Hint strategies in educational escape rooms: a process mining approach

Estrategias de pistas en escape rooms educativas: un enfoque de minería de procesos

https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2024-405-626

Alexandra Santamaría Urbieta

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0935-0616

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja

Sonsoles López-Pernas

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9621-1392

University of Eastern Finland

Abstract

Educational escape rooms have become a useful tool for teachers who want to engage their students and attract their attention to the content taught. Also, they have been found to be valuable in improving learner outcomes, perceptions, and engagement in higher education. Although much attention has been placed on students’ opinions when playing educational escape rooms, not much attention has been placed on the importance of the design process, and little research has investigated the effectiveness of hint strategies in optimizing participant experiences and learning outcomes. In this study, and through a process mining approach, the hints strategies of four online educational escape rooms at the university level are determined.

The games were designed with the software Escapp, which allows researchers to collect students’ trace log data during the escape rooms. With this data, we calculated descriptive statistics for each escape room, studied the relationship between hints and performance, and to take into account the temporal aspect of students’ actions, we employed process mining to investigate the transitions between actions and the role of hints in helping students solve the puzzles. Results show that the use of hints was generally low and that participants relied more on their own problem-solving skills. However, there were instances in which hints were requested and correlated with longer gameplay duration and a higher number of failed attempts. In conclusion, the present study addresses a gap in the existing literature which highlights, after our analysis, the need for careful consideration of hint design and delivery strategies.

Keywords: educational escape rooms, hints, game-based learning, learning analytics, process mining.

Resumen

Los escape rooms educativos se han convertido en una herramienta útil para los profesores que quieren implicar a sus alumnos y atraer su atención hacia los contenidos impartidos. Además, se ha descubierto que son valiosas para mejorar los resultados, las percepciones y el compromiso de los alumnos en la enseñanza superior. Aunque se ha prestado mucha atención a las opiniones de los estudiantes acerca de estas metodologías educativas, no se ha atendido a la importancia del proceso de diseño, y se ha investigado poco sobre la eficacia de las estrategias de pistas que se deben diseñar para optimizar las experiencias de los participantes y los resultados de aprendizaje. En este estudio, y a través de un enfoque de minería de procesos, se determinaron las estrategias de pistas de cuatro escape rooms educativos online implementados a nivel universitario. Los resultados muestran que, en general, el uso de pistas fue escaso y que los participantes confiaron más en sus propias habilidades para resolver problemas. Sin embargo, hubo casos en los que se solicitaron pistas y esto se relacionó con una mayor duración del juego y un mayor número de intentos fallidos. En conclusión, el presente estudio aborda una laguna en la bibliografía existente que pone de relieve, tras nuestro análisis, la necesidad de considerar cuidadosamente el diseño de las pistas y las estrategias de diseño del juego. Los juegos se diseñaron con el software Escapp que permite a los investigadores recopilar los datos de registro de las pistas de los estudiantes durante el juego. Con estos datos, calculamos estadísticas descriptivas para cada escape room, investigamos la relación entre las pistas y el desempeño en el escape room y, para tener en cuenta el aspecto temporal de las acciones de los estudiantes, empleamos la técnica de minería de procesos con el objetivo de investigar las transiciones entre acciones y el papel de las pistas a la hora de ayudar a los estudiantes a resolver los desafíos.

Palabras clave: escape rooms educativos, pistas, aprendizaje basado en juegos, analíticas de aprendizaje, minería de procesos.

Introduction

Game-based approaches in education are far from game-over by any stretch of the imagination but rather a sequel that has been replicated in academia in different formats among various levels of education, subjects, and groupings. From STEM education (Wang et al., 2022), pharmacy education (Abdul Rahim et al., 2022) or nursing (Chang et al., 2021) to sex education (von Kotzebue et al., 2022) and professional upskilling (Tay et al., 2022). An increasingly popular game-based technique is the use of educational escape rooms, which have experienced an evolution at different levels, not only from the point of view of their design and implementation but also from the perspective of research. What simply started as questionnaires that examined students’ perceptions (Adams et al., 2018) after the implementation of an escape room in the classroom using qualitative analysis has now evolved to incorporate more complex quantitative analyses (López-Pernas et al., 2019a, 2022). Scholars use these in a bid to examine educational escape rooms’ learning effectiveness (López-Pernas et al., 2019a) with the use of more complex research techniques such as those of sequence and process mining (Vartiainen et al., 2022), or the combination of pre-tests, post-tests, and learning analytics (López-Pernas et al., 2022). Numerous studies have delved into the efficacy of educational escape rooms as a tool for imparting knowledge to students. However, there has been insufficient investigation about students’ actions, choices, and interactions with the game, which, as stated by these authors, calls for more complex methodological approaches for tracing patterns followed by players throughout the game (Vartiainen et al., 2022).

One of the main choices students have to make when playing educational escape rooms is whether or not to ask for help, which is often done by asking for hints. The hint strategy is paramount in educational escape rooms as it is quite “common for a team of students to get stuck while trying to solve a puzzle” (Gordillo et al., 2020, p. 225036). Thus, game designers should provide assistance or guidance to players throughout the game. By examining when and how players ask for hints, we can better understand how these influence their performance in the activity. Thus, the primary objective of our research is to bridge the existing knowledge gap regarding the efficacy of hints during gameplay. We endeavor to investigate various aspects, such as whether students who utilize hints extensively experience a greater level of success and if hints indeed aid students in succeeding in the educational escape room. Our research aims to fill a gap in the study of gaming by providing detailed insights into the significance of hints. We strongly believe that analyzing these strategies can assist game developers in creating better educational escape rooms. Additionally, our study may also showcase how process mining techniques can be effective and contribute to more complex research in the field of educational escape rooms.

Based on the information gathered so far, the present study aims to analyze the hint strategy employed by 318 students from an online university when playing individually four different digital educational escape rooms (from four different study programs), and its relationship with performance. To do so, we take a descriptive approach through the methodology of process mining, which will enable us to examine gameplay data logs collected in the open-source web platform Escapp (López-Pernas et al., 2021) during the escape rooms to facilitate a better understanding of students’ hint strategy. The Research Questions (RQs) of this study will be as follows:

RQ1: To what extent do students make use of hints during educational escape rooms?

RQ2: What is the relationship between hint usage and performance in educational escape rooms?

RQ3: What role do hints take in the puzzle-solving process during educational escape rooms?

Theoretical Framework

Overview of Educational Escape Rooms

According to Spira (2017), it is unclear where escape rooms originated, but the first documented reference to them dates back to 2007 in Japan (Sánchez-Martín et al., 2020). Prior to this, the idea of escape rooms was shaped in the form of video games and was featured on UK TV shows like The Adventure Game and The Crystal Maze. Over time, they have undergone various changes. Initially, they were just video games and recreational activities where participants had to escape from a room, but for some time now, they have also been used in educational settings to teach or review content using game-like methods. Educational escape rooms have transformed over the years and have become forms of recreation that “have drawn the attention of educators due to their ability to foster teamwork, leadership, creative thinking, and communication in a way that is engaging for students” (López-Pernas et al., 2019b, p. 31723). Escape rooms have proliferated (Veldkamp et al., 2020b) in educational settings (both physical, virtual, and hybrid) and have been found to be valuable in improving learner outcomes, perceptions, and engagement, also in higher education (Morrell & Eukel, 2020; Morrell & Ball, 2020). Furthermore, the quests included in them have also evolved from solely escaping from a room (Veldkamp et al., 2020a; Santamaría Urbieta & Alcalde Peñalver, 2019) within a given time limit to including murder mysteries or helping create a cure (López-Pernas et al., 2019b).

The Hint Strategy: How Important Is It?

As mentioned previously, hints in the educational escape room are meant to give players a little nudge or clue that can aid them in solving a particular challenge or puzzle (Clarke et al., 2017), maintaining at all times the appropriate level of balance within the game between being too straightforward or too difficult. Hints are there to help players learn and improve their problem-solving abilities by guiding them rather than providing the answers outright. Additionally, hints also can prevent students from feeling frustrated while playing the game. In 2015, Nicholson outlined the different methods that escape room facilities use to provide hints. After his study of 175 escape room facilities from around the world, he determined that the most common strategy was to offer hints as players request them (42%), and the second most popular method was to allow players to request a set number of hints, with a time penalty imposed if they did so (23%).

A common hint strategy involves providing gradual hints, that is, students request a first clue, which ought to be vague or subtle, the next hint includes more specific guidance, and, finally, the hints thereafter continually become more explicit, providing clearer and more direct instructions. Another common strategy is the multiple-level system, which offers, for instance, three levels of assistance: mild hints, moderate hints, and direct hints. Players would be the ones choosing the level of the hint they require, which strikes a balance between seeking guidance and maintaining a sense of accomplishment.

The scenario for which the educational escape room is designed also determines the hint strategy the gamemaster will employ, as it is not the same to give students hints in a face-to-face classroom, in which they can give straightforward clues as students get stuck throughout the game (López-Pernas et al., 2021), as when the educational escape room has been designed for an online environment, where the hint strategy can highly determine whether students will continue and “escape the room”, or just leave the room after feeling frustrated. In both scenarios, manually providing hints “can become overwhelming or even impossible if the student-teacher ratio is high” (p. 38063); the same happens when the educational escape room has been designed to be played asynchronously, that is, without the direct assistance of the gamemaster (a.k.a., the teacher).

To create a personalized hint system for both face-to-face and virtual scenarios, the web platform Escapp (López-Pernas et al., 2021) simplifies the process. This has been the digital tool where the four teachers of the present study have hosted their educational escape rooms. It enables teachers to decide if students are permitted to ask for hints during the escape room and if they can receive hints for free or by successfully completing a quiz. Additionally, Escapp allows teachers to set a minimum interval between hints to prevent students from frequently asking for help. The hint strategy utilized, whether gradual or multi-level, is at the teacher's discretion.

Process Mining and its Application in Education

Educational process mining (EPM) is an emerging field in learning analytics and educational data mining (Bogarín et al., 2018; Ghazal et al., 2017; Sweta, 2021), which refers to the examination and identification of patterns and movements in the event records produced by educational settings (Romero et al., 2016). It originated in the field of business (van der Aalst et al., 2012) and has been demonstrated to be successfully applied to educational settings (Pechenizkiy et al., 2009) due to its ability to produce “clear visual representations of the whole process” studied (p. 280). Notably, several works have capitalized on process mining methods in the context of educational games since they enable researchers to account for the key role of temporality in educational games —as in any learning activity. For instance, Caballero-Hernández et al. (2023) used process mining for skill assessment according to students’ actions in an educational game about databases. Several works by Gómez et al. (2021a, 2021b) used sequence and process mining to investigate students’ sequences of actions and errors in a geometry game. Schaedler Uhlmann et al. (2018) applied process mining to player interactions to analyze decision-making in remote educational games.

It is worth noting that further research in this area would undoubtedly contribute to a better understanding of how students learn and interact with educational games, leading to the development of more effective educational tools and strategies. In our study, we leverage “Player Experience Modeling” (PEM) as a pivotal framework for gathering and analyzing data about player behaviors and interactions within games. As defined by Nikitin (2020), PEM encompasses a comprehensive approach to understanding the multifaceted experiences of players by employing three distinct methodological groups: (1) subjective, (2) objective, and (3) gameplay-based methods. Each method serves a unique purpose in capturing different aspects of player experience, vital for our investigation into the hint strategies of educational escape rooms. Firstly, the subjective method allows to capture players’ personal impressions and feedback, providing insight into the perceived difficulty and engagement levels of the hints. This method is instrumental in understanding the emotional and cognitive impact of hints on players, which is crucial for evaluating their effectiveness in educational contexts. Secondly, the objective method, which utilizes physiological parameters such as heart rate and eye tracking, offers a window into the players' unconscious responses to game hints. This data helps identify moments of heightened stress or confusion, indicating potential areas where the hint system may need adjustment to better support learning outcomes. Lastly, the gameplay-based method focuses on analyzing interactions with game objects and the game environment. By employing process mining techniques, as suggested by Nikitin (2020), we can systematically examine how players navigate hint strategies within the game, revealing patterns and strategies that contribute to effective learning through gameplay. Together, these methods provide a holistic view of the player experience, enabling us to tailor and optimize the hint strategy in educational escape rooms. The integration of subjective, objective, and gameplay-based data ensures a comprehensive analysis of game-player interaction, directly informing the design and implementation of more effective educational tools.

Methods

Context and participants

The context in which these escape rooms were designed and put into practice with students was within an Educational Innovation Project at Anonymized University. In this project, four teachers were selected to try out the Escapp platform (López-Pernas et al., 2021) during the years 2022/2023, not only as designers of the escape rooms but also as testers of the software. The teachers were chosen because of their prior experience designing escape rooms, though they had not used Escapp before, and because they covered a wide range of disciplines encompassing humanities, social sciences and scientific courses. Through an initial training workshop in which the project coordinator described how Escapp worked and how they could design their escape rooms with this software, teachers had to think about the narrative of their educational escape games, the missions and challenges they wanted to incorporate, and how and when they were going to launch their games with their students.

After a process of tutoring contemplated in the project and which allowed teachers to ask the coordinator any possible questions and doubts about the design process and execution, all four teachers were able to launch their escape games successfully asynchronously and synchronously among their students in the course year 2022/2023. As we have already mentioned, there were four teachers; two of them taught at the bachelor’s degree level, and the other two at master’s degree level. The table below summarizes the educational escape rooms' subjects, topics, numbers of missions, modality of the game, and hints created by each teacher. It's important to note that the teachers were not given any instructions on how to design the hint strategy for each game.

TABLE I. Context and design of the educational escape rooms

Subject |

Level |

Study |

Topic |

Modality |

Puzzles |

Hints |

Participants |

Spanish |

Bachelor’s Degree |

Translation and Interpreting |

Students need to find a potion to help the main character find a boyfriend who does not make many mistakes when writing in Spanish. |

Synchronous & Asynchronous |

8 |

2 hints per puzzle |

30 |

Consumers and their Behavior |

Master’s Degree |

Neuromarketing |

Students had to prepare for a future job post. |

Synchronous |

10 |

2 hints per puzzle |

14 |

Physics |

Bachelor’s Degree |

Physics |

Abstract (No narrative) |

Asynchronous |

11 |

1 hint per puzzle |

65 |

Learning & Personality Development |

Master’s Degree |

Teacher Education |

A teacher who is working at a school for the first time is trapped inside a school and will not be able to escape until she can solve a number of problems related to the school, the students, the parents and other workmates. |

Asynchronous |

5 |

1 hint per puzzle |

209 |

Source: Compiled by authors.

Data collection

Students’ trace log data collected during the escape rooms were downloaded from the Escapp platform for each of the four escape rooms. The log data records all the relevant actions that players perform within the Escapp platform during the activity. Each record contains an identifier for the player, a timestamp, an identifier of the current puzzle the player is working on, and the name of the action, namely;

- Solve puzzle: The player provides the right solution to a puzzle.

- Fail puzzle: The player provides an incorrect solution to a puzzle.

- Obtain hint: The player requests a hint (pooled from a preset set of hints created by the teacher).

Data analysis

We conducted the analysis using the R programming language. As a first step of our analysis, we used the psych R package to calculate descriptive statistics for each escape room, including the total number of students who participated in the escape room and how many completed the escape room successfully (solved all the puzzles). We also calculated the mean duration to complete each puzzle per player, the mean number of failed attempts, and the mean hints per puzzle and player (RQ1).

To give answer to RQ2, we used the rstatix and stats R packages to conduct a series of statistical tests to investigate the relationship between the number of hints requested and students’ performance in the escape room (whether they completed it and how long they took). We first conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing the number of hints between those who completed the escape room and those who did not. Then, we computed Spearman’s correlation between the number of hints requested and gameplay duration (for those who completed the escape room), as well as between the number of hints requested and the number of failed attempts to solve puzzles. We used the correlation coefficient (r) as a measure of effect size. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, the effect size is small when r is between 0.1 and 0.3; medium when r is between 0.3 and 0.5; and large when r is greater than or equal to 0.5.

To address our last RQ (RQ3), we took into account the temporal aspect of students’ actions —since time is a key aspect of escape rooms—, using process mining to investigate the transitions between actions and the role of hints in helping students solve the puzzles. We relied on the R package bupaverse (Janssenswillen et al., 2019) to create a process map of students’ actions in each escape room and to compute the transition rates.

Results

RQ1: To what extent do students make use of hints during educational escape rooms?

Table II shows the descriptive statistics of the four escape rooms. The success rate of the escape rooms (number of participants who completed the activity over the total number of participants) varies greatly, ranging from 23.3% to 100%. The average time taken to solve the escape room puzzles revolves around 7-8 min., except for the Physics escape room, in which the average is remarkably low (1.30 min.). The average number of wrong solutions provided for the puzzles ranged from very low (0.58) to quite high (4.70), which may indicate trial-and-error behavior. The number of hints requested was very low, with less than one hint on average per puzzle.

TABLE II. Descriptive statistics of the four escape rooms. N = Number of students who completed the escape room / number of participants (success rate). Duration = Time taken to solve each puzzle (mean and standard deviation). Failed attempts = Number of failed attempts to solve each puzzle (mean and standard deviation). Hints = Number of hints obtained (mean and standard deviation)

Escape room |

N |

Puzzle Duration (min.) |

Failed attempts |

Hints |

Spanish |

7/30 (23.3%) |

M = 8.59 (SD = 7.56) |

M = 4.70 (SD = 13.79) |

M = 0.24 (SD = 0.54) |

Marketing |

14/14 (100%) |

M = 7.73 (SD = 15.12) |

M = 2.77 (SD = 7.04) |

M = 0.23 (SD = 0.61) |

Physics |

58/65 (89.2%) |

M = 1.30 (SD = 1.77) |

M = 0.58 (SD = 1.21) |

M = 0.02 (SD = 0.13) |

Teacher Ed. |

92/209 (44%) |

M = 7.26 (SD = 6.85) |

M = 5.13 (SD = 9.39) |

M = 0.40 (SD = 0.57) |

Source: Compiled by authors.

RQ2: What is the relationship between hint usage and performance in educational escape rooms?

Table III shows the results of the statistical tests conducted to assess the relationship between hints and performance in the escape rooms. First, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed no statistically significant difference between the number of hints received for those who completed the escape room and those who did not, except for the Teacher Education escape room, in which there was a small albeit significant difference, where those who completed the escape room received on average more hints. For those who completed the escape room, there was a small although significant correlation between the number of hints and the time taken to complete the activity in two of the escape rooms (Physics and Teacher Education). Lastly, there was a medium to large and statistically significant correlation between the number of hints requested and the number of failed attempts to solve the escape room puzzles.

TABLE III. Relationship between hints and performance:

(I. Hints vs. Completed) Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing the number of hints between those who completed the escape room and those who did not (II. Hints vs. Duration) Spearman’s correlation between hints requested and gameplay duration (for those who completed the escape room) and (III. Hints vs. Failed attempts) Spearman’s correlation between hints requested and failed attempts to solve puzzles

|

Hints vs. Completed |

Hints vs. Duration |

Hints vs. Failed attempts |

|||

|

r |

p-value |

r |

p-value |

r |

p-value |

Spanish |

-0.12 |

0.54 |

0.45 |

0.31 |

0.60 |

0.00* |

Marketing † |

- |

- |

0.05 |

0.87 |

0.57 |

0.03* |

Physics |

-0.09 |

0.48 |

0.37 |

0.00* |

0.42 |

0.00* |

Teacher Ed. |

0.20 |

0.00* |

0.27 |

0.01* |

0.67 |

0.00* |

Note: Since all participants completed the Marketing escape room, no comparison can be made.

Source: Compiled by authors.

RQ3: What role do hints take in the puzzle-solving process during educational escape rooms?

The process maps paint a clearer picture of the temporality and interplay of the recorded gameplay events. The “Start” node indicates a player starting to work on a puzzle, and the “End” node that they cease to work on a puzzle, be it because they have solved it correctly or because the time is up. The remaining nodes represent the three events recorded during students’ gameplay and are annotated with the share of the total number of events they represent. An arrow between node A and node B represents a transition between event A and event B, and is annotated with the percentage that transition represents out of all the transitions with origin in node A.

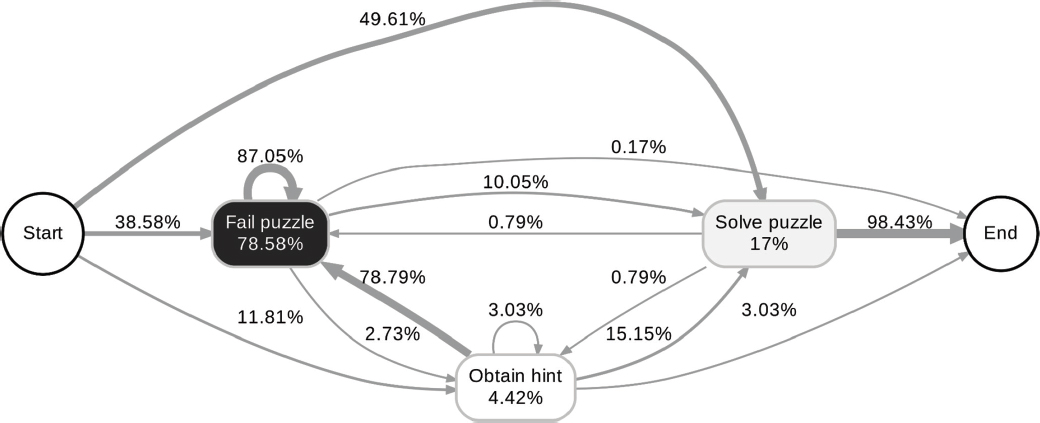

Figure I shows the process map of the Spanish language escape room. In almost half of the cases, students (49.61%) are able to reach the correct solution of a puzzle directly whereas, 38.58% of the times, students start by providing a wrong solution. Only 11.81% of the times students ask for a hint before attempting to solve the puzzle. Failed puzzle attempts often come in a row, since a failed attempt leads to another one 87.05% of the times. Only 11.81% of the times students resort to asking for a hint after providing a wrong solution to the puzzle. Moreover, hints lead to reaching the correct solution 15.15% of the times, and a wrong solution 78.79% of the times.

FIGURE I. Process map of the Spanish language educational escape room

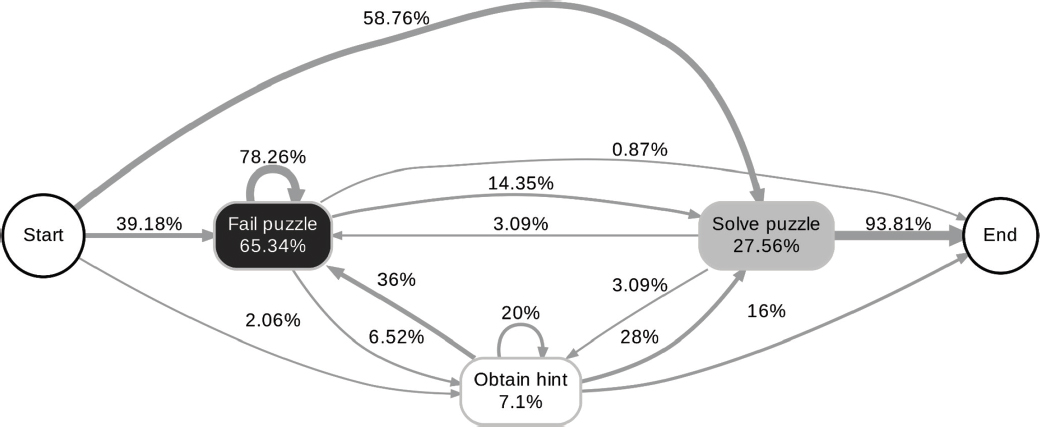

The Marketing educational escape room presents a similar scenario as the previous one with few yet important differences. In this escape room, requesting a hint leads to providing a wrong puzzle solution 36% of the times (half as in the previous escape room). Instead, students ask for subsequent hints (20%) or figure out the right puzzle solution straight away (28%).

FIGURE II. Process map of the Marketing educational escape room

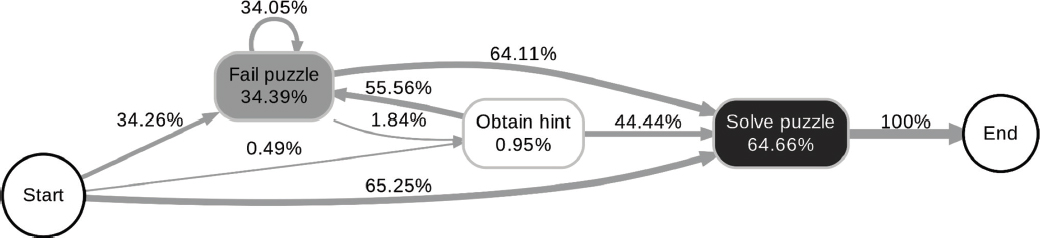

The Physics escape room seems to be the most straightforward, where students solve the puzzles on their first attempt 65.25% of the times. The role of hints in this escape room is almost non-existent (0.95% of all events) and their utility is not clear, as 55.56% of the occasions in which students ask for a hint, they are led to a wrong puzzle solution whereas 44.44% of the times they are led to the correct puzzle solution.

FIGURE III. Process map of the Physics educational escape room

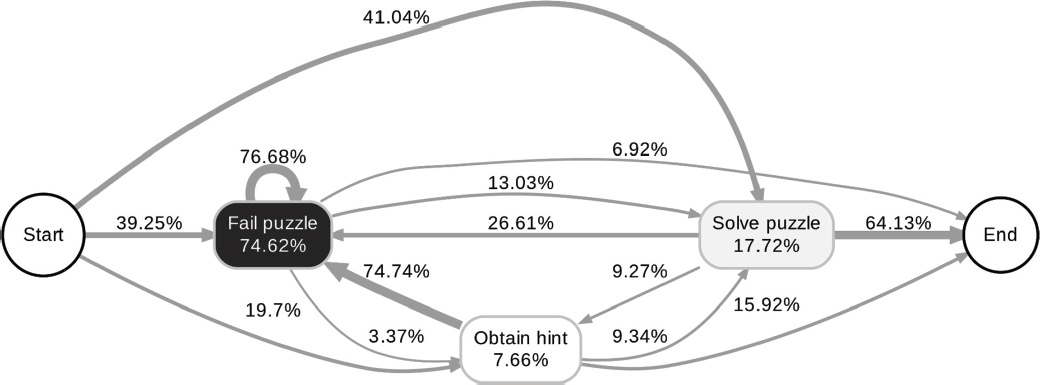

Lastly, the process map of the Teacher Education escape room is very similar to the Spanish language one, where students make several failed attempts to solve the puzzles and hints do not seem to be very effective in helping them overcome their difficulties.

FIGURE IV. Process map of the Teacher Education educational escape room

Discussion and Conclusions

The results obtained from the present study on hint strategies in educational escape rooms using a process mining approach reveal interesting insights into gameplay dynamics and the impact of hints on performance. In this section, we discuss the findings in relation to the research questions and highlight their implications for the design and implementation of educational escape rooms. Moreover, based on the results obtained, we suggest a hint strategy for the design of educational escape rooms.

The descriptive statistics presented in Table II provide a comprehensive overview of the four escape rooms analyzed in terms of success rate, puzzle duration, failed attempts, and hints obtained. One of the main conclusions obtained is that success rates vary significantly across the four escape rooms. The Spanish language escape room exhibits the lowest success rate, indicating that participants faced more challenges in this particular room. On the other hand, the Marketing escape room demonstrates the highest success rate, suggesting that it may have been relatively easier for participants to solve the puzzles. The average time taken to solve the puzzles aligns closely within the 7-8 minute range, except for the Physics escape room where participants remarkably completed the puzzles in an average time of 1.30 minutes. This notable difference in duration may reflect the low level of complexity and difficulty associated with the Physics escape room puzzles compared to the others since, for instance, the Marketing escape room had a similar number of puzzles but the mean duration to solve each puzzle was substantially higher. Additionally, the average number of wrong solutions provided for the puzzles varied, ranging from low to relatively high values, which may indicate trial-and-error behavior in some instances. Interestingly, participants requested a very low number of hints, with less than one hint on average per puzzle across all escape rooms.

Table III presents the results of the statistical tests conducted to explore the relationship between hints and performance in the escape rooms. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test reveals that, except for the Teacher Education escape room, there was no significant difference in the number of hints received between participants who completed the escape room and those who did not. This finding suggests that the availability of hints did not strongly influence participants' completion rates, except in the case of the Teacher Education escape room, where those who completed the room received, on average, more hints compared to those who did not complete it.

Furthermore, the correlations between the number of hints and gameplay duration indicate a small but significant relationship in two escape rooms: Physics and Teacher Education. This suggests that participants who requested more hints tended to spend more time on the puzzles in these specific escape rooms. This could be attributed to the complexity or ambiguity of the puzzles, where additional hints were required to guide participants towards the correct solution. The correlation analysis also reveals a significant and medium to large positive correlation between the number of hints requested and the number of failed attempts to solve the puzzles across all escape rooms. This implies that participants who sought more hints generally struggled with solving the puzzles and made a higher number of unsuccessful attempts.

The process maps depicted in Figures I to IV visually represent the temporal flow and interaction of events during gameplay in each escape room. These maps offer valuable insights into the patterns of puzzle-solving behavior and the role of hints in guiding participants. In a Spanish escape room, most participants tried a different approach before seeking help. Only a few asked for hints after giving a wrong answer, but the hints weren't very effective in leading to the correct solution. The Marketing escape room had a similar pattern to the Spanish language escape room, with some participants arriving at the correct solution and others starting with an incorrect solution. In this room, hints were slightly more effective, leading to the correct solution in 28% of cases. Interestingly, participants asked for subsequent hints more often than in the Spanish language escape room, indicating they relied more on hints when they faced challenges.

In contrast, the Physics escape room demonstrated a more straightforward puzzle-solving process, with participants achieving success on their first attempt in the majority of cases, probably due to the lack of difficulty of the puzzles designed. However, hints were not very helpful in this room and only accounted for 0.95% of all events. They seem to have caused more harm than good as they led to a wrong solution in the majority of cases instead of guiding participants to the correct solution.

Finally, the process map of the Teacher Education escape room resembled the pattern observed in the Spanish language escape room, with participants making multiple failed attempts to solve the puzzles. Hints were requested and utilized similarly to the Spanish language escape room, but their overall effectiveness in helping participants overcome challenges appeared limited.

The findings from the process maps highlight the importance of considering the sequence and impact of events in escape room gameplay. Understanding how participants approach puzzles, the timing of hint requests, and the outcomes of those hints can inform the design and delivery of educational escape rooms. These insights can be utilized to optimize the difficulty level and progression of puzzles, improve the efficacy of hints, and enhance the overall learning experience.

Data suggests that hint utilization in the educational escape rooms was generally low, with participants relying more on their own problem-solving abilities. However, there were instances where hints were requested and correlated with longer gameplay duration and a higher number of failed attempts. In fact, the process maps confirmed that, on many occasions, hints misled participants to the wrong puzzle solutions rather than helping them. This highlights the need for careful consideration of hint design and delivery strategies to optimize their effectiveness in facilitating successful puzzle-solving while maintaining an appropriate level of challenge. The variations in success rates and puzzle durations across the escape rooms further emphasize the importance of aligning the difficulty levels of puzzles with the target audience and learning objectives.

Our analysis has provided us with valuable insights that we can use to create a hint strategy, which should be understood as an approximation to enhance the effectiveness of hints in guiding participants towards successful puzzle-solving, while maintaining an optimal level of challenge and engagement.

- Gradual Hint Strategy. Implementing a gradual hint strategy that provides escalating levels of assistance is recommended. We encourage designers to start with subtle hints or clues that nudge participants in the right direction without explicitly giving away the solution. Following this approach, our results show that students needed few hints and therefore, disclosing too much information initially might prevent them from reaching the solution by themselves.

- Contextualized Hints. Tailor hints to the specific escape room theme and content, that is, incorporate hints that are relevant to the subject matter or concept being explored in the escape room.

- Timely Availability of Hints. Based on our analysis, we can conclude that providing hints to players can be helpful if we monitor their progress and strategically offer hints to prevent frustration and encourage ongoing engagement. The software Escapp, used in this study, allows us to determine when students can request hints and the appropriate time interval between each. We should point out that if the escape room is conducted online, the use of time-limited hints may reduce interest in the game and lead to dropout.

- Adaptive Hint System. This strategy would be interesting to integrate into a piece of software like Escapp, based on our results. As it has been observed, participants may consistently provide incorrect solutions or make many failed attempts. To avoid this, it would be interesting that the software incorporated an adaptive hint strategy to adjust the level of assistance based on participants’ performance and request patterns. Conversely, if students were progressing without much assistance, the hint strategy could adapt itself to that situation and maintain an appropriate level of challenge, avoiding boredom.

- Hints as Learning Opportunities. Designers should think of hints as key elements of the game because they should be considered promoters of active learning and problem-solving skills. We strongly advise against providing direct answers, as hints can prompt students to reflect on their approach, reconsider their assumptions, or provide alternative strategies to explore. This fosters critical thinking and promotes a deeper understanding of the concept being taught in the educational escape rooms.

- Hint Accessibility. Ensure that hints are easily accessible to participants. The software Escapp makes the inclusion of hints throughout the game very straightforward and does not interrupt the flow of the gameplay. This accessibility helps participants find hints more easily and faster, and it also helps designers to put all the hints in one single location, making it easier for the designer to also include them in the game.

In conclusion, this study used a process mining approach to examine hint strategies in educational escape rooms. The results provided valuable insights into the relationship between hints and performance, the dynamics of puzzle-solving behavior, and the effectiveness of hints across different escape rooms. The findings suggest that the availability of hints did not significantly impact completion rates, except in one escape room where completing participants received more hints. The correlation analysis revealed that the number of hints requested was positively associated with gameplay duration and the number of failed attempts. The process maps further illuminated the temporal flow and interaction of events during gameplay, highlighting the varying patterns of puzzle-solving behavior and the role of hints in facilitating or hindering progress.

These findings contribute to the broader field of educational escape rooms by providing empirical evidence on the impact of hints on gameplay and offering insights into how hints can be effectively utilized to enhance the learning experience. Future research can build upon these findings by investigating additional factors that may influence hint utilization and examining the long-term effects of educational escape rooms on learning outcomes. Overall, this study sheds light on the importance of understanding hint strategies in educational escape rooms, which can ultimately inform the design of more engaging and effective learning experiences.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, the data collected by Escapp is limited to what happens within the platform (i.e., puzzle resolution and hint requests) and therefore may not fully reflect all of the students’ actions during the escape rooms (e.g., consulting learning materials, or talking to one another). Although the fact our data is unobtrusively and systematically collected provides an objective and non-invasive way of measuring students’ performance, complementing the log data with video observations and/or interviews could provide a more detailed picture of each student’s gameplay from a more qualitative perspective. More information about the study participants would also allow us to understand the factors that might cause some students to choose a certain hint strategy, for example, gender, degree, or a lack of sufficient prior knowledge to solve the escape room. Moreover, although our study encompasses escape rooms in a variety of academic disciplines, our sample is limited to a single institution and therefore the generalizability of our findings to other contexts needs further investigation. Nevertheless, our choice of process mining as an analytical tool frames our study as descriptive rather than making any inferences or generalizations.

Bibliographic references

Abdul Rahim, A. S., Abd Wahab, M. S., Ali, A. A., & Hanafiah, N. H. M. (2022). Educational escape rooms in pharmacy education: A narrative review. Pharmacy Education, 22(1), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.46542/pe.2022.221.540557

Adams, V., Burger, S., Crawford, K., & Setter, R. (2018). Can You Escape? Creating an Escape Room to Facilitate Active Learning. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 34, E1–E5. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000433

Bogarín, A., Cerezo, R., & Romero, C. (2018). A survey on educational process mining. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 8(1), e1230. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1230

Caballero-Hernández, J.A., Palomo-Duarte, M., Dodero, J. M., & Gaševic, D. (2023). Supporting Skill Assessment in Learning Experiences Based on Serious Games Through Process Mining Techniques, International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2023.05.002

Chang, C., Chung, M., & Yang, J. C. (2021). Facilitating nursing students' skill training in distance education via online game-based learning with the watch-summarize-question approach during the COVID-19 pandemic: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Education Today, 109, 105256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105256

Clarke, S., Peel, D., Arnab, S., Morini, L., Keegan, H., & Wood, O. (2017). EscapED: A Framework for Creating Educational Escape Rooms and Interactive Games to For Higher/Further Education. International Journal of Serious Games, 4(3), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v4i3.180

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge. NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Ghazal, M.A., Ibrahim, O., & Salama, M.A. (2017). Educational Process Mining: A Systematic Literature Review, 2017 European Conference on Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). https://doi.org/10.1109/EECS.2017.45

Gómez, M. J., Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A., Martínez, P. A., & Y. J. Kim (2021a). Applying learning analytics to detect sequences of actions and common errors in a geometry game. Sensors, 21(4), 1025. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21041025

Gómez, M. J., Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A., Martínez, P. A., & Y. J. Kim (2021b). Exploring the Affordances of Sequence Mining in Educational Games. Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM'20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1145/3434780.3436562

Gordillo, A., López-Fernández, D., López-Pernas, S., & Quemada, J. (2020). Evaluating an educational escape room conducted remotely for teaching software engineering. IEEE. 8, 225032–225051. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3044380

Janssenswillen, G., Depaire, B., Swennen, M., Jans, M. J., & Vanhoof, K. (2019). bupaR: Enabling Reproducible Business Process Analysis. Knowledge-Based Systems, Vol. 163, p. 1857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2018.10.018

López-Pernas, S., Gordillo, A., Barra, E., & Quemada, J. (2019a). Analyzing Learning Effectiveness and Students’ Perceptions of an Educational Escape Room in a Programming Course in Higher Education. IEEE Access. 7, 184221–184234. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2960312

López-Pernas, S., Gordillo, A., Barra, E., & Quemada, J. (2019b). Examining the Use of an Educational Escape Room for Teaching Programming in a Higher Education Setting, in IEEE Access, vol. 7, 31723–31737. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2902976

López-Pernas, S., Gordillo, A., Barra, E., & Quemada, J. (2021). Escapp: A web platform for conducting educational escape rooms. IEEE Access. 7, 184221–184234. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2960312

López-Pernas, S., Saqr, M., Gordillo, A., & Barra, E. (2022) A learning analytics perspective on educational escape rooms, Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2041045

Morrell, B. L. M., & Ball, H. M. (2020). Can You Escape Nursing School? Educational Escape Room in Nursing Education. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(3), 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.000000000000044

Morrell, B. L. M., & Eukel, H. N. (2020). Escape The Generational Gap: A Cardiovascular Escape Room for Nursing Education. The Journal of Nursing Education, 59(2), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200122-11

Nicholson, S. (2015). Peeking behind the locked door: A survey of escape room facilities. http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/erfacwhite.pdf

Nikitin, K. (2020). Educational Game Analysis Using Intention and Process Mining. Modeling and Analysis of Complex Systems and Processes - MACSPro’2020, October 22–24, 2020, Venice, Italy & Moscow, Russia.

Pechenizkiy, M., Trcka, N., Vasilyeva, E., van de Aalst, W., & De Bra, Paul. (2009). Process Mining Online Assessment Data. International Working Group on Educational Data Mining; International Working Group on Educational Data Mining. Available from: International Educational Data Mining Society (EDM).

Romero, C., Cerezo, R., Bogarín, A., & Sánchez-Santillán, M. (2016). Educational Process Mining. In S. ElAtia, D. Ipperciel & O.R. Zaïane (eds.), Data Mining and Learning Analytics. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118998205.ch1

Sánchez-Martín, J., Corrales-Serrano, M., Luque-Sendra, A., & Zamora-Polo, F. (2020). Exit for success. Gamifying science and technology for university students using escape-room. A preliminary approach. Heliyon, 6(7), e04340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04340

Santamaría Urbieta, A., & Alcalde Peñalver, E. (2019). Escaping from the English Classroom. Who will get out first?, Aloma Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de l’Eduació i de l’Esport, 37(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2019.37.2.83-92

Schaedler Uhlmann, T., Alves Portela Santos, E., & Mendes, L.A. (2018). Process Mining Applied to Player Interaction and Decision Taking Analysis in Educational Remote Games. In: Auer, M., Langmann, R. (eds) Smart Industry & Smart Education. REV 2018. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 47. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95678-7_47

Spira, D. (2017). A Quick History of Escape Rooms. Room Escape Artist. https://roomescapeartist.com/2017/01/15/a-quick-history-of-escape-rooms/

Sweta, S. (2021). Modern Approach to Educational Data Mining and Its Applications. Springer Nature.

Tay, J., Goh, Y. M., Safiena, S., & Bound, H. (2022). Designing digital game-based learning for professional upskilling: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 184, 104518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104518

Vartiainen, H., López-Pernas, S., Saqr, M., Kahila, J., Parkki, T., Tedre, M., & Valtonen, T. (2022). Mapping students’ temporal pathways in a computational thinking escape room. Proceedings of the Finnish Learning Analytics and Artificial Intelligence in Education Conference (FLAIEC22) (pp. 77–88). CEUR.

Veldkamp, A., Daemen, J., Teekens, S., Koelewijn, S., Knippels, M.-C.P.J., & van Joolingen, W.R. (2020a), Escape boxes: Bringing escape room experience into the classroom. Br J Educ Technol, 51, 1220–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12935

Veldkamp, A., van de Grint, L., Knippels, M.-C.P.J., & van Joolingen, W.R. (2020b). Escape Education: A Systematic Review on Escape Rooms in Education, Educational Research Review, 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100364

van der Aalst, W. et al. (2012). Process Mining Manifesto. In: Daniel, F., Barkaoui, K., Dustdar, S. (eds) Business Process Management Workshops. BPM 2011. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 99. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28108-2_19

von Kotzebue, L., Zumbach, J., & Brandlmayr, A. (2022). Digital Escape Rooms as Game-Based Learning Environments: A Study in Sex Education. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 6(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti6020008

Wang, L., Chen, B., Hwang, G., Guan, J., & Wang, Y. (2022). Effects of digital game-based STEM education on students’ learning achievement: A meta-analysis. International Journal of STEM Education, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-022-00344-0

Contact address: Alexandra Santamaría Urbieta. Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Área de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Calle de García Martín 21, 28224, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid. E-mail: alexandra.santamaria@unir.net