Key Competences in Education and General Self-efficacy. Validation of COMINT scale

Competencias Clave en Educación y Autoeficacia General. Validación de la escala COMINT

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2025-407-654

Álvaro Balaguer Estaña

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8727-4690

Universidad de Navarra

Edgar Benítez Sastoque

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7632-5109

Universidad de Navarra

Belén Serrano Valenzuela

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7058-6797

Agencia de Calidad y Prospectiva Universitaria de Aragón

Santos Orejudo Hernández

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6492-2248

Universidad de Zaragoza

Abstract

Key competences are one of the basic elements of European curricula to promote lifelong learning through education. However, there are few instruments to assess them among adolescents. For this reason, the Comprehensive Measurement of Competences (COMINT) scale was created as a global construct under the framework of Positive Psychology and Positive Youth Development. Our main objectives were to validate the COMINT scale through the variables of age and sex and analyse the relationships between Key Competencies and General Self-Efficacy. The adequate adjustment of the psychometric properties of the COMINT scale to a sample of Spanish adolescents, the statistically significant relationships between key competencies and general self-efficacy, and age and sex differences in key competencies were hypothesized. A sample of 1245 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years completed the General Self-Efficacy Scale and the COMINT scale. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses were performed to evaluate model fit in different samples. Results offered a model with an adequate construct validity and a high level of internal reliability, based on the elimination of two items from the initial scale. The instrument has shown adequate adjustment indices after modifying some initial items. The Structural Equation Model showed a significant association between Key Competences and General Self-Efficacy, with high adjustment indices. Developmental and sex differences were found, with girls in mid-adolescence being the ones who obtained lower levels on both scales. These results and the usefulness and implications of the instrument for the psychoeducational field, both scientific and applied, are discussed. We conclude that the COMINT scale constitutes an adequate and simple instrument to jointly evaluate Key Competences, construct related to General Self-Efficacy.

Keywords: key competences, general self-efficacy, positive psychology, positive youth development, statistical validation, adolescents.

Resumen

Las Competencias Clave constituyen uno de los elementos básicos de los currículos europeos para promover el aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida mediante la educación. Sin embargo, existen pocos instrumentos para evaluarlas en adolescentes. Por ello, se creó la escala de Medición Integral de Competencias (COMINT) como un constructo global bajo el marco de la Psicología Positiva y del Desarrollo Positivo Adolescente. Nuestros objetivos fueron validar la escala COMINT a través de las variables edad y sexo, analizar las relaciones entre las Competencias Clave y la Autoeficacia General, y analizar las diferencias en edad y sexo. Se plantearon como hipótesis el ajuste adecuado de las propiedades psicométricas de la escala COMINT a una muestra de adolescentes, las relaciones estadísticamente significativas entre las Competencias Clave y la Autoeficacia General, y diferencias en edad y sexo en Competencias Clave. Una muestra de 1245 adolescentes de 12 a 18 años completaron la escala de Autoeficacia General y la escala COMINT. Se realizaron análisis factoriales exploratorios y confirmatorios para evaluar el ajuste del modelo en diferentes muestras. Los resultados ofrecieron un modelo con una adecuada validez de constructo y altos niveles de ajuste y de confiabilidad interna, tras la eliminación de dos ítems de la escala inicial. El análisis de tal Modelo de Ecuaciones Estructurales mostró una asociación significativa entre las Competencias Clave y la Autoeficacia General, con altos índices de ajuste. Se hallaron diferencias evolutivas y de sexo, siendo las chicas de adolescencia media las que obtuvieron niveles más bajos en ambas escalas. Se discuten estos resultados y la utilidad e implicaciones del instrumento para el campo psicoeducativo, tanto científico como aplicado. Concluimos que la escala COMINT constituye un instrumento adecuado y sencillo para evaluar en conjunto las Competencias Clave, constructo relacionado con el de Autoeficacia General.

Palabras clave: competencias clave, autoeficacia general, psicología positiva, desarrollo positivo adolescente, validación estadística, adolescentes.

Introduction

Key Competences in Education

The use of the term “competence” has undergone numerous nuances since its first written appearance in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (Mulder et al., 2007). It was in the 1970s that applied psychology in business popularized this term to establish criteria that would allow for the “objectification” of human behavior around certain variables that are easy to observe, evaluate, select, train, or reward (Vizcaíno Candela & Medina Ruiz, 2021). However, the term “competence” began to develop in the educational field –more specifically in curricular studies– in the USA as early as the 1960s, and later spread to other countries in mastery learning models in education and vocational training, following Skinner’s work on behavioural psychology (Tahirsylaj, 2017).

Starting with UNESCO’s report “Learning: The Treasure Within” (Delors, 1996), the term “competence” was introduced into the formulation of educational policies in the European Union (EU). This report marked a shift from educational planning based on learning outcomes (Nordin & Sundberg, 2021) and emphasized the acquisition of skills throughout life in various contexts –academic, social, and professional–. Delors (1996) proposed four pillars for 21st-century education, which should serve as the foundation for educational systems: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together, and learning to be. These pillars were the genesis of key competences (KC) in education, linked to lifelong learning, across all educational levels –formal, non-formal, and informal–. Nevertheless, the terminology for competences also varies, encompassing terms such as “21st-century skills”, “lifelong learning competencies” (Nordin & Sundberg, 2021), “life skills”, “socio-emotional skills”, “soft skills”, or “transversal skills” (Sala et al., 2020).

In the 21st century, current socio-economic and cultural characteristics, as well as significant technological advances, have transformed educational institutions (European Union, 2019). These changes have reshaped national educational curricula with an epistemological and institutional rethinking, influencing the educational role of schools. In this context, the EU, as part of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), has promoted competence-based approaches (Nordin & Sundberg, 2021) that individualize and enforce lifelong learning policies (Takayama, 2013).

Competences began to be formally addressed in some educational systems through the DeSeCo (Definition and Selection of Competencies) project, launched by the OECD. DeSeCo aimed to define and select, through international agreement, the essential competencies for life and the proper functioning of society (Rychen & Salganik, 2001; 2003a; 2003b). DeSeCo conceptualized competence as the ability to successfully meet complex demands in a specific context by mobilizing psychosocial prerequisites that include cognitive and non-cognitive aspects (Rychen & Salganik, 2001) throughout life. In fact, lifelong learning involves competencies considered key in a knowledge society because they ensure greater flexibility in the labour market and better adaptation to constant change. Competence also increases students’ motivation, their attitude toward learning, and their uniqueness (European Union, 2006).

EU (2006, 2019) defined competences as a combination of knowledge (knowing), skills (knowing how to do), and attitudes (knowing how to be) appropriate to the context. The European framework for KC in education for lifelong learning, established under Recommendation 2006/962/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on KC for lifelong learning (European Union, 2006; Karatepe & Cenk, 2023), identified and defined eight KC recognized as facilitating access to employment, personal fulfillment, social inclusion, and active citizenship. They were considered essential for the well-being of European societies, economic growth and innovation, and the essential related knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Additionally, there is a particular need to develop KC during initial education and throughout life (European Union, 2006). The eight KC were as follows:

1) Communication in a mother tongue: the ability to express and interpret concepts, thoughts, feelings, facts, and opinions both orally and in writing (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), and to interact linguistically in an appropriate and creative way.

2) Communication in a foreign language: shares the main dimensions of communication skills in the mother tongue but also requires skills such as mediation and intercultural understanding.

3) Mathematical, scientific and technological competence: the ability to develop and apply mathematical thinking to solve a range of problems in everyday situations (mathematics), use knowledge and methodology to explain the natural world, identify questions, and draw evidence-based conclusions (science), and apply this in response to perceived human desires or needs (technology).

4) Digital competence: involves the confident and critical use of Information Society Technology for work, leisure, and communication.

5) Learning to learn: the ability to pursue and persist in learning, to organize one’s own learning, including through effective time and information management, both individually and in groups.

6) Social and civic competences: equip individuals to participate effectively and constructively in social and working life, solve conflicts (personal, interpersonal, and intercultural competence), and fully engage in civic life, based on knowledge of social and civic issues and political structures (civic competence).

7) Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship: the ability to turn ideas into action. It includes creativity, innovation, and risk-taking, as well as the ability to plan and manage projects to achieve objectives.

8) Cultural awareness and expression: the appreciation of the importance of creative expression of ideas, experiences, and emotions in a variety of media, including music, performing arts, literature, and visual arts.

Key Competences under Positive Psychology and Positive Youth Development frameworks

All KC are considered equally important because each can contribute to a successful life in a knowledge-based society (European Union, 2006). The EU guidelines emphasize the necessity for citizens to acquire KC as an essential condition to ensure their full personal, social, and professional development, in alignment with the demands of a globalized world, and to enable economic development linked to knowledge. This was established by the Lisbon European Council in 2000 and reaffirmed in the 2009 Council Conclusions on the Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training (“ET 2020”) (Order ECD/65/2015).

The EU’s approach (European Commission, n.d.) promotes KC through (1) Providing high-quality education, training, and lifelong learning for all; (2) Supporting educational staff in implementing competence-based teaching and learning approaches; (3) Encouraging a variety of learning approaches and contexts for lifelong learning; and (4) Exploring approaches to assess and validate KC.

This framework is consistent with both the Positive Psychology approach and the Positive Youth Development (PYD) models. Positive Psychology focuses on enhancing individuals’ positive attributes through their mindset and willpower, leading to optimal functioning (Seligman & Csíkszentmihályi, 2000; Linley & Joseph, 2004). Research under the Positive Psychology theoretical framework improves our understanding of youth development (see López et al., 2018). Indeed, the concept of PYD has been used in recent years as a synonym for promoting personal and social competences in adolescent development (see Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022; Orejudo et al., 2013; Oliva et al., 2010). PYD focuses on healthy conditions that develop skills, behaviours, and competences that enhance the social, academic, and professional youth lives. In this context, competences combine personality traits, skills, values, and knowledge that enable adolescents’ personal development in today’s society (Oliva et al., 2010).

The KC self-assessment is related to variables in Positive Psychology and PYD, such as self-concept (Oliva et al., 2010; Sundström, 2006), self-efficacy (Oliva et al., 2010; Olmos & Mas, 2018; Zimmerman et al., 2005), and self-regulation (Gómez et al., 2013; Olmos & Mas, 2018; Zimmerman et al., 2005). Additionally, the developmental perspective is crucial because it allows us to focus our research on prevention (Snyder et al., 2013), emphasizing the promotion of health and competences.

Key Competences and Self-efficacy

The numerous changes that occur throughout the various adolescent stages influence individual beliefs about competence perception. This individual perception of competence enhances youth’s self-confidence in their ability to solve problems, make decisions, and face social challenges in different contexts throughout their lives, helping them to overcome barriers (Bandura, 2006). One of the constructs of perceived competence within the framework of Positive Psychology and PYD is Self-Efficacy. This is due to its emphasis on the development of empowerment, which transforms individuals into “self-initiators” of change in their own lives and in the lives of others. In this regard, Self-Efficacy focuses on human potential and possibilities, rather than limitations, making it a truly positive psychology (Maddux, 2002).

General Self-Efficacy (GSE) is a psychological construct that reflects an individual’s perception of overall competence and adaptive skills (Bandura, 2006), which are closely related to KC. GSE represents a personal judgment about one’s abilities or competences to manage various life stressors (Bandura, 1987, 2006; Baartman & Ruijs, 2011). Based on their self-assessment of competence, individuals organize and execute actions, enabling them to achieve planned performance (Bandura, 1987).

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Baessler, 1996) has been shown to be reliable and valid for evaluating this construct. No significant differences in General Self-Efficacy have been found between sexes among Spanish adolescents (e.g., Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022; Espada et al., 2017; Orejudo et al., 2013), nor among adolescent samples from other countries (e.g., Lönnfjord & Hagquist, 2018; Marcionetti & Rossier, 2019).

However, despite the theoretical relationship between General Self-Efficacy and KC, there is a lack of literature analyzing the relationship between these two constructs.

Key Competences assessment

The KC assessment can assist students in understanding their preferred learning styles and enhancing their autonomy (European Commission, 2018). In this regard, evaluating KC helps students to recognize and communicate their competences when seeking greater learning opportunities or employment (European Union, 2019). The Recommendation 2006/962/EC (European Union, 2006) asserts that the development and validation of KC should be supported through the updating of assessment and validation tools. Indeed, assessment has a powerful impact on what is taught and learned, as well as on which competencies are developed. The recommendations to Member States regarding assessment emphasize the need to develop evaluation strategies and improve the validation of learning outcomes acquired through non-formal learning (European Commission, 2018).

Given the European Commission’s (2018) call for validated instruments to assess KC in education, there is a relevant lack of such tools. Traditionally, different scales have been used to assess various competences in university students (see Braun et al., 2012, for a review; COM-PES questionnaire, Gómez et al., 2013). These instruments are not aligned with the eight KC proposed by the EU (European Union, 2006) but rather with various classical competences related to personal and social development within the PYD framework (Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022; Orejudo et al., 2013; Oliva et al., 2010).

Object of study

In recent years, various scales have been validated to measure the degree of specific KC acquisition. Kabir & Sponseller (2020) developed a scale to assess self-efficacy perception in intercultural communication competence among a sample of Japanese teachers. Similarly, Ramírez-García et al. (2018) presented a questionnaire to evaluate the competency of knowledge and interaction with the physical world among primary education students.

Scales have also been created to assess the entire set of KC. From teacher’s perspective, Lleixà et al. (2015) developed a scale for Physical Education teachers in Primary and Secondary Education to evaluate the integration of KC into their teaching curricula. Meroño et al. (2018) validated a questionnaire to understand Primary Education teachers’ perceptions of student learning based on KC.

On the other hand, some scales evaluate the entire set of KC from the students’ perspective. For university students, Gregorová et al. (2016) proposed a scale validated on a sample of thirty Slovak adults. In adolescent population, Karatepe (2022), in their doctoral dissertation, validated a scale that assesses KC following the EU framework in Turkish population. In Spanish population, Olmos and Mas (2018) developed the AUTOCOM scale in 228 youth population aged 16 to 21 in training programs with low qualifications and early school dropout.

Therefore, there is a lack of instruments to assess KC in the normative adolescent population within the EU. Recognizing the need for an instrument to evaluate KC within the EU framework (European Union 2006, 2018, 2019), the COMINT scale was created. It was designed as one of the instruments to assess the impact of a non-formal education program (Serrano et al., 2013). Table I shows the relationships between the COMINT items and the KC in education (European Union, 2006).

TABLE I. Relation between COMINT y CC items

COMINT items |

Key Competences (KC) |

|

C1 |

I have the ability to perfectly express what I want to say. |

Communication in a mother tongue (Literacy) |

C2 |

I am able to understand and express myself in English. |

Communication in a foreign language (Multilingualism) |

C3 |

I know how to plan the financial part of projects. |

Mathematical, scientific and technological competence |

C4 |

I handle technology and social networks without problems. |

Digital competence |

C5 |

I am aware of everything I learn when I participate in extracurricular activities. |

Learning to learn |

C6 |

I meet people who are different from me and I know how to relate to them. |

Social and civic competences |

C7 |

I often propose new activities or new ways of doing things. |

Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship |

C8 |

I can explain cultural aspects of my country in a creative way. |

Cultural awareness and expression |

Source: own elaboration.

Our objectives were: 1) to validate the COMINT scale within the framework of Positive Psychology and PYD, for use in the psychoeducational field, 2) to analyze the relationships between KC and GSE constructs, and 3) to examine age and sex differences, identifying the factorial structure.

In this regard, the proposed hypotheses were as follows: 1) The psychometric properties of the COMINT scale will exhibit adequate fit indices in a sample of Spanish adolescents. 2) KC and GSE constructs will have statistically significant relationships. Previous research has not explored the relationship between KC and GSE. 3) There will be differences in KC based on age, as demonstrated by previous research (e.g., Gregorová et al., 2016), and sex (Kan & Murat, 2020; Karatepe & Cenk, 2023).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from secondary education centres. A stratified random sampling was conducted among schools in the province of Zaragoza that offered one or more types of secondary education as part of the Spanish educational system. Ten schools were randomly selected, ensuring proportional representation of public/private and urban/rural schools: seven public schools (four urban, three rural) and three urban private schools. Among these, seven schools agreed to participate: six public schools (four urban, two rural) and one urban private school. The sample consisted of 1,245 students. By age: <14 years: 55.3% (n=689), ≥14 years: 44.7% (n=556); by gender, 50.1% (n=624) female, 48.5% (n=604) male, and 1.4% (n=17) did not report either of the provided options; by school type: 640 students (51.4%) were from urban public schools, 467 (37.5%) from rural public schools, and 138 (11.1%) from urban private schools.

Instruments

Comprehensive Competence Measurement Scale (COMINT)

The COMINT scale is based on the eight KC in education from the Recommendation 2006/962/EC of the European Parliament and the Council (European Union, 2006) and is grounded in the Positive Psychology and PYD framework. It consists of 8 items with 7-point Likert scale (ranging from “nothing” to “a lot”), deemed appropriate according to Martínez-Abad and Rodríguez-Conde (2017). A total score is generated on a single factor. The items are detailed in Table I.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (Spanish adaptation by Schwarzer and Baessler, 1996, validated by Sanjuán et al., 2000)

This scale assesses the stable sense of personal competence to effectively manage a wide variety of situations across all ages. It consists of 10 items with 4-point Likert scale (“I never think this way,” “I rarely think this way,” “I often think this way,” and “I always think this way”), generating a total score on a single general self-efficacy factor. The Spanish version achieved high internal consistency (α = .87). In this study, it was .83.

Procedure

The aims and characteristics of the study were explained to school principals and counsellors. Before completing the questionnaires, families were informed by letter about the purpose and procedure of the study. Participants without parental consent were excluded. The anonymity of participants was guaranteed. Schools were informed of the possibility of excluding students whose families did not agree to their participation. Each school received a report with its own results after data analysis. Ethical guidelines for educational research were followed (British Educational Research Association, 2011). No compensation was given for participation in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from an Academic Committee of the University of Zaragoza.

Statistical procedure

Data Processing

After cleaning the records for inconsistencies in completion, assumptions for normal distribution fitting were evaluated by calculating skewness and kurtosis statistics, with cut-off points proposed by Lloret-Segura et al. (2014) [-2, 2]. Initial reliability values were estimated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and R 4.1.1 software.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

For the validation of the COMINT scale, the sample was randomly split into two groups, each containing approximately 50% of the data. One of these samples (n=602) was used for an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and the remaining sample (n=643) was used for a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). In the EFA, the factor structure was evaluated using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with α=0.05. The number of factors was confirmed using parallel analysis. Factor assignment was based on loadings greater than 0.4. Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood methods. The properties of the selected model were estimated, including item reliability, variance extraction, standardized loadings, and their respective t-test values.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The structure identified in the EFA was confirmed through CFA using maximum likelihood methods. Model fit was assessed using the statistics and cut-off points proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999): 1) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95 and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.09; or 2) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05 and SRMR < 0.06. If the fit values were not achieved, model revision was considered. Modifications were suggested using Lagrange multipliers, the Wald test, and theoretical justification. Changes to the model were accepted if the variation in the χ2 statistic was significant with p < 0.05.

Structural Equation Model (SEM)

For external validation, the GSE scale was employed within the context of SEM. In the proposed structural model, the level of KC directly influences self-efficacy.

Finally, invariance was tested across four population groups: girls and boys, older adolescents (over 14 years), and younger adolescents (under 14 years), as well as comparisons between the group mean scores.

Results

The initial evaluation of the instrument items demonstrated adequate values related to the normal distribution, so the maximum likelihood method is aligned with the subsequent parameter estimation objectives, as shown in Table II. Optimal values of the Cronbach coefficient were achieved for the required analysis (α= .80). Generally, the lowest correlation values were produced by question C2, Table II.

TABLE II. Statistics, Pearson correlation matrix between COMINT items and factor loadings

Item |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

C4 |

C5 |

C6 |

C7 |

λ |

|

C1 |

I have the ability to perfectly express what I want to say. |

-0.45 |

-0.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.583* |

C2 |

I am able to understand and express myself in English. |

-0.20 |

-0.88 |

.29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.398 |

C3 |

I know how to plan the financial part of projects. |

-0.27 |

-0.29 |

.42 |

.39 |

|

|

|

|

|

.625* |

C4 |

I handle technology and social networks without problems. |

-1.23 |

1.12 |

.31 |

.25 |

.34 |

|

|

|

|

.505* |

C5 |

I am aware of everything I learn when I participate in extracurricular activities. |

-0.92 |

0.62 |

.33 |

.27 |

.36 |

.36 |

|

|

|

.594* |

C6 |

I meet people who are different from me and I know how to relate to them. |

-0.90 |

0.44 |

.41 |

.21 |

.32 |

.35 |

.40 |

|

|

.587* |

C7 |

I often propose new activities or new ways of doing things. |

-0.32 |

-0.38 |

.36 |

.25 |

.42 |

.24 |

.41 |

.40 |

|

.649* |

C8 |

I can explain cultural aspects of my country in a creative way. |

-0.26 |

-0.49 |

.43 |

.22 |

.41 |

.24 |

.37 |

.37 |

.52 |

.637* |

Note. λ=factor loadings; * Factor loadings >0,4.

Source: own elaboration.

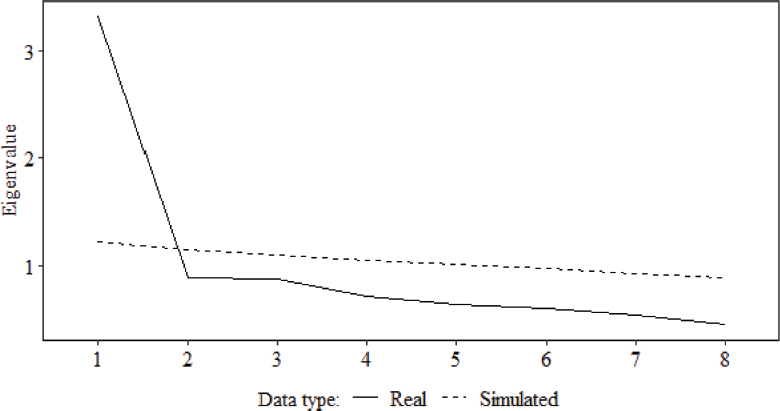

A sampling adequacy measure of KMO=.86 was obtained and the Bartlett test was rejected with p<0.01. The parallel analysis identified only one factor (observed eigenvalue = 3.32 vs. simulated critical value = 1.23), as shown in Figure I.

FIGURE I. Parallel analysis for COMINT items

Note. The number of factors prior to the intersection of the line of observed values with the simulated values indicates the number of factors identified.

Source: own elaboration.

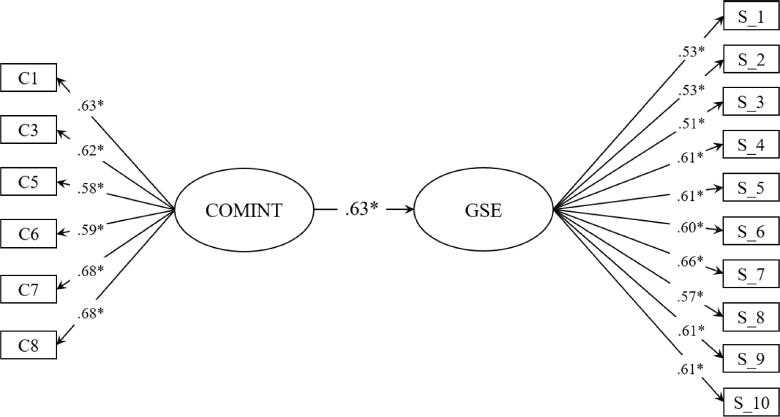

The factor loadings of the items (λ) were estimated from the selected factor. The only item that did not meet the cut-off point was C2, as shown in Figure II. However, the difference was minimal –only a few hundredths of a unit–, so it was considered for re-evaluation in the CFA to decide on its inclusion.

FIGURE II. Model with factor loadings and global correlation

Note. *p <.05.

Source: own elaboration.

In the model confirmation stage, the CFA, as initially indicated, presented all the initial items, with the exception that item C2 already presented problems of convergent validity. In the first evaluation of model confirmation, it was found that the model did not meet the cut-off points for adequate fit (RMSEA=0.096 and CFI=0.91), as shown in Table III. Therefore, modification indices were evaluated. The Wald test did not found any parameter outside of significance, unlike the Lagrange multiplier, which identified multicollinearity between items C2 and C3. Since item C2 had previously presented convergence problems, the decision was made to eliminate it from the model. In this new model, the CFI criterion still remained below the defined level (CFI=0.949). From the analysis of the Lagrange multiplier index, it was found that item C4 presented collinearity with C8. When analyzing the item, it was identified as a question related to the use of information technologies. Considering that the previously deleted item also had a technological use component, such as English proficiency, one might think that these two items should be evaluated independently.

TABLE III. Goodness-of-fit indices of the model

Model |

χ2 |

d.f. |

Δχ2 |

Δ d.f. |

Prob.>χ2 |

CFI |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

(RMSEA CL90) |

Reference model |

1393.2 |

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

original model |

139.3 |

20 |

1253.9 |

8 |

<0.01 |

0.91 |

0.051 |

0.096 |

(0.082-0.112) |

Model without C2 |

74.0 |

14 |

65.3 |

6 |

<0.01 |

0.95 |

0.040 |

0.082 |

(0.064-0.101) |

Model without C4 |

43.5 |

9 |

30.5 |

5 |

<0.01 |

0.97 |

0.033 |

0.077 |

(0.055-0.101) |

Note. χ2=chi-square; d.f.=degrees of freedom; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; SRMR= Standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA= Root mean square error of approximation; RMSEA CL90=RMSEA 90% confidence limits. The base model corresponds to the one in which the factorial structure is not considered. Δ, corresponds to the difference between the modified model versus the previous model. * p<0.05.

Source: own elaboration.

The new model evaluated without items C2 and C4 achieved optimal fit levels. Their measurement properties were estimated in this final model, as shown in Table IV. Overall, the values were very close to the optimal standards considered for these criteria: reliability >.39, composite reliability: .7 -0.9 and variance extracted >. 49.

TABLE IV. Measurement properties of the final model.

Item |

Reliability |

Standardized loading |

t-value |

Estimated variance extracted |

|

0.81a |

|

|

0.42 |

C1 |

0.42 |

0.64 |

22.68 |

|

C3 |

0.38 |

0.61 |

20.63 |

|

C5 |

0.37 |

0.61 |

20.07 |

|

C6 |

0.37 |

0.61 |

20.43 |

|

C7 |

0.47 |

0.69 |

25.73 |

|

C8 |

0.50 |

0.71 |

27.75 |

Note. a Composite reliability.

Source: own elaboration.

SEM analysis for COMINT validation as a predictor of GSE demonstrated an optimal level of fit for RMSEA, SRMR and CFI (0.05, 0.04 and 0.94, respectively), with the expected significant and positive relationship between the two constructs (β=0.63, p< 0.001), as shown in Figure II.

Finally, from the invariance analysis for the four groups (younger boys and girls, and older boys and girls), it was found that the models with no restrictions on either means or covariance structure consistently showed optimal SRMR values, and the best fit values, as shown in Table V, with the exception of the older girls. This result is in line with Hu and Bentler (1999), as they propose that this statistic is sensitive to identify problems in the covariance structure.

TABLE V. Invariance analysis for the four groups

Model |

Group |

Contribution to χ2 (%) |

SRMR |

GFI |

NFI |

Invariant |

Total |

100 |

.078 |

.98 |

.80 |

Younger boys |

19 |

.069 |

.98 |

.83 |

|

Older boys |

25 |

.080 |

.97 |

.80 |

|

Younger girls |

29 |

.070 |

.98 |

.81 |

|

Older girls |

27 |

.095 |

.97 |

.75 |

|

Variant in means and covariance structure |

Total |

100 |

.048 |

.98 |

.86 |

Younger boys |

20 |

.043 |

.99 |

.87 |

|

Older boys |

22 |

.046 |

.98 |

.88 |

|

Younger girls |

29 |

.045 |

.98 |

.86 |

|

Older girls |

30 |

.059 |

.98 |

.81 |

|

Variant in medium structure |

Total |

100 |

.066 |

.98 |

.83 |

Younger boys |

20 |

.056 |

.98 |

.85 |

|

Older boys |

23 |

.069 |

.98 |

.85 |

|

Younger girls |

28 |

.061 |

.98 |

.84 |

|

Older girls |

29 |

.079 |

.97 |

.78 |

Note. Youngers = Youngest adolescents (12-14 years old); Olders = Oldest adolescents (14-18 years old).

Source: own elaboration.

Leaving the covariance structure and means unrestricted for each subgroup, their regressors were estimated, as shown in Table VI. A pattern to highlight in the KC measurement is how the estimators’ values tend to decrease for girls when comparing older with younger ones, unlike boys, for whom almost all the regressors increase when making the transition from younger to older ones. The implications of this behavior are given when considering that these regressors measure convergence degree of the questions to the factor, which would imply that for older boys a more precise assessment of KC is being achieved compared to girls in the same age range.

TABLE VI. Comparison of covariance structure

Predictor |

Item |

MODEL (ESTIMATION, STANDARD ERROR) |

|||||

Boys |

Girls |

||||||

Younger |

Older |

Change |

Younger |

Older |

Change |

||

Key Competences (COMINT) |

C1 |

.636 (.041) |

.707 (.038) |

↑ |

.633 (.038) |

.509 (.055) |

↓ |

C3 |

.634 (.041) |

.574 (.047) |

↓ |

.699 (.034) |

.515 (.054) |

↓ |

|

C5 |

.575 (.045) |

.685 (.040) |

↑ |

.535 (.044) |

.503 (.055) |

↓ |

|

C6 |

.595 (.043) |

.643 (.043) |

↑ |

.584 (.041) |

.560 (.052) |

↓ |

|

C7 |

.677 (.038) |

.708 (.038) |

↑ |

.638 (.038) |

.681 (.045) |

↑ |

|

C8 |

.633 (.041) |

.659 (.042) |

↑ |

.740 (.032) |

.666 (.045) |

↓ |

|

General Self-efficacy (GSE) |

S_1 |

.430 (.052) |

.586 (.045) |

↑ |

.562 (.042) |

.532 (.050) |

↓ |

S_2 |

.513 (.048) |

.510 (.050) |

↓ |

.560 (.042) |

.487 (.052) |

↓ |

|

S_3 |

.501 (.048) |

.587 (.045) |

↑ |

.474 (.047) |

.518 (.050) |

↑ |

|

S_4 |

.561 (.045) |

.614 (.043) |

↑ |

.619 (.038) |

.598 (.045) |

↓ |

|

S_5 |

.603 (.042) |

.685 (.038) |

↑ |

.546 (.043) |

.568 (.047) |

↑ |

|

S_6 |

.505 (.048) |

.585 (.045) |

↑ |

.573 (.041) |

.704 (.037) |

↑ |

|

S_7 |

.654 (.039) |

.719 (.035) |

↑ |

.635 (.037) |

.637 (.042) |

↑ |

|

S_8 |

.510 (.048) |

.576 (.046) |

↑ |

.586 (.040) |

.597 (.045) |

↑ |

|

S_9 |

.570 (.044) |

.614 (.043) |

↑ |

.596 (.040) |

.632 (.043) |

↓ |

|

S_10 |

.544 (.046) |

.585 (.045) |

↑ |

.625 (.038) |

.615 (.044) |

↓ |

|

COMINT |

GSE |

.668 (.046) |

.571 (.053) |

↓ |

.677 (.041) |

.593 (.056) |

↓ |

Note. Youngers = younger adolescents (12-14 years old); Older = older adolescents (14-18 years old). The arrows indicate whether the estimated value is higher (↑) in older individuals than in younger ones, or vice versa (↓), for both girls and boys.

Source: own elaboration.

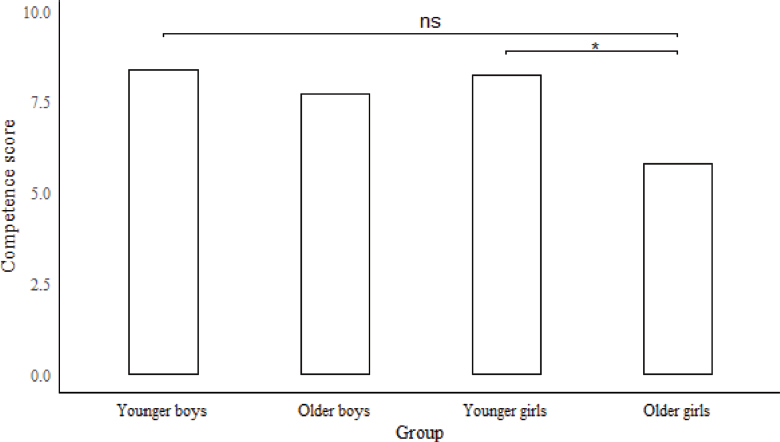

Finally, the comparison of the mean competence values between the different groups showed no differences at the α=0.05 level. However, at the α=0.1 level, it is observed that the average competence of the older girls is lower than that of the younger girls (Figure III).

FIGURE III. Contrasts of the mean values of the unrestricted model for KC score

Note. Younger = 12-14 years old; Older = 14-18 years old. Ns = not significant (p < 0.1).

*p< 0,1.

Source: own elaboration.

Discussion

The objectives of this research were to validate the COMINT scale within the framework of Positive Psychology and PYD, to examine the associations between the constructs of KC and GSE, and to analyze age and gender differences.

Regarding the first hypothesis, the psychometric characteristics of the COMINT scale, developed under the EU framework (European Union, 2006), are adequate for Spanish adolescents, though the degree of confirmation of this hypothesis requires further clarification. As for construct validity, a unifactorial model was adopted based on the consistency of the CFA. In addition to this unifactorial structure, which presents the model with the best fit among those proposed, a high internal consistency was found, demonstrating the adequacy of all items as indicators of the construct. Thus, the CFA indices reveal that the model provides an adequate approximation to the data.

The COMINT scale is valid in terms of internal structure, as reported in the original unidimensional version. However, differences were found in the factor loadings of the scale, particularly the lower indices for items C2 and C4, which address foreign language and digital competencies, respectively. It seems reasonable that not all KCs have such a close relationship with each other, as a similar functioning within a single factor would be problematic, leading to no differentiation in learning profiles. Therefore, from a theoretical standpoint, removing these items would help preserve the content validity of the instrument towards soft skills. Items C2 and C4 refer to “hard” competencies, which could represent a distinct theoretical factor. The new model evaluated without these two items achieved optimal fit levels. In fact, if the goal were to assess each of the eight competencies, a much larger instrument would be required, risking convergence to a single factor again. As a result, all competencies tend to be assessed by young people as soft skills.

It is also worth mentioning that the COMINT scale, unlike other scales that assess KC under the European Union (2006) framework, has two positive aspects: 1) it considers the items representing the EU KC, and 2) its limited number of items facilitates its implementation in fieldwork. Indeed, our aim was to create a parsimonious instrument that would assess the KC as a global construct, as part of the evaluation of an institutional non-formal education program (Serrano et al., 2013).

Following the second hypothesis, the results confirm that the constructs of KCs and GSE are statistically significantly related, as evidenced by the SEM proposed. There is evidence of convergent validity with GSE, which may reveal a similar competency profile (Bandura, 1987, 2006; Baartman & Ruijs, 2011) in adolescents. Thus, GSE serves as a source for the development of all KC, with common contextual elements for both GSE and KC. This shows that youth’s perception of general competence is related to their perception of educational competence, as expected based on previous literature (Rama & Sarada, 2017; Sundström, 2006), and this perception is relevant to the personal assets in PYD (Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022). Therefore, GSE contributes to the development of KC in adolescents. Both GSE and KC share common contextual elements. This result also confirms the external validity of the COMINT scale, as the GSE scale achieved high goodness-of-fit indices for the model.

Considering the third hypothesis, the results reveal developmental and sex differences. Indeed, the group of older girls—representing mid-adolescence—scored lower on both scales compared to the other three groups. In the case of KC, Gregorová et al. (2016) also found a decline in KC means when adolescents reach 14-15 years of age. This could be due to the increasing demands and pressures of the environment as they age (Schunk & Pajares, 2002), thus along adolescence, adolescents judge their abilities more accurately, even though these abilities may not necessarily diminish (Vecchio et al., 2007).

However, the GSE results differ from other studies with adolescent samples, both Spanish (e.g., Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022; Espada et al., 2017; Orejudo et al., 2013) and non-Spanish (e.g., Lönnfjord & Hagquist, 2018; Marcionetti & Rossier, 2019), which did not find significant sex differences in GSE. However, age or developmental stage was not controlled.

In terms of applicability, while the instrument shows adequate indicators of internal and external reliability, the COMINT scale may underestimate scores in late-mid-adolescent girls. In this regard, considering that the unifactorial instrument can be used without restrictions in younger adolescents, an instrument with more than one factor may be necessary for older adolescents. Nonetheless, the COMINT scale is a reliable and valid tool for assessing KC in adolescents in both formal and non-formal educational contexts.

Limitations

Regarding the limitations, on the one hand, the COMINT scale contains only a single item to evaluate each of the KC, which reduces the robustness of the results. However, the tool was primarily designed to assess KC as a general construct in studies aimed at analyzing their relationship with different Positive Psychology and PYD constructs, both individual and contextual, thereby minimizing participant fatigue bias. Given the limited number of items, content validation through expert judgment would enhance validity for future research.

On the other hand, only data on adolescents’ perceptions were collected. This introduced a bias that could have inflated the relationship between the different variables analyzed. For instance, the data related to values by adolescent stage again demonstrated a profile linked to biases present in other self-report instruments. Specifically, lower scores were reported in the KC of older girls compared to early adolescents of both sexes, who theoretically would have developed a lower level of competence than older girls. However, when using a self-report, subjective perception does not correspond to an external criterion, but rather to a personal value judgment. This is, undoubtedly, the major limitation of the instrument. In this case, it would be advisable to establish benchmarks linked to age groups.

As for the participants’ scores, they tend to be high across the board. This potential positive feedback bias has also been observed in other competency instruments (Baartman & Ruijs, 2011; Gómez et al., 2013; Olmos & Mas, 2018). One possible explanation for this result could be that few adolescents consider themselves lacking in competencies and self-efficacy, or because, in the case of the GSE, this scale generates a narrow range of response variation. It should also be noted that COMINT shows an invariant factorial structure across differences related to gender and adolescent stage.

In any case, this overestimation of self-perceived competency levels can be a positive and favourable element in self-regulation learning processes, as it contributes to an improved self-concept and confidence in youth’s learning potential and educational opportunities (Gómez et al., 2013). Moreover, a slight overestimation of one’s own competency level is positive, as it requires boldness, confidence, a favorable self-concept, the ability to tackle complex tasks, and persistence in the face of setbacks (Baartman & Ruijs, 2011), which are prevalent constructs in PYD models (Oliva et al., 2010).

Further research

EU (2006) advocates for the universal right to inclusive, high-quality education, training, and lifelong learning that develop KC for personal fulfillment, development, employability, social inclusion, and active citizenship. To effectively implement a competency self-assessment that fosters autonomous learning, it is essential to obtain valid and reliable instruments that assess KC in young people (European Commission, 2018) with a competency development perspective across different contexts (Balaguer et al., 2022).

The COMINT scale is precisely based on the EU’s educational policy framework (EU, 2006) and the scientific framework of Positive Psychology (López et al., 2018; Maddux, 2002) and PYD, focusing on the perception of personal and social competencies (Balaguer et al., 2020, 2022; Orejudo et al., 2013; Oliva et al., 2010). It aims to engage adolescents in the evaluation process, fostering self-reflection and feedback in learning processes within both formal and non-formal educational contexts. The scale promotes an active role in evaluation, encouraging the development of self-regulation strategies (Gómez et al., 2013; Zimmerman, 2005) and the perception of self-efficacy (Bandura, 2006; Olmos & Mas, 2018). For future research, it is useful to compare the COMINT scale with other PYD measures.

Scientifically, it is necessary to gather evidence on the relationships between KC and other Positive Psychology constructs (e.g., López et al., 2018) that promote the development of KC. Additionally, future studies should consider comparing adolescents’ KC through assessments from their parents and teachers. Furthermore, future research using the COMINT scale is needed to verify its applicability among adolescents in other countries, both in program evaluation and in Positive Psychology and development fields.

Conclusion

Considering the recommendations of the European Union (EU, 2006) and the European Commission (2018) regarding the importance of evaluating KC, the COMINT scale represents a suitable instrument for a comprehensive self-assessment of KC in a quick and simple manner. For this reason, it can be useful, on the one hand, for research in the psychoeducational field, specifically within the domains of positive psychology and PYD. Indeed, it allows for the collection of data in studies that link KC with other Positive Psychology and PYD constructs. On the other hand, in applied contexts, especially in non-formal education, the COMINT scale is appropriate for assessing KC development in young people after participating in formal or non-formal education programs.

The scale also served to help youth reflect on their perceived competences. Through this approach, the aim was not only to gather data on KC but also to ensure that the completion of the self-report involved the implementation of metacognitive strategies that stimulated self-regulation of the learning process (Baartman & Ruijs, 2011) and the recognition of self-efficacy (Rama & Sarada, 2017; Sundström, 2006). In this regard, COMINT, like other competency scales, becomes not only an instrument but also an evaluative task aimed at fostering strategic learning (Gómez et al., 2013).

References

Baartman, L., & Ruijs, L. (2011). Comparing students’ perceived and actual competence in higher vocational education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(4), 385-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.553274

Balaguer, Á., Orejudo, S. Ledo, C., & Cardoso, M. J. (2020). Extracurricular activities, positive parenting and personal positive youth development. Differential relations between sex, age, and academic trajectories. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 18(2), 179-206.

Balaguer, Á., Benítez, E., de la Fuente, J., & Osorio, A. (2022). Structural empirical model of personal positive youth development, parenting, and school climate. Psychology in the Schools, 59(3), 451-470. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22620

Bandura, A. (1987). Pensamiento y acción. Fundamentos sociales. Martínez Roca.

Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (5, 1-43). Information Age Publishing.

Braun, E., Woodley, A., Richardson, J. T., & Leidner, B. (2012). Self-rated competences questionnaires from a design perspective. Educational Research Review, 7(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.11.005

British Educational Research Association (2011). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. London: BERA. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-

Delors, J. (1996). Learning: The Treasure Within. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109590

Espada, J. P., Gonzálvez, M. T., Orgilés, M., Carballo, J. L., & Piqueras, J. A. (2017). Validación de la Escala de Autoeficacia General con adolescentes españoles. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 10(26), 355-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v10i26.1504

European Commission (n.d.). Council Recommendation on key competences for Lifelong Learning. Official website of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/education/education-in-the-eu/council-recommendation-on-key-competences-for-lifelong-learning_en

European Commission (2018). Accompanying the document Proposal for a COUNCIL RECOMMENDATION on key competences for LifeLong Learning. http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5464-2018-ADD-2/EN/pdf

European Union (2006). Recommendation 2006/962/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 18 December 2006, on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union, 394, 20.12.2006, 10-18. https://www.boe.es/doue/2006/394/L00010-00018.pdf

European Union (2018). Council Recommendation of 22 May 2018, on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union, C 189, 4.6.2018, 1-13. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604(01)&from=EN

European Union (2019, March). Key competences for Lifelong Learning. Publications Office of the European Union.

Gómez, M. A., Rodríguez, G. & Ibarra, M. S. (2013). COMPES: Autoinforme sobre las competencias básicas relacionadas con la evaluación de los estudiantes universitarios. Estudios sobre Educación, 24, 197-224.

Gregorová, A. B., Heinzová, Z., & Chovancová, K. (2016). The impact of service-learning on students’ key competences. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 4(1), 367-376.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Kabir R. S. & Sponseller A. C. (2020). Interacting With Competence: A Validation Study of the Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication Scale-Short Form. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02086

Kan, A. Ü., & Murat, A. (2020). Examining the self-efficacy of teacher candidates’ lifelong learning key competences and educational technology standards. Education and Information Technologies, 25, 707-724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10072-8

Karatepe, R. (2022). Analysis of the structural equality model of the Turkish qualifications framework key competences of secondary students and investigation of the levels of competencies. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. Mersin University.

Karatepe, R., & Cenk, A. (2023). An examination of high school students’ key competences skills. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Buca Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, (56), 649-681. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/2873683

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Appled Positive Psychology: A New Perspective for Professional Practice. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive Psychology in Practice (pp. 3-12). Wiley.

Lleixà, T., Capllonch, M., & González, C. (2015). Competencias básicas y programación de Educación Física. Validación de un cuestionario diagnóstico. Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 27, 52-57. https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/101341/1/646832.pdf

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernandez-Baeza, A., & Tomas-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Lönnfjord, V., & Hagquist, C. (2018). The psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the general self-efficacy scale: A Rasch analysis based on adolescent data. Current Psychology, 37(4), 703-715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9551-y

Lopez, S. J., Pedrotti, J. T., & Snyder, C. R. (2018). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. Sage Publications.

Maddux, J. E. (2002). Self-Efficacy: The Power of Believing You Can. In: C.R. Synder, Shane J. Lopez (Eds). Handbook of positive psychology, 277-287. Oxford university press.

Marcionetti, J., & Rossier, J. (2019). A Longitudinal Study of Relations among Adolescents’ Self-Esteem, General Self-Efficacy, Career Adaptability, and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Career Development, 48(4), 475-490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319861691

Martínez-Abad, F., & Rodríguez-Conde, M. J. (2017). Comportamiento de las correlaciones producto-momento y tetracórica-policórica en escalas ordinales: Un estudio de simulación. RELIEVE - Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.23.2.9476

Meroño, L., Calderón Luquin, A., Arias Estero, J. L., & Méndez Giménez, A. (2018). Diseño y validación del cuestionario de percepción del profesorado de Educación Primaria sobre el aprendizaje del alumnado basado en competencias (# ICOMpri2). Revista Complutense de Educación, 29(1), 215-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/RCED.52200

Mulder, M., Weigel, T., & Collins, K. (2007). The concept of competence in the development of vocational education and training in selected EU member status: a critical analisis. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 59(1), 67-88.

Nordin, A., & Sundberg, D. (2021). Transnational competence frameworks and national curriculum-making: the case of Sweden. Comparative Education, 57(1), 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1845065

Oliva, A., Ríos, M., Antolín, L., Parra, A. Hernando, A. y Pertegal, M. A. (2010). Más allá del déficit: construyendo un modelo de desarrollo positivo adolescente. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 33(2), 223-234. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037010791114562

Olmos, P. & Mas, O. (2018). Validación de AUTOCOM: autoevaluación de las competencias básicas de jóvenes en el marco de programas formativos de segunda oportunidad. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 20(4), 49-61.

Order ECD/65/2015 of January 21st, which describes the relationship between competences, contents and assessment criteria in Primary Education, Compulsory Secondary Education and Bachillerato. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 25, de 29 de enero de 2015, 6986-7003. https://boe.es/boe/dias/2015/01/29/pdfs/BOE-A-2015-738.pdf

Orejudo, S., Aparicio, L., & Cano, J. (2013). Competencias personales en estudiantes españoles que siguen distintas trayectorias académicas. Aportaciones y reflexiones desde la psicología positiva. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 5(2), 63-78. https://doi.org/10.5460/jbhsi.v5.2.42253

Rama, S., & Sarada, S. (2017). Role of self-esteem and self-efficacy on competence-A conceptual framework. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22(2), 33-39. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2202053339

Ramírez-García, A., Gutiérrez-Arenas, M. P., & Corpas-Reina, C. (2018). La competencia conocimiento e interacción con el mundo físico: autoevaluación del alumnado de Educación Primaria. Contextos Educativos. Contextos educativos, 22, 9-28. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.3132

Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2003a). Definition and selection of competencies: Theoretical and conceptual foundations (DeSeCo). Summary of the final report:” Key Competencies for a Successful Life and a Well-Functioning Society.

Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2003b). Highlights from the OECD Project Definition and Selection Competencies: Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations (DeSeCo).

Rychen, D. S., & Salganik, L. H. (2001). Defining and selecting key competencies. Hogrefe & huber publishers.

Sala, A., Punie, Y., Garkov, V., & Cabrera Giraldez, M. (2020). The European Framework for Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/302967

Sanjuán, P., Pérez, A., & Bermúdez, J. (2000). Escala de autoeficacia general: datos psicométricos de la adaptación para población española. Psicothema, 12(2), 509-513. http://www.psicothema.com/psicothema.asp?id=615

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. Wigfield & J. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 16–31). San Diego Academic Press.

Schwarzer, R., & Baessler, J. (1996). Evaluación de la autoeficacia: Adaptación española de la escala de Autoeficacia General. Ansiedad y estrés, 2(1), 1-8.

Seligman, M. E. P. & Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An Introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.5

Serrano, B., Fanjul, L. & Jiménez, N. (2013). Promoción de la salud en educación no formal. Instituto Aragonés de la Juventud.

Snyder, F., Acock, A., Vuchinich, S., Beets, M., Washburn, I. & Flay, B. (2013). Preventing negative behaviors among elementary-school students through enhancing students’ social-emotional and character development. American Journal of Health Promotion, 28(1), 50-58.

Sundström, A. (2006). Beliefs about perceived competence. A literature review. Umea University.

Tahirsylaj, A. (2017). Curriculum Field in the Making: Influences That Led to Social Efficiency as Dominant Curriculum Ideology in Progressive Era in the U.S. European Journal of Curriculum Studies 4(1), 618–628.

Takayama, K. (2013). OECD, ‘Key Competencies’ and the New Challenges of Educational Inequality. Journal of Curriculum Studies 45(1), 67–80.

Vecchio, G. M., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., Del Bove, G., & Caprara, G. V. (2007). Multi-faceted self-efficacy beliefs as predictors of life satisfaction in late adolescence. Personality and Individual differences, 43(7), 1807-1818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.05.018

Vizcaíno Candela, V. & Medina Ruiz, E. (2021). La certificación de competencias de los voluntarios como herramienta para mejorar el empleo juvenil y promover el voluntariado. Itinerarios de Trabajo Social, 1, 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1344/its.v0i1.32332

Zimmerman, B. J., Kitsantas, A., & Campillo, M. (2005). Evaluación de la autoeficacia regulatoria: una perspectiva social cognitiva. Evaluar, 5(1), 1-21. https://revistas.psi.unc.edu.ar/index.php/revaluar/article/viewFile/537/477

Contact information: Álvaro Balaguer Estaña. Universidad de Navarra, Facultad de Educación y Psicología, Departamento de Educación. Pamplona. E-mail: abalaguer@unav.es