NAVIGATING NATIONAL IDENTITY AND EUROPEAN INTEGRATION: THE EVOLUTION OF SPANISH COMPETITION LAW IN THE EU LEGAL ORDER (2020-2024)[1]

NAVEGANDO ENTRE LA IDENTIDAD NACIONAL Y LA INTEGRACIÓN EUROPEA: LA EVOLUCIÓN DEL DERECHO DE LA COMPETENCIA EN ESPAÑA DENTRO DEL ORDENAMIENTO JURÍDICO DE LA UE (2020-2024)

NAVIGUER ENTRE L’IDENTITE NATIONALE ET L’INTEGRATION EUROPEENNE : L’EVOLUTION DU DROIT DE LA CONCURRENCE ESPAGNOL DANS L’ORDRE JURIDIQUE DE L’UE (2020-2024)

ABSTRACT

This article examines the evolution of Spanish competition law within the European Union legal framework during the transformative period of 2020-2024. The analysis reveals significant institutional and legislative developments that have shaped the relationship between Spanish and EU competition law. Key developments include the transposition of the ECN+ Directive through Royal Decree-Law 7/2021, which enhanced the CNMC’s investigative powers and strengthened the antitrust sanctions regime. The period witnessed substantial institutional changes, including the appointment of Cani Fernández as CNMC President and Teresa Ribera as EU Competition Commissioner. The CNMC demonstrated increased enforcement activity, particularly in digital markets with landmark cases such as Amazon/Apple Brandgating (EUR 194 million) and Booking.com (EUR 413 million record fine). The authority also intensified its focus on bid-rigging, exemplified by the Obra Civil 2 case imposing EUR 203.6 million in fines on major construction companies. Merger control enforcement showed unprecedented activity with numerous gun-jumping proceedings and commitment violation cases. The Spanish legal framework evolved through significant Court of Justice rulings, including the Spanish Goodwill saga that clarified State aid selectivity concepts. These developments demonstrate Spain’s distinctive approach to competition enforcement while maintaining alignment with EU legal principles.

Keywords: Derecho de la competencia; ayudas de Estado; derecho de la Unión Europea; Comisión Europea; CNMC.

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza la evolución del derecho de la competencia español dentro del marco jurídico de la Unión Europea durante el período transformador de 2020-2024. El análisis revela desarrollos institucionales y legislativos significativos que han moldeado la relación entre el derecho de competencia español y europeo. Los desarrollos clave incluyen la transposición de la Directiva ECN+ a través del Real Decreto-Ley 7/2021, que fortaleció los poderes de investigación de la CNMC y el régimen de sanciones antimonopolio. El período presenció cambios institucionales sustanciales, incluyendo el nombramiento de Cani Fernández como presidenta de la CNMC y Teresa Ribera como comisaria de Competencia de la UE. La CNMC demostró mayor actividad sancionadora, particularmente en mercados digitales con casos emblemáticos como Amazon/Apple Brandgating (194 millones EUR) y Booking.com (multa récord de 413 millones EUR). La autoridad también intensificó su enfoque en colusión en licitaciones, ejemplificado por el caso Obra Civil 2 que impuso 203,6 millones EUR en multas a grandes empresas constructoras. El control de concentraciones mostró actividad sin precedentes con numerosos procedimientos de gun-jumping y casos de violación de compromisos. El marco jurídico español evolucionó mediante sentencias significativas del Tribunal de Justicia, incluyendo la saga Spanish Goodwill que clarificó conceptos de selectividad en ayudas estatales. Estos desarrollos demuestran el enfoque distintivo de España en la aplicación de la competencia manteniendo la alineación con principios jurídicos europeos.

Palabras clave: Competition law; State aid; EU law; European Commission; CNMC.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine l’évolution du droit de la concurrence espagnol dans le cadre juridique de l’Union européenne durant la période transformatrice de 2020-2024. L’analyse révèle des développements institutionnels et législatifs significatifs qui ont façonné la relation entre le droit de la concurrence espagnol et européen. Les développements clés incluent la transposition de la Directive ECN+ par le Décret-loi royal 7/2021, qui a renforcé les pouvoirs d’enquête de la CNMC et le régime de sanctions antitrust. La période a témoigné de changements institutionnels substantiels, notamment la nomination de Cani Fernández comme Présidente de la CNMC et Teresa Ribera comme Commissaire européenne à la Concurrence. La CNMC a démontré une activité d’application accrue, particulièrement dans les marchés numériques avec des affaires emblématiques telles qu’Amazon/Apple Brandgating (194 millions EUR) et Booking.com (amende record de 413 millions EUR). L’autorité a également intensifié son attention sur les ententes dans les appels d’offres, exemplifiée par l’affaire Obra Civil 2 imposant 203,6 millions EUR d’amendes aux grandes entreprises de construction. Le contrôle des concentrations a montré une activité sans précédent avec de nombreuses procédures de gun-jumping et cas de violation d’engagements. Le cadre juridique espagnol a évolué grâce à des arrêts significatifs de la Cour de Justice, incluant la saga Spanish Goodwill qui a clarifié les concepts de sélectivité des aides d’État. Ces développements démontrent l’approche distinctive de l’Espagne en matière d’application de la concurrence tout en maintenant l’alignement avec les principes juridiques européens.

Mots clés: Droit de la concurrence; aides d’État; droit de l’Union européenne; Commission Européenne; CNMC.

I. INTRODUCTION[Up]

The past five years have marked a dynamic period for competition law and policy in Spain. The quinquennium offers a timely opportunity to take stock of the most significant developments, reflect on their implications, and consider the evolving relationship between Spanish and EU competition law.

While Spanish competition law has been deeply shaped by EU norms, it has also followed its own path—developing distinct features that contribute to the richness and complexity of the broader EU framework.

This paper highlights the key developments from 2020 to 2024 across seven core areas: general public law (see Section II below); digital (see Section III below); antitrust (see Section IV below); mergers (see Section V below); and state aid (see Section VI below). By surveying these domains, we aim to distil the main trends, assess the interplay between Spanish and EU law (see Sections II-VI), and offer some insights into what the next five years may hold (see Section VII below).

II. GENERAL PUBLIC LAW[Up]

Between 2020-2024, there were also important developments in the field of ‘general public law’, which directly concern Spanish competition law. Particularly, (i) the Court of Justice found that the CNMC is not a “court” within the meaning of Article 267 TFEU and thus cannot refer questions for a preliminary ruling, departing from previous case law as a result of the evolution of the CNMC’s institutional architecture (see point 1 below); (ii) the Court of Justice declared that the Spanish state’s liability regime for breaches of EU law is incompatible with the general principle of effectiveness, in line with previous case law that had found that certain requirements of the previous regime were incompatible with the general principle of equivalence (see point 2 below); and (iii) the Spanish Constitutional Court confirmed that Article 101 TFEU is a rule of public order in line with the Ecoswiss case law (see point 3 below).

1. The CNMC is not a “Court” under article 267 TFEU (ANESCO)[Up]

On September 16 2020, the Court of Justice declared inadmissible a request for a preliminary ruling submitted by the CNMC in the Anesco case[5]. (See also Hornkohl, 2020). The Court of Justice found that the CNMC did not qualify as a “court or tribunal” within the meaning of Article 267 TFEU because it did not fulfil the criteria laid down by the case law[6]. In particular, the Court of Justice found that the CNMC was “not called upon to give judgment in proceedings intended to lead to a decision of a judicial nature”[7].

The Court of Justice concluded that the proceedings before the CNMC and its decisions were of an administrative nature instead because:

-

—the CNMC acts ex officio as a specialized administration exercising the power to impose penalties in matters falling within its competence[8];

-

—the CNMC is required to work in close collaboration with the Commission and may be denied jurisdiction in favor of the latter[9];

-

—the CNMC may withdraw its decision if a party brings an action before the administrative courts and agrees to it[10];

-

—the CNMC’s decisions are not capable of acquiring force of res judicata [11] ; and

-

—the CNMC’s decisions are subject to appeal before an administrative court, where it appears as a defendant[12].

This interpretation was confirmed by Article 29(4) of the Law establishing the CNMC[13], which provides that a decision of its Board puts an end to the expressly-named “administrative” proceedings[14]. As a result, the proceedings before the CNMC “are on the periphery of the national court system” and the CNMC’s decisions are of an administrative nature, not judicial[15].

This finding contrasts with the 1992 ruling in Dirección General de Defensa de la Competencia v Asociación Española de Banca Privada and Others, where the Court of Justice did admit the request for a preliminary ruling from the CNMC[16]. The different outcome is explained by the evolution of the Spanish institutional framework. Back then, the Spanish Competition Authority encompassed a competition court separate from the investigative body, whereas today the investigation and decision-making functions are separated, but handled under the same administrative roof (i. e., within the CNMC).

2. The Court of Justice declares that the Spanish State liability regime for breaches of EU law is incompatible with the Principle of Effectiveness (Commission v Spain)[Up]

In June 2022, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice ruled that the Spanish state liability regime for breaches of EU law is incompatible with the general principle of effectiveness[17]. The judgment followed a series of complaints lodged by private individuals in 2016, which prompted the Commission to launch an infringement procedure against Spain under Article 258 TFEU in 2017. The pre-litigation phase ran until 2019, without Spain remedying the infringement or providing a satisfactory defense. The Commission thus brought the matter before the Court of Justice in 2020.

The Court examined the compatibility of the Spanish state liability regime for breaches of EU law, set out in Articles 32 and 34 of the Law on the Regime Governing the Public Sector[18] and Article 67 of the on the Common Administrative Procedure[19], with the general principles of effectiveness and equivalence. In essence, the Court found that four criteria required by the Spanish state liability regime were incompatible with the principle of effectiveness, namely that:

-

i.there be a judgment of the Court of Justice declaring that the applied rule with the status of law is incompatible with EU law (in line with Brasserie du Pêcheur [20]);

-

ii.the injured party has obtained, at any instance, a final judgment dismissing an appeal against the administrative act which caused the damage, thus excluding cases in which the damage derives directly from an act or omission of the legislature without there being a challengeable administrative act;

-

iii.a limitation period of one year from the publication in the EU Official Journal of the judgment of the Court of Justice declaring the incompatibility of said norm, thus excluding cases where there is no such declaratory judgment; and

-

iv.only damages occurring five years prior to the date of the publication in the EU Official Journal can be compensated, for the same reason[21].

On the other hand, the Court found that the Spanish state liability regime, insofar as it required claimants to demonstrate a “sufficiently serious breach” in damages actions against the state for breaches of EU law, but not in damages actions for breaches of the Spanish constitution, was not incompatible with the principle of equivalence (See further Iglesias, 2020).

The judgment follows another landmark ruling of the Grand Chamber, which declared that the Spanish state liability regime for breaches of EU law, as developed by the case law of the Spanish Supreme Court, was incompatible with the general principle of equivalence. In Transportes Urbanos, the Court took issue with the requirement that the claimant exhaust all domestic remedies in damages actions against the Spanish legislator for breaches of EU law, but not in damages actions for breaches of the Spanish constitution[22]. (See further Doménech-Pascual, 2021).

3. The Spanish Constitutional Court confirms that article 101 TFEU is a rule of public order (Cabify and Auro)[Up]

In a judgment rendered on December 2 2024, the Spanish Constitutional Court clarified that provisions of EU law declared as rules of public order by the Court of Justice in Ecoswiss [23] and its progeny—such as Article 101 TFEU—have the same consideration under the Spanish legal system, and that the misapplication of these rules in arbitration proceedings can constitute a ground for the annulment of the award[24]. (See Constitutional Court of Spain, 2016).

The case concerned Cabify and Auro, two companies active in the provision of transportation services. In February 2017, Auro agreed to provide its services exclusively through Cabify’s digital platform. Following a contractual dispute —regarding in particular the exclusivity clause— the parties submitted the matter to arbitration. In December 2020, the Court of Arbitration of Madrid ruled in favor of Auro, finding that the exclusivity clause constituted a restriction of competition by object and was therefore null and void. Cabify subsequently filed an action for annulment of the award before the Madrid Court of Appeal. The court upheld the claim, holding that the arbitral award assessed the dispute solely under the Spanish Competition Act, without applying Article 101 TFEU, a rule of public order[25].

On February 11 2022, Auro filed a recurso de amparo before the Spanish Constitutional Court, alleging that the Madrid Court of Appeal had violated its rights of defense by exceeding its jurisdiction in annulling the arbitral award. In its judgment, the Spanish Constitutional Court confirmed the principle that Article 101 TFEU constitutes a rule of public order under Spanish law, like any other EU law provision recognized as such by the Court of Justice. As a result, its misapplication may constitute one of the exceptional grounds for setting aside an award, in accordance with Article 41(1)(f) of the Spanish Arbitration Act[26].

However, the Spanish Constitutional Court also found that the arbitral tribunal had, in fact, considered the applicability of Article 101 TFEU and had assessed whether the agreement could benefit from the exemption provided under Art. 101(3) TFEU. Accordingly, the Spanish Constitutional Court concluded that the Madrid Court of Appeal had exceeded its jurisdiction in setting aside the award. As a result, it annulled the judgment of the Madrid Court of Appeal and ordered the issuance of a new award in compliance with Auro’s fundamental rights.

However, on March 24 2025, the Madrid Court of Appeal suspended the proceedings and referred a preliminary question to the Court of Justice, essentially asking whether the findings of the Spanish Constitutional Court are compatible with the principles of primacy, effectiveness, and unity of EU law[27].

III. DIGITAL MARKETS[Up]

As anticipated above, the past five years have also been marked by increasingly robust enforcement in the digital sector. The CNMC addressed, for the first time, vertical restrictions on online sales (see point 1 below) and closed a complaint against Amazon, Booking.com, and TripAdvisor concerning false reviews (see point 2 below). Even more notably, it imposed two of its highest-ever fines within the span of a single year on Amazon, Apple, and Booking.com (see points 3-4 below). The CNMC also opened infringement proceedings against Apple for a possible abuse of its dominant position in the distribution of applications for its devices (see point 5 below). Far from being an isolated trend, this enforcement reflects growing awareness of the need to ensure a competitive digital ecosystem, a shared objective that culminated in the adoption of the DMA in 2022 and the designation of the seven gatekeepers between 2023 and 2024.

1. The CNMC assessed for the first time vertical restrictions on online sales (Adidas)[Up]

The CNMC terminated proceedings with commitments in February 2020, establishing important precedents for vertical restrictions in digital markets[28]. The case established three key legal principles: (i) contractual clauses limiting sales to an authorized “point of sale” may constitute online sales prohibitions even without express regulation; (ii) restrictions on online advertising through search engines equivalent to online sales prohibitions constitute hardcore restrictions; and (iii) pre-authorization requirements for online sales or brand use in domain names constitute hardcore restrictions when defined abstractly, particularly without reasonable response timeframes. Such conduct is now classified as hardcore restrictions under Article 4(e) of the 2022 Vertical Block Exemption Regulation.

2. The CNMC closed a complaint against Amazon, Booking.com, and Tripadvisor over false reviews (opiniones falsas plataformas)[Up]

The CNMC closed its complaint against Amazon, Booking.com, and TripAdvisor in November 2023, finding insufficient evidence of Article 3 Spanish Competition Act violations[29]. The authority determined that false reviews were published by third parties, not attributable to platforms, and that all platforms had implemented reasonable measures to counteract false reviews. The case demonstrates the increasing interconnectedness between competition and consumer protection issues.

3. The CNMC fines apple and Amazon for restricting competition on Amazon’s website in Spain (Amazon/Apple Brandgating)[Up]

On July 12 2023, the CNMC fined Apple and Amazon in the region of EUR 194 million for including certain clauses in the contracts governing Amazon’s conditions as an Apple reseller, which effected the sale of Apple products on Amazon’s website in Spain[30]. In particular, the distribution agreement restricted competition from third-party resellers of Apple products as well as from sellers from competing products. Apple was fined EUR 164 million, making it the second highest fine ever imposed by the CNMC on a single company. The combined fine ranks as the CNMC’s third-largest overall, following the EUR 413 million fine on Booking.com in 2024 and the EUR 203.6 million fine on several construction companies in 2022 (see point 4 in this Section, and Section IV, point 1.2 below).

According to the CNMC, Apple and Amazon agreed to restrict the number of re-sellers of Apple products on Amazon’s website in Spain by allowing only a limited number of distributors pre-selected by Apple to sell these products (a practice known as the use of brand-gating clauses). The CNMC found that up to 90% of re-sellers that had previously used the Amazon website for the retail sale of Apple products were excluded from the main e-commerce platform in Spain. In addition, Apple and Amazon agreed to limit the visibility of competing products by restricting the advertising space on Amazon’s website in Spain (so-called advertising clauses). While Amazon’s standard search function typically displays results from competing brands, the CNMC found that Apple and Amazon had agreed that, when a user searched for “Apple”, only Apple products would be shown on the results page. Finally, Apple and Amazon agreed to restrict Amazon’s ability to conduct marketing campaigns targeting customers who had purchased Apple products on its website in Spain with promotions for competing brands, unless prior consent was obtained from Apple (“marketing limitation clauses”).

The Decision was appealed before the Spanish National Court (“Audiencia Nacional”), which temporarily suspended the payment of the fine for both Apple[31] and Amazon[32], pending final judgment.

4. The CNMC fined Booking.com for abusing its dominant position[Up]

The CNMC imposed a record EUR 413 million fine on Booking.com in July 2024 for abusing its dominant position in online hotel booking intermediation services. This represents the highest fine ever imposed by the CNMC on a single company[33] (see also CNMC, 2024a).

The authority found two types of abuse since January 2019. The exploitative abuse involved narrow parity clauses preventing Spanish hotels from offering better prices on their own websites while reserving Booking.com’s right to compete on price, subjecting hotels to Dutch law and courts, and providing insufficient information about premium programs. The exclusionary abuse centered on ranking manipulation, where Booking.com prominently ranked hotels performing well on its platform, restricting competitors’ market expansion.

The Decision imposed behavioral remedies and is currently under appeal to the Spanish National Court. The case raises alignment questions with the Digital Markets Act, as Booking.com is now designated as a gatekeeper and prevented from requiring parity conditions under Article 5(3) DMA. This creates potential jurisdictional complexity since the Commission has exclusive competence to interpret DMA provisions whilst the CNMC assessed the same conduct. On March 7, as part of the appeals proceedings, the National Court adopted an interim measure suspending the fine (El Mundo, 2025).

5. The CNMC probed Apple for possible anti-competitive conduct in the distribution of apps on its devices[Up]

On July 24 2024, the CNMC initiated infringement proceedings against Apple for a potential abuse of its dominant position in the market for distribution of applications for its devices (See CNMC, 2024b). According to the press release, Apple may have imposed unfair commercial conditions on developers distributing their applications through the App Store to users of Apple products. Although the press release does not detail the commercial conditions under investigation, previous investigations by the Commission suggest that they may relate to the imposition of anti-steering provisions on its app developers. For context, on March 4 2024, the Commission fined Apple over EUR 1.8 billion for imposing such provisions to music streaming app developers, preventing them from informing users of Apple products about alternative and cheaper music subscription services that were available outside the music app (see European Commission, 2024c)[34]. Apple was also investigated under the DMA for similar conduct. In particular, on March 25 2024, the Commission launched a non-compliance investigation under Article 5(4) DMA—which requires gatekeepers to allow app developers to communicate consumers offers outside the gatekeepers’ app stores, free of charge—and has since found Apple in breach of that provision and imposed a fine (see European Commission, 2025a)[35].

IV. ANTITRUST[Up]

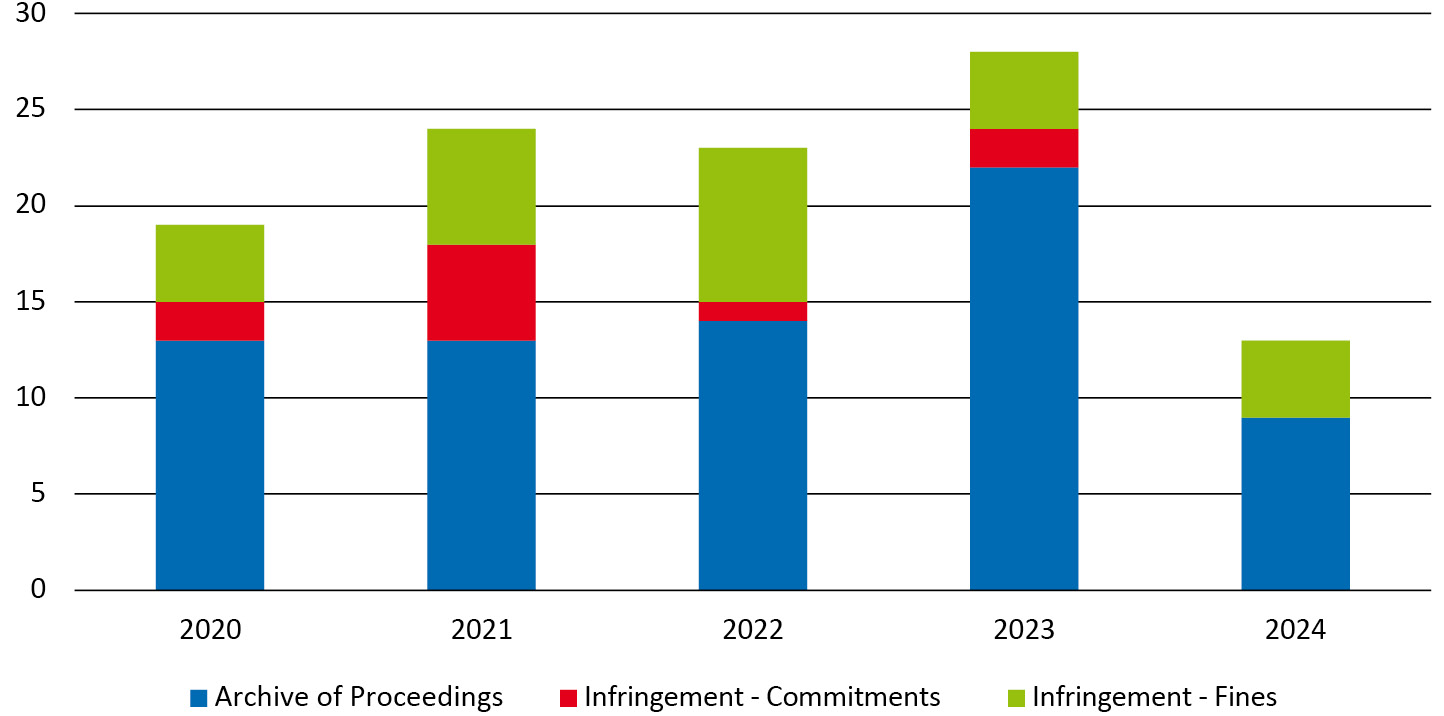

The CNMC has been actively engaged in antitrust enforcement over the past five years, issuing a total of 107 decisions, as shown in Figure 1 below. However, the majority of these decisions—71 in total, representing 66%—were closures of proceedings with no infringement found. In contrast, the CNMC identified antitrust infringements in 36 cases, accounting for 34% of all decisions. Of these, 10 were resolved through commitments from the involved parties, while the remaining 26 resulted in fines.

The five-year period can be divided into two distinct phases. The first half saw a clear upward trajectory in the number of antitrust decisions issued, culminating in a record 28 decisions in 2023. However, this number sharply decreased in 2024, with only 13 decisions, less than half the number from the previous year. From an enforcement perspective, 2021 was the most prolific year for the authority, with 11 infringement decisions (including both fines and commitments) and 13 closures of proceedings. In that year, infringement decisions accounted for 45% of all decisions, marking an 11-point increase over the five-year average of 34%.

Figure 1.

Number of Antitrust Decisions from the CNMC (2020-2024)

Source: Data sourced from the CNMC[36].

This section provides an overview of the CNMC’s ongoing efforts in antitrust enforcement. Point 1 highlights the CNMC’s intensified focus on bid-rigging probes, while point 2 addresses its enforcement practice against other anti-competitive agreements. In contrast, points 3 and 4 showcase the CNMC’s active pursuit of exploitative and exclusionary abuse cases, respectively. Taken together, these developments illustrate the CNMC’s comprehensive and persistent approach to tackling anti-competitive behavior.

1. Bid-rigging[Up]

The CNMC has remained focused on investigating bid-rigging practices, leading to some of the largest infringement decisions over the five-year period. During this time, the authority has developed its BRAVA (Bid Rigging Algorithm for Vigilance in Antitrust) platform, which utilizes algorithmic screening of public tenders (for further information, see CNMC, 2024c). This platform is now in its early stages of implementation, aiming to enhance the CNMC’s ability to detect and prevent anti-competitive behavior in public procurement.

1.1. The CNMC intensified bid-rigging probes[Up]

In particular, 2021 was a milestone in the CNMC’s probe into collusion in public tenders. The CNMC has previously scrutinized bid-rigging practices due to their substantial impact on public finances, but in 2021 the emphasis notably increased to 70% of all cartel sanctions: i. e., out of its 7 cartel sanctions, 5 were bid-rigging cases. To summarize, in early February 2021, the CNMC imposed a EUR 5.76 million fine on the participants of a bid-rigging cartel in the market for the supply of radiopharmaceutical fluorodeoxyglucose to hospitals[37]. In May 2021, the CNMC imposed a EUR 6 million fine on several consulting companies for colluding in local public tenders[38]. During the summer, the CNMC handed down two fines—EUR 1 million for cartels in the passenger transport sector[39], as well as an additional EUR 61 million fine in the road maintenance sector[40]. In October 2021, the most significant case was decided when the CNMC imposed a EUR 128 million fine on the main companies involved in the security, signaling, and communications systems for Spanish high-speed trains[41].

In most cases, the CNMC imposed the prohibition to contract with the Spanish public administration and fined executives. These measures, as well as the investigative role of the economic intelligence unit, have gained importance in the fight against collusion in public tenders since 2019. In 2020, the CNMC released an updated “Guide on public tenders and competition”, which contains recommendations to improve the design of public tenders and detect anti-competitive practices (CNMC, 2020). The CNMC’s commitment to combatting bid-rigging has been a cornerstone of the CNMC’s enforcement efforts in recent years, as demonstrated by the following developments.

1.2. The CNMC imposed record fine on six construction companies for decades-long bid-rigging practices (Obra Civil 2)[Up]

In July 2022, the CNMC fined six of the main construction companies in Spain (Acciona Construcción S. A., Dragados S. A., FCC Construcción, Ferrovial Construcción, Obrascón Huarte Lain S. A., and Sacyr Construcción S. A.) EUR 203.6 million for bid-rigging practices spanning more than 25 years[42]. The CNMC qualified the conduct as a very serious infringement of Article 1 of the Spanish Competition Act and Article 101 TFEU because it effected thousands of tenders organized by the Spanish public administration (mainly by the Ministry of Transport) concerning high-value contracts for the construction of key infrastructure, such as hospitals, ports, airports, and roads. The construction companies met weekly, starting in 1992, in order to analyze and distribute public tenders among them and exchange commercially sensitive information relating to technical aspects of the tenders and their bidding plans (though the authority found no evidence of exchanges of price information). The construction companies developed a sophisticated modus operandi governing the operation of the cartel that evolved over the duration of the infringement. At the time, the fine marked the highest ever imposed by the CNMC.

1.3. The CNMC fined four companies and six executives for bid-rigging up to 100 public contracts in the Defense sector (licitaciones material militar)[Up]

In 2023, the CNMC fined four companies in the defense sector (Comercial Hernando Moreno Cohemo, S. L. U., Star Defense Logistics & Engineering, S. L., Grupo de Ingeniería, Reconstrucción y Recambios, JPG, S. A., and Casli, S. A.) and six of their executives for colluding in tenders of the Ministry of Defense concerning the supply, maintenance, and modernization of military equipment[43]. The illicit agreements effected up to a 100 public contracts with a total value in the region of EUR 60 million, which mainly related to the maintenance of military vehicles and camping material. The sanctioned companies, along with the six executives, participated in a network of arrangements including non-compete agreements, coordinated bids, and formed temporary joint ventures to ensure access to the tenders on an equal footing. The CNMC fined the four companies EUR 6.2 million for two separate incidences, each constituting a single and continuous infringement of Article 1 of the Spanish Competition Act, and handed down fines to the six executives ranging from EUR 34,000 to 60,000. In addition, the CNMC imposed a ban on contracting with the public sector as foreseen under Article 71.1.b of Law 9/2017, of 8 November 2017, on Public Procurement on three of the four companies, subject to the State Public Procurement Advisory Board (“SPPAB”) determining the scope and duration of the ban. Nonetheless, the CNMC positively noted the implementation of ex post compliance programs and requested that the companies refer back on the developments of these within six months, based on which the CNMC would potentially ask the SPPAB to impose a pecuniary penalty only.

1.4. The CNMC launched an investigation into RENFE for alleged bid-rigging [44] [Up]

In July 2024, the CNMC announced that it had opened an investigation into RENFE, the State-owned national railway operator, for alleged bid-rigging. In 2022, Pecovasa—a RENFE subsidiary specializing in the rail transport of cars—launched a tender for the provision of traction services for its freight trains, which was later won by Renfe Mercancías, RENFE’s freight subsidiary. An association representing several privately-owned railway freight operators filed a complaint with CNMC. The authority carried out dawn-raids on both RENFE subsidiaries and their head company in October 2023.

This is just the latest in a series of run-ins between RENFE and competition authorities in recent years. In January 2024, the Commission accepted RENFE’s commitments in the online rail ticketing market, following a formal investigation into RENFE’s allegedly abusive behavior in the market[45].

2. Anti-competitive agreements[Up]

During the 2020-2024 period, there were relatively few major developments with regard to anti-competitive agreements. Notably, 2020 saw a significant development, with the Supreme Court upholding a 2016 CNMC Decision in the diaper cartel case, clarifying important aspects of the scope of antitrust liability (see point 2.1 below). This was in addition to Decisions involving digital markets, as covered in Section III above.

2.1. A cartel participant not active in the effected market is nevertheless liable[Up]

The Spanish Supreme Court established in May 2020 that cartel participants can be held liable even when operating in connected, rather than directly effected markets[46]. In the Textil Planas Oliveras case, the CNMC had fined the company EUR 800,000 for participating in an adult diapers cartel despite selling exclusively to hospitals rather than through pharmacies like other cartel members[47].

The Supreme Court overturned the National Court’s 2018 Decision annulling the CNMC fine, ruling that Article 101 TFEU contains no limitation restricting violations to undertakings operating only in effected markets. Following EU precedent from the Treuhand case[48], the Court emphasized that facilitator conduct directly linked to cartelists’ efforts, aimed at achieving anti-competitive objectives with full knowledge, constitutes a violation.

The key legal test focuses not on whether the participant derived an explicit benefit, but whether it facilitated collusion in any way, even indirectly. The Court noted that requiring direct market participation would create “a criterion of impunity”. This establishes the fundamental principle that when sanctioning anti-competitive behavior, “the starting point is the irrelevance of the market in which the parties operate”.

3. Exploitative abuses[Up]

The CNMC has experienced a rise in cases involving exploitative abuses, with several landmark decisions made during the 2020-2024 period. This shift underscores the authority’s increased attention on tackling practices that exploit consumers, such as unfair pricing and other forms of abusive conduct, across different industries. This aligns with the Commission’s own practice, which has been particularly active in addressing exploitative abuses in recent years, as evidenced by its recent Decisions in the Apple [49] and Meta [50] cases.

3.1. The CNMC brought Spain’s first case on “sham litigation” and misuse of patent procedures (Insud Pharma)[Up]

In October 2022, the CNMC imposed a hefty EUR 39 million fine, in addition to a prohibition to conclude contracts with the Spanish public administration, to the Spanish subsidiary of multinational pharmaceutical Merck Sharp & Dohme for abusing its market position in the market for the sale of vaginal contraceptive rings[51]. The CNMC found that the company had resorted to “sham litigation” and misused patent procedures in order to delay and suppress competition from new entrants.

Merck, which had enjoyed a 15-year monopoly over the sale of its contraceptive Nuvaring, invoked its patent rights against an alternative contraceptive launched in June 2017—less than a year from the expiry of its patent—and requested a Barcelona court to issue an ex parte suspension order to stop the manufacture and sale of Insud Pharma’s product. This relief was granted in September 2017, after Merck had alleged that its rival had failed to provide the necessary evidence to assess whether their patent had been breached. Upon finding that Merck had withheld relevant factual and technical information that would have challenged the basis of its legal actions—notably, Insud Pharma had indeed offered to provide the evidence to assess the existence of a patent infringement—the Barcelona court lifted the interim suspension in December 2017.

As a result of the suspension, however, Insud Pharma was forced to halt marketing, sale and production of its contraceptive until December 2017, effectively extending the dominance of Merck’s Nuvaring in the Spanish market and disrupting normal competitive dynamics. After a three-year long investigation, the CNMC concluded that Merck’s lack of transparency and legal action was not aimed at enforcing its patent rights, but rather at suppressing competition from new providers.

The authority followed the criteria defined by the EU Courts[52], as follows: (i) the legal action could not be considered as a reasonable attempt to assert the proprietary rights of Insud Pharma and therefore only served to harass the opposing party; and (ii) the legal action was part of a plan whose goal was to eliminate competition. The CNMC adopted the infringement decision shortly after the Commission sent Teva a Statement of Objections over its alleged misuse of patent procedures and alleged disparagement campaign to prolong the exclusivity of Copaxone (European Commission, 2020)[53]. The CNMC’s Decision also followed a series of national enforcement proceedings sanctioning disparaging conduct by pharmaceutical companies. For instance, since 2013, the French Competition Authority has sanctioned several pharmaceutical companies on anti-competitive disparagement grounds[54], and in 2014 the Italian Competition Authority adopted a Decision under Article 101 TFEU on similar grounds against Hoffman-La Roche[55].

3.2. The CNMC sanctioned Correos’ rebates (Correos 3)[Up]

In February 2022, the CNMC imposed a EUR 32 million fine on Correos, the Spanish public postal operator, over its rebate practices. Correos, which enjoys a quasi-monopolist position in the Spanish market (e. g., in some of the years examined by the CNMC, Correos’ relevant market shares were over 95%), was found to have abused its dominant position through a system of conditional and retroactive discounts for large business customers[56]. Notably, the CNMC concluded that, given the protracted duration of the contracts, the lack of transparency in the calculation of the discounts, and their non-standardized application, such conduct had the effect of preventing the entry of new competitors in the market for traditional postal services for large corporate customers.

3.3. The CNMC ended leadiant’s excessive pricing strategy[Up]

In November 2022, the CNMC imposed a EUR 10 million fine on the pharmaceutical company, Leadiant, the sole manufacturer of the drug for the treatment of cerobrotendinous xanthomatosis (“CTX”), a rare disease affecting around 50 patients in Spain, for abusing its position in the market for the sale of such drugs[57]. Leadiant had managed to secure its position as sole manufacturer of drugs based on chenodeoxycholic acid (“CDCA”) by negotiating an exclusivity agreement with the only supplier of the active ingredient authorized to supply CDCA at scale, and relaunching its medicine as an orphan drug, a status granted by the European Medicines Agency to drugs aimed at the treatment of rare diseases that confers a 10-year exclusive marketing right. The CNMC found that, since 2010, Leadiant had systematically increased the price of its drug from EUR 50 for a box of 100 capsules in 2010 to over EUR 14,000 in 2017. The authority concluded that such an increase could not be attributed to any additional risks or costs borne by the company, and thus the price charged as of 2017 was abusive in light of its disproportionate and unfair nature. In addition to the fine, the CNMC has imposed an obligation on Leadiant to (i) sell its drug in Spain at a non-excessive price negotiated with the Spanish Ministry of Health, and (ii) waive the exclusivity agreement with the sole supplier of the drug’s active ingredient.

3.4. SGAE’s “flat rates” are abusive[Up]

On June 26 2024, acting on a complaint filed by entities Derechos de Autor de Medios Audiovisuales, Entidad de Gestión (Dama), and Unison Rights, S.L. (Unison), the CNMC fined Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE) EUR 6.4 million for abusing its dominant position by designing “averaged availability rates” (comparable to a flat rate) for all radio and the large majority of television operators in order to use SGAE’s repertoire[58]. According to the CNMC, the SGAE’s flat rates constituted (i) an exploitative abuse, insofar they forced radio and television operators to pay excessive rates that were disconnected from the effective use of the repertoire, and (ii) an exclusionary abuse, insofar they discouraged radio and television operators from contracting with SGAE’s competitors. The CNMC found that, with regard to musical works, the exclusionary effect was reinforced by SGAE’s conduct of presenting its musical repertoire to users as universal and offering indemnity guarantees against possible claims by third parties for the use of rights not belonging to its repertoire.

4. Exclusionary abuses[Up]

Exclusionary abuses have received less attention from the CNMC in the past five years compared to exploitative practices. However, 2022 saw two significant Decisions addressing discriminatory practices. In Enel Green Power España (see point 4.1 below), the CNMC found that Enel, acting as a “Single Node Interlocutor”, abused its position by prioritizing its own access requests to the power network over competitors, distorting capacity allocation. Similarly, in Real Sociedad Canina de España (“RSCE”), the CNMC sanctioned the RSCE for using discriminatory fees, restricting judges, and enforcing exclusivity agreements to undermine rival canine associations. These national enforcement actions reflect broader EU trends, such as the European Super League case (see point 4.2 below), where the Court of Justice ruled against opaque and discriminatory access rules imposed by dominant market players acting as both regulators and participants.

4.1. The CNMC tackles discriminatory practices in Enel Green Power España and Real Sociedad Canina de España[Up]

The CNMC’s scrutiny extended to the market for the access and connection to the power network. In 2022, the CNMC took issue with Enel Green’s conduct as “Single Node Interlocutor” in two access points to the power network for renewable energy generation facilities (Enel Green Power España) [59]. In short, at the time of the abusive conduct, Spanish power regulation required the designation of a company as intermediary between Red Eléctrica Española (the Spanish Electricity Network operator) and other access seekers to the power network. The function of such intermediaries was to process access requests made to Red Eléctrica de España, a “decisive” step for the allocation of capacity among several requesters. The CNMC found that Enel Green, as “Single Node Interlocutor”, had abused its role in two nodes by prioritizing its own requests while unduly delaying the submission of requests from its competitors. Enel Green was thus able to gather more capacity than it would have normally been able to under normal competitive conditions and prevented rivals from accessing such capacity.

In another notable Decision in 2022, the CNMC found that the Spanish Royal Canine Society had abused its unique position in the markets for the genealogic certification of purebred dogs and the qualification of judges through a combination of discriminatory practices aimed at rival associations[60]. While pedigree certification was liberalized in 2001—and since then a number of alternative associations have emerged—the RSCE is the only body in Spain that can emit internationally recognized export certificates, and more than seven out of ten Spanish expert judges participating in competitions and exhibitions for purebred dogs are licensed by the RSCE. In these circumstances, the CNMC found that the RSCE had suppressed the expansion of rival associations and the success of their dog shows, competitions and exhibitions by (i) setting out discriminatory fee regimes and registration requirements for owners of dogs originally registered by rival associations, (ii) prosecuting, prohibiting, and sanctioning expert judges licensed by the RSCE participating or seeking to participate in events organized by rival Spanish dog associations, and (iii) creating a network of collaborating members and clubs through exclusivity and non-competition agreements, aimed at furthering the RSCE’s position.

4.2. The Madrid Commercial Court issued its ruling in European Super League [61] [Up]

The Madrid Commercial Court delivered its final judgment on May 24 2024 following the EU Court of Justice’s preliminary ruling[62], echoing the European Court’s findings that FIFA-UEFA’s pre-authorization rules violated EU competition law (see Pérez de Lamo et al., 2022). The Court of Justice had ruled on December 21 2023 that FIFA-UEFA’s rules were contrary to Articles 101 and 102 TFEU because the organizations held dominant positions whilst simultaneously regulating market access through non-transparent, discriminatory criteria with disproportionate sanctions[63].

Following the judgment, UEFA adopted new Authorisation Rules in June 2024[64], whilst A22 Sports Management relaunched the European Super League project as the “Unify League” in December 2024 (for additional information on A22, see A22, 2025). This case reflects broader EU enforcement trends against discriminatory practices by dominant sports organizations, consistent with precedents like the International Skating Union case.

V. MERGERS[Up]

1. Merger statistics[Up]

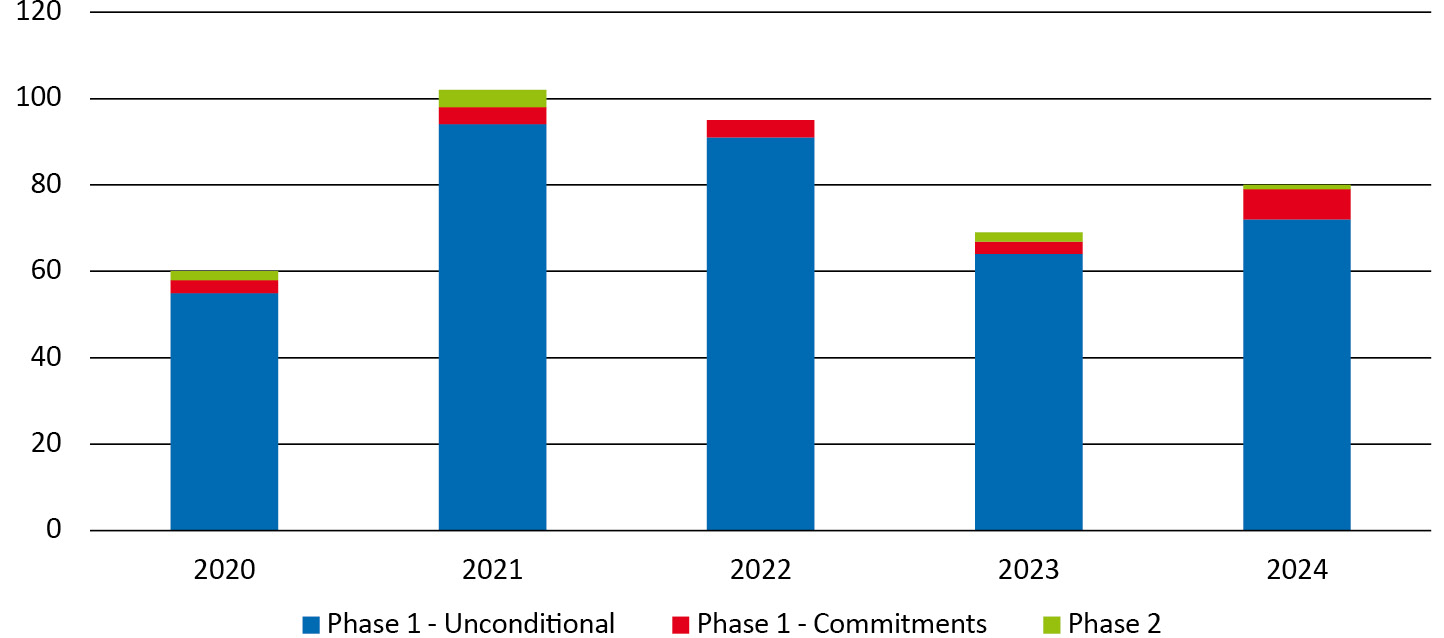

The pandemic-induced downturn in mergers and acquisitions in 2020 was followed by a surge in transactions in Spain, leading to record levels of transactions in 2021 and 2022. However, inflation and rising interest rates contributed to a decline in mergers and acquisitions throughout 2023. Despite this slowdown, a recovery began to take shape toward the end of 2024, suggesting a potential rebound in the market and a renewed flow of transactions in Spain, as seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Number of Merger Control Decisions from the CNMC (2020-2024)

Source: Data sourced from the CNMC (see CNMC Memorias 2020-2023)[65].

The highest number of merger decisions was recorded in 2021, with a total of 102, while 2020 saw the lowest number at just 60. In 2022, 2023, and 2024, the CNMC issued 95, 69, and 80 merger decisions, respectively.

The majority of these decisions were unconditional approvals, with the percentage consistently remaining well above 90%. Notably, 2022 saw a large number of clearances but no Phase 2 decisions, while 2024 experienced the smallest percentage of unconditional clearances, dropping to 90%.

In recent years, Spanish merger control has witnessed intensified activity, driven by a new wave of consolidation in the banking sector, increased involvement in EU-level referrals, and robust enforcement of procedural rules. The CNMC has reviewed major domestic mergers, such as Caixabank/Bankia and BBVA/Sabadell (see point 2 below), while also participating in Article 22 EUMR referrals, such as in Qualcomm/Autotalks (see point 3 below). In parallel, the authority has reinforced its oversight through infringement proceedings concerning gun-jumping, non-compliance with commitments, and, for the first time, misleading information in merger filings. These developments reflect a broader shift toward stricter scrutiny and more assertive merger enforcement in Spain.

2. Consolidation in the banking sector[Up]

The Spanish banking sector has undergone a new wave of consolidation, building upon the previous wave that occurred in the aftermath of the financial crisis, during which the number of players in the sector was drastically reduced. At the European level, authorities have consistently advocated for further consolidation within the sector (Reuters, 2024). This push is intended to enhance the global competitiveness of European banks and to reinforce the functioning of the common market, ensuring that the sector remains competitive and resilient in the face of international challenges.

One of the most relevant mergers in 2021 was the acquisition of Bankia by Caixabank, two major players in the Spanish banking sector. The transaction, involving the country’s third- and fourth-largest banks, respectively, created the single largest entity in Spain by domestic assets, ahead of BBVA and Santander. Santander, however, remains the leading Spanish bank in terms of global assets. The transaction forms part of a decade-long consolidation process in the sector, which has led to the near-complete disappearance of savings banks through successive mergers, acquisitions, and restructuring operations, ultimately reinforcing the position of the four largest commercial banks. For instance, prior to its acquisition by Caixabank, Bankia had itself been created through the merger of seven savings banks in 2010. In 2017, it further expanded by acquiring a rival that had also been formed in 2010 through the merger of four savings banks.

The transaction was notified in November 2020 and was cleared in Phase I in late March 2021, following the CNMC’s approval of commitments offered by the parties, which focused primarily on addressing local-level post-acquisition concerns[66]. In particular, the parties committed to (i) restricting the closure of branches in underserviced municipalities; (ii) maintaining their terms and conditions in areas where they held high market shares; and (iii) granting customers access to the acquirer’s closest ATMs where Bankia’s ATMs had shut down. Additional commitments included (iv) transparency in Caixabank’s communications with Bankia’s clients; (v) maintaining terms and conditions for vulnerable clients; and (vi) undertaking statutorily-mandated divestitures in stocks.

Though less noteworthy, in late June 2021, the CNMC cleared another merger in the banking sector between Unicaja and Liberbank, which resulted in the fifth-largest domestic bank in Spain[67]. As with Caixabank/Bankia, the CNMC cleared the merger in Phase I, also with commitments addressing potential local-level post-transactional concerns along the lines of points (ii) and (iv) above.

On May 31 2024, BBVA notified the CNMC of its intention to acquire Banco Sabadell[68]. BBVA, Spain’s second largest lender, had launched earlier in the year a takeover bid for Banco Sabadell, the country’s fourth largest lender and a significant source of financing for SMEs. Both BBVA and Banco Sabadell have been categorized as Significant Institutions and therefore fall under the direct supervision of the European Central Bank.

After a considerable delay, on November 12, the CNMC announced the launch of a Phase II investigation into the transaction. The delay was caused by Banco Sabadell’s belated responses to several requests for information from the authority. In its Decision, the CNMC identified competition concerns in three areas: (i) retail banking (concerns that the transaction could result in less favorable terms and conditions for consumers and SMEs, and that BBVA would likely close branches post-merger, particularly in rural areas); (ii) payment services (concerns that after acquiring Sabadell’s sizable payment services business BBVA would raise commissions, particularly on SMEs); and (iii) cash machines (concerns that Sabadell’s customers would see the number of cash machines they can access reduced, due to a curtailment of existing agreements with other banks after the transaction).

In order to alleviate the CNMC’s concerns, BBVA offered several commitments. Regarding retail banking, BBVA committed to maintain Sabadell’s contractual terms in geographic areas where the transaction would result in a duopoly or a monopoly. In addition, BBVA proposed further commitments aimed at supporting SMEs and consumers deemed financially vulnerable. Moreover, BBVA committed not to close any branches in rural or impoverished areas, and not to close any offices servicing SMEs. With respect to payment services and cash machines, BBVA offered to divest any excess participation in companies managing payment systems and guaranteed that all of Sabadell’s existing agreements with other banks will remain in force for 18 months, thereby ensuring continued access to cash machines for existing Sabadell’s customers. However, the CNMC considered these commitments insufficient[69], alleging that the commitments did not fully address the concerns raised by the transaction. As a result, the CNMC decided to open a Phase II investigation. In May 2025, the CNMC finally issued a conditional clearance decision, accepting a package of commitments that went beyond those initially proposed by BBVA (CNMC, 2025c). These include obligations to keep bank branches open in remote areas, maintain existing credit lines for SMEs, and preserve current contractual terms related to payment systems and ATMs. The duration of these commitments varies, with specific measures required to remain in force for either 18 months or three years, depending on their nature.

The Spanish Government, which holds ultimate authority to clear the transaction under the Spanish Competition Act[70], took an unprecedented step by launching a public consultation to gather feedback on the transaction’s potential impact on public interest objectives (La Moncloa, 2025b)[71]. Following this consultation, the government approved the deal but imposed strict and arguably draconian conditions on BBVA (Ministerio de Economía, Comercio y Empresa, 2025), hampering the viability of the transaction. This move drew criticism from the Commission, which has since initiated infringement proceedings against Spain (Aguado, 2025).

3. The CNMC triggered commission review of Qualcomm/Autotalks under article 22 EUMR[Up]

The CNMC, alongside the Belgian, French, Italian, Dutch, Polish, and Swedish competition authorities initially requested the Commission to review Qualcomm’s acquisition of Autotalks under Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation (“EUMR”) (CNMC, 2023). Another eight competition authorities joined the request and the Commission accepted the referral on August 17 2023[72]. The transaction concerned Qualcomm, a US multinational operating in the development and sale of semiconductors and software and Autotalks, a company specializing in automotive semiconductors.

In response to increasing opposition from competition authorities, including the Commission, Qualcomm decided to abandon the transaction. This marked the second instance in which the Commission accepted a below-threshold referral after the Illumina/Grail referral[73], a mechanism that has since come under scrutiny following the Court of Justice’s judgment on the matter[74]. It remains to be seen whether the Commission will continue to utilize this approach, especially in light of NVIDIA’s recent legal challenge (Yun Chee, 2025), after the Italian competition authority referred its below-threshold acquisition of Israeli start-up Run:AI—a transaction that was ultimately cleared unconditionally by the Commission[75].

4. Infringement proceedings in mergers[Up]

The CNMC was also very active in the enforcement of merger control, sending a clear signal that the disregard of those rules will face great penalties. The CNMC not only investigated and sanctioned typical merger control infringements, such as failures to notify transactions that meet the national thresholds (see point 4.1 below) or non-compliance with accepted commitments (see point 4.2 below), but went one step further and also targeted companies that provided misleading information in the context of merger proceedings (see point 4.3 below). This increased enforcement reveals a clear commitment from the CNMC to protect the merger control system in Spain.

4.1. Gun-jumping proceedings[Up]

The differences between EU and Spanish merger control are evident in the number of gun-jumping proceedings. As expected, the CNMC consistently received fewer merger notifications than the Commission (European Commission, 2025b)[76]. Yet, between 2020 and 2024, the CNMC opened significantly more infringement proceedings for gun-jumping (see Table 1 below). To date, the Commission has imposed fines on seven occasions for failure to notify or for implementing a merger infringing the standstill obligation[77].

Table 1.

List of Gun-Jumping Proceedings Initiated by the CNMC (2020-2024)

| Year | Parties | Fine |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | KKR GeneraLife [78] | EUR 1.1 million |

| 2024 | Generalife Clinics/Ginemed [79] | EUR 510,000 |

| 2024 | Marcial Chacón e Hijos/Electra la Honorina SL – Decail Energía [80] | EUR 13,320 |

| 2022 | Albia / Tanatorio la Paz [81] | EUR 250,000 |

| 2022 | Albia/Tanatorio De Marin [82] | EUR 25,000 |

| 2022 | Funespaña/San Vicente [83] | EUR 110,000 |

| 2022 | Xfera [84] | EUR 1.5 million |

| 2022 | Electra Alto Miño/Activos Arnoia [85] | EUR 30,000 |

| 2022 | Luxida Santa Clara [86] | EUR 12,000 |

| 2021 | Albia/Tanatorios Mostoles [87] | EUR 300,000 |

| 2021 | Funespaña/Alianza Canaria [88] | EUR 100,000 |

| 2021 | Dgtf/Parpública/Tap [89] | EUR 50,000 |

Source: CNMC.

4.2. Infringement proceedings for failure to comply with commitments[Up]

Between 2020 and 2024, the CNMC fined 7 undertakings for failing to comply with the commitments offered in their merger proceedings, as seen on Table 2 below. To date, the Commission has not fined any company for failing to comply with the commitments offered during the merger proceedings[90].

Table 2.

List of Infringement Proceedings for Failure to Comply with Commitments Initiated by the CNMC (2020-2024)

| Year | Parties | Fine |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | Naviera Armas/Trasmediterránea [91] | EUR 450,000 |

| 2023 | Mooring Port Services/Cemesa Amarres Barcelona [92] | EUR 80,000 |

| 2023 | Telefónica/Acuerdo DAZN [93] | EUR 5 million |

| 2023 | Telefónica/Fusión Terminales Móviles [94] | EUR 6 million |

| 2022 | Telefónica Compromiso 4 [95] | EUR 5 million |

| 2021 | Disa [96] | EUR 1 million |

| 2021 | Repsol / Petrocat [97] | EUR 850,000 |

Source: CNMC.

4.3. The CNMC fined Rheinmetall for providing misleading information in a merger proceeding[Up]

The CNMC’s Decision against Rheinmetall marked the first time the authority has fined a company for providing misleading information in merger proceedings (Crespo and Sánchez, 2024). The EUR 13 million fine (EUR 6.5 million for each infringement) establishes crucial precedent regarding disclosure obligations in Spanish merger notifications[98] (see also CNMC, 2024d).

This case reveals a significant gap in Spanish competition law compared to EU law. While Article 62(3)(c) of the Spanish Competition Act establishes that providing misleading information in response to information requests constitutes a serious infringement, it does not address misleading information in the filing form itself. This contrasts with Article 14(1)(a) of the EUMR, which explicitly covers incorrect or misleading information in merger notification forms. The Decision raises important questions about the principle of legality concerning the first infringement. This precedent-setting issue may lead the Spanish National Court to conclude that the first fine lacks legal basis and annul that portion of the Decision. The Spanish National Court has temporarily suspended fine payment pending final judgment[99].

This case highlights another shortcoming in Spanish law: unlike the EUMR, the Spanish Competition Act does not expressly allow the CNMC to dissolve mergers approved based on incorrect information[100]. This gap may prompt future legislative reforms.

The delayed emergence of such enforcement reflects the absence of explicit provisions in Spanish law, contrasting with EU practice where similar conduct has been addressed since the 1989 Merger Regulation[101], with the first sanctioning proceedings dating back to 1999[102].

VI. STATE AID [Up]

Although State aid is European in nature, landmark cases that originated in a purely Spanish context have contributed significantly to the shaping of EU competition law. Notably, a series of Spanish cases gave rise to decade-long litigation sagas (Spanish Goodwill and Lico Leasing, points 2 and 3 below) that made fundamental contributions to the interpretation of the notion of selectivity in State aid (see point 1 below), and developed the Commission’s duty to reason the selectivity of a State aid measure during the preliminary investigation (EDP España and Naturgy) (see point 4 below).

1. The Court of Justice defined the concept of “selectivity” in the Spanish Goodwill saga[Up]

In October 2021, the Court of Justice handed down the last judgment of the so-called “Spanish Goodwill saga”, clarifying the concept of “selectivity” in State aid. The ruling put an end to the main part of a decade-long litigation, including eight cases on appeal[103].

In late 2001, Spain introduced a provision in its corporate tax law[104] providing that in the event an undertaking taxable in Spain acquires a shareholding greater than 5% in a “foreign company” and retains it for at least one year, the resulting goodwill may be deducted via amortization from the taxable base. However, that deduction did not apply to acquisitions of shares in Spanish companies. The Commission found that this difference amounted to illegal and incompatible State aid because it conferred an unjustified advantage to Spanish companies in the context of competitive takeover bids. The Commission thus ordered the recovery of the aid in its Decisions of 2009 and 2011[105].

In 2014, the General Court annulled the Commission Decisions, finding that the Commission had failed to establish the selective nature of the tax measure[106]. In particular, the General Court highlighted the general nature of the measure, which did not target a particular “category of undertakings” and was potentially available to all[107]. In 2016, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice quashed the General Court’s ruling, relying on a broader interpretation of the concept of selectivity[108], and referred the case back to the General Court, which, in November 2018, upheld Decisions[109]. On appeal, in October 2021, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice confirmed the latter, putting an end to the protracted dispute, and thus “crystallised” the broad interpretation of selectivity set out in its previous ruling[110].

Through these rulings, the Court of Justice clarified that in order to determine whether an aid measure is selective, it is irrelevant that the measure grants an advantage to a limited group of undertakings with specific features[111]. In sum, “[a]ll that matters […] is [whether] the measure [has] the effect of placing the recipient undertakings in a position that is more favourable than that of other undertakings […] in a comparable factual and legal situation”[112]. Therefore, a “general” derogation from the reference framework may still be selective if it favors some undertakings vis-à-vis others. In other words, selectivity is not an “absolute” concept based on the general or limited scope of an aid measure but a “relative” one based on the differential effect created.

In addition, the Court of Justice established that the definition of an aid measure by reference to specific “behavioral” characteristics, such as acquisitions of shareholdings, may also make it selective (see further Kyriazis, 2021).

2. The General Court upheld the principle of legitimate expectations, giving another twist to the Spanish Goodwill saga[Up]

In 2014, the Commission adopted another Decision where it assessed a new interpretation of the tax scheme by the Spanish authorities in the form of a binding opinion, and concluded that this interpretation extended the possibility of deducting financial goodwill to indirect acquisitions of shareholdings in non-resident companies, which amounted to new aid, and thus declared it illegal and incompatible[113].

Spain and multiple companies challenged the Commission’s 2014 Decision. The General Court stayed these cases pending the outcome of the first litigation proceedings mentioned above, which concluded in 2021.

On September 27 2023, the General Court annulled the 2014 Decision, finding in essence that the indirect acquisitions of shareholdings were already covered by the 2009 and 2011 Decisions[114], and therefore, in adopting the 2014 Decision, the Commission had withdrawn two valid Decisions that conferred a legitimate expectation on Spain to implement the tax scheme (even if declared incompatible), and on private operators not to have to repay part of the illegal aid[115]. Accordingly, the General Court annulled the 2014 Decision in its entirety[116].

3. The Court of Justice concluded a decade-long litigation over the “Spanish Tax Lease System” (Lico Leasing)[Up]

In 2011, following complaints, the Commission opened a formal investigation against a Spanish Tax Lease System (“STLS”), which essentially enabled shipping companies to purchase ships built by Spanish shipyards at a 20-30% rebate[117]. In 2013, the Commission concluded that three out of the five tax measures conforming the STLS amounted to State aid under Article 107(1) TFEU and declared them illegal and partially incompatible, thus ordering Spain to recover the advantages[118]. The Commission found that the SLTS granted an advantage to economic interest groupings (“EIGs”) and their investors, which then partly transferred the advantage to shipping companies that purchased a new ship.

Spain, Lico Leasing SA and Pequeños y Medianos Astilleros Sociedad de Reconversión (“PYMAR”) lodged actions for annulment against the 2013 Decision. In the first ruling of the Lico Leasing saga in 2015, the General Court upheld the applicants’ arguments that the Commission had erred in concluding that the aid was selective[119].

The Commission appealed to the Court of Justice, which set aside the General Court’s ruling in 2018, finding, in particular, that the General Court had erred in applying the concept of selectivity, and referred the cases back to the General Court to rule on the matter and the remaining pleas[120].

In 2020, the General Court dismissed the actions for annulment lodged by Spain, Lico Leasing and PYMAR[121]. Specifically, the General Court found that (i) the STLS was selective insofar it granted broad discretionary powers to the Spanish tax authorities when applying the tax scheme[122], and (ii) the Commission did not err in ordering the recovery of the tax advantages from the EIGs and their investors alone, even if the tax advantages had been partly transferred to the shipping companies[123]. In addition, the General Court dismissed the applicants’ arguments that the Commission had failed to state reasons, infringed the principles of equal treatment, legitimate expectations, and legal certainty in ordering the recovery of the aid.

Spain, Lico Leasing, PYMAR, and 29 other entities that had intervened in the first appeal before the Court of Justice, appealed again to the Court of Justice against the judgment rendered by the General Court once the case was referred back to it. On February 2 2023, the Court of Justice dismissed all grounds of appeal except one (failure to state reasons on the identification of the beneficiaries of the STLS for recovery), and gave final ruling on the cases, annulling the Decision in part[124]. Regarding the assessment of selectivity, the Court of Justice recalled that discretionary aid measures confer a selective advantage[125]. Accordingly, the three-step methodology (i. e., reference framework/difference of treatment/justification) to assess whether a tax measure of general nature confers a selective advantage is not applicable to the STLS[126]. The relevant national law—as interpreted by the Court and not having been contested in time by the applicants[127]—afforded significant discretion to the tax authorities when applying the STSL and, therefore, granted a selective advantage[128]. The Court also rejected that the General Court had to examine whether the exercise of discretion by the Spanish tax authorities actually granted a selective advantage[129]. Regarding the definition of the beneficiaries in the recovery order, the Court of Justice found that the General Court had provided insufficient reasons to reject the appellants’ challenge that the STLS transferred the advantage from the EIGs and their investors to the shipping companies[130]. In particular, the General Court merely indicated that the 2013 Decision had identified the EIGs and their investors as the beneficiaries of the aid and that this finding was not disputed; the Court of Justice, however, found that such a challenge was necessarily implicit in the applicants’ arguments[131]. Accordingly, the Court of Justice set aside the judgment of the General Court and gave final ruling on this point, finding that it was apparent from the 2013 Decision, and the rationale of the STLS, that the latter intended to transfer part of the advantage also to the shipping companies and not just the EIGs and their investors[132].

4. The Court of Justice defined the Commission’s obligation to reason the selectivity of an aid measure during the preliminary investigation phase (EDP España and Naturgy v Commission)[Up]

In 2007, Spain established a “remuneration for capacity” scheme aimed to promote investment in the production of electricity, which included an “environmental incentive” for coal-fired power stations to install new sulfur oxide filters to reduce emissions. In 2015, the Commission launched an investigation into the capacity mechanism market in multiple Member States. In 2017, the Commission initiated a formal investigation into the Spanish environmental incentive scheme[133].

In 2018, Naturgy Energy Group (“Naturgy”), an undertaking involved in the generation of electricity through coal-fired power stations, among others, which benefited from the Spanish incentive scheme, challenged the Commission’s decision to open a formal investigation[134]. EDP España, another beneficiary of the Spanish incentive scheme, intervened in support of Naturgy. Naturgy argued, inter alia, that the Commission had infringed its duty to state reasons concerning the selectivity of the Spanish environmental incentive scheme. The General Court dismissed Naturgy’s action recalling that the decision to open the formal procedure may be limited to summarizing the relevant issues, including a preliminary assessment of the qualification of the measure as State aid, and explaining the doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market[135]. In particular, the General Court concluded that the Commission had sufficiently reasoned why the Spanish incentive scheme favored certain coal-fired power plants over others or over power plants generating electricity from other technologies[136]. The General Court noted that “if the arguments of the applicant and the interveners were to be accepted, […] this would result in the blurring of the boundary between the decision to open the formal examination procedure and the decision to close that procedure”[137].

Both Naturgy and EDP España appealed the judgment of the General Court[138]. The appellants argued that the standard to state reasons is the same for the Commission regardless of whether the decision adopted opens or closes the formal investigation procedure, relying on Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia and Retegal v Commission [139], and that the General Court had erred in discarding this precedent as irrelevant. The appellants argued further that the Commission has the obligation to assess the selectivity of the measure by analyzing the comparability of the beneficiaries with other entities pursuant to Commission v Hansestadt Lübeck [140]. The Court of Justice found that, even if, in a decision opening a formal investigation procedure, the Commission undertakes a preliminary assessment of the relevant measure, the Commission has to determine whether the aid measure constitutes State aid[141]. As the qualification of the measure as State aid deploys legal effects, including the suspension of the measure and the duty for national courts to draw the appropriate conclusions in case of infringement of the said standstill obligation, the Commission is required to disclose its reasoning “in a clear and unequivocal fashion”[142]. The Court of Justice also found that, contrary to the General Court’s findings, (i) the precedent Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia and Retegal v Commission was relevant, even if it concerned the duty to state reasons for the Commission in a decision closing a formal investigation procedure; and (ii) the Commission was obliged to undertake the comparability analysis pursuant to Commission v Hansestadt Lübeck [143]. However, none of the above was clear from the General Court judgment and the Commission 2017 decision[144]. Accordingly, the Court of Justice set aside the judgment of the General Court and annulled the Commission 2017 decision to open the formal investigation procedure[145].

VII. THE ROAD AHEAD[Up]

Between 2020 and 2024, Spanish competition law has undergone significant transformation, marked by an increasingly dynamic interplay with the European Union’s legal framework. The transposition of the ECN+ Directive and Directive 2020/1828 on collective redress exemplifies the deepening integration between national and EU-level competition enforcement. Spain’s foreign direct investment (FDI) screening regime has similarly evolved in tandem with broader EU developments. Initially introduced as temporary pandemic-era measures, these controls have since become a permanent fixture, now aligned with the EU’s FDI Regulation. Today, nearly all Member States—including Spain—have adopted national screening mechanisms aimed at protecting strategic sectors while preserving the EU’s fundamental openness to foreign investment. Enforcement efforts are likewise becoming more coordinated, particularly in response to anti-competitive practices within the digital economy.

At the same time, the Spanish regime retains distinct characteristics that both enrich and diverge from the broader EU framework. One such distinction is the national market share threshold, which allows the CNMC—and, when appropriate, the European Commission via EUMR referrals—to scrutinize acquisitions of companies with significant market influence despite falling below EU turnover thresholds. The CNMC has also taken a notably proactive stance in enforcing merger control rules, especially in relation to gun jumping, in contrast to the Commission’s relatively limited action in this area. Additionally, the CNMC has intensified its crackdown on bid-rigging practices, leveraging advanced tools such as the BRAVA algorithm to detect collusion in public procurement. These efforts not only underscore Spain’s enforcement priorities but also contribute to the integrity of procurement systems across the EU.

Nonetheless, there remains room to improve legal coherence between national and EU competition regimes. The boundaries between national and European legal frameworks are not always well-defined, as evidenced by recent cases such as Booking.com and Cabify/Auro [146]. In the former, national-level enforcement raised concerns about potential misalignment with the objectives of the DMA. In the latter, a preliminary reference from the Madrid Court of Appeal underscored the ongoing legal uncertainty in delineating the boundaries of Spanish and EU law.

The trends observed over the past five years suggest that further legislative refinement may be both necessary and imminent—particularly to address identified gaps in the Spanish Competition Act when viewed in light of the EU framework, as evidenced by the Rheinmetall case[147]. Moreover, enforcement actions are expected to increasingly target the digital sector. The Commission’s recent fines on Apple and Meta under the DMA signal a heightened scrutiny that will likely continue at both EU and national levels. Against this backdrop, enhanced coordination between the CNMC and the Commission will be critical to ensuring consistency and effectiveness in enforcement.

The Spanish Government’s recent public consultation on the proposed BBVA/Banco Sabadell merger introduces new questions concerning the intersection of political oversight and technical regulatory assessment. The manner in which the Government exercises its discretionary authority in this high-profile case may have significant implications for the perceived objectivity and independence of the merger control process. This episode will serve as a valuable indicator of institutional robustness and the integrity of competition enforcement mechanisms.

Finally, forward-looking statements by CNMC President Cani Fernández before the Spanish Congress highlight the institution’s expanding regulatory role beyond core competition enforcement (Fernández, 2025). The CNMC is set to act as Spain’s Digital Services Coordinator under the Digital Services Act (“DSA”)[148], and will take on new responsibilities under the European Media Freedom Act (“EMFA”)[149], including assessing the impact of media mergers on pluralism and editorial independence.[150] In its capacity as energy market regulator (pending the establishment of a separate national regulator), the CNMC will also intensify its efforts to address systemic vulnerabilities in the electricity sector, with particular emphasis on integrating renewable energy sources, promoting sustainability, and protecting consumers—especially in the wake of the nationwide blackout of April 2025.

In sum, the period from 2020 to 2024 has been one of notable evolution and growing sophistication for Spanish competition law. The developments observed reflect a dual movement: closer alignment with EU priorities and the assertion of distinctive national approaches. While integration and harmonization have advanced considerably, areas of tension and ambiguity remain, particularly as new regulatory instruments such as the DMA, DSA, and EMFA take root. The CNMC’s expanding mandate signals a broader transformation of competition authorities into multi-sectoral regulators equipped to address emerging challenges in the digital, media, and energy landscapes. As Spain continues to adapt its legal and institutional frameworks, the coming years will be critical for consolidating these gains and ensuring that competition policy remains a robust, forward-looking tool for economic governance.