had higher education degrees (father/mother1, 86.2%; father/mother2, 82%). Additionally, 73.7% of primary and 79.4% of secondary students participated in extracurricular activities in English. Regarding the sociolinguistic environment, 15.3% of the population in the town where the school is located can speak Basque (Soziolinguistika Klusterra, 2021). Table I shows the students’ language use at home, school, and with friends.

TABLE I. Use of languages by students

Location |

English |

Basque |

Both |

At home |

71.4% |

4.8% |

16% |

At school |

23.6% |

13.3% |

61.5% |

With friends |

86.2% |

2.6% |

10.8% |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Additionally, six primary and eight secondary education teachers participated in the study. Table II shows the assigned codes for the teachers, their gender, subjects taught, and years of experience in education. Primary school teachers taught Basque and Spanish language and literature, foreign language (English), social sciences, natural sciences, and mathematics. Among the secondary education teachers, in addition to the subjects above, some taught French as a second foreign language, and others taught Latin.

TABLE II. Primary and Secondary Teachers´ profile

Code |

Gender |

Subject taught |

Years of experience in education |

PE1 |

Man |

Tutoring, Mathematics and Natural Sciences |

19 years |

PE2 |

Woman |

Tutoring, Spanish Language and Literature, Basque Language and Literature |

16 years |

PE3 |

Woman |

First Foreign Language (English) |

5 years |

PE4 |

Woman |

Tutoring, Natural and Social Sciences, Spanish Language and Literature and Basque Language and Literature. |

8 years |

PE5 |

Woman |

First Foreign Language (English) |

15 years |

PE6 |

Woman |

First Foreign Language (English) |

23 years |

ESO1 |

Woman |

Tutoring, Spanish Language and Literature |

33 years |

ESO2 |

Man |

First Foreign Language (English) |

29 years |

ESO3 |

Woman |

Tutoring, Basque Language and Literature |

5 years |

ESO4 |

Woman |

First Foreign Language (English), Second Foreign Language (French) and Latin. |

27 years |

ESO5 |

Man |

Tutoring, Spanish Language and Literature |

30 years |

ESO6 |

Woman |

First Foreign Language (English) |

34 years |

ESO7 |

Woman |

Tutoring, Basque Language and Literature |

25 years |

ESO8 |

Woman |

Mathematics and ESO coordinator |

21 years |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Instruments

Data were collected using quantitative and qualitative techniques. The details of each instrument are described below.

Background questionnaire: All students completed a questionnaire to collect sociodemographic and linguistic information, including gender, age, languages used in different contexts, and exposure to different languages. Additionally, the questionnaire included a self-assessment scale of communicative competence in Basque, Spanish, and English. Students were asked to self-assess four language competencies (oral expression, written expression, oral comprehension, and reading comprehension) on a scale of 1 to 10. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (with the SPSS statistical package), yielding a score of 0.87. The questionnaire was written in Basque, the primary language of instruction at the school.

Reading comprehension tests. The reading comprehension tests were designed based on models from PIRLS and PISA tests. A total of six tests were created, three for each educational stage (primary and secondary), aimed at assessing reading comprehension in Basque, Spanish, and English. Each test comprised two written texts accompanied by nine questions pertaining to their content. In the Primary Education tests, the multiple-choice questions offered four possible answers. However, following the structure of PISA assessments, the questions included a mix of multiple-choice and open-ended formats for the Secondary Education tests. These questions were designed to evaluate literal, inferential, global, and critical comprehension of the text. Two researchers employed rubrics to ensure the validity and reliability of the correction process. They fostered reflective consensus through independent data coding, continual coding comparison, and resolving discrepancies through discussion. The internal consistency of all six tests was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (with the SPSS statistical package), yielding acceptable scores. Further details can be found in Table III.

TABLE III. Alpha Coefficients of the reading comprehension tests

Language |

Course |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Basque |

Primary Education |

.78 |

English |

Primary Education |

.78 |

English |

Primary Education |

.81 |

Basque |

Secondary Education |

.74 |

English |

Secondary Education |

.78 |

English |

Secondary Education |

.84 |

Focus groups. In addition to quantitative data, qualitative insights were gathered to supplement the information with teachers’ perspectives on students’ language proficiency and the factors influencing its development. Two focus groups were conducted—one with primary school teachers and another with secondary school teachers who taught the participating students.

A script comprising ten questions was prepared to guide the discussions. The topics covered included oral expression, written expression, oral comprehension, and reading comprehension in Basque, Spanish, and English, as well as teachers’ perceptions of students’ language use. Both focus groups were conducted in Basque and lasted approximately an hour and a half each.

Procedure

Before collecting data, students and teachers signed informed consent forms, and families were informed following the project’s ethical protocol (UPV/EHU code M10/2020/212). Quantitative data addressing the first and second research questions were analyzed using SPSS version 27. This involved conducting parametric T-tests for independent samples, with Cohen’s d used to determine effect sizes for significant differences. The third research question was addressed using qualitative data obtained from focus groups with teachers. These sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVIVO version 12 for coding and analysis.

Results

The following section will present the results corresponding to each research question.

Self-perception of primary and secondary school students

The first research question explores the self-perceptions of primary and secondary school students regarding their proficiency levels in Basque, Spanish, and English. A T-test for independent samples was conducted to ascertain whether there were disparities in self-perceptions between both groups across the three languages. Results revealed that primary school students reported a higher proficiency in Spanish, followed by Basque and English. Similarly, secondary students indicated a greater command of Spanish, followed by English and Basque. Table IV shows the means and Standard Deviation (SD) values. Notably, high SDs suggest a lack of consensus among opinions. Further analysis via t-test for independent samples revealed significant differences between the primary and secondary groups for two of the three languages: Basque (t (189) = 4.79, p = .00, d=.69) and Spanish (t (189) = 3.01, p= .00, d=.43).

TABLE IV. Self-perceived linguistic proficiency in Basque, Spanish, and English

|

Basque |

English |

English |

|||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

Primary (max.=40) |

32.01 |

4.48 |

36.91 |

2.38 |

30.13 |

5.97 |

Secondary (max.=40) |

28.20 |

6.30 |

35.27 |

4.78 |

29.50 |

5.87 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Actual language proficiency of primary and secondary school students

The second research question examines the actual proficiency of primary and secondary students in Basque, Spanish, and English. An independent samples T-test was conducted to determine if there were differences in proficiency levels between the two groups across the three languages. The results indicate that primary students scored highest in Spanish, followed by Basque and English. In contrast, secondary students scored highest in Spanish, followed by English, and then Basque. The means and standard deviations (SDs) are presented in Table V. The T-test analysis for independent samples revealed that the differences between the primary and secondary groups were significant for one of the three languages: English (t(172) = -4.52, p = .00, d = -.68). There were no significant differences for Basque (t(172) = -1.83, p = .06) and Spanish (t(172) = -1.54, p = .12).

TABLE V. Reading comprehension proficiency in Basque, Spanish, and English

|

Basque |

English |

English |

|||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

Primary (max.=9) |

5.34 |

2.15 |

5.97 |

2.25 |

4.62 |

2.39 |

Secondary (max.=9) |

4.80 |

1.73 |

6.48 |

1.80 |

6.19 |

2.19 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

As seen in Figure II, primary school students perceive their proficiency levels to be higher than the scores they obtained in the tests for all three languages. Additionally, it can be observed that both students’ self-perceptions and their actual proficiency follow the same trend across the three languages: Spanish ranks highest, Basque second, and English third.

FIGURE II. Self-perception and actual proficiency of primary school students in three languages

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The self-perception and actual proficiency of secondary school students in the three languages follow the same trend. Spanish received the highest scores in self-perception and actual proficiency, followed by English and Basque. As shown in Figure III, students perceive their proficiency levels in all three languages to be higher than their actual test scores.

FIGURE III. Self-perception and actual competence of secondary school students in the three languages

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Teachers’ perception of students’ linguistic competence

The third research question explores the perceptions of primary and secondary teachers regarding student language proficiency and use. Both language and content teachers participated in the focus groups. The qualitative analysis of these discussions provides valuable insights to complement the previous findings.

Overall, teachers express concern about their students’ communicative competence in Basque but are less worried about their competence in Spanish and English. They attribute the limitations in Basque proficiency to low exposure, either because the students’ first language at home is Spanish or due to the minimal presence of Basque in their social environment.

- Excerpt 1:

PE1: In Basque, which is the language I use, the reality of our center is that in most homes, Basque is not used; they are Spanish speakers, which has an influence.

- Excerpt 2:

PE2: The strength of the mother tongue [first language], if you have learned in Spanish, and if you live in Spanish, then when you have to study natural sciences [in Basque] in class, for example, that limits you.

The teachers generally perceive that the students have good comprehension skills. However, they think that the problem lies mainly in oral expression.

Excerpt 3:

PE2: In addition, when they talk to each other, it is clear that they lack fluency.

Excerpt 4:

EP3: But if I say correctly “erori” [caer] the student understands what I say; it is at that moment that he/she lacks fluency.

Excerpt 5:

EP4: I think they have better comprehension than fluency in speaking.

When discussing receptive skills, teachers highlight difficulties related to academic language skills and emphasize the importance of addressing these across all curricular areas. They note that proficiency in academic language directly impacts content comprehension. Some examples are provided below.

Excerpt 6:

ESO4: When they are at school and talking about school matters, they cannot speak or write like they do with their friends. They are asked for another level, another vocabulary. They are asked to do it differently, and we work on that.

Excerpt 7:

Researcher: Do you also do this in other languages, such as Basque and English?

ESO7: In Basque, yes.

ESO2: In English as well.

In the focus group with secondary education teachers, language was emphasized as an essential tool for learning. They noted that language difficulties impact all areas of study. For instance, social and natural sciences teachers pointed out that limited linguistic competence in Basque is one of the main obstacles to learning the curricular content and acquiring the academic language of their subjects.

Excerpt 8:

ESO3: In academic texts that include sentences with certain syntactic complexity, many comprehension problems arise.

Mathematics teachers also encounter this problem, although less intensely, since numerical language requires less linguistic knowledge. Nonetheless, primary education teachers highlight that one of the greatest challenges students face is solving mathematical problems, which is closely linked to their linguistic competence and academic language skills.

In general, teachers believe that the specific language of each curricular area should be addressed within each subject rather than relying solely on language teachers. This sentiment is reflected in the examples provided below:

Excerpt 9:

ESO7: It is fine to work on it in language class, but if you ask me about the hierarchy in math class, the teacher has to explain the terminology and all the language that is being worked on.

Excerpt 10:

ESO1: In my opinion in all subjects and areas, but the specific vocabulary is the competence of each subject.

Regarding the understanding of English, teachers generally believe that the students at the center have a good command of the language. However, this perception is more prevalent among secondary education teachers than primary education teachers. In the primary group, teachers noted that the activities are usually very guided, with content that is concrete and closely related to the students’ lived experiences. They suggested that if more specific and complex topics were introduced, students might experience comprehension difficulties.

Excerpt 11:

EP3: If they have to write a paper in English, it is very, very targeted. They must add a specific answer; otherwise, they cannot answer; their knowledge is limited.

Conclusions

This study investigates the relationship between the self-perceptions of primary and secondary school students and their actual communicative competence in Basque, Spanish, and English in a BAC school. The findings revealed that students’ reading comprehension test scores and self-perceived linguistic competence are closely aligned. In primary education, the highest scores in self-perception and actual proficiency were in Spanish, followed by Basque and English. These results are logical, given the students’ exposure to each language. Despite being taught only three hours a week, Spanish is the dominant language in the micro- and macro-social environment where the school is located (Soziolinguistika Klusterra, 2021) and is the L1 of most students. English is also taught for three hours a week, while Basque is the medium of instruction and is taught as a subject. In Secondary Education, the results diverge from the expected pattern based on language exposure. While Spanish remains the language with the highest scores, students performed better in English than in Basque in both self-perception and actual proficiency. This could be due to the low exposure to Basque in the social environment, contrasted with significant exposure to English outside of school and its high status in the students’ environment, which could explain the results observed for the secondary group in both measures.

From a sociolinguistic perspective on language use in the school environment, we can say that the school provides students with more favorable conditions for the development of Basque than the social context does. However, consistent with the findings of the Arrue report (Basque Government, 2020), the data indicate that the school’s ability to develop communicative competence in Basque is limited. The family and social environment offer few opportunities to use the language, which is associated with the low development of students’ communicative competence in Basque at the secondary school stage. Teachers’ opinions on linguistic competence in Basque align with these assessments, attributing the issue to low exposure to the language outside school. These results are also consistent with recent ISEI-IVEI diagnostic evaluations and PISA reports (School Council of the Basque Country, 2019; National Institute for Educational Assessment, 2018), which show a decline in reading comprehension scores in Basque in recent years.

The linguistic socialization approach (Heath, 2008) provides insight into the results regarding linguistic competence and self-perceptions among secondary school students. According to this theory, as students undergo socialization, the influence of their social environment becomes more pronounced, guided by prevailing social norms. In the specific context of the school, the social environment is considerably less supportive of Basque than the school environment, potentially affecting both the actual language proficiency and self-perception of secondary school students. Conversely, the educational center’s supportive environment toward Basque may have positively influenced the results and self-perception of primary school students regarding this language. This could be attributed to the reduced influence of the social environment at this educational stage. The Arrue report (Basque Government, 2020) also underscores the impact of the social environment on the linguistic behavior of school adolescents in the BAC. According to the report, the educational center positively influences the use of minority language among primary school students. Furthermore, Dewaele (2008) suggests that the context of language acquisition significantly influences self-perception of language proficiency, with age also playing a crucial role. Similarly, the results align with Lee et al. (2003), emphasizing the importance of the social perspective in understanding children’s self-perception of proficiency.

Diagnostic evaluations conducted by the Basque Government (Basque Government, 2020; School Council of Euskadi, 2019) suggest that the significant growth of the D model (Basque vehicular language) in recent years may contribute to the negative trend in academic development in Basque, which could also be reflected in the findings of the present study. Similar to the sample in this study, most students in the BAC are instructed in Basque as their primary language, while Spanish is their first language (L1). Originally designed for the children of Basque-speaking families, Model D has evolved into a language immersion program catering to a diverse student population. Experts in the field note that academic language proficiency is crucial in developing linguistic and academic competencies among students in language immersion programs (Cummins, 2002; Meneses et al., 2018; Phillips-Galloway et al., 2020). Teachers participating in the study observe that students encounter difficulties in understanding academic texts with certain morphosyntactic complexities. They emphasize the importance of addressing academic and subject-specific language within each curricular area.

Regarding the competence and self-perception of English, the results observed among Secondary Education students may be linked to the high value and status of English in Basque society (Basque Government, 2020; Leonet and Orcasitas-Vicandi, 2024). Additionally, exposure to English outside the school environment is substantial, owing to extracurricular activities and leisure habits such as consuming information and culture via the Internet or streaming platforms (Ikusiker, 2023). In this context, it is worth considering the socioeconomic variable (de la Rica et al., 2019), as exposure to English outside the educational setting often involves activities with an associated economic cost. The school where the data were collected was subsidized and situated in a metropolitan area populated by upper-middle-class families, most of whom have access to English resources outside of school.

Experts suggest that self-perceptions can significantly impact learning and may be influenced by previous experiences in language acquisition processes (Dewaele, 2008; López-González, 2010). Most students in the study have acquired curricular competencies in their second language (L2), Basque. Consequently, they have developed specific academic language skills in Basque and have tackled more complex academic tasks throughout their academic experience in this language. In contrast, according to teaching staff, learning English is often associated with subjects where learning occurs through experiential and more directed approaches. These differences in the learning process could have influenced the self-perceived linguistic competence of secondary students, particularly as they experience heightened exposure to academic curricular content in Basque at this stage.

The present study was conducted in a single charter school (semi-private) located in a metropolitan area. Therefore, the results may not be generalized to the broader context of the BAC. Extending the study to other public schools could yield valuable insights into the influence of socioeconomic factors on students’ self-perceptions and actual academic competence. Additionally, comparing these results with schools in sociolinguistic contexts where the Basque language has a greater presence could provide further understanding. Considering the significance of comprehension in developing other academic skills, future research could explore these aspects as variables. It would also be beneficial to investigate whether the increase in English-related activities and their social prestige affects the use of the language within and outside the school environment. An increase in English activities does not necessarily need to detract from using Basque; thus, exploring conditions for complementarity could be valuable for future studies.

Research on self-perceived communicative competence among children and young people is limited despite experts confirming its influence on second language learning. This study contributes new insights by examining the actual and self-perceived linguistic competence in Basque, Spanish, and English among multilingual students in primary and secondary education. The complex sociolinguistic environment of the study allowed for the identification of various variables related to actual communicative competence and self-perceived competence, including age and exposure to the minority language in the family and social environment. This study highlights the importance of considering psychological and sociobiographical factors in educational policies and pedagogical practices aimed at fostering the multilingual development of all students. It advocates for didactic activities that positively impact students’ communicative self-perception.

Funding

Departamento de Educación del Gobierno Vasco (código: HEZKUNTZA_13_23); Gobierno Vasco (código: IT1666-22).

Bibliogrpahic references

Alwi, N. F. B., & Sidhu, G. K. (2013). Oral presentation: Self-perceived competence and actual performance among UiTM business faculty students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 98-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.070

Cenoz, J. (2023). Plurilingual education in the Basque Autonomous Community. In J. M. Cots, Profiling plurilingual education. A pilot study of four Spanish autonomous communities (pp. 33-54). Ediciones de la Universidad de Lleida. http://digital.casalini.it/5496836

Chesebro, J. W., McCroskey, J. C., Atwater, D. F., Bahrenfuss, R. M., Cawelti, G., Gaudino, J. L., & Hodges, H. (1992). Communication apprehension and self-perceived communication competence of at-risk students. Communication Education, 41(4), 345-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529209378897

Consejo Escolar de Euskadi. (2019). Informe sobre la situación del sistema educativo vasco 2017-18/2018-19. Gobierno Vasco. https://consejoescolardeeuskadi.hezkuntza.net/es/informe-ensenanza

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (4º edición). Sage

Cummins, J. (2002). Lenguaje, poder y pedagogía. MECD-Morata.

De la Rica, S., Gortazar, L., & Vega Bayo, A. (2019). Análisis de los resultados de aprendizaje del sistema educativo vasco. Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU). https://iseak.eu/publicacion/analisis-de-los-resultados-de-aprendizaje-del-sistema-educativo-vasco

Deci, E. L., & Flaste, R (1995). Why we do what we do: Understanding self-motivation. Penguin New York.

Deci, E. L., & Moller, A. C. (2005). The concept of competence: A starting place for understanding intrinsic motivation and self-determined extrinsic motivation. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck, (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 579-597). The Guilford Press.

Dewaele, J. M. (2008). Interindividual variation in self-perceived oral proficiency of English L2 users. E.A. Soler & M. S. Jordà (Eds.) Intercultural Language Use and Language Learning (pp. 141-165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5639-0_8

Europa Press (30/09/2020). El Consejo Escolar de Euskadi pide una “reflexión” sobre el modelo de euskaldunización por malos resultados. https://www.europapress.es/sociedad/noticia-consejo-escolar-euskadi-pide-reflexion-modelo-euskaldunizacion-malos-resultados-20200930144429.html

Eustat (2021). El uso del euskera. https://es.eustat.eus/estadisticas/tema_460/opt_0/temas.html

Gardner, R. C. (2007). Motivation and second language acquisition. Porta Linguarum, 8, 9-20.

Gobierno Vasco (2020). Uso del euskera por el alumnado en el entorno escolar de la CAPV (2011-2017). Proyecto Arrue, Informe Ejecutivo.

Gobierno Vasco (2022a). Estadísticas del sistema educativo. Alumnado por nivel, modelo y red. https://www.euskadi.eus/matricula-2021-2022/web01-a2hestat/es/

Gobierno Vasco (2022b). Anteproyecto de Ley de Educación del País Vasco. https://www.euskadi.eus/informacion_publica/anteproyecto-ley-educacion-del-pais-vasco/web01-tramite/es/

Guillenea, J. (27/03/2016). El modelo D avanza, pero el euskera retrocede en las aulas. ¿Qué ocurre? https://www.elcorreo.com/bizkaia/sociedad/educacion/201603/28/modelo-avanza-pero-euskera-20160323175725.html

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge/Taylor, & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203181522

Heath, S. B. (2008). Language socialization in the learning communities of adolescents. In P.A. Duff & S. May (Eds.), Language Socialization, Encyclopedia of Language and Education (pp. 217-30). Springer International Publishing.

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2006). Metodología de la Investigación. Mc Graw Hill.

Ikusiker-Ikus-entzunezkoen behategia/Observatorio audiovisual (2023). Streaming plataformak. https://ikusiker.eus/en/txostenak/2023-2024-txosten-orokorra/

Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (2018). Informe PISA. https://isei-ivei.hezkuntza.net/es/pisa2018

Lee, J., Super, C. M., & Harkness, S. (2003). Self-perception of competence in Korean children: Age, sex and home influences. Asian journal of social psychology, 6(2), 133-147.

Leonet, O., & Orcasitas-Vicandi, M. (2024). Learning languages in a globalized world: understanding young multilinguals’ practices in the Basque Country. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45(6), 2331-2346.

López-González, M. D. (2010). Self-perceptions of communicative competence: exploring self-views among first year students in a Mexican university ‘[Tesis Doctorado, University of Nottingham]. Nottingham eTheses. https://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11340/1/PhD_Maria_Lopez_2010_Self-perception.pdf

Meneses, A., Uccelli, P., Santelices, M. V., Ruiz, M., Acevedo, D.,& Figueroa, J. (2018). Academic language as a predictor of reading comprehension in monolingual Spanish-speaking readers: Evidence from Chilean early adolescents. Reading research quarterly, 53(2), 223-247. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.192

Navarro, J. L., & Huguet, Á. (2006). Creencias y conocimiento acerca de la competencia lingüística de alumnado inmigrante. El caso de la provincia de Huesca. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 24(2), 373-394. http://hdl.handle.net/10459.1/30415

Phillips-Galloway, E., Uccelli, P., Aguilar, G., & Barr, C. D. (2020). Exploring the cross-linguistic contribution of Spanish and English academic language skills to English text comprehension for middle-grade dual language learners. AERA Open, 6(1), 373-394. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419892575

Platsidou, M., & Kantaridou, Z. (2014). The role of attitudes and learning strategy use in predicting perceived competence in school-aged foreign language learners. Journal of Language and Literature, 5(3), 253-260. https://doi.org/10.7813/jll.2014/5-3/43

Rosenfeld, L. B., Grant III, C. H., & McCroskey, J. C. (1995). Communication apprehension and self-perceived communication competence of academically gifted students. Communication Education, 44(1), 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509378999

Soziolinguistika Klusterra. (2021). Hizkuntzen erabileraren kale neurketa. Euskal Herria. 2021. https://soziolinguistika.eus/eu/proiektua/hizkuntzen-erabileraren-kale-neurketa-euskal-herria-2021-2/

van der Worp, K., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). From bilingualism to multilingualism in the workplace: The case of the Basque Autonomous Community. Language policy, 16(4), 407-432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-016-9412-4

Information address: Alaitz Santos, UPV/EHU, HEFA, Ciencias de la Educación. Tolosa Hiribidea 70, 20018 Donostia. E-mail: alaitz.santos@ehu.eus