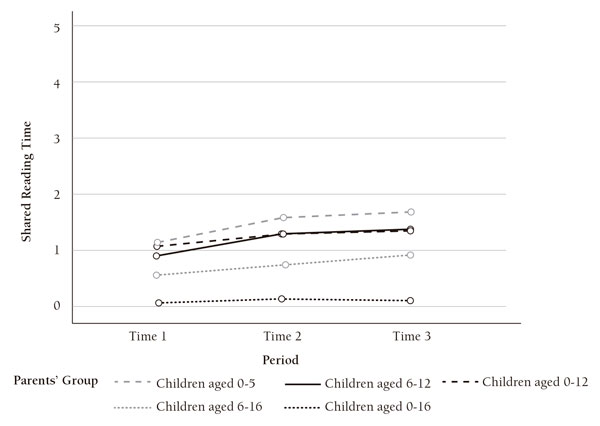

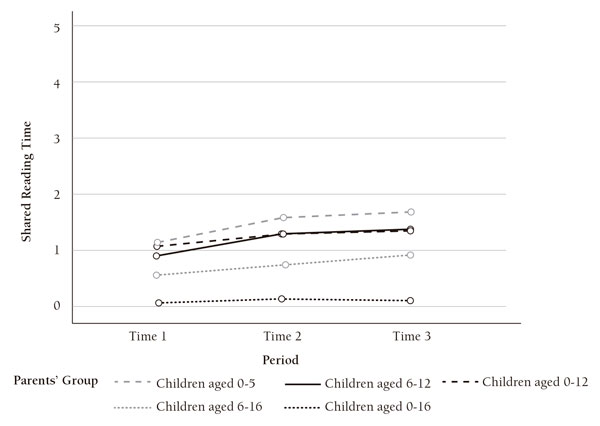

Figure 1. Interaction effect between shared reading time children’s age group

NADINA GÓMEZ-MERINO(1), ALBA RUBIO(1), VICENTA ÁVILA(1), LAURA GIL(1) AND FEDERICA NATALIZI(2)

(1) Universitat de València (Spain)

(2) Università La Sapienza di Roma (Italy)

DOI: 10.13042/Bordon.2023.94648

Fecha de recepción: 23/05/2022 • Fecha de aceptación: 27/12/2022

Autora de contacto / Corresponding author: Nadina Gómez Merino. E-mail: nadina.gomez@uv.es

Cómo citar este artículo: Gómez-Merino, N., Rubio, A., Ávila, V., Gil, L. and Natalizi, F. (2023). Effects of telework and digitalization on shared reading between parents and children. Bordón, Revista de Pedagogía, 75(1), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2023.94648

INTRODUCTION. There are several benefits associated with shared reading. The time families invest to read with their children may be influenced by different demographic (e.g., family type and structure) and personal factors (e.g., time availability). Society experiments subsequent changes and the time dedicated to shared reading at home may be influenced by them. This study has two main objectives: first, it analyzes differences in shared reading time by considering those demographic variables that other studies have identified as relevant (e.g., parents’ sex, children’s age, number of children); secondly, it aims to analyze the differences in shared reading time regarding two variables strongly affected by the pandemic, that is, the employment status and reading medium (paper reading vs. digital reading). METHOD. The responses of 659 parents to a survey about reading habits before and after confinement were analysed through a descriptive-comparative analysis of demographic variables, parents’ employment status and reading support. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION. The main results indicate that families spent increasing amounts of time on shared reading throughout confinement. In this sense, mothers spent more time reading with their children than fathers before and during confinement. Regarding the reading medium, paper continued to be used more widely for shared reading during confinement, although the time dedicated to shared reading using a digital device increased compared to its use before confinement. Finally, parents who teleworked did not invest more time on shared reading than those who worked outside the home, so that, contrary to expectations, teleworking during the pandemic did not allow for a better family-profession reconciliation or greater dedication to children’s literacy.

Keywords: Reading, Reading habits, Literacy, Teleworking, Gender, COVID-19.

The pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus has caused an accelerated change in the routines and habits of society. Among the most notable changes underscore the increasing adoption of teleworking modality (Eurofound, 2020aEurofound (2020a). COVID-19 could permanently change teleworking in Europe. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/news/news-articles/covid-19-could-permanently-change-teleworking-in-europe) and the progress towards digitalization in different areas, including education (Iivari et al., 2020Iivari, N., Sharma, S. & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life-How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183 ). In this paper, we will analyze how the changes induced by digitalization and teleworking affect children’s literacy, more specifically, the shared reading habits between parents and their children, taking into account the influence of other demographic factors.

The rapid shift from face-to-face between children and teachers to remote learning made parents assume greater responsibility for the educational progress of their children (Soriano-Ferrer et al., 2021Soriano-Ferrer, M., Morte-Soriano, M. R., Begeny, J. & Piedra-Martínez, E. (2021). Psychoeducational challenges in Spanish children with dyslexia and the parents’ stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648000 ). One of the learning tasks in which this change has been observed is reading. In fact, the way reading habits evolved during this period has been one of the focus of attention for educational researchers (Adigun et al., 2021Adigun, I. O., Oyewusi, F. O. & Aramide, K. A. (2021). The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic “Lockdown” on Reading Engagement of Selected Secondary School Students in Nigeria. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research, 3(1), 45-55. https://doi.org/10.51986/ijer-2021.vol3.01.01 , for adolescents; Salmerón et al., 2020Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 , for adults). Specifically in Spain, it was observed an increase in leisure reading time during confinement for adults (Salmerón et al., 2020Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 ) and a decrease in the percentage of readers between 7 and 13 years old (86% before, 77% meanwhile) (Federación de Gremios de Editores de España [FGEE], 2020Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (2020). El papel del libro y de la lectura durante el periodo de confinamiento por COVID-19 en España. [The role of books and reading during the period of Covid-19 confinement in Spain]. http://www.federacioneditores.org/img/documentos/confinamiento2020.pdf ).

Interestingly, while reading time decreased for primary school children (6-12 years old), younger children were more frequently exposed to shared reading with their parents or relatives (84% before, 88% during confinement). Thus, it seems that school closures during confinement brought about adjustments in family dynamics and an increase in reading time for the youngest. These changes in shared reading between parents and children associated with the COVID-19 pandemic will be the focus of this study.

According to Zucker et al. (2013Zucker, T. A., Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Pentimonti, J. M. & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). The role of frequent, interactive prekindergarten shared reading in the longitudinal development of language and literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1425-1439. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030347 ), the term shared reading involves “the interactions and discussions that occur when an adult and a child (or children) look at a book together” (p. 1). This includes sharing books with preschool children before they have started to read by themselves and reading books with older children. During early childhood, shared reading brings into play several proximal processes that help to reinforce the socio-emotional link between parents and infants (e.g., joint attention, pointing gestures, and verbal labeling) (Bus, 2001Bus, A. G. (2001). Parent-child book reading through the lens of attachment theory. In L. Verhoeven & C. E. Snow (eds.), Literacy and motivation: reading engagement in individuals and group (pp. 43-57). Routledge.). There are several benefits associated with shared reading: it boosts early vocabulary (Durkin, 1995Durkin, K. (1995). Developmental social psychology: from infancy to old age. Blackwell Publishing.), supports oral language and cognitive development (Justice & Pullen, 2003Justice, L. M. & Pullen, P. C. (2003). Promising interventions for promoting emergent literacy skills: three evidence-based approaches. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(3), 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214030230030101 ), and increases the motivation toward reading (Baker et al., 1997Baker, L., Scher, D. & Mackler, K. (1997). Home and family influences on motivations for reading. Educational Psychologist, 32(2), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3202_2 ) and academic outcomes related to reading skills or maths (Dickinson et al., 2012Dickinson, D. K., Griffith, J. A., Golinkoff, R. M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2012). How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/602807 ), which means an improvement in academic achievement (Murillo & Hernández-Castilla, 2020Murillo, F. J. & Hernández-Castilla, R. (2020). ¿La implicación de las familias influye en el rendimiento? Un estudio en educación primaria en América Latina. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 25(1), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2019.10.002 ).

Individual and family reading habits can be affected by numerous variables, including sociodemographic and cultural factors. Current evidence indicates that the time and the quality families invest may vary as a function of parents’ sex, educational level, age of children, and the number of family members (Fatonah, 2020Fatonah, N. (2020). Parental involvement in early childhood literacy development. In Proceeding International Conference on Early Childhood Education and Parenting 2009 (ECEP 2019) (pp. 193-198). Atlantis Press.). Traditionally, mothers engage in more shared reading interactions than fathers (Swain et al., 2017Swain, J., Cara, O. & Mallows, D. (2017). “We occasionally miss a bath but we never miss stories”: fathers reading to their young children in the home setting. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(2), 176-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415626635 ). However, as is well known, family structure is changing (Cutler & Palkovitz, 2020Cutler, L. & Palkovitz, R. (2020). Fathers’ shared book reading experiences: common behaviors, frequency, predictive factors, and developmental outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 56(2), 144-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2019.1683119 ) and although fathers still involve less frequently than mothers in these practices, their participation is on the rise (Cutler & Palkovitz, 2020Cutler, L. & Palkovitz, R. (2020). Fathers’ shared book reading experiences: common behaviors, frequency, predictive factors, and developmental outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 56(2), 144-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2019.1683119 ; Swain et al., 2017Swain, J., Cara, O. & Mallows, D. (2017). “We occasionally miss a bath but we never miss stories”: fathers reading to their young children in the home setting. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(2), 176-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415626635 ). Regarding the educational level, it is common to expect that families with high academic expectations would be more involved in their children’s learning than families with lower academic expectations. For example, Farrant and Zubrick (2012Farrant, B. M. & Zubrick, S. R. (2012). Early vocabulary development: the importance of joint attention and parent-child book reading. First Language, 32(3), 343-364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723711422626 ) indicate that mothers who read more frequently with their children are those with a high educational level. Another influential factor is the age of the children. The time parents tend to spend reading together with their children increases between 0-3 years old, but it decreases as their children get older (Bassok et al., 2016Bassok, D., Latham, S. & Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open, 1(4), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858415616358 ). Additionally, Bradley et al. (2001Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N. & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276-298. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276 ) observed that the percentage of adults who read to their children was higher in kindergarten (3-5 years old) than in elementary school (between 6-9 years old). Finally, regarding the number of family members, when the number of children increases from 1 to 2 or from 2 to 3, the time adults dedicate to shared reading decreases (Yarosz & Barnett, 2001Yarosz, D. J. & Barnett, W. S. (2001). Who reads to young children? Identifying predictors of family reading activities. Reading Psychology, 22(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710121153 ).

In addition to these sociodemographic and cultural factors, two additional factors of current relevance may influence the quality of shared reading: on the one hand, changes in parents’ employment and, on the other hand, the reading medium (i.e., paper vs. digital). According to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2021aInstituto Nacional de Estadística (2021a). Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH). https://www.ine.es/prensa/ech_2020.pdf), before the pandemic , in Spain, only 16% of the establishments had implemented teleworking, then it increased to 43.4% during confinement. Teleworking could allow individuals to fulfill work demands while benefiting from more flexibility, especially for certain periods, such as women during pregnancy or early childcare (Baruch, 2000Baruch, Y. (2000). Teleworking: benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 15, 34-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00063 ). However, the implementation of this modality of work during the pandemic constituted a challenge for families, who were required to find a balance between their work schedule (in case of maintaining it) and their family needs (e.g., assisting the educational needs of their children). In fact, balancing work with children’s educational support and dealing with children from different educational levels were among the greatest difficulties reported by parents when interviewed about distance learning and the pandemic (Garbe et al., 2020Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N. & Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4(3), 45-65. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471 ). On the other hand, digital devices allowed the population to continue carrying out some basic activities such as working, socializing, or studying during confinement. Moreover, several platforms and editorials allowed free access to some of their digital publications (e.g., Cervantes Institute Library, Amazon Kindle, Roca Libros, etc.). This progressive preference for digital media coupled with the greater accessibility offered by multiple platforms during confinement could have originated an emergence or increase in the habit of shared reading between parents and children with a digital support, such as ebook, tablet or notebook. According to FGEE (2021Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (2021). Hábitos de lectura y compra de libros en España. [Reading and book shopping habits in Spain]. https://www.federacioneditores.org/img/documentos/260221-notasprensa.pdf), the percentage of people (older than 14) reading in digital format increased slightly in 2020 (not only during confinement). For example, digital reading went from 29.1% to 30.3% from 2019 to 2020. Despite this slow increase and technological advances, several meta-analyses have consistently shown an advantage on reading comprehension for paper-based reading (see Delgado et al., 2018Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R. & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: a meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003 , mostly for undergraduates; Furenes et al., 2021Furenes, M. I., Kucirkova, N. & Bus, A. G. (2021). A comparison of children’s reading on paper versus screen: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(4), 483-517. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321998074 , for children from 1 to 8) and a higher preference for paper-based reading over digital-based reading. This predilection for printed documents did not change during confinement (FGEE, 2020Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (2020). El papel del libro y de la lectura durante el periodo de confinamiento por COVID-19 en España. [The role of books and reading during the period of Covid-19 confinement in Spain]. http://www.federacioneditores.org/img/documentos/confinamiento2020.pdf ). Interestingly, the way parents interact with their children during shared reading also varies as a function of the reading medium. For example, adults tend to produce more vocabulary-related clarifications when reading print books than when reading in a digital medium (Lauricella et al., 2014Lauricella, A. R., Barr, R. & Calvert, S. L. (2014). Parent-child interactions during traditional and computer storybook reading for children’s comprehension: implications for electronic storybook design. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 2(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2014.07.001 ; Munzer et al., 2019Munzer, T. G., Miller, A. L., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N. & Radesky, J. (2019). Differences in parent-toddler interactions with electronic versus print books. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20182012. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2012 ). However, they use to produce more medium-related verbalizations when reading on digital devices (Munzer et al., 2019Munzer, T. G., Miller, A. L., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N. & Radesky, J. (2019). Differences in parent-toddler interactions with electronic versus print books. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20182012. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2012 ).

Against this background, the present study aimed to describe and analyze the differences in shared reading time during the pandemic of parents with children aged 0 to 16 years old in a large sample of the Spanish population. The study is twofold: first, it analyzes differences in shared reading time by considering those demographic variables that have been reported as relevant in multiple studies (i.e., adult sex, age of the child, and the number of children at home); second, it aims to analyze differences in shared reading time by exploring two variables strongly affected by the pandemic, that is, employment status (mainly telework) and reading medium.

Given the global pandemic situation that society has experienced and the need to adapt education and work modalities to a reality not previously thought of, this study will analyze both effects with a descriptive or exploratory character.

Participants

A total of 4,181 Spaniards answered all the questions in the READ-COGvid reading habits survey (Salmerón et al., 2020Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 ), an ad hoc survey designed to evaluate reading habits during confinement (explained below). From these participants, only 828 reported having children. A total of 126 participants were excluded because they had only children over 12 years old. A total of 43 parents were also excluded due to missing data (i.e., not reporting whether they read with their children or not). The final sample consisted of 659 participants (mean age = 46.00; SD = 8.30) who had a child 0 to 12 years old, of whom 67.4% were mothers (mean age = 45.40; SD = 8.08), sex was not reported in two cases (0.2%). Regarding parents’ education, 81% of the respondents were undergraduates, while 17.6% had secondary or post-compulsory education, and 1.4% had completed primary education. As to employment status during confinement, some participants reported being unemployed (n = 115, 17.5%), whereas the rest (n = 544, 82.5%) classified their employment status into other categories: the majority of them, reported being teleworking (51.6%); whereas others were working outside the home (12%), 7.4% for temporarily suspended from work (Record of Temporary Employment Regulation [RTER]), paid leave (3.3%) or “others” (8.2%). Regarding the number of children living together at home (M = 1.67; SD = 0.64; Median = 2), half of the respondents (50.4%; n = 332) reported having two children, while the rest of the sample reported having one child (41.6%; n = 274), and only a minority reported having three children (7.3%; n = 48), or four or more (0.8%; n = 5). Among the participants, 23.8% (n = 157) reported having children who were 0 to 5 years old, 23.5% (n = 155) only children aged 6 to 12, 10.3% reported having children from both ages ranges (n = 68), 11.2% (n = 74) had children aged 6 to 12 but also children who were 12 to 16 years old; while the remaining 31.1% (n = 205) had some children (aged 0-12) and also older children (beyond 12 years old).

The study was designed following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided their consent before completing the survey. All data were recorded anonymously.

Materials and procedure

The READ-COGvid survey was designed to assess reading habits before and during confinement by Salmerón et al. (2020Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 ). Participants completed the survey in May 2020. This survey included items related to individual leisure reading habits of each parent and shared reading with children at three different periods: before confinement (Time 1); after 15 days of confinement (Time 2) and 30 days of confinement (Time 3). Other items asked for socio-demographic data (e.g., sex, children age, number of children), employment status, and reading medium (paper or digital).

Measures

The survey included the following measures:

Statistical analyzes

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (version 25). Different mean contrasts and analyses of variance were performed. Descriptive statistics are reflected in each of the analyses. Effect sizes were also calculated, specifically, partial eta squared for ANOVA and Cohen’s d.

Sex

To examine the effect of gender on the amount of shared reading time depending on the confinement period, three Student’s unpaired t-tests were carried out. We introduced period (before confinement: Time 1; after 15 days confined: Time 2; and after 30 days confined: Time 3) as a within-subjects variable, and participants’ gender as a between-subjects variable. A participant was excluded because he/she did not report gender. Table 1 shows that women tended to spend more time in shared reading together with their children in the three time periods.

| Table 1. Mean values (M), standard deviations (SD) and t-test results for shared reading time by sex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Differences in shared reading time by children’s age groups

To examine the differences in shared reading time between children’s age groups, a mixed two-way ANOVA was conducted with period as a within-subjects variable, and children’s age group as a between-subjects variable. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effects of shared reading time, χ2(2) = 76.39, p < .001, therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt for estimating sphericity (ε = .91). The results showed a significant main effect of shared reading time, F(1.82, 1188.23) = 119.22, p < .001, η2p = .154, and the age group, F(4, 654) = 108.67, p < .001, η2p = .399. Shared reading time was higher at Time 2 and Time 3 compared to Time 1 (before confinement), p < .001. The shared reading time in Time 3 was also superior to Time 2 (p < .001). Parents with children aged 0-5 spent more time reading than those with children aged 6-12 (p = .005), parents with children aged 6-16 (p < .001), and parents with children aged 0-16 (p < .001).

Figure 1 shows the significant interaction effect between shared reading time and the age group, F(7.27, 1188.23) = 17.42, p < .001, η2p = .077. Parents whose children were between 6 and 12 years of age spent more time reading with their children than those with children aged 6 to 16 years old (p < .001) or those with children from 0 to over 16 years old (p < .001). Parents with children aged 0-12 did not differ significantly from those who had children aged 0-5 (p = .359) or 6-12 (p = 1.00). Parents whose children were 6 to 16 years old spent more time reading compared to those parents with children aged 0 to over 16 years old (p < .001).

|

Figure 1. Interaction effect between shared reading time children’s age group

|

Table 2 reveals differences between time periods by age groups. For parents with children aged 0 to 5, the shared reading time was higher during confinement (Time 2 and Time 3) than before confinement (Time 1). The shared reading time after 30 days confined (Time 3) was also longer than after 15 days (Time 2). For parents with children aged 6-12 and parents with children aged 0-12 years old, the difference between the two confinement periods (Time 2 = Time 3) disappeared. For parents whose children were 6-16 years old, only Time 3 (after 30 days confined) was greater compared to Time 2 (after 15 days confined) and Time 1 (before confinement). In the remaining group (parents whose children were between 0 > 16), there was no difference in shared reading time between any period analyzed.

| Table 2. Mean values (M), standard deviations (SD), and comparison of shared reading time between three periods by the age group | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of children

To analyze the differences in shared reading time before and during confinement by number of children, a two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted with shared reading time (Time 1, Time 2 and Time 3) as a within-subjects variable, and number of children (1 to 4) as a between-subjects variable. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effects of shared reading time, χ2(2) = 101.24, p < .001, therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt for estimating sphericity (ε = .88). The results showed a significant main effect of shared reading time, F(1.76, 224.19) = 119.22, p < .001, η2p = .024, but no effect was found for the number of children or interaction.

Employment status

To analyze the differences in shared reading time before and during confinement depending on the employment status, a two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted with shared reading time as a within-subjects variable, and employment status (working outside the home, teleworking, Record of Temporary Employment Regulation [RTER], paid leave, and others) during confinement as a between-subjects variable. Some parents (N = 115) did not report their employment status during confinement, therefore, the analysis is based on the 544 adult responses. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effects of shared reading time, χ2(2) = 55.92, p < .001, therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt for estimating sphericity (ε = .92). The results showed a significant main effect of the shared reading time, F(1.84, 991.60) = 62.62, p < .001, η2p = .104, and no effect was found for employment status, F(4, 991.60) = 2.11, p = .079, η2p = .015. A significant interaction effect between shared reading time (period) and employment emerged, F(7.36, 991.60) = 4.22, p < .001, η2p = .030. The analysis of simple effects showed that parents who were working outside the home spent more time reading with their children during the confinement (Time 2 and Time 3) than before (Time 1). No differences were found between the two periods of confinement. The same trend was observed for those parents’ that reported to be teleworking during the confiment or parents whose employment status did not fit in any of the groups and were assigned to the group “others”. Parents that were temporarily suspended from work (Record of Temporary Employment Regulation [RTER]) followed a similar trend. They spent more time reading with their children during Time 2 and 3 than during Time 1, and they spent more time reading with their children during Time 3 than at Time 2 of confinement, that is, the time they devoted to reading with their children increased during confinement. Finally, no differences in shared reading time were observed between the three periods for parents whose employment status was classified in the “paid leave” group.

Shared reading medium (paper vs. digital)

To explore the preference of paper or digital medium for shared reading before and during confinement, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed with shared reading time and reading medium (paper, digital) as within-subjects variables. Only parents who reported shared reading time with their children at all three periods were included in this analysis (n = 327). Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effects of shared reading time (period), χ2(2) = 10.73, p = .005, and for the interaction between shared reading time and medium, χ2(2) = 33.51, p < .001. Therefore, degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh-Feldt estimates of sphericity (ε = .97; ε = .92 respectively). The results showed a main effect effect of the reading medium, F(1, 326) = 602.19, p < .001, η2p = .649. Thus, parents used more paper than the digital format when reading with their children. There was also a significant interaction effect between the shared reading time (period) and the reading medium, F(1.83, 596.98) = 45.66, p < .001, η2p = .123. Paper was used more in Time 1, that is, before confinement (F(1, 326) = 959.67, p < .001, η2p = .746) compared to Time 2 (F(1, 326) = 403.17, p < .001, η2p = .553) or Time 3 (F(1, 326) = 327.14, p < .001, η2p = .501), and there were no significant differences between Time 2 and Time 3 (p = .077). Table 4 shows that the use of digital medium increased during the pandemic compared to before confinement (p < .001), and there were no significant differences during confinement (Time 2 vs. Time 3, p = .458). The superiority of paper over digital medium for shared reading was present even before confinement and persisted after 15 and 30 days confined (Time 1-3; p < .001).

| Table 3. Mean values (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the shared reading time between three periods by employment status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Table 4. Mean values (M), standard deviations (SD) and ANOVAs’ results for shared reading time by reading medium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The present study aimed to describe and analyze the differences in shared reading time between parents and children during the pandemic.

First, we analyzed how several demographic variables influenced the time dedicated to shared reading. Consistent with the traditional trend (Swain et al., 2017Swain, J., Cara, O. & Mallows, D. (2017). “We occasionally miss a bath but we never miss stories”: fathers reading to their young children in the home setting. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(2), 176-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415626635 ), results revealed that mothers engaged more frequently than fathers in these practices before and during confinement. Traditionally, the mother had the role of caring for and educating her children because she did not work outside the home; but nowadays more and more women are working in the paid world of work, making it necessary to have parental co-responsibility in literacy habits or at least in shared reading time with the children. However, most of the respondents were mothers, and therefore, results should be cautiously interpreted. Our findings should raise awareness of the inequalities regarding gender parental sex roles and encourage fathers to participate in shared reading practices at home.

Further interesting results are related to the differences in shared reading time across children’s ages. In line with previous studies (Bradley et al., 2001Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N. & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276-298. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276 ), parents spent more time reading with their children when they attended Preschool than when they attended higher grades (either before or during confinement). This is an expected result as children aged 0 to 6 have limited ability to read independently and depend on adults to access books through read-aloud (Bao et al., 2020Bao, X., Qu, H., Zhang, R. & Hogan, T. P. (2020). Literacy loss in kindergarten children during COVID-19 School Closures. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/nbv79). Moreover, for those parents with children aged 0-5, the time spent reading with them increased as confinement went on, which might have helped to compensate for the reading loss that would result from school closures (Bao et al., 2020Bao, X., Qu, H., Zhang, R. & Hogan, T. P. (2020). Literacy loss in kindergarten children during COVID-19 School Closures. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/nbv79). The trend was different when at least one child attended Primary School (6-12 years old). In these cases, shared reading time increased during confinement in comparison to before the pandemic. However, the time they spent on these practices remained constant throughout lockdown (after 15 or 30 days in confinement). One possible explanation is that parents may have considered shared reading time as an activity embedded in most students’ academic routines (for example, reading the textbook to prepare an exam or doing homework) and not as a simple act of sharing a reading experience with their children. This explanation would also hold for the results from parents with at least one child attending Secondary education (13-16 years old). In this latter case, differences only emerged after 30 days of lockdown. That is, students of that age are more autonomous when doing homework, but parents’ involvement may increase as they approach exams (maybe when they were 30 days confined, assessments were more frequent than at the beginning). It may also have occurred that older students supported their younger siblings during literacy development. All in all, our results reflect the effort parents made to support the educational development of their children during these times (Soriano-Ferrer et al., 2021Soriano-Ferrer, M., Morte-Soriano, M. R., Begeny, J. & Piedra-Martínez, E. (2021). Psychoeducational challenges in Spanish children with dyslexia and the parents’ stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648000 ).

According to previous literature, the number of children at home influences the frequency of shared reading, decreasing as the number of children increases from 1 to 2 and from 2 to 3 (Yarosz & Barnett, 2001Yarosz, D. J. & Barnett, W. S. (2001). Who reads to young children? Identifying predictors of family reading activities. Reading Psychology, 22(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710121153 ). When this happens, the person responsible for the care and education of the children must spend the same amount of free and leisure time among more members of the family. In this particular scenario, it could be expected that the increase in educational responsibilities, together with the difficulty of conciliating family and professional life, resulted in a reduction of the time dedicated to shared reading as the number of children living at home increased. However, our results did not support this statement. This discrepancy could be explained by the size of our sample. Over 7,000 participants took part in Yarosz and Barnett’s study whereas our sample was composed of data from 659 respondents. In the present study, half of the sample (50%) reported having two children at home, while almost the other half (41.9%) reported living with only one child. Only a small percentage of the sample reported living with at least 3 children (less than 10%). This distribution appears similar to the study by Yarosz and Barnett, where the majority (43.5%) reported living with two children, 31.2% of the sample reported having one child and a smaller percentage (25%) reported having three or more children. Furthermore, our sample fairly represents the typical distribution of the Spanish population, since the typical number of children ranges between 1 and 2 (INE, 2021bInstituto Nacional de Estadística (2021b). Indicadores de confianza empresarial. Módulo sobre el impacto del COVID-19. https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/COVID/ice/2020/p02/l0/&file=01010.px ).

The second goal aimed to explore how teleworking and reading medium affect parent-child reading practices. Regarding the status of employment, an interesting and unexpected result was that parents who teleworked did not spend more time reading with their children than those who worked outside their homes. One of the conceived advantages of teleworking is its flexibility. However, teleworking during the pandemic did not help the population to find a better work-family balance. In fact, some data from a previous study suggest that parents might have devoted more time to work. For example, according to Salmerón et al. (2020Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 ), the time dedicated to working reading increased throughout confinement, whereas the time dedicated to leisure reading did not. Therefore, telework did not appear as profitable as we expected. We should consider that the results could have been different if telework and assessments had been implemented not occasionally but in the long term. Eurofound (2020bEurofound (2020b). Telework and ICT-based mobile work: flexible working in the digital age. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/telework-and-ict-based-mobile-work-flexible-working-in-the-digital-age) demonstrated that when telework was occasional, families reported difficulties in finding a family-work-life balance. In contrast, when telework was implemented as part of their routine (regularly) families benefited from it. Therefore, our results could be related to a forced and unsuccessful implementation of telework. For example, people might not have had the technological resources needed to telework efficiently. Indeed, some parents had to share their personal laptop with their children to complete work and scholar duties (Blahopoulou et al., 2022Blahopoulou, J., Ortiz-Bonnin, S., Montañez-Juan, M. et al. (2022). Telework satisfaction, wellbeing and performance in the digital era. Lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Current Psychology, 41, 2507-2520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02873-x ), having to stablish “turns” to work with the computer could have reduced the possibility of spending some time together in other activities.

Finally, in terms of shared reading medium, our results were in line with previous studies reporting that when reading with/to their children, adults choose paper over digital reading (Kucirkova & Littleton, 2016Kucirkova, N. & Littleton, K. (2016) The digital reading habits of children: a national survey of parents’ perceptions of and practices in relation to children’s reading for pleasure with print and digital books. http://www.book trust.org.uk/news-andblogs/news/137). The growing digitalization has not been reflected in the habit of shared reading between parents and children, even though there are digital platforms with promotions and free ebooks. The fact that some parents prefer to limit screen time to their children may be one of the reasons for this preference (Kucirkova & Littleton, 2016Kucirkova, N. & Littleton, K. (2016) The digital reading habits of children: a national survey of parents’ perceptions of and practices in relation to children’s reading for pleasure with print and digital books. http://www.book trust.org.uk/news-andblogs/news/137). Additionally, as noted in previous studies, the quality of reading may decrease when using digital devices (Delgado et al., 2018Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R. & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: a meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003 ; Furenes et al., 2021Furenes, M. I., Kucirkova, N. & Bus, A. G. (2021). A comparison of children’s reading on paper versus screen: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(4), 483-517. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321998074 ). Confinement seems to have accelerated the adoption of digital reading habits. As we have observed, the use of digital devices for shared reading increased along with confinement. Therefore, our data call designers to control multimedia aspects that can enhance but not distract shared reading experiences.

Limitations

This study is not exempt from limitations. The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and for future research:

First, the nature of the study (ex post facto, non-experimental) implies no generalization of the results but can offer an interesting point of view of the shared reading practices in a family context. Furthermore, participants may have misinterpreted the term “shared reading” by associating it with their participation in the completion of homework assignments. Although some data suggest that the interpretation was correct (e.g., more time for children aged 0 to 6), it would be necessary to clarify the term in future studies. Second, all measures were based on parental reports, so their responses could be biased by social desirability by reporting more shared reading time than actually doing. Third, participants were asked to report their shared reading time during a specific week. Reading in a particular week might vary for several reasons (e.g., illness, vacation). We do not seek to explain this variation. Fourth, collecting data after the pandemic would complement our results and provide long-term evidence of the variables analyzed. Finally, most of the surveyed families are highly educated (81%) and were teleworking (51.6%). This is a common limitation from similar studies (see Marjanovič-Umek et al., 2019Marjanovič-Umek, L., Hacin, K. & Fekonja, U. (2019). The quality of mother-child shared reading: its relations to child’s storytelling and home literacy environment. Early Child Development and Care, 189(7), 1135-1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1369975 ). Therefore, our results could be different for parents with a lower educational level or parents with less economic and digital resources to carry out shared reading with their children. Future studies should consider including a less specific sample, and they should gather responses from both parents (mother and father).

During the pandemic, mothers continued to be more involved in shared reading with their children. Reading time increased progressively when children only attended Preschool grades. In contrast, for families with children from latter educational stages, the increase may reflect the need to assume educational and instructional responsibility due to the school closures. Moreover, teleworking did not lead to better reconciliation and dedication to children’s literacy. Finally, the reading medium of choice is still paper, however, its use decreased during confinement in favor of the digital medium. The forced change of digitalization during the lockdown could be one possible explanation for this. Further studies should be conducted to confirm this statement.

Despite its predictability, the results found here may be of interest to the educational community, especially for coeducation and coordination between families and schools. Teachers should encourage shared reading time at home by mothers, but also by fathers. Likewise, teachers should take into account that the number of children influences the time and the possibility of leisure reading between parents and children, beyond homework time, which increases progressively with age. This aspect should also be considered by the educational community, since the time a child dedicates to homework takes away from pleasant reading and, consequently, from the possibility of generating a reading habit of his or her own free will. Finally, it is advisable to offer reading materials in paper format, because of their more manipulative nature and because their processing is more active according to recent studies (Delgado et al., 2018Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R. & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: a meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003 ; Furenes et al., 2021Furenes, M. I., Kucirkova, N. & Bus, A. G. (2021). A comparison of children’s reading on paper versus screen: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(4), 483-517. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321998074 ).

Nadina Gómez-Merino was contracted with fundings from the University of Valencia (Grant reference UV-INV- PREDOC17F1-540538-POP) and is currently contracted with fundings from the Ministry of Universities of the Government of Spain (UV-EXPSOLP2U- 1807959 / MS21-063). Alba Rubio was contracted with fundings from the Ministry of Universities of the Government of Spain (FPU15/02280), followed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Education (CPI-21-041), and is currently contracted at Florida Universitaria (Valencia) as a Professor Doctor. We would like to thank the rest of the project team (Barbara Arfé, Raquel Cerdán, Raquel de Sixte, Pablo Delgado, Inmaculada Fajardo, Antonio Ferrer, María García, Álvaro Jáñez, Gemma Lluch, Amelia Mañá, Lucía Mason, Manuel Perea, Marina Pi-Ruano, Luis Ramos, Marta Ramos, Javier Roca, Eva Rosa, Javier Rosales, Ladislao Salmerón, Marian Serrano-Mendizábal, Noemi Skrobiszewska, Cristina Vargas and Marta Vergara) and the people who completed the READ-COGvid survey.

| ○ | Adigun, I. O., Oyewusi, F. O. & Aramide, K. A. (2021). The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic “Lockdown” on Reading Engagement of Selected Secondary School Students in Nigeria. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research, 3(1), 45-55. https://doi.org/10.51986/ijer-2021.vol3.01.01 |

| ○ | Baker, L., Scher, D. & Mackler, K. (1997). Home and family influences on motivations for reading. Educational Psychologist, 32(2), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3202_2 |

| ○ | Bao, X., Qu, H., Zhang, R. & Hogan, T. P. (2020). Literacy loss in kindergarten children during COVID-19 School Closures. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/nbv79 |

| ○ | Baruch, Y. (2000). Teleworking: benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 15, 34-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00063 |

| ○ | Bassok, D., Latham, S. & Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open, 1(4), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858415616358 |

| ○ | Blahopoulou, J., Ortiz-Bonnin, S., Montañez-Juan, M. et al. (2022). Telework satisfaction, wellbeing and performance in the digital era. Lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Current Psychology, 41, 2507-2520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02873-x |

| ○ | Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N. & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276-298. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276 |

| ○ | Bus, A. G. (2001). Parent-child book reading through the lens of attachment theory. In L. Verhoeven & C. E. Snow (eds.), Literacy and motivation: reading engagement in individuals and group (pp. 43-57). Routledge. |

| ○ | Cutler, L. & Palkovitz, R. (2020). Fathers’ shared book reading experiences: common behaviors, frequency, predictive factors, and developmental outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 56(2), 144-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2019.1683119 |

| ○ | Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R. & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: a meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003 |

| ○ | Dickinson, D. K., Griffith, J. A., Golinkoff, R. M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2012). How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/602807 |

| ○ | Durkin, K. (1995). Developmental social psychology: from infancy to old age. Blackwell Publishing. |

| ○ | Eurofound (2020a). COVID-19 could permanently change teleworking in Europe. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/news/news-articles/covid-19-could-permanently-change-teleworking-in-europe |

| ○ | Eurofound (2020b). Telework and ICT-based mobile work: flexible working in the digital age. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/telework-and-ict-based-mobile-work-flexible-working-in-the-digital-age |

| ○ | Farrant, B. M. & Zubrick, S. R. (2012). Early vocabulary development: the importance of joint attention and parent-child book reading. First Language, 32(3), 343-364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723711422626 |

| ○ | Fatonah, N. (2020). Parental involvement in early childhood literacy development. In Proceeding International Conference on Early Childhood Education and Parenting 2009 (ECEP 2019) (pp. 193-198). Atlantis Press. |

| ○ | Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (2020). El papel del libro y de la lectura durante el periodo de confinamiento por COVID-19 en España. [The role of books and reading during the period of Covid-19 confinement in Spain]. http://www.federacioneditores.org/img/documentos/confinamiento2020.pdf |

| ○ | Federación de Gremios de Editores de España (2021). Hábitos de lectura y compra de libros en España. [Reading and book shopping habits in Spain]. https://www.federacioneditores.org/img/documentos/260221-notasprensa.pdf |

| ○ | Furenes, M. I., Kucirkova, N. & Bus, A. G. (2021). A comparison of children’s reading on paper versus screen: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(4), 483-517. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654321998074 |

| ○ | Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N. & Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4(3), 45-65. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471 |

| ○ | Iivari, N., Sharma, S. & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life-How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183 |

| ○ | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2021a). Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH). https://www.ine.es/prensa/ech_2020.pdf |

| ○ | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2021b). Indicadores de confianza empresarial. Módulo sobre el impacto del COVID-19. https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/COVID/ice/2020/p02/l0/&file=01010.px |

| ○ | Justice, L. M. & Pullen, P. C. (2003). Promising interventions for promoting emergent literacy skills: three evidence-based approaches. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(3), 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214030230030101 |

| ○ | Kucirkova, N. & Littleton, K. (2016) The digital reading habits of children: a national survey of parents’ perceptions of and practices in relation to children’s reading for pleasure with print and digital books. http://www.booktrust.org.uk/news-andblogs/news/137 |

| ○ | Lauricella, A. R., Barr, R. & Calvert, S. L. (2014). Parent-child interactions during traditional and computer storybook reading for children’s comprehension: implications for electronic storybook design. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 2(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2014.07.001 |

| ○ | Marjanovič-Umek, L., Hacin, K. & Fekonja, U. (2019). The quality of mother-child shared reading: its relations to child’s storytelling and home literacy environment. Early Child Development and Care, 189(7), 1135-1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1369975 |

| ○ | Munzer, T. G., Miller, A. L., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N. & Radesky, J. (2019). Differences in parent-toddler interactions with electronic versus print books. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20182012. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2012 |

| ○ | Murillo, F. J. & Hernández-Castilla, R. (2020). ¿La implicación de las familias influye en el rendimiento? Un estudio en educación primaria en América Latina. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 25(1), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2019.10.002 |

| ○ | Salmerón, L., Arfé, B., Ávila, V., Cerdán, R., De Sixte, R., Delgado, P. et al. (2020). READ-COGvid: a database from reading and media habits during COVID-19 confinement in Spain and Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575241 |

| ○ | Soriano-Ferrer, M., Morte-Soriano, M. R., Begeny, J. & Piedra-Martínez, E. (2021). Psychoeducational challenges in Spanish children with dyslexia and the parents’ stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2005. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648000 |

| ○ | Swain, J., Cara, O. & Mallows, D. (2017). “We occasionally miss a bath but we never miss stories”: fathers reading to their young children in the home setting. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(2), 176-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415626635 |

| ○ | Yarosz, D. J. & Barnett, W. S. (2001). Who reads to young children? Identifying predictors of family reading activities. Reading Psychology, 22(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710121153 |

| ○ | Zucker, T. A., Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Pentimonti, J. M. & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). The role of frequent, interactive prekindergarten shared reading in the longitudinal development of language and literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1425-1439. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030347 |

Efectos del teletrabajo y la digitalización en la lectura compartida entre padres e hijos

OBJETIVO. Existen diversos beneficios asociados a la lectura compartida. El tiempo que las familias dedican a leer con sus hijos puede estar influenciado por diferentes factores demográficos (p. ej., tipo y estructura familiar) y personales (p. ej., disponibilidad de tiempo). La sociedad experimenta sucesivos cambios y el tiempo dedicado a la lectura compartida en el hogar puede verse influenciado por los mismos. Este estudio tiene dos objetivos: en primer lugar, analizar las diferencias en el tiempo de lectura compartida considerando aquellas variables demográficas que otros estudios han identificado como relevantes (sexo del progenitor, edad de los hijos, número de hijos); en segundo lugar, examinar las diferencias en el tiempo de lectura compartida atendiendo a dos variables fuertemente afectadas por la pandemia: la situación laboral y el soporte de lectura (lectura en papel vs. lectura digital). MÉTODO. A través de un análisis comparativo-descriptivo de variables demográficas, situación laboral y soporte de lectura se analizaron las respuestas de 659 padres a una encuesta sobre hábitos lectores antes y después del confinamiento. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN. Los resultados principales indican que las familias dedican cada vez mayor tiempo a la lectura compartida a lo largo del confinamiento. En este sentido, las madres invirtieron más tiempo que los padres tanto antes como durante el confinamiento. Atendiendo al soporte, el papel continuó siendo más utilizado para la lectura compartida durante el confinamiento, aunque el tiempo dedicado a la lectura compartida mediante soporte digital aumentó en comparación con su uso anterior al confinamiento. Finalmente, los padres que teletrabajaron no invirtieron más tiempo de lectura compartida que aquellos que trabajaban fuera del hogar, por lo que contrariamente a lo esperado, el teletrabajo durante la pandemia tampoco permitió una mejor conciliación familia-profesión ni una mayor dedicación a la alfabetización de los niños.

Palabras clave: Lectura, Hábitos lectores, Literatura, Teletrabajo, Género, COVID-19.

Effets du télétravail et de la numérisation sur la lecture partagée entre parents et enfants

OBJECTIF. La lecture partagée présente un certain nombre d’avantages. Le temps que les familles passent à lire avec leurs enfants peut être influencé par différents facteurs démographiques (par exemple, le type et la structure de la famille) et personnels (par exemple, le temps disponible). La société subit des changements successifs et le temps consacré à la lecture partagée à la maison peut être influencé par ces changements. Cette étude a deux objectifs : premièrement, analyser les différences dans le temps de lecture partagée en tenant compte des variables démographiques que d’autres études ont identifiées comme pertinentes (sexe du parent, âge des enfants, nombre d’enfants) ; deuxièmement, examiner les différences dans le temps de lecture partagée en tenant compte de deux variables fortement affectées par la pandémie : le statut professionnel et le support de lecture (papier vs. numérique). MÉTHODE. Par le biais d’une analyse comparative-descriptive des variables démographiques, du statut professionnel et du soutien à la lecture, les réponses de 659 parents à une enquête sur les habitudes de lecture avant et après le confinement ont été analysées. RÉSULTATS ET DISCUSSION. Les principaux résultats indiquent que les familles consacrent de plus en plus de temps à la lecture partagée tout au long du confinement. En ce sens, les mères ont passé plus de temps que les pères avant et pendant le confinement. En ce qui concerne le support, pendant le confinement le papier a continué à être plus largement utilisé pour la lecture partagée, bien que le temps consacré à la lecture partagée via les médias numériques ait augmenté par rapport à son utilisation avant le confinement. Enfin, les parents qui ont télétravaillé n’ont pas consacré plus de temps à la lecture partagée que ceux qui travaillaient à l’extérieur de la maison, de sorte que, contrairement aux attentes, le télétravail pendant la pandémie n’a pas permis un meilleur équilibre travail-famille ou un plus grand engagement envers l’alphabétisation des enfants.

Mots-clés: Lecture, Habitudes de lecture, Littérature, Télétravail, Genre, COVID-19.

Nadina Gómez-Merino (corresponding author)

PhD, member of the Reading Research Unit from the University of Valencia. Postdoctoral researcher, recipient of the Margarita Salas grant. Her research has focused on the typical and atypical development of language and literacy skills in population with special educational needs (mainly population with deafness and autism spectrum disorder).

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9234-406X

E-mail: nadina.gomez@uv.es

Correspondence address: Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación, Av. Blasco Ibáñez, 21, 46010 Valencia, España.

Alba Rubio

PhD with international doctorate mention, University of Valencia. Her research is related to reading competence and comprehension, assessment, and the development of learning activities from written texts. She works as a researcher and teacher at the Education and Sports Unit, Florida Universitaria (Valencia).

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3707-6642

E-mail: arubio@florida-uni.es

Vicenta Ávila

PhD, member of the Reading Research Unit from the University of Valencia. She is an associate professor at the Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Valencia. Her research has focused on the study of reading in early childhood and in population with disabilities.

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2762-2964

E-mail: vicenta.avila@uv.es

Laura Gil

PhD, member of the Reading Research Unit from the University of Valencia (www.uv.es/lectura). She is an associate professor at the Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Valencia. Her research is related to the assessment and intervention of reading comprehension and executive processes.

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0937-6245

E-mail: laura.gil@uv.es

Federica Natalizi

PhD student at the Behavioural Neuroscience program, University of Rome La Sapienza. She holds a master’s degree in Neuroscience and Neuropsicological Rehabilitation. She is a predoctoral researcher at the Neuropsiquiatry Laboratory from the Santa Lucía IRCCS Association. Her research has focused on several cognitive processes in neurodegenerative illness and in the elaboration of interventions aimed at improving cognition and quality of life.

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0139-426X

E-mail: federicanatalizi@gmail.com