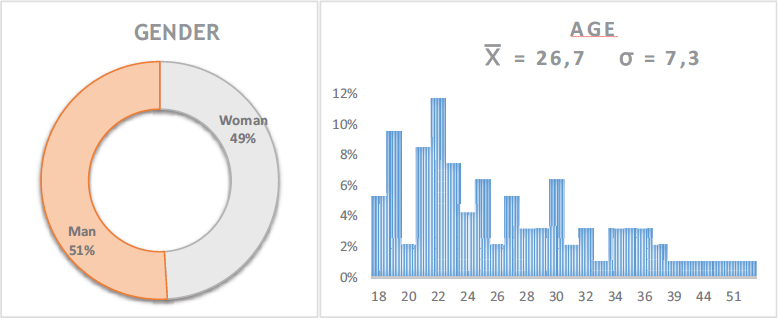

GRAPH I. Distribution of the sample by sex and age (first round, quantitative phase)

Source: own elaboration.

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-406-648

Silvia Abad Merino

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1132-3051

Universidad de Córdoba

Fernando Macías-Aranda

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1569-6659

Universidad de Barcelona

Olga Serradell Pumareda

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4077-1400

Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona

Ainhoa Flecha

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6910-9715

Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona

Abstract

Roma People, despite being the main European ethnic minority with over 600 years on the continent, continue to face discrimination and exclusion, particularly impacting their educational achievements. Only 1-4% of Roma have a university education, contrasting with 44% of other groups. Likewise, Roma individuals who enter the university system are more likely to drop out due to being non-traditional and/or first-generation students, and facing multiple forms of discrimination such as income, with a particular risk for Roma women attending university. This article is based on the results of the R&D project “UNIROMA” (2019-2022), focused on the Roma population in Spanish universities. Using Communicative Methodology, this research adopted a mixed sequential design with two phases. In the first quantitative phase, 98 responses were obtained from Roma University students. The second phase focused on qualitative data, including 20 life stories of Roma University students and 15 interviews with national and international experts. This article presents findings on sociodemographic information and the university experience of these students. Results suggest that Roma University students face difficulties related to their home environment, employment situation, and economic resources, impacting their university experience. Balancing studies, work, and family influences their academic dedication, as observed in ethnic minority and first-generation students. Exams create stress and mastering foreign languages is a common challenge. Discussion highlights the need to continue developing measures, especially within the university, to ensure the retention of Roma students, mostly first-generation, to successfully complete their university education.

Key words: university, Roma People, academic experience, non-traditional students, first-generation students.

Resumen

El Pueblo Gitano, a pesar de ser la principal minoría étnica europea con más de 600 años en el continente, sigue enfrentando discriminación y exclusión, impactando particularmente en sus logros educativos. Solo el 1-4% de los gitanos tiene educación universitaria, contrastando con el 44% de otros grupos. Asimismo, los gitanos que alcanzan el sistema universitario tienen más probabilidades de abandonar sus estudios, debido a que suelen ser estudiantes no tradicionales y/o de primera generación, y a múltiples formas de discriminación, como sus ingresos, y con un especial riesgo para las mujeres gitanas que llegan a la universidad. Este artículo se basa en los resultados del proyecto I+D “UNIROMA” (2019-2022), centrado en la población gitana de las universidades españolas. Utilizando la Metodología Comunicativa, la investigación adoptó un diseño secuencial mixto con dos fases. En la primera fase cuantitativa obtuvo 98 respuestas de estudiantes gitanos universitarios. La segunda fase se centró en datos cualitativos, con 20 historias de vida a estudiantes gitanos universitarios y 15 entrevistas a expertos nacionales e internacionales. Este artículo recoge resultados sobre la información sociodemográfica y la experiencia universitaria de estos estudiantes. Los resultados sugieren que el alumnado gitano universitario enfrenta dificultades relacionadas con la configuración de su hogar, su situación laboral o sus recursos económicos, afectando su experiencia universitaria. Equilibrar estudios, trabajo y familia influye en su dedicación académica, al igual que en estudiantes de minorías étnicas y primera generación. Los exámenes generan estrés y dominar lenguas extranjeras es un desafío común. La discusión destaca la necesidad de seguir desarrollando medidas, especialmente desde la universidad, para asegurar la permanencia de los estudiantes gitanos, en su mayoría de primera generación, para que completen con éxito la educación sus estudios universitarios.

Palabras clave: universidad, Pueblo Gitano, experiencia académica, estudiantes no tradicionales, estudiantes de primera generación.

The history of the Roma people has traditionally been associated with marginalization, poverty, and socio-educational exclusion. Although recent international initiatives have led to significant achievements about literacy and compulsory schooling for Roma communities (European Commission, 2020), Roma students continue to lead the lowest rates of academic success in the education system (Agencia de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea EU-FRA, 2022; De la Rica et al., 2019; Rutigliano, 2020).

In the university context, the data available up to 2018 indicate that in OECD countries (2020), 44.4% of adults up to the age of 34 achieved higher education. However, the Roma population with a university education is estimated to be between 1% and 4% (The Velux Foundations, 2019). Specifically, the low graduation rates of the Roma population in Spanish universities reflect the urgent need to study the difficulties faced by Roma students, as well as the evidence-based actions that contribute to overcoming them.

In recent years, significant efforts have been made in primary and secondary education to increase the Roma population accessing higher education (Brüggemann, 2014; Flecha, 2018). However, these measures need to include those mechanisms that mitigate the difficulties faced by Roma students during their university academic experience to effectively increase tertiary graduation rates. Recently, actions aimed at guaranteeing equity and inclusion of Roma students in higher education have begun to be implemented. However, the longitudinal study of the effectiveness of these initiatives and the structural barriers faced by the Roma population at university is still insufficiently developed (Garaz & Torotcoi, 2017; Rutigliano, 2020).

This study is part of the UNIROMA RTD project (2019-2022), funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, which aimed to provide scientific evidence that contributes to the success of Roma students at university, thus promoting the social inclusion of the most representative ethnic group in Spain and Europe. The project therefore made a particular contribution to Sustainable Development Goal 4, which calls for inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all.

In the field of Higher Education, the differences in the academic success of students from ethnic minority groups concerning their peers from the dominant social group begin to be defined from the conditioning factors of the previous educational stages (Lens & Levrau, 2020). Specifically, the discrimination experienced by Roma students in the education system and the difficulties that they face at the most basic school levels are documented (Lambrev, 2020).

From early childhood, Roma children face the constraints of a standardized, monocultural education system. The lack of teachers familiar with their culture makes it difficult to communicate effectively with them and their families (Bîrle et al., 2014). These challenges interact with discrimination (Eurofound, 2016; Kende et al. 2020), poverty (Kamberi et al., 2015), and sociocultural factors that affect their development in the education system (Mulcahy et al. 2017), resulting in low performance, absenteeism and high school dropout among Roma.

In the European Union, social and educational policies show barriers to access and participation that generate segregation and low educational quality for Roma (Alexiadou, 2019). Institutionalized discrimination harms minority students (Brüggemann & D'Arcy, 2017). Disconnected families often keep their children in ghetto and stigmatized schools (Neumann, 2016). Misdiagnoses due to standardized tests and socioeconomic vulnerability place them in low-quality special classrooms (Amnesty International and European Roma Rights Center, 2017; Cashman, 2017).

Official bodies confirm that Roma children are often in low-quality schools, at lower levels of education, and in segregated classrooms (Agencia de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea EU-FRA, 2016). Segregation and assignment to educational compensation groups without guarantees aggravate the educational gap (CREA, 2010; Parra Toro et al., 2017). Studying in segregated classrooms affects identity and self-esteem, and limits opportunities to stay in school (Messing, 2017).

Students from ethnic minorities face barriers in the education system that place them at a disadvantage relative to the dominant group in terms of access to higher education, due to disparities in university entrance qualifications. For example, in the United Kingdom, ethnic minority students have half the chance of earning a quality degree compared to white students (Richardson, 2018). Similarly, in Spain, Roma students are significantly below the average representation in higher education compared to the majority group (Ministry of Social Rights and Agenda 2030, 2021). This data particularly affects fields such as science and technology, as its analysis also indicates in Eastern Europe as a whole, which limits their job prospects (Garaz and Torotcoi, 2017). This highlights the need to examine how universities contribute to social injustice and to implement actions to support Roma students through academic and political engagement (Arday and Mirza, 2018).

Recent research emphasizes that effective measures are based on students' knowledge and understanding of the intersectional barriers they face as members of ethnic minorities, non-traditional and first-generation students, in addition to having unfavorable socioeconomic situations (Flecha et al., 2022). The discrimination and exclusion experienced by Roma students during their studies also interact with their learning about university dynamics and their identity (McDonagh & Fonseca, 2022). Some hide their identity for fear of being excluded, while others embrace it to normalize Roma's educational success and contribute to their community (Hinton-Smith & Padilla-Carmona, 2021; Hinton-Smith et al., 2017).

Research over the past two decades shows the deterioration of mental health and stress in ethnic minority and first-generation students (Ogunyemi et al., 2019), negatively impacting their learning experience. This is related to barriers to access, exhaustion from facing discrimination, demonstrating worth, and meeting expectations (Kundu, 2019). Stereotypical pressure also affects Roma academically, as highlighting their identity during academic tasks decreases their performance (Slobodnikova & Randolph-Seng, 2021; Želinský, 2022).

Despite university preparation programs, institutional discrimination persists for ethnic minority students. Many feel the need to educate others about race and social justice, face racial bias, and feel isolated in college (Harris & Linder, 2018). The perception that their contributions are ignored discourages underrepresented students and breeds distrust (Allaire, 2019).

The intersection of ethnicity and social class increases the difficulties in managing discrimination and marginalization in the university (Silver, 2019). This is more pronounced among Roma students, and their interaction with ethnicity predicts attitudes of prejudice (Urbiola et al., 2022). However, international mobility can be transformative for Roma students, allowing them to face discrimination and advance professionally (Marcu, 2020; Roberts, 2021).

Despite the difficulties, research on Roma students at universities in Spain is limited. This study analyzes profiles of Roma students and their academic challenges, due to the university's rigidity towards non-traditional and first-generation students. That is, students who enter university at a later age, have socioeconomic burdens or are the first in their families to study at university. Specifically, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) of the United States (2024) specifies that a non-traditional student has one or more of the following characteristics: post-norm college entry; part-time enrollment; financial independence; full-time work; with dependents other than their spouse; single-family model; or access without having earned a standard high school diploma.

The UNIROMA project was based on the Communicative Methodology that considers people as social agents with language and capacity for action, promoting dialogue between researchers, participants, and other actors involved in the realities studied. This methodological approach allows us to describe reality and contribute to its transformation through the social, political, and scientific impact generated by the research (Gómez et al., 2010).

In this research, special relevance was given to the active participation of social agents in all stages of the process, from the initial design to the formulation of conclusions. To this end, an Advisory Council was set up made up of Roma people who were studying at university, representatives of Roma associations, and people with experience in university management. Her valuable contribution was crucial to the design of fieldwork, data collection, and the identification of profiles of university students.

The research was developed using a sequential mixed method design that included two phases: an initial phase of quantitative data collection, in which Roma University students participated, and a second phase of qualitative data collection, in which both Roma University students and experts in the field of the study participated.

To address the lack of research on Roma people studying at universities in the country, an initial exploratory phase was carried out. This included a comprehensive review of the literature and the administration of an online questionnaire to Roma people enrolled in university studies at the time. The data obtained allowed the identification of different profiles of university students, which were taken into account to select the sample of the qualitative study.

The quantitative fieldwork developed during the first phase of the research was carried out during a longitudinal study that included two stages of data collection. The first stage was carried out between May and July 2020 and the second took place between April and May 2022, obtaining 98 and 51 valid responses, respectively. The profiles of the students were selected from the answers provided in the questionnaire of the first phase of the project.

In the second phase of the research, qualitative fieldwork was carried out, where 20 life stories were collected by Roma students from various universities and academic fields in Spain. In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted in this phase with 16 national and international experts with experience in university management and support programs for university students from ethnic minorities and first-generation. The results made it possible to develop recommendations for support to Roma students at university (Serradell et al., 2022).

In the quantitative phase of the study, the lack of ethnic data in Spain prevented probability sampling in this area. Instead, it was decided to use a snowball sampling method to identify the profiles of Roma students in Spanish universities. Initially, the recruitment of participants was carried out through networks established with Roma associations and was completed through the contacts they provided, to reach more individuals.

Because the Roma population in Spain is relatively small, with approximately 1,000,000 Roma people in the country and only about 1-2% of them studying at university, obtaining answers from those who met the profile analyzed in the research (Roma people enrolled in university studies) presented notable difficulties, which is one of the main limitations of the study (Schanze and Zins, 2019; Salamonska & Czeranowska, 2018). Some possibilities to increase access to the university Roma population may be the inclusion of more Roma people in the research and/or work team, the holding of events and meetings at the university aimed at students belonging to cultural and/or religious minorities, or the participation of more Roma civil society organizations, especially those who work with educational projects.

The second difficulty, as is common in longitudinal studies, was to ensure that the people who completed the initial questionnaire also completed the follow-up questionnaire, i.e. the one that was to be taken during the second round. The sample participating in the initial questionnaire included 98 Roma people who, at the time of the survey, were enrolled in regular study programs at various Spanish universities. Responses were obtained from 33 universities and 12 autonomous communities in the country, with Catalonia (42%), Andalusia (22%) and the Valencian Community (10%) standing out among them.

Regarding the distribution by age and sex, the sample is made up of 51% men and 49% women, with a mean age of 26.7 years (standard deviation, 7.3 years) with no significant differences by sex (mean age among women, 26.28; and mean age among men, 27.06).

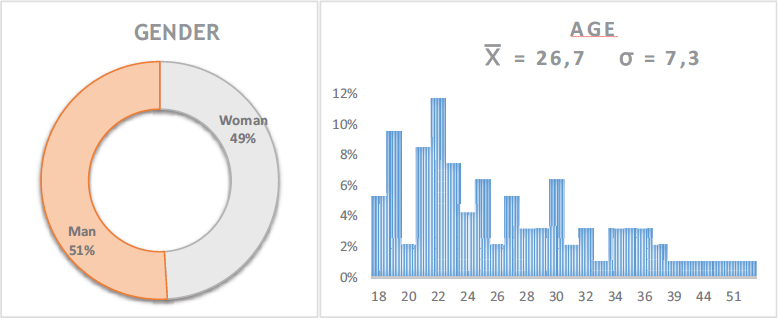

As for the second round, 51 responses were obtained from 9 Autonomous Communities, with a predominance of those from Catalonia (52.9%) and the Valencian Community (23.5%). On this occasion, the distribution by sex reflected a greater representation of men, with 57% compared to 43% of women, and a mean of 30.3 years with a standard deviation of 7.5 years.

GRAPH I. Distribution of the sample by sex and age (first round, quantitative phase)

Source: own elaboration.

GRAPH II. Distribution of the sample by sex and age (second round, quantitative phase)

Source: compiled by the authors.

Concerning the qualitative phase of the fieldwork, 20 life stories were collected from Roma students who were studying different degrees in different Spanish universities. The sample consisted of 10 women and 10 men, of which 11 lived in Catalonia and 9 in Andalusia. The student profiles were selected using the answers provided by 98 Roma University students in the questionnaire of the first phase of the project. In this way, the 20 life stories reflect diversity in terms of gender, academic profiles, and areas of knowledge, including social sciences and humanities, health sciences, and natural sciences. Most of the participants interviewed (9 women and 8 men) were enrolled in bachelor's degree programs, while 2 men and 1 woman were studying for a master's degree. In addition, 11 participants had a traditional student profile, while the remaining 9 had a non-traditional profile.

The most common routes of access to university are the most frequent, such as baccalaureate and taking the University Entrance Exams (PAU) or Higher Vocational Training with or without the PAU. However, the minority ones refer to the less common ones, such as the university entrance exam for people over 25 and 45 years of age. The selection of participants considered criteria that would allow the inclusion of the various profiles identified in the questionnaire. That is, to ensure the variety of areas of study, to balance the geographical representation with a larger Roma population, to incorporate postgraduate students without affecting the majority of undergraduate students, and to guarantee the participation of students with scholarships and those who were not associated with the Roma movement. In this way, we can reflect the diversity of trajectories and obtain relevant and meaningful information.

TABLE I. Sample profiles (qualitative phase)

|

Catalonia |

Andalusia |

||

Women |

Men |

Women |

Men |

|

Traditional student 17-24 years old, access through majority routes without work or family responsibilities. |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

Non-traditional student |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

17-24 years old, access through majority routes with work or family responsibilities. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

>25 years, access by minority routes. |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

Source: compiled by the authors.

One of the main difficulties we faced was identifying students in STEM disciplines, especially in the field of engineering. To establish contact with students, we have the collaboration of university professors and Roma associations.

To carry out the longitudinal study of the quantitative phase, two instruments have been developed in online format: an initial questionnaire and a follow-up questionnaire. In designing the initial questionnaire, the research team collaborated with the Advisory Board and, in particular, with CampusRom - University Roma Network, an association that brings together Roma students. Previous questionnaires on university trajectories in general and ethnic minority students in particular were used as a basis, such as the Student Experience Survey (Times Higher Education, 2018), the psychopedagogical characterization questionnaire of university students (Márquez & Ordaz, 2014), the CEVEAPEU questionnaire (Gargallo et al., 2009), the NSSE (Center for Postsecondary Research, 2019) and the First Generation College Survey (Students for Education Reform, 2017).

The initial questionnaire was validated through piloting to ensure its feasibility, reliability, and validity, as well as to adjust the time needed to complete it. After making the pertinent modifications, the final questionnaire was generated, which consists of 86 items and the following thematic blocks:

The follow-up questionnaire focused on knowing the progress of the students initially interviewed about their university studies, including whether they were still studying, whether they had graduated or dropped out, and what were the main difficulties they faced.

To carry out the qualitative phase, life stories made by Roma University students were used and in-depth interviews were conducted with experts.

The life stories addressed the following topics:

In the interviews with the experts, aspects related to 1) Support, accompaniment, and information programs were addressed; 2) Financial aid; and 3) Social participation. All these measures were found to be linked to students from ethnic and/or non-traditional minorities (second generation, over 25 years of age, work and/or family responsibilities).

This article shows the results of the quantitative and qualitative phase of the study, linked to the sociodemographic and academic information of the students. Specifically, the analysis includes:

– Form of cohabitation and household data

– Employment and economic situation

– Study Resources

– Family cultural capital

– Academic dedication

– Self-sufficiency

The results obtained show sociodemographic and academic information related to the barriers experienced by Roma University students in their careers.

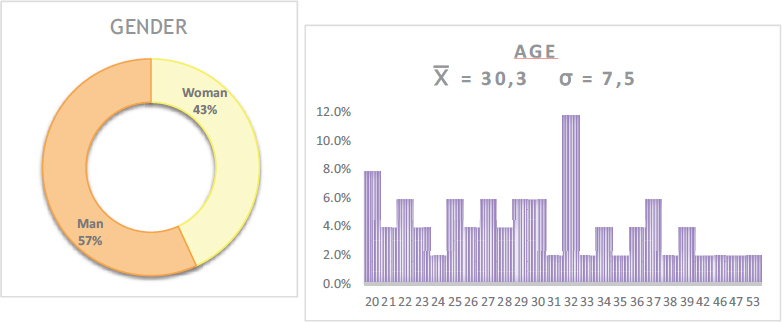

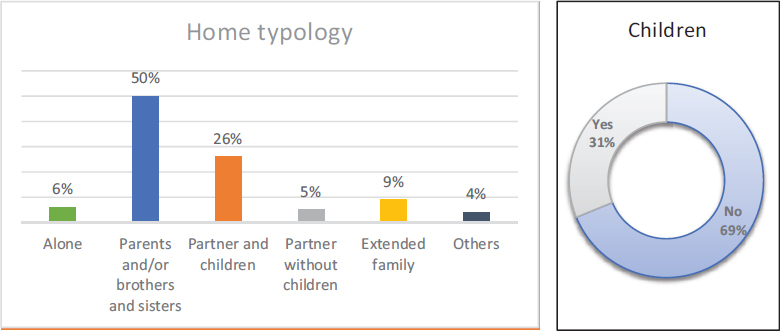

Most of the students in the sample live with their parents and/or siblings (50%). However, the proportion of emancipated students reaches almost half of the sample, considering that 31% live with a partner (26% with children and 5% only with their partner) and 6% live alone. Bearing in mind that 26% of the sample has children, it is relevant to note that family responsibilities constitute a difficulty in monitoring studies, both because of the time they entail and because the need to generate their own economic resources increases. In addition, participants live in large family units, with an average of 4.26 members and a standard deviation of 1.73.

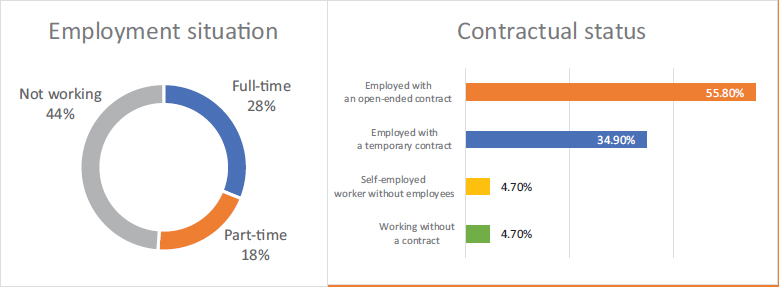

46% of the participants work, either part-time (18%) or full-time (28%). Regarding the contractual situation, 56% have permanent contracts while 35% have temporary contracts. To these, we should add almost 5% of self-employed workers and the same percentage of people who work without a contract.

GRAPH III. Type of household and children (%)

Source: compiled by the authors.

GRAPH IV. Employment and contractual status (%)

Source: compiled by the authors.

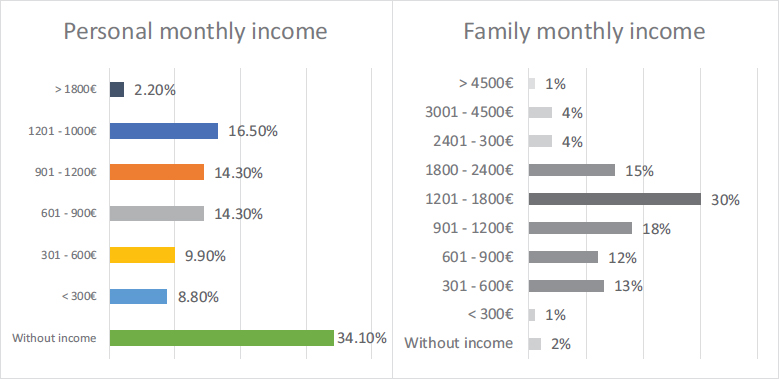

The analysis of the data relating to income shows a situation of economic precariousness, with an average family income of €1411 (with a deviation of €924), which can be related to the average size of the household that frequently exceeds 4 members.

The students interviewed highlight the economic precariousness and the stress component associated with the lack of income security and stable housing.

GRAPH V. Personal and family monthly income (%)

Source: own elaboration.

Out of ten subjects, I have three left and they are costing me because we have a more humble lifestyle. We always have to shoot, with Primo or with whoever. We have had two or three evictions because we do not have the money to pay the rent and all this has an impact, it is more complicated than another person who has their own house and their income... (José, non-traditional student, social sciences and humanities, Andalusia).

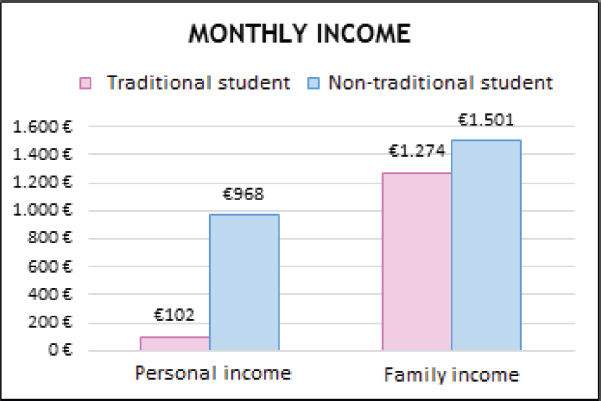

The analysis according to the student profile, non-traditional students, being older and working longer hours, have significantly higher incomes than traditional students.

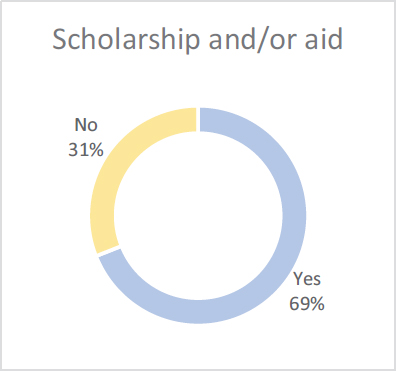

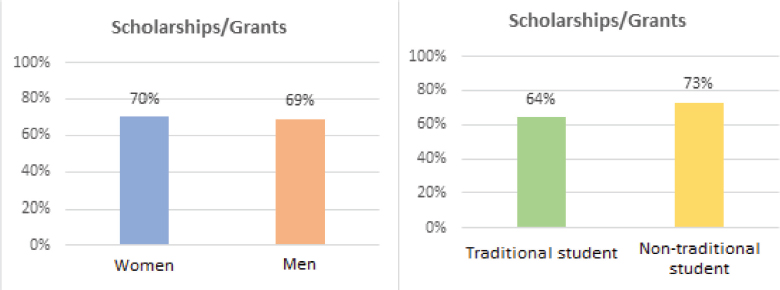

In line with this economic situation, the data show that 69% receive some type of scholarship or study support. These data are consistent with the socioeconomic position of the Roma population in Spain, which represents a barrier to the follow-up of post-compulsory studies. In addition, the receipt of the general grant from the Ministry usually puts added pressure on university students. Generally, the strict academic criteria imposed to maintain it can be difficult for those students who have to combine studies with other work and/or family obligations.

GRAPH VI. Monthly income according to student profile (€)

Source: compiled by the authors.

GRAPH VII. Beneficiaries of some type of scholarship and/or aid (%)

Source: compiled by the author

Specifically, the perception of students concerning the rigid criteria for obtaining the general scholarship shows the difficulties it implies for those people with more unfavorable life circumstances.

I have had scholarships luckily many times and my parents try to help me in any way they can, working and getting good grades is very difficult. It doesn't give me life. (Rocío, non-traditional student, health sciences, Catalonia).

The percentage of students who receive some type of scholarship or study aid is higher among traditional students (73%) than among non-traditional students (64%). However, there are no differences in this regard between men and women.

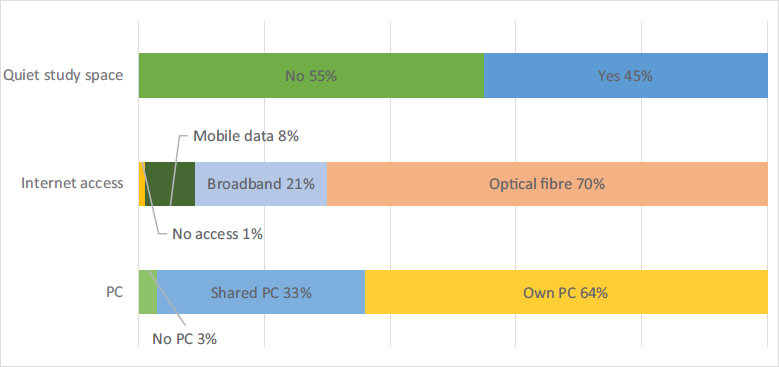

The analysis of the resources for study in the participants' homes also yields interesting results, even more so considering that the initial survey was carried out between May and June 2020, i.e. in the period in which universities moved all their academic activity to online format as a result of the measures adopted to deal with the COVID19 pandemic. Specifically, more than half of the students (55%) did not have a quiet study space, 33% did not have a computer for individual use and 3% did not have a computer at home. About internet connection, 8% only had mobile data and 1% did not have access to the internet.

GRAPH VIII. Scholarships/Grants by sex and student profile (%)

Source: compiled by the authors.

GRAPH IX. Study Resources (%)

Source: compiled by the authors.

The growing importance of virtual academic activity that has been experienced in recent years and that was especially manifested as a result of the measures related to the pandemic, moving a large part of university education to virtual or hybrid formats, has meant greater importance of technological resources and space for the monitoring of studies. The effects of this situation have been especially reflected in the most vulnerable populations and the increase in the educational gap concerning the majority population.

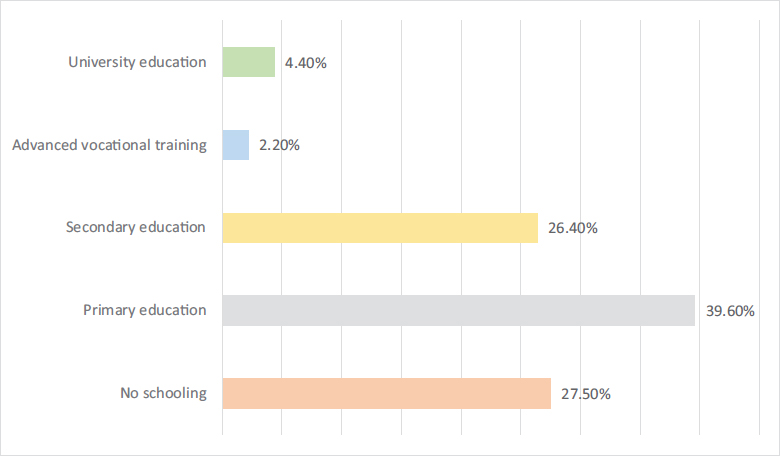

The study of the presence of ethnic minorities in universities is often approached in connection with first-generation students, i.e., those who are the first in their families to reach higher education. In cultural groups with little academic tradition, it is common for the majority of students to be first-generation, which constitutes a double source of discrimination and difficulty in the academic career.

GRAPH X. Family education level1 (%)

Source: compiled by the authors.

This is the case of the university Roma population, as reflected in the family educational level of the people who have participated in the study. Specifically, the quantitative fieldwork shows that 67% of the families have a maximum of primary education, 26% secondary, 2% higher education, and only 4% of the cases have one of the parents who has university studies.

My parents have, let's say, basic education, they don't have a high school diploma and so on, and they didn't make it to higher education and I'm the first of my siblings. So, the first time I enter university... (Rosa, traditional student, social sciences and humanities, Andalusia).

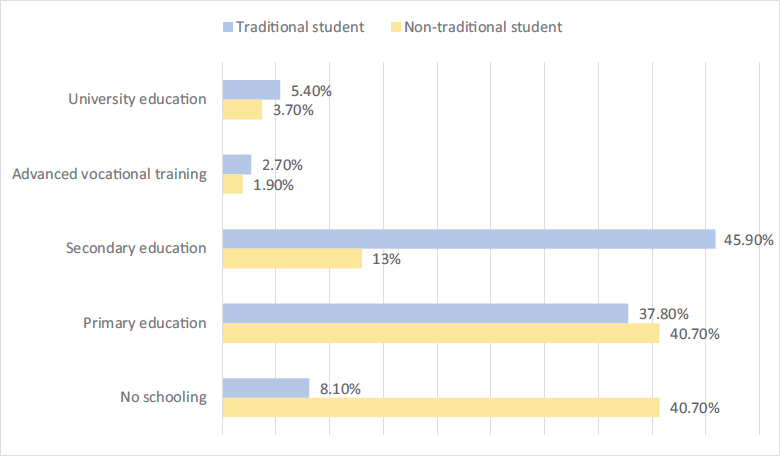

If we look at the differences according to the student profile, we find that the family educational level of traditional students is higher than that of non-traditional students.

GRAPH XI. Family educational level according to student profile (%)

Source: compiled by the author.

Often, this profile of students perceives great difficulty in facing university education and has basic academic deficiencies that drag from previous years and are detrimental to them today.

Well, the first years were quite complicated for me, especially the first because I didn't know how to do the O with a joint in the educational sense. I hadn't studied for 15 years and no matter how long I had been preparing to enter university for 2 years, I had a very low level or at least that's how I felt. (Juan, non-traditional student, social sciences and humanities, Catalonia).

In addition, they notice a greater difficulty in working as a team and organizing study (distributing time, following the rhythm of the class, etc.).

At first, it was complicated for me, for example, I didn't know how to do group work. They met by the drive and I didn't know how to do it. The way to look for information to do the work, the bibliography, and all this.... I had no idea how to do it. The organization to study did cost me a lot. (Rocío, non-traditional student, health sciences, Catalonia).

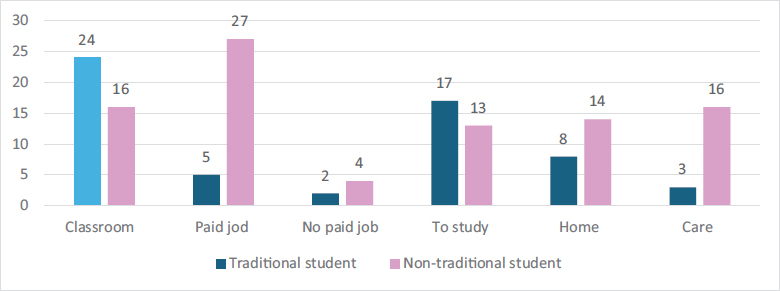

The academic dedication of Roma students, as with ethnic minority and first-generation students, is strongly influenced by the need to balance studies with other responsibilities, such as work and family. The analysis of the participants' time distribution patterns particularly reflects this aspect among non-traditional students. Students generally attend class for approximately 19 hours per week. However, there are significant differences between the groups (24 hours for traditional students and 16 hours for non-traditional students). The same is true for hours spent on independent study and academic work, with an overall average of 15 hours per week, but a difference of 4 hours between groups (17 hours for traditional and 13 hours for non-traditional groups).

Data shows that this group of students spends a significant amount of time on both paid work (18 hours) and household responsibilities (12 hours) and caring for others (10 hours).

There is also a marked difference between traditional and non-traditional students in their dedication to studies versus their dedication to other responsibilities, with averages of 5 hours, 8 hours, and 3 hours for the former, compared to 27 hours, 14 hours, and 16 hours for the latter.

TABLE II. Dedication in hours to academic tasks and other responsibilities (%)

Class |

Paid Work |

Voluntary work |

Study |

Home |

Care |

|

0h |

9% |

29% |

57% |

1% |

10% |

44% |

1-9h |

13% |

11% |

33% |

36% |

55% |

27% |

10am-7pm |

28% |

18% |

9% |

34% |

16% |

5% |

20-29h |

30% |

8% |

1% |

21% |

7% |

11% |

30-39h |

13% |

23% |

0% |

4% |

2% |

1% |

- 40 O+ |

6% |

11% |

0% |

4% |

9% |

11% |

MIDWEEK |

7 p.m. |

6 p.m. |

3 hours |

3 p.m. |

12 p.m. |

10 a.m. |

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XII. Average per week dedicated to various activities (hours) by student profile

Source: compiled by the author.

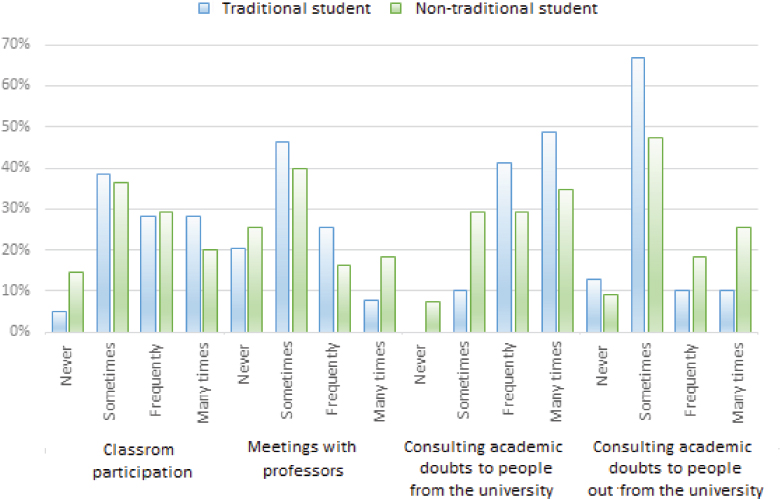

Another aspect analyzed about the university experience of Roma students shows that they tend to be participatory in the academic environment. The vast majority of them have participated in class and have attended tutorials at least once during the course in which the data were obtained. In addition, it is common for them to seek to resolve their academic doubts both with their classmates professors, and even with people outside the university.

Classification according to profiles reveals certain disparities in the forms of participation. For example, traditional students are more active in class discussions, while non-traditional students tend to attend tutorials more. We also observed that traditional students tend to raise their doubts more frequently with people within the university, while non-traditional students tend to seek answers through the help of people outside the institution.

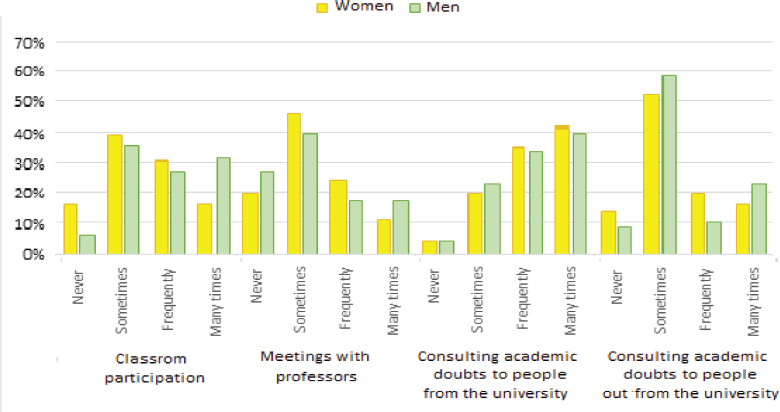

Although the distribution by sex is quite similar, the results show differences about classroom interventions, with male students being more likely than girls to do so.

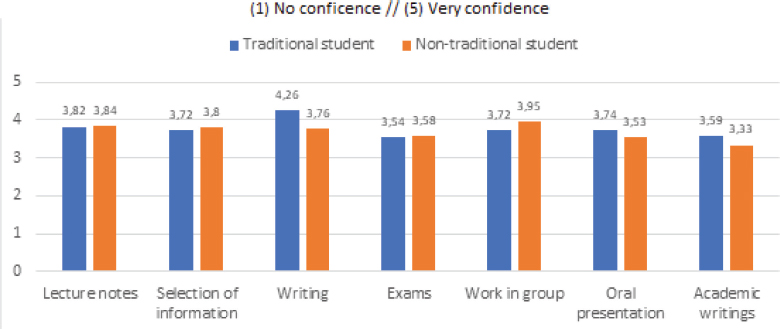

The scientific literature documents that students belonging to ethnic minorities, especially those with non-academic trajectories and who entered university late, tend to have low confidence in their abilities to perform academic activities (Chaney, 2018; Wong, 2018). However, the results of our study seem to contradict this perception, as the interviewees show high confidence in most of the academic aspects considered. In all cases, the average ratings exceed 3 out of 5.

GRAPH XIII. The frequency with which they have carried out, in the last year, various activities, by student profile (%)

Source: compiled by the author.

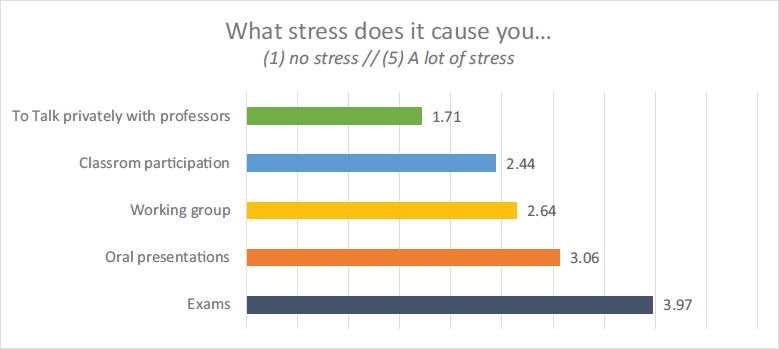

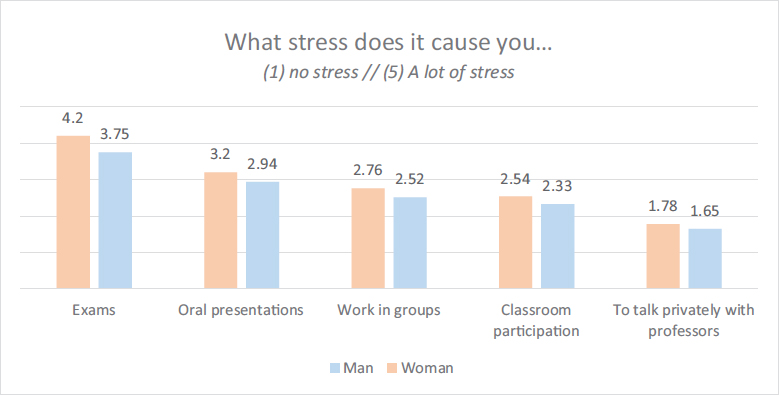

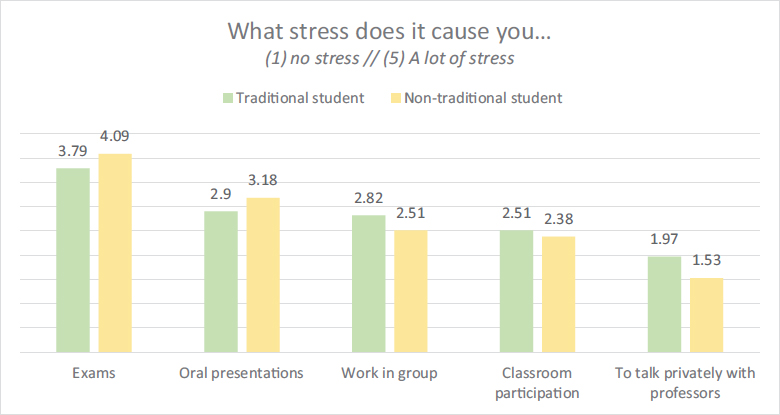

As for the stress perceived in the face of common academic situations, such as taking an exam or an oral presentation, the results show that what generates the most stress is the taking of exams, with an average of almost 4 out of 5. At a considerable distance, we find oral presentations, followed by group work, intervention in class, and talking privately with the teachers.

The analysis by sex indicates that the academic activities examined generate a significantly higher degree of stress among women. However, the results do not show notable differences between the two student profiles.

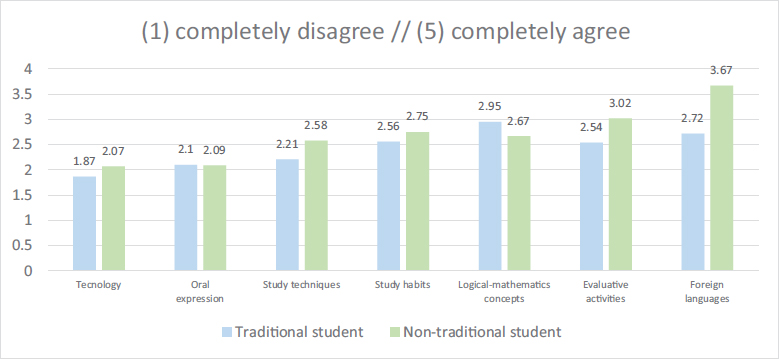

According to the students' perception, the academic competence that represents the greatest difficulty it would be the mastery of foreign languages. This aspect is a great challenge, especially for non-traditional students, taking into account that the fact of not having followed continuous school trajectories has made it difficult to achieve a level of English adequate to the current requirements of higher education in the international context. Concerning the perceived difficulty of logical-mathematical concepts, greater variability is contemplated. For example, students who study for degrees in subjects that require this type of skills point to it as a major difficulty. However, this same aspect is shown to be lacking among those students who study degrees where logical-mathematical skills are not required. In addition, participants perceive the need to further develop study techniques and habits. And speaking and technology are seen as less problematic.

GRAPH XIV. Frequency with which they have carried out, in the last year, various activities, by sex (%)

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XV. Academic confidence by student profile

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XVI. Stress in academic situations

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XVII. Stress in academic situations due to sex

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XVIII. Stress in academic situations by student profile

Source: compiled by the author.

GRAPH XIX. Academic difficulties by student profile

Source: compiled by the author.

The study shows the intersectionality of various factors of inequality that fall on Roma University students. Specifically, ethnic discrimination can be combined with discrimination based on sex and often with other variables related to the fact that they are mostly first-generation students, adult students, and those of disadvantaged socioeconomic status. Belonging more frequently to a profile of non-traditional students entails in many cases the need to combine studies with work and/or family obligations. Students perceive that the university is excessively rigid and is designed exclusively for traditional students, giving rise to the coping of great difficulties for those who are outside the traditional model. At the same time, the fact that they have frequently had discontinuous educational trajectories introduces specific difficulties related to training gaps in some learning that have been gaining importance in the field of education in recent years, such as mastery of the English language and the use of technologies, or the competent development of study techniques.

In relation to the socio-economic position of the Roma community in Spain, we find that many of them have insufficient material resources. This is manifested in the dependence on scholarships and the need to work to pay for studies. The insufficiency of resources for study may include aspects such as the lack of a workspace, good internet connection, or computer for one's own use, aspects that have been of greater relevance in recent years, due to the shift to online or hybrid formats as a result of the measures adopted to deal with the pandemic.

Historically, estimates of the Roma population in Spain have been obtained through specific fieldwork (Ruiz, 2009). In this way, the scarcity of documentary sources and the lack of an official population census make it difficult to obtain real knowledge of the Roma population in Spain through empirical procedures. However, the limitations in generating a sampling reference framework for the Roma population and, specifically, in identifying Roma university students, were addressed following the indications of psychosocial research to access hard-to-reach populations (Raifman et al. 2022). Consequently, we used snowball sampling to contact Roma University students through Roma associations and social networks, fulfilling the objective of identifying the sociodemographic and academic characteristics of Roma University students in an initial exploratory approach.

Discrimination against ethnic minority groups is a reality from which the university is not exempt. Specifically, the Roma people are the group that arouses the greatest rejection in our society, above other highly stigmatized groups. As a consequence, the multiplicity of barriers from different origins analyzed in the UNIROMA project is experienced by Roma students in a higher proportion than the average, due to the situation of social exclusion in which the Roma community finds itself. Specifically, Roma students experience some type of discrimination throughout their university career, which together with other difficulties associated with the scarcity of resources and the need to combine studies with other activities, can make it difficult to complete their studies.

The Roma University community has a non-traditional profile in a high proportion. In this way, other axes of inequality that operate in the university framework, such as age or social class, are added to ethnic discrimination. The risk of dropping out of university studies increases when the variables of sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, first-generation, and non-traditional profile intersect. Therefore, the results show the need to carry out actions that guarantee the permanence of Roma students, the vast majority of whom are first-generation, to complete higher education. The UNIROMA project has developed evidence-based recommendations to contribute to this goal. However, future research is required to continue to provide knowledge to improve the situation of Roma students and the institutional barriers they face in higher education.

This article adds relevant and significant information on the underrepresentation of first-generation students and/or students belonging to ethnic minorities in Spanish universities and specifically on graduation rates, aspects that are also of concern at the international level. To graduate, these students require comprehensive support through mentoring, academic and economic support, guidance, and promotion of their participation and link with the university, to conclude their studies.

The lack of representation of Roma students in higher education is explained by historical and structural inequality that requires social responsibility on the part of governments and higher education institutions. Aspects to take into account are the lack of familiarity with the university environment and the devastating effects of lacking a sense of belonging. Minority and first-generation university and university graduates are role models for the rest of the community, as they inspire and encourage future students (Aiello et al., 2019). Incorporating their voices to improve policies allows them to better identify the difficulties they experience, but it also helps to get information to new generations of university students. Thus, the first Roma to complete a university degree are very important references for their people and it is an aspect that the actions to be carried out in universities must take into account.

The scarcity of knowledge and information about the situation of the Roma people in Spain and Europe, both for teachers and for administration and services staff, makes it difficult to accompany Roma students. Training actions that respond to this lack and improve the representation of the Roma community at the university among the teaching staff can help Roma students connect with the institution and create a bond.

We thank all the members of the research team (Silvia Abad Merino, Jelen Amador, Ainhoa Flecha, Tania García, Sonia Garcia Segura, Ana Giménez, Fernando Macías, Paz Peña, Blas Segovia, Marta Soler, Teresa Sordé.) as well as the members of the Advisory Council (KAMIRA Federation, CAMPUSROM, Santiago Guerrero, Antonio Madrid, Itxaso Tellado, Ramon Vílchez, Rafael Santiago, Aaron Giménez, Jesús Martínez, Loli Santiago, Sara Santiago) and all the students who have contributed with their experience in this project. This study has been funded by the State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation 2017-2020 of the Ministry of Science, Research and Universities, with co-financing from the Structural Funds of the European Union. (Reference RTI2018-097879-A-100).

Agencia de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea (EU-FRA). (2016). Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey (EU-MIDIS II) Roma – Selected Findings. Vienna: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. https://doi.org/10.2811/469

Agencia de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea (EU-FRA). (2022). Roma in 10 European Countries. Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2022-roma-survey-2021-main-results2_en.pdf.

Aiello, E., Amador-López, J., Munté-Pascual, A. & Sordé-Martí, T. (2019). Grassroots Roma Women Organizing for Social Change: A Study of the Impact of ‘Roma Women Student Gatherings’. Sustainability, 11, 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154054

Alexiadou, N. (2019). Framing education policies and transitions of Roma students in Europe.Comparative Education,55(3), 422-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2019.1619334

Allaire, F. S. (2019). Navigating uncharted waters: First-generation native Hawaiian college students in STEM.Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 21(3), 305-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025117707955

Amnesty International & European Roma Rights Center. (2017). A Lesson in Discrimination: Segregation of Romani Children in Primary Education in Slovakia. Recuperado de http://www.errc.org/uploads/upload_en/file/report-lesson-in-discrimination-english.pdf

Arday, J. & Mirza, H. S. (Eds.). (2018). Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonizing the academy. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60261-5

Bîrle, D., Crişan, D., Bonchiş, E., Bochiş, L., & Popa, C. (2014). Roma Social Inclusion through Higher Education Policies in Romania. En F. Ribeiro, Y. Politis y B. Culum (Eds.), New Voices in Higher Education Research and Scholarship (pp. 213-231). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-7244-4.ch011

Brüggemann, C. (2014). Romani culture and academic success: arguments against the belief in a contradiction. Intercultural Education, 25(6), 439-452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2014.990229

Brüggemann, C. & D’Arcy, K. (2017). Contexts that discriminate: International perspectives on the education of Roma students.Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(5), 575-578. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1191741

Cashman, L. (2017). New label no progress: Institutional racism and the persistent segregation of Romani students in the Czech Republic.Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(5), 595-608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1191698

Center for Postsecondary Research (2019). NSSE (National Survey of Students’ Engagement) Modules. Recuperado de: https://nsse.indiana.edu/html/topical_module_participation.cfm [Consultado el 18 de marzo de 2019].

Chaney, I. (2018). Confidence in Ability: The Non-Traditional University Student. In 11th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, 12-14 November 2018 (pp. 7206-7211).

Comisión Europea. (2010). Europe 2020: A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.

Comisión Europea. (2020). A Union of Equity: EU Roma strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation for 2020-2030.

CREATES. (2010). Gypsies: from flea markets to school and from high school to the future. Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica. Publications Center. Ministry of Education.

De la Rica, S., Gorjón, L., Miller, L., & Úbeda, P. (2019). Comparative study on the situation of the Roma population in Spain concerning employment and poverty. FSG. Retrieved from https://iseak.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Estudio-comparado-sobre-la-situación-de-la-población-gitana-en-España-en-relación-al-empleo-y-la-pobreza.pdf

Flecha, A., Abad-Merino, S., Macías-Aranda, F. & Segovia-Aguilar, B. (2022). Roma University Students in Spain: Who Are They? Education Sciences, 12(6), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060400

Flecha, R. (2018). Learning communities and social transformation. Educators: Journal of Pedagogical Renewal, 265, 44-54.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). (2016). Exploring the Diversity of NEETs. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2806/62307

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2022). Roma in 10 European Countries. Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2022-roma-survey-2021-main-results2_en.pdf

Garaz, S. & S. Torotcoi (2017). Increasing access to higher education and the reproduction of social inequalities: The case of Roma University students in eastern and southeastern Europe. European Education, 49(1), 10-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2017.1280334

Gargallo, B., Jesús, S. R., & Pérez-Pérez, C. (2009). The CEVEAPEU questionnaire. An instrument for the evaluation of the learning strategies of university students. RELIEF. Electronic Journal of Educational Research and Evaluation, 15(2), 1-31.

Gómez, A., Racionero, S. & Sordé, T. (2010). Ten years of critical communicative methodology. International Review of Qualitative Research, 3(1), 17-43.

Harris, J. C. & Linder, C. (2018). The racialized experiences of students of color in higher education and student affairs graduate preparation programs.Journal of College Student Development, 59(2), 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0014.

Hinton-Smith, T., Danvers, E. & Jovanovic, T. (2017). Roma women’s higher education participation: whose responsibility? Gender and Education, 38(7), 811–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1274386.

Hinton-Smith, T. & Padilla-Carmona, M. T. (2021). Roma university students in Spain and Central and Eastern Europe: Exploring participation and identity in contrasting international contexts. European Journal of Education, 56(3), 454-467. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12459.

Kamberi, E., Martinovic, B. & Verkuyten, M. (2015). Life satisfaction and happiness among the Roma in Central and southeastern Europe. Social Indicators Research, 124(1), 199-220.

Kende, A., Hadarics, M., Bigazzi, S., Boza, M., Kunst, J. R., Lantos, N. A., Lášticová, B., Minescu, A., Pivetti, M. & Urbiola, A. (2020). The last acceptable prejudice in Europe? Anti-Gypsyism as the obstacle to Roma inclusion. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220907701.

Kundu, A. (2019). Understanding college “Burnout” from a social perspective: Reigniting the agency of low-income racial minority strivers towards achievement.Urban Review, 51, 667-698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00501-w.

Lambrev, V. (2020). ‘They clip our wings’: studying achievement and racialization through a Roma perspective. Intercultural Education, 31(2), 139-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2019.1702292.

Lens, D., & Levrau, F. (2020). Can pre-entry characteristics account for the ethnic attainment gap? An analysis of a Flemish university. Research in Higher Education, 61(1), 26-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11162-019-09554-Y.

Marcu, S. (2020). Mobility as a learning tool: educational experiences among Eastern European Roma undergraduates in the European Union, Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(6), 858-874. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2019.1579179.

Márquez, J.L. & Ordaz, M. (2014). Psychopedagogical characterization of the university student. Questionnaire for admission. Congreso Universidad. Vol. III, No. 2, 1-14, ISSN: 2306-918X.

McDonagh, C., & Fonseca, J. (2022). The minority within the minority: The survival strategies of Gypsy and Traveler students in Higher Education. International Journal of Roma Studies, 4(2), 150-171. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijrs.10344.

Messing, V. (2017). Differentiation in the making: Consequences of school segregation of Roma in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia. European Education, 49(1), 89-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2017.1280336.

Ministry of Social Rights and Agenda 2030. (2021). National Strategy for Equality, Inclusion and Participation of the Roma Population in Spain 2021-2030. Retrieved from https://www.mdsocialesa2030.gob.es/derechos-sociales/poblacion-gitana/docs/estrategia_nacional/Estrategia_nacional_21_30/estrategia_aprobada_com.pdf.

Mulcahy, E., Baars, S., Bowen-Viner, K., & Menzies, L. (2017). The underrepresentation of Gypsy, Roma, and Traveler pupils in higher education. A report on barriers from early years to secondary and beyond. King’s College London. Recuperado de https://www.lkmco.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/KINGWIDE_28494_proof3.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2024). Nontraditional Undergraduates/Highlights. Recuperado de: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs/web/97578a.asp.

Neumann, E. (2016). ‘Fast and violent integration’: school desegregation in a Hungarian town, Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(5), 579-594. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1191696.

OCDE (2020). Population with tertiary education (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/0b8f90e9.

Ogunyemi, D., Clare, C., Astudillo, Y. M., Marseille, M., Manu, E. & Kim, S. (2019). Microaggressions in the learning environment: A systematic review.Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13(2), 97-119. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000107.

Parra Toro, I., Álvarez-Roldán, A. & Gamella, J. F. (2017). A Silenced Conflict: Segregation Processes, Curricular Gaps and Dropout among Spanish Gitanos or Cale. Revista de paz y conflictos, 10(1), 35-60. https://doi.org/10.30827/revpaz.v10i1.5965.

Raifman, S., DeVost, M.A., Digitale, J.C. et al. (2022). Respondent-Driven Sampling: a Sampling Method for Hard-to-Reach Populations and Beyond. Curr Epidemiol Rep, 9, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-022-00287-8

Richardson, J. T. E. (2018). Understanding the under-attainment of ethnic minority students in UK higher education: The known knowns and the known unknowns. En Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonizing the academy (pp. 87-102). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60261-5_5.

Roberts, P. (2021). Class dismissed: international mobility, doctoral researchers, and (Roma) ethnicity as a proxy for social class? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(1), 142-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1855569.

Ruiz, J. S. (2009). Origins, vicissitudes, current reality, and challenges of the Roma people in Spain and the Region of Murcia. In Annals of Contemporary History, 25, 115-131.

Rutigliano, A. (2020). Inclusion of Roma students in Europe: A literature review and examples of policy initiatives.OECD Education Working Paper No. 228. Recuperado de https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/inclusion-of-roma-students-in-europe_8ce7d6eb-en

Salamońska, J. & Czeranowska, O. (2018). How to research multiple migrants? Introducing web-based respondent-driven sampling survey, CMR Working Papers, No. 110/168, University of Warsaw, Centre of Migration Research (CMR), Warsaw

Schanze J.-L. & Zins S. (2019). Undercoverage of the elderly institutionalized population: The risk of biased estimates and the potentials of weighting. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. Recuperado de: https://surveyinsights.org/?p=11275 [Consultado del 11 de marzo de 2019]

Serradell, O., García-Cabrera, M. M., Barrera-Rodríguez, M. F., & Ramírez, C. (2022). Recommendations for the support of Roma students at the University. International Journal of Roma Studies, 4(1), 172-203. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijrs.10682.

Silver, B. R. (2019). On the margins of college life: The experiences of racial and ethnic minority men in the extracurriculum. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 49(2), 147-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241619869808.

Slobodnikova, A. & Randolph-Seng, B. (2021). The effects of stereotype threat on Roma academic performance in Slovakia: role of academic self-efficacy and social identity. Journal for Multicultural Education, 15(2), 152-167. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-08-2020-0080.

Students for Education Reform (2017). First Generation College Survey. Recuperado de: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/sfer/pages/5254/attachments/original/1494530447/FGCS_Poll_5-11-17.pdf?1494530447 [Consultado el 18 de marzo de 2019]

The Velux Foundations (2019), “Education”, in 2019: Roma in Europe.

Times Higher Education – World University Rankings (2018). Student Experience Survey – Methodology. Recuperado de: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/student-experience-survey-2018-methodology [Consultado el 18 de marzo de 2019]

Urbiola, A., Navas, M., Carmona, C. et al. (2022). Social Class also Matters: The Effects of Social Class, Ethnicity, and their Interaction on Prejudice and Discrimination Toward Roma. Race and Social Problems, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-022-09368-1

Wong, B. (2018). By Chance or by Plan?: The Academic Success of Nontraditional Students in Higher Education. AERA Open, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858418782195

Želinský, T. (2022). Stereotype threat among European Roma adults. Applied Economics Letters, 29(1), 49-52, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2020.1855301

Contact information: Fernando Macías Aranda. Passeig de la Vall d'Hebrón, 171. Despacho 217. 2a planta. Edifici Llevant. 08035 Barcelona. E-mail: fernandomacias@ub.edu

_______________________________

1 To determine the family educational level, in each case, that of the parent with a higher level of education has been taken.