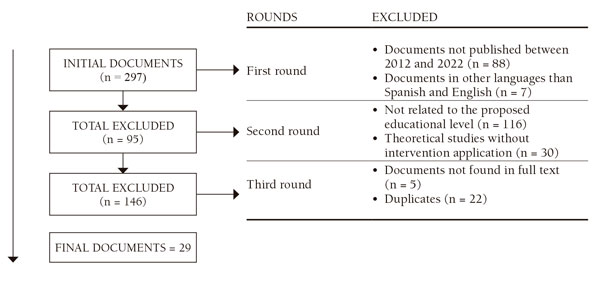

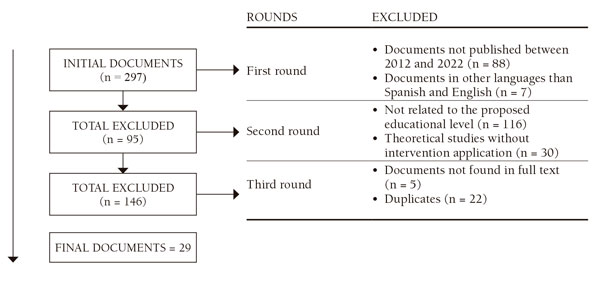

Figure 1. Flow diagram

LAURA CUERVO-CALVO(1) Y ALBERTO CABEDO-MAS(2)

(1) Universidad Complutense de Madrid (España)

(2) Universidad Jaume I de Castelló (España)

DOI: 10.13042/Bordon.2024.99887

Fecha de recepción: 17/05/2023 • Fecha de aceptación: 11/12/2023

Autora de contacto / Corresponding autor: Laura Cuervo-Calvo. E-mail: lcuervo@ucm.es

Cómo citar este artículo: Cuervo-Calvo, L. y Cabedo-Mas, A. (2024). Service-Learning and Project-Based Learning Methodologies in Higher Music Education: a review of the literature. Bordón, Revista de Pedagogía, 76(3), 35-60. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2024.99887

INTRODUCTION. Recent research highlights the potential of multidimensional and holistic learning in educational transforation, the provision of social services from the university and development of professional identity. This article aims to analyse the relationship between the Service-Learning and Project-Based Learning methodologies in higher music education and the acquisition of transversal competences. METHOD. A review of 29 articles on both methodologies in higher music education, published between 2012 and 2022, was conducted. The articles were selected from WoS, Scopus, and ERIC databases. Four categories were explored: (1) Social interaction, (2) personal growth, (3) academic learning, and (4) challenges related to the implementation and contextualization of the methodologies. RESULTS. Results show that, in the context of higher music education, both methodologies have a potentially positive impact on the development of transversal competencies in students. The review shows benefits in social aspects such as the development of civic responsibility and communication skills among peers and teachers; academic aspects such as adaptation to complex learning environments, mutually beneficial goals and shared authority; and personal development aspects such as flexibility, solidarity and respect. The review also shows that reflective practice contributes to developing students’ openness to constructive criticism, which is perceived as a positive contribution to learning. CONCLUSIONS. The methodologies studied can foster students’ personal growth, the mitigation of their biases in the classroom and the reflective and conscious appreciation of their own learning. To be taken into account are the challenges related to the complexity of adjusting the projects to the academic curriculum and community needs, as well as the large amount of time and effort required for the process. Finally, further research using different search terms and criteria is encouraged to achieve a broader understanding of how music initiatives can be designed and implemented through these methodologies, the projection they can have, and how research is conducted in this field.

Keywords: Music education, Teaching method, Service-Learning, Project Based Learning.

Education in the 21st century and Higher Music Education

The broad mission of education in 21st Century encompasses objectives such as active citizenship, personal development, and well-being (European Commission, 2012European Commission (2012). Rethinking education strategy: Investing in skills for better socio-economic outcomes. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0669&from=EN). In addition, the key for responding to social changes and the increasingly complex demands external to education is the empowerment to inclusive lifelong learning. Following Phyu and Kálmán (2023Phyu, W. & Kálmán, A. (2023). Lifelong Learning in the Educational Setting: A Systematic Literature Review. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32(2) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00738-w), students should aim to become responsible for their own learning and ‘learn learning’. They should be able to develop lifelong values and attitudes toward learning. For these purposes it is necessary that curricula deal with life skills and that education enables links between learning, life, and community. This lifelong learning prepares students to the changing information environments, as they must understand, interpret, and use scientific data; produce new ones, and have the ability to solve problems. Therefore, learning systems must be committed, among other things, to innovate and develop skills: “[…] this should start with a high standard of basic education and access at all ages to training and skills development. We also need to find new ways of learning for a society that is becoming increasingly mobile and digital as well as of providing the right blend of ‘soft’ skills, notably entrepreneurship as well as robust digital skills” (UNESCO, 2018UNESCO (2018). Council recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52018SC0014, p. 3).

In this sense, there is global awareness of the need for students to acquire a set of soft skills owing to develop the whole person. Soft skills are also known as transversal competencies and refer to issues such as ethics, attitudes, values, social-emotional and cognitive skills (Comfort & Timms, 2018Comfort, K. & Timms, M. (2018). A Twenty-First Century skills lens on the common core State standards and the next generation science standards. In E. Care, P. Griffin & M. Wilson (eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 131-145). Springer.). Recent studies provide different definitions of 21st-century transversal competencies which differ slightly from each other. UNESCO (2015UNESCO (2015). 2013 Asia-Pacific Education Research Institutes Network (ERI-Net) regional study on transversal competencies in education policy & practice..) report a core set of them in Asia-Pacific educational environments, including critical and innovative thinking, inter-personal skills, intra-personal skills and global citizenship. Another study carried on by the American Brookings institution involving a wide range of 102 world countries states that the most frequently named transversal competencies are communication, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving (Care et al., 2016Care, E., Anderson, K. & Kim. (2016). Visualizing the breadth of skills movement across education systems, Skills for a changing world. Washington, D.C. The Brookings Institution.). Underlying other recent definitions is the conception that transversal competencies cover dimensions such as human relationships, innovation, thinking skills, and technological literacy (Binkley et al., 2018Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M. & Rumble, M. (2018). Defining twenty-first century skills. In E. Care, P. Griffin & M. Wilson (eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 17-66). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2324-5_2).

With reference to human relationships, 21st Century education aims the development of self-regulated and cooperative learning (Prieto, 2008Prieto, L. (2008). Aprender entre iguales: cómo planificar una actividad de aprendizaje auténticamente cooperativa. En L. Prieto (coord.), La enseñanza universitaria centrada en el aprendizaje (pp. 117-132). Octaedro.; Torre, 2008Torre, J. C. (2008). Estrategias para potenciar la autoeficacia y la autorregulación académica. En L. Prieto (coord.), La enseñanza universitaria centrada en el aprendizaje (pp. 61-90). Octaedro. http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/143997/1/PRIETO_La-ensen%CC%83anza-universitaria-centrada-en-el-aprendizaje_p.pdf) to cope with the labor market demands that require professionals capable of working in teams and of being autonomous and self-regulated individuals (Redecker et al., 2011Redecker, Ch., Leis, M., Leendertse, M., Punie, Y., Gijsbers, G., Kirschner, P., Stoyanov, S. & Hoogveld, B. (2011). The Future of Learning: Preparing for Change. Joint Research Centre (JRC), Report of the European Commission. Luxembourg, European Union.). In case of music education, it means learning autonomously how to use musical instruments in various learning settings such as blended or distance learning (Alberich-Artal & Sangra, 2012Alberich-Artal, E. & Sangra, A. (2012). Virtual Virtuosos. A Case Study in Learning Music in Virtual Learning Environments in Spain. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 1-9. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ979597.pdf; Cruywagen & Potgieter, 2020Cruywagen, S. & Potgieter, H. (2020). The World we Live in a Perspective on Blended Learning and Music Education in Higher Education. Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 16(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.696), as well as “positive” musical group-performing, in which each student [performer] play a complementary role to the others (Bilen, 2010Bilen, S. (2010). The effect of cooperative learning on the ability of prospect of music teachers to apply Orff-Schulwerk activities. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 2, 4872-4877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.787; Campayo-Muñoz & Cabedo-Mas, 2016Campayo-Muñoz, E. & Cabedo-Mas, A. (2016). Música y competencias emocionales: posibles implicaciones para la mejora e la Educación Musical. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 13, 124-139. https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/RECIEM.51864). Moreover, it also requires approaching the proposed objectives to the acquisition of musical aptitudes using cooperative skills, maturity, reflection, and responsibility (Arriaga & Riaño, 2017Arriaga, C. & Riaño, M. E. (2017). La práctica musical desde la reflexión y la acción en la formación inicial del profesorado. ENSAYOS, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 32(1), 17-32. https://www.revista.uclm.es/index.php/ensayos).

Regarding innovation, authors agree that the University should improve learning processes and outcomes, as well as adopt teaching strategies that promote innovation (Cinque, 2016Cinque, M. (2016). “Lost in translation”. Soft skills development in European countries. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 3(2), 389-427. ; Lines, 2009Lines, D. K. (ed.) (2009). La educación musical para el nuevo milenio. Morata.). In the case of music education, some of the fundamental elements that make it possible are a playful way of learning, strong connection between theory and practice, development of creativity, promotion of autonomy, changing the role of the teacher as a guide, and fostering cooperative-peer learning (Arriaga & Riaño, 2017Arriaga, C. & Riaño, M. E. (2017). La práctica musical desde la reflexión y la acción en la formación inicial del profesorado. ENSAYOS, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 32(1), 17-32. https://www.revista.uclm.es/index.php/ensayos). In addition, evidence from research and practice reveals that the use of ICT brings innovation and transversal competences development to the process of learning, communicating, and sharing information (Gertrúdix & Gertrúdix, 2014Gertrudix, F. & Gertrudix, M. (2014). Tools and Resources for Music Creation and Consumption on WEB 2.0. Applications and Educational Possibilities. Educación XX1 17(2), 313-336. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.17.2.11493.). ICT-based learning in Music Education capitalizes on the interdependence of teaching modes, whether formal, non-formal or informal (Burnard, 2007Burnard, P. (2007). Creativity and technology: critical agents of change in the work and lives of music teachers. In: J. Finney & P. Burnard (eds.). Music Education with Digital Technology (pp.196-207). Continuum.; Cayari 2015Cayari, Ch. (2015). Participatory Culture and Informal Music Learning through Video Creation in the Curriculum. International Journal of Community Music, 8(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.8.1.41_1.), and leads to massive use of open educational resources (OER), and social media channels (Greenhow & Galvin, 2020Greenhow, Ch. & Galvin, S. (2020). Teaching with Social Media: Evidence-based Strategies for making Remote Higher Education Less Remote. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(7/8), 513-524. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0138. ; Román, 2017Román, M. (2017). Tecnología al servicio de la educación musical. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 75(268), 481-495. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP75-3-2017-09). In this sense, reinforcing critical thinking skills would enable students’ protection and effective learning (Casanova & Serrano, 2016Casanova, O. & Serrano, R. (2016) Internet, tecnología y aplicaciones para la educación musical universitaria del siglo XXI. Revista de docencia universitaria (REDU), 14(1), 405-422. https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/56660/files/texto_completo.pdf), and enhancing the digital competence would also empower learners to be more creative (Punie et al., 2014Punie, Y., Brecko, B. & Ferrari, A. (2014). DIGCOMP: A Framework for developing and understanding digital competence in Europe. eLearning Papers, 38, 5-16.). However, it should not be forgotten that musical improvisation activities in themselves already develop creative thinking (Hallam, 2010Hallam, S. (2010). The power of music: its impact on the intellectual, social, and personal development of children and young people. International Journal of Music Education, 28(3), 269-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761410370658).

On the other hand, by developing thinking skills students learn in a meaningful way and moreover, they learn to use critical thinking to find solutions as well as to be responsible for their learning (Demiral, 2018Demiral, U. (2018). Examination of critical thinking skills of preservice science teachers: A perspective of social constructivist theory. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(4), 179-190. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n4p179). In music education, there is a connection between activities that reinforce creativity and adopting critical thinking (Zhang, 2022Zhang, S. (2022). Interactive environment for music education: developing certain thinking skills in a mobile or static interactive environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(10), 6856-6868. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2049826) and fostering creative attitude in the music class may stimulate students curiosity, change their perspectives, and help them navigate both personal and social domains (Schiavio et al., 2023Schiavio, A., van der Schyff, D., Philippe, R. A. & Biasutti, M. (2023). Music teachers’ self-reported views of creativity in the context of their work. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 22(1), 60-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/14740222221125)

The shift towards twenty-first century skills is taking place in education systems, new approaches of teaching strategies are raising, and technologies are providing opportunities to more pragmatic and innovative solutions (Care, 2018Care, E. (2018). Twenty-First century skills: from theory to action. In E. Care, P. Griffin & M. Wilson (eds.) Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp.3-21). Springer.)

Teaching and Learning settings in Higher Music Education

In order to meet with the aforementioned challenges, music education has to adapt to rapidly changing societies and therefore, constantly reflect on teaching and learning processes. Schools and educational systems need to rapidly accomodate to dynamic realities and, in this, research can bring light to challenges such as connecting theory and practice, respond to social needs or promote inclusive education (Bautista et al., 2023Bautista, A., Cerdán, R., García-Carrión, R., Salsa, A. M., Aldoney, D., Cabedo-Mas, A., Campos, R., Clarà, M., Gámez-Guadix, M., Ilari, B., Kammerer, Y., Macedo-Rouet, M., Mendive, S., Múñez, D., Saux, G. I., Sun, H., Sun, J., Clara Ventura, A., Yang, W., Khalfaoui, A., Noguera, I. R., Máñez, I. & Yeung, J. (2023). What research is important today in human development, learning and education? JSED Editors’ reflections and research calls. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 46(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2022.2137980 ). The arts, and specifically, music, has a big role on these aims, and the Universities are key settings to innovate in teaching and learning processes (Clements, 2010Clements, A. (ed.) (2010). Alternative approaches in music education: Case studies from the field. R&L Education.; Walker, 2007Walker, R. (2007). Music education: Cultural values, social change and innovation. Charles C Thomas Publisher.).

Martínez-Rodríguez et al. (2018Martínez-Rodríguez J. B., Fernández-Rodríguez E. & Anguita R. (2018). Ecologías del aprendizaje: Educación expandida en contextos múltiples. Morata.) state that “arts education models must be in line with the conception of art at each moment” (p. 18) and also with learning ecologies. Music education professionals and stakeholders in higher education need to reflect on how pedagogical innovations can stimulate learning music and how different models of music making —creating, exploring, performing, etc.—– can be based on learning experiences that promote “confluence of all the contexts where learning takes place —political, cultural, social, emotional— acquiring a more social, community, participatory, reflexive, and interactive vision” (Olvera-Fernández et al., 2022Olvera-Fernández, J., Montes-Rodríguez, R. & Ocaña-Fernández, A. (2022). Innovative and disruptive pedagogies in music education: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Music Education, 41(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614221093709.)

Several methodologies and approaches in teaching and learning have been designed, implemented and assessed to test efficacy on how innovative education can serve as a way to enable more powerful, experience-based, contextualised and, in sum, better educational processes. Technology —as one, but not the only— has reformulated the methods in which people teach and learn music (Partti et al., 2021Partti, H., Weber, J. & Rolle, C. (2021). Learning a skill, or learning to learn? Supporting teachers’ professional development in music education technology. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 14(2-3), 123-139.). Among these methodologies and approaches, Project-based learning (PBL) and Service-Learning (SL) have been widely used as a way to enable leaning settings that are contextualised and emerge from real or context-based settings.

Project-based learning (PBL) is based on the idea that real-life problems can develop teaching and learning processes. This is mainly because learning based on experienced that are real or that can be connected with students’ reality have the potential to be more meaningful for them (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010Larmer, J. & Mergendoller, J. R. (2010). Seven essentials for project-based learning. Educational leadership, 68(1), 34-37.). With these principles, PBL is “a student-centred form of instruction which is built on three constructivist principles: learning is context-specific, learners are involved actively in the learning process and they achieve their goals through social interactions and the sharing of knowledge and understanding” (Kokostaki et al., 2016Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V. & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving schools, 19(3), 267-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/13654802166597). At its core, PBL can be an educational approach that enable authentic, situated and engaging learning, provoke critical thinking, and develop autonomy and creativity, by making students responsible for making choices and for designing and managing their work (Tobias et al., 2015Tobias, E. S., Campbell, M. R. & Greco, P. (2015). Bringing curriculum to life: Enacting project-based learning in music programs. Music Educators Journal, 102(2), 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/002743211560760). PBL approaches in music education has grown interest during the last years and has been proven to be an effective way of learning music and a provoking field of research (Botella-Nicolás & Ramos-Ramos, 2020Botella, A. M. & Ramos Ramos. P. (2020). El aprendizaje basado en proyectos en el aula de música. Per Musi, 40, General Topics: 1-15. e204003. https://doi.org/10.35699/2317-6377.2020.24084). As a consequence, the use of PBL initiatives in music teaching and learning has been often used in different educational settings, with multiple examples of initiatives in early childhood education (Agmaz & Ergulec, 2019Agmaz, R. F. & Ergulec, F. (2019). Music Down Here: A Project Based Learning Approach. The International Journal of Research in Teacher Education, 10(3), 42-53.), primary schools (Bylica, 2020Bylica, K. (2020) Hearing my world: negotiating borders, porosity, and relationality through cultural production in middle school music classes. Music Education Research, 22(3), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2020.1759519), secondary schools (Kibici, 2022Kibici, V. B. (2022). The effect of project-based learning approach on lesson outcomes, attitudes and retention of learned in secondary school music. OPUS-Journal of Society Research, 19(49), 771-783.), and in tertiary education, including music academies or conservatoires (Hahn, 2019Hahn, K. (2019). Inquiry into an unknown musical practice: an example of learning through project and investigation. In S. Gies & J. H. Sætre (eds.), Becoming Musicians (pp. 173-196). NMH publications.).

In a generic way, Service-Learning (SL) is a pedagogical method carried out by the reciprocal action of the students and the community, in pursuit of satisfying unmet social needs (Furco & Billig, 2002Furco, A. & Billig, S. H. (2002). Service Learning. The essence of the Pedagogy, Greenwich, CT, Information Age Publishing.; Tapia, 2008Tapia, M. N. (2008). La solidaridad como pedagogía. Ed. Criterio.). The National Society for Experiential Education, defined SL as “any carefully monitored service experience in which a student has intentional learning goals and reflects actively on what he or she is learning throughout the experience” (Furco, 1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Service Learning, General, 128. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/128). In this, the service is integrated into the curriculum, and is a means to provide students with opportunities to employ academic skills in real-life situations. The adaptation of SL approaches in education has been proven to have positive impacts on different aspects such as academic progress, self-concept and personal and social growth (White, 2001White, A. (2001). Meta-analysis of service-learning research in middle and high schools (Tesis doctoral). Denton, University of North Texas. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slcedt/67/), on the attitudes towards learning and the school, the civic commitment and the development of social skills (Celio et al., 2011Celio, C. I., Durlak, J. & Dymnicki, A. (2011). A Meta-analysis of the Impact of Service-Learning on Students, Journal of Experiential Education, 34(2), 164-181. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382591103400205) and on social and intercultural understanding (Yorio & Ye, 2012Yorio, P. L. & Ye, F. (2012). A Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Service-Learning on the Social, Personal, and Cognitive Outcomes of Learning. Academy of Management Learning &Education, 11(1), pp. 9-27. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0072).

The number of research on the personal and social effects of SL in music education settings has emerged strongly in recent times (for example, Barnes, 2002Barnes, G. V. (2002). Opportunities in service learning. Music Educators Journal, 88(4), 42-46.; Reynolds & Conway, 2003Reynolds, A. M. & Conway, C. M. (2003). Service-Learning in Music Education Methods: Perceptions of Participants. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 155, 1-10.; Reynolds et al., 2005Reynolds, A. M., Jerome, A., Preston, A. L. & Haynes, H. (2005). Service-learning in music education: Participants’ reflections. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 79-91.; Yob, 2000Yob, I. M. (2000). A feeling for others: Music education and service learning. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 8(2),67-78.). These include examples in primary education (Arrington, 2010Arrington, N. M. (2010). The effects of participating in a service-learning experience on the development of self-efficacy for self-regulated learning of third graders in an elementary school in southeastern United States (Doctoral dissertation), Clemson University, South Carolina (USA).; Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2020Chiva-Bartoll, O., Moliner, M. L. & Salvador-García, C. (2020). Can service-learning promote social well-being in primary education students? A mixed method approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 111, 104841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104841.), secondary schools (Pritchard & Whitehead, 2004Pritchard, F. F. & Whitehead, G. I. (2004). Serve and learn: Implementing and evaluating service-learning in middle and high schools. Routledge.), and in tertiary education, in which SL has been more widely used (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2019Chiva-Bartoll, O., Salvador-García, F. F. & Cabedo-Mas, A. (2019). Aprendizaje-servicio en educación musical: revisión de la literatura y recomendaciones para la práctica. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical - RECIEM, 16, 3-19.; Cuervo et al., 2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232; Gillanders et al., 2018Gillanders, C., Cores Torres, A. & Tojeiro Pérez, L. (2018). Music education and service-learning: a case study in Primary Education teacher training. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 2(42),16-30. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.42.12329). From the results reflected in these studies, it can be deduced that the contributions that the SL offers to experiences of active musical practice can be a highly desirable enhancing factor (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2019Chiva-Bartoll, O., Salvador-García, F. F. & Cabedo-Mas, A. (2019). Aprendizaje-servicio en educación musical: revisión de la literatura y recomendaciones para la práctica. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical - RECIEM, 16, 3-19.).

This study aims to analyze recent studies (2012-2022) that have applied service-learning (S-L) and project-based learning (PBL) methodologies in higher music education to understand the nature of their contributions to the acquisition of transversal competences. The study is motivated by the need to better understand approaches to educational innovation and to identify high-quality educational models that address the needs of the 21st Century.

The selected qualitative methodology is based on the research questions, and follow Miles et al. (2014Miles, M., Huberman, M. & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications.), as well as Cochrane recommendations (Higgins & Green, 2011Higgins, J. P. T. & Green S. (eds.) (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. https:// www.cochrane-handbook.org.).

The specific questions raised in this study are as follows: (1) What is the nature of the contributions of service-learning (S-L) and project-based learning (PBL) to the acquisition of transversal competences in higher music education? (2) What impacts are generated by the types of innovations provided by the studies? and (3) What challenges have emerged with the implementation and contextualization of these methodologies?

In order to answer these questions, a rigorous and objective analysis of previously selected articles was carried out (Yardley, 2017Yardley, L. (2017). Demonstrating the validity of qualitative research. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 295-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262624). The search process for the articles was carried out using the WoS, ERIC and SCOPUS databases, and inclusion and exclusion criteria such as: (1) years 2012-2022; (2) The key words were delimited as follow: Service-Learning AND music; project-based AND learning AND music, (3) English and Spanish languages were selected, (4) higher education; (5) open access only.

Regarding the selection process of the articles, from the total of the 297 articles, we reviewed the titles, abstracts and key words, with the intention of checking that they studied SL and PBL teaching methodologies and that university level in Music Education was delimited. Finally, 29 documents were selected for analysis (see Table 1 in Appendix).

Selected articles are presented in chronological and alphabetical order of authors (Table 1 in Appendix). We selectively collected data from the final articles, contrasting this material in the quest for patterns or regularities, seeking out more data to support these emerging clusters, and then gradually drawing inferences from the links between other data segments and the cumulative set of conceptualizations. This process of selecting, focusing, simplifying, abstracting, and transforming the data refers to “data condensation” and is a part of analysis that sharpens, sorts, focuses, discards, and organizes data in such a way that conclusions can be drawn and verified (Miles et al., 2014Miles, M., Huberman, M. & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications.). To address trustworthiness, we have created a matrix including authors, tittles, abstracts, key words, methods, results, and conclusions. Good data displays are a major avenue to robust qualitative analysis (Higgins & Green, 2011Higgins, J. P. T. & Green S. (eds.) (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. https:// www.cochrane-handbook.org.).

|

Figure 1. Flow diagram

|

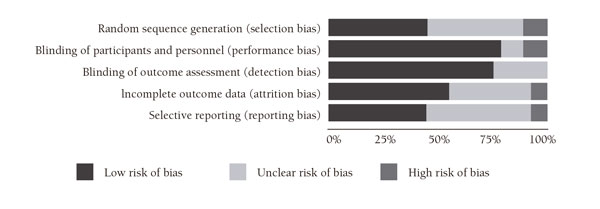

We used Cochrane 5.1.0 resource to assess for bias or systematic error in all articles included, i.e. the degree of credibility of their results. The greater the risk of bias, the less valid the conclusions about the results. We have used the Review Manager 5 (RevMan, 2020Review Manager (RevMan) (2020). [Computer program]. Version 5.4.1, The Cochrane Collaboration.) and assessed the bias domains: “selection, performance, attrition, detection and reporting” at three levels: low, high and unclear (Higgins & Green, 2011Higgins, J. P. T. & Green S. (eds.) (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. https:// www.cochrane-handbook.org., p.204). We then assessed the risk of bias between studies (see figure 2).

|

Figure 2. RevMan Risk of bias graph

|

Description of studies

Twenty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were analysed in this review (see Fig.1). Most of them were conducted in USA (16) followed by Spain (7), Australia (3), Thailand (1), Africa (1), and Chile (1). Teaching modalities included comparisons between SL and PBL approaches; synchronous online environment, multimedia and analog based learning; transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary and unique disciplines programs; peer or staff tutored session; regional and abroad experiences. Two studies involved music therapy. 23 studies were conducted with undergraduate teacher training students. Table 1 (in Appendix) provides further details about participants.

Risk of bias in studies

The differences detected in the risks of bias of individual articles may help to explain the heterogeneity of the results. The higher risk of bias in the articles refers to the non-random assignment of participants. In some studies data are lacking, which has hindered the assessment of this dimension. On the other hand, the number of participants in some studies is low (Table 1 in Appendix) and the results of studies with smaller samples are subject to greater sample variation and may therefore be less accurate.

In terms of performance, there is no evidence of bias in relation to the blinding of participants. There is no personal identification of them.

Regarding performance bias, the risk is low, since most articles mention the procedure to adequately hide the assignment sequence for the people involved in the process and for the assignment of the participating students.

The risk is also low for detection bias, that is blinging of outcomes assessment.

Finally, reporting bias resulted in an uncertain risk of bias, as not all articles reported data from the applied assessment tools, and in presenting the findings some place more emphasis on the significant results than on the non-significant ones.

On the other hand, qualitative data analysis is an iterative enterprise which connects data condensation, display, and conclusion drawing (Miles et al., 2014Miles, M., Huberman, M. & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications.). In this study, we have analysed, contrasted, and organised collected data, and have constructed patterns out of them for analytic categories (1) social interaction, (2) growth in personal attitudes, (3) academic learning, and (4) Challenges referred to the implementation and contextualization of the methodologies.

Social interaction

Preservice teacher socialization and relationship buildings are related skills to music teacher education (Forrester, 2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472). In this context, offering preservice teacher the possibility to engage in different types of authentic context learning experiences through SL programmes, expands the possibility of establishing social connections (Baughman, 2020Baughman, M. (2020). Mentorship and Learning Experiences of Preservice Teachers as Community Children’s Chorus Conductors. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(2), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719876; Gillanders et al., 2018Gillanders, C., Cores Torres, A. & Tojeiro Pérez, L. (2018). Music education and service-learning: a case study in Primary Education teacher training. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 2(42),16-30. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.42.12329) and gaining improved acceptance of one another and of the different ideas demonstrated by their peers. This attitude leads students to be aware of and celebrate the growth of others (Menard & Robert, 2014Menard, E. & Rosen, R. (2014). Preservice Music Teacher Perceptions of Mentoring Young Composers: An Exploratory Case Study. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(2), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837145526).

On the other hand, partnership characteristics of a problem-solving setting (PBL), foster communication, and valuing of each other’s contributions (Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373) as well as the ability to ask for help to get through the project (Berbel et al., 2017Berbel-Gómez, N., Jaume, M. & Rovira, M. D. P. (2017). A cooperative learning experience through life stories linked with emotions: The ‘poliedric life stories’ experience. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 1, 52-55.). By the way, working in a group, allows each student to become responsible for part of the process, and to negotiate with their peers (Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320).

Encouraging the building of relationships can be seen as a starting point for creating social change (Nichols & Sullivan, 2016Nichols, J. & Sullivan, B. M. (2016). Learning through dissonance: Critical service-learning in a juvenile detention centre as field experience in music teacher education. Research Studies in Musik Education, 18(2), 155-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X16641845). In this sense, facilitating pre-service music teacher collaborative and community connected learning might allow them to acquire understanding and dispositions to the challenges they will have to face. In the case of Cayari PBL based project (2015Cayari, Ch. (2015). Participatory Culture and Informal Music Learning through Video Creation in the Curriculum. International Journal of Community Music, 8(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.8.1.41_1.) which was developed in a virtual environment, aiming to create music videos that could be shared in class and online, students achieved increased understanding for advanced communication both in the classroom and on social media.

Moreover, community engagement SL programs in music can foster meaningful social collaborations between universities and other institutions or communities (Bartleet & Carfoot, 2013Bartleet, B.-L. & Carfoot, G. (2013). Desert Harmony: Stories of Collaboration between Indigenous Musicians and University Students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 180-196. ; Cuervo et al., 2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232), as well as some PBL programmes use to carry out multidisciplinary real-life projects (Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320; Tejada & Thayer, 2019Tejada, J. & Thayer, T. (2019). Design and validation of a music technology course for initial music teacher education based on the TPACK framework and the project-based learning approach. Journal of Music Technology and Education, 12(3), 225-246. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte_00008_1).

Thayer et al. (2021Thayer, T., Tejada, J. & Murillo, A. (2021). Technological training in secondary-school music teachers. An intervention-based study on the integration of musical, technological and pedagogical contents at the University of Valencia. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.442501) in agreement with Snow (2004Snow, K. (2004). What counts as literacy in early childhood? In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (eds.), Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development (pp. 274-294). Blackwell Publishing.), consider the community as a potentially transformative entity. The SL community music project developed by Harrop-Allin (2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695) in rural South Africa, afforded to link education with social responsibility by integrating community engagement activities into academic work. Students became more socially engaged and were aware of the benefits for both, for themselves and for the communities they served. Thus, they committed themselves to social transformation and became potential practitioners of community change. In this regard, SL experience carried out by Gubner et al. (2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ) reported similar outcomes, as engagement with community beneficiaries (people with dementia) in their careers, families, and communities continued after course completion. In the same vein, the experience developed by Parejo et al. (2021Parejo, J. L., Cortón-Heras, M. O. de la & Giraldez-Hayes, A. (2021). La dinamización musical del patio escolar: resultados de un proyecto de aprendizaje-servicio. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 18, 181-194. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1081-3529) which aimed to develop socio-cultural diversity-values by using a SL program, fostered a sense of civic responsibility towards the community in the students beyond the teaching setting. In the case of the SL experience aimed to developing musical practices shaped by the needs of a juvenile Detention Center Arts Project, the facilitated musical experience with the incarcerated youth increased pre-service music teachers’ awareness of the diversity of the sociocultural systems that shape their future students (Nichols & Sullivan, 2016Nichols, J. & Sullivan, B. M. (2016). Learning through dissonance: Critical service-learning in a juvenile detention centre as field experience in music teacher education. Research Studies in Musik Education, 18(2), 155-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X16641845). Those untraditional teaching environments were essential to examining students’ beliefs and fostering a deeper understanding of the part of the population they were working with.

An important aspect that defines community engagement is reciprocity, which in an educational context with SL or PBL programs is embodied in the development of respect, shared authority, and mutually beneficial goals (Forrester, 2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472; Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373). Moreover, music making activities with SL led to powerful learning experiences that fostered mutual appreciation (Bartleet et al., 2016Bartleet, B.-L., Sunderland, N. & Carfoot, G. (2016). Enhancing Intercultural Engagement Through Service Learning and Music Making with Indigenous Communities in Australia. Research Studies in Music Education, 38(2), 173-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X166678).

Growth in personal attitudes

Growth in personal attitudes is considered important to student preparation for life and for their professional careers (Feen-Calligan & Matthews, 2016Feen-Calligan, H. & Matthews, W. (2016). Pre-Professional Arts Based Service-Learning in Music Education and Art Therapy. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 17, 1-36. ). Self-direction and creative-leadership are some of these life and career skills (Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373). In this sense, working process of a PBL setting helps students to discover their own potential because it empowers them to be builders of their own learning and become flexible (Berrón & Monreal, 2020Berrón, E. & Monreal, I. M. (2020). Initial training of future teachers through Project Based Learning frim Music Education. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 46, 208-223. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.46.18031). In the case of Akkapram´s project (2020Akkapram, P. (2020). The impact of the Sinsai Roo Jai ton project on the development of local culture and contemporary performance in northeastern Thailand. Manusya, 23(3), 430-449), which soughed to incorporate community arts and culture as a form of cultural capital for participants through the use of PBL methodology, enabled students to courage to express their opinions in a creative way, as well as to become more discipline and patient as they step out to learn the performing arts outside of the classroom. They showed a more open attitude towards the different cultural world and its aesthetic through the collaboration with local artists, thus broadening their perception of the environment, and of the perspectives and lives of others.

On the other hand, promoting effective communication help easier manage daily situations, and leads to better collaboration (Forrester, 2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472). Learning to identify emotions from human´s voice as in the BPL setting carried out by Berbel et al. (2017Berbel-Gómez, N., Jaume, M. & Rovira, M. D. P. (2017). A cooperative learning experience through life stories linked with emotions: The ‘poliedric life stories’ experience. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 1, 52-55.), was a personal challenge that allowed to develop communication through nonverbal language, and thereafter, contributed to better understand the communications context. Yoo & Kang (2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373) reported the experiences helped preservice teachers to adapt to dynamic and complex scenarios. Although students had reported their need to create lesson plans to feel comfortable when acting as professionals, PBL made more difficult to predict each sequential step of the lesson and, therefore, helped students to develop flexibility, an open mind, and an ability to adapt to meet circumstances where crucial pedagogical skills were needed. In the end, surpassing technical, musical and pedagogical challenges (Cayari, 2015Cayari, Ch. (2015). Participatory Culture and Informal Music Learning through Video Creation in the Curriculum. International Journal of Community Music, 8(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.8.1.41_1.), led to a self-reported sense of accomplishment and satisfaction for the students.

In the case of SL environments, opportunities for personal growth occurs not only in the academic setting from teacher and peers but from beneficiary, and community. In this sense, social engagement through applied experiential SL increase student´s awareness of civic learning (Harrop-Allin, 2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695) and lead to deepen in moral values (Bartleet & Carfoot, 2013Bartleet, B.-L. & Carfoot, G. (2013). Desert Harmony: Stories of Collaboration between Indigenous Musicians and University Students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 180-196. ). Critical reflection on the social problem they are dealing with in a SL background involves emotional learning aspects which lead to a better understanding of themselves and of others. In Menard and Rosen (2014Menard, E. & Rosen, R. (2014). Preservice Music Teacher Perceptions of Mentoring Young Composers: An Exploratory Case Study. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(2), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837145526) outlined experience, undergraduate music majors participating as teacher/mentors for elementary students became aware on the importance of encouraging students without influencing their music composition ideas and they also were concern with appreciating children’s intention to gain a better understanding of them. Practising critical reflection in a SL experience develops in students the sense of receiving critical feedback as a positive learning contribution and allows professional growth. This learning is a foregone point in a collaborative setting.

Thus, SL settings contribute to develop the evolving sense of undergraduate´s identity as teacher and of their awareness of the responsibility associated with this job (Bartolome, 2017Bartolome, S. (2017). Comparing Field-Teaching Experiences: A Longitudinal Examination of Preservice and First-Year Teacher Perspectives. Journal of Research in Music Education, 65(3), 264-286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429417730043).

Academic learning

Employing PBL or SL in music teaching and learning in higher education contexts has been proven to have positive effects on academic aspects of learning. Together with leaning music —acquiring competences on music listening, composing and performing—, such methodologies can impact on different areas of students’ academic and professional development.

Akkapram (2020Akkapram, P. (2020). The impact of the Sinsai Roo Jai ton project on the development of local culture and contemporary performance in northeastern Thailand. Manusya, 23(3), 430-449) suggest that, after the experience analysed, the music students learned to work systematically after their long practice sessions and also to establish effective collaboration processes with other group of professionals. This included the ability to adjust to new behaviours, to better plan for daily work and to be able to successfully express their ideas and adapt them into the context. The study reported that some other abilities developed included responsibility and punctuality. These results are consistent with the ones addressed by Tejada & Thayer (2019Tejada, J. & Thayer, T. (2019). Design and validation of a music technology course for initial music teacher education based on the TPACK framework and the project-based learning approach. Journal of Music Technology and Education, 12(3), 225-246. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte_00008_1), and Thayer et al. (2021Thayer, T., Tejada, J. & Murillo, A. (2021). Technological training in secondary-school music teachers. An intervention-based study on the integration of musical, technological and pedagogical contents at the University of Valencia. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.442501), which identified enriching aspect of collaborative work and the exchange of opinions, mutual learning experiences, the sense of satisfaction, and the adequate focus of the course on group work. In all these cases, PBL served as a catalyst to promote reflection and critical thinking.

Together with these very aspects, SL experiences included academic achievements mainly related to the fact that students feel these processes as real versus imagined subjects and enable them to experience ideology in their own lived experience (Bartleet & Carfoot, 2013Bartleet, B.-L. & Carfoot, G. (2013). Desert Harmony: Stories of Collaboration between Indigenous Musicians and University Students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 180-196. ). In this sense, some of the articles report that employing SL strategies in the music classroom enabled to create authentic experiences that would better prepare students for their first teaching jobs (Baughman, 2020Baughman, M. (2020). Mentorship and Learning Experiences of Preservice Teachers as Community Children’s Chorus Conductors. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(2), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719876; Berrón & Monreal, 2020Berrón, E. & Monreal, I. M. (2020). Initial training of future teachers through Project Based Learning frim Music Education. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 46, 208-223. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.46.18031). This included an optimization in the strategies of social interaction and context control, and the perception of the acquired knowledge (Cuervo et al., 2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232). For preservice music teachers, participating in SL projects helped to think critically about mitigating their classroom bias and expanding their viewpoints (Harrop-Allin, 2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695; Forrester, 2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472). In this, they found their own challenges (Menard & Rosen, 2016Menard, E. & Rosen, R. (2014). Preservice Music Teacher Perceptions of Mentoring Young Composers: An Exploratory Case Study. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(2), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837145526), such as discovering their own deficiencies in error detection and choosing teaching methods on the spot Baughman (2020Baughman, M. (2020). Mentorship and Learning Experiences of Preservice Teachers as Community Children’s Chorus Conductors. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(2), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719876) reported that the students learned to manage a classroom through participating in behavior monitoring and through strategically paced rehearsals. Similarly, Koops (2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472) identified that the focus on developing the creativity of the preservice music teachers and then transferring that experience to the SL classes was one important aspect. Also, creativity was developed in PBL settings (Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373). In sum, in most studies students report that SL have the potential to make a learning experience more meaningful, and to better understand the meaning and significance of the subject (Gillanders et al., 2018Gillanders, C., Cores Torres, A. & Tojeiro Pérez, L. (2018). Music education and service-learning: a case study in Primary Education teacher training. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 2(42),16-30. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.42.12329). The same perception emerged in PBL transdisciplinary settings (Akkapram, 2022; Feen-Calligan & Matthews, 2016Feen-Calligan, H. & Matthews, W. (2016). Pre-Professional Arts Based Service-Learning in Music Education and Art Therapy. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 17, 1-36. ; Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320).

Furthermore, SL projects help to acquire different extra-musical knowledge, often related to the community which the project is developed with. Gubner et al. (2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ) research proved that music education students participating in a SL project with people with dementia pushed beyond preconceived ideas about the relationship between music and dementia. Students even reported acquiring future professional knowledge, as they became aware of the growth of an interprofessional workforce. Similarly, Bartleet & Carfoot (2013Bartleet, B.-L. & Carfoot, G. (2013). Desert Harmony: Stories of Collaboration between Indigenous Musicians and University Students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 180-196. ) reported that their students who worked with indigenous communities gained significant knowledge about the communities. Furthermore, the fact that SL projects most often work with outside communities, research show clear evidence of positive gains through reciprocity in terms of academic knowledge (Koops, 2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472). Finally, providing students with intercultural experiences through community SL programs can foster the potential to transform their understandings to other cultures (Bartleet et al., 2013Bartleet, B.-L. & Carfoot, G. (2013). Desert Harmony: Stories of Collaboration between Indigenous Musicians and University Students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 12(1), 180-196. , 2016Bartleet, B.-L., Sunderland, N. & Carfoot, G. (2016). Enhancing Intercultural Engagement Through Service Learning and Music Making with Indigenous Communities in Australia. Research Studies in Music Education, 38(2), 173-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X166678). Intercultural understanding has been also reported in PBL experiences, such as Akkapram (2020Akkapram, P. (2020). The impact of the Sinsai Roo Jai ton project on the development of local culture and contemporary performance in northeastern Thailand. Manusya, 23(3), 430-449) research findings, which suggest that working through community connections and collaborative activities with a PBL approach, enables students to achieve understanding of a different world and develops individual and collective skills to solve problems. In addition, International Service-Learning (ISL) has positive impacts on participants’ intercultural competence (Tang & Schwantes, 2021Tang, J. & Schwantes, M. (2021). International service-learning and intercultural competence of U.S. music therapists: Initial survey findings. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 30(4), 377-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2020.1841822). Such experiences between different cultural environments are nowadays encouraged through distance SL projects and online SL internships (Pike, 2017Pike, P. (2017). Improving music teaching and learning through online service: A case study of a synchronous online teaching internship. International Journal of Music Education, 35(1), 107-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415613534).

Challenges referred to the implementation and contextualization of the methodologies

According to the research, designing service-learning (S-L) projects in higher music education can pose several challenges. Firstly, working in a foreign context that may have diverse cultural backgrounds can make it difficult to develop meaningful relationships with the community and achieve mutual goals (Harrop-Allin, 2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695. This is however one strength of SL projects, as one of the challenges identified in PBL initiatives emphasize the importance of finding authentic and meaningful contexts for projects that allow for the integration of multiple skills and concepts (Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373). Finding and working with community partners is indeed enriching but requires a lot of time and effort (Gubner et al., 2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ). In some cases, Harrop-Allin (2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695) identify language barriers that can hinder effective communication. This has also been the case in some PBL initiatives (Akkapram, 2020Akkapram, P. (2020). The impact of the Sinsai Roo Jai ton project on the development of local culture and contemporary performance in northeastern Thailand. Manusya, 23(3), 430-449). Cuervo et al. (2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232) highlight the lack of clear guidelines and frameworks for designing and assessing SL initiatives in music education as a significant challenge. Other challenges include balancing the needs and expectations of multiple stakeholders, ensuring safety and health considerations for students, and determining appropriate service projects that align with the students’ learning goals and the needs of the community (Power, 2013Power, A. (2013). Developing the Music Pre-Service Teacher through International Service Learning. Australian Journal of Music Education, 2, 64-70.). Lastly, designing SL projects in a culturally appropriate way that respects cultural protocols and avoids becoming extractive or tokenistic requires ongoing communication and relationship-building with community partners, ethical considerations related to power imbalances and privilege, and ongoing critical reflection and learning by educators (Bartleet et al., 2016Bartleet, B.-L., Sunderland, N. & Carfoot, G. (2016). Enhancing Intercultural Engagement Through Service Learning and Music Making with Indigenous Communities in Australia. Research Studies in Music Education, 38(2), 173-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X166678; Parejo et al., 2021Parejo, J. L., Cortón-Heras, M. O. de la & Giraldez-Hayes, A. (2021). La dinamización musical del patio escolar: resultados de un proyecto de aprendizaje-servicio. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 18, 181-194. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1081-3529).

In relation to the curriculum, SL initiatives in music education pose several challenges related to balancing the educational and social goals of the project while maintaining high levels of musical quality. Koops (2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472) highlights the need for careful planning and collaboration between educators and community partners to align SL initiatives with music education standards and learning outcomes. Similarly, Forrester (2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472) and Cuervo et al. (2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232) note the potential tension between a focus on service and a focus on learning in SL initiatives. In addition, there is a challenge of balancing the creative and educational aspects of the project. Gubner et al. (2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ) highlight the need to create projects that are both engaging and educational for undergraduate students while producing high-quality final products that are meaningful for community partners. Power (2013Power, A. (2013). Developing the Music Pre-Service Teacher through International Service Learning. Australian Journal of Music Education, 2, 64-70.) also emphasizes the challenge of balancing the experiential learning opportunities of service with the need for academic rigor and assessment of learning outcomes.

Similarly, one of the challenges of designing PBL experiences is the development of effective project-based learning activities that address the needs of diverse learners and align with state standards (Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320). To this end, Yoo & Kang (2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373) and Berbel et al. (2017Berbel-Gómez, N., Jaume, M. & Rovira, M. D. P. (2017). A cooperative learning experience through life stories linked with emotions: The ‘poliedric life stories’ experience. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 1, 52-55.) highlight the importance of ongoing critical reflection and evaluation to improve the effectiveness of project-based learning in music education.

Forrester (2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472) and Koops (2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472) also identify challenges in relation to the time, as these initiatives may often require efforts outside of regular classroom hours and educators may often have limited time for reflection.

Both PBL and SL projects in higher music education can be also challenging due to various resource-related issues. Firstly, the lack of resources such as instruments, equipment, and access to technology can hinder the successful implementation initiatives (Harrop-Allin, 2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695). Additionally, they may require additional resources such as transportation and materials, which can create financial challenges for both educators and community partners (Koops, 2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472). To overcome these challenges, securing funding is crucial (Akkapram, 2020Akkapram, P. (2020). The impact of the Sinsai Roo Jai ton project on the development of local culture and contemporary performance in northeastern Thailand. Manusya, 23(3), 430-449; Power, 2013Power, A. (2013). Developing the Music Pre-Service Teacher through International Service Learning. Australian Journal of Music Education, 2, 64-70.).

Last, effective PAB and SL initiatives in music education require consideration of several factors related to training. Yoo & Kang (2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373) and Thayer et al. (2021Thayer, T., Tejada, J. & Murillo, A. (2021). Technological training in secondary-school music teachers. An intervention-based study on the integration of musical, technological and pedagogical contents at the University of Valencia. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.442501) note that traditional music teacher education has not always emphasized the development of 21st-century skills, which are critical for success in a rapidly evolving in different areas of PBL such as technology and industry. Due to this, there may be resistance to change among music educators and institutions, making it difficult to introduce new pedagogical approaches. Appropriate training and support for music teachers is necessary for effective implementation of SL initiatives in their classrooms (Cuervo et al., 2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232). However, some music educators may feel ill-equipped to facilitate SL initiatives due to a lack of training or experience in community engagement and service-learning, and there may be a lack of prior experience and preparation of preservice teachers (Forrester, 2019Forrester, S. H. (2019). Community Engagement in Music Education: Preservice Music Teachers’ Perceptions of an Urban Service-Learning Initiative. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719871472; Koops, 2022Koops, A. (2022). Faith, Scholarship, and Service-Learning in Music Education: A Creative Approach. Christian Higher Education, 21(1-2), 58-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2021.2004472).

Finally, both in PBL and SL initiatives, several authors identify a clear need for more research (Bartleet et al., 2016Bartleet, B.-L., Sunderland, N. & Carfoot, G. (2016). Enhancing Intercultural Engagement Through Service Learning and Music Making with Indigenous Communities in Australia. Research Studies in Music Education, 38(2), 173-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X166678; Berbel et al., 2017Berbel-Gómez, N., Jaume, M. & Rovira, M. D. P. (2017). A cooperative learning experience through life stories linked with emotions: The ‘poliedric life stories’ experience. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 1, 52-55.; Thayer et al., 2021Thayer, T., Tejada, J. & Murillo, A. (2021). Technological training in secondary-school music teachers. An intervention-based study on the integration of musical, technological and pedagogical contents at the University of Valencia. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.442501; Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320).

The aim of this study was to analyze recent studies (2012-2022) that have applied SL and PBL methodologies in higher music education to understand the nature of their contributions to the acquisition of transversal competences. We explored the categories social interaction, personal growth, academic learning, and challenges related to the implementation and contextualization of those methodologies.

With respect to social interaction, we can conclude that offering the possibility to engage in real context SL experiences increases the possibility of establishing social connections and building-up socio-cultural diversity understanding (Gubner et al., 2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ; Parejo et al., 2021Parejo, J. L., Cortón-Heras, M. O. de la & Giraldez-Hayes, A. (2021). La dinamización musical del patio escolar: resultados de un proyecto de aprendizaje-servicio. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 18, 181-194. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1081-3529). Both methodologies, SL and PBL, contribute to become more socially integrated and more willing to collaborate in academic activities (Baughman, 2020Baughman, M. (2020). Mentorship and Learning Experiences of Preservice Teachers as Community Children’s Chorus Conductors. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(2), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083719876; Gillanders et al., 2018Gillanders, C., Cores Torres, A. & Tojeiro Pérez, L. (2018). Music education and service-learning: a case study in Primary Education teacher training. Revista Electrónica de LEEME, 2(42),16-30. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.42.12329), as well as to develop respect and mutual appreciation (Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320). In this vein, these learning methodologies contributed to increase music students in higher education’s awareness and acceptance of the diversity in their class group. In the case of pre-service music teachers, these benefits may also shape their future students (Nichols & Sullivan, 2016Nichols, J. & Sullivan, B. M. (2016). Learning through dissonance: Critical service-learning in a juvenile detention centre as field experience in music teacher education. Research Studies in Musik Education, 18(2), 155-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X16641845).

In relation to personal growth, this review provides valuable insights into the contribution of those methodologies in higher music education to the acquisition of creativity, critical thinking, collaborative working, communication, and having an open attitude (Yoo & Kang, 2021Yoo, H. & Kang, S. (2021). Teaching as Improvising: Preservice Music Teacher Field Experience With 21st-Century Skills Activities. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(3), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837211021373; Thayer et al., 2021Thayer, T., Tejada, J. & Murillo, A. (2021). Technological training in secondary-school music teachers. An intervention-based study on the integration of musical, technological and pedagogical contents at the University of Valencia. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.442501; Sefton et al., 2020Sefton, T., Smith, K. & Tousignant, W. (2020). Integrating Multiliteracies for Preservice Teachers using Project-Based Learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v14i2.6320). Besides, in the case of SL environments, engagement through applied experiential learnings increases student´s awareness of civic responsibility. Learning experiences go beyond the academic context to the personal sphere and have a positive influence on students’ maturation.

Conclusions concerning academic learning suggest that both methodologies, SL and PBL contribute significantly to enable multidisciplinary learning through real projects and real settings. Moreover, they can foster collaborative work and offer the opportunity to become responsible for the own learning process.

Regarding challenges related to the implementation and contextualization of the methodologies, we can conclude that the complexity of implementation requires a serious social commitment from the teacher. Addressing Eckersley et al. (2018Eckersley, B., Tobin, K. & Windsor, S. (2018). Professional Experience and Project-Based Learning as Service Learning. In: J. Kriewaldt, A. Ambrosetti, D. Rorrison & R. Capeness (eds.), Educating Future Teachers: Innovative Perspectives in Professional Experience. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5484-6_11) results, we found out that the music teacher needs an appropriate training and support to successfully implement SL and PBL methodologies in higher music education. The challenges in implementing SL and PBL include limited resources, managing logistics, and the lack of institutional support (Harrop-Allin, 2017Harrop-Allin, S. (2017). Higher education student learning beyond the classroom: findings from a community music service-learning project in rural South Africa. Music Education Research, 19(3), 231-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1214695; Gubner et al., 2020Gubner, J., Smith, A. & Allison, T. (2020). Transforming Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Dementia through Music and Filmmaking. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(5), 1083-1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16418 ; Cuervo et al., 2021Cuervo, L, Arroyo, D., Bonastre, C. & Navarro, E. (2021). Evaluación de una intervención de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Musical, en la formación de profesorado/Evaluation of a Service-Learning Intervention in music education for teacher training. Revista Electrónica LEEME, 48, 20-38. https://doi.org/10.7203/LEEME.48.21232). By addressing these challenges, professionals in higher music education settings can develop high-quality educational models that deal with the needs of the 21st century, aimed not only at improving students’ academic skills, but also involving social skills and personal development. Teachers involved in the development of these methodologies seem to be aware of the need to implement learning beyond the curricular ones, that is, learning for life. This model aligns more with a learning process centred in the holistic development of the person, rather than only in the academic outcome.