eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2024.46.05

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

Preliminary test of a spanish version of the group engagement measure to advance evidence based practice in groups

Prueba preliminar de una versión en español de la medida de participación grupal para avanzar en la práctica basada en evidencia en grupos

Teste preliminar de uma versão em espanhol da medida de participação em grupo para promover a prática baseada em evidências em grupos

Mark J. MACGOWAN*  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515

Maria Isabel TAPIA**  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0566-9497

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0566-9497

Catalina CAÑIZARES***  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-5205

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-5205

*Florida International University, **University of Miami & ***New York University

Received date: 08.VIII.2024

Reviewed date: 18.IX.2024

Accepted date: 14.XI.2024

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Mark Macgowan: School of Social Work, Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC5-513, Miami, 33193. Email: Macgowan@fiu.edu

|

KEYWORDS: Group counseling; group engagement; Spanish; group assessment; family groups. |

ABSTRACT: Evidence-based practice in groups includes research-based measures to assess group processes and outcomes. However, there are few evidence-based, culturally relevant instruments that can assist professionals in delivering evidence-based groups in Spanish to increase participant’s engagement and retention. This paper describes a project to translate a reliable and valid English version of the Group Engagement Measure (GEM) into Spanish and its relevancy to improve research outcomes when implementing socio-educational interventions in communities with family participation. The process of translation was deliberate and methodical, which produced a Spanish version for empirical testing named Medida de Compromiso en Trabajo Grupal (GEM-27). The measure demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .94, and a low standard error of measurement (3.74). As a part of evidence-based practice in groups, the Spanish GEM can help advance the measurement of important connections in the group, strengthening the helpfulness of group work in Spanish countries. |

|

PALABRAS CLAVE: Asesoramiento grupal; compromiso grupal; español; evaluación grupal; grupos familiares. |

RESUMEN: La práctica de grupos basada en la evidencia incluye medidas basadas en la investigación para evaluar los procesos y los resultados de los grupos. Sin embargo, existen pocos instrumentos basados en la evidencia y culturalmente relevantes que puedan ayudar a los profesionales a impartir grupos basados en la evidencia en español para aumentar el compromiso y la retención de los participantes. Este artículo describe un proyecto para traducir al español una versión fiable y válida en inglés del Group Engagement Measure (GEM) y su relevancia para mejorar los resultados de la investigación cuando se implementan intervenciones socioeducativas en comunidades con participación familiar. El proceso de traducción fue deliberado y metódico, lo que produjo una versión española para pruebas empíricas denominada Medida de Compromiso en Trabajo Grupal (GEM-27). La medida demostró una alta consistencia interna, con un alfa de Cronbach de .94, y un bajo error estándar de medida (3.74). Como parte de la práctica basada en la evidencia en grupos, el GEM español puede ayudar a avanzar en la medición de conexiones importantes en el grupo, fortaleciendo la utilidad del trabajo en grupo en los países españoles. |

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Aconselhamento de grupo; envolvimento de grupo; espanhol; avaliação de grupo; grupos familiares. |

RESUMO: A prática baseada em evidências em grupos inclui medidas baseadas em pesquisas para avaliar os processos e resultados do grupo. No entanto, existem poucos instrumentos baseados em evidências e culturalmente relevantes que possam ajudar os profissionais a realizar grupos baseados em evidências em espanhol para aumentar o envolvimento e a retenção dos participantes. Este artigo descreve um projeto de tradução para espanhol de uma versão inglesa fiável e válida da Group Engagement Measure (GEM) e a sua relevância para melhorar os resultados da investigação na implementação de intervenções socioeducativas em comunidades com participação familiar. O processo de tradução foi deliberado e metódico, o que produziu uma versão espanhola para testes empíricos denominada Medida de Compromiso en Trabajo Grupal (GEM-27). A medida demonstrou uma elevada consistência interna, com um alfa de Cronbach de 0,94, e um baixo erro padrão de medição (3,74). Como parte da prática baseada em evidências em grupos, o GEM espanhol pode ajudar a avançar na medição de ligações importantes no grupo, reforçando a utilidade do trabalho de grupo nos países espanhóis. |

Introduction

Group interventions with families are aimed at recognizing their potential and developing skills that allow them to improve their relationships and increase their well-being. The group becomes an important space for the development of the skills of the families that comprise it (Orte et al., 2023; Torío, 2017). In addition, the group helps to create bonds of relationship, trust and mutual help (Gomila et al., 2023) and contributes to generating dynamics of co-responsibility in the community (Riera Romaní, 2011). Delivering group work to families is challenging, as family dynamics are different from group dynamics. For this reason, the evidence-based group leader (or facilitator) must understand and adopt new processes related to improved outcomes and group dynamics, in addition to developing therapeutic alliances, group cohesion, and commitment among group members (Lo Coco et al., 2022; Alldredge et al., 2021; Burlingame et al., 2017). The group leader must be able to build bonds within the group and apply the best available evidence using evaluation tools to ensure that the desired processes are achieved (Macgowan, 2008; Macgowan & Astray, 2024; Macgowan & Canizares, 2023; Macgowan & Hanbidge, 2022).

The connections that members have with each other, the group worker, the group itself, and the work of the group are important and unique benefits of group work (Burlingame & Jensen, 2017; Lo Coco et al., 2022). One conceptualization of the connections within a group is engagement. Macgowan (1997) developed the Group Engagement Measure (GEM) to address the lack of a well-defined, measurable concept of engagement in group work. Previous measures of engagement were either designed for individual work or included limited items related to engagement, such as attendance. The GEM model incorporates the concepts of social integration, contracting, attendance, participation, interaction, group therapeutic alliance, and elements from three major group work models; namely, social goals, reciprocal, and remedial (Macgowan, 1997). Based on these concepts and models, Macgowan (1997) advanced that group engagement is a multidimensional construct with seven dimensions: Being present during the entire group session (Attendance), contributing verbally or by participating in group activities (Contributing), showing support for the work of the group leader (Relating to Worker), interacting with other group members (Relating with Others), agreeing with the policies and practices within the group (Contracting), making an effort to work on own problems (Working on Own Problems), and helping other group members to work on their own problems (Working on Others’ Problems). Within these seven dimensions, Macgowan (1997) created a pool of 48 items to represent each domain. Macgowan empirically tested the item pool using reliability and validity testing with a sample of adults (N = 77), mostly male (57.3 %), which included groups for parenting, substance use, and homelessness. Item analysis reduced the number of items to 37, representing the first version of the GEM (Macgowan, 1997).

Several instrument-testing studies involving other clinical and non-clinical samples tested the GEM’s reliability (internal consistency, test-retest, and interrater), validity (construct, concurrent, and predictive), and/or standard error of measurement, with favorable results (Macgowan, 1997, 2000a; Macgowan & Levenson, 2003). The first study (Macgowan, 1997) was described above. The samples in the other two studies included group work students (n = 86; Macgowan, 2000) and adult male sex offenders (n = 61; Macgowan & Levenson, 2003). To test the dimensionality of the measure, and to validate the seven dimensions, the factor structure was tested in a fourth study (Macgowan & Newman, 2005) using confirmatory factor analysis involving an aggregation of the previous three studies’ (i.e., Macgowan, 1997, 2000; Macgowan & Levenson, 2003) samples. The study confirmed the dimensionality of the original 7-factor, 37-item GEM for clinical groups (Macgowan & Newman, 2003). Two shorter versions were produced: A 7-factor, 27-item version for clinical groups, and a 5-factor, 21-item version suitable for clinical or non-clinical groups. The GEM was conceived to be used by the group leader. However, member and leader ratings were correlated in previous research (Levenson & Macgowan, 2004; Macgowan, 1997) suggesting that members could also rate their engagement with minimal rating bias.

The GEM assesses the engagement of individual members providing an overall engagement score (Macgowan, 2006a). GEM items are rated on a Likert-type scale with the following anchors: 1 = ‘Rarely or none of the time,’ 2 = ‘A little of the time,’ 3 = ‘Some of the time,’ 4 = ‘A good part of the time,’ and 5 = ‘Most or all of the time. Higher scores indicate greater engagement. The GEM was originally conceived to be completed in closed groups, where group members are the same throughout. Group leaders administer the GEM after the group members’ questions and concerns about the group have been addressed. It is considered acceptable, and not a sign of non-engagement, if group members have questions about what the group is about, the expectations of participation, and the leader’s qualifications. In closed-ended groups, this may be by the second or third session, when group members have settled into the life and purpose of the group. The measure may be administered at the end of each session to derive an engagement score, or leaders may also rate members periodically. In the latter case, leaders rate the member’s engagement over the last two sessions to indicate a typical, recent session.

The GEM has been used in several research studies and noted in one systematic review. It was used in research of an eco-developmental, parent-centered HIV preventive intervention for Hispanic parents and their middle-school children, which included a fifteen-session support group for parents (Prado et al., 2006; Tapia et al., 2006). It was used in studies on group treatment of adult sex offenders (Levenson & Macgowan, 2004; Levenson et al., 2009) and studies on group work with domestic violence offenders (Chovanec, 2012; Chovanec & Roseborough, 2017) and American Indians with depression and related trauma and grief (Brave Heart et al., 2020). Notably, a systematic review of forty measures of engagement reported that the GEM was the most useful for measuring therapeutic engagement (Tetley et al., 2011).

The GEM may be used to advance evidence-based group work (EBGW). EBGW has been defined as “a process of the judicious and skillful application in group work of the best evidence, based on research merit, impact, and applicability, using evaluation to ensure that desired results are achieved” (Macgowan, 2008, p. 3). An important part of EBGW is using reliable and valid measures to determine if desired processes and outcomes are being achieved (Macgowan, 2008). The GEM can be used to increase engagement in group work in general and with alcohol and other drug groups (AOD) in particular (Macgowan, 2003b, 2006b). Plasse (2000) used the GEM to help understand the engagement of women in a psychoeducational parenting skills group for AOD treatment. Levin (2006) used the concepts in the GEM to advance understanding of working with hard-to-reach group members.

Although the GEM has been widely used in various English-speaking groups, no version exists in other languages. Researchers from the Balearic Islands (Spain), reached out to one of the authors to develop a Spanish-language version of the GEM for a family group work project. This collaboration led to the development of a Spanish version of the GEM. This paper details the development process and the preliminary empirical testing of the Spanish version of the GEM.

Method

Measure

The English version of the GEM used for the project was the GEM-27 (Macgowan & Newman, 2005). The GEM-27 retains all seven dimensions but reduces the number of items to facilitate more timely completion. To score the GEM, all items are added and divided by the number of subscale items to obtain a subscale score. Two items are reverse-scored, which means if a group member is given a score of 2, it will be considered a 4 for scoring purposes. Likewise, if a member is given a 5, it will be considered a 1 for scoring purposes.

Translation process

The project used methods aligning with best practices in intercultural research and instrument translation (e.g., Erkut, 2010; Hulin, 1987; Sireci et al., 2006). Additionally, the authors have been involved in other projects involving cultural and language translations into Spanish (Estrada et al., 2017; Jacobs et al., 2016; Macgowan, 2000b; Waites et al., 2004). This project followed a process of steps to translate the GEM into Spanish. First, a native speaker of Spanish and fluent in English translated the measure from English to Spanish, then a native English speaker with Spanish language comprehension conducted the translation back to English. The originator of the GEM was consulted to ensure conceptual equivalence was maintained. A consensus process was used to correct any discrepancies on certain items in the measure. Finally, in keeping with variations of the Spanish language by national origin, the Spanish version had some corrections conducted by the team from Spain. Examples of corrections will be discussed in the findings section.

Statistical testing

Instrument testing included evaluating reliability through internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. Additionally, the standard error of measurement was examined, providing an index of measurement error that indicates the range within which a true score falls (Anastasi, 1988). Thus, alpha was expected to be high and the standard error of measurement low. Regarding the statistical validity tests, the sample size was insufficient for factor analysis, and there were no comparable measures available for statistical comparisons of the validity of the Spanish GEM. Finally, All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.

Intervention, groups, group leaders, and participants

The group was part of a universal prevention program involving families called Programa de Competencia Familiar – Universal (Strengthening Family Program – Universal; PCF-U 11-14), focusing on families with children between 11 and 14 years old (Orte, 2019). The development of the FCP-U 11-14 program began in 2015, and its validation was carried out between 2016 and 2019. The intervention included six two-hour weekly sessions that included a first hour of separate work with parents and children and a second hour of group work with all families. To provide the reliability data, the Spanish GEM was administered in the third session of the groups with the families.

There were four group leaders, three females and one male. Their ages ranged from 37 to 41, with a mean age of 40. Three had master’s degrees and one had an undergraduate degree. Two were psychologists and the other two specialized in education. Their experience in family work ranged from 9 years to 14 years, with an average of 12 years. They had a range of six months to a year in experience specifically related to prevention programs. These group workers were provided an orientation to the GEM and completed their ratings on fifty-one participants across the four groups.

The ethics committees of the University of the Balearic Islands and Florida International University approved the project and the use of data.

Findings and discussion

Before undergoing quantitative testing of the Spanish version of the GEM, there was a careful process of translating the measure into Spanish. The process highlighted important therapeutic concepts and their interpretation across cultures. Spanish is widely spoke across the world, but with regional differences. It is not monolithic but rich with differences depending on country. The author team include native Spanish speakers from Cuba, now residing in a predominantly Spanish speaking part of the USA (Miami), Colombia, and the Balearic Islands, Spain, where the measure would be utilized for the project. Therefore, decisions about the choice of concept and word were largely guided by the Spanish language in Spain (i.e., Castilian Spanish). Some of the concepts and words will be described, which may not reflect subtleties across Spanish-speaking locations, but by how the word or concept translated into Spanish in Spain. Two examples will illustrate the process of translating group work concepts into Spanish for the persons completing the measure, group workers.

The process of translating the GEM into Spanish

Extensive discussion took place regarding the translation of the concept of “engagement” into Spanish. Various potential terms were considered, including participación (“participation”), compromiso (“commitment”), implicación (“involvement”), and enganche (“hitch,” “linked,” or “hook”). As previously noted, the English concept of group engagement encompasses various behaviors across multiple domains. The GEM aims to capture the multidimensional richness of how individuals connect within groups, reflected in its seven dimensions. While implicación (involvement) is a possible translation, it does not fully convey the depth intended by the concept of group engagement in English. Similarly, participación (participation) was considered, but it suggests a weaker level of involvement than intended. To ensure accuracy, the authors reviewed a selection of Spanish publications to understand how engagement was defined in Spanish. Eight studies with engagement in their titles were examined – three in psychology, two in education, and one each in organizational studies, health, and sports. In half of these studies, engagement was not translated into Spanish, and the English term was used instead (Dyer et al., 2015; Magallares et al., 2017; Ramos-Diaz et al., 2016; Wood et al., 2018). Compromiso was used in three studies (Psychology, Education, Sports; Guillén & Martínez-Alvarado, 2014; Mañas-Rodríguez et al., 2016; Morcillo-Martínez et al., 2021) and implicación in one (Psychology; Ramos-Diaz et al., 2016). The authors thought that compromiso was the most appropriate translation of the concept; therefore, that name the GEM in Spanish for this project was Medida de Compromiso en Trabajo Grupal (“Measure of Commitment in Group Work”).

Another concept that required careful translation was “group worker”. The GEM was developed primarily for social work with groups, where “group worker” typically means “group leader” or “group facilitator”. However, it was unclear whether the term “trabajo grupal” would be widely used in Spain. Other options included líder del grupo, facilitador, formador, and trabajador/a (profesional). While the word formador is used for education-type groups (e.g., trainer), the word facilitador was adopted as it is widely used in Spanish speaking countries and is broader in concept so would include more than leadership in training groups.

Another consideration was how to translate the scaling of the anchors of the instrument from English into Spanish. The English version uses a Likert-type scale with the following options: “rarely or none of the time,” “a little of the time,” “some of the time,” “a good part of the time,” and “most or all of the time”. The first step was to consider a direct, literal translation. This method proved effective for certain phrases but not universally applicable. For example, the expressions “a little of the time” and “some of the time” could be translated literally as “un poco de tiempo” and “algo de tiempo,” respectively. However, these literal translations did not resonate as natural Spanish. Consequently, alternative expressions that conveyed the same meaning in English, while sounding more idiomatic in Spanish, were considered. Thus, “pocas veces” and “algunas veces” were selected. Therefore, the consensus of the authors was to adopt the following anchors: 1 = “Ninguna o rara vez,” 2 = “Pocas veces,” 3 = “Algunas veces,” 4 = “Bastantes veces,” and 5 = “Todas o casi todas las veces”.

The Spanish version of the GEM used in this study may not be entirely suitable for other Spanish-speaking contexts. Therefore, the appropriateness of the GEM should be considered in relation to the cultural context of the group workers using it.

Quantitative findings

There were 51 adult group participants rated with the measure. As seen in Table 1, engagement was high for all group members, a mean of 3.76 of 5.00 (mean standard deviation was.80). In three cases, all participants were rated with the highest rating (items 15-17). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was.94. As seen in Table 1, the Cronbach’s alpha if the item was deleted remained high, suggesting that no item should be deleted.

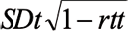

The standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated using the formula:

where SDt is the standard deviation of the test scores and rtt the reliability coefficient (Anastasi, 1988). In this study, the test score is the summed score of the engagement measure. The standard deviation of the test score was 15.28 and the number under the square root is 1 –.94, which is.06. Using the formula above, the SEM of the engagement measure is 3.74. Considering the theoretical range of scores on this version of the GEM is 27 to 135, a SEM of 3.74 is very low. The reliability and SEM findings are similar to studies that have used the English-language versions of the GEM (27– and 37-item versions). Cronbach alphas in the studies across multiple samples have averaged at.93 (Brave Heart et al., 2020; Chovanec, 2012; Chovanec & Roseborough, 2017; Levenson et al., 2009; Macgowan, 1997, 2000a; Macgowan & Levenson, 2003; Prado et al., 2006).

|

Table 1. Item Analysis of the Spanish GEM |

|||

|

Item |

Mean |

SD |

Alpha if Item deleted |

|

1. El participante llega puntual o antes de empezar. |

4.82 |

0.71 |

0.94 |

|

2. El participante se queda hasta el final de las sesiones o se va sólo por razones importantes. |

5.00 |

0.00 |

0.94 |

|

3. El participante no tiene prisa por irse. |

4.47 |

0.99 |

0.94 |

|

4. El participante contribuye hablando en el grupo (ni mucho, ni poco). |

3.82 |

1.20 |

0.94 |

|

5. El participante parece seguir y entender lo que los otros están diciendo. |

4.76 |

0.55 |

0.94 |

|

6. El participante responde conscientemente a lo que todos están diciendo (No solo a uno o dos). |

4.02 |

1.14 |

0.94 |

|

7. El participante interactúa verbalmente con los otros participantes en los temas relacionados con el propósito del grupo. |

4.02 |

1.07 |

0.94 |

|

8. El participante participa en los proyectos/ las actividades del grupo. |

4.71 |

0.58 |

0.94 |

|

9. El participante sigue la guía del facilitador (por ejemplo, sigue lo que el facilitador del grupo propone, quiere que el grupo se involucre en las actividades sugeridas por el facilitador). [Los participantes pudieran a veces cuestionar la guía/dirección del facilitador del grupo. Las cuestiones bien pensadas y constructivas están bien.] |

4.86 |

0.35 |

0.94 |

|

10. El participante muestra entusiasmo al tener contacto con el facilitador (ejemplo: demuestra interés en el facilitador, está interesado en hablar con el facilitador). |

4.49 |

0.78 |

0.94 |

|

11. El participante apoya el trabajo que el facilitador está haciendo con los otros participantes (ejemplo: se mantiene en el tema o amplía la discusión). |

4.37 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

|

12. Al participante le caen bien y le importan los demás participantes del grupo. |

4.67 |

0.55 |

0.94 |

|

13. El participante ayuda a otros participantes del grupo a mantener buenas relaciones entre ellos (ejemplo: anima a los participantes a trabajar en los problemas del grupo, parando los argumentos contraproducentes entre participantes y animando a los participantes del grupo, etc.). |

3.78 |

1.14 |

0.94 |

|

14. El participante habla (anima) a los demás para ayudarlos y focalizarlos en sus problemas. |

3.43 |

1.15 |

0.94 |

|

15. El participante expresa desaprobación constante sobre el horario de las sesiones. [Esto se refiere a expresiones de desaprobación después de que este asunto haya sido resuelto por los otros participantes del grupo.] |

5.00* |

0.00 |

0.94 |

|

16. El participante expresa desaprobación constante sobre el número de sesiones. [Esto se refiere a expresiones de desaprobación mucho después de que este asunto haya sido resuelto por los otros participantes del grupo.] |

5.00* |

0.00 |

0.94 |

|

17. El participante expresa desaprobación constante sobre lo que hacen juntos en las reuniones. [Esto se refiere a expresiones de desaprobación mucho después que este asunto haya sido resuelto por los otros participantes del grupo.] |

5.00* |

0.00 |

0.94 |

|

18. El participante analiza los problemas y los trabaja por partes. |

4.39 |

0.64 |

0.94 |

|

19. El participante hace un esfuerzo por alcanzar sus metas particulares. |

4.63 |

0.75 |

0.94 |

|

20. El participante aporta soluciones para sus problemas específicos. |

4.06 |

1.01 |

0.94 |

|

21. El participante trata de entender las cosas que hace. |

4.71 |

0.86 |

0.94 |

|

22. El participante revela sentimientos que ayudan a entender los problemas. |

3.55 |

1.29 |

0.94 |

|

23. El participante habla (anima) a los demás para ayudarlos a enfocarse en sus problemas. [Para obtener una puntuación alta en este ítem, la oferta de ayuda no necesita ser recibida por el otro participante del grupo. El participante no debe ser responsabilizado por el comportamiento de otros participantes.] |

3.29 |

1.14 |

0.93 |

|

24. El participante habla (anima) a los demás para ayudarlos a concretar sus problemas. [Para obtener una puntuación alta en este ítem, la oferta de ayuda no necesita ser recibida por el otro participante del grupo. El participante no debe ser responsabilizado por el comportamiento de otros participantes.] |

3.16 |

1.16 |

0.93 |

|

25. El participante habla (anima) a los demás a encontrar maneras para ayudarlos a trabajar constructivamente en resolver sus problemas. [Para obtener una puntuación alta en este ítem, la oferta de ayuda no necesita ser recibida por el otro participante del grupo. El participante no debe ser responsabilizado por el comportamiento de otros participantes.] |

3.18 |

1.14 |

0.93 |

|

26. El participante reta constructivamente a los demás en un esfuerzo por resolver sus problemas. [Para obtener una puntuación alta en este ítem, la oferta de ayuda no necesita ser recibida por el otro participante del grupo. El participante no debe ser responsabilizado por el comportamiento de otros participantes.] |

2.75 |

1.40 |

0.94 |

|

27. El participante ayuda a los demás a alcanzar el propósito del grupo. [Para obtener una puntuación alta en este ítem, la oferta de ayuda no necesita ser recibida por el otro participante del grupo. El participante no debe ser responsabilizado por el comportamiento de otros participantes.] |

3.57 |

1.10 |

0.94 |

|

Mean |

3.76 |

0.80 |

0.94 |

|

Note. SD = Standard Deviation. For a copy of the GEM in Spanish, please contact the first author. |

|||

The GEM as part of evidence-based practice in Spanish countries

The Spanish GEM may be used as part of EBGW as it incorporates the best available evidence into practice. The GEM can be used as a measurement-based approach to group work practice (Koementas-de Vos et al., 2022; Macgowan, 2003, 2006b). Cultural adaptations in evidence-based practice (EBP) requires rigorous scientific work that may include not only changes that are culturally syntonic with the geographical area where the program will be implemented, but also the accurate translation of materials so they are relevant to the target population, among other changes (Elliott & Mihalic, 2004; Mejia et al., 2017). Given the interest in recent years in EBP worldwide, it is important to provide the most accurate translation of materials.

In the Spanish Americas, EBP began to develop about thirty years ago (Cabrera & Pardo, 2019; Quant-Quintero & Trujillo-Lemus, 2014). The principal shift in mental health services was driven by the Caracas Declaration established in the Regional Conference for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Services in 1990 in Venezuela (Caldas de Almeida, 2013). The declaration called for a change from traditional hospital-based care to community-based mental health services that included scientific knowledge for treatment (Caldas de Almeida, 2013). As a result, there was an increase in research production in Spanish countries. According to a study (Lillo & Martini, 2013) of articles from Spanish-speaking countries in the Web of Knowledge database, Spain produced 54 % of the research and led 44 % of the most influential (cited) studies. According to the same study, Spanish American countries produced 37 % and led 13%. At the same time, the role of systematic reviews and meta-analysis as part of EBP was also recognized (Sánchez-Meca et al., 2011).

With the growth, came challenges with incorporating best evidence into practice, which includes using reliable measures to assess and advance the helpfulness of group work. Spanish countries have the same concerns as elsewhere when it comes to EBP, including lack of time, lack of incentives, and limited knowledge to evaluate scientific quality (Arnau-Sabatés et al., 2021; Badenes-Ribera et al., 2017; Bonilla Campos & Badenes-Ribera, 2017; Hernández et al., 2020; Horigian et al., 2016). There are promising practices that can help. As noted elsewhere (Macgowan, 2008; Macgowan & Vakharia, 2016), a comprehensive approach to promoting EBP is needed at the organization level (a culture of evaluation and research mindedness), in education that provides trainings and courses in evidence-based practice, and in practice with the development and availability of culturally appropriate, reliable, and valid measures. This paper provides a theoretical and empirically based measure of engagement for group work for Spanish speaking populations as part of EBGW. In addition, it is important for group leaders (or facilitators) to adopt a broad view, not only into the dynamics of families, but also of how a group is formed. It must consider the factors of research and practice to ensure the success of a group intervention (Macgowan & Canizares, 2023).

Summary, limitations, and conclusion

This is the first empirical test of a measure of engagement originally developed in English, for Spanish used in Spain. The process of translation was careful and methodical, and the measure had high internal consistency with a low standard error of measurement. With the richness of the Spanish language and its variants across the world, the version developed and tested in this paper may need further adaptation elsewhere. Furthermore, with a small sample and no additional measures available to assess how the GEM performed against other measures, the validity of the version developed in this study could not be examined. Further studies with larger samples that would allow factor analysis and the use of other measures that could serve as tests of validity, could help further empirically validate the measure, as done with the English version (Macgowan, 2006a). The GEM offers a tool for group leaders to measure and understand the connections among group members. This tool helps both leaders and members to identify and appreciate the presence and richness of these connections, thereby enhancing the overall benefits of group work. Overall, in the context of EBGW, the Spanish GEM can help advance the measurement of important connections in the group, strengthening the effectiveness of group work and their impact in improving the life of participating families in Spanish countries.

Contributions

|

Contributions |

Authors |

|

Conception and design of the work |

Author 1, 2 |

|

Document search |

Author 1, 2, 3 |

|

Data collection |

Author 1, 2, |

|

Data analysis and critical interpretation |

Author 1, 2, 3 |

|

Version review and approval |

Author 1, 2, 3 |

Funding

The authors deeply appreciate the collaboration with Social and Educational Training and Research Group (GIFES) at the University of the Balearic Islands, Palma. The authors also thank Professor Andrés Arias Astray for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. A portion of this paper was completed while the first author was a Fulbright Scholar in Spain, a program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State and the Spanish Fulbright Commission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest, and data presented in the paper are not false or manipulated.

Bibliographic References

Alldredge, C. T., Burlingame, G. M., Yang, C., & Rosendahl, J. (2021). Alliance in group therapy: A meta-analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 25(1), 13-28.

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing (6th ed.). Macmillan.

Arnau-Sabatés, L., Jariot-Garcia, M., & Sala-Roca, J. (2021). Evaluation and research instruments in social pedagogy. Journal of Research in Social Pedagogy (37), 17-19.

Badenes-Ribera, L., Frías-Navarro, D., & Bonilla-Campos, A. (2017). Un estudio exploratorio sobre el nivel de conocimiento sobre el tamaño del efecto y meta-análisis en psicólogos profesionales españoles [Effect size and meta-analysis in Spanish professional psychologists]. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 7, 111-122.

Bonilla Campos, A., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2017). Barreras percibidas por los psicólogos profesionales españoles para una Práctica Basada en la Evidencia. European Journal of Child Development, Education and Psychopathology, 5.

Brave Heart, M. Y. H., Chase, J., Myers, O., Elkins, J., Skipper, B., Schmitt, C., Mootz, J., & Waldorf, V. A. (2020). Iwankapiya American Indian pilot clinical trial: Historical trauma and group interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 57, 184-196.

Burlingame, G. M., & Jensen, J. L. (2017). Small Group Process and Outcome Research Highlights: A 25-Year Perspective. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 67, S194-S218.

Cabrera, P. A., & Pardo, R. (2019). Review of evidence based clinical practice guidelines developed in Latin America and Caribbean during the last decade: An analysis of the methods for grading quality of evidence and topic prioritization. Global Health, 15, 14.

Caldas de Almeida, J. M. (2013). Mental health services development in Latin America and the Caribbean: achievements, barriers and facilitating factors. Int Health, 5, 15-18.

Chovanec, M. G. (2012). Examining Engagement of Men in a Domestic Abuse Program from Three Perspectives: An Exploratory Multimethod Study. Social Work With Groups, 35, 362-378.

Chovanec, M. G., & Roseborough, D. (2017). Examining Rates of Engagement over Time with Court-Ordered Men in a Domestic Abuse Treatment Program. Social Work with Groups, 40, 350-363.

Dyer, J., Kaufman, R., Cabrera, N., Fagan, J., & Pearson, J. (2015). FRPN Research Measure: Fathers’ Engagement (English and Spanish Versions Available). https://www.frpn.org/

Elliott, D. S., & Mihalic, S. (2004). Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prevention Science, 5, 47-53.

Erkut, S. (2010). Developing Multiple Language Versions of Instruments for Intercultural Research. Child Development Perspectives, 4, 19-24.

Estrada, Y., Lee, T. K., Huang, S., Tapia, M. I., Velazquez, M. R., Martinez, M. J., Pantin, H., Ocasio, M. A., Vidot, D. C., Molleda, L., Villamar, J., Stepanenko, B. A., Brown, C. H., & Prado, G. (2017). Parent-Centered Prevention of Risky Behaviors Among Hispanic Youths in Florida. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 607-613.

Gomila, M. A., Pascual, B., Amer, J., & Orte, C. (2023) Intervenciones socioeducativas familiares en entornos escolares y comunitarios. Aula abierta, 52, 185-193.

Guillén, F., & Martínez-Alvarado, J. R. (2014). Escala de compromiso deportivo: una adaptación de la Escala de Compromiso en el Trabajo de Utrecht (UWES) para ambientes deportivos. Universitas Psychologica, 13.

Hernández, C. R., Rosario-Hernández, E., & Lorenzo Ruiz, A. (2020). Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala para una Práctica Profesional Basada en la Evidencia en una Muestra de Psicólogos Clínicos en la República Dominicana. Revista Caribeña de Psicología, 4, 204-216.

Horigian, V. E., Espinal, P. S., Alonso, E., Verdeja, R. E., Duan, R., Usaga, I. M., Perez-Lopez, A., Marin-Navarrete, R., & Feaster, D. J. (2016). Readiness and barriers to adopt evidence-based practices for substance abuse treatment in Mexico. Salud Mental, 39, 77-84.

Hulin, C. L. (1987). A Psychometric Theory of Evaluations of Item and Scale Translations – Fidelity across Languages. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18, 115-142.

Jacobs, P., Estrada, Y. A., Tapia, M. I., Teran, A. M. Q., Tamayo, C. C., Garcia, M. A., Trivino, G. M. V., Pantin, H., Velazquez, M. R., Horigian, V. E., Alonso, E., & Prado, G. (2016). Familias Unidas for high risk adolescents: Study design of a cultural adaptation and randomized controlled trial of a US drug and sexual risk behavior intervention in Ecuador. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 47, 244-253.

Koementas-de Vos, M. M. W., van Dijk, M., Tiemens, B., de Jong, K., Witteman, C. L. M., & Nugter, M. A. (2022). Feedback-informed Group Treatment: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences and Needs of Patients and Therapists. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 72, 193-227.

Levenson, J. S., & Macgowan, M. J. (2004). Engagement, denial and treatment progress among sex offenders in group therapy. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16, 49-63.

Levenson, J. S., Macgowan, M. J., Morin, J. W., & Cotter, L. P. (2009). Perceptions of sex offenders about treatment: Satisfaction and engagement in therapy. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 21, 35-56.

Levin, K. G. (2006). Involuntary clients are different: Strategies for group engagement using individual relational theories in synergy with group development theories. Groupwork, 16, 61-84.

Lillo, S. n., & Martini, N. (2013). Principales Tendencias Iberoamericanas en Psicología Clínica. Un Estudio Basado en la Evidencia Científica. Terapia Psicológica, 31, 363-371.

Lo Coco, G., Gullo, S., Albano, G., Brugnera, A., Flückiger, C., & Tasca, G. A. (2022). The alliance-outcome association in group interventions: A multilevel meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90, 513-527.

Macgowan, M. J. (1997). A measure of engagement for social group work: The Groupwork Engagement Measure (GEM). Journal of Social Service Research, 23, 17-37.

Macgowan, M. J. (2000a). Evaluation of a measure of engagement for group work. Research on Social Work Practice, 10, 348-361.

Macgowan, M. J. (2000b). Prefacio. In G. Burford, J. Pennell, & S. MacLeod (Eds.), Manual para coordinadores y comunidades: Organización y práctica de la toma de decisiones de grupos familiares (Manual for Coordinators and Communities: The organization and practice of family group decision making [1995, August]). Memorial University of Newfoundland, School of Social Work.

Macgowan, M. J. (2003). Increasing engagement in groups: A measurement based approach. Social Work with Groups, 26, 5-28.

Macgowan, M. J. (2006a). The Group Engagement Measure: A review of its conceptual and empirical properties. Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery, 1, 33-52.

Macgowan, M. J. (2006b). Measuring and increasing engagement in substance abuse treatment groups: Advancing evidence-based group work. Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery, 1, 53-67.

Macgowan, M. J. (2008). A guide to evidence-based group work. Oxford University Press.

Macgowan, M. J. & Arias Astray, A. (2024). Trabajo en grupo basado en evidencias. En S Segado Sánchez Cabezudo & A. Arias Astray (Eds.). Modelos de trabajo social con grupos. Nuevas perspectivas y nuevos contextos (pp. 241-258). Aranzadi.

Macgowan, M. J., & Cañizares, C. (2023). La formación de grupos basada en la evidencia para el trabajo con familias. In C. O. Socias, M. B. P. Barrio, & L. Sánchez-Prieto (Eds.), La formación de los profesionales en programas de educación familiar: claves para el éxito (pp. 131-151). Octaedro.

Macgowan, M. J., & Hanbidge, A. S. (2022). Best practices in social work with groups: Foundations. In L. Rapp-McCall, K. Corcoran, & A. Roberts (Eds.), Social Workers’ Desk Reference (4th ed., pp. 661-669). Oxford.

Macgowan, M. J., & Levenson, J. S. (2003). Psychometrics of the Group Engagement Measure with male sex offenders. Small Group Research, 34, 155-169.

Macgowan, M. J., & Newman, F. L. (2005). The factor structure of the Group Engagement Measure. Social Work Research, 29, 107-118.

Macgowan, M. J., & Vakharia, S. P. (2016). Evidence based practice: Challenges and opportunities in the global context. In M. Chakrabarti, D. Sidhva, & G. Palattiyil (Eds.), Social Work in a Global Context: Issues and Challenges (pp. 39-56). Taylor & Francis.

Magallares, A., Graffigna, G., Barello, S., Bonanomi, A., & Lozza, E. (2017). Spanish adaptation of the Patient Health Engagement scale (S.PHE-s) in patients with chronic diseases. Psicothema, 29, 408-413.

Mañas-Rodríguez, M. Á., Alcaraz-Pardo, L., Pecino-Medina, V., & Limbert, C. (2016). Validation of the Spanish version of Soane’s ISA Engagement Scale. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 32, 87-93.

Mejia, A., Leijten, P., Lachman, J. M., & Parra-Cardona, J. R. (2017). Different Strokes for Different Folks? Contrasting Approaches to Cultural Adaptation of Parenting Interventions. Prevention Science, 18, 630-639.

Morcillo-Martínez, A., Infantes-Paniagua, Á., García-Notario, A., & Contreras-Jordán, O. R. (2021). Validación de la Versión Española de la Escala de Compromiso Académico para Educación Primaria. RELIEVE – Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 27.

Orte, C., Pascual, B., & Sánchez-Prieto, L. (Eds.). (2023). La formación de los profesionales en programas de educación familiar: claves para el éxito Octaedro.

Orte, C., Oliver, J. L., Amer, J., Vives, M., & Pozo, R. (2019). Universal Prevention. Evaluation of the effects of the universal Spanish Strengthening Families Program in elementary schools and high schools (SFP-U 11-14) Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34, 19-30.

Plasse, B. R. (2000). Components of engagement: Women in a psychoeducational parenting skills group in substance abuse treatment. Social Work with Groups, 22, 33-50.

Prado, G., Pantin, H., Schwartz, S. J., Lupei, N. S., & Szapocznik, J. (2006). Predictors of engagement and retention into a parent-centered, ecodevelopmental HIV preventive intervention for Hispanic adolescents and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 874-890.

Quant-Quintero, D. M., & Trujillo-Lemus, S. (2014). Psicología clínica basada en la evidencia y su impacto en la formación profesional, la investigación y la práctica clínica. Revista Costarricense de Psicología, 33, 123-136.

Ramos-Diaz, E., Rodriguez-Fernandez, A., & Revuelta, L. (2016). Validation of the Spanish Version of the School Engagement Measure (SEM). Span J Psychol, 19, E86.

Riera i Romaní, J. (2011) Las familias y sus relaciones con la escuela y la sociedad frente al reto educativo, hoy. Educación Social, 49, 11-24.

Sánchez-Meca, J., Marín-Martínez, F., & López-López, J. A. (2011). Meta-análisis e Intervención Psicosocial Basada en la Evidencia [Meta-analysis and Evidence-Based Psychosocial Intervention]. Psychosocial Intervention, 20, 95-107.

Sireci, S. G., Yang, Y. W., Harter, J., & Ehrlich, E. J. (2006). Evaluating guidelines for test adaptations – A methodological analysis of translation quality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 557-567.

Tapia, M. I., Schwartz, S. J., Prado, G., Lopez, B., & Pantin, H. (2006). Parent-centered intervention: A practical approach for preventing drug abuse in Hispanic adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice, 16, 146-165.

Tetley, A., Jinks, M., Huband, N., & Howells, K. (2011). A systematic review of measures of therapeutic engagement in psychosocial and psychological treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 927-941.

Torío López, S. (2017). How to educate? Are we doing it well? Contributing to the on going debate in the literature about the Optimum parental educational style. Journal of Research in Social Pedagogy, (29), 9-17.

Waites, C., Macgowan, M. J., Pennell, J., Carlton-LaNey, I., & Weil, M. (2004). Increasing the cultural responsiveness of Family Group Conferencing. Social Work, 49, 291-300.

Wood, P., Moenne, G., Arteaga, C., Larraechea, R., Dosal, F., José Del Solar, M., Klempau, R., de Aguirre, J., Becerra, M., & Besio, C. (2018). Medición 2018 Engagement. Equipo Circular HR Fundación Chile.

HOW TO CITE THE ARTICLE

|

Macgowan, M. J., Tapia, M. I. & Cañizares, C. (2025). Preliminary test of a Spanish version of the group engagement measure to advance evidence based practice in groups. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 46, 91-102. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2025.46.05 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

Mark J. Macgowan. Professor, School of Social Work & Associate Dean, Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC5-513, Miami, FL 33199 Email: Macgowan@fiu.edu Maria Isabel Tapia. Senior Research Associate, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, 5030 Brunson Drive, Suite 440D, Coral Gables, Florida 33146. Email: m.tapia1@med.miami.edu Catalina Cañizares. Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Applied Psychology, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, 246 Greene Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003. Email: cc9082@nyu.edu |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

MARK J. MACGOWAN https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8505-5515 Professor Mark Macgowan is Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Professor of Social Work at Florida International University in Miami. His teaching, research, and practice focuses on evidence-based group work and improving psychosocial response to mass casualty events. His books include “Guide to Evidence-Based Group Work,” “Group Work Research” (both Oxford University Press), “Evidence-Based Group Work in Community Settings” and “IASWG Standards for Social Work with Groups” (both Taylor & Francis) and co-editor of the upcoming “International Handbook on Social Work with Groups” (Routledge Press). Professor Macgowan has led research projects related to psychosocial response to mass casualty events. He has received international recognition, including two Fulbright awards to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and at the University of Murcia, Spain. MARIA ISABEL TAPIA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0566-9497 Dr. Tapia is a licensed professional psychotherapist with over 25 years of experience of conducting research studies at the University of Miami and private practice with clients. She has dedicated her career to the prevention and treatment of adolescent substance use, behavioral problems, sexual risk behaviors and mental health with Hispanic families. In her role as a senior researcher and clinical expert of evidence-based practices, she has trained and supervised agencies and therapists in the U.S., Latin America, and Europe. She has participated in groundbreaking, NIH-funded behavioral clinical trials, and has authored several articles and book chapters in minority HIV, drug abuse, mental health, and LGBTQ+ issues taking into consideration the cultural context and functioning of the Hispanic family. She was the recipient of a fellowship grant from The Center of Human Rights & Social Justice, to conduct research with the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender population. CATALINA CAÑIZARES https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-5205 Dr. Catalina Cañizares is a postdoctoral researcher at New York University specializing in adolescent mental health and suicide prevention. Her research combines data science and prevention science, focusing on developing machine learning algorithms to predict suicide attempts and advancing culturally tailored interventions. She is actively working on projects, including testing machine learning models across national datasets and evaluating evidence based programs for Latin American adolescents. Dr. Cañizares aims to enhance early suicide risk identification and inform evidence-based mental health policies for Spanish speakers. |