eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2024.46.12

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

Versión en español: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/article/view/105041/81396

Social networks and linkages: a systematic literature review (PRISMA) on the impact of social capital in youth communities

Redes sociales y vínculos: revisión sistemática (PRISMA) sobre el impacto

del capital social en comunidades de jóvenes

Redes sociais e laços: revisão sistemática da literatura (PRISMA) sobre o impacto

do capital social nas comunidades juvenis

Laia ALGUACIL MIR  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5562-5093

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5562-5093

Paloma VALDIVIA VIZARRETA  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1499-5478

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1499-5478

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Received date: 01.III.2024

Reviewed date: 04.V.2024

Accepted date: 04.XI.2024

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Paloma Valdivia Vizarreta: Departamento de Teorías de la Educación y Pedagogía Social, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Edificio G6-Despacho 171. Campus de Bellaterra, c.p. 08193, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona. E-mail: paloma.valdivia@uab.cat

|

KEYWORDS: Social capital; youth; social networks; online communities; linkages. |

ABSTRACT: In today’s digital society, social networks have acquired great importance in the lives of young people, who use them as virtual spaces to establish and maintain social relationships. The aim of this systematic literature review is to analyze the potential of use of social networks to contribute to the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people. Following the indications of the PRISMA 2020 statement, 18 relevant studies that met the established inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified and selected. The results indicate that social networks play a significant role in the development of social capital in virtual youth communities. These platforms provide opportunities for social interaction, identity building and community participation, thus strengthening social connections, strengthening young people’s sense of belonging and empowering them. |

|

PALABRAS CLAVE: Capital social; jóvenes; redes sociales; comunidades virtuales; vínculos. |

RESUMEN: En la sociedad digital actual, las redes sociales han adquirido una gran importancia en la vida de los jóvenes, quienes las utilizan como espacios virtuales para establecer y mantener relaciones sociales. El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática de la literatura es analizar el potencial del uso de las redes sociales para contribuir al desarrollo del capital social en las comunidades virtuales de jóvenes. Siguiendo las indicaciones de la declaración PRISMA 2020, se identificaron y seleccionaron 18 estudios relevantes que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión y exclusión establecidos. Los resultados indican que las redes sociales juegan un papel significativo en el desarrollo del capital social en las comunidades virtuales de jóvenes. Estas plataformas brindan oportunidades para la interacción social, la construcción de la identidad y la participación comunitaria, fortaleciendo así las conexiones sociales, fortaleciendo el sentido de pertenencia de los jóvenes y empoderándolos. |

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Capital social; juventude; redes sociais; comunidades online; ligações. |

RESUMO: Na sociedade digital atual, as redes sociais adquiriram uma grande importância na vida dos jovens, que as utilizam como virtuais para estabelecer e manter relações sociais. O objetivo desta revisão sistemática da literatura é analisar o potencial da utilização das redes sociais para contribuir para o desenvolvimento do capital social em comunidades virtuais de jovens. Seguindo as indicações da declaração PRISMA 2020, foram identificados e selecionados 18 estudos relevantes que cumpriam os critérios de inclusão e exclusão estabelecidos. Os resultados indicam que as redes sociais desempenham um papel significativo no desenvolvimento do capital social nas comunidades virtuais juvenis. Estas plataformas proporcionam oportunidades de interação social, construção de identidade e participação comunitária, fortalecendo assim as ligações sociais, fortalecendo o sentimento de pertença dos jovens e capacitando-os. |

1. Introduction

Currently, 84 % of people between the ages of 18 and 29 use at least one social network (Wong, 2023). These social network (SN) platforms have created a virtual space where people can connect with others regardless of geographic distance and cultural barriers. The transition from a static phase of the 1990s, interactive platforms and social networks in the 2000s, led us to a shift to collaborative platforms in the 2020s where these social networks actively engage users in the creation and dissemination of online content. This has had a significant impact on youth communities, the main drivers and users of these networks (Vromen et al., 2015, cited in Bano et al. 2019).

Despite being a highly widespread concept, there is no single or commonly accepted definition of social networks. In the beginning, Kaplan & Haenlein (2010), cited in Tulibaleka & Katunze (2023), defined social networks as “a group of Internet-based applications that are based on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and sharing of user-generated content” (p. 2). Likewise, for Way & Malvini Redden (2017), cited in Brough et al. (2020), social networks are significant environments where young people form identities, create and maintain relationships; spaces where young people understand their cultivated identities and experiences in these social networks, which take place in different virtual communities. These interactions vary according to the environment in which they take place and influence the dynamics that are generated and how social capital is built. For Matenda et al. (2020), the interactive capacity of social networks allows young people to collaborate, coordinate and generate social capital (SC) in virtual communities, in the same way that the interrelation or coexistence with face-to-face groups or the absence of these, all these actions influence the way in which these relationships develop in the virtual environment. In addition, it should be noted that a social media platform also has limitations depending on its design and structure. In this way, the social relations that occur adjust to the “architecture” of the SN, although the use given to them depends on the members that make up the community (Ramos-Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023).

The widespread use of social networks in much of the world has influenced the commitment of young people to their civic participation, in the broadest sense of the concept. Social networks have become one of the main sources of information and communication (understood in a bidirectional sense, no longer just unidirectional by the media towards users) for the general population, and especially for young people (Newman et al., 2019). Currently we know that social networks promote greater commitment among young people because they form virtual communities. However, it is not clear what happens and what conditions promote it. This is a relevant question, since community participation is what enables young people to contribute significantly to the development of current societies (Matenda et al., 2020), as well as the identification of the participant groups. Consequently, the interest of many countries in including in their youth agendas policies aimed at increasing the community participation of young people through social capital and youth empowerment is evident. A relevant example would be the “Integration of young adults with fewer opportunities in organizations and reinforce their empowerment” project (Valdivia et al., 2022).

Currently, it is not possible to answer this question ignoring the virtual communities that are formed in SN. Virtual communities are defined as “the organization of Internet users who share similar interests, tastes, preferences and points of view, who meet in virtual space to share information, work or communicate with their peers” (Loaiza-Ruiz, 2018, p. 223, in Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023, p. 3), also influenced by the degree of formality and the shared expectations of the people who form these communities. Although the digital component is what characterizes these communities, members can also form a community outside the virtual plane. For example, a class group from a secondary education institute can have its virtual community on a SN.

As presented previously, there is evidence in the scientific literature that interactions between young people in these virtual communities contribute to the development of SC. According to Bourdieu (1985), cited in Matenda et al. (2020), social capital refers to how a person’s social connections can be used to access resources that are important to their well-being. For Martínez & Úcar (2022), it is generated from the structure of social relationships that exist in a community and the connection of the individuals that are part of it. Martínez & Úcar (op.cit.), referring to Putnam (1993), Durnston (1999) and Atria et al. (2003), highlight the collective nature of SC as a quality of groups, communities and institutions. Likewise, they defend that SC is not only a resource of individuals and communities, but that it is a collective and community capacity. In this way, communities can increase and develop it. There are five key factors in the SC of communities: (1) trust, (2) norms, (3) relationships, (4) values and (5) participation, voluntariness and access to information (Martínez & Úcar, op.cit).

Formal and informal social networks are essential components of young people’s SC, among others due to the links they form with other members of the community. According to Woolcock and Narayan (2000), there are different types of relationships depending on their nature: bonding, bridging and linking. Firstly, bonding relationships are socially close and are generated from points of agreement inherited or created as a result of frequent personal contact. On the other hand, bridging relationships are characterized by being horizontal and semi-closed. These are moderately close ties based on acquired points of agreement. These types of relationships can become bonding relationships. Finally, linking relationships are characterized by being asymmetrical and mostly vertical, as they occur between individuals with different spaces of power. All these types of links are essential for the SC development of young people today.

Generally, there is evidence that SNs have become a powerful source of SC development, as they have facilitated the mobilization of resources and the maintenance and creation of relationships. However, more research is required to understand how this development of SC occurs in SN. For this reason, the research question of this systematic review of the literature is posed: how can social networks contribute to the development of SC in virtual communities of young people? To give a more concrete answer, three research sub-questions have been raised: How do social networks contribute to the development of social capital in youth communities? What types of social capital have been generated from the use of social networks in virtual youth communities? What are the functionalities of social network platforms that facilitate the development of social capital?

By better understanding how social media can promote the development of SC among youth, more effective interventions and policies can be designed to harness the potential of these platforms for the benefit of youth communities. Furthermore, it is hoped that this research will prompt reflection on the wider effects and implications of social media in today’s society, and how we can encourage responsible and constructive use of these digital tools.

2. Objectives

The general objective of this research is to analyze the potential of using social networks to contribute to the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people. Likewise, three specific objectives have been specified:

– To describe the general characteristics of the experiences of developing social capital through social networks in virtual communities of young people.

– To identify how social capital is developed as a result of the use of social networks in virtual communities of young people.

– To analyze the functionalities of social media platforms that promote the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people.

3. Methodology

A systematic literature review has been done to answer the questions and achieve the objectives of the research, since this methodology allows us to answer the questions posed using a rigorous method. Guirao Goris (2015) defines a systematic review as a summary of evidence on a given topic, which is obtained through a rigorous search and analysis process to minimize biases. Specifically, it is an exploratory systematic review, in that it seeks to analyze and synthesize the existing knowledge in scientific literature (Codina, 2021).

Following this type of methodology, the aim is to identify, evaluate and synthesize existing studies to answer a specific question and draw conclusions from data already collected. In order to guarantee the transparency and veracity of the results, the indications of the PRISMA 2020 declaration have been followed throughout the process (Page et al., 2021). The SALSA framework has been used as a reference to ensure that the research is rigorous, organizing it into 4 phases: search, evaluation, analysis and synthesis.

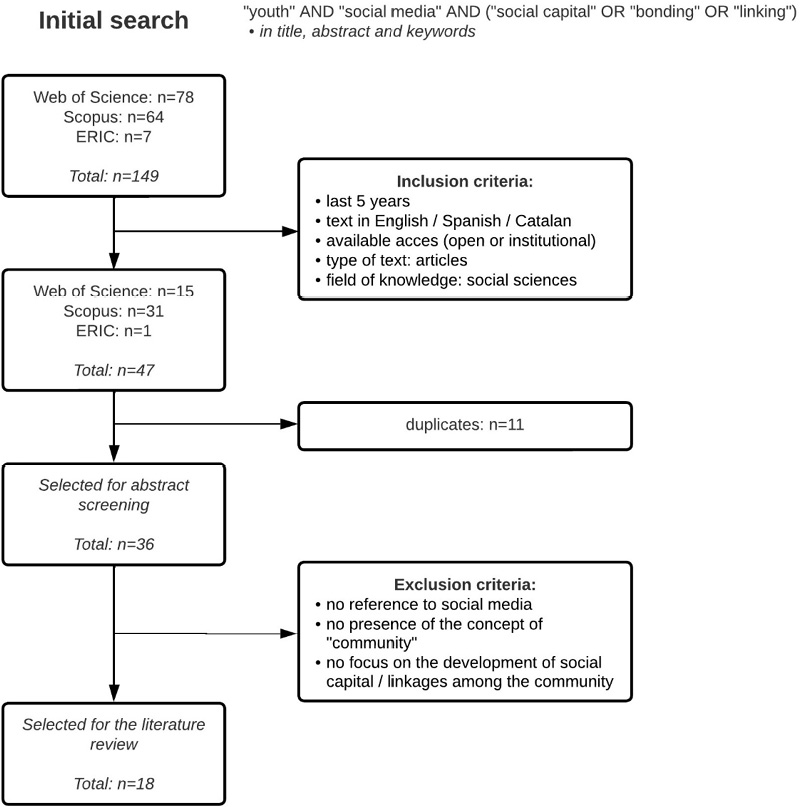

First of all, the systematic search was conducted (Figure 1). Considering the research question, we worked with three main themes: (1) young people, (2) social networks and (3) social capital. The final search expression resulted in: “youth” AND “social media” AND (“social capital” OR “bonding” OR “linking”), which was applied in the title, summary and keywords fields. The search was conducted in English to cover international literature. Three search engines (Scopus, Web of Science and ERIC) were used because of their relevance to educational and social science research. These databases were selected for their rigor and breadth of coverage:

1. Scopus, one of the largest multidisciplinary databases, offers global access to peer-reviewed studies, including social sciences and technology, essential for the analysis of social networks and social capital.

2. Web of Science is recognized for its high quality and coverage in the social sciences, which allows tracking citations and key studies that influence the field.

3. ERIC was chosen for its focus on educational research, providing access to specific studies on youth, social networks and social capital development in educational contexts.

The combination of these databases ensures comprehensive and adequate coverage for the objectives of this exploratory review. After reviewing the results, it was not necessary to adjust the keywords.

It should be noted that a search was carried out on the youth collective in general, without specifying any element of their context, since the objective was to obtain a general overview of all the areas in which all types of young people use SNs to form communities that contribute to developing SC. However, from an early stage of the search it was identified that the majority of the results referred to groups of young people in vulnerable situations. This may be due to the fact that the concept of SC has traditionally been linked to community development studies, which are usually carried out in this type of communities. Likewise, it is also worth noting that the selection of the three search engines creates a bias in the results that is, to a certain extent, intentional. These are databases that mainly contain publications from Anglo-Saxon journals and, although authors from other countries can publish in these journals, it is true that the data can be geographically biased. However, this is appropriate for the purpose of this review, since it is necessary to study contexts where young people use NS regularly. However, we acknowledge that this is not the reality of all young people in all countries.

Initially, n = 149 results were obtained (Web of Science n = 78, Scopus n = 64 and ERIC n = 7). Next, the results were evaluated according to the inclusion criteria:

– last 5 years (2019-2023)

– text in English / Spanish / Catalan

– available access with university permissions

– text type: articles

– field of knowledge: social sciences

The application of criteria reduced the results to n = 47 (Web of Science n = 15, Scopus n = 31 and ERIC n = 1). After removing duplicates, n = 36 remained. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, and the following exclusion criteria were applied, which eliminated n = 18 documents:

– no mention of social networks

– no concept of community

– no focus on developing social capital/connections in the community

This process reduced the sample to n = 18 documents for this systematic review.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the systematic search process. Source: Own elaboration.

The resulting documents are summarized in Table 1.:

|

Table 1. Summary of documents selected for the systematic review |

||

|

Reference |

Context |

Method |

|

Kornbluh (2019) |

United States |

Mixed method sequential: – Questionnaire – Social network design (3 waves) – Semi-structured interviews |

|

Matenda et al. (2020) |

South Africa |

Mixed method sequential: – Quantitative questionnaire – Focus groups |

|

Brough et al. (2020) |

United States |

Qualitative study: interviews |

|

Yuen y Tang (2021) |

Hong Kong |

Mixed method: – Public quantitative data from Instagram – Semi-structured interviews |

|

Bano et al. (2019) |

Pakistan |

Quantitative study: questionnaire |

|

Kasperski y Blau (2023) |

Israel |

Qualitative study: grounded theory – Semi-structured interviews – Observation of online student-teacher interactions |

|

Brown et al. (2022) |

United States |

Qualitative study: interviews |

|

Tisdall y Cuevas-Parra (2022) |

Not specified |

Theoretical article (essay), references existing literature |

|

Junus et al. (2023) |

Hong Kong |

Quantitative study: questionnaire applied in 2 waves |

|

Nursey-Bray et al. (2022) |

Australia |

Mixed method: – Document analysis – Semi-structured interviews – Questionnaire |

|

Dredge y Schreurs (2020) |

Belgium |

Systematic literature review |

|

Walby y Gumieny (2020) |

Canada |

Qualitative study: document analysis (content from Twitter accounts) |

|

Tulibaleka y Katunze (2023) |

Uganda |

Qualitative study: – Semi-structured interviews – Focus groups |

|

Ramos Mancilla y Flores-Fuentes (2023) |

Mexico |

Qualitative study: – Participant observation – Observation of communities in digital environments |

|

Theben et al. (2021) |

Spain |

Qualitative study: literature review and analysis of an inventory of good practices in European countries. To collect information on good practices: – Document analysis – Qualitative questionnaire – Interviews |

|

Chan et al. (2021) |

China, Taiwan and Hong Kong |

Quantitative study: questionnaire |

|

Newman (2019) |

Not specified |

Theoretical article (essay), references existing literature |

|

Gureeva et al. (2022) |

United States |

Mixed method: – Questionnaire – Social network analysis – Semi-structured interviews |

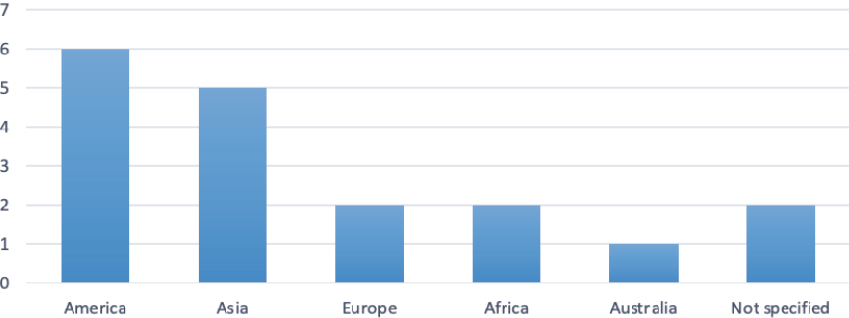

Figure 2 shows a graph that summarizes the graphic distribution of the documents reviewed by continents. The most frequent are America (n = 6) and Asia (n = 5). Articles classified as “non-contextualized” are those theoretical articles that, therefore, do not report concrete experiences in a specific context.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of the reviewed studies. Source: Own elaboration.

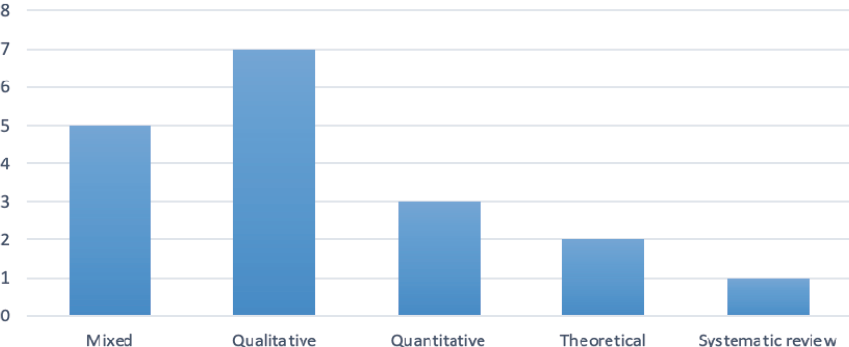

Figure 3 shows a graph that summarizes the types of studies reviewed according to their methodological design. The most frequent are qualitative (n = 7) and mixed (n = 5).

Figure 3. Type of reviewed study according to methodology. Source: Own elaboration.

After the evaluation process, the documents were analyzed to extract relevant data. To this end, the documents were read, and their content was analyzed by means of an analysis sheet, prepared in accordance with the research subquestions and the objectives of this systematic review. Subsequently, the team proceeded to the phase of synthesis of the analyzed content. A table was used to organize these results and proceed to their discussion, which is presented in the following section.

4. Results

In order to answer the objective and question of this research (how can social networks contribute to the development of social capital in youth communities?), the results are presented based on the research questions:

– What are the analyzed experiences of social capital development through social networks like?

– What evidence is there about the development of social capital? What functionalities of social media platforms facilitate the development of social capital?

4.1. How do social networks contribute to the development of social capital in youth communities?

Of the documents reviewed, first the general characteristics of the experiences they report have been identified. This has been possible for 15 documents, since the systematic review and the two theoretical articles have been excluded, since they do not report results on a specific experience that can be described. The experiences reported are varied in their nature. In order to provide an overview of these experiences, they have been categorized in Table 2 using the following study variables:

– Ambit. It refers to the social and study area where the experience has been developed. This variable is crucial because it allows us to understand in which specific contexts (such as education, community, activism, welfare, among others) the interactions that potentially develop social capital are generated. Different environments present different dynamics and needs in terms of the use of social networks. The analyzed experiences cover a wide variety of settings, reflecting the diversity of contexts in which interactions that contribute to the development of youth social capital are generated. Studies in domains of community development (Matenda et al., 2020; Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023) and social activism (Yuen & Tang, 2021; Chan et al., 2021) predominate, while other experiences focus on psychological well-being (Bano et al., 2019; Junus et al., 2023), education (Kornbluh, 2019; Kaspersky & Blau, 2023), and community volunteering (Nursey-Bray et al., 2022). This suggests that social networks have the potential to contribute to youth social capital in very diverse contexts, facilitating both community empowerment and psychological support and access to educational opportunities (Soler et al. 2017).

– Participating group. It refers to the type of young people who have participated in the experience, focusing on what unites them as a community. Identifying the type of youth who have participated (e.g., high school students, university students, vulnerable youth) is critical, as the demographic and social characteristics of the participants can influence how social capital networks are formed and strengthened. This analysis makes it possible to determine whether certain groups have an easier time generating social capital through social networks than others. Most studies focus on high school and college students (Kornbluh, 2019; Matenda et al., 2020; Brough et al., 2020), while some studies include specific groups such as vulnerable youth (Brough et al., 2020). The diversity in the participating groups indicates that social networks are not only useful for generating social capital in homogeneous communities or with a very specific profile, but that they are present in very disparate contexts.

– Coexistence of an in-person group. In the event that the virtual community is the digitalization of a group that previously existed only in person, it has been categorized as “yes”; If the group only exists in the virtual plane, it has been categorized as “no”. The prior existence of a face-to-face group may influence the quality and intensity of social relationships within the virtual community, affecting the formation of social capital. In some cases, virtual communities represented a continuation of pre-existing face-to-face groups, such as class groups in educational experiences (Kornbluh, 2019; Kaspersky & Blau, 2023), or community groups (Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023). In these cases, the existence of a previous face-to-face community seems to favor greater social cohesion in the digital environment. However, in most of the studies, the youth communities were exclusively virtual, which could suggest that social networks are also capable of facilitating the creation of new forms of social capital, without the need for a prior face-to-face relationship.

– Network formality. It refers to the degree of formality of the experience, with socio-educational interventions being formal that involve the creation of a virtual community in NS with a specific purpose by the adult responsible for the intervention. On the other hand, informal experiences are those in which virtual communities have formed in a completely natural way. The semi-formal ones are those in which the initiative to create the virtual community has been that of the young people themselves, so it is formalized and used but without a specific purpose on the part of the adult. The results show how SNs can be used in both types of contexts; however, their informal use stands out. In fact, in most of the experiences, SNs emerge informally, without a structured purpose, reflecting their potential to facilitate spontaneous interactions among young people, which contribute to the development of social capital.

– Adult dynamization. This variable refers to the presence of adults who facilitate or guide the virtual community. The participation of an adult facilitator can be crucial in formal or semi-formal communities, where a specific development of social capital is sought. Adults can play key roles in moderation, goal setting and conflict resolution within the community. This is the case of the teacher-student relationship in the study by Kaspersky & Blau (2023) or in socio-educational interventions in third sector entities (Theben et al., 2021). However, in many informal experiences, adult participation was not observed, suggesting that young people can also manage their own communities autonomously in virtual environments.

– Associated training. This variable considers whether any complementary training is offered to participants to facilitate the development of social capital in virtual communities that are conducted at a formal or semi-formal level. Some formal experiences included supplemental training for participants, such as leadership skills (Kornbluh, 2019) or digital competencies (Theben et al., 2021). Training can provide youth with the tools needed to interact more effectively in the virtual community, thus increasing the likelihood of generating social capital. However, most experiences, being informal, do not include specific training. This may reflect less structured planning in this type of network, although it is not a determinant for the development or non-development of social capital in youth virtual communities.

|

Table 2. Descriptive summary of experiences in the development of social capital through social networks |

||||||

|

Experience |

Ambit |

Participating group |

Coexistence of an in-person group |

Network formality |

Adult dynamization |

Associated training |

|

Kornbluh (2019) |

Sociopolitical development and participation to improve the community |

Secondary education students |

Yes (class group) |

Formal (part of a school project integrated into teaching hours) |

Not specified |

Yes (on leadership skills) |

|

Matenda et al. (2020) |

Community development |

Secondary education and university students |

Some, but not necessarily |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Brough et al. (2020) |

Development of communities in vulnerable situations / minorities |

Minority university students |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Yuen & Tang (2021) |

Youth social activism |

University students |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Bano et al. (2019) |

Psychological wellbeing |

University students |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Kasperski & Blau (2023) |

Teacher-student relationship |

Secondary education students |

Yes (class group) |

Semi-formal (students’ own initiative) |

Yes (teachers) |

No |

|

Brown et al. (2022) |

Access to post-obligatory studies |

Secondary education students |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Tisdall & Cuevas-Parra (2022) |

Youth social activism |

Not applicable because it is a theoretical article |

||||

|

Junus et al. (2023) |

Psychological wellbeing |

Young people with a history of psychological disorder |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Nursey-Bray et al. (2022) |

Community volunteering |

Youth community members |

No |

Informal |

Yes (organization that leads volunteering) |

No |

|

Dredge & Schreurs (2020) |

Daily use of SNs for young people |

Not applicable because it is a systematic review |

||||

|

Walby & Gumieny (2020) |

Community development local police initiative |

Youth community members |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Tulibaleka & Katunze (2023) |

Transition of youth from rural to urban areas |

Young people from rural areas |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes (2023) |

Informal learning for community development |

Youth from indigenous communities |

Yes (community itself) |

Formal (researchers’ intervention) |

1 group yes; 1 group no |

1 group yes; 1 group no |

|

Theben et al. (2021) |

Socio-educational interventions in third sector entities |

Young people associated to these entities |

Yes (group at the entity) |

Formal (socio-educational interventions of the entity) |

Yes (educators) |

Yes (on digital competence) |

|

Chan et al. (2021) |

Youth social activism |

University students |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

|

Newman (2019) |

Socio-educational interventions in third sector entities |

Not applicable because it is a theoretical article |

||||

|

Gureeva et al. (2022) |

Youth social activism |

Not specified |

No |

Informal |

No |

No |

As can be seen in Table 2, the ambits of experiences are diverse. This can be explained by the versatility of use of SN, as well as the diversity of spaces and situations in which the development of SC can be evidenced, both by individuals and communities. However, despite the variety, certain coincidences are identified. Some experiences refer to community development in general (Kornbluh, 2019; Brough et al., 2020; Walby & Gumieny, 2020; Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023), to youth social activism (Yuen & Tang, 2021; Tisdall & Cuevas-Parra, 2022; Chan et al., 2021; Gureeva et al., 2022), to transition stages that characterize the life stage of young people where they must make many decisions (Brown et al., 2022; Tulibaleka & Katunze, 2023) and the links between community members (Kasperski & Blau, 2023; Nursey-Bray et al., 2022), among others.

Regarding the participating group, 8 of the 18 studies refer to high school or university students. This can be explained by the researchers’ accessibility to the sample. However, the common element between all groups is that they are young people who are part of physical communities, but virtual communities.

On the other hand, for the category’s coexistence of in-person group, network formality, adult dynamization and associated training, the frequencies of each subcategory have been calculated and the corresponding percentages have been calculated in Table 3. The most frequent is that there is no in-person group equivalent to the virtual community; that they are informal experiences; that they are not dynamized; and that do not have associated training. The details in Table 2 help understand the association between these options.

|

Table 3. Calculation of frequencies of descriptive categories of the reviewed studies |

|||

|

Coexistence of an in-person group |

Yes |

4 |

27% |

|

No |

11 |

73% |

|

|

Network formality |

Formal |

3 |

20% |

|

Semi-formal |

1 |

7% |

|

|

Informal |

11 |

73% |

|

|

Adult dynamization |

Yes |

3 |

20% |

|

No |

11 |

73% |

|

|

Not specified |

1 |

7% |

|

|

Associated training |

Yes |

3 |

20% |

|

No |

12 |

80% |

|

The results are the following:

– Coexistence of an in-person group: Most of the virtual communities (73 %) do not have a previous face-to-face group, indicating that these networks are usually formed directly in the digital environment, without relying on previous face-to-face interactions.

– Network formality: 73 % of the communities analyzed are informal, forming spontaneously without a predefined structure. This predominance of informality suggests that young people tend to organize themselves in digital spaces with flexibility and autonomy.

– Adult dynamization: In 73 % of the experiences, the communities operated without adult intervention, which shows that young people manage their online interactions autonomously. Only in 20 % of the cases was there adult facilitation.

– Associated training: 80 % of the experiences did not include complementary training, suggesting that social capital in these communities is developed intuitively or through direct experience, without relying on formal educational interventions.

4.2. What types of social capital have been generated from the use of social networks in virtual communities of young people? What are the functionalities of social networking platforms that facilitate the development of social capital?

As can be seen in the previous question, the documents reviewed present diverse experiences of SN use in virtual communities of young people. However, all the papers have a common element: the results report evidence of SC development when there is participation and involvement in these networks. Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes (2023) are the only authors who, in one of the two virtual communities of their socio-educational intervention, do not report SC development. The authors explain this because of the functionalities of the SN platform chosen (Google+, a topic that will be developed in greater depth in the following section), as well as the lack of perceived usefulness of using this SN to form a community on the part of the young people.

In the rest of the cases, young people actively participate in virtual communities with a clear purpose, which is closely related to the field of experience. For example, in the experience of Tulibaleka & Katunze (2023) young people in rural areas use SNs to receive support in the process of transition to the big city and cover all the needs that arise. In Kornbluh’s (2019) experience, young people use SNs to make their community improvement project known to other institutes, as well as to be informed of their projects and establish alliances with young people in the territory who they do not know because they attend different high schools. In this way, it is observed that the sense of the network is a common element for the participation of young people and for the development of SC. The degree of formality of the network, the coexistence of in-person groups, adult dynamization or associated training do not seem to be determining elements.

4.2.1. Types of generated social capital

Considering the diversity of experiences, Woolcock and Narayan’s (2000) classification of types of bonding, bridging and linking has been used to report SC developments, since it is a widely used and accepted classification in the field of social capital studies.

Bonding ties

Bonding ties refer to socially close relationships that are generated from points of coincidence inherited or created as a result of frequent personal contact. SNs enable the development of bonding ties in that they strengthen already existing relationships, especially in the case of face-to-face group coexistence. For example, Kasperski & Blau (2023) explain that the creation of a Facebook group with all members of the class allowed them to improve the quality of relationships and increase the feeling of trust and relevance to the group. This was possible because the SN allowed them to get to know other more personal dimensions of the lives of classmates and teachers, which allowed them to discover common interests, discover new sensitivities, have greater understanding, etc. This also happens with other platforms such as WhatsApp, for which Bano et al. (2019) identified a significant positive association between its use and SC bonding.

Similarly, Matenda et al. (2020) reported the usefulness of SNs to foster cohesion and contact with trusted peers when they need support during university, thanks to the iterative communication, trust, and intimacy that these platforms offer. Junus et al. (2023) identifies similar results in peer support for mental health. Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes (2023) report that indigenous young people who were part of the virtual community on Facebook strengthened the relationships they already had and further developed community identity by sharing publications related to memory, daily activities, parties and celebrations, landscapes (of the territory) and claims (also linked to the territory). Finally, related to activism, Yuen & Tang (2021) explain that SNs allowed young people who knew each other but did not have a close relationship to create collegiate ties and intercollegiate communities that facilitated student mobilization during the protest.

In some of these cases, it is made explicit that SNs have given rise to bonding ties because they allow existing relationships to be prolonged in space-time. For example, in the case of Kasperski & Blau (2023) and Matenda et al. (2020), it is reported that young people used SNs to continue providing support outside the classroom. In the case of Tulibaleka & Katunze (2023), young people in rural areas used SNs to stay in touch with their families when they migrated to the city.

In this case, SNs served to enhance the relationships that already existed. Despite being less frequent, evidence has also been identified that SNs can generate new bonding ties that initially begin as bridging. That is, SNs can increase the number of close ties. This is especially relevant for some minorities who connect deeply with people they identify with. In this sense, Brough et al. (2020) identify that SNs allow the formation of communities and networks based on identity. For example, a young person reports having used the hashtag #blackLBGTQ to find friends like him, and another young person reports having connected with local Latina women and mutually supporting her Latino businesses through dedicated Instagram accounts. It is also relevant for people who arrive new to an institution such as the university (Matenda et al., 2020), for people who are shy or have difficulties establishing new face-to-face relationships within a group (Kasperski & Blau, 2023), or for close ties between young people in third sector entities (Newman, 2019).

Bridging ties

Bridging ties refer to horizontal and semi-closed social relationships, moderately close ties based on acquired points of agreement. This type of link is the most frequent that SNs generate, as they allow young people to connect with users or other realities but with certain points of coincidence, and that will not necessarily develop into close relationships such as bonding. Although bonding relationships are more frequent in virtual communities with their equivalent in-person group, bridging relationships are more frequent when there is no in-person group.

In this sense, the use of SNs allows young people to connect with other people’s realities. To achieve this, open social media sites, such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, are more common than closed ones such as WhatsApp or private Facebook groups. For example, Bano et al. (2019) identify a greater association between the use of WhatsApp and bonding than with bridging. For Gureeva et al. (2022), these networks allow citizens to interact with all types of people and learn about various problems, which ultimately influences them and leads them to action. Likewise, Brough et al. (2020) identify that when minorities use SNs they manage to raise awareness among the non-minority public about their experiences (for example, coming from a low-income community, being a first-generation university student, being a person of color or belonging to the LGTBI community) and give rise to their voices. Furthermore, thanks to SNs, minorities have access to news and information with which they identify, since the dominant media often does not cover certain topics or communities of interest to them. Along the same lines, Theben et al. (2021) and Kornbluh (2019) identify that young people using SNs can act as multipliers and facilitators that make community actions visible. SNs also offer an opportunity to generate intergenerational links (Tisdall & Cuevas-Parra, 2022; Nursey-Bray et al., 2022; Newman, 2019), so young people connect with perspectives that they do not know.

The use of SNs also allows young people to obtain references that facilitate inclusion and empower them. For example, in the experience reported by Matenda et al. (2020), most participants use SNs to access financing opportunities in studies, volunteering and work, since key agents share them in their profiles. This is especially important in their case because the population comes from a poverty-stricken area, so the ability to access financing opportunities is important. In the study by Brown et al. (2022), young people who will be first-generation students, as they explored their post-obligatory education options, their online participation allowed them to recognize new and diverse sources of information and social support during the transition. In this case, the referents were other students from their high school a few years older who had recently entered university and followed each other on Instagram. They saw photos of university life on their profiles and could resolve their doubts, which helped them demystify the university experience and deconstruct institutional narratives, seeing different realities and seeing themselves capable of going to university even though their parents they did not. References were also key for rural young people who moved to the city, who saw other references through the stories on SNs of people with the same business, supported them emotionally in complicated times and from whom they learned how to face their challenges (Tulibaleka & Katunze, 2023).

In general terms, most experiences report that SNs generate bonding ties that allow the creation of links to participate in the community, whether it is a local community or exclusively virtual (Dredge & Schreurs, 2020). This is an especially key point in the field of volunteering (Nursey-Bray et al., 2022; Newman, 2019). Former volunteer organizations became bridging organizations that promote bridging between community members and young people. They provide a space for the co-production of knowledge, the building of trust, the creation of common sense, learning, vertical and horizontal collaboration and conflict resolution, promoting social learning opportunities as iterative processes of reflection on the community. Similarly, in the case of Walby & Gumieny (2020), local police establish relationships with the community to generate a feeling of trust and respect, either by creating their own content or interacting with other community organizations on Twitter, such as youth centers and schools. The results report a significant impact on the lives of young people and their participation in the community. Creating links for participation is also important in activism (Chan et al., 2021). Finally, it should be noted that in the case of the existence of an in-person group or local community in general, the bridging links generated in the SNs are transferred to face-to-face (Llena-Berñe et al., 2023).

Linking ties

Linking ties refer to asymmetrical and mostly vertical social relationships between individuals with different spaces of power. In this sense, SNs make it possible to bring together vertical relationships that exist between some agents of the local community/face-to-face group and young people. This is the case of the local police in the experience of Walby & Gumieny (2020), who use them to be more accessible to the community, so that they are informed and participate. In the experience of Kasperski & Blau (2023), the informal nature of communication and access to the more personal than academic dimension that occurs on social networks brings closer the relationships between teachers and students. Consequently, mutual trust increases.

In the case of communities that only exist virtually, SNs help establish vertical relationships that would be inaccessible in an exclusively face-to-face context. For example, they help to get a job, connect with professional contacts or access professional mentors (Brough et al., 2020), as well as connect with key agents in a position of power with the capacity to offer financial support and access decision-making spheres, especially relevant in the field of activism (Yuen & Tang, 2021). Brown et al. (2022) also report key results for minority youth who want to access post-obligatory studies as first-generation students. One of its participants explains that she shared her letter of acceptance to the university on Twitter and other young people advised her to tag the institution. Staff members contacted her and helped in the registration process, and even the rector of the university sent her a direct message through Twitter. This interaction probably would not have occurred without the SN, or at least not in this way of informal communication or in a space of relative horizontality.

4.2.2. Evidence of social capital development

The analysis of the literature reviewed indicates that the use of social networks in virtual communities of young people has proven to be a significant factor in the development of social capital. This development is mainly observed when young people actively participate in these communities with clear and shared goals.

For example, in Kornbluh’s (2019) study, young people use social networks not only to promote their community improvement projects, but also to connect with other institutes, share experiences, and establish collaborations. This activity not only facilitates the expansion of their personal networks, but also strengthens their involvement in the community, providing clear evidence of the development of social capital through these interactions.

Another relevant case is that of Tulibaleka & Katunze (2023), who document how young people migrating from rural areas to the city use social networks to receive support in their adaptation to the new urban environment. Through these platforms, young people obtain key information and maintain contact with their home communities, showing how social capital can be developed and maintained in contexts of significant change.

In a different context, Brough et al. (2020) examine how social networks facilitate the creation of identity-based virtual communities among minority youth. These platforms allow youth to connect with others who share similar experiences and challenges, providing a space for mutual support and empowerment that contributes to the development of social capital in a virtual environment.

In contrast, Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes (2023) present an example where the development of social capital was limited. In their study on the use of the Google+ platform in a virtual community, the authors did not observe significant growth in social capital among young people. They attribute this lack of development to the limited functionalities of the platform and the low perceived usefulness among participants. This case highlights the importance of choosing the right platform to facilitate the development of social capital.

The analysis also evidenced contrasts and exceptions, for example, the study by Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes provides a crucial example of how platforms that are not perceived as useful or that do not adapt well to users’ needs can limit the development of social capital. The lack of interaction and participation in their study suggests that, although social networks have the potential to generate social capital, this development is not automatic and depends on several factors, including platform usability and relevance.

On the other hand, in most of the studies reviewed, it is observed that when young people use platforms that they consider intuitive and valuable, the development of social capital is a common outcome. This highlights the importance of adapting platforms and digital experiences to the expectations and habits of young people to maximize their impact on social capital.

4.2.3. Functionalities of social media platforms that facilitate the development of social capital

The functionalities of social media platforms, from group creation to privacy customization and event organization, are fundamental to facilitating the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people. The choice of platform and the alignment of its features with the needs of users are essential to maximize this positive impact. Each one of them is specified below:

Creation and management of groups

The ability to form and manage groups is critical to bringing together people with common interests in a dedicated space. Facebook is a prominent example, where groups allow users to share content and hold discussions, enhancing cohesion and a sense of belonging (Kasperski & Blau, 2023). WhatsApp also facilitates the creation of groups, where ongoing communication strengthens SC between members (Bano et al., 2019).

Sharing multimedia content

The ability to share photos, videos, and links on platforms such as Instagram and YouTube enrich interaction, helping young people express their identity and connect with others who share similar interests. Brough et al. (2020) show how these visual interactions on Instagram strengthen SC by allowing the creation of shared narratives.

Synchronous and asynchronous communication

Instant messaging and commenting functionalities allow young people to communicate flexibly and continuously. Tools such as direct messages on Instagram and discussions on Facebook facilitate the development of personal relationships and interaction around relevant topics (Matenda et al., 2020; Gureeva et al., 2022).

Personalization and privacy control

The ability to personalize the experience and control privacy is crucial for young people to feel comfortable sharing and participating in virtual communities. Facebook offers advanced privacy options, essential for fostering participation and the development of SC, while less intuitive platforms such as Google+ have shown limitations in this regard (Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes, 2023).

Tools for mobilization and organization

Social media facilitate the organization of events and mobilization around common causes, as is the case with events on Facebook and the use of hashtags on Twitter and Instagram. These tools allow young people to coordinate collective actions and strengthen their SC through participation in social movements (Chan et al., 2021; Yuen & Tang, 2021).

5. Discussion

The results of this systematic review show that social networks play a significant role in the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people, although the magnitude and nature of this contribution depend on various contextual and technological factors. The studies reviewed suggest that, in most cases, SNs facilitate the creation and strengthening of social ties, allowing young people to generate and maintain meaningful relationships, both at a close level (bonding ties) and in broader, but less intense connections (bridging ties).

However, these findings also raise several important questions. For example, it is necessary to explore whether the social capital developed in these virtual communities is sustained in the long term or whether it tends to dissolve once circumstances change. In addition, research is required on how SC development varies in different cultural and geographical contexts, considering that most studies focus on Western contexts. The question also arises as to whether adult intervention, although not essential, could be beneficial in specific situations, such as in more vulnerable communities.

Variability in the nature of experiences

Experiences of developing SC through SNs vary widely, not only in terms of their objectives, but also in terms of the contexts in which they are conducted and the groups of young people involved. While this variability reflects the inherent versatility of SNs, it also suggests that not all platforms are equally effective in all contexts. For example, informal experiences and communities that spontaneously form in SNs tend to be more successful in creating bonding and bridging ties. These results indicate that young people have an innate capacity to use SNs effectively, even in the absence of adult facilitators or specific training, although these elements may enhance outcomes in certain circumstances.

Types of generated social capital

In relation to the types of social capital identified, bonding ties are the most commonly reported, especially in communities where there is prior face-to-face interaction. SNs allow young people to maintain and strengthen these relationships, extending their interaction beyond physical and temporal boundaries. This finding is consistent with existing literature, which points to the capacity of SNs to facilitate ongoing communication and mutual support between members of an existing community (Kasperski & Blau, 2023; Matenda et al., 2020).

On the other hand, bridging ties, which allow for the creation of connections with new people and exposure to different perspectives, are also common in the experiences reviewed. These connections are especially important for young people who participate in virtual communities where there is no equivalent face-to-face group, as SNs allow them to access new opportunities and expand their social network beyond their immediate circle (Gureeva et al., 2022; Brough et al., 2020). Finally, bonding ties, although less frequent, are also observed in contexts where young people need to interact with authority figures or access resources that require a vertical relationship (Walby & Gumieny, 2020; Brown et al., 2022). These ties are crucial in the context of social mobilization and access to educational or professional opportunities.

Functionalities of social network platforms

Specific functionalities of SN platforms play a fundamental role in SC development. The ability to create and manage groups, share multimedia content, and facilitate both synchronous and asynchronous communication are key aspects that determine the effectiveness of a platform in promoting SC. Furthermore, the personalization of the user experience and tools for the organization and mobilization of events are essential to attract and maintain the participation of young people in these virtual communities (Kasperski & Blau, 2023; Chan et al., 2021).

However, the results also indicate that not all platforms are equally effective. The perception of usefulness and ease of use are determinants for the success of a virtual community in SC development. For example, the lack of intuitive and relevant functionalities in Google+ significantly limited the development of SC in the experience reported by Ramos Mancilla & Flores-Fuentes (2023), underlining the importance of a good technological adaptation to the needs of users.

Finally, although SNs have great potential to contribute to the development of social capital in youth virtual communities, their effectiveness depends largely on how these platforms are used, the characteristics of the communities, and the alignment of SN functionalities with the needs of users. Platforms that offer greater flexibility, customization options, and functionalities aligned with the needs of virtual communities are more likely to facilitate robust SC development. Furthermore, although adult interventions and facilitations are not essential, they can enhance the effects in specific contexts, suggesting that a hybrid approach might be the most effective in certain scenarios.

These findings provide a solid foundation for future research and practice in the use of SNs for SC development, especially in youth communities, highlighting the need for conscious, user-centered design to maximize the positive impact of these technologies. Furthermore, it is crucial that future research addresses questions raised, such as the long-term sustainability of social capital, cultural differences in SC development, and the role that adult intervention can play in more vulnerable communities.

6. Conclusion

SN platforms offer opportunities to connect with friends, family, and communities. They have become an integral part of the daily lives of millions of people around the world, so their ability to foster the development of social capital has been explored. The conclusions of how interactions in SNs contribute to the development of social capital in virtual communities of young people are presented below.

Social media platforms in themselves do not develop social capital, it is the interactions that occur online. A key finding is that social media platforms themselves are not directly responsible for the development of social capital. These platforms act as a means to facilitate social interactions, but it is the quality, quantity, and “with whom” of these interactions that truly generate social capital. Thus, SNs enable new links (bridging and linking) and strengthen existing ones (bonding), but they do not do so on their own; they require the agency of their users.

A key element for the development of social capital is motivation, the perception of need. People tend to engage more actively on these platforms when they feel they have a need to connect with others, whether it is to obtain information, emotional support, or satisfy a need of belonging. The motivation to interact on social media is essential to promote the generation of social capital; without it people would not be willing to actively participate and share social resources. This explains that in all successful experiences reviewed, participants are aware of the meaning of their participation in the virtual community.

The development of social capital occurs in both formal and informal experiences. Although it can be thought that formal socio-educational experiences –that is, those that result from a specific intervention mediated by an adult and usually with associated objectives– develop SC above the links that are generated informally between young people, the results demonstrate which is not like that. In fact, the results show that a socio-educational intervention in the form of a virtual community in SNs for young people is not a guarantee of SC development if young people do not perceive the meaning of this community. These results agree with the findings of Úcar & Llena (2006), who identify that both community actions with objectives explicitly aimed at generating social or community effects (formal) and those that do not (informal) can generate these effects.

Contributions

|

Contributions |

Authors |

|

Conception and design of work |

Author 1, 2 |

|

Documentary search |

Author 1 |

|

Data collect |

Author 1 |

|

Critical data analysis and interpretation |

Author 1, 2 |

|

Review and approval of versions |

Author 2, 1 |

Funding

The research did not have funding sources.

Conflict interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Bibliographic References

Bano, S., Cisheng, W., Khan, A. N., & Khan, N. A. (2019). WhatsApp use and student’s psychological well-being: Role of social capital and social integration. Children and youth services review, 103, 200-208. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.06.002

Brough, M., Literat, I., & Ikin, A. (2020). “Good social media?”: underrepresented youth perspectives on the ethical and equitable design of social media platforms. Social Media+Society, 6(2), 2056305120928488. doi: 10.1177/2056305120928488

Brown, M., Pyle, C., & Ellison, N. B. (2022). “On My Head About It”: College Aspirations, Social Media Participation, and Community Cultural Wealth. Social Media+ Society, 8(2), 20563051221091545. doi: 10.1177/20563051221091545

Codina, L. (2021). Scoping reviews: características, frameworks principales y uso en trabajos académicos. (2021, 1 de septiembre). Lluís Codina. https://www.lluiscodina.com/scoping-reviews-guia/

Dredge, R., & Schreurs, L. (2020). Social media use and offline interpersonal outcomes during youth: A systematic literature review. Mass Communication and Society, 23(6), 885-911. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2020.1810277

Guirao Goris, S. J. A. (2015). Utilidad y tipos de revisión de literatura. Ene, 9(2). doi: 10.4321/S1988-348X2015000200002

Gureeva, A., Anikina, M., Muronets, O., Samorodova, E., & Bakalyuk, P. (2022). Media activity of modern Russian youth in the context of value systems1. World of Media. Journal of Russian Media and Journalism Studies, (1), 25. doi: 10.30547/vestnik.journ.5.2021.5173

Junus, A., Kwan, C., Wong, C., Chen, Z., & Yip, P. S. F. (2023). Shifts in patterns of help-seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Hong Kong’s younger generation. Social Science & Medicine, 318, 115648. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115648

Kasperski, R., & Blau, I. (2023). Social capital in high-schools: teacher-student relationships within an online social network and their association with in-class interactions and learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 955-971. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1815220

Kornbluh, M. E. (2019). Building bridges: Exploring the communication trends and perceived sociopolitical benefits of adolescents engaging in online social justice efforts. Youth & Society, 51(8), 1104-1126. doi:/10.1177/0044118X17723656

Llena, A., & Úcar, X. (2006). Acción comunitaria: miradas y diálogos interdisciplinarios. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=10867

Llena Berñe, A., Planas-Lladó, A., Vila-Mumbrú, C., & Valdivia-Vizarreta, P. (2023). Factors that enhance and limit youth empowerment, according to social educators. Qualitative Research Journal, 23(5), 588-603. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-04-2023-0063

Martínez, L. M., & Úcar, X. (2022). The generation of community social capital in the Poble Sec community plan (Barcelona). Community Development, 53(4), 477-498. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2021.1987487

Matenda, S., Naidoo, G. M., & Rugbeer, H. (2020). A study of young people’s use of social media for social capital in Mthatha, Eastern Cape. Communitas, 25, 1-15. doi: 10.18820/24150525/Comm.v25.10

Newman, M. (2019). Linking 4-H to Linksters. The Journal of Extension, 57(3), 21. doi: 10.34068/joe.57.03.21

Nursey-Bray, M., Masud-All-Kamal, M., Di Giacomo, M. & Millcock, S. (2022). Building community resilience through youth volunteering: towards a new model. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 242-263. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2022.2067004

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Ramos Mancilla, Ó. y Flores-Fuentes, G. (2023). Educación informal y entornos digitales entre jóvenes de comunidades indígenas. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 25. doi: 10.24320/redie.2023.25.e05.4298

Soler Masó, P., Trilla Bernet, J., Jiménez Morales, M., & Úcar Martínez, X. (2017). La construcción de un modelo pedagógico del empoderamiento juvenil: espacios, momentos y procesos. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 30, pp. 19-34. doi: 10.7179/PSRI_2017.30.02

Theben, A., Juárez, D. A., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Peña-López, I., & Porcu, F. (2021). Participación y ciudadanía activa de los jóvenes a través de Internet y las redes sociales. Un estudio internacional. BiD: Textos universitarios de biblioteconomía y documentación, (46), 3. doi: 10.1344/BiD2020.46.01

Tisdall, E. K. M. & Cuevas-Parra, P. (2022). Beyond the familiar challenges for children and young people’s participation rights: the potential of activism. The International Journal of Human Rights, 26(5), 792-810. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2021.1968377

Tulibaleka, P. O. & Katunze, M. (2023). Rural-Urban Youth Migration: the Role of Social Networks and Social Media in Youth Migrants’ Transition into Urban Areas as Self-employed Workers in Uganda. In Urban Forum (pp. 1-20). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi: 10.1007/s12132-023-09494-y

Valdivia, P., Úcar, X., & Ciraso Calí, A. (2022). Integrar a jóvenes adultos/as con menos oportunidades en las organizaciones y reforzar su empoderamiento. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/275804?ln=ca

Walby, K., & Gumieny, C. (2020). Public police’s philanthropy and Twitter communications in Canada. Policing: An International Journal, 43(5), 755-768. doi: 10.1177/14614448211015805

Wong, B. (May 18th, 2023). Top Social Media Statistics And Trends Of 2024. Forbes Advisor. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/social-media-statistics/#source

Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. The world bank research observer, 15(2), 225-249. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/67567/SocialCapital.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Yuen, S., & Tang, G. (2021). Instagram and social capital: youth activism in a networked movement. Social Movement Studies, 1-22. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2021.2011189

HOW TO CITE THE ARTICLE

|

Alguacil, L. y Valdivia-Vizarreta, P. (2025). Redes sociales y vínculos: revisión sistemática (PRISMA) sobre el impacto del capital social en comunidades de jóvenes. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 46, 209-227. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2025.46.12 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

Laia Alguacil Mir. Departamento de Pedagogía Aplicada, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Edificio G6-Despacho 270. Campus de Bellaterra, c.p. 08193, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona. E-mail: Laia.Alguacil@uab.cat Paloma Valdivia-Vizarreta. Departamento de Teorías de la Educación y Pedagogía Social, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Edificio G6-Despacho 171. Campus de Bellaterra, c.p. 08193, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona. E-mail: paloma.valdivia@uab.cat |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

LAIA ALGUACIL MIR https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5562-5093 Graduada en Maestro de Educación Infantil y Maestro de Educación Primaria con Mención en Lenguas Extranjeras por la Universitat de Barcelona (2016-2021). Ha realizado el Máster de Investigación en Educación en la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (2022-2023) y, en la actualidad, es investigadora predoctoral en el marco de las Ayudas FPU del Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. Inició el contacto con la investigación mediante contratos de colaboración, en 2017, en el departamento de Didáctica y Organización Educativa de la Universitat de Barcelona. En 2021 se vinculó al CRiEDO como técnica de apoyo a la investigación, centro de investigación donde continúa desarrollando su actividad científica. PALOMA VALDIVIA-VIZARRETA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1499-5478 Profesora lectora Serra Húnter, en el Departamento de Teorías de la Educación y Pedagogía Social de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Licenciada en Educación Primaria (Universidad UNIFE-Perú), Magíster en Planificación y Gestión Educativa y Doctora en Ciencias de la Educación. Su docencia e investigación se centran en la pedagogía social, el ocio, el uso educativo y social de las TIC y el desarrollo de redes comunitarias, en el contexto de una educación abierta y flexible a lo largo de la vida, universitaria y comunitaria. Forma parte del grupo de investigación SGR IJASC (Infancia y Juventud: Educación social y acción comunitaria). 15 años de experiencias en centros educativos y 9 en proyectos socioeducativos de innovación social digital. |