eISSN: 1989-9742 © SIPS. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2024.45.13

http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/

Versión en español: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/PSRI/article/view/101392/78884

Perception and experiences of University of Salamanca students about leisure and free time

Percepción y experiencias de los estudiantes de la Universidad de Salamanca

sobre el ocio y el tiempo libre

Percepções e experiências de estudantes universitários de Salamanca sobre

lazer e tempo livre

María Cruz SÁNCHEZ-GÓMEZ  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4726-7143

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4726-7143

Juan Luis CABANILLAS-GARCÍA  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8458-3546

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8458-3546

Sonia VERDUGO-CASTRO  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9357-1747

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9357-1747

University of Salamanca

Received date: 12.VIII.2023

Reviewed date: 30.X.2023

Accepted date: 23.III.2024

CONTACT WITH THE AUTHORS

Juan Luis Cabanillas García: Dto de Didáctica, Organización y Métodos de Investigación. Universidad de Salamanca. Paseo de Canalejas 169, C.P. 37008, Salamanca.E-mail: jluiscabanillas@usal.es.

|

KEYWORDS: Educational leisure; higher education; habits; content analysis; healthy activities |

ABSTRACT: Research on university students’ leisure is relevant because it provides crucial insights for designing educational and social interventions that promote a healthy balance between academic pursuits and the overall well-being of young people in contemporary society. Thus, the study aimed to investigate the typology, conceptualization, accessibility, and demands of the University of Salamanca students regarding their leisure and free time. A qualitative methodology was applied, focusing on capturing students’ subjective experiences and interpretations through the analysis of narratives derived from open-ended questions in a specially designed questionnaire, considering the reviewed literature. The sample consisted of 487 students from the University of Salamanca. After conducting content analysis with the assistance of Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis NVivo12, it is concluded that the majority consider their leisure time related to health, with predominantly healthy habits, experiencing satisfaction, relaxation, release, and enjoyment, engaging primarily in group sports activities, along with music-related activities, cultural events, attending talks and conferences, cultural visits, and volunteering. Additionally, they express a demand for increased travel and excursions, as well as social activities for socializing. Finally, researching this reality from the perspectives of pedagogy and social education is fundamental for applying participatory pedagogical approaches and intervention strategies that promote students’ personal and social development, thus fostering an inclusive and enriching leisure culture. |

|

PALABRAS CLAVE: Ocio educativo; educación superior; hábitos; análisis de contenido; actividades saludables |

RESUMEN: La investigación sobre el ocio del alumnado universitario es pertinente porque proporciona insights cruciales para diseñar intervenciones educativas y sociales que promuevan un equilibrio saludable entre el ámbito académico y el bienestar integral de los/as jóvenes en la sociedad contemporánea. Así, el estudio presentando proponía averiguar la tipología, la conceptualización, la accesibilidad y las demandas del alumnado de la Universidad de Salamanca con respecto a su ocio y tiempo libre. Se aplicó la metodología cualitativa, donde el foco de información se centró en captar las experiencias e interpretaciones subjetivas del alumnado mediante el análisis de narrativas procedentes de preguntas abiertas de un cuestionario elaborado ad hoc considerando la literatura revisada. La muestra quedó constituida por 487 discentes de la Universidad de Salamanca. Tras la realización del análisis de contenido con ayuda del Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis NVivo12, se concluye que la mayoría considera que su tiempo de ocio está relacionado con la salud y que sus hábitos tienden a ser saludables, sienten satisfacción, relajación, liberación y diversión, participan preferentemente en actividades deportivas, más en grupo que individualmente, junto con actividades vinculadas a la música, actividades culturales, asistencia a charlas y conferencias, visitas culturales y voluntariado. También, demandan aumento de viajes y excursiones, junto a las actividades sociales de convivencia. Finalmente, investigar esta realidad desde la pedagogía y la educación social es fundamental para aplicar enfoques pedagógicos participativos y estrategias de intervención que fomenten el desarrollo personal y social del estudiantado, promoviendo así una cultura del ocio inclusiva y enriquecedora. |

|

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Lazer educativo; educação superior; hábitos; análise de conteúdo; atividades saudáveis |

RESUMO: A investigação sobre o tempo livre dos estudantes universitários é relevante porque fornece informações cruciais para a conceção de intervenções educativas e sociais que promovam um equilíbrio saudável entre o ambiente académico e o bem-estar geral dos jovens na sociedade contemporânea. Assim, o presente estudo teve como objetivo conhecer a tipologia, a concetualização, a acessibilidade e as exigências dos estudantes da Universidade de Salamanca em relação ao seu tempo livre e de lazer. Aplicou-se a metodologia qualitativa, onde o foco da informação foi a captação das experiências subjectivas e interpretações dos estudantes através da análise de narrativas a partir de questões abertas de um questionário elaborado ad hoc tendo em conta a literatura revista. A amostra foi constituída por 487 estudantes da Universidade de Salamanca. Após a realização da análise de conteúdo com a ajuda do programa Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis NVivo12, concluiu-se que a maioria considera que o seu tempo livre está relacionado com a saúde e que os seus hábitos tendem a ser saudáveis, sentem satisfação, relaxamento, libertação e diversão, participam preferencialmente em actividades desportivas, mais em grupo do que individualmente, juntamente com actividades relacionadas com a música, actividades culturais, participação em palestras e conferências, visitas culturais e voluntariado. Exigem também um aumento das viagens e excursões, bem como das actividades sociais. Finalmente, a investigação desta realidade na perspetiva da pedagogia e da educação social é essencial para aplicar abordagens pedagógicas participativas e estratégias de intervenção que favoreçam o desenvolvimento pessoal e social dos alunos, promovendo assim uma cultura de lazer inclusiva e enriquecedora. |

1. Introduction

Leisure is defined as those practical and freely chosen activities directed towards self-realization, fun, or relaxation (Rodríguez Suárez & Agulló Tomás, 1999). Also, it can be defined as “a way of using free time through a freely chosen and rewarding occupation, whose development is satisfying or pleasurable for the individual” (Andrés-Villas et al., 2020, p.1). Consequently, it can be understood that leisure has importance and impact in people’s lives, as it is the time that can be used to grow and satisfy social and personal needs. In this sense, “it has been shown that, especially, active leisure contributes to maintaining adequate physical and mental fitness” (Sarrate Capdevila, 2008, p. 3).

In relation to youth and leisure time, contemporary young people are immersed in a dynamic sociocultural environment that significantly influences their perception and experience of leisure and free time (Hasanpour et al., 2023). In an era marked by technological advancements, changes in family and work structures, as well as transformations in cultural consumption patterns, youth are faced with a variety of options and challenges when it comes to dedicating time to non-obligatory activities (Hemming & Tillmann, 2023). This life stage is characterized by a search for identity, autonomy, and pleasure, where leisure becomes a space for exploration, expression, and social connection (Lenze et al., 2023).

Within the broad group of youth, young university students represent a particularly interesting group for the study of leisure and free time (Woodward et al., 2023). As individuals in a crucial stage of transition into adulthood, they face demanding academic requirements but also a wide range of opportunities for personal and social development (Kinder et al., 2023). The university experience not only involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills but also the building of support networks, the exploration of interests and passions, and the consolidation of identity. Thus, it is indisputable the relevance of understanding how students conceptualize and experience leisure and free time, to design strategies that promote their overall well-being and full development during this crucial stage of their academic and personal lives.

Some of the studies being conducted internationally on leisure choices made by university students include research on gender differences in these choices (Gómez-Mazorra et al., 2023), the impact of COVID-19 on the normal development of leisure activities (Turkmani et al., 2023), the relationship between leisure and education (Kono et al., 2024), and the perception of boredom (Labuschagne et al., 2023).

In Spain, the study of leisure has gained relevance over the years thanks to initiatives such as Red OcioGune and the Institute of Leisure Studies at the University of Deusto, which have significantly contributed to the analysis and promotion of this multidimensional field (Caballo Villar et al., 2018). These entities have addressed leisure as a complex phenomenon that goes beyond mere entertainment, recognizing it as a crucial component for individual and social well-being.

Within the whole framework between leisure and its options, Pedagogy and Social Education emerge, as from a pedagogical perspective, leisure becomes fertile ground for the application of active and participatory methodologies that encourage critical reflection, creativity, and autonomy (Kono et al., 2024). Additionally, social education finds opportunities to intervene preventively in the leisure realm, promoting values of inclusion, equality, and well-being through playful and recreational activities. In this sense, the integration of leisure and free time into educational and social processes emerges as a powerful resource to enhance human development and contribute to the construction of a fairer and more equitable society.

Taking all of this into account, one of the greatest benefits of using leisure time in enriching activities for personal development is that “the close relationship that occurs between participating in leisure activities, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction to counteract daily life problems” has been demonstrated (Sarrate Capdevila, 2008, p.3). The study conducted by Sandoval Acuña (2017), diagnosing the use of leisure and free time among students at the Universidad Nacional Experimental de Táchira (Venezuela), infers that students associate the concept of leisure with “wasting time” or “idleness”, having a negative connotation, while the term “free time” is more linked to “productive” activities. The negative association with the word “leisure” may be due to cultural influences, as in certain regions it is associated with the idea of “laziness” or “loafing”, and some students interpret it as doing “unproductive” things.

Regarding the typology of consumed leisure, this may vary depending on the different factors of the individuals who consume it, although it is worth noting that Spanish universities, currently, within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, “are considered promoters of health, defined as places that constantly reinforce their capacity as healthy places to live, learn, and work” (López-Alonso et al., 2021, p. 1). Additionally, López-Alonso et al. (2021) assert that those who engage in healthy or active leisure tend to have a better perception of their health and, in turn, a greater commitment to their studies or work activities.

In a study conducted by Agans et al. (2022) with university students in the United States regarding the practice of healthy and unhealthy leisure, it was concluded that all the students who participated were able to classify healthy and unhealthy leisure options, prompting the need for interventions to promote different methodologies for engaging in healthy leisure alternatives. In this line, among the preferences for leisure activities of university students, Andrés-Villas et al. (2020) highlight that 93 % of the studied group preferred to spend their free time listening to music, going out with friends (92.7 %), using the computer (88.8 %), exercising (78 %), resting/doing nothing (78 %), watching television (77.9 %), going to museums or exhibitions (27 %), going to the theatre (26.7 %), and attending conferences/discussions (20.1 %).

Other studies emphasize that young university students place greater importance on sports and socializing with their peers when investing their leisure time, as opposed to engaging in cultural activities (Cordero Domínguez & Aguilar Luna, 2015; Hernández Prados & Álvarez Muñoz, 2020). However, leisure activities involving digital media have become increasingly prevalent among university students, as the study conducted by López-Alonso et al. (2021) concludes that young people spend their free time chatting on social networks or the internet. In Spain alone, the daily use of the internet among young people aged 16 to 35 exceeds 90 %. This type of leisure allows them to interact with both people from their immediate surroundings and those they do not know, have no relationship with, or are far removed from their circle of friends. Furthermore, they believe that the use of social media is an easy, quick, and effective way to socialize, and internet access is a defining and highly prevalent element in the lives of young people.

It should be noted that certain issues related to leisure among university students have been identified. Suárez et al. (2021) argue that in the early years of university life, alcohol and tobacco consumption is more common, although it begins to decrease in the later years, with an increased interest in physical activity. As they progress in their academic and social maturity, they realize that there is a range of healthy leisure activities available within their institution that helps enrich their free time.

Regarding the unhealthy leisure options consumed by university students, López-Cisneros et al. (2021) conducted a study at the University of Sonora (Mexico) aiming to examine the relationship between personality traits and alcohol consumption during leisure time. One finding highlights that youth begin their consumption at the age of 17. This is primarily due to being in a transitional period between adolescence and adulthood, where they seek independence and aim to feel like members and participants in their own behaviors, values, norms, principles, habits, customs, and trends. In this regard, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated in the World Health Report on Alcohol and Health that 3.3 million people die each year due to this addiction (WHO, 2018).

On the other hand, in the study conducted by Navarro-Pérez et al. (2015) in Valencia (Spain) on adolescent student population, it was revealed that 79.8 % of the respondents admitted to having consumed addictive substances. 22.4 % admitted to consuming alcohol and marijuana, 12.6 % alcohol and tobacco, 9.3 % alcohol and amphetamines, 6.2 % alcohol and cocaine, 2.9 % marijuana and amphetamines, and 1.8 % other combinations of addictive substances. This study shows how alcohol is one of the most problematic substances consumed by this population, as it helps them overcome their introversion and difficulties in interacting with people they do not know or trust.

Therefore, investigating the leisure preferences of university students should be a fundamental objective for institutions, in order to offer quality healthy leisure alternatives that adapt to their tastes and hobbies. This can contribute to reducing the consumption of unhealthy leisure, which can lead to serious consequences in their personal and educational performance.

In the context of this purpose, the present study arises from the Innovation and Teaching Improvement Project of the University of Salamanca (USAL) for the academic year 2021/2022, named “Healthy Leisure for University Student Population (ID2021/172)”. The general objective pursued by this project is to investigate the typology, conceptualization, accessibility, and demands of USAL students regarding their leisure and free time. To achieve this, research questions are defined related to the conceptualization of leisure and free time by USAL students, as well as the barriers to their enjoyment, the availability of healthy activities, the impact of COVID-19, the quality of the university’s leisure offerings, predominant habits, and the influence of gender and age on these perceptions and practices. Additionally, this study takes into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ leisure, following the international research lines of other studies such as that of Woodrow & Moore (2021), which considered the impact in the United Kingdom.

2. Objectives and research questions

The development of this work is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals on Health and Well-being and Quality Education. It comprehensively addresses the challenges of sustainable education systems and recognizes the inseparable links between healthy individuals, societies, and a healthy planet.

The salutogenic theory is a model of socio-health promotion that views individuals as active subjects capable of increasing control and improving their physical, mental, and social health. Community assets or resources for socio-health attitudes are those human, social, educational, physical, or environmental resources that enhance the capacity to maintain, preserve, and generate health and well-being (Sánchez-Casado et al., 2017).

The aim of asset mapping, in addition to providing visibility and value to all the structures and actions available at the University of Salamanca (USAL) that contribute to quality of life, should serve as a tool for community participation within the framework of social responsibility. From this perspective, the following research questions were formulated for the study:

· How does the student body at USAL conceptualize leisure and free time? (RQ1)

· What prevents students from engaging in and enjoying leisure activities? (RQ2)

· What availability do students have to engage in healthy leisure activities? (RQ3)

· How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the leisure of university students? (RQ4)

· Is the offering of healthy leisure activities by USAL adequate or does it need further depth and improvement? (RQ5)

· What are the predominant healthy and unhealthy habits among students? (RQ6)

· Are gender and age key factors in defining personal leisure and free time as well as that of USAL? (RQ7)

From the research questions arises the general objective of the investigation, which was to ascertain the typology, conceptualization, accessibility, and demands of USAL students regarding their leisure and free time. To achieve this objective, the following specific objectives were formulated:

· Investigating the concept of leisure and free time (SO1).

· Determining the reasons for abstaining from engaging in leisure activities (SO2).

· Identifying the main environments and places available for students to engage in healthy leisure activities (SO3).

· Investigating how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected students’ leisure (SO4).

· Exploring the activities offered by USAL to students, aimed at promoting healthy leisure (SO5).

· Defining opportunities for improving the offering and dissemination channels of healthy leisure activities provided by USAL (SO6).

· Observing standards of healthy and unhealthy habits among students (SO7).

· Exploring differences between genders and age groups in the perception of personal leisure and free time as well as that available at USAL (SO8).

3. Methodology

This research has been shaped from the interpretative paradigm with a qualitative methodology based on content analysis (Verdugo-Castro, 2019), where the experiences and perceptions of university students were analyzed based on their knowledge and reference framework. This type of analysis, according to Bardín (2002), is defined as the set of textual analysis strategies aimed at obtaining indicators (whether quantitative or not) through the use of systematic and objective procedures describing the content of messages, allowing the inference of knowledge related to the production conditions (inferred variables) of these messages. In this case, a thematic content analysis has been carried out. This model focuses solely on the presence of terms or concepts without considering the relationships between them. Common techniques include the use of frequency lists, identification and classification of themes, as well as searching for words in context, and then examining units of analysis more deeply on a specific theme. For this, it is necessary to define and contextualize the topic before conducting the analysis (Andréu, 2002).

The population of the presented work was the student community of USAL during the academic year 2021/2022. It is a finite population which, based on the latest records, is estimated to range between 25,000 and 30,000 students enrolled across different levels: Undergraduate, Master’s, Doctorate, and Professional Titles. Through the snowball sampling technique, 487 USAL students were accessed, with the following profile: 123 males (25.26 %) and 364 females (74.74 %). Of these, 150 were first-year students (30.80 %), 141 were second-year students (28.95 %), 46 were third-year students (9.45 %), 126 were fourth-year students (25.87 %), and 23 were Master’s students (4.72 %). Regarding their faculties of origin, most faculties are represented in the sample, with higher participation from the Faculties of Education, Law, Social Sciences, Psychology, and Fine Arts.

Within the framework of the Innovation and Teaching Improvement Project of USAL for the academic year 2021/2022, titled “Healthy Leisure for University Student Population (ID2021/172)”, a questionnaire of open-ended questions was designed. This questionnaire was based on the methodological guide for the development of a health assets map aimed at health promotion professionals from the Castilla y León Health Council (Consejería de Sanidad Castilla y León, 2022). The purpose was to address the knowledge and perception of USAL student population regarding leisure and free time, as well as the leisure offerings promoted by USAL. Furthermore, its construction is supported by Kretzmann & McKnight (1993), who identify five dimensions for the construction of health and education asset maps, based on reflection on two approaches: abundance and scarcity:

· Individual assets (individuals, knowledge, and their skills).

· Collective assets (projects and resources self-managed by organizations, associations, groups).

· Institutional assets (projects developed by the University).

· Physical environment assets (green spaces, sports facilities, etc.).

· Cultural assets.

All members of the research team for the project, composed of twelve researchers from different areas of expertise (education, psychology, social sciences, and biology), have participated in the construction and validation of the questionnaire1 from an interdisciplinary perspective. Two dimensions have been used for evaluating the open-ended questions of the questionnaire: adequacy (whether the item is correctly formulated) and relevance (whether the item corresponds to the objectives intended to be achieved with the research), along with a descriptive open-ended assessment for improvement of each. The questionnaire was digitized using the Google Forms application for better distribution and accessibility, as the target population for the study is university students, who are digitally active and generally face difficulties in completing traditional paper-based surveys. Initially, the questionnaire was completed by students from the Social Education and Pedagogy programs, who then disseminated the questionnaire to their friends and acquaintances from other faculties through instant messaging applications and email. In this way, and thanks to the involvement of students in the project, access to a sample that offers a holistic view of the phenomena under study was possible.

The Teaching Innovation Project was approved by the Ethics Committee of USAL and the Vice-Rectorate of Transfer, following the protocol of good research practices established, with special mention of compliance with planning protocols, procedures and methodological rigor, environment, infrastructure, and compliance, financing management, audit and monitoring, safety, and health. The questionnaire responses have been analyzed in aggregate form, respecting the General Data Protection Regulation, and in the invitation email for completion, participants were informed of this Regulation and requested informed consent for participation.

Data analysis was supported by Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDAS), specifically using NVivo version 12.0. The data treatment followed the classic system of qualitative data analysis (García-Toro et al., 2020). This model involved the following steps:

1. Data reduction. Information was divided into units of grammatical content (paragraphs and sentences). An inductive content analysis was conducted (developing categories from reading), analysis of collected material without considering categories, and deductive content analysis (categories are established a priori, and the researcher adapts each unit to an existing category). Evaluation of contents belonging to the corresponding category/subcategory was based on two levels, intra-coder and inter-coder, until agreement was reached among members of the research team (García-Peñalvo et al., 2018; Chirico et al., 2021).

2. Disposition and grouping. Various graphic resources and information were obtained using NVivo as follows: relationships and deep structure of the text, graphic representations or visual images of relationships between concepts, and matrices/cross-tabulations including verbal information according to specified aspects by rows and columns. For calculating the frequency of occurrence of categories and subcategories, the NVivo coding matrix exploration tool was used, developing a matrix per category (Marques-Sule et al., 2022; Serrano et al., 2023).

3. Results obtaining and conclusion verification. This phase involved the use of metaphors and analogies, as well as inclusion of vignettes and narrative fragments, culminating with the mentioned triangulation strategies, conducting processes of textual data analysis, description, interpretation, code counting, concurrence, comparison, and contextualization. To transform data into numerical values, statistical techniques for comparison and contextualization were used (Cabanillas-García et al., 2022).

On the other hand, a category table was constructed for the development of content analysis of textual data, consisting of four metacategories, eleven categories and one hundred and thirty-eight subcategories (Table 1):

|

Table 1: Table of categories |

||||

|

Research questions (RQ) |

Specific objectives (SO) |

Metacategories (MC) |

Categories (C) |

Subcategories (SC) |

|

RQ1: How do USAL students conceptualize leisure and free time? |

SO1: Inquire about the concept they have of leisure and free time |

MC1: Analysis and perception of leisure and personal free time: This MC covers the analysis of leisure and free time, from a personal perspective of the student himself, including his vision of the concept, the main reasons why he gives up doing leisure activities. leisure or enjoying your free time, the places available within your immediate environment for leisure activities and how the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has affected your leisure and free time |

C1.1 Concept and usefulness of leisure and free time: How leisure and free time are understood and conceptualized and why young university students usually use it preferentially |

SC1.1.1 Voluntary processes or actions SC1.1.2 Fun and enjoyment SC1.1.3 Mental health SC1.1.4 Rest SC1.1.5 Carry out hobbies SC1.1.6 Disconnect SC1.1.7 Relax SC1.1.8 Socialization SC1.1.9 Physical health SC1.1.10 Space outside of mandatory or routine tasks SC1.1.11 Personal time SC1.1.12 To train SC1.1.13 For distraction and entertainment SC1.1.14 Very important and fundamental SC1.1.15 A necessity SC1.1.16 Promotion of creativity SC1.1.17 To work SC1.1.18 Avoid, evade or forget problems and worries SC1.1.19 Improve quality of life SC1.1.20 Does not know how to define it SC1.1.21 Positive actions SC1.1.22 Activities that motivate me |

|

RQ2: What prevents students from being able to do and enjoy leisure? |

SO2: Determine the causes of renunciation of carrying out leisure activities |

C1.2 Reason for giving up leisure activities: Main aspects, causes or aspects that prevent them from carrying out leisure activities and having to invest their free time in other types of activities |

SC1.2.1 Lack of time SC1.2.2 High teaching load SC1.2.3 I do not enjoy the activity SC1.2.4 There are other activities that I consider more important SC1.2.5 Lack of economic resources SC1.2.6 I do not give up leisure activities SC1.2.7 I don’t like the activity SC1.2.8 I don’t feel like doing the activity SC1.2.9 Laziness SC1.2.10 Fatigue SC1.2.11 I put my obligations first SC1.2.12 Work SC1.2.13 Injury or health problems SC1.2.14 Personal problems SC1.2.15 I am bored with the activity SC1.2.16 Meteorology SC1.2.17 Lack or loss of interest in the activity SC1.2.18 Lack of motivation SC1.2.19 The activity does not benefit me SC1.2.20 I don’t know how to explain SC1.2.21 Lack of company to carry out the activity SC1.2.22 Cannot be done in the city SC1.2.23 Due to negative emotions or feelings |

|

|

RQ3: What availability do students have to carry out healthy leisure activities? |

SO3: Establish the main environments and places available to students to carry out healthy leisure activities. |

C1.3 Nearby places for leisure: Environments available for carrying out healthy leisure activities close to your residence or home during the course of the academic year |

SC1.3.1 Parks or gardens SC1.3.2 Multi-sports courts SC1.3.3 Bars, cafes or restaurants SC1.3.4 Gyms SC1.3.5 Libraries SC1.3.6 Historic center of the city SC1.3.7 University SC1.3.8 Cinemas SC1.3.9 theatres SC1.3.10 Museums SC1.3.11 Nightclubs SC1.3.12 City Council SC1.3.13 Commercial spaces SC1.3.14 I have many spaces and options SC1.3.15 Youth Center SC1.3.16 Playroom SC1.3.17 Swimming pool SC1.3.18 Game rooms SC1.3.19 My classmates’ house SC1.3.20 Neighborhood Association SC1.3.21 Academies SC1.3.22 Bike lane SC1.3.23 University residence |

|

|

RQ4: How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the leisure of university students? |

SO4: Find out how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected student leisure |

C1.4 How the pandemic has affected leisure and free time: Brings together the different assessments of students on how the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has affected the way they carry out leisure activities |

SC1.4.1 Solitary leisure SC1.4.2 Leisure in closed spaces SC1.4.3 Leisure time is valued and used more SC1.4.4 Outdoor leisure SC1.4.5 I have discovered new forms of leisure SC1.4.6 I value physical well-being more SC1.4.7 I value mental well-being more SC1.4.8 Fewer social relationships SC1.4.9 I value the little things more SC1.4.10 I value the company of close people more SC1.4.11 Normality has returned to leisure SC1.4.12 Increased attendance at nightclubs SC1.4.13 Enjoy the moment more SC1.4.14 I value being able to go outside more SC1.4.15 Caution and limitations in leisure due to COVID-19 |

|

|

RQ3: What availability do students have to carry out healthy leisure activities? |

SO3: Establish the main environments and places available to students to carry out healthy leisure activities. |

MC2: Analysis and perception of leisure and free time at USAL: This MC covers the analysis of leisure and free time linked to the resources, spaces and activities available at USAL for leisure, along with suggestions and proposals for improvement within from the university environment |

C2.1 Places available for leisure at USAL: Spaces and infrastructure available at USAL for carrying out healthy leisure activities that are known to students |

SC2.1.1 Language Academy SC2.1.2 Music Academy SC2.1.3 Classrooms SC2.1.4 Libraries SC2.1.5 Coffee shops SC2.1.6 USAL Campus SC2.1.7 Faculties SC2.1.8 Gym SC2.1.9 Sports facilities SC2.1.10 I don’t know the leisure areas at USAL SC2.1.11 Social Affairs Service Office SC2.1.12 Swimming pool SC2.1.13 Exhibition rooms SC2.1.14 Theatre SC2.1.15 Psychological care unit SC2.1.16 Garden areas SC2.1.17 Common work areas |

|

RQ5: Is the offer of healthy leisure activities carried out by USAL adequate or does it need greater depth and improvements? |

SO5: Explore the activities offered by USAL to students aimed at practicing healthy leisure |

C2.2 Healthy leisure activities offered by USAL: Characterization of the diversity of activities offered by USAL for the realization of healthy leisure by students and that are known to them |

SC2.2.1 Activities linked to music SC2.2.2 Activities linked to psychology SC2.2.3 Theatrical performances SC2.2.4 Cinema SC2.2.5 Reading club SC2.2.6 Contests SC2.2.7 Support programs SC2.2.8 Conferences and talks SC2.2.9 Courses, training programs and seminars SC2.2.10 Discussions SC2.2.11 Team sports SC2.2.12 Individual sports SC2.2.13 Exhibitions SC2.2.14 Excursions and trips SC2.2.15 Faculty parties SC2.2.16 Maintenance gymnastics, pilates, aerobics, etc. SC2.2.17 Research conferences SC2.2.18 I do not know the healthy leisure activities of the USAL SC2.2.19 USAL bicycle loan SC2.2.20 Language programs SC2.2.21 Bicycle routes SC2.2.22 Hiking SC2.2.23 Rector Trophy SC2.2.24 Cultural guided tours SC2.2.25 Volunteering |

|

|

RQ5: Is the offer of healthy leisure activities carried out by USAL adequate or does it need greater depth and improvements? |

SO6: Define the possibilities of improving the offer and the channels of dissemination of healthy leisure activities offered by the USAL |

C2.3 Suggestions to improve healthy leisure at USAL: Contributions and evaluations made by students, to improve the quality and supply of healthy leisure activities offered by USAL |

SC2.3.1 Free or discounted activities SC2.3.2 Novel activities SC2.3.3 Release of teaching load SC2.3.4 Greater volume of activities SC2.3.5 Improve communication channels for activities SC2.3.6 I don’t have suggestions or I don’t know what to contribute SC2.3.7 Ask students for their opinion SC2.3.8 Linked to social activities SC2.3.9 Linked to infrastructure SC2.3.10 Linked to art, music and cinema SC2.3.11 Linked to sports activity SC2.3.12 Linked to training SC2.3.13Linked to video games |

|

|

RQ6: What are the predominant healthy and unhealthy habits among students? |

SO7: Observe the standards of healthy and unhealthy habits in students |

MC3: Student habits |

C3.1 Healthy habits: Behaviours and activities that promote physical, mental and emotional well-being during leisure time |

|

|

Q7: Are gender and age key factors when defining personal and USAL leisure and free time? |

SO8: Investigate the differences between men and women and according to age in the perception of leisure and personal free time and that available in the USAL |

MC4: Differences by gender and age |

C3.2 Unhealthy habits: Actions or practices that can harm physical, mental or emotional health while enjoying free time |

|

|

C4.1 Differences by gender C4.2 Differences by age |

||||

4. Results

4.1. Analysis and perception of personal leisure and free time

In this section, we will analyze MC1 to describe how students conceptualize leisure and free time, their knowledge about it, and its most relevant uses. We’ll also explore the reasons that prevent them from engaging in leisure activities, the main environments and nearby places for leisure activities, and how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their leisure.

4.1.1. Concept and utility of leisure and free time

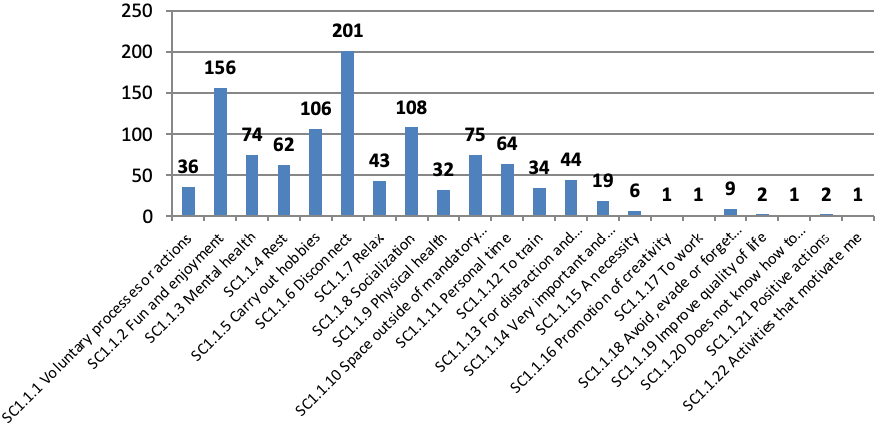

Linked to C1.1: Concept and utility of leisure and free time, it can be observed in Figure 1 that, for university students, leisure implies disconnecting (201 references) from the daily routine, the stress of academic or personal workload, being a key moment to clear their heads. At the same time, they show that it involves fun and enjoyment (156 references), being pleasurable activities that allow them to have a good time and include a socializing aspect (108 references) with family, friends, partners, and those people who truly fulfill and are loved by them, as well as meeting new people or helping those in need, being something natural in human beings.

Furthermore, students specify that it is also a time for rest (108 references), recovering energy to continue with daily activities and being a time away from their mandatory tasks (75 references). Additionally, they also emphasize that leisure activities help improve their mental health (74 references), clearing the mind, helping to feel comfortable with themselves, and improving mood. It is noteworthy that, for the majority of students, there is no distinction between the concepts of leisure and free time, with less than 10 % of students giving a different conceptualization of leisure and free time.

Figure 1. C1.1: Concept and utility of leisure and free time. Source: own elaboration.

4.1.2. Reasons for abstaining from leisure activities

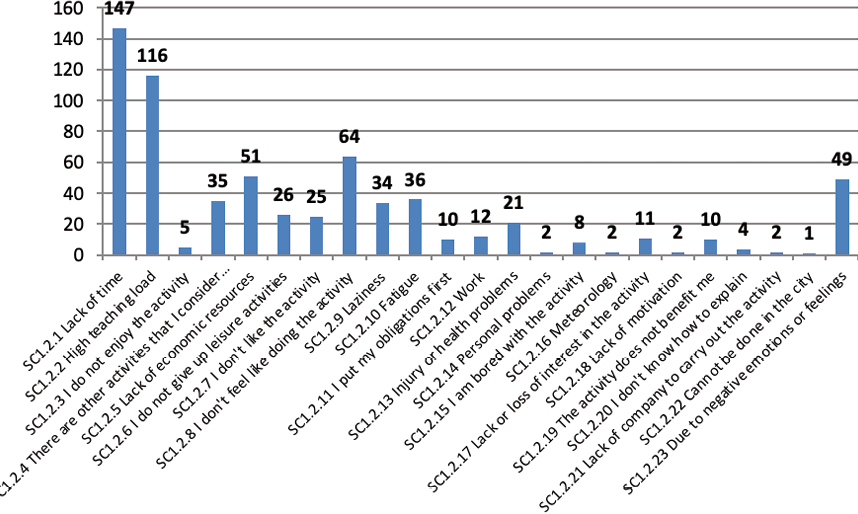

Regarding C1.2: Reasons for renouncing leisure activities, it can be observed in Figure 2 that the main reasons why students do not invest their free time in leisure activities are lack of time (147 references). Currently, university students must invest a significant amount of time in various obligations, both academic, as they have a heavy academic workload (116 references), and family-related. However, this lack of time often arises from poor task organization.

It has also been observed that factors such as not feeling like doing the activity (64 references), laziness (34 references), fatigue (36 references), and negative emotions and feelings (49 references) such as reflected by students “social pressure”, “anxiety”, “not feeling comfortable”, “discouragement”, “stress”, etc., limit their engagement in leisure activities. As observed in the previous point, leisure activities require motivation, fun, enjoyment, and entertainment, and if a person does not consider that the activity will bring these benefits, they may decide not to do it, potentially leading to a sedentary attitude.

Another factor to consider is the lack of financial resources (51 references), as this group does not have a large amount of money, except for those who receive scholarships or have the money provided by their families. Many of the activities they want to do require a financial investment that this group often cannot or does not want to spend, as they have other needs such as transportation or food.

Figure 2. C1.2: Reasons for abandoning leisure activities. Source: own elaboration.

4.1.3. Nearby places for leisure

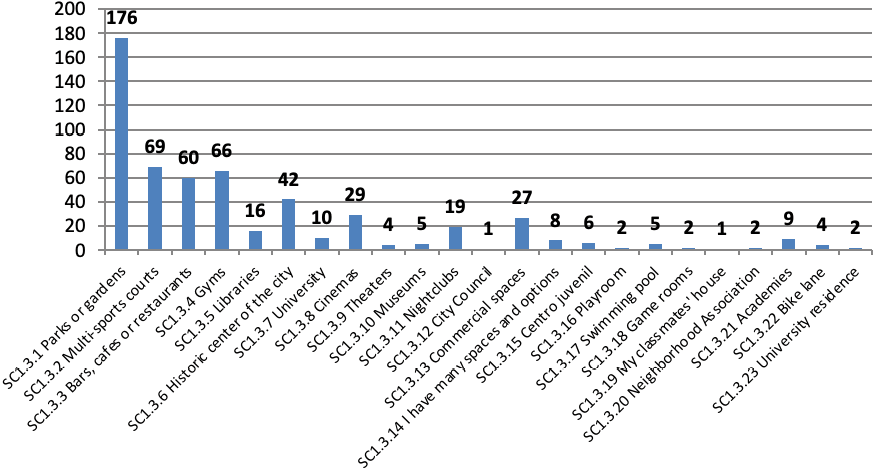

Regarding C1.3: Nearby places for leisure, the various spaces available to students within a 15-minute walk from their homes for leisure activities were analyzed. It can be observed in Figure 3 that parks and gardens (176 references) have been highlighted, where students can walk, engage in moderate physical activity such as jogging, exercises on the available bio-healthy equipment, and meet with their peers and friends in an outdoor environment.

To a lesser extent, sports courts (69 references) stand out, where different sports disciplines can be practiced, gyms (66 references), bars, cafes, or restaurants (60 references), and the historic city center (42 references). These options allow students to visit places with great cultural and architectural value, while, as students indicate, “they have all the necessary resources and are very accessible from anywhere in the city”.

4.1.4. How the pandemic has affected leisure and free time

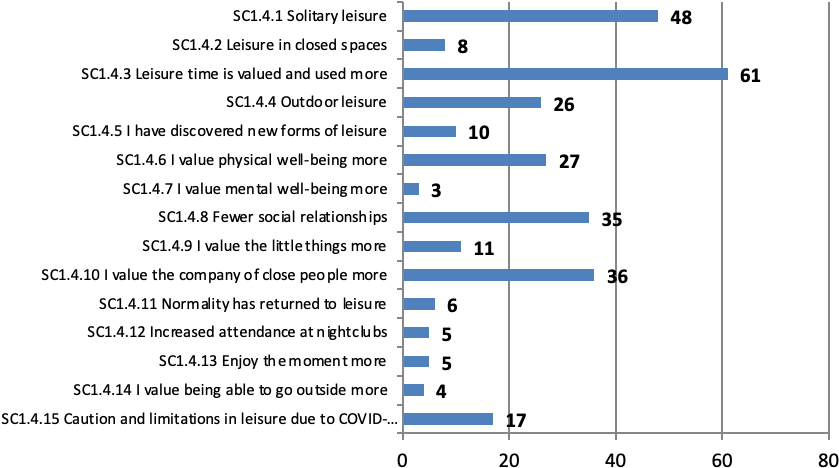

Analyzing C1.4: How the pandemic has affected leisure and free time, it can be observed in Figure 4 that students value and make more use of their leisure time (61 references), as the period of confinement at home and the reduction of their social interactions have led students to express that “I try to live more in the moment and make the most of it”, “I try to take advantage of opportunities to go out and do something”, and “I try to make the most of every moment I have because before I didn’t give it as much importance since it was always there”.

Additionally, students highlight that the pandemic has led them to engage in more leisure activities individually (48 references), with statements such as “I appreciate my time alone much more”, “I enjoy my leisure time alone more”, and “I have learned to enjoy leisure more alone”, indicating an alternative way of engaging in leisure activities without company.

On the other hand, it has been observed that students value the company of close individuals more (36 references), as reflected in statements such as “After the pandemic, I realized that I had to make the most of moments with company, so now I feel that I enjoy them more” and “I enjoy my time with friends and family more”, alongside a reduction in social interactions (35 references), as highlighted by students saying, “The pandemic has affected the way I relate to others because it has increased my fear of getting infected, and I interact with far fewer people”.

Figure 3. C1.3: Nearby places for leisure. Source: own elaboration.

Moreover, as shown in Table 2 that a significant number of references indicating unfamiliarity with the areas or activities provided by the university correspond to first-year students. This suggests that universities should focus their information channels on open days for prospective students and on the opening events of each department or faculty at the beginning of the academic year.

|

Table 2: Differences depending on the course and the subcategories linked to “lack of knowledge of areas, activities and suggestions for leisure at USAL” |

|||||

|

Subcategories |

1º |

2º |

3º |

4º |

Master |

|

SC2.1.10 I do not know the healthy leisure areas in USAL |

43.82% |

23.32% |

8.13% |

19.43% |

5.3% |

|

SC2.2.18 I do not know the healthy leisure activities of the USAL |

43.51% |

22.43% |

11.35% |

20% |

2.7% |

|

SC2.3.6 I don’t have suggestions or I don’t know what to contribute |

39.67% |

21.49% |

5.37% |

29.75% |

3.72% |

Figure 4. C1.4: How the pandemic has affected leisure and free time. Source: own elaboration.

4.2. Analysis and perception of leisure and free time at USAL

In this section, the analysis of MC2: Analysis and perception of leisure and free time at the University of Salamanca (USAL) is presented, providing a specific perspective on how leisure is addressed within the university environment. It explores the places available for leisure activities within the USAL, the leisure activities offered by the USAL, and the suggestions provided by students to improve the healthy leisure options offered by their university.

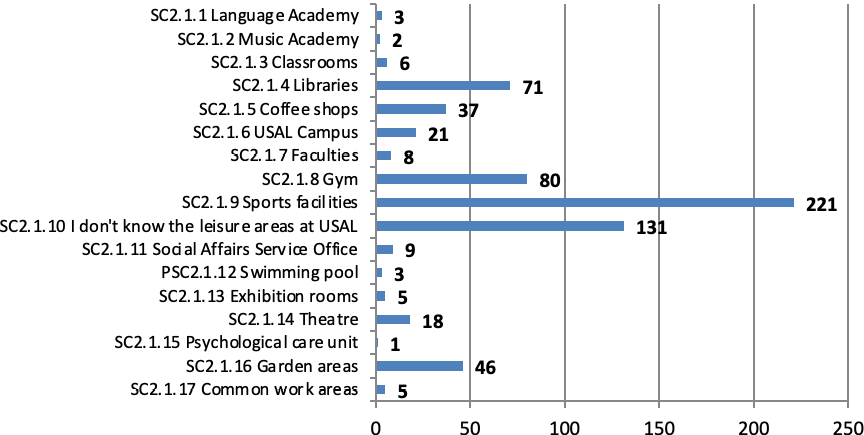

4.2.1. Available leisure spaces at the USAL

In an initial approach to C2.1: Available leisure spaces at the USAL, of which, as can be seen in Figure 5, students mainly highlight sports facilities (221 references), which include both outdoor and indoor sports infrastructure. The gym (80 references) also stands out, as well as the libraries (71 references), which gain importance within the academic context and their relevance to students, and the garden areas (46 references). However, it is worth noting that there is a high number of references indicating that students are not aware of the leisure areas at the USAL (131 references), and therefore, they will not be able to use the spaces provided for this purpose.

Figure 5. C2.1: Leisure spaces at the USAL. Source: own elaboration.

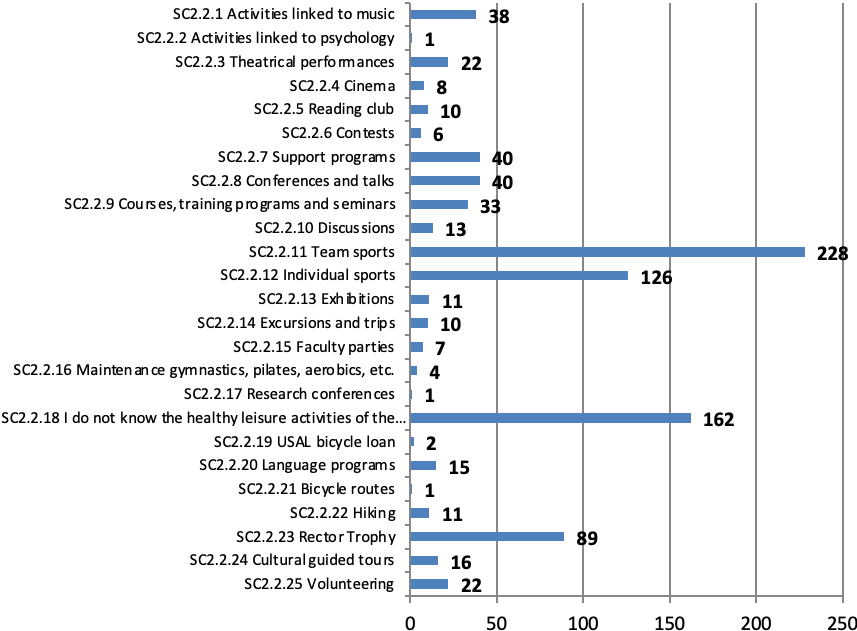

4.2.2. Healthy leisure activities offered by the USAL

Regarding C2.2: Healthy leisure activities offered by the USAL, it is noteworthy that this university offers a wide range of activities related to healthy leisure. Specifically, it has the Physical Education and Sports Service (SEFYD), responsible for promoting, organizing, and disseminating all aspects of physical and sports-related activities. As can be seen in Figure 6, students prioritize sports activities, both collective (228 references) and individual (126 references).

In Table 3, it can be observed that within collective sports, football (36.21 % of references) and basketball (27.59 % of references) stand out as the most referenced. Regarding individual sports, paddle tennis (32.5 % of references) and tennis (20 % of references) have been highlighted as the most referenced.

|

Table 3: Frequency of the most mentioned team and individual sports |

|||

|

Deporte colectivo |

Ref. (%) |

Deporte individual |

Ref. (%) |

|

Basketball |

27.59 |

Chess |

15 |

|

Handball |

2.59 |

Athletics |

7.5 |

|

Soccer |

36.21 |

Badminton |

2.5 |

|

Indoor football |

4.31 |

Climbing |

12.5 |

|

Rugby |

8.62 |

Ski |

7.5 |

|

Volleyball |

20.69 |

Swimming |

2.5 |

|

Paddle |

32.5 |

||

|

Tennis |

20 |

||

The Rector’s Trophy (89 references) has also stood out as another of the most mentioned activities by students. The Rector’s Trophy is the university’s flagship competition, pitting the various centers (faculties, schools, and residential colleges) of the University against each other in a wide variety of collective and individual sports.

However, it is worth noting that there is a high number of references indicating that students are not aware of the healthy leisure activities at USAL (162 references), with some mentions such as: “I don’t know because I am unaware of all the activities organized by USAL” or “I cannot indicate since I am not very informed”. Therefore, it is necessary to make these activities known to students, not only through traditional channels such as social media or institutional websites, as information does not seem to reach students through those channels, but also through USAL faculty themselves.

Figure 6. C2.2: Healthy leisure activities at USAL. Source: own elaboration.

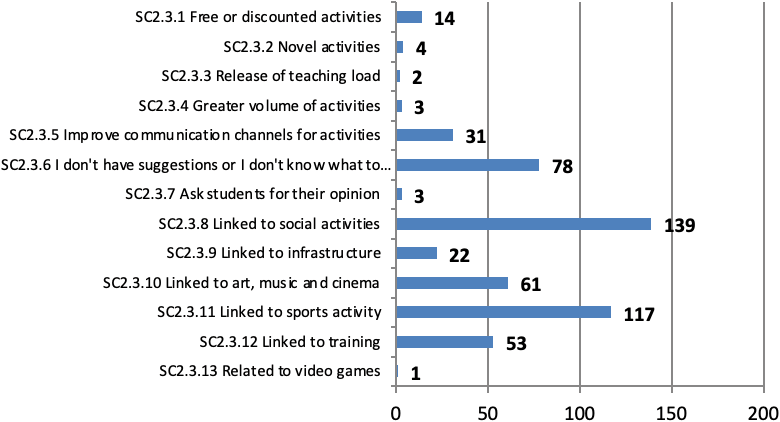

4.2.3. Suggestions to improve healthy leisure at USAL

Regarding C2.3: Suggestions to improve healthy leisure at USAL, as shown in Figure 7, the highest volume of suggestions is linked to social activities (139 references), with comments related to increased excursions, outdoor social activities, spaces for interaction with peers in a relaxed environment, faculty parties, and activities where the entire class group can interact, such as scavenger hunts or debates.

Suggestions related to sports activities were also highlighted (117 references), emphasizing the need for improvements in the gym, inclusion of more sports activities that are not solely competitive but also recreational, offering charity races to support various groups with registration proceeds, and including some activities that are not currently offered such as baseball, taekwondo, canoeing, and extreme sports. Additionally, there were a total of 78 references indicating that students have no suggestions or are unsure what to suggest, which may be related to their lack of awareness of leisure activities at USAL.

The results of this category indicate that students demand a greater variety of activities involving interaction and socialization with peers, whether in a familiar environment like USAL or an unfamiliar one outside of Salamanca, as their social interactions have noticeably decreased due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 7. C2.3: Suggestions for improving healthy leisure at USAL. Source: own elaboration.

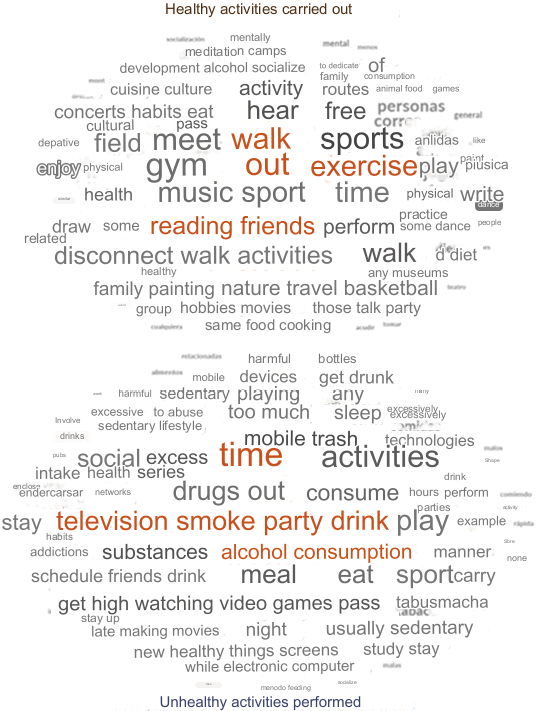

4.3. Student habits

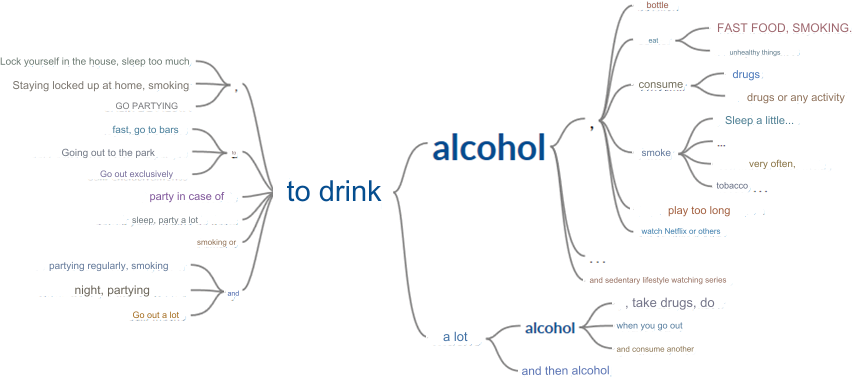

In this section, the habits of university students (MC3) are analyzed. As seen in Figure 8, sports are the most referenced (316 mentions), followed by hanging out with friends (57 mentions), walking (45 mentions), and physical exercise (39 references). Conversely, as for unhealthy habits most mentioned that influence the worsening of their quality of life, partying stands out primarily (147 mentions), followed by alcohol consumption (96 references), smoking (39 references), drugs (33 references), and inadequate and abusive consumption of fast food or pre-cooked meals (29 references).

Additionally, it has been found that alcohol exerts a significant influence on this population. This can be observed in Figure 9, illustrating how alcohol consumption is linked to sedentary behaviors, where students remain indoors without engaging in physical activity, in venues that provide alcohol, or in spaces where they engage in binge drinking. Alcohol consumption is associated with the use of other substances such as tobacco and drugs, and it is preferably consumed when partying.

Figure 8. Word clouds of healthy and unhealthy leisure activities performed. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 9. Word tree for “alcohol”. Source: own elaboration.

4.4. Gender and age differences in categories of MC1 and MC2

Regarding gender and age differences, on one hand, analyzing differences based on gender (C4.1), it can be observed from Table 4 that there are no significant differences between both groups in any of the analysis categories, as the average variance value is 1.25 %, and the variance among them ranges from 2 % in category 1.4 to 0.69 % in category 2.3. This implies that both men and women have a similar perspective on what personal leisure and leisure at USAL entail.

|

Table 4: Differences based on gender between the analysis categories |

||

|

Categories |

Hombre |

Mujer |

|

C1.1 Concept and usefulness of leisure and free time |

32.98 % |

31.55 % |

|

C1.2 Reason for giving up leisure activities |

13.39 % |

15.09 % |

|

C1.3 Nearby places for leisure |

10.1 % |

9.12 % |

|

C1.4 How the pandemic has affected leisure and free time |

11.92 % |

13.92 % |

|

C2.1 Places available for leisure at USAL |

9.05 % |

7.78 % |

|

C2.2 Healthy leisure activities offered by USAL |

9.33 % |

8.62 % |

|

C2.3 Suggestions to improve healthy leisure at USAL |

13.23 % |

13.92 % |

Regarding age differences (C4.2), some important aspects can be observed from Table 5, such as the fact that, at younger ages, there is a greater volume of references to the conceptualization and utility of leisure (C1.1: 18 years = 56.52 % compared to 29 years = 18.07 %, 30 years = 33.33 %, and 31 years = 29.03 %). This implies that these students, who often travel to a new city, have a greater consideration of what leisure means and value it more, as they invest more time in it during their first year of college than in their studies, and especially in establishing relationships and networks for their university career. Similarly, this younger student population also shows greater consideration for places near their residence to engage in leisure activities (C1.3: 18 years = 34.78 % compared to 30 years = 7.78 % and 31 years = 1.61 %), as they value and take into account those places in their immediate surroundings, as they are not familiar with other options further away, since it is their first year in the city of study.

However, this younger population gives less consideration to other aspects such as how the pandemic has affected their leisure (C1.4: 18 years = 0 % compared to 31 years = 19.35 %) compared to older students. The more mature students have shown greater consideration for the analyzed aspects such as the decrease in social relationships, loneliness, or the greater appreciation and subsequent utilization of free time, along with a lower ability to suggest improvements to USAL’s leisure offerings, compared to the younger student group (C2.3: 18 years = 0 % compared to 29 years = 31.33 %, 30 years = 21.11 %, 31 years = 16.13 %). These results confirm the differences found by course in the lack of knowledge of USAL leisure activities, as initially they are not aware of all the available offerings at USAL, and as their university career progresses, they become acquainted with the activities offered and improve their critical capacity regarding these aspects.

|

Table 5: Differences based on age between the analysis categories |

|||||||

|

Age |

C1.1 |

C1.2 |

C1.3 |

C1.4 |

C2.1 |

C2.2 |

C2.3 |

|

18 |

56.52% |

8.7% |

34.78% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

19 |

28.87% |

16.15% |

9.55% |

16.15% |

8.23% |

9.22% |

11.82% |

|

20 |

32.9% |

14.43% |

8.98% |

13.42% |

8.96% |

8.38% |

12.93% |

|

21 |

36.26% |

14.9% |

8.7% |

11.65% |

6.29% |

7.94% |

14.27% |

|

22 |

31.59% |

13.85% |

10.68% |

11.69% |

8.61% |

8.32% |

15.25% |

|

23 |

35% |

14.34% |

6.13% |

12.39% |

7.31% |

10.54% |

14.29% |

|

24 |

29.49% |

13.28% |

7.3% |

18.25% |

7.3% |

9.64% |

14.74% |

|

25 |

26.95% |

13.64% |

16.56% |

17.21% |

6.82% |

8.12% |

10.71% |

|

26 |

25.07% |

19.2% |

10.67% |

14.13% |

7.2% |

9.33% |

14.4% |

|

27 |

27.03% |

9.91% |

9.91% |

12.61% |

6.31% |

9.01% |

25.23% |

|

29 |

18.07% |

5.42% |

22.29% |

7.83% |

3.61% |

11.45% |

31.33% |

|

30 |

33.33% |

17.78% |

7.78% |

0% |

7.78% |

12.22% |

21.11% |

|

31 |

29.03% |

25.81% |

1.61% |

19.35% |

3.23% |

4.84% |

16.13% |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In response to the research questions and study objectives, it can be concluded that university students are familiar with and preferentially engage in sports activities, with team sports being more prevalent than individual sports. The Trofeo Rector stands out as a key sporting event bringing together students at USAL. These findings align with Andrés-Villas et al. (2020), who previously demonstrated in their study that sports are considered fundamental for university students, being one of their preferred choices for engaging in healthy leisure activities.

Regarding the concept of leisure and free time, it is associated with engaging in favourite activities, considered hobbies, which provide time for fun, enjoyment, entertainment, and primarily disconnection during the moments they are performed. They do not have to engage in obligatory activities and can forget about them, such as academic and domestic tasks that hinder their engagement in leisure activities. These results are in line with previous long-standing studies (Rodríguez Suárez & Agulló Tomás 1999; Sarrate Capdevila, 2008) and more recent ones (Andrés-Villas et al. 2020), which show that there have been no changes in the concept of healthy leisure over time. However, they question the results obtained by Sandoval Acuña (2017), who links the conceptualization of leisure with a negative connotation of time loss, finding in the results obtained a clear positive connotation for the participants. However, it is worth noting that a small portion of the participants fail to differentiate between the concepts of leisure and free time, implying that they may not be able to identify the utility when defining stimuli to encourage time away from their obligations, as they lack adequate structuring and understanding of the implications of these activities on their quality of life.

Regarding how university students spend their free time, the majority of participants indicated that they used to socialize with their friends until the pandemic hit. However, despite the pandemic halting leisure activities and limiting them to spending free time alone or at home, they resumed communal leisure activities after the lockdown. Nevertheless, they tend to engage in a higher volume of solitary leisure activities, as the lockdown has led them to socialize primarily through virtual spaces such as social media or online games, rather than in-person interactions. This results in fewer peer gatherings and difficulties in engaging in group sports activities. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted reflection on the time they dedicate to leisure and has helped them to value more positively the activities they engage in with their closest family members. All of this aligns with findings from other international research such as those of Woodrow & Moore (2021) and Turkmani et al. (2023).

Regarding the available spaces for healthy leisure near their residences, apart from what the University offers, they affirm that they have a wide variety of facilities and natural environments such as parks and gardens, sports courts, bars or cafes with board games, restaurants, cinemas, theatres, and shopping areas. Many of these spaces are free or low-cost, which facilitates leisure time. It is worth noting that at this stage they do not have a high level of economic availability, and most depend on family contributions and/or study grants. Both lines of results coincide with the research by Sandoval Acuña (2017).

In the in-depth analysis of the infrastructure of USAL for healthy leisure, they mention that the institution has facilities for sports practice such as a gym, athletics tracks, football fields, rugby fields, basketball courts, paddle tennis courts, tennis courts, etc. The university also offers sports linked to competitive teams that require high weekly discipline, which in many cases cannot be fulfilled due to lack of time linked to the academic workload of university life and in many cases, due to their lack of maturity to perform a good temporal structuring of the weekly activities to be carried out. They also have libraries for reading and study with flexible schedules. In addition, there are other facilities that allow students to socialize, such as landscaped areas, cafeterias, and the USAL campus itself.

As suggestions, they have highlighted those related to social factors, such as organizing activities to meet with classmates from other faculties, tourist routes, healthy parties, or gatherings in natural environments that they are unfamiliar with and include a wider range of non-competitive recreational sports activities. They demand greater dissemination and promotion of activities, especially on open days or social networks, results that coincide with those found in the study conducted by Méndez García (2010), where it is observed that students also obtain information about leisure activities through informal channels. Therefore, it is necessary to continue promoting research on improving leisure for young people, as affirmed by Agans et al. (2022) and López-Alonso et al. (2021). Additionally, it should be noted that a large part of the participants have indicated that they are unaware of the leisure areas or activities of USAL and do not have improvement proposals, which indicates a clear lack of knowledge of the university’s socio-healthy environment.

Finally, no notable differences have been found based on gender in the aspects analyzed regarding leisure and free time. However, it has been observed that with increasing age, there is a greater importance placed on knowing about activities and having a critical view of the leisure needs of young people. At the same time, it has been found that the group starting their university studies is more unaware of leisure areas and available activities, which implies that they may have more difficulty in providing improvement suggestions, may lack a comprehensive understanding of the implications of healthy and unhealthy leisure, and may end up engaging in harmful activities more easily, such as inappropriate partying or excessive consumption of alcohol, drugs, and/or tobacco, along with improper food intake and an unbalanced diet. Therefore, it is necessary to involve student associations, faculty, university centers such as Sports Services, Cultural Activities, Social Affairs, colleges, and university residences in providing counseling and support to students (Regional Health Council of Castilla y León, 2022).

Regarding the role of the University in recognizing students’ leisure practices from a pedagogical and social education perspective, the importance of adopting a comprehensive approach that recognizes leisure as a fundamental component of the educational process is emphasized. The University, through pedagogy, should promote a holistic vision of student development that includes both academic and personal growth. Additionally, from a social education perspective, the University has the responsibility to address inequalities in access to and enjoyment of leisure, promoting inclusive practices that ensure all students have the opportunity to participate in leisure activities under equitable conditions.

In terms of the practical implications of the research, the findings obtained can inform the design and implementation of programs and policies that promote a student-centered and holistic educational approach.

The main limitation found in the study was that, given the high academic workload of the students, several reminders were needed to obtain the sample. An additional limitation of the study lay in the self-reported nature of the collected data, which could have introduced biases in the responses of the participants due to the inherent subjectivity in the perception of leisure and free time. Furthermore, the sample was limited to students from the University of Salamanca, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other university contexts.

As a future line of research, the intention is to delve deeper into the leisure time consumption of university students through the use of addictive substances and malpractice, technology, social media, and video games to offer a guide of best practices (Innovation Project requested for the academic year 2023/24).

Contributions

|

Contributions |

Autores |

|

Conception and design of work |

Author 1, Author 2 |

|

Documentary search |

Author 3 |

|

Data collect |

Author 2, Author 3 |

|

Critical data analysis and interpretation |

Author 1, Author 2, Author 3 |

|

Review and approval of versions |

Author 1, Author 2, Author 3 |

Funding

This research has been funded by the Innovation and Teaching Improvement Project of the University of Salamanca for the academic year 2021/2022, entitled “Healthy Leisure for University Student Population (ID2021/172)”, and was co-funded by the European Union under the Erasmus+ program, GIRLS Project (ref. 2022-1-ES01-KA220-HED-000089166).

Conflict interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Bibliographic References

Agans, J. P., Hanna, S., Weybright, E. H., & Son, J. S. (2022). College students’ perceptions of healthy and unhealthy leisure: Associations with leisure behaviour. Leisure Studies, 41(6), 787–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2055773

Andréu, J. A. (2002). Las técnicas de análisis de contenido: una revisión actualizada. Universidad de Granada. https://www.academia.edu/download/54901527/borra.pdf

Andrés-Villas, M., Díaz-Milanés, D., Remesal-Cobreros, R., Vélez-Toral, M., & Pérez-Moreno, P. J. (2020). Dimensions of Leisure and Perceived Health in Young University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), Article 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238750

Bardin, L. (2002). El análisis de contenido. Ediciones Akal.

Caballo Villar, M. B., Caride Gómez, J. A., Gradaílle Pernas, R., Martínez García, R., & Valenzuela Bandín, Á. L. de. (2018). Investigar sobre tempos educativos e sociais. Experiencias da Rede Ociogune. Conectando redes. La relación entre la investigación y la práctica educativa. Simposio REUNI+D y RILME, 2018, ISBN 978-84-09-05212-7, pp. 531–540. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo = 7547648

Cabanillas-García, J. L., Martín-Sevillano, R., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Martín-Cilleros, M. V., Verdugo-Castro, S., Mena, J., Pinto-Llorente, A. M., & Izquierdo Álvarez, V. (2022). A Qualitative Study and Analysis on the Use, Utility, and Emotions of Technology by the Elderly in Spain. In A. P. Costa, A. Moreira, M. C. Sánchez-Gómez, & S. Wa-Mbaleka (Eds.), Computer Supported Qualitative Research. New Trends in Qualitative Research (WCQR 2022) (pp. 248–263). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04680-3_16

Chirico, I., Chattat, R., Dostálová, V., Povolná, P., Holmerová, I., de Vugt, M. E., … & Ottoboni, G. (2021). The Integration of psychosocial care into national dementia strategies across Europe: evidence from the skills in Dementia Care (SiDECar) Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073422

Consejería de Sanidad Castilla y León (2022). Guía metodológica para el desarrollo de un mapa de activos en salud orientada a profesionales de promoción de la salud. Junta de Castilla y León. https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/es/mapa-activos

Cordero Domínguez, J. D. J., & Aguilar Luna, C. (2015). Cartografiar lo cultural del ocio en el centro histórico de Guanajuato. Revista Ciudades, Estados y Política, 2(1), 15-25. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/revcep/article/view/47583

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Moreno López, L., & Sánchez-Gómez, M. C. (2018). Empirical evaluation of educational interactive systems. Quality & Quantity, 52, 2427-2434. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11135-018-0808-4

García-Toro, M., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Madrigal Zapata, L., & Lopera, F. J. (2020). “In the flesh”: Narratives of family caregivers at risk of early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 19(5), 1474-1491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218801501

Gómez-Mazorra, M., Torres, H. G. T., & Carvajal, N. I. A. (2023). Leisure and free time from a gender perspective in postgraduate university students. Retos-Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física Deporte y Recreación, 47, 823–830.

Hasanpour, S., Khakzand, M., & Faizi, M. (2023). Improving quality of leisure environment considering youth preferences in Mashhad, Iran. Frontiers in Built Environment, 8, 1066338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2022.1066338

Hemming, K., & Tillmann, F. (2023). Selective Leisure Time—Social background and the use of non-formal education in youth. Zeitschrift fur Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 43(1), 4–21.

Hernández Prados, M. Á., & Álvarez Muñoz, J. S. (2020). Una mirada socioeducativa al ocio cultural. RES. Revista de Educación Social, 31. https://eduso.net/res/revista/31/el-tema-revisiones/una-mirada-socioeducativa-al-ocio-cultural

Kinder, C. J., Nam, K., Kulinna, P. H., Woods, A. M., & McKenzie, T. L. (2023). System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth: A Systematic Review of US and Canadian Studies. Journal of School Health, 93(10), 934–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13345

Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. (1993). Building communities from the inside out. ACTA Publications.

Kono, S., Nagata, S., Dattilo, J., & Cho, S. J. (2024). Identifying leisure education topics for university student well-being: A Delphi study. Journal of Leisure Research, 55(2), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2023.2204321

Labuschagne, N., Schreck, C. M., & Weilbach, J. T. (2023). Patterns of Participation in Active Recreation and Leisure Boredom Among University Students. South African Journal for Research in Sport Physical Education and Recreation, 45(2), 46–62.

Lenze, L., Klostermann, C., Schmid, J., Lamprecht, M., & Nagel, S. (2023). The role of leisure-time physical activity in youth for lifelong activity-a latent profile analysis with retrospective life course data. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-023-00884-9

López-Alonso, A., Presa, C. L., Sánchez-Valdeón, L., López-Aguado, M., Quiñones-Pérez, M., & Fernández-Martínez, E. (2021). La universidad como un entorno saludable: Un estudio transversal. Enfermería Global, 20(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.441601

López-Cisneros, M., Sifuentes-Castro, J. A., Guzmán-Facundo, F. R., Telumbre-Terrero, J. Y., & Noh-Moo, P. M. (2021). Rasgos de personalidad y consumo de alcohol en estudiantes universitarios. SANUS, 6, e194–e194. https://doi.org/10.36789/sanus.vi1.194

Marques-Sule, E., Muñoz-Gómez, E., Almenar-Bonet, L., Moreno-Segura, N., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Deka, P., López-Vilella, R., Klompstra, L., & Cabanillas-García, J. L. (2022). Well-Being, Physical Activity, and Social Support in Octogenarians with Heart Failure during COVID-19 Confinement: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), Article 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215316

Méndez García, R. M. (2010). El tiempo libre o de ocio en la universidad: un perfil de estudiante y una responsabilidad formativa. Innovación educativa, (20), 183-202. https://minerva.usc.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10347/5007/14.Mendez.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y

Navarro-Pérez, J. J., Pérez-Cosín, J. V., & Perpiñán, S. (2015). El proceso de socialización de los adolescentes postmodernos: entre la inclusión y el riesgo. Recomendaciones para una ciudadanía sostenible. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (25), 143-170. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2015.25.07

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). (2018). El consumo nocivo de alcohol mata a más de 3 millones de personas al año, en su mayoría hombres. https://www.who.int/es/news/item/21-09-2018-harmful-use-of-alcohol-kills-more-than-3-million-people-each-year--most-of-them-men

Rodríguez Suárez, J., & Agulló Tomás, E. (1999). Estilos de vida, cultura, ocio y tiempo libre de los estudiantes universitarios. Psicothema, 11(2), 247–259. http://hdl.handle.net/10651/27674

Sánchez-Casado, L., Paredes-Carbonell, J. J., López-Sánchez, P., & Morgan, A. (2017). Mapa de activos para la salud y la convivencia: propuestas de acción desde la intersectorialidad. Index de Enfermería, 26(3), 180-184. https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script = sci_arttext&pid = S1132-12962017000200013

Sandoval Acuña, N. R. (2017). Diagnóstico acerca del uso del ocio y el tiempo libre entre los estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional Experimental del Táchira. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, (30), 169-188. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2017.30.12

Sarrate Capdevila, M. L. (2008). Ocio y tiempo libre en los centros educativos. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 60(4), 51-61. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/28868

Serrano, Á., Sanz, R., Cabanillas-García, J. L., & López-Lujan, E. (2023). Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools. Children, 10(2), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020231

Suárez, H. V., Ayán, C., Gutiérrez-Santiago, A., & Cancela, J. M. (2021). Evolución de hábitos saludables en estudiantes universitarios en ciencias del deporte. Retos, 41, 524–532. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i41.83313

Turkmani, E. M., Dzioban, K., Almasizadeh, S., Hoseinkhani, S., & Kheyri, N. (2023). Analysis of university students’ perceived freedom in leisure during covid-19 lockdowns. World Leisure Journal, 65(4), 585–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2023.2212642

Verdugo-Castro, S. (2019). Detection of needs in the lines of work of third sector entities for unemployed women in situations of social exclusion. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 0(34), Article 34. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2019.34.12

Woodrow, N., & Moore, K. (2021). The Liminal Leisure of Disadvantaged Young People in the UK Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4(5), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-021-00064-2

Woodward, T. C., Smith, M. L., Mann, M. J., Kristjansson, A., & Morehouse, H. (2023). Risk & protective factors for youth substance use across family, peers, school, & leisure domains. Children and Youth Services Review, 151, 107027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.107027

HOW TO CITE THE ARTICLE

|

Sánchez-Gómez, M.C., Cabanillas-García, J.L. & Verdugo-Castro, S. (2024). Perception and experiences of University of Salamanca students about leisure and free time. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 45, 257-280. DOI:10.7179/PSRI_2024.45.13 |

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

|

María Cruz Sánchez-Gómez. mcsago@usal.es Juan Luis Cabanillas García. jluiscabanillas@usal.es Sonia Verdugo-Castro. soniavercas@usal.es |

ACADEMIC PROFILE

|

MARÍA CRUZ SÁNCHEZ-GÓMEZ https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4726-7143 She holds a PhD and a Bachelor’s degree in Education Sciences from the University of Salamanca and a Master’s degree in Speech Therapy from the Pontifical University of Salamanca. She is a Full Professor in the Department of Teaching, Organization, and Research Methods at the University of Salamanca with a focus on Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education. Her research is applied in nature with a social component. She is a member of the Interdisciplinary Research Group on Digital Intelligence in Educational Processes (INDIE). She has developed collaborations with various research groups at IBSAL, INICO, FUNDACIÓN INTRAS, some of which are recognized for excellence by the Junta de Castilla y León (GRIAL, INFOAUTISMO), where she has contributed her expertise in research methodology, with continuous participation and leadership in international and national research projects. She has received, among others, the first National Research Award from the Caja Madrid Social Work in 2008, Honorary Mention in awards, and the Perfecta Corselas Award for educational research in 2014. JUAN LUIS CABANILLAS GARCÍA https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8458-3546 He is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Extremadura, awarded the Margarita Salas postdoctoral scholarship (2021) to carry out a research stay at the University of Salamanca with the project titled “Leisure and Free Time in the University Population”. He shares teaching duties in the Department of Teaching, Organization, and Research Methods. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Physical Education from the University of Extremadura (2009) and completed the Master’s in Research in Teacher Training and ICT (2017), receiving the award for best academic record. He has undertaken doctoral stays linked to research projects on methods and qualitative data analysis in Portugal and Honduras. He obtained his PhD in Education from UEX (2021) with the distinction of Cum Laude. He belongs to the CiberDidact research group at the Faculty of Education of the University of Extremadura and the Biomedical Research Group of Salamanca (IBSAL). He participates as a researcher in the European project: “Generation for Innovation, Resilience, Leadership and Sustainability. The game is on!”, the national project: “Design and validation of an instrument to evaluate language competence in children in Early Childhood Education (second cycle) and Primary Education (first cycle), in Castilian and Valencian. EVALCOMPLIN”, and in various teaching innovation projects at USAL. SONIA VERDUGO-CASTRO https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9357-1747 PhD with Cum Laude distinction and International Mention from the University of Salamanca (2022), with Extraordinary PhD Award from the same university (2022), and II Cecilia Castaño Award (2022). Graduated in Social Education (2016) and holding a Master’s degree in Educational Psychology (2017) from the University of Valladolid. Assistant Professor affiliated with the Department of Teaching, Organization, and Research Methods, in the area of Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education (MIDE) at the University of Salamanca. Member of the GRoup of Interaction And e-Learning (GRIAL) at the University of Salamanca, of the IUCE of USAL, and researcher at the Biomedical Research Institute of Salamanca (IBSAL). |

Notes

1. The questionnaire can be viewed at the following link: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScRPXsV_6P8kmUfPXygtWOliovxmwCeixtjip0_NhBOrd4dJQ/viewform