eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2025.47.11

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

Urban artistic expressions for socio-educational work

on gender-based violence

Expresiones artísticas urbanas para el trabajo socioeducativo

de las violencias de género

Expressões artísticas urbanas para um trabalho socioeducativo

sobre a violência de género

Miguel Ángel BURÓN-VIDAL  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5721-4614

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5721-4614

Noemi LAFORGUE-BULLIDO  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3690-6077

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3690-6077

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED)

Received date: 13.III.2024

Reviewed date: 01.V.2024

Accepted date: 21.III.2025

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Miguel Ángel Burón Vidal: Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación I, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Calle Juan del Rosal, 14 Moncloa. Segunda Planta, despacho 2.14. E-mail: ma.buron@edu.uned.es

|

KEYWORDS: Gender discrimination; urban culture; music; adolescence; informal education. |

ABSTRACT: The role of socialization contexts such as school, family or peer group in the disparate construction of gender has been widely addressed. However, in recent decades, the social science gaze and public debate has been clustering around other forms of learning that influence this construction. One of the areas that stands out for its constant appearance in these debates is the urban arts, often accused of generating violence in the younger population. This article will delve into this relationship, as well as the potential of these cultural expressions to question gender violence. For this reason, 15 educational figures who incorporate Rap music in different socio-educational activities with adolescents were interviewed to try to clarify: the most common situations of gender violence in these contexts; their perception of the role of this genre with respect to this violence; and the potential it presents for questioning and transforming the situation. Some of the violence pointed out has to do with the presumption of masculinity of this genre, with the lack of female referents in it or with the existence of lyrics that reproduce misogynist ideas. However, the people interviewed consider that this musical genre promotes machismo like any other cultural manifestation immersed in a patriarchal system. Furthermore, they consider that, if well directed, socio-educational intervention through rap music has the potential to work on gender violence with adolescents, such as: its appeal to this population, its ease of use, the possibilities it offers to promote references that go beyond hegemonic masculinity/femininity, the importance it gives to personal experience and the ease with which it encourages conversations that are difficult to have in other socio-educational contexts. |

|

PALABRAS CLAVE: Discriminación de género; cultura urbana; música; adolescencias; educación informal. |

RESUMEN: El papel de los contextos de socialización como la escuela, la familia o el grupo de iguales respecto a la construcción dispar del género ha sido un aspecto ampliamente abordado. No obstante, en las últimas décadas la mirada de las ciencias sociales y el debate público se está agrupando alrededor de otras formas de aprendizaje que influyen en esta construcción. Uno de los ámbitos que destaca por su constante aparición en estos debates es el de las artes urbanas, acusadas a menudo de generar esa violencia en la población más joven. En el presente artículo se va a ahondar en esta relación, así como en las potencialidades que pueden tener estas expresiones culturales para cuestionar la violencia de género. Para ello, se entrevistó a 15 figuras educativas que incorporan la música Rap en diferentes actividades socioeducativas con adolescencias para tratar de esclarecer: las situaciones de violencia de género más comunes en estos contextos; su percepción acerca del papel de este estilo musical respecto a esta violencia; y los potenciales que presenta para cuestionar y transformar la situación. Algunas de las violencias señaladas tienen que ver con la presunción de masculinidad de este género, con la falta de referentes femeninos en el mismo o con la existencia de letras que reproducen ideas misóginas. No obstante, las personas entrevistadas consideran que este estilo musical promueve el machismo como cualquier otra manifestación cultural inmersa en un sistema patriarcal. Además, consideran que, bien dirigida, la intervención socioeducativa por medio del Rap cuenta con potencialidades para trabajar la violencia de género con adolescencias como: el atractivo que supone para esta población, su fácil manejo, la posibilidades que ofrece para propiciar referentes que se salen de la masculinidad/feminidad hegemónica, la importancia que concede a la experiencia personal o la facilidad con la que propicia conversaciones que difícilmente se dan en otros contextos socioeducativos. |

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Discriminação de género; cultura urbana; música; adolescência; educação informal. |

RESUMO: O papel dos contextos de socialização, como a escola, a família ou o grupo de pares, na construção díspar do género tem sido amplamente abordado. No entanto, nas últimas décadas, o olhar das ciências sociais e o debate público têm vindo a aglutinar-se em torno de outras formas de aprendizagem que influenciam essa construção. Uma das áreas que se destaca pelo seu constante aparecimento nestes debates é a das artes urbanas, frequentemente acusada de gerar esta violência na população mais jovem. Este artigo irá aprofundar esta relação, bem como o potencial destas expressões culturais para questionar a violência de género. Para tal, foram entrevistadas 15 figuras educativas que incorporam a música Rap em diferentes actividades socioeducativas com adolescentes, de forma a tentar clarificar: as situações de violência de género mais comuns nestes contextos; a sua perceção do papel deste estilo musical relativamente a esta violência; e o potencial que apresenta para questionar e transformar a situação. Algumas das violências apontadas têm a ver com a presunção de masculinidade deste género musical, com a ausência de referentes femininos ou com a existência de letras que reproduzem ideias misóginas. No entanto, os entrevistados consideram que esse estilo musical promove o machismo como qualquer outra manifestação cultural imersa em um sistema patriarcal. Além disso, consideram que, se bem orientada, a intervenção socioeducativa através do Rap tem potencialidades para trabalhar a violência de género com adolescentes, tais como: a sua atratividade para esta população, a sua facilidade de utilização, as possibilidades que oferece para promover referências que vão para além da masculinidade/feminilidade hegemónica, a importância que dá à experiência pessoal e a facilidade com que incentiva conversas difíceis de ter noutros contextos socioeducativos. |

1. Introduction

The way in which ideas underpinning gender inequality are reproduced has been extensively studied in the family context (González Barea and Rodríguez Marín, 2020; Alemany Arrebola et. al., 2019), in educational institutions (Bas Peña, 2015) and in models of attraction and first love relationships (Sánchez Gómez et al., 2015; Aubert Simon et al., 2010). With increasing importance, the focus of research has been extended to the relationship between gender violence and urban culture, as well as the impact of this relationship on the adolescent population (Garcés-Montoya and Acosta-Valencia, 2023, Hormigos-Ruiz et al., 2018), which is the focus of this article.

Since the dynamics of class confrontation with dominant cultures by extra-institutional identities in Western cities in the second half of the twentieth century (Hall and Jefferson, [1993] 2014), youth cultures have been revealing the complexity of their ways of adhering to, creating and consuming aesthetic expressions. Dissidence and identity recreations have coexisted with the decontextualized imitation and hybridization of other artistic forms, with different degrees of absorption by the market or subordination to the hegemonic framework (Álvarez García et al., 2024). It can be agreed that the practices –with roots in the Afro-diaspora– included in Hip-Hop culture since the 80s of the last century correspond to the starting point of what are here qualified as urban arts (Ballarín, 2019). Specifically, Rap would be the diverse musical genre that emerged from the youthful effervescence that challenged frustration through graffiti, parties and other conflictual aesthetics (Marchant, 2024) in stigmatized neighborhoods during the 1970s (Ladrero, 2016). Their different expressions have been significantly eloquent in reflecting the power dynamics and contradictions of the most idealized and innocuous social narratives (Mustaffa, 2022).

These artistic expressions are often judged as promoting messages that foster women’s inequality (Johnson, et. al., 2017); however, as noted above, the interaction between the protagonists of these cultural phenomena and the patriarchal social structure is considered here to respond to more complex and by no means unidirectional dynamics Taking an intersectional perspective, it is possible to recognize the way in which these manifestations are permeated by structural machismo, in interaction with other forms of domination (Hill Collins and Bilge, 2019). From the perspective and praxis of critical pedagogies we have considered some socio-educational actions that can incorporate their potential to identify and question gender-based violence, taking into account some of the active transforming levers in their own practices (Hunt, 2018; Muhammad, 2015).

2. Justification and Objectives

Many educational spaces have realized the appeal of these forms of expression for adolescents and how they can serve to challenge gender stereotypes and violence. Both rap and urban dance are significant models for the construction of dissident identities and the creation of alternative symbolic spaces of belonging –even if the ephemeral nature of their duration and modes of connection have been described as weak sociability (López et al., 2021)–. These have proposed verbal and bodily discourses that facilitate empowerment for vulnerable and excluded adolescents (Adjapong and Emdin, 2015).

Thus, it has been argued that Rap can be a form of resistance against patriarchal structures, giving voice to women’s experiences and struggles (Muhammad, 2015; Pégram, 2015), as demonstrated by multiple artists who denounce gender inequality and violence in their lyrics. Dance, for its part, often challenges traditional gender norms and empowers dancers to explore and question concepts of masculinity and femininity. Research such as that of Casu (2024) has highlighted the importance of urban dance communities as spaces where diversity is promoted and harmful gender dynamics are challenged.

However, the interpretation of urban artistic expressions can be more ambiguous. There is no shortage of disruptive manifestations that draw attention to violent discourses that, if the contexts that explain the codes of artists and public are not considered (Cunningham and Rious, 2015), are often denigrated as dangerous arts. Some of these expressions of Hip-Hop culture or various urban dances may reproduce hegemonic values of patriarchal states: fetishization of women, exaltation of male strength as a desirable value, materialism and misogyny (Haaken et al., 2012). These ideas do not only have negative consequences for women, but also limit the desired masculinity ideology, focusing on characteristics such as physical strength, supposed emotional neutrality or control of their affective-sexual partners (Baxter and Marina, 2008). Such stereotypes may have even greater consequences for racialized women and men, who have historically been ascribed physical, social and relational characteristics that continue in our collective ideologies and are reinforced through various artistic manifestations (Davis, [1981] 2004; hooks, [1994]2001). Concern about these negative effects has encouraged debate about the appropriateness of the use of these artistic expressions in socio-educational contexts.

However, it can be considered that confronting current youth artistic practices as educational tools to prevent gender-based violence means understanding the political dimension of education as a decisive space for democratic practice, construction and questioning (Izquierdo-Montero and Aguado-Odina, 2020). Following Fernández Martorell (2020), politicizing education means prioritizing meaningful questions over given answers, delving into the causes of problems and making visible the hidden curriculum validated by educational policies in relation to its social value.

This paper aims to explore the experience of professionals who incorporate one of these urban arts, rap music, as a socio-educational action strategy. To this end, we analyze their experiences and perceptions about the link between this artistic expression and gender-based violence, as well as its potential to confront this type of oppression. With this objective in mind, perspective offered by the conjunction of critical pedagogies and pedagogies of rupture (Garcés-Montoya and Acosta-Valencia, 2023), with the understanding of the interdependence of gender violence with other axes of domination (Ugena-Sancho, 2023), is adopted here. In this sense, this study is framed within intersectional feminism, which takes into account the centrality of the complexity of interrelationships of oppression/inequality experienced and expressed by adolescent girls through their own technical/creative knowledges (Hill Collins and Bilge, 2019). Thus, in addition to the situated reality of the protagonists of these processes, creation of emancipatory, transformative and non-individualistic educational relationships (Garcés, 2020) and the facilitation of artistic practices with the potential to rename experiences and recompose organisational forms of creative and critical participation (Graham, 2020) become important.

3. Methodology

The complexity and contextual nature of the studied phenomenon oriented this research towards the qualitative paradigm. It is a proposal that is situated within the phenomenological research that seeks to examine the experience of specific subjects around a well-defined fact (Loayza Maturrano, 2020). To this end, 15 in-depth interviews were conducted with educational figures from different contexts. However, although the proposal was not intended to transfer the results to other environments, quality criteria were followed to ensure the rigorousness of the study (Tracy, 2021; Díaz Bazo, 2019): informants were chosen with different demographic characteristics –the sample is diverse in terms of gender, age, origin and links with Rap music– and who worked in different projects order to offer a sufficiently broad diversity of perspectives –community action projects, leisure and free time, social intervention, etc.–; previous position of the researchers was defined –and has been reflected throughout the justification section– as an exercise in transparency –their personal links with Rap music as a means of expression and as an educational tool–; the analysis was illustrated with verbatim interviews to try to avoid over interpretation by the authors; and the relevant ethical procedures were followed to protect the participants and their interests –information was provided about the aims, procedures and possible uses of the research, informed consent was given detailing all the information, a space was provided for the resolution of doubts and the possibility of anonymizing their contributions was offered–. In addition, extra actions were carried out to ensure the adequacy of the analysis to the perception of the interviewees, such as: the manual, complete and immediate transcription of the interviews; the return of the transcriptions to the participants to correct possible transcription errors; and the return of the analysis to the participants to correct possible interpretation errors.

The sample, of an intentional or convenience nature, responded to the following criteria: that they were people working in socio-educational environments with vulnerable adolescents –who suffered some kind of interpersonal or systemic violence–; that they incorporated Rap music as an educational tool in their pedagogical practices; and that gender representation was reflected in the sample. Despite not seeking replicability of the data, but rather an in-depth study of specific experiences, the saturation criterion (Chicharro Merayo, 2003) was followed to decide on the number of interviews to be carried out. In order to gain access to these people, calls were made through the social networks X and Instagram. The interviews were audio-recorded for later transcription and analysis. All participants were informed about the aim of the research and the possible use of the data. For this purpose, an explanatory document was sent to them in advance, together with an informed consent form. Only one participant requested her participation to be anonymized to protect the people with whom she worked. The rest requested to be identified by their personal name or AKA1. Regarding the profile of the interviewees, there were 6 women and 9 men between 24 and 41 years of age. They worked in Spain (n = 9), Mexico (n = 5) and Colombia (n = 1). The type of projects and the age range with which they work can be found in the following table (Table 1):

|

Table 1. Description of the projects and the population they work with |

|

|

Interview code |

Project and population |

|

E01. Álvaro |

Project “Barrios”, a socio-community intervention project through Rap music aimed at children and adolescents in two suburbs of Madrid –Orcasitas and Las Torres de Villaverde–. |

|

E02. Ángel |

— Private center for educational and therapeutic intervention aimed at adolescents with different addiction/behavioral problems, where they receive outpatient or residential care. |

|

E03. Carlos |

— Training and Work Insertion Unit (UFIL) 1.º de mayo for adolescents who have not been promoted in the compulsory education system. |

|

E04. Íñigo |

Project “Barrios”, a socio-community intervention project through Rap music aimed at children and adolescents in two suburbs of Madrid –Orcasitas and Las Torres de Villaverde–. |

|

E05. Danger |

— Secondary schools in Mexico. — Prisons in Mexico for adolescents with custodial sentences for crimes such as homicide or drug trafficking. |

|

E06. Marina |

— Workshop on women’s rights in the world organized by the Women’s Foundation and aimed at the adolescent population. |

|

E07. Skafo Lafaro |

— Workshop for a house-home in Tijuana for unaccompanied migrant children and adolescents. — Workshop on expression through Rap for adolescent women and dissident identities. |

|

E08. Julio |

— Rap workshop for adolescents users of the Centro de Participación e Integración de inmigrantes (CEPI) Hispanic-Dominican immigrant participation and integration centre in Tetuán. — A socio-cultural entertainment project aimed at teenagers in “El Ruedo”, a neighborhood where relocated people live. |

|

E09. Anonymized |

— Programme for the prevention and treatment of truancy in high schools. — Rap workshop in a socio-community action project aimed at adolescents in a suburb of Murcia. |

|

E10. Lucía |

— Rap project that works with children and adolescents who have been part of the armed conflict in Colombia. |

|

E11. Masta Quba |

— Rap expression project aimed at teenage and adult women. |

|

E12. Prince Jaguar |

— Leisure and free time project in a youth space in Catalonia aimed at teenagers. |

|

E13. Vanesa |

— Activity of the youth centers of the Community of Madrid “Dismantling racism” aimed at adolescents with migration experiences. — Leisure and free time activity aimed at adolescent users of youth centers in the Community of Madrid. |

|

E14. Ángel Under Clap |

— Project called “Hip-Hop between cultures”. Experience working with indigenous children in Mexico on the importance of caring for water. |

|

E15. Fémina Fatal |

— Project called “Circuito Abierto” –Open circuit–. Freestyle workshop for teenagers and young people from Ensenada (Tijuana). — Feminoise cypher, improvisation workshop for young women and teenagers. |

The Thematic Content Analysis technique (Morentin Encina et al., 2022) was used for data analysis. In this way we looked for recurring patterns among the discourses of the interviewees while still capturing the diversity of voices and experiences. To facilitate this analysis, the Atlas ti 9.1.7 software, a tool widely used in educational research, was utilized, (Cipollone, 2022). The categorization was carried out through an inductive process, seeking a descriptive and interpretative approach to the study phenomenon (Acosta Faneite, 2023). The categories emerging from the fieldwork, as well as their meanings and frequencies, can be consulted in Table 2:

|

Table 2. List of operationalized categories of analysis |

||

|

Name of the category |

Definition |

Frequency |

|

1. Situations of male violence. |

Situations in which manifestations of male violence occurred in the work with young people through Rap music. |

n = 15 |

|

1.1. Hip-Hop culture as a masculine space. |

Circumstances in which adolescents link Hip-Hop culture as a space exclusively for men. |

n = 6 |

|

1.2. Lack of female role models. |

Occasionally, interviewees pointed out the lack of female role models for the teenage girls involved. |

n = 5 |

|

1.3. Reproduction of sexist ideas. |

Situations where it was recognized that rap music was used by adolescents to reproduce sexist ideas. |

n = 4 |

|

2. Link between Rap music and male violence. |

Occasions in which the educational figures interviewed made reference to the relationship that might exist between Rap music and male violence –in one sense or another–. |

n = 8 |

|

3. Rap music’s potential to work on male violence. |

Strengths identified by the interviewees in Rap music to work on the prevention and treatment of gender-based violence. |

n = 23 |

|

3.1. Potential to challenge gender stereotypes. |

Occasions where interviewees point out the facilities offered by this musical style to challenge gender stereotypes. |

n = 5 |

|

3.2. Potential to address the problem from personal experience. |

Situations in which interviewees named the potential of the musical genre to address gender-based violence using examples from the everyday lives of the adolescents involved. |

n = 4 |

|

3.3. Potential to foster complex dialogues. |

Circumstances in which the ease with which this genre can be used to promote dialogues that normally have no place in socio-educational spaces is mentioned. |

n = 4 |

|

3.4. Potential to generate links from common ground. |

Occasions where the ease of generating social support groups through socio-educational experiences through Rap music is mentioned –this being a protective factor against macho violence–. |

n = 3 |

|

3.5. The playful nature of the experiences. |

Situations in which the playful nature of the experiences carried out through Rap music is mentioned as a potential sensitizer against male violence. |

n = 3 |

|

3.6. Own language |

Circumstances in which it is pointed out that one of the potentials of this musical style to work on male violence is the similarity of the language it uses with the language used by adolescents. |

n = 2 |

|

3.7. Accessibility |

Occasions where the accessibility of Rap music –a genre that does not require extensive knowledge or means to perform– is mentioned as a potential. |

n = 2 |

4. Results

Of the 15 people interviewed, only four worked on projects that specifically address gender-based violence through rap music –Carlos, Marina, Skafo Lafaro and Masta Quba–. Nevertheless, concerns and comments about this issue were present in 12 of the 15 interviews, accumulating 88 entries in total.

Rap music and gender-based violence: experiences and perceptions of the link between the two phenomena

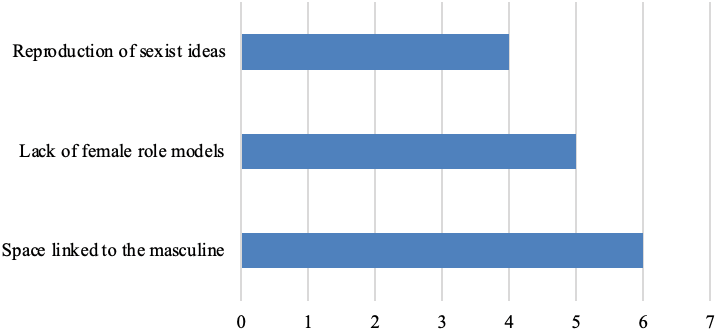

First of all, ten of the interviewees named various situations of more or less subtle gender-based violence in these spaces –see figure 1–:

Figure 1. Situations of gender-based violence in contexts mediated by Rap music.

The most frequently mentioned violence (n = 6) was related to the consideration of Hip-Hop culture as an exclusively male space. Four of the people who mentioned this expression of violence were female rappers who experienced it first-hand as educators and artists. As could be seen, the exclusion of women from the spaces where Rap music is developed was sometimes subtle (n = 3):

“I went into mixed workshops and it was always: one woman and 20 men. So, it was something that I had to prove that I was also at the same level. It was complex because in one way or another I was confronted with the macho environments of the domains” (Skafo Lafaro, 15 June 2021).

However, they noted that on many other occasions opposition to women who choose to express themselves through this medium was much more explicit (n = 3):

“(…) when some girls started coming to the workshop in particular, some of the boys said: this is not for girls, here we are, this is ours” (Íñigo, 5 March 2021).

The arguments used to support this exclusion were that Rap music was learned on the street and that women are not “street”, and that Rap music could not be “taught” –especially when it comes to training initiatives carried out by women–. These beliefs were reflected in the occasions when male participants allowed themselves to explain what Rap music was and how it was made to the female participants, even when they were playing the role of experts (n = 3). Interviewees noted how the presumption of male ownership of Rap impacted on girls’ willingness to participate. In this regard, three respondents argued that girls were less likely to participate in such activities when they were volunteers. Likewise, if they were involved in activities in which they participated as a ‘captive audience’ –where participation is compulsory– they tended to contribute much less actively than their male counterparts.

Another violence mentioned was the lack of female role models in Rap music (n = 5). In this sense, the male educational figures mentioned how they had been discovered by exclusively giving examples of male artists. On the other hand, the female educational figures mentioned how the lack of female referents was something that made it difficult for them to feel legitimized to express themselves through this medium.

The reproduction of sexist ideas through rap music was the third violence named (n = 4). Educational figures interviewed argued that boys and girls were generally attracted to the more commercial and stereotypical image of this music genre, tending to create messages that reproduced gender stereotypes and unequal relationships.

Despite the situations described above, the educational figures interviewed did not consider that there was a direct link between rap music and gender-based violence. Regarding the sexist content of the lyrics of this musical genre, four of the interviewees considered that it only reproduced the existing values in society because “It is music and society is sexist, so the music reflects what is there” (Íñigo, 5 March 2021).

In this sense, one of the participants pointed out that all musical genres, unfortunately, have sexist content, something that they worked on in their organization “Fundación Mujeres”: “what we always said is that it doesn’t matter the musical style. You can have the same artists who contradict themselves in their songs and in the values of their songs” (Marina, 13 July 2021).

Marina also pointed out that from her perspective, the lower representation of women in this musical genre had to do fundamentally with two facts: the gender socialization that limits women to the private space and the social sanction that women suffer when they step out of the logic of femininity.

The potential of Rap music as a medium for working on gender-based violence

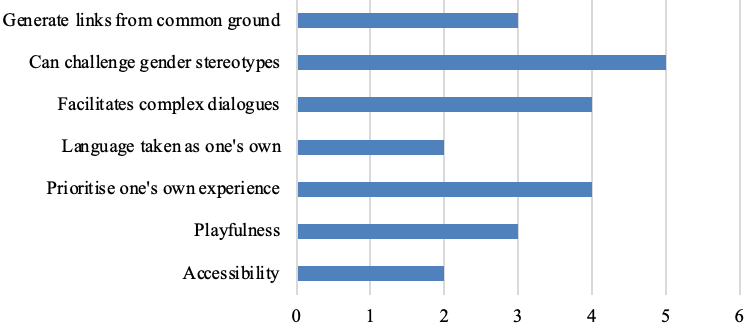

Throughout the interviews, eight of the educational figures mentioned some of the potential of rap music to work on gender-based violence with adolescents –see graph 2–. In this sense, the most frequently mentioned potential was the possibility it offers to break gender stereotypes (n = 5).

Figure 2. Rap music’s potential to work on gender-based violence.

One of the strategies that the educational figures said they used for this purpose was the use of diverse references that questioned these stereotypes. In this way, the idea of women as passive, non-assertive and uninterested in political participation was broken:

So I think that this is another thing about Rap: it involves a lot of strength. It’s like breaking the silence that has been there for years and saying: I’m here. It’s like when people tell us: you look prettier when you’re quiet (…) We’ve already warn: neither quiet nor pretty. We are not here to be an accessory in your house or in your living room (Skafo Lafaro, 15 June 2021).

They claimed to do so using well-known figures, such as famous female rappers and freestylers, but also through their own example, as in this case where male stereotype of the hard man, who objectifies women and hides his emotions, was questioned:

And all of a sudden, they meet a person who is completely different and is himself, self-confident. He’s “nice” because she’s a person who raps, who paints graffiti… It gives them the opportunity to validate other behaviors that nobody has taught them that they are also and that are very nice: that you can be a man and not be macho, be with your partner and hug her, or your friend, that you can give emotional support to your other friend, that you are not objectifying another woman, that you are… well, being an example for them (Prince Jaguar, 1 November 2021).

Another of the most frequently mentioned potentials was that Rap music allows to address issues related to gender-based violence from one’s own experience (n = 4), recognizing daily violence and overcoming the generalist slogans that place gender-based violence as something alien to specific people. As some of the educational figures interviewed pointed out, this musical genre encourages the expression of personal experiences, allowing girls who have suffered violence to name it and find its social explanation:

Girls who had not been able to name a story they had lived 15 years ago and after a month (…) they ended up naming it with all their fierceness and with all their guts, right? As if they were sure that their story is valid, that what they have to say is important (Masta Quba, 1 November 2021).

They also mentioned how this “speaking from personal experience” could lead to moments of reflection on their own attitudes of gender-based violence, in order to deconstruct them. This process of reflection occurred, for example, when they had to write lyrics that addressed the proposed content, but from subjective understanding:

If you make an interesting process and you use Rap as a tool and we are talking about why you behave this way: why am I violent, why am I not violent, why do I reproduce this pattern, this role, what comes from home… And Rap as such to pour out all that is crushing you inside… (Marina, 13 July 2021).

Similarly, the educational figures pointed out that another of the potentials of Rap music was the ease with which it encourages dialogue that is difficult to find in educational spaces (n = 4). In this sense, they pointed out, that as they felt they were in their own space, which promotes personal expression, the girls and boys were open to expressing their ideas on controversial issues. This allowed them to identify what the starting point was and which issues required more work to raise awareness: “It’s cool on the way that they suddenly let you know everything they think to your face and we can identify which values we need to work on” (Julio, 8 June 2021). Also, some felt that these conversations could be redirected towards the idea of the responsibility we have when our voice is going to be heard by other people:

It is very clear that we assume a responsibility as artists and that having a microphone implies that responsibility: you are saying something and what you are saying, and why you are saying it (Skafo Lafaro, 15 June 2021).

Another of the potentialities pointed out (n = 3) was how this musical style allows for the construction of an interpersonal network based on affinities in relation to music or experiences. In this sense, educators such as Marina mentioned how boys and girls who have suffered situations of gender-based violence –either outside or inside their families– can feel reflected in songs that address this issue, transcending identifications such as social class, racialization or territory. She pointed out how at the same time allowed them to overcome emotions such as loneliness or guilt. Similarly, as Masta Quba or Skafo Lafaro mentioned, in the context of non-mixed groups2 the girls shared situations of violence and pain, creating a collective resistance and solidarity against machismo.

On the other hand, three of the participants mentioned the playful nature of Rap as another of the potentials of this musical genre. As Skafo Lafaro explained, its great diffusion and success among young audiences was evidence of its conception as a recreational activity:

And it was quite a fun activity on the one hand, but on the other hand, I think that the objective we set ourselves when we asked for this workshop was achieved, the fact of working on and dealing with equality (Carlos, 17 June 2021).

This playful nature made it possible to address complex issues in a more friendly and attractive way for adolescents:

Methodology as an “excuse”, because I think it is a very positive excuse. To use tools that are more attractive, more connected to the interests of the young public, to be able to get into issues that are tougher (Marina, 13 July 2021).

Finally, awareness-raising against gender-based violence was also mentioned as a potential for adolescents (n = 2) and from a very accessible form of expression (n = 2) in which the participants quickly feel competent, which has an impact on their self-esteem:

I also like to see their progress because I see how they begin maybe not knowing how to rap, and I see how they end up throwing more complex structures, having a performance on stage, or having live shows (Skafo Lafaro, 15 June 2021).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The results of this study show that although the educational figures interviewed identified situations of gender-based violence in the contexts in which they work, they did not attribute the causes to Rap music. In this sense, they pointed out that the connection between this musical genre and gender violence is the same as any social fact inserted in a patriarchal system. This is a similar conclusion to the one drawn by González-Barea and Rodríguez-Marín (2020), who point out how stereotyped femininity is reproduced even in children’s stories and games. Along the same lines, Bas Peña et al. (2014) indicate how the educational system can act as a reproductive medium, but also as a means of preventing sexist ideas. Through the discourse of educational figures involved in the research it can be concluded that this dichotomy is also present in Rap music and that its reproductive/preventive function will depend on how it is used.

In this sense, some of the interviewed persons pointed to the music industry as one of those responsible for this reproduction, which coincides with what is defended by authors such as Vito (2019) and Haaken et al. The music industry tries to make its products more attractive to the general public by conforming to mainstream ideas. This is why Kim and Pulido (2013) argue that the use of Rap music should be the one targeted rather than the musical style itself. Another key insight of this research has to do with what one of the participants said. She argued that when certain cultural manifestations are criticized and the machismo of others is overlooked, this leads to a certain racist and classist bias that tries to place the responsibility for very broad social problems on a single sector of society –a point also made by authors such as Jacobson (2015)–.

Another relevant result of this study is the potential of Rap music to raise awareness about male violence, as identified by the educational figures. One of them is its suitability for strategically approaching a subject that presents a certain complexity. As they point out, this suitability has to do with the playful nature of the activity, linked to the musical tastes of some adolescents; with the accessibility of this artistic expression compared to others that require greater technical knowledge; with the facility it offers to generate dialogue based on a language that adolescents assume as their own and, therefore, not imposed; and with the possibility it offers to build relationships of trust from a common starting point, especially in the case of the educational figures who also assume this musical style as their own.

Similarly, they identified as potential a number of attributes that have to do with the depth with which this musical style allows gender-based violence to be addressed. One of these attributes is the transgression of gender stereotypes that this musical style allows. As we have seen, Rap music often serves as a reproducer of these stereotypes; however, the educational figures also named situations in which it was used for the opposite, such as, for example, showing kinder and more respectful models of masculinity in an attractive way. These attitudes coincide with what is pointed out by authors such as Bas-Peña (2015), who highlight the importance of training educators to assume attitudes that set an example of masculinities that are diverse and far removed from the model imposed by the patriarchy. In this sense, we believe that new models of femininity are also necessary. Rap can encourage expressions of strong femininity, capable of showing anger, of defending their rights, and that present their personal experience as part of the experiences that make up the public narrative. Likewise, we consider that experiencing the artistic channeling of rage makes it possible to denaturalize pain and aggression, just as the encounter of those who risk their lives confronting gender violence allows for collective expressions that transcend the false individual explanation (Butler, 2021). Its educational facilitation rehearses authentic schools of rage (Belausteguigoitia Rius, 2022) to transgress fragmented impotence and articulate alliances –multiple and diverse– capable of courage, imagination and co-creation.

Finally, another mentioned potentiality is that this musical style allows us to transcend the big slogans by prioritizing the personal story. Thus, when girls and boys become the protagonists of the discourse, they discover how gender violence translates into their daily lives, moving towards the transformation of their own realities. This is, as we have seen, a challenge when their thinking is based on stereotypes and prejudices. However, the educational figures pointed to this challenge as a potential, as the situation allowed them to understand the participants’ starting point for working from their real ideas about gender-based violence. This means being sensitive enough to take a position without forcing or breaking the dialogue and to know how to set limits through argumentation and not only through imposition. In the search for safe spaces where revictimization was avoided, some of the educational figures expressed the use of non-mixed spaces. In these spaces, the participants could talk about their experiences without fear of being dishonored again, finding similar situations in the group, which allowed them to understand the structural dimension of the problem and to overcome the guilt they often felt as survivors. On the other hand, they mentioned how the non-male mixed spaces allowed them to deconstruct the idea of emotionally unexpressive masculinity, generating new relational dynamics between men; and enabling participants to recognize themselves as people socialized in domination, gradually deconstructing their masculinity. However, despite the benefits mentioned above, we believe that non-mixed groups have the disadvantage of making a too narrow classification, which is not adjusted to reality. This can generate a lot of violence in the case of work with captive audiences when, for example, we assign to the male group a boy who is constantly assaulted in class for having a non-hegemonic masculinity. This is why we recommend this strategy when it is a voluntary activity, believing it advisable to include in the women’s groups those identities that also suffer from sexist violence: trans women, non-binary people, etc.

In short, as we have seen, the analysis of the experiences of these educational figures highlights the value of reformulating the pedagogical relationship as a critical dialogue of knowledge through urban artistic expression. This approach seems to highlight the complexity of creative interaction with their everyday, personal and collective realities, which is why it is important to avoid hasty readings –perhaps due to ageist, classist, racist or heteronormative biases– that ignore the potential of certain aesthetic disruptions to confront the web of oppressions experienced by adolescents, especially gender-based violence. The characterization of these experiences with a thick, unidirectional stroke can abound in the annulment of agency –if not in the revictimization– of those who try to appropriate the word and the denied spaces. If the systemic nature of gender-based violence demands the collective articulation of prevention and transformation (Olufemi, [2020] 2023), taking care of organizational trials such as the ones we have analyzed could already be part of the dismantling of the deep web of violence.

Finally, we would like to mention some of the limitations of this research, which suggest future lines of work: the lack of identification and interviews of more female educational figures who develop their socio-educational work through Rap music; the need to incorporate participant observation in this type of practices in order to triangulate the information obtained; or the necessary collection of the perception of girls and boys before and after going through this type of experiences, in order to approach the impact it may have had on them.

Contributions

|

Contributions |

Authors |

|

Conception and design of the work |

Author 2 |

|

Document search |

Author 1 & Author 2 |

|

Data collection |

Author 2 |

|

Data analysis and critical interpretation |

Author 1 & Author 2 |

|

Version review and approval |

Author 1 & Author 2 |

Funding

The research did not have funding sources.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Bibliographical References

Acosta Faneite, S. F. (2023). Los enfoques de investigación en las Ciencias Sociales. Revista Latinoamericana Ogmios, 3(8), 82-95. https://doi.org/10.53595/rlo.v3.i8.084

Adjapong, E. S., & Emdin, C. (2015). Rethinking pedagogy in urban spaces: Implementing Hip-Hop pedagogy in the urban science classroom. Journal of Urban Learning, Teaching, and Research, 11, 66-77. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1071416

Alemany Arrebola, I., González Gijón, G., Ruiz Garzón, F., & Ortiz Gómez, M. D. M. (2019). La percepción de los adolescentes de las prácticas parentales desde la perspectiva de género. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (33), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI

Álvarez García, D., del Val, F. & Alonso Bustamante, M. (2024). Del beat al reguetón: estudios sobre juventud, subculturas y músicas populares en España. Historia Actual Online, 63 (1), 95-110.

Aubert Simon, A.,Melgar Alcantud, P. & Padrós Cuxart, M. (2010). Modelos de atracción de los y las adolescentes. Contribuciones desde la socialización preventiva de la violencia de género. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 17(10), 73-82. http://hdl.handle.net/10366/118445

Ballarín, M. (2019) Introducción. En M. Ballarín (coord.). Historia de la danza Vol. III, (pp. 8-49). Mahali.

Bas Peña, E., Pérez de Guzmán, V., & Vargas Vergara, M. (2014). Educación y Género. Formación de los educadores y educadoras sociales. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 23, 95-119. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2014.23.05

Bas Peña, E. (2015). Educación social y género. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 23, 13-20. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2014.23.01

Baxter, V. K., & Marina, P. (2008). Cultural meaning and Hip-Hop fashion in the African-American male youth subculture of New Orleans. Journal of Youth studies, 11(2), 93-113.

Belausteguigoitia Rius, M. (coord.) (2022). Género: rabia, ritmo, ruido, risa y responsabilidad. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de Género

Butler, J. (2021). La fuerza de la no violencia. Paidós.

Casu, M. (2024). Madrid desde el baile. CentroCentro.

Chicharro Merayo, M. D. M. (2003). La perspectiva cualitativa en la investigación social: la entrevista en profundidad. Enlaces: revista del CES Felipe II, (8), 1-7. http://bit.ly/3ToEq8D

Cipollone, M. D. (2022). Atlas. ti como recurso metodológico en investigación educativa. Anuario digital de investigación educativa, (5), 122-133. https://revistas.bibdigital.uccor.edu.ar/index.php/adiv/article/view/5280

Cunningham, M., & Rious, J. B. (2015). Listening to the voices of young people: Implications for working in diverse communities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), 86-92.

Davis, A. ([1981] 2004). Mujer, raza y clase [Women, Roce & Class]. Ediciones Akal.

Díaz Bazo, C. (2019). Las estrategias para asegurar la calidad de la investigación cualitativa. El caso de los artículos publicados en revistas de educación. Revista Lusófona de educação, 44, 29-45. https://doi.org/10.24140/issn.1645-7250.rle44.02

Fernández Martorell, C. (2020). Observaciones a la retórica de las nuevas propuestas pedagógicas. En C. Fernández et al., Pedagogías y emancipación (99-127). ARCADIA & MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Garcés, M. (2020). Escuela de aprendices. Galaxia Gutenberg.

Garcés-Montoya, Á. G. & Acosta-Valencia, G. L. (2023). Educación social en movimientos juveniles de arte urbano. Escuelas de rap en Medellín. Revista Colombiana de Educación, (87), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.17227/rce.num87-12740

González Barea, E. M., & Rodríguez Marín, Y. (2020). Estereotipos de género en la infancia. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (36), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2020.36.08

Graham, J. (2020). Técnicas para vivir de otra manera. Nombrar. Componer e instituir de otra manera. En C. Fernández et al., Pedagogías y emancipación (49-76). ARCADIA & MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Hall, S. & Jefferson, T. ([1993] 2014). Rituales de resistencia. Subculturas juveniles en la Gran Bretaña de postguerra. Traficantes de Sueños.

Haaken, J., Wallin-Ruschman, J., & Patange, S. (2012). Global hip-hop identities: Black youth, psychoanalytic action research, and the Moving to the Beat project. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 22(1), 63-74.

Hill Collins, P. & Bilge, S. ([2016] 2019). Interseccionalidad [Intersectionality]. Ediciones Morata

hooks, b. ([1994] 2021). Enseñar a transgredir. La educación como práctica de libertad. Capitán Swing.

Hormigos-Ruiz, J., Gómez-Escarda, M., & Perelló-Oliver, S. (2018). Música y violencia de género en España. Estudio comparado por estilos musicales. Convergencia, 25(76), 75-98. https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v25i76.4291

Hunt, A. N. (2018). “Trappin’Ain’t Shit to Me”: How Undergraduate Students Construct Meaning Around Race, Gender, and Sexuality within Hip-Hop. Gender and the Media: Women’s Places, 26, 69-85. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-212620180000026006

Izquierdo-Montero, A. & Aguado-Odina, T. (2020). Discursos de odio: una investigación para hablar de ello en centros educativos. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 24(3), 175-195. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v24i3.15385

Jacobson, G. (2015). Racial Formation Theory and Systemic Racism in Hip-Hop Fans’ Perceptions. Sociological Forum, 30 (3), 832-851.

Johnson, K., Markham, C., & Tortolero, S. R. (2017). Thematic Analysis of Mainstream Rap Music-Considerations for Culturally Responsive Sexual Consent Education in High School. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 8(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.58464/2155-5834.1328

Kim, J., & Pulido, I. (2015). Examining Hip-Hop as culturally relevant pedagogy. Journal of curriculum and pedagogy, 12(1), 17-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2015.1008077

Ladrero, V. (2016). Músicas contra el poder. Canción popular y política en el siglo XX. La Oveja Roja.

Loayza Maturrano, E. F. (2020). La investigación cualitativa en Ciencias Humanas y Educación. Criterios para elaborar artículos científicos. Educare Et Comunicare. Revista de investigación de la Facultad de Humanidades, 8(2), 56-66. https://doi.org/10.35383/educare.v8i2.536

López Cuenca, A., Rodríguez Medina, L., & Ismael Simental, E. (2021). Prácticas culturales colaborativas y sociabilidad débil. Una caracterización a partir de experiencias autogestivas en Tijuana y Monterrey, México. Arte y Políticas de Identidad, 25(25), 52-72. https://doi.org/10.6018/reapi.506201

Marchant, O. (2024). Estética conflictual. Ned ediciones.

Morentin Encina, J., Izquierdo Montero, A. & Ballesteros Velázquez, B. (2022). Análisis temático de contenido. Notas y orientaciones para un mapa de ruta. En M.F. González y B. Ballesteros (Coords.). Comprender el mundo para (intentar) transformarlo. Una guía posible para el análisis cualitativo de datos (pp. 113-156). UNED.

Muhammad, K. R. (2015). Everyday people: public identities in contemporary Hip-Hop culture. Social Identities, 21(5), 425-443.

Mustaffa, J. B. (2022). Racial Justice Beyond Credentials: The Radical Politic of a Black College Dropout. The Urban Review, 54(2), 318-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-021-00612-3

Olufemi, L. ([2020] 2023). Feminismo interrumpido. Reventar el poder. Rayo Verde.

Pégram, S. (2015). Un peu de respect for the ladies: Female Rappers and Hip-Hop Educational Philosophy in France. Liberal Arts, 19(2), 57-83.

Sánchez Gómez, M. C., Palacios Vicario, B., & Martín García, A. (2015). Indicadores de violencia de género en las relaciones amorosas. Estudio de caso en adolescentes chilenos. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 26, 85-109. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2015.26.04

Tracy, S. (2021). Calidad cualitativa: ocho pilares para una investigación cualitativa de calidad. Márgenes Revista De Educación De La Universidad De Málaga, 2(2), 173-201. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v2i2.12937

Ugena-Sancho, S. (2023). Violencia de género. En L. Alegre, E. Pérez y N. Sánchez (Ed.). Enciclopedia crítica del género. Una cartografía contemporánea de los principales saberes y debates de los estudios de género (487-495). Arpa & Alfil.

Vito, C. (2019). The Values of Independent Hip-Hop in the Post-Golden Era. Springer Nature.

HOW TO CITE THE ARTICLE

|

Burón-Vidal, M. A. y Laforgue-Bullido, N. (2025). Expresiones artísticas urbanas para el trabajo socioeducativo de las violencias de género. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 47, 189-202. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2025.47.11 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

Miguel Ángel Burón Vidal. Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación I, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Calle Juan del Rosal, 14 Moncloa. Segunda Planta, despacho 2.14. E-mail: ma.buron@edu.uned.es Noemi Laforgue Bullido. Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación II, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Calle Juan del Rosal, 14 Moncloa. Segunda Planta, despacho 2.14. E-mail: nlaforgue@edu.uned.es |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

MIGUEL ÁNGEL BURÓN VIDAL https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5721-4614 Investigador docente en formación en la Escuela Internacional de Doctorado de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Programa de Doctorado en Educación. Diplomado en Magisterio por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid – ESCUNI. Realizó el máster Euro-Latinoamericano en Educación Intercultural de la UNED. Su campo de investigación se enfoca en el acompañamiento educativo de expresiones artísticas urbanas, el potencial cuestionador de las estéticas conflictuales y la facilitación de procesos colectivos transformadores. NOEMI LAFORGUE BULLIDO https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3690-6077 Doctora en educación. Personal docente e investigador en formación de la Facultad de educación de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED). Licenciada en Pedagogía por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Realizó el máster Intervención Psicosocial y Comunitaria de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Su campo de investigación se centra en el trabajo con adolescencias a través de la música Rap y otras expresiones artísticas, la detección y prevención de los discursos de odio y la transformación de los espacios educativos para la equidad y la justicia social. |

Notes

1 Also Known As”, referring to the artistic name of the rappers.

2 These are groups in which only people who share an identity characteristic can participate (for example, groups formed by people who share the identity “woman”). One of the objectives of these groups is to create safe spaces to talk about the violence experienced as a result of sharing that identity trait in order to generate common strategies in this regard.