Impact of the duration of the school transport route on the engagement of students at the lower and upper levels of compulsory education

Afectación de la duración de la ruta de transporte escolar en el compromiso académico (‘engagement’) de estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y Bachillerato

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-410-714

Laura Abellán Roselló

Universitat Jaume I

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3009-9024

Pablo Marco Dols

Universitat Jaume I

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6269-4413

Javier Soriano Martí

Universitat Jaume I

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6671-2930

Abstract

The particularities of the territory and the distribution of the population have historically led to the need to use school transport to guarantee access to education for the entire population. This generates inequalities and can have repercussions on the academic performance of the pupils transported. The article analyses the impact of travel time between home and school on academic engagement. The sample consisted of 470 students in Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate. The participants were students from 1st ESO = 18.9%, 2nd ESO = 21.9%, 3rd ESO = 15.3%, 4th ESO = 13.4%, 1st BACH = 14.0%, and 2nd BACH = 16.4%, and were between 13 and 21 years old (M = 15.63, SD = 4.25). Data were collected using the Engagement Questionnaire (MOCSE-EEQ), and the SPSS 25.00 statistical package was used. Cronbach´s alpha was performed to evaluate the questionnaire for this study, in addition to Pearson´s linear correlation analysis to test the relationship between the variables studied, one-factor ANOVA to determine the differences between the types of engagement and travel time, and simple linear regression analysis to predict engagement. The results showed that there is a relationship between the time it takes students to get to school and engagement. Furthermore, it can be affirmed that the longer the journey time, the lower the academic engagement of students. In fact, it is evident that engagement can be predicted from travel time. In conclusion, the present study can serve as a basis to support teachers in developing and promoting measures to avoid the lack of academic engagement resulting from the time students lose in getting to school.

Keywords:

School transport, engagement, secondary education, baccalaureate, quality of education

Resumen

Las particularidades del territorio y la distribución de la población provocan históricamente la necesidad de utilizar el transporte escolar para garantizar el acceso de toda la población a la educación. Esto genera desigualdades y puede llegar a tener repercusiones en el rendimiento académico del alumnado transportado. El artículo analiza las consecuencias que el tiempo de viaje entre el lugar de residencia y los centros de estudio tienen en el compromiso académico o ‘engagement’. La muestra estuvo compuesta por 470 estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) y Bachillerato. Los participantes eran estudiantes de 1º ESO = 18.9%, 2º ESO = 21.9%, 3º ESO = 15.3%, 4º ESO = 13.4%, 1º BACH = 14.0%, 2º BACH = 16.4% y tenían entre 13 y 21 años (M = 15.63, DT = 4.25). Los datos fueron recogidos mediante el Cuestionario de ‘engagement’ (MOCSE-EEQ) y se utilizó el paquete estadístico SPSS 25.00. Se realizó un alfa de Cronbach para evaluar el cuestionario para este estudio, además de un análisis de correlación lineal de Pearson para comprobar la relación entre las variables estudiadas, ANOVA de un factor para determinar las diferencias entre los tipos de ‘engagement’ y el tiempo de trayecto y análisis de regresión lineal simple para predecir el ‘engagement’ . Los resultados mostraron que existe relación entre el tiempo que tarda el alumnado en llegar al centro educativo y el ‘engagement’. Además, se puede afirmar que, a mayor tiempo de trayecto, menor compromiso académico consigue el estudiantado. De hecho, se evidencia que se puede predecir el ‘engagement’ a partir del tiempo de viaje. Como conclusión, el presente estudio puede servir de base para apoyar a los docentes a desarrollar y fomentar medidas para evitar la falta de compromiso académico derivado del tiempo que pierde el alumnado en llegar al centro escolar.

Palabras clave:

transporte escolar, compromiso académico, enseñanza secundaria, bachiller, calidad de la enseñanzaIntroduction

The advent of school transport in England in 1827 was intended to attract more students and facilitate the schooling of the entire population. At that time, horse-drawn carriages were used, which achieved their objective in very precarious conditions. These conditions were obviously different from those of the present day. The rudimentary system has evolved considerably since its inception, with journeys and itineraries now perfectly designed to improve access to education for all students, including those who live far from schools and institutes. Even until the 1960s, students sometimes had to travel several kilometres on foot to get to school. The dispersed population system, structured in many rural areas around farmhouses, hamlets, small villages, etc., (Baila, 1990; Ortells and Selma, 1993; Nabàs and Andrés, 2023) have demonstrated that universal access to education has been challenging to achieve, and for a time, this has led to the proliferation of rural schools in a variety of locations: in hermitages, completely isolated schools in equidistant areas from several inhabited locations, in the largest farmhouses or hamlets, etc. In contrast, the current legislation defines the term "transported students" as a group of students from one or more schools who require the bus service to cover the journey between their place of residence and their school or secondary school (DOGV 186 of 23 August 1984 - Regional Official Gazette).

It is a requirement that vehicles used for school transport meet very specific criteria in order to ensure the safety of their users, who are generally minors (Domínguez-Álvarez, 2019). In Spain, the current regulations pertaining to school and child transport are established by Royal Decree 443/2001, of 27 April 2001, on safety conditions in school and child transport (BOE 105 of 2 May 2001 - Official Spanish Gazette). This decree regulates a number of aspects, including the age of the vehicle, its signalling, the use of seat belts, accessibility for people with disabilities, and the maximum duration of the journey.

The issue of school transport has been a topic of discussion among teachers, students, families, regional administrations, and even the Ministry of Education since the inception of the first educational laws. This is because not all families have the option of transporting students to schools that are located far from their places of residence or in different municipalities (Pérez-Muñoz et al., 2019). This issue gained prominence with the implementation of educational reforms and the overcrowding of educational centres, particularly in rural areas, prior to the onset of the rural exodus. This was due to the limited availability of schools and institutes in scattered population areas compared to the more populated municipalities located in urban areas or their immediate areas of influence.

The activity in question is of great strategic importance in many scattered populated areas, such as rural areas. Indeed, educational provision from certain stages onwards – Secondary Education and Sixth Form, but also Vocational Training – is concentrated in the county capitals, as well as on the outskirts of medium-sized and small towns whose centres are assigned students from less populated neighbouring localities. According to data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics for the year 2019 in Spain, approximately 247 million (daily commuters during the school year) students utilize school transportation, which is facilitated by approximately 17,500 school buses (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020).

In the early stages of education, such as primary education, the problem of schooling in sparsely populated areas has been alleviated through the implementation of imaginative solutions, including rural grouped schools (RGS). These centres were established in response to the disadvantage of having rural areas with a very low student/population ratio. The rationale behind this approach was to offer dispersed classrooms in different nearby localities, which were coordinated from a larger classroom that acted as an organiser. This strategy allowed for an affordable number of students per educational level to be achieved.

It should be noted that RGS are not the only educational establishments that utilise school transport. Indeed, all such institutions can benefit from this accessibility, depending on the place of residence of their students. However, they represent one of the cases where school transport plays the most important role in Spanish education, as it is the sector with the greatest mobility among students in some areas (Flores, 2022). It is important to note that rural grouped schools have minimal visibility and recognition within the educational environment, which presents a significant challenge to their development.

In the case of secondary education, the problem is further compounded by the fact that the territorial dispersion of secondary education schools is much smaller. This results in the establishment of highly selective locations in municipalities with a minimum population, which subsequently become authentic regional capitals of reference for the educational community. These schools have a student body that can reside in towns within a radius of 30 to 60 kilometres.

At this stage, school transport affords numerous adolescent students the opportunity to pursue a comprehensive education, enabling them to study Sixth Form as a steppingstone to university studies or Certificate of Higher Education (HNC). This was previously unattainable due to the distance of the nearest school from their homes or the necessity of boarding schools, as evidenced by recent observations (Morales-Gómez, 2022).

In Spain, although the aforementioned Royal Decree 443/2001 establishes in Article 11 that the maximum journey time should not exceed one hour each way, Cruz-Carbonell et al. (2020) state that the time spent on journeys causes various kinds of inconveniences for students. The same authors also indicate that the most significant issue affecting school transport in the Secondary stage is the limited availability of vehicles to cover the journeys or the lack of investment in additional vehicles. This results in the use of the same bus to travel to different municipalities, often situated more or less in close proximity to the school. This ultimately leads to a significant loss of time for the students.

Another study by Hernández-Herrera et al. (2022) posits that unregulated timetables resulting from weather conditions and obstacles on the road, such as accidents or unforeseen traffic jams, have a direct impact on students´ education, leading to the loss of days of school compared to other students who have alternative means of getting to school. This was demonstrated by Lopes et al. (2020), who concluded that students residing in rural areas tend to exhibit lower academic performance compared to their urban counterparts, a phenomenon that can also contribute to elevated dropout rates.

Despite all this, there is still little work on how students are affected by the time it takes them to travel from home to school each day. This lack of information hinders the optimal planning of routes, journeys, and even mobility offer as a whole.

In light of these considerations, it is crucial to emphasise that students enrolled in Compulsory Secondary Education and Sixth Form face a multitude of challenges. To address these challenges and enhance their learning, it is essential to cultivate the necessary skills and competencies. This aspect is closely linked to academic engagement. In this study, we will examine the impact of students´ academic engagement on their daily school attendance. Engagement is defined as an essential variable in the educational context, as it is fundamental to achieve academic success and prevent school dropout (Zaff et al., 2017). It can be considered a key to the full development of students (Saracostti et al., 2021). The concept of engagement is understood as the involvement or bonding of the student in order to achieve academic goals. This is comprised of three interrelated but distinct dimensions: affective-emotional, cognitive and behavioural (Cerdà-Navarro et al., 2020). The affective-emotional dimension refers to students´ connection with the educational environment, including elements such as the sense of belonging to the school, relationships with peers and teachers, and also the social support they perceive (Ito and Umemoto, 2022). As for the cognitive dimension of engagement, this involves analysing the psychological involvement of students in learning, including elements such as motivation, expectations or effort to learn complex concepts (Ben-Eliyahu et al. 2018). Finally, the behavioural dimension refers to elements such as student behaviour or classroom participation, and other variables related to effort and commitment to tasks and activities or time invested (Cerdà-Navarro et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, despite the significance of establishing a correlation between the variables under investigation – namely, the time it takes students to reach their educational centres and their academic commitment or engagement – no research has been identified that directly links these variables. However, there is research that underscores the importance of linking engagement to the broader educational environment (Arrivillaga et al., 2022; Ito and Umemoto, 2022). Salmela-Aro et al. (2017), Cachón et al. (2015), Extremera et al. (2007), Leo et al. (2020), Martínez and Salanova (2003), and Ramos-Vera et al. (2023).

Objetive

The main objective of this study was to ascertain whether the duration of the journey to school affects the engagement of students in Compulsory Secondary Education and Sixth Form.

The specific objectives were as follows:

- To review whether there is a correlation between the time it takes students to reach their educational centre and their engagement levels.

- To predict engagement by considering the time it takes students to get to school.

- To ascertain whether there were significant differences in the three types of engagement measured by the time it takes students to get to school.

Method - Sample and procedure

The sample consisted of 470 students of Compulsory Secondary Education and Sixth Form. Of these, 232 were male (49.4%) and 238 female (50.6%). The participants were between 13 and 21 years old (M = 15.63, SD = 4.25). They were students of first year of Secondary Education = 18.9%, YEAR 9 = 21.9%, YEAR 10 = 15.3%, YEAR 11= 13.4%, Lower Sixth = 14.0%, Upper Sixth = 16.4%.

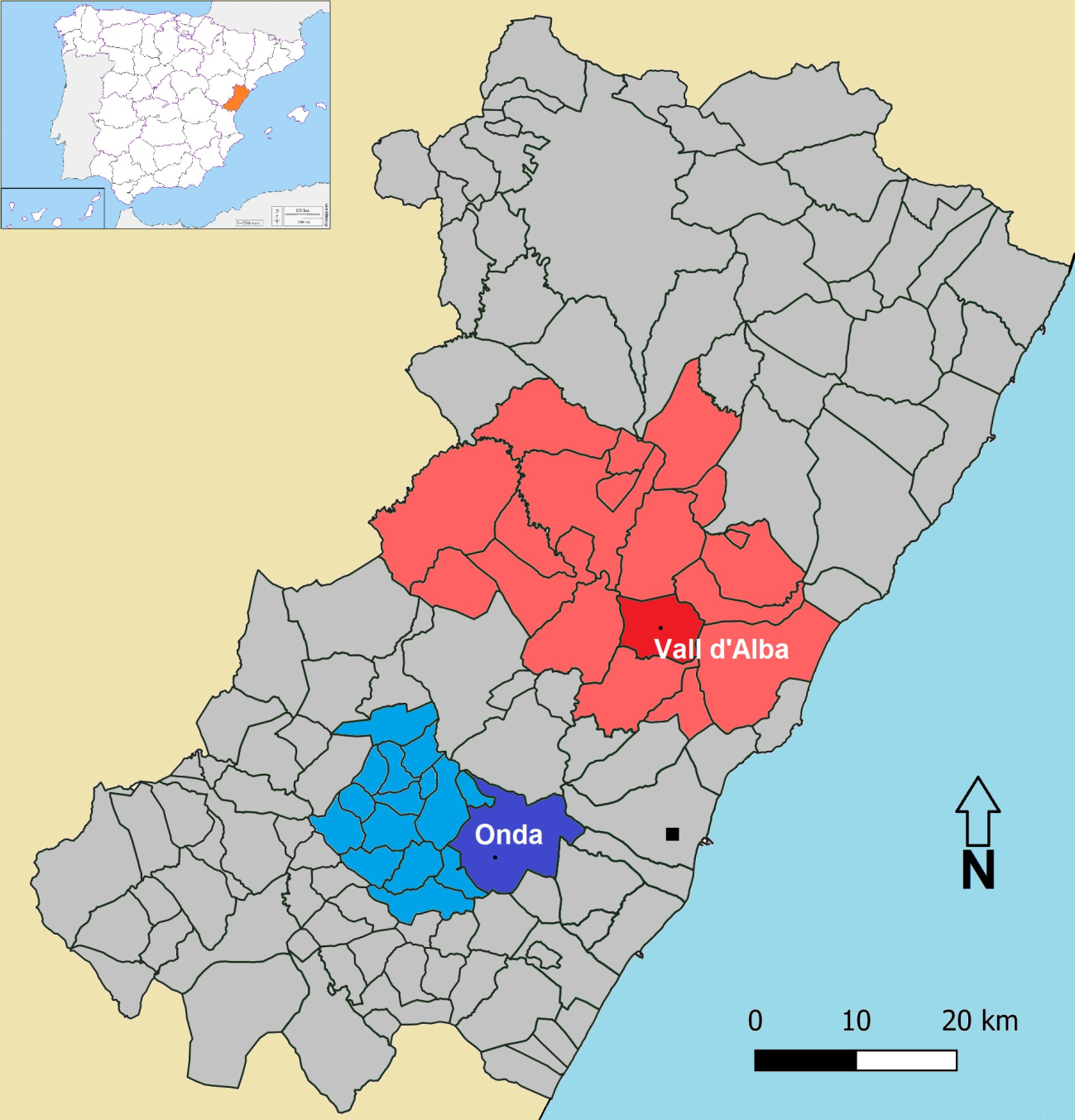

The participating schools were two secondary schools in the province of Castellón, Alfonso XIII in Vall d´Alba and Serra d´Espadà in Onda. At the time of the study, Alfonso XIII had nine school routes, the largest of which was 55.16 kilometres in each direction. Serra d´Espadà had four routes, the longest being 52.9 kilometres.

CHART I. Area of influence of each centre.

Source: Valencian Community Department of Education. Prepared by the authors.

In terms of travel time, 33.8% of students in both schools took less than 15 minutes, 28.9% took between 16 and 30 minutes, 22.2% took between 31 and 60 minutes and 15.1% took more than 61 minutes. In terms of the mode of transport used, 77.4% of students travelled by school bus, 15.1% by walking, and the remainder (7.4%) by car, bicycle, or other means of transport. Data collection was conducted during school hours for 15 minutes in the computer room, with the assistance of teachers from the participating schools.

This research was authorised by the Department of Education of the Generalitat Valenciana. Furthermore, permission was obtained from the educational centres and the prior informed consent of parents/guardians. All those who participated in the study did so on a completely voluntary basis. All data was collected in accordance with the principles of confidentiality and personal data protection, as set out in current Spanish legislation.

Instruments

The Engagement Questionnaire (MOCSE-EEQ) (Doménech-Betoret and Abellán-Roselló, 2021) adapted for this study was used. The scale is composed of 16 items divided into three dimensions: D1. Affective-emotional engagement (items 1 to 5) and D2. Cognitive engagement (items 6 to 10), Behavioural engagement (items 11 to 16). All of them are assessed on a Likert scale with 6 scalars (6 = "very high" to 0 = "very low").

This scale treats the items as quantitative, as it takes into account that the change in preference is the same when moving from one category to another, as well as using more than four scales as indicated in the literature (Doménech-Betoret and Abellán-Roselló, 2021).

In this study, Cronbach´s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire. A Cronbach´s alpha greater than .70 was determined to be an acceptable level of reliability in educational research (Cohen et al., 2018).

Specifically, it reached high values for all three subscales of the questionnaire; affective-emotional engagement (α = .882), cognitive engagement (α = .741) and behavioural engagement (α = .810). Thus, the finding of the total Cronbach´s alpha (α = .874) suggests that the overall Engagement Questionnaire also has acceptable internal consistency.

In addition, the time it takes students to get to school was measured in minutes. Time 1 (less than 15 minutes) Time 2 (between 16 and 30 minutes) Time 3 (between 31 and 60 minutes) and Time 4 (more than 61 minutes) were distinguished.

Data analysis

This study is a quantitative, non-experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive correlational design. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 25.00 package (IBM SPSS, 2018).

Associations between the different factors examined were assessed using Pearson´s correlation (r). A correlation of < .19 is considered very weak, .20 to .39 weak, .40 to .59 moderate, .60 to .79 strong and .80 very strong (for both positive and negative values) (Cohen, 1988).

Simple linear regression analyses were used to test whether engagement could be predicted by the time it takes students to get to school. In the regression analysis, the effect size of the predictor variables is given by the beta weights. When interpreting the effect, the size provides the following guidance: 0-.1 weak effect, .1-.3 moderate effect, .3-.5 moderate effect, and > .5 strong effect (Cohen, et al., 2018).

Finally, an ANOVA test was conducted on the time it takes students to get to school and the level of engagement. Main effects were tested for (p < .05), post-hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni method, and the η2p value was calculated to test the strength of the association.

Statistical significance was set at p < .01 and p < .05 for all tests.

Results

Table I shows the relationships between the factors in the Engagement Questionnaire and the time it takes students to get to school. There are moderate to strong positive and statistically significant relationships between all factors. The correlations between behavioural and affective-emotional engagement (r = .517, p < .01) or between cognitive and behavioural engagement (r = .612, p < .01) are noteworthy (see Table I).

TABLE I. Pearson´s bivariate correlations between the factors studied.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.Time of arrival at school | 1 | |||

| 2. Engagement Affec-emotional | .456** | 1 | ||

| 3. Engagement Behavioural | .355* | .517** | 1 | |

| 4. Cognitive Engagement | .372** | .498** | .612** | 1 |

**p< .01; *p< .05

Regarding the regressions on whether engagement can be predicted by the variable time students take to get to school, all three factors (affective-emotional, cognitive and behavioural) were found to be statistically significant predictors. In other words, the data conclude that engagement can be predicted by taking into account the time each student takes to get to school with a small margin of error in the three dimensions (F (18.423), ΔR2=.390) with the regression line y = 18.423x +.487+.112+.023. Affective-emotional engagement stands out as the strongest predictor and behavioural engagement the weakest. See Table II.

Table II. Results of regression analysis on engagement taking into account the time students take to get to school.

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

***p< .001

Finally, Table III shows the results of the ANOVA test corresponding to the existence of differences in the three engagement factors according to the time it takes the students to get to school. Statistically significant differences are obtained for all three factors (F (32.076), p=.000, η2p = .153; F (26.547), p=.021, η2p = .035, F (10.125), p=0.01, η2p = .130). Ex-post pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed statistically significant differences between students divided according to the time it took to get to school, with affective-emotional engagement standing out (see Table III).

TABLE III. One-factor ANOVA results for differences in engagement according to the time it takes students to get to school.

| Factors | Time | Average | SD | RMS | ANOVA test | η2p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ||||||

| Affective-emotional engagement | Time1 | 4.76 | .24 | .821 | 22.157*** | .000 | |

| Time2 | 4.89 | .35 | .255 | ||||

| Time3 | 4.27 | .31 | |||||

| Time4 | 3.44 | .42 | |||||

| Cognitive engagement | Time1 | 4.54 | .47 | .761 | 17.014** | .011 | |

| Time2 | 4.35 | .41 | .137 | ||||

| Time3 | 3.01 | .66 | |||||

| Time4 | 3.28 | .30 | |||||

| Behavioural engagement | Time1 | 4.12 | .57 | .669 | 8.483** | .031 | |

| Time2 | 4.31 | .40 | .126 | ||||

| Time3 | 3.10 | .56 | |||||

| Time4 | 3.05 | .25 | |||||

***p< .001, **p< .01, *p< .05*

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between engagement and the time it takes students to get to school. To this end, three specific objectives were set. In relation to the first specific objective 1: to relate the dimensions of engagement (affective-emotional, cognitive and behavioural) to the time variable, it can be concluded that there is a positive and significant relationship between the factors studied. A similar conclusion was reached in the study by Xu et al. (2019), which allows us to confirm that time has an impact on academic engagement. That is, taking more or less time to get to the educational centre can have an impact on students´ involvement or commitment to achieving academic goals, building interpersonal relationships among all members of the educational centre, as well as learning expectations or motivation, among others.

Regarding the second specific objective, predicting engagement through the time it takes for students to arrive at the educational centre, the results are in line with previous researches, such as Zhang et al. (2018) and Smith (2010), which conclude that the time factor has an impact on students´ academic engagement, especially the affective-emotional dimension of engagement, such as relationships with peers, teachers or family influence, so that these relationships may be more compromised if students take longer to arrive at school.

With regard to the third and final specific objective of the study, to determine whether taking more or less minutes to get to school affects engagement, the data showed that students who take longer to get to school perceive less engagement than students who arrive earlier. No studies were found to support or contradict these findings, but it is suggested that students who take longer to get to school may have a more negative relationship with their place of study and this may affect their interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers (affective-emotional engagement), their psychological involvement in the teaching and learning process, such as motivation to learn, expectations or effort to understand complex ideas and skills (cognitive engagement), and their involvement and effort (behavioural engagement) (Cerdà-Navarro et al., 2020).

This study had several limitations. On the one hand, it is worth highlighting the lack of studies on the influence of the time it takes for students to get to school and variables related to the teaching/learning process, such as engagement, a shortcoming that this work attempts to address, thus adding a novel component to the study. In addition to this drawback, there is a lack of visibility for rural schools. For future studies, it would be advisable to extend the sample to other levels of education, such as Primary Education or Vocational Training, and to other Spanish provinces with secondary and high schools, in order to verify the results of this work and compare them with other more or less similar scenarios, since the data obtained could not be used to draw conclusions or generalise the results of this research. The field of study should also be extended to other variables, such as academic satisfaction, motivation to learn or self-efficacy, variables that have been more studied in relation to the impact of using school transport to get to the education centre.

In conclusion, the present study can serve as a basis to support teachers in developing and promoting policies to avoid disengagement due to the time spent travelling to school. In addition, it can provide information for designing effective teaching projects in rural schools to improve satisfaction and academic performance. Furthermore, in order for teachers to effectively support their students, it is necessary for educational centres to provide professional development opportunities for teachers (Wendler et al., 2010), such as workshops on positive attitudes and self-confidence, as such training has a positive impact on teachers and their good practices (Haviland et al., 2010).

References

Arrivillaga, C., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2022). Recursos y

obstáculos que influyen en el rendimiento académico de los

adolescentes.

Ben-Eliyahu, A., Moore, D., Dorph, R. & Schunn, C. (2018).

Investigating the multidimensionality of engagement: Affective,

behavioral, and cognitive engagement across science activities and

contexts.

Baila, M. A. (1990).

Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), nº 105, 2 de mayo de 2001. Real Decreto 443/2001, de 27 de abril, sobre condiciones de seguridad en el transporte escolar y de menores.

Cachón, J.; Cuervo, C.; Zagalaz, M.L. & González, C. (2015).

Relación entre la práctica deportiva y las dimensiones del

autoconcepto en función del género y la especialidad que cursan los

estudiantes de los grados de magisterio.

Cerdà-Navarro, A., Salvà-Mut, F. & Sureda-García, I. (2020).

Intención de abandono y abandono durante el primer curso de Formación

Profesional de Grado Medio: un análisis tomando como referencia el

concepto de implicación del estudiante (student engagement).

Cohen, J. (1988).

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2018).

Cruz-Carbonell, V., Hernández-Arias, Ángel F., y Silva - Arias, A.

C. (2020). Cobertura de las TIC en la educación básica rural y urbana

en Colombia. Revista Científica Profundidad Construyendo Futuro,

13(13), 39–48.

Diari Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana (DOGV), nº 186, 23 de agosto de 1984. Decreto 77/1984 de 30 de julio, del Consell de la Generalitat Valenciana, sobre regulación del transporte escolar. Conselleria d’Obres Públiques, Urbanisme i Transports.

Doménech-Betoret, F. & Abellán-Roselló, L. (2021).

Domínguez-Álvarez, J.L. (2019). La despoblación en Castilla y León: políticas públicas innovadoras que garanticen el futuro de la juventud en el medio rural. En Cuadernos de Investigación en Juventud, (6), 21-36.

Extremera, N., Durán, A., & Rey, L. (2007). Inteligencia

emocional y su relación con los niveles de

Flores, E., Mora-Arias, E., Chica, J., & Balseca, M. (2022).

Evaluación de la movilidad de estudiantes y accesibilidad espacial a

centros de educación en zonas periurbanas.

Haviland, Don, Shin, Seon-Hi y Turley, Steven. (2010). Now I’m

ready: The impact of a professional development initiative on faculty

concerns with program assessment.

Hernández-Herrera, María Teresa, & Esparza-Urzúa, Gustavo

Adolfo. (2022). La calidad de la educación en territorios rurales

desde las políticas públicas.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2020). Encuesta sobre movilidad de las personas residentes en España. Resultados 2019. https://www.ine.es/prensa/emo_2019.pdf

Ito, T., & Umemoto, T. (2022). Examining the causal

relationships between interpersonal motivation, engagement, and

academic performance among university students.

IBM Corp. Released (2018).

Leo, F. M., López-Gajardo, M. A., Gómez-Holgado, J. M.,

Ponce-Bordón, J. C., & Pulido, J. J. (2020). Metodologías de

enseñanza-aprendizaje y su relación con la motivación e implicación

del alumnado en las clases de Educación Física.

Lopes, S. G., Xavier, I. M. d. C., & Silva, A. L. d. S. (2020).

Rendimento escolar: um estudo comparativo entre alunos da área urbana

e da área rural em uma escola pública do Piauí.

Martínez, B.M.T., Pérez-Fuentes, M., C., & Jurado, M.M. (2022).

Investigación sobre el Compromiso o Engagement Académico de los

Estudiantes: Una Revisión Sistemática sobre Factores Influyentes e

Instrumentos de Evaluación.

Martínez Martínez, I. M., & Salanova Soria, M. L. (2003).

Niveles de burnout y engagement en estudiantes universitarios:

Relación con el desempeño y desarrollo profesional.

Nabàs, E & Andrés, F. J. (2023).

Morales Gómez, R.

Ortells, V.; Selma, S. (1993).

Pérez-Muñoz, S., Domínguez Muñoz, R., Barrero Sanz, D., & Hernández Marín, J. (2019). Diferencias en los niveles de agilidad e IMC en los alumnos de centros rurales y no rurales en educación física. Sportis. Scientific Journal of School Sport, Physical Education and Psychomotricity, 5(2), 250-269. https://doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2019.5.2.5166

Ramos-Vera, C., Ayala-Laguna, E., & Serpa-Barrientos, A.

(2023). Efectos de la motivación académica y de la inteligencia

emocional en el compromiso académico en adolescentes peruanos de

educación secundaria.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and

burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students.

Saracostti, M., Lara, I., Rabanal, N., Sotomayor, M. B. & de

Toro, X. (2021).

Smith, J. (2010). The impact of school commute time on student

achievement and motivation.

Wendler, Cathy, Bridgeman, Brent, Cline, Fred, Millet, Catherine, Rock, JoAnn, Bell, Nathan y McAllister, Patricia. (2010). The path forward: The future of graduate education in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Servic

Xu, Y., Fan, W., & Chen, W. (2019). The impact of travel time

on academic performance: Evidence from China.

Zaff, J. F., Donlan, A., Gunning, A., Anderson, S. E., McDermott,

E. & Sedaca, M. (2017). Factors that promote high School

graduation: A review of the literature.

Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Li, Y., & Lu, L. (2018). The impact of

travel time on academic performance: The mediating roles of

self-efficacy and emotional adaptation. Transportation Research Part

A: Policy and

Información de contacto / Contact info: Laura Abellán Roselló. Universitat Jaume I. E-mail: labellan@uji.es