Figure 1. Tenets of Service Learning

ANTOINETTE R. SMITH-TOLKEN and MARIANNE MCKAY

Stellenbosch University, South Africa (Stellenbosch, Sudáfrica)

DOI: 10.13042/Bordon.2019.72004

Fecha de recepción: 08/04/2019 • Fecha de aceptación: 09/10/2019

Autora de contacto / Corresponding author: Antoinette R. Smith-Tolken. E-mail: asmi@sun.ac.za

INTRODUCTION. Many universities across the world prefer service learning (SL) as pedagogical framework and practice to integrate community engagement in teaching and learning. The pursuit of reciprocal collaborative relationships with society and the prominence of reflection in bridging the gap between theory and practice are characteristic of this framework. Furthermore, the focus of SL on personal growth, academic learning and social responsibility articulate well with the aim of Higher Education to develop student graduate attributes such as professionalism, critical citizenship and employment competencies. This study explores the mutations of SL in one institution where SL was articulated to be the preferred pedagogical framework for practical components of academic programmes. The question became: Is community-engaged teaching and learning a broader evolving practice of multiple pedagogical approaches in one institution or do they still constitute aspects of SL? METHOD. The study took an explorative interpretive approach to determine if SL was the only pedagogy practiced in the institution and examined the concept of collaborative engaged teaching and learning. It started with a rapid survey of all courses that was offered using experiential pedagogy and a report was compiled. In a follow-up study, specific academic programmes were purposively selected and educators were asked to analyse the approaches they were using. This was followed by purposive open-ended interviews with specific course facilitators about their teaching practice. A round table discussion was held where everyone presented his or her work. RESULTS. Content analysis showed a diversity of learning strategies. It was found that not all courses followed specific service learning methodology, but a mixture of practicums, including internships, community-based learning and work integrated learning. Multiple pedagogical approaches and methodologies were used. During interviews and presentations, it was found, however, that all courses followed at least one of the SL tenets namely service, academic learning, reflection, students developing a social responsibility and competencies. DISCUSSION. Although SL was used as a basis for their teaching/learning strategy, many of the respondents felt they did not practice SL as the latter was experienced as prescriptive and not always applicable in its entirety. Community-engaged teaching and learning (CETL) evolved as an inclusive concept that encompass multiple pedagogies that strengthen the notion of engaged teaching and engaged research as engaged scholarship. A typology of student engagement challenges the Furco (1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service.) depiction of SL and related activities and introduces the new concept of community-engaged teaching and learning.

Keywords: Experiential learning, Service learning, Scholarship, Student engagement.

University-society engagement has become far more than integrating community engagement into teaching and learning. It has grown to new notions of integrating and relating to all spheres of society through both teaching, learning and research while embracing the notion of engaged scholarship and scholarship of engagement (McNall, Reed, Brown & Allen, 2009McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R. E. & Allan, A. (2009). Brokering community-university engagement. Innovation Higher Education, 33, 317-331.; Boyer, 1996Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11-20.). Networks have developed across the world to show solidarity with the notion of university engagement in society. These include Australia Engage, Europe Engage, Asia Engage, Community Knowledge Initiative (CKI) and Centro Latino Apprendizaje y Servicio Solidario (CLAYSS). Most of these regional networks are affiliates of the Talloires Network, a global network of 388 members in 77 countries around the world (https://talloiresnetwork.tufts.edu/). In each of these examples, SL is practiced in different contexts, and thus multiple definitions of SL have evolved from these settings. Similar to the term community engagement, the term SL is used for practices such as community service, volunteerism, community outreach and others.

In developed contexts such as in the United States of America (USA), the term ‘civic engagement’ is more common and refers to a particular way of conducting teaching, research and service with and in communities. The meaning attached to civic engagement is therefore similar to community engagement, but it puts engagement at the centre of all the activities that emanate from core university functions (Hatcher & Erasmus, 2008Hatcher, J. & Erasmus, M. (2008). Service-learning in the United States and South Africa: A comparative analysis informed by Dewey John and Julius Nyerere. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Fall, 49-61. ; Thomson, Smith-Tolken, Naidoo, & Bringle, 2011Thomson, A. M., Smith-Tolken, A., Naidoo, A. & Bringle, R. G. (2011). Service learning and community engagement: A comparison of three national contexts. Voluntas, 22, 214-237.). In these contexts, SL is perceived as a preferred avenue through which civic engagement may be accomplished with students (Kenny & Gallagher, 2002Kenny, M. E. & Gallagher, L. A. (2002). Service learning: A history of systems. In M. Kenny, L. A. K. Simon, K. K. Brabeck & R. M. Lerner (eds.), Learning to serve – Promoting civil society through service learning (pp. 15-30). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic.).

In South Africa (SA), the USA model of SL as learning by doing gradually developed its own ‘African’ flavour by not only perceiving it as learning by doing, but following a more ‘engaged’ way of developing solidarity with community organisations and their constituencies. Here students do not only volunteer their service, but become change agents together with community partners in a post-apartheid society where gross inequalities and poverty prevail in a highly unstable society of attempted state capture and governmental corruption. Aligned to the ‘aprendizaje servicio solidario’ in Latin America, South African SL tend to be leaning towards becoming a vehicle for ‘Ubuntu’ meaning ‘I am because you are’. The importance of students developing critical citizenship and becoming professionals that care, are some of the values that emerged in SA SL practices.

Over time, many forms of experiential learning (EL) have adopted the values and principles of the SL framework such as reflection and collaborative learning with and in communities and industry. In one institution, these different forms of EL do not always fit the definition of SL, but fit the characteristics of being “engaged”, because they rely on well-defined collaboration with industry or non- academic communities beyond the boundaries of the university where students learn. Although SL provides a well-developed pedagogical framework and strategy for student community engagement, non-educationists and many educators find it prescriptive and tedious to apply in some contexts. Just as Le Grange (2007Le Grange, L. (2007). The “theoretical foundations” of community service-learning: From taproots to rhizomes. Education as Change, 11(3), 3-13.) argued that SL should have more than one theoretical grounding, SL may become an anchor pedagogy for more than one practice under the umbrella of community-engaged teaching and learning. Engaged scholarship can be realised through more than one ‘engaged’ pedagogy, which correlates with the global trend of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) favouring a strong relevance to society and graduate attributes of professional conduct and critical citizenship of graduates in society.

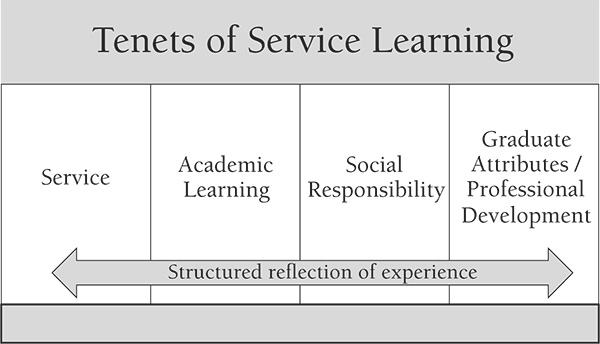

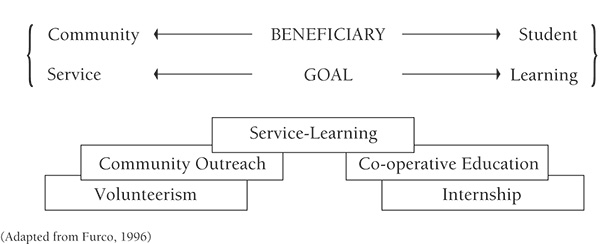

This paper argues for a broader and inclusive concept that encompass all forms of EL taking place outside the classroom and campus including both curricular and co-curricular forms of learning taking place in industry or community organisations. The well-known Furco (1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service.) graphic of student engagement is adapted to demonstrate the different contexts in which EL takes place in one university. The concept Community Engaged Teaching and Learning (CETL) is explored and the definition of Kennesaw State University is used as a point of departure. This states: "Community-Engaged Teaching at KSU denotes curricular and co-curricular instruction that is intentionally designed to meet learning goals while simultaneously fostering reciprocal relationships with a community. In addition, community-engaged teaching is assessable and requires structured reflection by learners. Community-engaged teaching encompasses pedagogical practices such as community-based learning, service-learning, experiential learning, and civic engagement” (Kennesaw State UniversityKennesaw State University, KSU Engage. Retrieved from https://engageksu.kennesaw.edu/engaged-teaching/about.php).

Literature Overview

Encompassing a set of intentional educational objectives, SL is increasingly recognized as a valuable strategy for strengthening both civil society and Higher Education (HE) in the USA and in other parts of the world as mentioned earlier (Astin and Sax, 1998Astin, A. W. & Sax, L. J. (1998). How undergraduates are affected by service participation. Journal of College Student Development, 39, 251-263.). In the past decade, there has been an upsurge of interest in the United Kingdom in ‘third stream’ activity or community engagement by HE institutions. For instance, the ‘Science Shop’ movement in Europe, active since the 1970s, has been reactivated through the International Science Shop Network, and various models of student community engagement and SL from the USA have begun to spread to other parts of the world (Hatcher & Erasmus, 2008Hatcher, J. & Erasmus, M. (2008). Service-learning in the United States and South Africa: A comparative analysis informed by Dewey John and Julius Nyerere. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Fall, 49-61. ; Millican, 2007Millican, J. (2007). Finding commonality among difference – Developing emotional literacy through experiential work (Unpublished document). CUPP, University of Brighton.). There seems to be general agreement that ‘engagement’ between universities and communities is a positive approach which helps address various aims including making science accessible to society, highlighting issues of social justice, encouraging sustainable development and tackling problems of marginalisation and deprivation.

Service Learning

SL, known for providing a bridge between theory and practice, through reflection, builds on Dewey’s educational philosophy that provided principles, values, and a moral basis of how and what education was to become. Dewey’s belief that education should lead to personal growth, contribute to humane conditions, and engage citizens in association with each other is a key characteristic of his educational philosophy (Bringle & Hatcher, 1999Bringle, R. G. & Hatcher, J. A. (1999). Reflection in service-learning: Making meaning of experience. Educational Horizons, 77(4), 179-185.). Eyler (2002Eyler, J. (2002). Reflection: Linking service and learning-Linking students and communities. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 517-534.) alludes to Dewey and the link between the learning process and democratic citizenship of students when they are immersed in worthwhile experiences that stimulate their interest and further inquiry. Felten and Clayton (2011Felten, P. & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 77-84. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.470) affirm Dewey’s work as foundational for the advancement of SL and reflective practice, alongside the contributions of Sigmon (1979Sigmon, R. L. (1979). Service-learning: Three principles. Synergist, 8(1), 9-11.) who helped to establish and formalize the pedagogy and Ehrlich (1996Ehrlich, T. (1996). Foreword . In B. Jacoby & Associates (eds.), Service-learning in higher education: Concepts and practices (p. xi). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.) who provided a general framework for SL.

Bringle and Clayton (2012Bringle, R. G. & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. McIlraith, A. Lyons & R. Munck (eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101–124). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.), adapted a frequently used definition of SL, and expanded on the context within which SL occurs to include more current thinking. Their definition states:

Service-learning is a course or competency-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students (a) participate in mutually identified service activities that benefit the community, and (b) reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content, a broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility (p. 105).

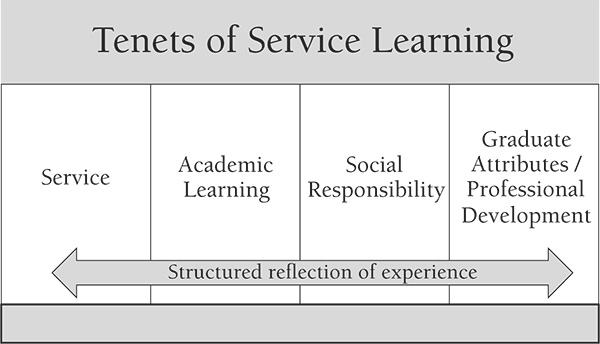

Bringle and Clayton (2012Bringle, R. G. & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. McIlraith, A. Lyons & R. Munck (eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101–124). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.) further state that other definitions do not delimit SL to curricular gains as some emphasize the roles of faculty and community members in the process, while others make social justice or systems change an explicit objective. Felten and Clayton (2011Felten, P. & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 77-84. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.470) echo this view. They state that as the field of SL has matured, the range of its definitions has converged on several core characteristics: service-learning experiences advance both learning goals and community processes. This is possible if collaboration among participants (students, faculty, community members, community organizations, and educational institutions) is inclusive and of a reciprocal nature, resulting in meaningful collaboration to fulfil shared objectives and building capacity among all partners. A central feature in collaborative partnerships is reciprocity that creates a strong connection between the academic context and public concerns. Critical reflection in particular enables and reinforces this linkage and is the component of SL that generates, deepens, and documents learning (Ash & Clayton, 2009; Felten & Clayton, 2011Felten, P. & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 77-84. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.470). Furthermore, the focus of service-learning on personal growth, academic learning and social responsibility articulates well with the aims of HE to develop student graduate attributes such as professionalism, critical citizenship and employment competencies. Service-learning may be content-focused (developing future professionals linking content with practice) or social-change focused (changing status quo in community and developing solidarity between partners) (Osman and Peterson, 2013Osman, R. & Petersen, N. (eds.) (2013). Service learning in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press.). Service-learning experiences also include critical reflection and assessment processes that are purposefully designed and facilitated to produce and document meaningful learning and service outcomes. If well designed and rigorously implemented, reflection is the component of the learning process that generates meaning, new questions, and enhanced understanding of practice. In the light of the above, the tenets of SL are depicted in Figure 1 below. Professional development is one of the more recent impacts of SL that might not fit the original intention of SL as being solely based on interaction with civil society and focused on service rather than development objectives.

|

Figure 1. Tenets of Service Learning

|

Furco (2003Furco, A. (2003). Issues of Definition and Program Diversity in the Study of Service-Learning. In S. H. Billig and A. S. Waterman (eds.), Studying Service-Learning: Innovations in Education Research Methodology. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.) states that one of the greatest challenges in the study of SL is the absence of a common, universally accepted definition for the term. The overarching educational goals of SL are subject to numerous interpretations. It is not surprising that mutations of the pedagogy may prevail. The question is whether SL can have its own identity and simultaneously become one of and potentially the anchor pedagogy of a range of practices under the umbrella of community engaged teaching and learning. From a SA perspective, Le Grange (2007Le Grange, L. (2007). The “theoretical foundations” of community service-learning: From taproots to rhizomes. Education as Change, 11(3), 3-13.) critiques the philosophical thought of Dewey as the only foundation for service-learning and reflection. He argues that “[t]he notion ‘in imitation of’ opens up endless possibilities for enriching SL ‘theoretically,’ linking service-learning to Deweynian thought …” and contends that Dewey’s view is only one of the possible philosophical and theoretical foundations. It opens up other possibilities “in imitation of ” such as “ … service-learning after Dewey, service-learning after Foucault, service-learning after Rorty, service-learning after Nussbaum, and on - the possibilities are infinite” (p. 6). Despite this critique, it is fair to acknowledge Dewey’s contribution to the conceptualization of SL, which also gave impetus to the development of the EL cycle by Kolb (1984Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.) and his predecessors Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget’s learning models. Despite the multiple definitions of SL, one definition of SL (as adapted by Bringle and Clayton above) stood the test of time, albeit with subtle changes mentioned earlier.

Community Engaged Teaching and Learning

When looking at SL and the endless depth and innovation it presents for HE, it is no wonder that scholars who has a grasp of the pedagogy, started to use some of its pedagogical principles and methods in their work with teaching students. However, one of the imperfections of SL is the focus on civil society and ‘communities’ as being the ‘third sector’. Its Deweynian grounding tends to limit it to a pedagogy of human development, delimiting the vast impact HE can have on the rest of society. It is also important to consider factors such as the advancement of scholarship and the foregrounding of community engagement in debates and thinking about the public role of Higher Education institutions in the 21st century, which have become more prominent. Boyer (1996Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11-20.) introduced the concept of scholarship of engagement, rendering service as a catch-all phrase for ‘third stream activity’ in HE inappropriate. He contended that scholarship should be in the centre of all university-societal engagements. McNall et al. (2009McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R. E. & Allan, A. (2009). Brokering community-university engagement. Innovation Higher Education, 33, 317-331.:318) explain engaged scholarship further: “As faculty members, staff, and students have engaged with communities, a new form of scholarship – engaged scholarship - has emerged. It is a form of scholarship that cuts across teaching, research, and service”. To them “engaged scholarship is about the doing of engagement, the scholarship of engagement is about reflecting on and writing about it” (McNall et al., 2009McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R. E. & Allan, A. (2009). Brokering community-university engagement. Innovation Higher Education, 33, 317-331.: 319). In both Australia and South Africa, the notion of social impact through engaged scholarship is growing. The Centre for Social Impact is a collaboration of three universities: UNSW Australia, Swinburne University of Technology and the University of Western Australia. On their website, they state: “We believe everyone has a role to play in creating social change. Our purpose is to catalyse positive social change, to help enable others to achieve social impact https://www.csi.edu.au/about-csi/. In their 2017 annual report, it stated:

Our research develops and brings together knowledge to understand current social challenges and opportunities; our postgraduate and undergraduate education develops social impact leaders; and we aim to catalyse change by drawing on these foundations and translating knowledge, creating leaders, developing usable resources, and reaching across traditional divides to facilitate collaborations (p. 6).

This resonates well with Boyer’s conviction that HE should play an active role in addressing the most pressing challenges in society (Boyer, 1996Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11-20.). In South Africa, Stellenbosch University strives to promote social impact through an evaluative social change strategy working towards the attainment of the sustainable development goals. Engaged scholarship forms the backbone of both these examples and includes both engaged teaching and research. Social Impact is also a much broader conceptualisation of university-society relations. It encompasses a reciprocal impact between a Higher Education institution and society, incurring change through collaboration with societal institutions and structures, engaged scholarship and engaged citizenship (Social Impact Strategic Plan 2017-2022Stellenbosch University (2016). Social Impact Strategic Plan 2017-2022. Retrieved from http://www.sun.ac.za/si/en-za/Documents/SocialImpactStrategicPlan2017-2022_25Nov.pdf ).

It is within this context that the concept of community-engaged teaching and learning evolved. Apart from Kennesaw, other universities use similar definitions of their student engagement. University of Sydney denotes: [We] explore knowledge and develop the skills of enquiry through a diverse array of experiential and applied activities, which we call Community Engaged Learning and Teaching (CELT). These activities take students out of the classroom to learn through partnership projects with business, industry, government, education, non-government and community organisations”. The Southern Cross University describes what they call Community Engaged Learning as the term used to describe contextualised learning experiences for students across a range of communities. The activity is structured, intentional and recognised by the University in order to secure directed learning outcomes for the student that are both transferable and relevant. Stellenbosch University describe Engaged Teaching and Learning as:

“…a form of teaching and learning which may take a curricular or co-curricular character, is assessable for academic credit and includes structured reflection by learners and educators. It is embedded in reciprocal benefit for all involved and encompasses all pedagogical practices that favour experiential type learning where knowledge is socially constructed and activity based. It aims to facilitate student transition from university to workplace, is associated with collaborative teaching practice where professionals in practice become mentors and co-educators of students and provides opportunities for collaborative research that focus on teaching practice. Students are mentored to be a new generation of engaged critical citizens and social change enablers” (Social Impact Strategic Plan 2017-2022Stellenbosch University (2016). Social Impact Strategic Plan 2017-2022. Retrieved from http://www.sun.ac.za/si/en-za/Documents/SocialImpactStrategicPlan2017-2022_25Nov.pdf : 17).

The use of the word ‘community’ distinguishes CETL from the view of engaged learning held by Barnett and Coate (2005Barnett, R. & Coate, K. (2005). Engaging the Curriculum in Higher Education. Berkshire: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.: 123) which related to the way students engage with the curriculum, the student's identity, and unique way of integrating the self into processes of knowing and enquiry.

As literature on CETL is currently limited, more research is necessary to explore this theme further. The research presented in this paper is a preliminary exploration of the term, ‘Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning, including its theoretical grounding and practices.

Research Context and Design

One academic institution is used to illustrate the case. Stellenbosch University (SU) defines itself as a research driven African university in service of all its stakeholders. SL has been part of SU policies and structures since the inception of what was described as ‘community interaction’ and mostly focused on civil society as the focus of its student and staff engagements beyond the boundaries of the campus. As SL was promoted as the preferred way of integrating community interaction into teaching and learning, SL capacity building programmes were offered at this university since 2005. SL was widely practiced, but it was clear that all practical components of its qualification offer, did not follow the SL strategy rigorously. Further exploration proved that even the academics who attended the SL courses, adapted the methodology to fit the individual character of their academic programme. This phenomenon also surfaced in a PhD on scholarly-based service processes (Smith-Tolken, 2010). Mirrored against the Furco (1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service.) depiction of student engagement Figure 2 below), the practices did not fit the types that Furco depicted (Bender, Daniels, Lazarus, Naude & Sattar, 2006Bender, C. J., Daniels, P., Lazarus, J., Naude, L. & Sattar, K. (2006). Service learning in the curriculum. A resource for higher education institutions. Pretoria, South Africa: The Council on Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/HEQC_Service- Learning_Curriculum_Jun2006_0.pdf ), which shows the equal benefit of SL to students and communities. This sparked the question why there was a need to deviate from SL practice.

|

Figure 2. Typology Student Community Engagement

|

An action research process was initiated which later evolved into a mixed methods approach. The study took an explorative interpretive approach, focusing on the meanings that were connected to practicing EL or similar ways of knowing (including SL). A report of a rapid survey of all courses using experiential pedagogy in one institution was used as a background document. In a follow-up study, specific academic programmes were purposively selected and asked to analyse the approaches they were using. This was followed by purposive open-ended interviews with specific course educators about their teaching practice. Each of the respondents signed a consent to participate in the follow-up study and ethical clearance attained for the study. These respondents were also asked to write up a summary of their teaching practice in teaching a course with a practical component. Respondents from seven Faculties were asked to present their practice at a conference round table discussion. Practitioners from the Faculties of Engineering and Education did not participate in the roundtable, but contributed to the diversity of practices in the institution. The data were collated in a table projecting all the different pedagogical approaches they used in their teaching. Some of them also presented some feedback from their students. The data also used to determine patterns in the length and content of the different practices. A new typology framework was developed from the research.

Findings

The main aim of the study was to determine if community-engaged teaching and learning an evolving practice of multiple pedagogical approaches in the institution. The survey provided baseline data that gave an indication of the EL practices in one institution. According to the results, ninety-six (96) courses[1] in eight faculties had an EL component. It was found that forty-one (41) of the courses awarded one or fewer credits to the component, with forty-four (44) awarding more than one credit to experiential activities. In SL courses, at least twenty (20) % of the marks are awarded for SL related activities and outputs (such as journals or assignments). In some cases SL is integrated throughout the whole course in which it would be referred to as a SL-course. Graph 4 depicts that thirty-one (31) courses awarded more than twenty present to the EL component. In some of those courses, SL was integrated into the full credit value of the courses (Community Interaction, 2012Community Interaction (2012). Experiential Learning Survey. Unpublished Report. Stellenbosch University.).

The participants that were purposively invited to participate in the follow-up study, were asked to compile a report with the following information (see table 1 below):

| Table 1. Diversity in Practices Evolving from SL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The results showed a diversity of practices and in some cases more than one practice in one course or academic programme. Some inputs were more elaborate, but the information could be collated in the table.

Sociology: The Sociology course formed part of ten different academic programmes on an exit-level (third year). Students are placed in groups at a community-based organisation where they provide any service the organisation requires to fulfil community development objectives. Students also initiated a research project based on a knowledge gap, which the organisation defined and collaborated with students to find answers. The aim of this SL course was to equip students with the essential knowledge, insights, skills and mind-set in the context of participatory, human-centred and sustainable micro-level development in South Africa. The SL approach was aimed at amalgamating theory, research methodology (community-based collaborative research), with practical experience.

Theology: Similar to Sociology, Theology applies a SL approach took the form of volunteering at faith-based organisations where they used their tacit knowledge to assist in afterschool care consisting of helping children with school homework and teaching them life skills. Students also did a case study analysis, wrote a research essay and an integrated reflexive assignment as part of their academic outputs. The aim of this SL approach is to foster the competencies of working in a team, experiencing cultural diversity in work contexts, organising and managing oneself, demonstrating an understanding of the world as a set of interrelated systems and personal development.

Medicine: In medicine, students spend their fifth year in a rural setting doing a combination of clinical practice in a hospital and in community settings within an Interprofessional education context. This kind of CETL aims to facilitating learning in, with, for and from the community with a focus on reciprocity, sustainability and social accountability while rendering relevant, meaningful and mutually agreed upon service with the community addressing community needs and the learning outcomes of students. It fosters personal growth and the cultivation of relevant competencies in the students while promoting active citizenship and social responsibility.

Forestry: Forestry have a three week workplace-based learning in a government institution where they apply their theoretical knowledge from forestry courses over the four year curriculum on real life plantation practice in order to develop a comprehensive management plan for a specific plantation project. They do a combination of data gathering, spreadsheet modelling and writing with minimal input from lecturers. Their guidance consist on one lecture per week and feedback on written submissions of management plan components. The educator in this course did a graduate research survey on the impact of this course and work-based learning. The survey provided clear indications that students learn from workplace-based learning in terms of understanding forestry as a whole, how to apply their technical knowledge, planning and time management (Ham and Smith-Tolken, 2014Ham, C. & Smith-Tolken, A. R. (2014). Work-integrated learning in forestry education in South Africa: from theory to practice. In International Proceedings, DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). Annual Workshop held in Indonesia, April 2014.).

Viticulture and Oenology: One of the examples of CETL on different levels of an academic programme is that of Viticulture and Oenology. The table above indicates how different pedagogical practices manifest in one programme. Each of the courses have a different aim, a different CETL approach that fit the purpose and specific outcomes that fit the particular course as depicted in Table 2.

| Tabla 2. Diversity of Practices in One Academic Programme | ||||||||||||||||

|

Engaged strategies are layered throughout the programme, culminating in an extended internship (6 months in industry) in the final (fourth year). These strategies include investigations into social issues in Western Cape, Health and Safety Audits in commercial wineries, and SL at the beginning of the second year. There are normally 30-35 students per academic year on the programme. Students are placed in tasting rooms in second year for SL for around a month (a minimum of 25 hours). They will work intermittently during this time, but frequently end up in long-term employment at the farm. The Internship period is from the end of third year to the middle of fourth year, during which time students do not return to campus, but work continuously at the estate/wine farm carrying out viticulture and cellar duties while experiencing the entire harvest process, from grape ripeness monitoring to the finished wine in bottles. They often live on the farms for this period, and earn a cellar-hand’s wage, and will interact intensively with staff on the farm during this time.

What is significant about this internship, is that students learn from practice, conduct a small-scale research project and are mentored during this time by academic staff and wine industry practitioners. Reflections on daily activities and experiences culminate in a reflective report at the end of their internship. McNall, et al. (2009McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R. E. & Allan, A. (2009). Brokering community-university engagement. Innovation Higher Education, 33, 317-331.) stated that an important component of the students’ (as well as staff members) activities is to reflect on their experiences during SL. In this programme, this takes the form of four reflections on the second year SL work in the tasting rooms (before, during and after) in which students analyze intersections (or lack thereof) between their academic work, and their ‘real-life’ experience of wines and consumers. What was also notable was that industry feedback reported that the learning was reciprocal. Winemakers, viticulturalists, farm and cellar workers were often the recipients of learning as a result of interacting with students, who brought with them a wealth of theoretical and research knowledge from their classes. Winemakers, particularly, indicated that it was a pleasure to interact with the interns and hear their views on practices, and apply new techniques as a result. In the small research projects, knowledge was created reciprocally as winemakers suggested, students tested, and results were processed together, leading to valuable new information that was collaboratively constructed through mutually beneficial activity.

Engineering: The four-year Engineering degree provides an option for students to take a gap year after their third year to work in an industry and return to university to complete their studies. Furthermore, third and fourth year students are offered the option to tutor school learners in Mathematics. The approach is co-curricular, but include the earning of credits and reflection on their experience.

Education: In education, teacher training is a combination of teaching practice and SL. Here students work in schools and apart from teaching practice, also develop learning materials to aid the schools where they work.

In all the examples above, it was found that the tenets of SL were aspired to in one or another format and beyond. Activity theory was used as a theoretical grounding for work integrated learning and social constructivist learning surfaced in the courses where student worked in teams. The majority of the courses used reflection as a way to assess learning and assist students to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

The findings showed that, in one institution there are multiple practices that may have evolved from the SL pedagogical framework, but did not strictly comply with the definition of SL. Each of the courses were credit bearing whether they were curricular of co-curricular. The experiences were carefully structured and occurred in a wide variety of community, industry and workplace contexts. The outcomes achieved were skills, competencies, academic learning and application and benefitted both student and societal structure or institution. The type of programmes where these courses were taught represented both professional and non-professional qualifications. Reflections did not just articulate learning, but served as a way to understand the broader society and its systems as well as unintended learning. Although this resonates well with the SL definition of Bringle and Clayton (2012Bringle, R. G. & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. McIlraith, A. Lyons & R. Munck (eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101–124). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.), the practices had a broader context than SL.

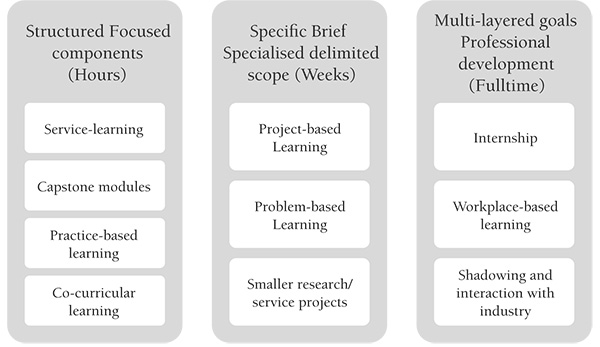

A further analysis of the data culminated in a new typology of CETL where pedagogical practices were distinguished according to their duration, the focus of the engagement and the pedagogical practices that fitted into the three categories as depicted in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3. Typology of Community Engaged Teaching and Learning

|

It was found that service learning, capstone modules, practice-based learning and preparation for practice as in teacher education happened on a regular bases (mostly weekly) where students focus on providing service with a focused aim. A set number of hours has to be fulfilled in this time period. This type of learning is formatively assessed throughout the interaction with a community with a summative assessment in the form of a portfolio. One group of students follows through on their predecessors’ work and the project continues to roll over from semester to s when the new group fulfils their task at the organisation. In the second category, students are given a specific brief where they engage in a specialised activity for a number of weeks. This type of engagement is focused on a problem of project that has a specific start and a completion date. In the third category, the focus is multi-layered, for longer periods and on a fulltime basis for a set period. It was found that the layers in this type of engagement could include some of the other categories. The conclusion is that community-engaged teaching and learning is an evolving practice of multiple pedagogical approaches in one institution through mutations of the SL pedagogical practice. A more appropriate definition would be that community-engaged teaching and learning is a form of engaged scholarship though engaged teaching and learning that may take a curricular or co-curricular character, is assessable for academic credit and includes structured reflection by learners and educators. Reciprocal benefit for all stakeholders are embraced and it encompasses all pedagogical practices that favour an experiential type of learning where knowledge is socially constructed and activity based. It aims to facilitate student transition from university to workplace, is associated with collaborative teaching practice where professional practitioners become mentors and co-educators of students and provides opportunities for collaborative research that focus on teaching practice. New knowledge may be created. Students are mentored to be a new generation of engaged critical citizens and social change enablers.

The limitations of the study is that it was done in one university and could have included feedback from more stakeholders. A much broader study, inclusive of exploring the theoretical grounding of the respective pedagogical practices and funded by a research foundation, is underway. More research on the topic is imminent and is encouraged.

| [1] Please note that in the context of the study, courses also refer to modules. |

| ○ | Astin, A. W. & Sax, L. J. (1998). How undergraduates are affected by service participation. Journal of College Student Development, 39, 251-263. |

| ○ | Barnett, R. & Coate, K. (2005). Engaging the Curriculum in Higher Education. Berkshire: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press. |

| ○ | Bender, C. J., Daniels, P., Lazarus, J., Naude, L. & Sattar, K. (2006). Service learning in the curriculum. A resource for higher education institutions. Pretoria, South Africa: The Council on Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/HEQC_Service- Learning_Curriculum_Jun2006_0.pdf |

| ○ | Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach, 1(1), 11-20. |

| ○ | Bringle, R. G. & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. McIlraith, A. Lyons & R. Munck (eds.), Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101–124). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. |

| ○ | Bringle, R. G. & Hatcher, J. A. (1999). Reflection in service-learning: Making meaning of experience. Educational Horizons, 77(4), 179-185. |

| ○ | Community Interaction (2012). Experiential Learning Survey. Unpublished Report. Stellenbosch University. |

| ○ | Council on Higher Education (2010). Higher Education in South Africa 2008. Retrieved from http://www.che.ac.za/heinsa/ |

| ○ | Ehrlich, T. (1996). Foreword . In B. Jacoby & Associates (eds.), Service-learning in higher education: Concepts and practices (p. xi). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. |

| ○ | Eyler, J. (2002). Reflection: Linking service and learning-Linking students and communities. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 517-534. |

| ○ | Felten, P. & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 128, 77-84. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.470 |

| ○ | Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service. |

| ○ | Furco, A. (2003). Issues of Definition and Program Diversity in the Study of Service-Learning. In S. H. Billig and A. S. Waterman (eds.), Studying Service-Learning: Innovations in Education Research Methodology. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. |

| ○ | Ham, C. & Smith-Tolken, A. R. (2014). Work-integrated learning in forestry education in South Africa: from theory to practice. In International Proceedings, DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). Annual Workshop held in Indonesia, April 2014. |

| ○ | Hatcher, J. & Erasmus, M. (2008). Service-learning in the United States and South Africa: A comparative analysis informed by Dewey John and Julius Nyerere. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Fall, 49-61. |

| ○ | Kennesaw State University, KSU Engage. Retrieved from https://engageksu.kennesaw.edu/engaged-teaching/about.php |

| ○ | Kenny, M. E. & Gallagher, L. A. (2002). Service learning: A history of systems. In M. Kenny, L. A. K. Simon, K. K. Brabeck & R. M. Lerner (eds.), Learning to serve – Promoting civil society through service learning (pp. 15-30). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic. |

| ○ | Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. |

| ○ | Le Grange, L. (2007). The “theoretical foundations” of community service-learning: From taproots to rhizomes. Education as Change, 11(3), 3-13. |

| ○ | McNall, M., Reed, C. S., Brown, R. E. & Allan, A. (2009). Brokering community-university engagement. Innovation Higher Education, 33, 317-331. |

| ○ | Millican, J. (2007). Finding commonality among difference – Developing emotional literacy through experiential work (Unpublished document). CUPP, University of Brighton. |

| ○ | Osman, R. & Petersen, N. (eds.) (2013). Service learning in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. |

| ○ | Sigmon, R. L. (1979). Service-learning: Three principles. Synergist, 8(1), 9-11. |

| ○ | Stellenbosch University (2016). Social Impact Strategic Plan 2017-2022. Retrieved from http://www.sun.ac.za/si/en-za/Documents/SocialImpactStrategicPlan2017-2022_25Nov.pdf |

| ○ | Thomson, A. M., Smith-Tolken, A., Naidoo, A. & Bringle, R. G. (2011). Service learning and community engagement: A comparison of three national contexts. Voluntas, 22, 214-237. |

Ser o no ser. Aprendizaje-servicio en una institución de educación superior

INTRODUCCIÓN. Muchas universidades de todo el mundo eligen el aprendizaje-servicio (ApS) como marco pedagógico y práctica educativa para integrar el compromiso con la comunidad en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. La búsqueda de relaciones de colaboración recíproca con la sociedad y la importancia de la reflexión para cerrar la brecha entre la teoría y la práctica son características de este marco. Además, el enfoque del ApS en el crecimiento personal, el aprendizaje académico y la responsabilidad social se articulan bien con el objetivo de la educación superior de desarrollar competencias de los estudiantes de Grado tales como profesionalidad, ciudadanía crítica y competencias para el empleo. Este estudio explora las mutaciones del ApS en una institución donde la metodología se articuló para ser el marco pedagógico preferido para cuestiones prácticas de los programas académicos. La pregunta era: ¿El proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje comprometido con la comunidad una práctica en evolución que abarca múltiples enfoques pedagógicos en una institución o estos son aspectos del ApS? MÉTODO. El estudio adoptó un enfoque interpretativo exploratorio para determinar si el ApS era la única pedagogía que se utilizaba en la institución y examinó el concepto de enseñanza y aprendizaje comprometido y colaborativo. Comenzó con una encuesta breve de todos los cursos ofertados que utilizaban la pedagogía experiencial y se elaboró un informe. En un estudio de seguimiento, se seleccionaron deliberadamente programas académicos específicos y se pidió a los docentes que analizaran los enfoques que estaban utilizando. Esto fue seguido por entrevistas con preguntas abiertas con facilitadores de cursos específicos sobre su práctica docente. Se llevó a cabo una mesa redonda donde todos presentaron su trabajo. RESULTADOS. El análisis de contenido mostró una diversidad de estrategias de aprendizaje. Se descubrió que no todos los cursos seguían una metodología de aprendizaje-servicio específica, sino una combinación de prácticas, incluidas pasantías, aprendizaje basado en la comunidad y aprendizaje integrado en el trabajo. Se utilizaron múltiples enfoques y metodologías pedagógicas. Sin embargo, durante las entrevistas y presentaciones se encontró que todos los cursos seguían al menos uno de los principios del ApS; a saber, el servicio, el aprendizaje académico, la reflexión, desarrollo de la responsabilidad social y de competencias por parte de los estudiantes. DISCUSIÓN. Si bien el ApS se utilizó como base para su estrategia de enseñanza-aprendizaje, muchos de los encuestados sentían que no practicaban ApS, ya que este se percibía como prescriptivo y no siempre aplicable en su totalidad. La enseñanza-aprendizaje comprometida con la comunidad (CETL) evolucionó como un concepto inclusivo que abarca múltiples pedagogías que fortalecen las nociones de enseñanza e investigación comprometidas como educación comprometida. Un tipo de participación estudiantil desafía la descripción de Furco (1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service.) del ApS y actividades relacionadas e introduce el nuevo concepto de enseñanza-aprendizaje comprometido con la comunidad.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje experiencial, Aprendizaje-servicio, Academia, Participación estudiantil.

Être ou ne pas être. Apprentissage-Service dans un établissement d'enseignement supérieur

INTRODUCTION. De nombreuses universités à travers le monde ont opté par l'apprentissage-service (ApS) comme cadre pédagogique et pratique pour intégrer le compromis communautaire dedans l'enseignement et l'apprentissage. La quête de relations de collaboration réciproques avec la société, d’un côté, et l’importance de la réflexion pour combler le fossé entre la théorie et la pratique, d’un autre côté, sont caractéristiques de ce cadre. En outre, l'accent mis par ApS sur la croissance personnelle, l'apprentissage académique et la responsabilité sociale s'articule bien grâce à l'objectif de l'enseignement supérieur de développer les caractéristiques des étudiants diplômés tels que le professionnalisme, la citoyenneté critique et les compétences professionnelles. Cette étude explore les mutations de l’ApS dans une institution où l’ApS a été défini comme étant le cadre pédagogique privilégié pour les éléments pratiques des programmes académiques. La question est alors la suivante: l’enseignement et l’apprentissage engagés pour la communauté sont-ils une pratique évolutive plus large et font-ils appel à de multiples approches pédagogiques dans une même institution ou, par contre. constituent-ils toujours des aspects de l’ApS? MÉTHODE. L’étude a adopté une approche exploratoire interprétative pour déterminer si l’ApS était la seule pédagogie pratiquée dans l’institution et a examiné les concepts d’enseignement et d’apprentissage collaboratifs et engagés. Tout a commencé par une rapide étude de tous les cours offerts sur une pédagogie basée sur l'expérience. Finalement, un rapport a été établi. Dans une étude de suivi, des programmes académiques spécifiques ont été sélectionnés délibérément et les éducateurs ont été invités à analyser les approches qu’ils utilisaient. Cela a été suivi d’entrevues ouvertes concernant la pratique d’enseignement de quelques animateurs des cours. Une table ronde a eu lieu afin de que chacun présente son travail. RÉSULTATS. L'analyse du contenu a révélé une diversité de stratégies d'apprentissage. Il a été constaté que tous les cours ne suivaient pas une méthodologie spécifique pour l’apprentissage-service, mais plutôt une combinaison de pratiques, y compris de stages, d’apprentissage communautaire et d’apprentissage intégré au travail. De multiples approches et méthodologies pédagogiques ont été utilisées. Au cours des entretiens et des présentations, il a toutefois été constaté que tous les cours suivaient au moins l’un des principes de l’ApS; à savoir : le service, l’apprentissage académique, la réflexion, le développement de la responsabilité sociale et des autres compétences. DISCUSSION. Bien que l’ApS ait été utilisé comme base pour leur stratégie d'enseignement-apprentissage, beaucoup de répondants ont estimé qu'ils ne pratiquaient pas l’ApS, étant considéré comme normatif et pas toujours applicable dans sa totalité. L’enseignement et l’apprentissage impliqués à la communauté a évolué pour devenir un concept inclusif qui englobe de multiples pédagogies qui renforcent la notion d’enseignement engagé et de recherche engagée en tant que chercheur engagé. Une typologie de l'engagement des élèves remet en question la description de ApS et des activités connexes décrits par Furco (1996Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education. Expanding Boundaries. Service and Learning, 2-6. Washington DC: Corporation for National Service.) et introduit le nouveau concept d'enseignement et d'apprentissage axé sur la communauté.

Mots-clés: Apprentissage expérientiel, Apprentissage-service, Académie, Engagement de l’étudiant.

Antoinette R. Smith-Tolken (corresponding author)

Antoinette holds a Master of Philosophy degree in Sociology and a PhD in Education (Curriculum Studies) from Stellenbosch University. She retired at the end of 2018 after holding different senior managerial positions in the Division for Social Impact the last five years. She pioneered service-learning in her own institution and is the co-founder of the International Symposium for Service-Learning being held on four continents and for the seventh time in Galway Ireland in 2017. She has more than ten years teaching experience in both undergraduate and graduate classes. Her research record reflects several national and international publications.

E-mail: asmi@sun.ac.za

Correspondence address: Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Stellenbosch University. P O Box 2052, Dennesig. 7601 South Africa.

Marianne McKay

Senior Lecturer, Department of Viticulture and Oenology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

Marianne has a BSc in Chemistry and Geography from University of Cape Town, and an MSc(Agric) from Stellenbosch University (SU). She has worked in various capacities in South Africa and the UK as scientific officer, scientific validation manager and lecturer in wine sciences . Her research has taken her from wine chemistry and sensory evaluation to engaged teaching and learning. She is a Distinguished Teacher (2017) and a Teaching Fellow (2016 - 2019) at SU.

E-mail: marianne@sun.ac.za