eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2024.46.03

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

A model of implementation for the family check-up

in community mental health settings

Un modelo de implementación del family check-up en entornos comunitarios

de salud mental

Um modelo de implementação para o check-up familiar em ambientes de saúde mental comunitários

Elizabeth A. STORMSHAK*  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515

Anne Marie MAURICIO*  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0818-3249

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0818-3249

Anna Cecilia MCWHIRTER**  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0344-0493

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0344-0493

Lisa REITER**

*University of Oregon & **Northwest Prevention Science

Received date: 18.VII.2024

Reviewed date: 10.X.2024

Accepted date: 11.XI.2024

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Elizabeth Stormshak: E-mail: bstorm@uoregon.edu

Introduction

Evidence-based models for prevention of mental health and substance misuse among youth are the gold standard for implementation in community settings. Yet, the majority of model programs have been poorly implemented across communities, or not implemented at all. Reasons for this include lack of funding for implementation structures, lack of fidelity in community settings, and limited resources for implementation across health care settings where children and families access care (Peters-Corbett et al., 2024). In this paper, we discuss the Family Check-Up (FCU) and review research that supports its translation to community implementation. We also describe our implementation model in community settings in the U.S. and internationally, and we discuss future plans for measurement of implementation and clinical outcomes in community practice.

The Family Check-Up Model for Prevention of Mental Health and Behavioral Problems

The FCU was developed in 1995 as a solution to several increasing challenges in the implementation of evidence-based parenting skills training programs, including family participation and delivery of programs in community settings with fidelity. Barriers such as transportation, childcare, time, and privacy all prevented parents from participating in parenting groups, which were the standard of care at that time. Additionally, parenting group uptake was reduced in community settings, such as schools, where providers could not accommodate parent work schedules. The FCU was developed as a brief, targeted model that focused on parents’ strengths, with the potential to reach more parents by reducing intervention delivery time by tailoring the model to individual families and children.

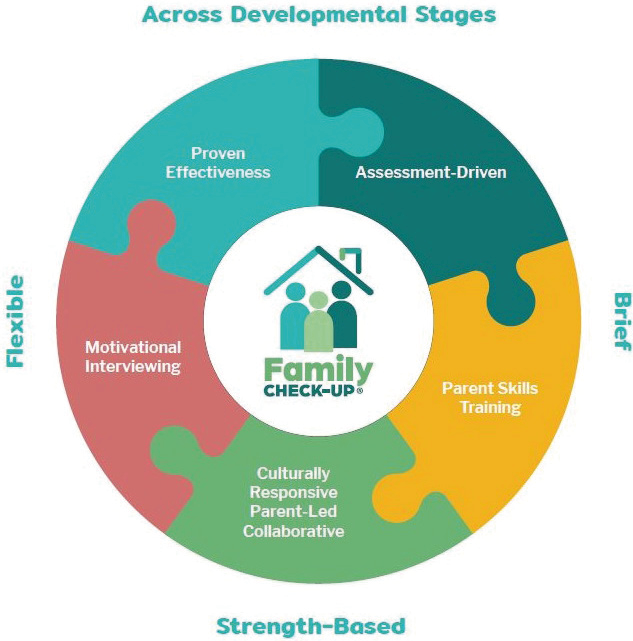

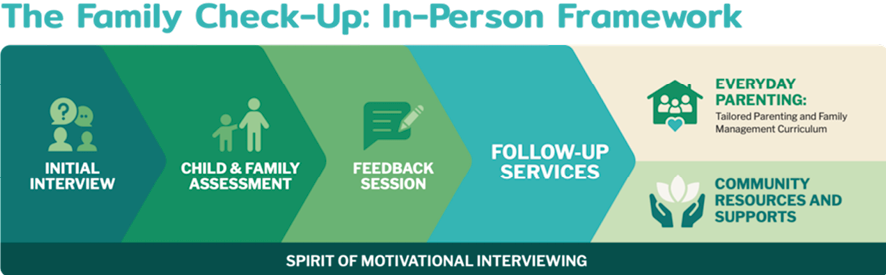

The FCU, originally developed to reduce substance use, problem behaviors at school, and academic problems in middle– and high-school populations (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007), was first evaluated in 1995 in a randomized controlled trial that was delivered in middle school (Dishion et al., 2003). Since that time, 100’s of studies have demonstrated the FCU’s effects across the lifespan, with significant effects on multiple mental health and behavioral outcomes (e.g., Hails et al., 2024; Lundgren et al., 2023; Piehler et al., 2024). Guided by Miller and Rollnick’s (2002) original Motivational Interviewing model, the FCU was developed as a strength-based approach designed to motivate parents to consistently use effective parenting strategies. The FCU is a second-generation intervention, rooted in the Parent Management Training–Oregon Model developed at Oregon Social Learning Center (Dishion et al., 2016), and conceptually linked to many other behavioral parent training programs, including The Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2018), Triple P (Sanders, 1999), and Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2016), with a foundation in behavioral parent training that forms the core curricula. However, unlike these programs, the FCU was intentionally developed as a “check-up” enabling uptake in a range of health care systems that support child mental health, with the goal of delivering brief interventions to reduce risk and support change. The FCU was also developed as an assessment-driven pre-intervention tool that precedes parenting training, with the goal of motivating caregivers to engage in parenting support that is specifically focused on their strengths and self-identified areas of concern. The FCU in-person program begins with three steps: an initial interview, an assessment, and a feedback session. The initial interview focuses on eliciting information about the family context and family strengths and concerns, using motivational interviewing strategies. The assessment includes questionnaires and videotaped family interaction tasks to gather additional information about the family. The feedback session combines information gathered from the initial interview and assessment, which is then used to discuss parent goals. The feedback session is designed to foster motivation, help parents understand their strengths and areas of growth, and connect families to appropriate resources to meet their individualized needs, which might include parenting skills training and support (Connell et al., 2023; Stormshak & Dishion, 2009). Typically, after the feedback session, the Everyday Parenting curriculum (EDP; Stormshak et al., 2024) is used to foster parenting skills. The choice of parenting skills is tailored to the family and their goals. Some key components that define the FCU model are included in Figure 1, such as the use of motivational interviewing, assessment-driven feedback, cultural responsivity, and parent skills training that is grounded in research.

Figure 1. Key components of the Family Check-Up Model. Source: Own elaboration.

Theory of Change and Developmental Model

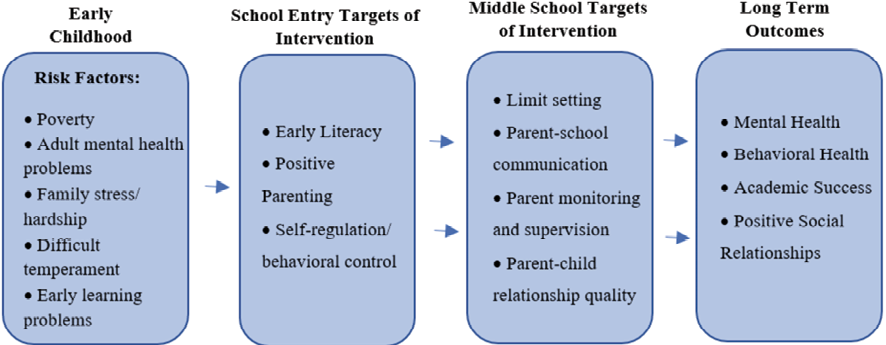

Guided by a developmental model of adaptation and risk behavior, the FCU is grounded in literature that focuses on parenting practices and family relationships as the core protective factors for preventing mental health distress and the later development of problem behavior through adolescence (e.g., Fosco et al., 2012). Decades of developmental research confirm that family relationships and parenting skills are key intervention targets that reduce mental health distress and problem behavior in youth and, if delivered as prevention during early childhood, school-age, or adolescence, these interventions are effective at sustaining long-term improvements in mental health into the adult years (Connell et al., 2023; Figure 2). Contextual stress and early risk factors, such as poverty, stressful life events, adult mental health problems, and early learning and behavior problems, directly limit parents’ ability to use effective parenting strategies at home. Parenting skills, including positive and proactive parenting, predict self-regulation and behavioral control as children enter school. Self-regulation skills, in turn, predict school adjustment, including school engagement, reductions in problem behavior, positive social relationships, and academic achievement. These targets lead to improved behavioral routines, and ultimately to positive high school outcomes, such as graduation and successful transition to work or college (Fosco et al., 2016; Garbacz et al., 2018). Parenting skills and family relationships, therefore, offer a potential solution in terms of defining a target for intervention and prevention across development, as has been done with the FCU model (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007; Stormshak et al., 2019). This developmental model of adaptation and risk behavior indicates improving parenting skills and family relationships can reduce the negative impact of contextual stress on children by enhancing child self-regulation skills and behavioral health, thereby increasing adaptation across the lifespan.

Figure 2. Developmental model predicting mental and behavioral health outcomes from early childhood to adolescence. Source: Own elaboration.

Implementation Quality Standards

When evidence-based programs are translated to community practice, their effect sizes are significantly attenuated due to declines in implementation quality. This is the result of several factors, including limited resources that diminish capacity for training and fidelity support, variability in provider skills, backgrounds, and motivation to implement, and organizational factors such as climate and leadership (Peters et al., 2024). In the last decade, several implementation models and frameworks have been proposed, and their application in any implementation effort is now recognized as a standard for high-quality implementation (Nilsen et al., 2019). Implementation models and frameworks vary in their purpose and include guiding the process of translating research into practice, understanding determinants that impact program implementation and effects, or supporting systematic evaluation of program implementation and outcomes. Implementation scientists have also begun to identify taxonomies of evidence-based strategies (e.g., assess implementation readiness) to promote positive implementation outcomes such as fidelity, reach, and sustainability, as well clinical outcomes, given particular contextual barriers and facilitators (Powell et al., 2015). As we discuss later, our approach to supporting implementation quality of the FCU in community settings is grounded in the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) process framework (Aarons et al., 2011), which has strong evidence of supporting quality implementation in community settings, including those with high proportions of vulnerable populations (Moullin et al., 2019). We have also applied the EPIS framework to guide our assessment of barriers and facilitators and corresponding selection of strategies to promote successful FCU implementation and outcomes.

Method

Overview of the Clinical Model

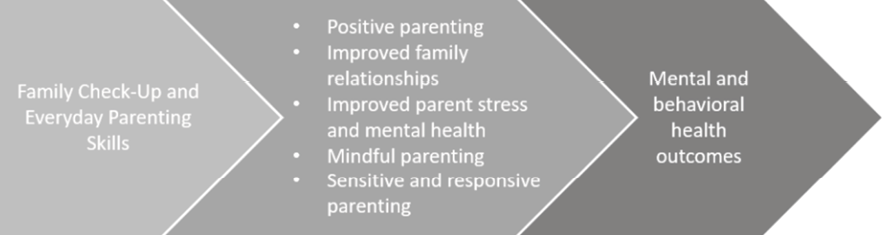

As discussed above, the FCU is a behavioral parenting intervention that helps parents develop the skills they need to support positive child behavior, as well as reduce behavior problems such as escalation of negative emotions, disruptive behavior, or emotional lability (Figure 3). As research on parenting interventions has grown, we have integrated multiple theoretical approaches consistent with the issues children and families are facing along with new, emerging research. Our work is grounded in trauma-informed care and focused on improving and sustaining healthy, trusting, family relationships to support children at home and in school. We consider parents’ history and context as we link parent well-being, self-regulation, and mindfulness skills to the use of different mindful parenting techniques and enhancing their relationship with their children. We also integrate concepts from the field of social-emotional learning, which provide parents with tools they need to identify their children’s emotions, provide emotional coaching, and support emotional growth at home. The FCU is a culturally responsive intervention, supporting collaboration, respect for autonomy, non-judgmental acceptance, and a bi-directional relationship with caregivers that is open and trusting. Parents are viewed as “experts” in their child’s behavior and family relationships, as well as collaborators in learning new skills and ways of interacting with their children in the context of their family values. We have consistently adapted the program for diverse cultural groups and contexts, and support continued cultural adaptation to enhance the intervention’s fit for all families (e.g., Lundgren et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2022).

Figure 3: The FCU and Everyday Parenting intervention targets. Source: Own elaboration.

Intervention Steps

The FCU model consists of three sessions (initial interview, child and family assessment, and feedback session) and follow-up services (e.g., Everyday Parenting (EDP) curriculum) that are tailored to the family’s needs in an adaptive model that follows from the feedback (Figure 4). Sessions occur in the office, family home, other venue, or virtually. Consistent with the tailored nature of the model, parents spend a range of time in the treatment process, from 3 hours (completing only the 3-step FCU process) to 12 hours or more (completing multiple sessions of the EDP curriculum after completing the FCU). The model is designed to be flexibly delivered based on parent’s strengths, goals, and areas of growth. Some parents may request only 1 or 2 EDP sessions following the FCU, whereas others may benefit from completing the entire program. This flexible approach is important for several reasons. First, it allows clinicians to tailor the model to fit the needs of families, including availability and readiness for change. Second, it allows clinicians and parents to prioritize key problem areas, and to focus on those areas first. Third, it allows for tailoring the parenting content based on cultural considerations and values of the family, allowing parents to reflect on how cultural identities and experiences impact their perspective and application of parenting skills. Last, our implementation model allows for variations in delivery based on the system of care. In some settings, a brief approach to intervention may be preferred, whereas in other settings longer term care can be provided.

Figure 4. The FCU process. Source: Own elaboration.

Initial Interview

The primary purpose of the Initial Interview is to establish a shared perspective between provider and family about the child’s behavior and family context and to develop mutual trust and respect. The provider gathers enough information to form a general understanding of the parents’ concerns, goals, strengths, and the parenting strategies they are already using. This session is typically 60 minutes.

Child and Family Assessment

The Assessment takes approximately 60 minutes, during which the caregiver completes questionnaires focused on domains such as parent wellbeing, child behavior, and the parent-child relationship. All caregivers (and the target child if 11 years or older) complete a questionnaire. Family members also complete videotaped parent-child interactions tasks to elicit behaviors that demonstrate family relational dynamics and highlight parenting strengths and challenge areas. Tasks are rated by providers for the quality of the parent-child relationship, parenting skills, and other behaviors specific to the caregiver role. The tasks are shared with parents at the Feedback session to generate discussion regarding parenting strengths and goals. The Assessment may be combined with the Initial Interview (e.g., if caregivers have difficulty finding time for multiple appointments).

Feedback

Preparing for the Feedback session requires synthesizing all the data collected during the Initial Interview and Assessment to develop an understanding of the key themes of family and child strengths and challenge areas that will guide the feedback process and follow-up work with the family. At the Feedback session, the provider and family discuss assessment results, including video-based feedback from the family interaction tasks, and the parent and provider collaboratively decide on goals and follow-up services. Although services might include help with problems outside of parenting (e.g., individual therapy for a parent), follow-up services often include EDP sessions (Stormshak et al., 2024).

Follow-Up Support Services

When EDP is chosen as a follow-up service, sessions include a focus on one or more of three broad domains: positive behavior support, effective limit setting, and family relationship building (Stormshak et al., 2024). Typically, only some of the sessions are selected, depending on parents’ goals from the Feedback session. EDP sessions are completed in close collaboration with parents, tailored to the family’s needs as well as the family, economic, cultural, and community context. Consistent with delivery of any behavioral parenting intervention, providers give the parent a rationale for a particular parenting practice, explain the new skill, model how to use it, have the parent practice the skill via role plays, debrief the role play practice activity, and design home practice for the parent to use the skill with the child.

Implementation Model

Northwest Prevention Science, Inc. (NPS), the FCU purveyor, supports implementation in community sites across the United States as well as several international sites including Sweden, Canada, and the Netherlands. The FCU implementation model is based on the process-focused EPIS framework and has four phases: 1) Exploration when a site explores implementation of a new evidence-based intervention (EBI); 2) Preparation when a site selects an EBI and prepares for delivery; 3) Implementation when a site begins using the EBI; and 4) Sustainment, when the site integrates the EBI into its service delivery systems (Aarons et al., 2011). Paralleling the “collaborative set” that is key to the success of the FCU model with families (Mauricio et al., 2019), progression through each of the four phases is a collaborative process between the implementation site and the NPS implementation team (Figure 5). In collaboration with site leadership, the NPS implementation team identifies specific benchmarks for each phase (e.g., timeline for certification in implementation phase); benchmarks are tailored to a site’s context and capacity. The NPS implementation team works with site leadership to self-assess progress on and motivate achievement of benchmarks. If necessary, benchmarks are adapted during implementation in response to organizational changes (e.g., unexpectedly high provider turnover). The NPS implementation team and site leadership meet as needed across all four phases of the implementation process to identify and resolve any potential barriers to implementation, and leverage facilitators.

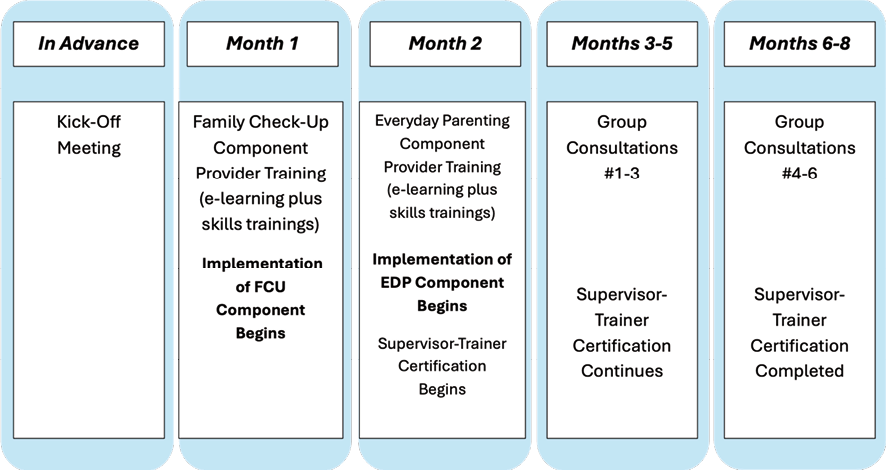

Figure 5. Implementation process and timeline. Source: Own elaboration.

The exploration phase involves information transfer about the FCU to the site’s leadership and conducting an individualized multilevel discussion of the site’s readiness and capacity to implement the FCU with fidelity and sustainability. At the organizational level, the aim of the readiness discussions are to discern that the personnel, fiscal, space, and technological resources required to implement the FCU with integrity are available. The extent to which the FCU is a fit with the organization’s mission, has buy-in from lead administrators with decision-making power, and can be integrated into the organization’s service delivery systems are also discussed as key indicators of readiness. Given high caseloads with limited supervisory support in public service sectors, a priority during the exploration phase is to discuss lead administrators’ commitment to clinical supervision time. Feasibility and acceptability of FCU implementation among providers is also discussed, and the NPS implementation team and site leadership may work collaboratively to identify providers for training and certification and to highlight potential client-related implementation barriers (e.g., high rates of premature termination of services).

Preparation Phase

In the preparation phase, an implementation team is assembled. The team includes an implementation coordinator and expert consultant from the NPS implementation team and lead administrators, supervisory staff, and providers from the implementation site; one of the team members from the implementation site, usually agency leadership, is the liaison between the NPS implementation team and the implementation site. The site acquires and allocates required fiscal, space, and technology (e.g., video equipment) resources. Implementation benchmarks and a corresponding timeline are established; benchmarks include training dates and anticipated number of providers trained in the model with specified target dates (i.e., rate of adoption). The training includes an initial self-paced e-learning program supplemented with four 3-hour virtual webinars or in-person trainings. Training involves didactic content presentation, which is effective for transferring knowledge, and enactive training methods (e.g., behavioral rehearsal, role-play, modeling) for skills acquisition. A component of the training focuses on the transfer of technological skills (e.g., process for conducting videotaped interaction tasks) required to use the FCU with fidelity.

Implementation Phase

The implementation phase involves three steps: 1) ongoing consultation, 2) tracking implementation fidelity, and 3) completing the Supervisor-Trainer certification. Trained providers who have completed the e-learning courses and webinar trainings begin using the FCU with families, and participate in monthly consultation with the NPS consultant. Consultation supports providers’ adherence to the core FCU components and competence in delivering the FCU. Consultation also supports providers’ ability to apply the model in their daily work context, problem solve barriers, and leverage facilitators. Providers are also trained to use an empirically validated, observational implementation fidelity coding system, the COACH (Smith et al., 2013). The COACH uses a 9-point scale (needs work, 1-3; acceptable work, 4-6; good work, 7-9) to assess the provider on five FCU-prescribed skills: (a) Conceptual accuracy: provider understands the FCU model; (b) Observant and responsive: provider shows clinical responsiveness to the client’s immediate concerns and contextual factors; (c) Actively structures sessions: provider skillfully structures the change process using assessment-driven case conceptualization; (d) Careful and appropriate teaching: provider is able to skillfully give feedback to increase client motivation to change; and (e) Hope and motivation: provider skillfully integrates therapeutic techniques that promote client hope, motivation, and change. The COACH’s scale is also used to rate client engagement in the session. Consistent with the FCU’s theoretical model (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007), fidelity links to change in child problem behaviors through improved parenting (Smith et al., 2013). Finally, immediately after core training in the FCU model is completed, providers selected to be on-site FCU supervisors and trainers begin the Supervisor-Trainer certification process. Supervisor-Trainer certification requires competent (i.e., COACH score of 4–6) delivery of the FCU and offering training and supervision to on-site providers that is adherent with the FCU training and supervision model. If the site encounters barriers implementing the FCU with fidelity and demonstrating capacity for sustainability, the NPS implementation team works collaboratively with site leadership to develop a remediation plan tailored to a site’s strengths (e.g., providers highly motivated to implement the FCU) and challenges (e.g., inadequate fiscal capacity).

Sustainability Phase

The sustainability phase is defined by the site’s capacity to maintain implementation of the FCU and its benefits over time. Indicators of sustainability include adoption of the FCU model and its processes into the site’s operations and service delivery systems such that resources (e.g., staff devices) and infrastructure (e.g., adequate number of trained providers) required for implementation are inherent to the site. A supervisory structure that includes the capacity to train and supervise providers independent of the NPS implementation team is also expected, as well as successful integration of the FOCU’s COACH fidelity monitoring system with feedback to the provider to support provider efficacy in the model. Another critical benchmark of the sustainability phase is identification of a funding source allocated for FCU implementation.

Results

Results from Randomized Controlled Trials

The FCU has been tested across a series of systematic and coordinated clinical trials over the past 25 years in which families and children have been randomly assigned to receive the FCU or treatment as usual, which has typically included community-based services delivered at schools or community mental health agencies. The FCU has demonstrated long-term effects on multiple child and adolescent outcomes, including reductions in depression, suicide risk, risky sexual behavior, and antisocial peer affiliation, as well as lower rates of tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol usage across adolescence and young adulthood (Connell et al., 2023; Fosco et al., 2016; Piehler et al., 2024). Research has additionally demonstrated positive intervention effects on parenting, self-regulation, academic performance, and school engagement during the transition from middle to high school (Stormshak et al., 2009), and the elementary school transition (Garbacz et al., 2024; Hails, McWhirter, Garbacz, et al., 2024; Stormshak, DeGarmo, et al., 2021). These robust findings supporting the FCU’s efficacy have led to a number of recent adaptations of the model, including a digital health version (Hails, McWhirter, Sileci, and Stormshak, 2024; Stormshak et al., 2019), and versions focused on health behavior (Berkel et al., 2021), and children with an autism diagnosis (Bennett et al., 2024).

Community Implementation

Given the FCU’s strong empirical support across diverse service delivery contexts, we began implementing the FCU in community settings starting in 2014, and we have increased implementation efforts over the last decade. The FCU is now rated as a model program on the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness review (HomVEE), and a well-supported program on the California Evidence-based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare and the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. Additionally, the FCU is rated as a promising program by the Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development and the National Institute of Justice.

International Implementations

Implementation of the FCU model in international settings began over 15 years ago, starting with a collaboration in Sweden. This collaboration began as Sweden developed national policies to train providers in evidence-based practices, including evidence-based models that were evaluated in the US and abroad. As such, we trained providers in Sweden in a large-scale roll out of the model (Mauricio et al., 2019), using the implementation approach described above. In a randomized effectiveness trial with Swedish families, those assigned to the FCU reported improvements in child oppositional behavior and had greater treatment retention than the comparison group (Ghaderi et al., 2018). Implementation efforts in Sweden continue today, and families continue to find the program acceptable and feasible in the context of the Swedish health care delivery system (Lundgren et al., 2023). Since Sweden, we have trained other international sites in the model, including sites in Canada and the Netherlands (e.g., Bennett et al., 2024). As we continue to work with international partners, we approach the implementation process with flexibility. Adaptations to the model and implementation process are evaluated, and adjustments are made to accommodate different systems of care, cultural values, and staffing needs.

Movement Towards Digital Health

Given the robust effects of the in-person FCU model, beginning in 2015, we started developing a digital health version of the FCU to enable wide-scale delivery. The FCU Online includes an assessment, computer-generated feedback, and five intervention modules that include content drawn from the FCU and EDP curriculum (Stormshak et al., 2024). The FCU Online program is one of the first internet-based interventions aimed at underserved youth and families, with intervention targets that include building positive family relationships, supporting healthy routines at home, and building school success. The FCU Online applies empirically supported eHealth strategies, such as videos, graphics, and interactive activities, supplemented with synchronized text message reminders to encourage caregiver engagement and learning (Lynch & Horton, 2016). The program includes an integrated online administration website that enables management of program features and a special portal designed for providers and administrators to view families’ program engagement. Collectively, the research on the FCU Online with families of young children and adolescents supports program acceptability and feasibility, and demonstrates its effectiveness as a parenting intervention for parents experiencing multiple contextual risk factors.

The FCU Online has been tested in three randomized clinical trials in which it was delivered with at least three sessions of supplemental telehealth coaching to support behavioral change (Stormshak et al., 2019; Stormshak, Matulis et al., 2021). In the first study, the FCU Online was offered to families with middle school students in Oregon (both rural and urban) with a high percentage of children and families at risk for poor outcomes (> 70 % economically disadvantaged, < .50 % passing state testing with proficiency). The FCU Online improved parents’ self-efficacy and child emotional problems at three months posttest, with outcomes moderated by risk in the expected direction (e.g., higher behavioral risk was associated with greater improvements; Stormshak et al., 2019). Furthermore, for children with higher levels of behavior problems, the FCU Online showed intervention effects on self-regulation. Program usage data indicated parents were highly engaged in the FCU Online and the supplemental coaching support. Most parents (73 %) completed the full FCU Online program, and parents visited each of the five FCU Online modules four or more times on average.

In the second randomized trial, we tested the FCU Online directly after the COVID-19 pandemic with middle school children and parents who reported mental health distress. Significant intervention effects were found on parent well-being (perceived stress, anxiety, and depression) and on outcomes related to parenting and family relationships, including improvements in positive and proactive parenting as well as reductions in negative parenting and family conflict (Connell & Stormshak, 2023). Mediated effects on parenting skills and parent stress predicted improvements in youth depression 4 months later (Mauricio et al., 2024). Parents reported no technology-related barriers and high consumer satisfaction. These data provide preliminary evidence for the FCU Online’s effects on target mechanisms of change in youth mental health (e.g., parenting skills, family relationships, self-regulation).

In the third study, we conducted a clinical trial of the FCU Online with parents with young children (18 months to 5 years) and histories of depression or substance misuse (Stormshak, Matulis et al., 2021). We randomly assigned parents to receive the FCU Online or a waitlist control. Eligibility criteria included endorsing depressive symptoms and/or substance misuse. Participants were predominantly low-income and receiving government assistance (i.e., 70 %); 43 % lived in a rural community; 31 % reported clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or depression at baseline; and 30 % endorsed a lifetime history of opioid misuse. At 3-months posttest the FCU Online was significantly associated with improvements in positive and proactive parenting, limit-setting skills, depressive symptoms, and parenting self-efficacy (Hails, McWhirter, Sileci, and Stormshak, 2024), with small to intermediate effect sizes. We found higher levels of parent depression and anxiety at baseline were significantly associated with telehealth coach engagement. Furthermore, low levels of initial self-reported positive parenting and limit-setting skills significantly predicted parent engagement. In general, engagement with the program and coaching components was high, with 75 % of parents participating in the intervention.

Given the promising effects of the FCU Online, we have begun implementation of the digital health model in community settings, including schools. Our FCU Online training, adapted from our in-person FCU training described above, is brief (i.e., 4 hours) and virtual to increase feasibility. Because the content of the parenting interventions is embedded in the online web-based application, the model can easily be delivered with fidelity. This facilitates uptake in settings with providers who have limited training, time, or access to continued supervision and support.

Discussion

Research on the FCU in-person and FCU Online programs, and on FCU adaptations, consistently supports that the model improves targeted parenting and family mechanisms of change to improve child and adolescent outcomes, with effects extending into young adulthood. Moreover, program engagement and satisfaction has been consistently high across studies. Considering that low participation and retention of families threatens the effectiveness and public health impact of family intervention work (Negreiros et al., 2019), the high level of engagement in and satisfaction with the FCU in conjunction with its strong effects are promising. As we enter the later stages of the science-to-practice pipeline and focus on FCU dissemination, there are many lessons learned to inform our efforts, from FCU implementation as well as from a significant body of implementation science literature.

One lesson is related to provider selection and training. For example, when we began implementing the FCU in community settings, we set a range of parameters for community agencies, including level of training, time commitments, and supervisor qualifications. Over the years, we have adjusted these parameters to accommodate a range of providers and training settings, with the goal of implementing the model throughout the continuum of care that is often part of child health care systems, including as a primary prevention model, a selected intervention, and as a targeted intervention to treat problem behavior and mental health disorders. Moreover, there is a growing shortage of providers to serve the mental health needs of children and families (National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2023), a substantially increasing trend over the past decade. The result is that states are now investing in training a bachelor’s level workforce to provide mental health services to children and families, which will increase access to care and affordability. For example, Oregon and Washington are engaged in training bachelor’s level practitioners as behavioral health specialists, which can be deployed into health care settings, schools, and substance use treatment facilities (O’Connell et al., 2024). The result of this changing workforce is that evidence-based programs must be brief and easy to use in large systems of care, which links well to our digital model in which program content is embedded, thus facilitating model delivery with fidelity.

Moreover, our implementation model has been responsive to the increasing demands on providers and diminished resources in community settings. Specifically, we adapted the original training model (4 full days of on-site training) to a partially asynchronous, self-paced training that takes approximately 8 hours, combined with remote skills trainings that last only 2 partial days. The result is that we can train more providers quickly, and support uptake of the model in a variety of settings. We have also streamlined our train-the-trainer model (i.e., Supervisor-Trainer certification) in that we work with sites to identify one or more staff members for whom completion of the Supervisor-Trainer certification process is feasible and appropriate. This provider then champions the FCU model within their agency. As NPS broadens dissemination efforts, we are working collaboratively with implementation sites to assess barriers and successes during the implementation process and using these data to inform our understanding of implementation readiness and whether model adoption will be be successful, and if success might vary by provider and site characteristics.

A big, unanswered question is whether effects found in research studies will replicate as the FCU is transferred to community settings. Towards this end, NPS is developing systems to feasibly collect data from community sites to understand 1) changes that families are experiencing as a result of their participation in the FCU and 2) variables relevant to effective implementation. For the FCU Online, assessing effectiveness and engagement in the context of real-world implementation is feasible for sites at very low burden because the program collects pre-post de-identified intervention data automatically. With an increasing number of diverse sites opting to implement the FCU Online, this will help us understand what contextual factors (e.g., site, provider, parent characteristics) are associated with intervention uptake and effectiveness.

Conclusion

This paper outlines the FCU’s trajectory from development to dissemination. We present the FCU in-person and digital programs, and discuss research demonstrating FCU’s readiness for community dissemination. We also describe the implementation model that guides us in supporting community sites to independently offer the model with fidelity to families they serve, with tailored support from the purveyor, NPS. We close with a discussion of lessons learned as we have engaged in the translation of the FCU from research to community practice, and we discuss future plans for measurement of implementation and clinical outcomes in community practice.

Contributions

|

Contributions |

Authors |

|

Conception and design of the work |

Author 1, 2, 4 |

|

Document search |

Author 3 |

|

Data collection |

Author 1, 2, 4 |

|

Data analysis and critical interpretation |

Author 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

Version review and approval |

Author 2, 3 |

Funding

The research did not have funding sources

Conflict interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest, and data presented in the paper are not false or manipulated.

Bibliographic References

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4-23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

Bennett, T., Drmic, I., Gross, J., Jambon, M., Kimber, M., Zaidman-Zait, A., Andrews, K., Frei, J., Duku, E., Georgiades, S., Gonzalez, A., Janus, M., Lipman, E., Pires, P., Prime, H., Roncadin, C., Salt, M., & Shine, R. (2024). The Family-Check-Up® Autism Implementation Research (FAIR) Study: Protocol for a study evaluating the effectiveness and implementation of a family-centered intervention within a Canadian autism service setting. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1309154

Berkel, C., Fu, E., Carroll, A. J., Wilson, C., Tovar-Huffman, A., Mauricio, A., Rudo-Stern, J., Grimm, K. J., Dishion, T. J., & Smith, J. D. (2021). Effects of the Family Check-Up 4 Health on parenting and child behavioral health: A randomized clinical trial in primary care. Prevention Science, 22(4), 464-474. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01213-y

Connell, A. M., Seidman, S., Ha, T., Stormshak, E., Westling, E., Wilson, M., & Shaw, D. (2023). Long-term effects of the Family Check-Up on suicidality in childhood and adolescence: Integrative data analysis of three randomized trials. Prevention Science, 24(8), 1558-1568. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01370-8

Connell, A. M., & Stormshak, E. A. (2023). Evaluating the efficacy of the Family Check-Up Online to improve parent mental health and family functioning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Prevention, 44(3), 341-357. doi: 10.1007/s10935-023-00727-1

Dishion, T., Forgatch, M., Chamberlain, P., & Pelham III, W. E. (2016). The Oregon model of behavior family therapy: From intervention design to promoting large-scale system change. Behavior therapy, 47(6), 812-837. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.002

Dishion, T. J., Nelson, S. E., & Kavanagh, K. (2003). The family check-up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 553–571. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80035-7

Dishion, T. J., & Stormshak, E. A. (2007). Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care (pp. x, 319). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11485-000

Fosco, G. M., Stormshak, E. A., Dishion, T. J., & Winter, C. E. (2012). Family relationships and parental monitoring during middle school as predictors of early adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 202–213. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651989

Fosco, G. M., Van Ryzin, M. J., Connell, A. M., & Stormshak, E. A. (2016). Preventing adolescent depression with the family check-up: Examining family conflict as a mechanism of change. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 82-92. doi: 10.1037/fam0000147

Garbacz, S. A., Stormshak, E. A., McIntyre, L. L., Bolt, D., & Huang, M. (2024). Family-centered prevention during elementary school to reduce growth in emotional and behavior problems. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 32(1), 47-55. doi: 10.1177/10634266221143720

Garbacz, S. A., Zerr, A. A., Dishion, T. J., Seeley, J. R., & Stormshak, E. (2018). Parent educational involvement in middle school: Longitudinal influences on student outcomes. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(5), 629-660. doi: 10.1177/0272431616687670

Ghaderi, A., Kadesjö, C., Björnsdotter, A., & Enebrink, P. (2018). Randomized effectiveness trial of the Family Check-Up versus internet-delivered parent training (iComet) for families of children with conduct problems. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 11486. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29550-z

Hails, K. A., McWhirter, A. C., Garbacz, S. A., DeGarmo, D., Caruthers, A. S., Stormshak, E. A., & McIntyre, L. L. (2024). Parenting self-efficacy in relation to the family check-up’s effect on elementary school children’s behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 38(6), 858-868. doi: 10.1037/fam0001237

Hails, K. A., McWhirter, A. C., Sileci, A., & Stormshak, E. A. (2024). Family Check-Up Online effects on parenting and parent wellbeing in families of toddler to preschool-age children.

Henggeler, S. W., & Schaeffer, C. M. (2016). Multisystemic Therapy®: Clinical overview, outcomes, and implementation research. Family Process, 55(3), 514-528. doi: 10.1111/famp.12232

Lundgren, J. S., Ryding, J., Ghaderi, A., & Bernhardsson, S. (2023). Swedish parents’ satisfaction and experience of facilitators and barriers with Family Check-up: A mixed methods study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(5), 618-631. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12913

Lynch, P. J., & Horton, S. (2016). Web style guide: Foundations of user experience design. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300225259

Mauricio, A. M., Hails, K. A., Caruthers, A., Connell, A. M., & Stormshak, E. A. (2024). Family Check-Up Online: Effects of a virtual randomized trial on parent stress, parenting, and child outcomes in early adolescence. Prevention Science. doi: 10.1007/s11121-024-01725-3

Mauricio, A. M., Rudo-Stern, J., Dishion, T. J., Letham, K., & Lopez, M. (2019). Provider readiness and adaptations of competency drivers during scale-up of the Family Check-Up. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(1), 51-68. doi: 10.1007/s10935-018-00533-0

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change, 2nd ed (pp. xx, 428). The Guilford Press. doi: 10.1097/01445442-200305000-00013

Moullin, J. C., Dickson, K. S., Stadnick, N. A., Rabin, B., & Aarons, G. A. (2019). Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science: IS, 14(1), 1-1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2023). Behavioral Health Workforce, 2023. Retrieved from https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/Behavioral-Health-Workforce-Brief-2023.pdf

Negreiros, J., Ballester, L., Valero, M., Carmo, R., & Da Gama, J. (2019). A systematic review of participation in prevention family programs. Pedagogía Social, 34, 63-75. doi: 10.7179/PSRI_2019.34.05

Nilsen, P., & Bernhardsson, S. (2019). Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC health services research, 19, 1-21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

O’Connell, W. P., Renn, B. N., Areán, P. A., Raue, P. J., & Ratzliff, A. (2024). Behavioral health workforce development in Washington state: Addition of a behavioral health support specialist. Psychiatric Services, appi.ps.20230312. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20230312

Peters-Corbett, A., Parke, S., Bear, H., & Clarke, T. (2024). Barriers and facilitators of implementation of evidence-based interventions in children and young people’s mental health care–a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 29(3), 242-265. doi: 10.1111/camh.12672

Piehler, T. F., Wang, G., He, Y., & Ha, T. (2024). Cascading effects of the Family Check-Up on mothers’ and fathers’ observed and self-reported parenting and young adult antisocial behavior: a 12-year longitudinal intervention trial. Prevention Science, 25(5), 786-797. doi: 10.1007/s11121-024-01685-8

Peters-Corbett, A., Parke, S., Bear, H., & Clarke, T. (2024). Barriers and facilitators of implementation of evidence-based interventions in children and young people’s mental health care – a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 29(3), 242-265. doi: 10.1111/camh.12672

Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., … & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation science, 10, 1-14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

Sanders, M. R. (1999). Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2(2), 71-90. doi: 10.1023/A:1021843613840

Smith, J. D., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., & Wilson, M. N. (2013). Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 962-974. doi: 10.1037/a0033950

Stormshak, E. A., Connell, A., & Dishion, T. J. (2009). An adaptive approach to family-centered intervention in schools: Linking intervention engagement to academic outcomes in middle and high school. Prevention Science, 10(3), 221-235. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0131-3

Stormshak, E. A., DeGarmo, D., Garbacz, S. A., McIntyre, L. L., & Caruthers, A. (2021). Using motivational interviewing to improve parenting skills and prevent problem behavior during the transition to kindergarten. Prevention Science, 22(6), 747-757. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01102-w

Stormshak, E. A., & Dishion, T. J. (2009). A school-based, family-centered intervention to prevent substance use: The Family Check-Up. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35(4), 227-232. doi: 10.1080/00952990903005908

Stormshak, E. A., Matulis, J. M., Nash, W., & Cheng, Y. (2021). The Family Check-Up Online: A telehealth model for delivery of parenting skills to high-risk families with opioid use histories. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.695967

Stormshak, E. A., Mauricio, A. M., & Gill, A. M. (2024). Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management practices. Research Press.

Stormshak, E. A., Seeley, J. R., Caruthers, A. S., Cardenas, L., Moore, K. J., Tyler, M. S., Fleming, C. M., Gau, J., & Danaher, B. (2019). Evaluating the efficacy of the Family Check-Up Online: A school-based, eHealth model for the prevention of problem behavior during the middle school years. Development and Psychopathology, 31(5), 1873-1886. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419000907

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2018). The Incredible Years parents, teachers, and children training series: A multifaceted treatment approach for young children with conduct problems. In J. R. Weisz & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (3rd ed., pp. 122-141). The Guilford Press.

Wu, Q., Krysik, J., & Thornton, A. (2022). Black kin caregivers: Acceptability and cultural adaptation of the Family Check-Up/Everyday Parenting program. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 39(5), 607-618. doi: 10.1007/s10560-022-00841-9

HOW TO CITE THE ARTICLE

|

Stormshak, E. A., Mauricio, A. M, Mcwhirter, A. C. & Reiter, L. (2025). A model of implementation for the family check-up in community mental health settings. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 46, 59-73. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2025.46.03 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

Elizabeth A. Stormshak. E-mail: bstorm@uoregon.edu Anne Marie Mauricio. E-mail: amariem@uoregon.edu Anna Cecilia Mcwhirter. E-mail: annacecilia@nwpreventionscience.org Lisa Reiter. E-mail: lisa@nwpreventionscience.org |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

ELIZABETH A. STORMSHAK https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515 Is a Knight Chair and Professor in the College of Education at the University of Oregon. Her research focuses on family-centered prevention of mental health and behavior problems in youth. ANNE MARIE MAURICIO https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0818-3249 Is an Associate Research Professor at the University of Oregon Prevention Science Institute. Her research focuses on the development, implementation, and evaluation of culturally competent evidence-based interventions for sustainable delivery in community practice settings. ANNA CECILIA MCWHIRTER https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0344-0493 Is a Trainer and Implementation Consultant at Northwest Prevention Science, Inc. Her work and research focus on parent behavioral training and family interventions for children and youth, and implementation practices and consultation support for providers nationally. LISA REITER Is the Chief Operating Officer and Chief Implementation Officer for Northwest Prevention Science, the purveyor organization for the Family Check-Up model. She has 30 years of experience working in the evidence-based practice field and training professionals in EBP’s. |

Note

Research was conducted in accordance with ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Report and American Psychological Association and received approval from the Human Subjects Board of the University of Oregon. Participants were informed of the study objectives and provided written informed consent, ensuring their anonymity, confidentiality, and data protection.