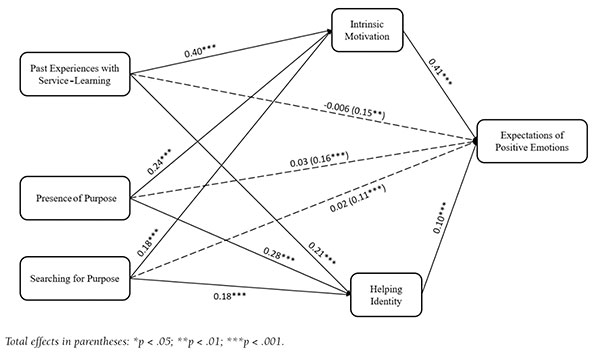

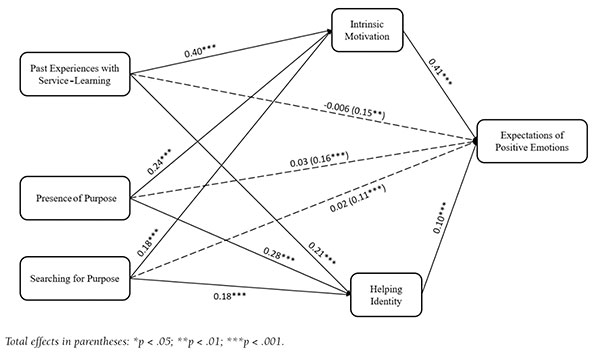

Figure 1A. This figure depicts the mediation model tested for expectations of positive emotions

SEANA MORAN(1) AND RANDI GARCIA(2)

(1) Clark University (Worcester, Massachusetts, USA)

(2) Smith College (Northampton, Massachusetts, USA)

DOI: 10.13042/Bordon.2019.70425

Fecha de recepción: 03/02/2019 • Fecha de aceptación: 23/07/2019

Autora de contacto / Corresponding author: Seana Moran. E-mail: seanamoranclarku@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION. Few studies consider how purpose in life predicts emotions related to community service in college courses even though a purpose in life, a “compass” for finding opportunities to make meaningful prosocial contributions, should motivate students to serve. METHOD. Multilevel structural equation modeling estimated direct and indirect effects of survey responses regarding students’ past service experience, sense of purpose, and searching for purpose on their emotional expectations for service-learning before starting. RESULTS. Controlling for age, gender, extrinsic motivation, and characteristics of universities and courses, students’ past service experience and two purpose variables positively related to expected positive emotions toward service work, mediated through both students’ helping identity and intrinsic motivation to serve. Only sense of purpose was associated with higher intrinsic motivation, which was associated with lower expected negative emotions. DISCUSSION. Considering students’ life purpose may stimulate intrinsic motivation and schemas of being a helping person, which could contribute to positive emotions toward community service even before the service work begins.

Keywords: Youth purpose, Service-learning, Postsecondary education, Prosocial behavior.

Life Purpose and Service-Learning

Conceptually, service-learning is considered a pioneering educational experience for purpose development (Moran, 2018Moran, S. (2018). Purpose-in-action education. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 145-158. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1444001). Students (Moran, 2010Moran, S. (2010). Changing the world: Tolerance and creativity aspirations among American youth. High Ability Studies, 21(2), 117-132. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2010.525342) and teachers (Moran, 2016Moran, S. (2016). What do teachers think about youth purpose? The Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(5), 582-601. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2016.1226556) recognize that service offers opportunities for students to gain feedback on their efforts to help others. In turn, their developing purposes can direct students toward further prosocial opportunities.

Numerous studies have investigated various antecedent behaviors and attitudes for why college students enter service-learning (Clary et al., 1998Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J. & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516-1530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516; Cruce & Moore, 2012Cruce, T. M. & Moore, J. V. (2012). Community service during the first year of college: What is the role of past behavior? Journal of College Student Development, 53(1), 399-417. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0038). But students’ sense of life purpose, a meaningful direction toward contributing prosocially, has received scant attention (Moran, 2019Moran, S. (2019). Youth life purpose: Evaluating service-learning via development of lifelong “radar” for community contribution. In P. Aramburuzabala, L. McIlrath & H. Opazo (eds.), Embedding service-learning in European higher education. Abington, UK: Taylor & Francis.). Purpose variables have been studied as equating volunteering with purpose (Barber, Mueller & Ogata, 2013Barber, C. B., Mueller, C. T. & Ogata, S. (2013). Volunteerism as purpose. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.772775); an outcome of service (Malin, Ballard & Damon, 2015Malin, H., Ballard, P. J. & Damon, W. (2015). Civic purpose. Human Development, 58, 103-130. doi: 10.1159/000381655; Malin, Han & Liauw, 2017Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322; Whitley, 2014Whitley, M. A. (2014). A draft conceptual framework of relevant theories to inform future rigorous research on student service-learning outcomes. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 19-40.), including two studies in Spain (Folgueiras & Palou, 2018Folgueiras, P. & Palou, B. (2018). An exploratory study of aspirations for change and their effect on purpose among Catalan university students. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 186-200. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1433643; Opazo, Aramburuzabala & Ramírez, 2018Opazo, H., Aramburuzabala, P. & Ramírez, C. (2018). Emotions related to Spanish student-teachers’ changes in life purposes following service-learning participation. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 217-230. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1438992); and a mediator between hours of past service and future service (Rockenbach, Hudson & Tuchmayer, 2014Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D. & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and enduring commitments to community service in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2014.11777330) or between identity salience of volunteering and sense of mattering to others (Thoits, 2012Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75, 360-384. doi: 10.1177/0190272512459662). But we found only one study where a purpose-like variable was a predictor of service-learning participation (Hill, Burrow, Brandenberger, Lapsley & Quaranto, 2010Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001).

A developing or fully-formed life purpose can influence students entering service. Purpose helps individuals perceive opportunities to enact, or at least practice, prosocial contributions through everyday actions (Kiang, 2011Kiang, L. (2011). Deriving daily purpose through daily events and role fulfillment among Asian American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 185-198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00767.x; Steger, Kashdan & Oishi, 2008Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B. & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 22-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004), proactively seek service opportunities (Moran, Bundick, Malin & Reilly, 2013Moran, S., Bundick, M. J., Malin, H. & Reilly, T. S. (2013). How supportive of their specific purposes do youth believe their family and friends are? Journal of Adolescent Research, 28(3), 348-377. doi: 10.1177/0743558412457816), receive feedback on the effects of their efforts, and thereby strengthen the meaningfulness and intentionality of their life purpose (Moran, 2017Moran, S. (2017). Youth purpose worldwide. Journal of Moral Education, 46(3), 231-244. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2017.1355297; Opazo, Aramburuzabala & Ramírez, 2018Opazo, H., Aramburuzabala, P. & Ramírez, C. (2018). Emotions related to Spanish student-teachers’ changes in life purposes following service-learning participation. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 217-230. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1438992 ).

Purpose affords self-efficacy that purposeless students may lack (Dobrow Riza & Heller, 2014Dobrow Riza, S. & Heller, D. (2015). Follow your heart or your head? A longitudinal study of the facilitating role of calling and ability in the pursuit of a challenging career. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 695-712. doi: 10.1037/a0038011), so counterintuitively, purposeful students may already see themselves as agentic contributors to society (Quinn, 2013Quinn, B. (2013). Other-oriented purpose. Youth & Society, 46(6), 779-800. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12452435). Life purpose helps individuals persevere during challenges or when supports are scarce. For example, purpose has mitigated downward trends in community service (Vogelgesang & Astin, 2005Vogelgesang, L. J. & Astin, A. W. (2005). Post-college civic engagement among graduates. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles.), civic engagement (Malin et al., 2017Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322), and sense of power to have a positive effect in the world (Miller, 1997Miller, J. (1997). The impact of service-learning experiences on students' sense of power. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 4, 16-21.). By keeping in mind the long-term contributions students aim to make, purpose may buffer students from emotional difficulties of service work (Seider, 2008Seider, S. (2008). ‘Bad things could happen’: How fear impedes the development of social responsibility in privileged adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(6), 647-666. doi: 10.1177/0743558408322144). Students may enter service with a) purpose that can frame the experience using a future vision of themselves, or b) uncertainty regarding the service’s connection to their future.

Development and Functions of Life Purpose

Purpose orients individuals toward a life course both personally meaningful and prosocial to steer their efforts to pursue the purpose despite fluctuations in external support. But life purpose develops over time through experience (Malin, Reilly, Quinn & Moran, 2014Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B. & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186-199. doi: 10.1111/jora.1205). Scholars have proposed various models of purpose development. Integrating these models produces a generalized model of three stages.

First, a person searches for and finds a sense of purpose (Steger, Kashdan & Oishi, 2008Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B. & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 22-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004). Searching for purpose can provoke anxiety and suffering (Blattner, Liang, Lund & Spencer, 2013Blattner, M. C. C., Liang, B., Lund, T. & Spencer, R. (2013). Searching for a sense of purpose. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 839-848. doi: 10.1016/adolescence.2013.06.008) until the person gains a sense of purpose and commits to a specific life aim, which relates to positive feelings that can continue through adulthood (Bronk, Hill, Lapsley, Talib & Finch, 2009Bronk, K. C., Hill, P., Lapsley , D., Talib, T. & Finch, W. H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 500-510. doi: 10.1080/17439760903271439; Hill, Burrow, Brandenberger, Lapsley & Quaranto, 2010Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001). Structured activities to focus exploration, allow proactive engagement, and provide feedback can help searchers find a purpose (Malin et al., 2014Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B. & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186-199. doi: 10.1111/jora.1205; Moran, 2016Moran, S. (2016). What do teachers think about youth purpose? The Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(5), 582-601. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2016.1226556).

Second, a purpose integrates four dimensions: personal meaningfulness (“this is important to me”), intention (“I am going to pursue this aim into the future”), engagement (“I am going to act on and not just dream about it”), and beyond-the-self impact (“my actions aim to help others or society”) (Damon, 2008Damon, W. (2008). The path to purpose. New York, NY: Free Press.). Any dimension could launch a nascent purpose (Moran, 2017Moran, S. (2017). Youth purpose worldwide. Journal of Moral Education, 46(3), 231-244. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2017.1355297), although adolescence may have optimal periods for each dimension: initiating beyond-the-self orientation in ages 11-13, exploring roles to pursue a meaningful aim in ages 14-16, reflecting on priorities after secondary graduation in ages 17-18, and finding supportive pathways forward during college (Malin et al., 2014Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B. & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186-199. doi: 10.1111/jora.1205). Service is one of few educational experiences that can address all four of these dimensions: it involves engagement with beyond-the self impact, can stimulate emotional meaning, and supports intentions to make the world better (Moran, 2018Moran, S. (2018). Purpose-in-action education. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 145-158. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1444001).

Third, commitment to purpose and purpose’s influence in one’s life can build. Purpose becomes sustainable by finding aligned venues to act, increases through positive feedback, and changes via critical incidents or additional resources (Bronk, 2012Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27, 78-109. doi: 10.1177/0743558411412958). Purpose can also broaden the scope of life domains it influences, the strength of its influence on perception and behavior, and how well it is articulated (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009McKnight, P. E. & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 13, 242-251. doi: 10.1037/a0017152). Eventually, purpose can become reciprocally reinforcing with identity (Burrow & Hill, 2011Burrow, A. L. & Hill, P. L. (2011). Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1196-1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818; Kiang & Fuligni, 2010Kiang, L. & Fuligni, A. (2010). Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1253-1264. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z).

Even before service work starts, purpose can help students “make sense” of the opportunity by connecting service to other meaningful life goals. Students entering service with more developed purposes may be able to harness more personal capabilities and resources for the service work (Han, 2015Han, H. (2015). Purpose as a moral virtue for flourishing. Journal of Moral Education, 44(3), 291-309. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2015.1040383). Even students searching for purpose may benefit from exposure to possible roles and pathways (Reinders & Youniss, 2006Reinders, H. & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 2-12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1). But purpose’s first task may be to encourage emotional investment in service.

Emotions Related to Service and Life Purpose

Many studies of service focus on “intent to serve” (e.g., Stukas, Snyder & Clary, 1999Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M. & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of "mandatory volunteerism" on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59-64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00107). But since our interest is in students already enrolled in service-learning courses, we know they will serve. Our focus is their anticipated feelings about their upcoming service and whether purpose relates to those emotions. Prosocial orientation in college predicts emotional well-being in adulthood (Hill et al., 2010Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001), and sense of purpose generally correlates with higher positive emotions and lower negative emotions (King, Hicks, Krull & Del Gaiso, 2006King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L. & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179-196. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179; Ryff & Singer, 2008Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13-39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0).

Emotions help individuals plan for future experiences by learning from current experiences—in particular, by selecting how to act in anticipation of generating specific emotions (Baumeister, Vohs, DeWall & Zhang, 2007Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., DeWall, C. N. & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167-203. doi: 10.1177/1088868307301033). Negative emotions suggest a need to avert threats or rethink one’s direction, whereas positive emotions validate one’s current trajectory (Baumeister et al., 2007Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., DeWall, C. N. & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167-203. doi: 10.1177/1088868307301033) plus “broaden and build” a person’s perceptivity, behavioral flexibility, and resilience (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh & Larkin, 2003Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E. & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365-376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365).

Interacting directly with those whom students expect will benefit from their service can be emotionally complex (Darby, Perry & Dinnie, 2015Darby, A., Perry, S. & Dinnie, M. (2015). Students’ emotional experiences in direct versus indirect academic service-learning courses. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 3(1).) and produce “emotional shocks” student may cope with and stay engaged (Rockquemore & Schaffer, 2003Rockquemore, K. A. & Schaffer, R. H. (2000). Toward a theory of engagement. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 7, 1425.) or quit from anxiety (Seider, 2008Seider, S. (2008). ‘Bad things could happen’: How fear impedes the development of social responsibility in privileged adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(6), 647-666. doi: 10.1177/0743558408322144). Students may experience negative emotions related to conditions in the community, yet concurrently feel positively about their role in helping alleviate those conditions (Harre, 2007Harre, N. (2007). Community service or activism as an identity project for youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(6), 711-724. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20174; Reinders & Youniss, 2006Reinders, H. & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 2-12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1). Volunteering creates meaningful positive emotions that last until the following day (Steger et al., 2008Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B. & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 22-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004). Two small-sample, qualitative studies suggest that “trigger events” producing emotional intensity can change a person’s purpose (Bronk, 2012Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27, 78-109. doi: 10.1177/0743558411412958), and “frame-changing experiences” shifting students’ conceptions of their own role in the community may emotionally influence their commitment to social action (Seider, 2007Seider, S. (2007). Frame-changing experiences and the freshman year: Catalyzing a commitment to service-work and social action. Journal of College & Character, 8, 1-15. doi: 10.2202/1940-1639.1168).

Other Contributing Factors

Prior service experience. Students already familiar with service work are more likely to continue community contributions in the future (Hart, Donnelly, Youniss & Adkins, 2007Hart, D., Donnelly, T. M., Youniss, J. & Atkins, R. (2007). High school community service as a predictor of adult voting and volunteering. American Educational Research Journal, 44(1), 197-219. doi: 10.3102/0002831206298173), and the more hours of service before college, the stronger the probability of continuing in college (Cruce & Moore, 2012Cruce, T. M. & Moore, J. V. (2012). Community service during the first year of college: What is the role of past behavior? Journal of College Student Development, 53(1), 399-417. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0038). This effect of prior service could be from forming a mindless habit that is enacted later with similar environmental cues or from developing to a mindful future-oriented purpose, each which can have differential effects on anticipated emotion (Wood, Quinn & Kashy, 2002Wood, W., Quinn, J. M. & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Habits in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1281-1297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1281 ). Habits do not generally elicit emotions, so without external motivators, subsequent service may not occur. Purpose’s personal meaning dimension keeps in mind the emotional resonances of one’s prosocial contributions as reference points for perceiving subsequent opportunities to serve. Generally, there is a downward trend in community service from adolescence into adulthood (Vogelgesang & Astin, 2005Vogelgesang, L. J. & Astin, A. W. (2005). Post-college civic engagement among graduates. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles.), suggesting many students’ prior service experiences generate habits that are not activated as other life responsibilities emerge. But purpose development may stall that downward trend (Malin et al., 2017Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322; Rockenbach et al., 2014Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D. & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and enduring commitments to community service in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2014.11777330).

Extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is doing a task for a reward or a requirement. Individuals feel controlled by the motivator and less positively toward the task. Extrinsic motivators may be obstacles to launching a purpose, but students already with a sense of purpose should be less swayed by extrinsic motivators because their purpose orients them toward relevant, meaningful opportunities (Moran et al., 2013Moran, S., Bundick, M. J., Malin, H. & Reilly, T. S. (2013). How supportive of their specific purposes do youth believe their family and friends are? Journal of Adolescent Research, 28(3), 348-377. doi: 10.1177/0743558412457816). Furthermore, life goals oriented toward extrinsic rewards like wealth or fame do not provide the well-being benefits of prosocial purposes (Hill et al., 2010Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001; Kasser & Ryan, 1996Kasser, T. & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280-287. doi: 10.1177/0146167296223006).

College students not interested in volunteering but required to serve were less likely to intend to volunteer later than those who choose to volunteer, but requirement versus choice made no difference to those who were already interested in volunteering (Stukas et al., 1999Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M. & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of "mandatory volunteerism" on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59-64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00107). Students who served for self-oriented benefits or because others wanted or required them to serve were also less likely to continue community involvement than students who believed in the cause, social change, or citizenship (Soria & Thomas-Card, 2014Soria, K. M. & Thomas-Card, T. (2014). Relationships between motivations for community service participation and desire to continue service following college. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 53-64.). Yet, extrinsic motivators may initiate students searching for a purpose, who may not otherwise serve, to the possibilities of “doing good” (Reinders & Youniss, 2006Reinders, H. & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 2-12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1).

Intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is a relationship between person and task in that the person enjoys the task or finds it emotionally important. Students serving others for enjoyment or importance reasons tended to see themselves contributing further in the future (Soria & Thomas-Card, 2014Soria, K. M. & Thomas-Card, T. (2014). Relationships between motivations for community service participation and desire to continue service following college. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 53-64.; Stukas et al., 1999Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M. & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of "mandatory volunteerism" on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59-64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00107). Intrinsic motives also tend to sustain purposes focused on supporting “the common good” (Malin et al., 2017Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322).

Helping identity. A helping identity is a relationship between person and role in that the person views a social role as part of one’s self. Life purpose supports identity (Bronk, 2011Bronk, K. C. (2011). The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: A grounded model. New Directions for Youth Development, 132, 31-44. doi: 10.1002/yd.426; McKnight & Kashdan, 2009McKnight, P. E. & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 13, 242-251. doi: 10.1037/a0017152). Similarly, regular engagement in service has been framed in terms of identity development (Bronk, 2012Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27, 78-109. doi: 10.1177/0743558411412958; Harre, 2007Harre, N. (2007). Community service or activism as an identity project for youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(6), 711-724. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20174; Reinders & Youniss, 2006Reinders, H. & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 2-12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1). A few studies suggest that purpose mediates identity and well-being. Once a person identifies with a role, it becomes more meaningful and satisfying to enact the role because “it’s just who I am” (Thoits, 2012Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75, 360-384. doi: 10.1177/0190272512459662), and both purpose and identity contribute to more positive emotion and less negative emotion over time (Burrow & Hill, 2011Burrow, A. L. & Hill, P. L. (2011). Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1196-1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818).

Research Questions and Hypotheses

To what degree does having a sense of purpose or searching for a purpose relate to college students’ emotional expectations of upcoming community service work?

H1: Because both purpose and service address engagement to benefit others, we hypothesize that sense of purpose will correlate strongly with positive feelings toward service work.

H2: Because service-learning provides structure for exploring prosocial action, we hypothesize that searching for purpose will also correlate with positive feelings toward service work, albeit weaker.

As a long-term life aim, does purpose directly influence emotions toward an upcoming service experience, or is purpose’s role eclipsed by more proximal influences like motivation or role identity?

H3: Because of the interrelationships between life purpose, service, motivation, identity, and emotions, we hypothesize that the relationship between life purpose and anticipated emotions toward service are partially mediated by more proximal influences.

Participants

Demographics split by university appear in table 1. Nested within 2 universities and 74 community-engaged courses ranging in size from 2 to 74 students, 780 students took a pre-service online survey. 174 students (22.3%) were from a small private university and 606 (77.7%) were from a large public university. The public university sample included students in both student skill-development-oriented experiential learning courses (n = 237, 39.1%) and community-oriented service-learning courses (n = 369, 60.9%). All of the private university students were in service-learning courses. 63.3% reported that their course was required for their major or for graduation.

The average age of the total sample was 23.70 (Mdn = 22), ranging from 18 to 60 years. Males comprised 215 (27.8%) and females 531 (71.2%) of participants, with 34 (4.4%) students not indicating a gender. Racial identification ranged from 472 (60.5%) White/European-American, 80 (10.3%) Hispanic/Latino, 51 (6.5%) Asian/Asian-American, 47 (6.0%) multiracial, 44 (5.6%) Black/African-American, to 9 (1.2%) Middle Eastern/Arab, and 77 (9.9%) did not indicate race.

There was a relatively even distribution of class years with a slight skew toward upperclassmen: first years (n = 110, 14.1%), sophomores (n = 87, 11.2%), juniors (n = 172, 22.1%), seniors (n = 192, 24.6%), and graduate students (n = 181, 23.2%), with 38 (4.9%) not indicating class year. Declared majors included social sciences (n = 228, 29.2%), business (n = 167, 21.4%), education (n = 135, 17.3%), healthcare (n = 71, 9.1%), natural sciences (n = 54, 6.9%), humanities (n = 47, 6.0%), engineering (n = 26, 3.3%), and mathematics (n = 12, 1.5%), with 40 (5.1%) not indicating major.

| Table 1. Demographics by University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sampling and Data Collection Procedure

This study is part of a six-country data collection collaboration to survey students at three points during service-learning or experiential learning courses. Courses were recruited through professors. Professors were provided a small cash gratuity, but professors were not involved in data collection and had no access to data. Research colleagues made presentations within these courses to invite students to voluntarily participate. All students in a course were sent the first survey, which required consent to participate and consent to how they would allow their data to be used (no consent, use only for learning about themselves, allow their responses to be aggregated and analyzed). Data for students who did not allow analysis were removed.

Only students who consented and completed the first survey were sent the second and third surveys. Surveys were timed to before students started service, about halfway through their service, and after or near the end of service. Students could remove themselves from the study at any time. Surveys were conducted online through links sent by email using Qualtrics survey software. Reminders were sent every week to consenting participants who had not yet finished the survey.

This paper’s analyses only used data collected in two universities in the United States. We used responses to select questions from the first survey—about participant demographics, history of and motivations for service, what participants expect to feel while serving, as well as their sense of having or searching for life purpose—to examine students’ life purpose’s influence on expected emotions to serve before engaging in service.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Expected positive and negative emotions. Students responded, on a scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely, to a prompt asking how much of each emotion they expected to experience during their service work related to this course. Items included the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) (Watson, Tellegen & Clark, 1988Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 1063-1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063) plus six additional items from the Positive Self Test (PST) (Fredrickson et al., 2003Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E. & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365-376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365) that are not represented in the PANAS but are expected to be useful in a service-learning context, four because of their self-transcendent focus (awe, grateful, optimistic, sympathetic) and two for their emphasis on disengagement (bored, disgusted). Positive and negative expected emotion scale scores were created by computing means across items for each scale. Eight PANAS plus four PST items measured positive emotions (a = .936). Twelve PANAS plus two PST items measured negative emotions (a = .866). Scales were not correlated (r = .04).

Predictors

Prior experiences with service-learning. A single item asked students: “Before this term, have you participated in any school-based service-learning?”

Sense of purpose and searching for purpose. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) (Steger, Frazier, Oishi & Kaler, 2006Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80-93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80) factors 10 items into two scales. Five items, such as “I understand my life’s meaning” and “My life has a clear sense of purpose,” measured sense of purpose on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = absolutely untrue to 7 = absolutely true, with one item reverse coded (a = .86). Five items, such as “I am looking to find my life’s purpose” and “I am searching for something that makes my life feel significant,” measured searching for purpose on the same Likert scale (a = .91). Scores were created for each scale by computing means. Scales were negatively correlated (r = -.29, p < .001).

Mediators

Intrinsic motivation. Five items responding to the question “Why are you motivated to do the service work in this course?” (“I want to help others,” “I enjoy it,” “The fieldwork is fun,” “I care about the particular people or issue I am helping,” “I want to try out my own ideas,”) measured intrinsic motivation on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = completely untrue to 7 = completely true. Scale score was created by averaging these items (a = .88). A confirmatory factor analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors showed good fit to the data. There was statistically significant group variance in intrinsic motivation ( = 0.15, Wald Z = 3.27, p < .001, with ICC = .12).

Helping identity. A single item was used: “Being involved in helping others defines who I am” with response options 1 = not at all, 2 = minimally, 3 = mildly, 4 = moderately, 5 = strongly, and 6 = more than anything else.

Control Measures

Extrinsic motivation. Using the same prompt as the intrinsic motivation items, two items measured extrinsic motivation: “I need to satisfy a requirement for graduation” and “I need to satisfy a requirement for my course/major.” Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation scales were slightly positively correlated (r = .13, p < .01).

Four dummy variables controlled for public versus private university since community service tends to be more supported in small private versus large public universities (Rockenbach et al., 2014Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D. & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and enduring commitments to community service in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2014.11777330), service-learning versus experiential courses because service oriented to community benefit tends to produce more prosocial orientation, whether the course was required or elective, and whether the student previously had volunteered in the community other than through service-learning (Eyler, Giles, Stenson & Gray, 2001Eyler, J., Giles, D., Stenson, C. & Gray, C. (2001). At a glance: What we know about the effects of service-learning on college students, faculty, institutions and communities, 1993-2000. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.).

Analytic Strategy

Multilevel SEM, with student at level 1 and course at level 2, was used to assess the effects of sense of purpose, searching for purpose, and past experiences with service-learning on expected positive and negative emotions during the service-learning class. Then we tested the extent to which helping identity, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation (as a control) were parallel mediators (Hayes, 2018Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.). All models were fit using MPlus, version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations among variables. Forty-one percent of students had prior service-learning experience, but prior experience was not related to purpose.

On average, students felt they “somewhat” had a sense of purpose but also that they “somewhat” were searching for a purpose. Students thought helping others “moderately” defined “who I am”. Students were “mostly” motivated to participate in service to help others or to enjoy it, were “a little” motivated to participate because they needed to satisfy a requirement, and expected “quite a bit” to feel positive emotions but to feel negative emotions only “a little” during their upcoming service work.

Someone with a high sense of purpose tended to not be searching for purpose and vice versa. Yet both searching and sense of purpose were positively associated with expected positive emotions, as were prior service experience, intrinsic motivation and helping identity. Sense of purpose and intrinsic motivation were negatively associated with expected negative emotions.

| Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Direct Effects

Table 3 shows direct effects of control and predictor variables on expected positive emotions and negative emotions.

Expected positive emotion. There was a statistically significant positive effect of prior volunteering experience on expected positive emotions (b = 0.16, SE = 0.06, p = .011, CI = [0.04, 0.27]) but no significant effects of any of the other control variables on positive emotion. As hypothesized, prior experience in service-learning courses had a significant positive effect on expected positive emotions (b = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p = .009, CI = [0.04, 0.26]). Both sense and searching for purpose had statistically significant effects on expected positive emotions, (respectively, b = 0.16, SE = 0.02, p < .001, CI = [0.11, 0.20], and b = 0.11, SE = 0.02, p < .001, CI = [0.08, 0.15]).

Expected negative emotion. Students at the public university expected significantly more negative emotions than students at the private university (b = -0.18, SE = 0.07, p = .008, CI = [-0.32, -0.05]) but no other control variables had significant effects. There was no significant effect of past service-learning (b = -0.03, SE = 0.04, p = .458, CI = [-0.12, 0.05]) nor of searching for purpose (b = -0.03, SE = 0.01, p = .389, CI = [-0.04, 0.02]). But there was a significant negative effect of sense of purpose on expectations for negative emotions (b = -0.08, SE = 0.02, p < .001, CI = [-0.12, -0.05]).

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation was included to control for how much students felt compelled to do the service work due to requirements for graduation or their major. Public university students reported significantly higher extrinsic motivation than private university students (b = 1.53, SE = 0.27, p < .001) and, as expected, extrinsic motivation was higher in required courses than in elective courses (p < .001).

| Table 3. Direct Effects Model Estimates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Students who reported past experiences with service-learning had significantly higher intrinsic motivation for engaging in the service-learning course (b = 0.40, SE = 0.08, p < .001, CI = [0.25, 0.56]). There were also positive effects on intrinsic motivation of both sense of purpose (b = 0.24, SE = 0.03, p < .001, CI = [0.18, 0.30]) and searching for purpose (b = 0.18, SE = 0.03, p < .001, CI = [0.13, 0.23]). Public university students reported lower intrinsic motivation than private university students (b = -0.32, SE = 0.14, p = .026, CI = [-0.59, -0.04]).

Helping identity. Public university students reported lower helping identity than private university students (b = -0.29, SE = 0.12, p = .025, CI = [-0.54, -0.04]). Past experience with service-learning was related to having a higher helping identity (b = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p < .001, CI = [0.04, 0.38]), as was sense of purpose (b = 0.28, SE = 0.04, p < .001, CI = [0.21, 0.35]) and searching for a purpose (b = 0.18, SE = 0.03, p < .001, CI = [0.13, 0.24]).

Indirect Effects

See figures 1a and 1b for diagrams of mediation model results. Mediation analyses were conducted to test the prediction that intrinsic motivation and helping identity mediate the relationship of past service-learning experiences, sense of purpose, and searching for purpose on expectations for positive emotions during service work but does not similarly mediate the relationship on expected negative emotions. University type, course type, course requirement, past volunteer experience, and extrinsic motivation were included in the models as controls. The Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation (MCMAM), a parametric bootstrap procedure, was used to test the indirect effects (Selig & Preacher, 2008Selig, J. P. & Preacher, K. J. (2008, June). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org/).

|

Figure 1A. This figure depicts the mediation model tested for expectations of positive emotions

|

|

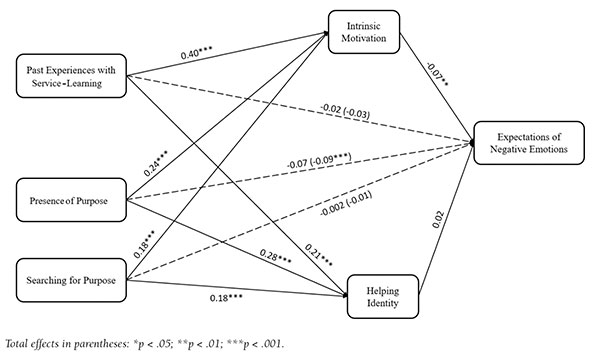

Figure 1B. This figure depicts the mediation model tested for expectations of negative emotions

|

Positive emotions. Intrinsic motivation fully mediates, and helping identity partially mediates, the effect of prior service-learning on positive emotions. Intrinsic motivation partially mediated both sense of purpose and searching for purpose on positive emotion, as did helping identity to a lesser degree. In sum, these tests provide evidence that the relationships between past service-learning experience, purpose, and expectations for positive emotions are explained by an increase in intrinsic motivation and a helping identity.

When controlling for intrinsic motivation and helping identity, there was no longer a statistically significant effect of past service-learning on expectation for positive emotions in upcoming service-learning (b = 0.006, SE = 0.05, p = .893, CI = [-0.10, 0.09]), providing evidence of complete mediation. Using MCMAM, the indirect effect of past service-learning on expected positive emotions through intrinsic motivation was found to be statistically significant (indirect = 0.17, CI = [0.10, 0.23], %mediated = 100), as well as the indirect effect through helping identity (indirect = 0.02, CI = [0.004, 0.04], %mediated = 14).

The effects of sense of purpose and searching for purpose on expected positive emotions were no longer statistically significant when controlling for intrinsic motivation and helping identity (respectively, b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p = .111, CI = [-0.01, 0.07], and b = 0.02, SE = 0.02, p = .270, CI = [-0.01, 0.05]). The indirect effect of sense of purpose on expected positive emotions through intrinsic motivation was statistically significant using the MCMAM (indirect = 0.10, CI = [0.07, 0.13], %mediated = 64) as was the indirect effect of searching for purpose through intrinsic motivation (indirect = 0.08, CI = [0.05, 0.10], %mediated = 67). The indirect effect of sense of purpose through helping identity was also significant (indirect = 0.03, CI = [0.02, 0.04], %mediated = 18) as was the indirect effect of searching through helping identity (indirect = 0.02, CI = [0.01, 0.03], %mediated = 16).

Negative emotions. Only sense of purpose had a statistically significant negative total effect on expectations for negative emotions, and intrinsic motivation was the only mediator with a significant effect. Thus, only a test of the indirect effects of sense of purpose on negative emotions through intrinsic motivation was performed. Intrinsic motivation partially mediated the relationship between sense of purpose and expectation of negative emotions such that sense of purpose was related to higher intrinsic motivation, which was related to lower chance of expecting negative emotions in one’s service work.

Specifically, in the model testing direct effects (see the last column of table 3) intrinsic motivation is related to significantly reduced negative emotions (b = -0.07, SE = 0.02, p = .001, CI = [-0.12, -0.03]), but helping identity had no significant effects (b = 0.02, SE = 0.02, p = .371, CI = [-0.02, 0.06]).

When controlling for intrinsic motivation and helping identity, sense of purpose retained a statistically significant direct effect on negative emotions. Thus, a sense of purpose was related to lower expectations of negative emotions above the effects of intrinsic motivation and helping identity. Although there was a direct effect of sense of purpose, there was a significant indirect, negative effect of sense of purpose through intrinsic motivation with lower negative emotions (indirect = -0.02, CI = [-0.03, -0.01], %mediated = 21).

This multilevel analysis of survey data from students at the start of service-learning courses in two US universities suggests that considering students’ life purpose before engaging in community service may help teachers better understand the emotional and motivational frames that students bring into their service work.

Our first and second hypotheses that sense of purpose and searching for purpose would be positively related to expected positive emotions toward service was mostly supported. Sense of purpose showed a moderate rather than a strong correlation. Searching for purpose showed an almost-as-high correlation with expected positive emotions as sense of purpose showed, which supports prior researchers’ assertions that service-learning may provide a structured environment for exploring possible ways for students to positively contribute (e.g., Malin et al., 2014Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B. & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186-199. doi: 10.1111/jora.1205).

In addition, sense of purpose buffered against expected negative emotions similarly to how past studies found sense of purpose buffers against other negative outcomes (e.g., Malin et al., 2017Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322; Miller, 1997Miller, J. (1997). The impact of service-learning experiences on students' sense of power. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 4, 16-21.). This buffering seemed to come from sense of purpose supporting intrinsic motivation, which then protected students from considering negative emotions (Burrow & Hill, 2011Burrow, A. L. & Hill, P. L. (2011). Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1196-1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818). Yet, despite the impact of these more proximal influences on expected emotions toward service work, sense of purpose, as a long-term meaningful aim, also directly related to lower expectations for negative emotions.

Our third hypothesis was also supported: life purpose’s effect on anticipated emotions toward service was partially mediated by the more proximal variables of having a helping identity and intrinsic motivation to serve. Intrinsic motivation was the stronger mediator, but helping identity also reduced the influence of purpose. Furthermore, the effect of prior service experience was fully mediated by intrinsic motivation, suggesting that experience contributes to enjoyment and recognition that the work is important, which then can influence anticipation of enjoying similar work in the future, corroborating past research (e.g., Soria & Thomas-Card, 2014Soria, K. M. & Thomas-Card, T. (2014). Relationships between motivations for community service participation and desire to continue service following college. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 53-64.; Stukas et al., 1999Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M. & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of "mandatory volunteerism" on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59-64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00107). Identifying as a helping person was much weaker as a mediator for both sense of purpose and searching for purpose on expected positive emotions.

There were also unhypothesized findings that nevertheless related to past research. University context mattered to extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and expected negative emotions, in alignment with past findings (Rockenbach et al., 2014Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D. & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and enduring commitments to community service in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2014.11777330). But this finding likely resulted from the experiential learning courses that were recruited at the public but not the private university. Prior service experience related to helping identity and intrinsic motivation to serve but did not correlate with purpose, which perhaps supports the idea that prior experience is carried forward through habit rather than purposeful intention (Wood et al., 2002Wood, W., Quinn, J. M. & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Habits in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1281-1297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1281 ). These unhypothesized findings require further investigation.

Limitations and further research. Despite this study linking purpose and service through emotional experience, we note some limitations. Other mediators should be considered, such as prosocial orientation (Hill et al., 2010Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001). A study with less variability in types of service work might test possible moderators of purpose’s effect on anticipated emotions during service, such as student’s level of commitment to their purpose, self-efficacy to serve, and alignment of the purpose’s specific aim with the specific tasks of the service work.

Although mediation analyses can suggest how one predictor’s influence might be absorbed by another more proximal variable to the outcome variable, this study’s correlational design cannot address actual causality. Longitudinal research that perhaps incorporates daily diaries of purpose salience, emotions, and motivations related to serving others may clarify the relationships introduced in this study.

This chapter was made possible in part through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, USA. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Cori Palermo managed all data collection surveys, plus cleaned and maintained data sets. Jenni Mariano collected some data.

| ○ | Barber, C. B., Mueller, C. T. & Ogata, S. (2013). Volunteerism as purpose. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.772775 |

| ○ | Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., DeWall, C. N. & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167-203. doi: 10.1177/1088868307301033 |

| ○ | Blattner, M. C. C., Liang, B., Lund, T. & Spencer, R. (2013). Searching for a sense of purpose. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 839-848. doi: 10.1016/adolescence.2013.06.008 |

| ○ | Bowman, N. A., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K., Hill, P. L. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Serving in college, flourishing in adulthood: Does community engagement during the college years predict adult well-being? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2, 14-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01020.x |

| ○ | Bronk, K. C. (2011). The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: A grounded model. New Directions for Youth Development, 132, 31-44. doi: 10.1002/yd.426 |

| ○ | Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27, 78-109. doi: 10.1177/0743558411412958 |

| ○ | Bronk, K. C., Hill, P., Lapsley , D., Talib, T. & Finch, W. H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 500-510. doi: 10.1080/17439760903271439 |

| ○ | Burrow, A. L. & Hill, P. L. (2011). Purpose as a form of identity capital for positive youth adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1196-1206. doi: 10.1037/a0023818 |

| ○ | Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J. & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516-1530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516 |

| ○ | Cruce, T. M. & Moore, J. V. (2012). Community service during the first year of college: What is the role of past behavior? Journal of College Student Development, 53(1), 399-417. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0038 |

| ○ | Damon, W. (2008). The path to purpose. New York, NY: Free Press. |

| ○ | Darby, A., Perry, S. & Dinnie, M. (2015). Students’ emotional experiences in direct versus indirect academic service-learning courses. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 3(1). |

| ○ | Dobrow Riza, S. & Heller, D. (2015). Follow your heart or your head? A longitudinal study of the facilitating role of calling and ability in the pursuit of a challenging career. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 695-712. doi: 10.1037/a0038011 |

| ○ | Eyler, J., Giles, D., Stenson, C. & Gray, C. (2001). At a glance: What we know about the effects of service-learning on college students, faculty, institutions and communities, 1993-2000. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. |

| ○ | Folgueiras, P. & Palou, B. (2018). An exploratory study of aspirations for change and their effect on purpose among Catalan university students. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 186-200. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1433643 |

| ○ | Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E. & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365-376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365 |

| ○ | Han, H. (2015). Purpose as a moral virtue for flourishing. Journal of Moral Education, 44(3), 291-309. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2015.1040383 |

| ○ | Harre, N. (2007). Community service or activism as an identity project for youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(6), 711-724. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20174 |

| ○ | Hart, D., Donnelly, T. M., Youniss, J. & Atkins, R. (2007). High school community service as a predictor of adult voting and volunteering. American Educational Research Journal, 44(1), 197-219. doi: 10.3102/0002831206298173 |

| ○ | Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. |

| ○ | Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., Brandenberger, J. W., Lapsley, D. K. & Quaranto, J. C. (2010). Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001 |

| ○ | Kasser, T. & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280-287. doi: 10.1177/0146167296223006 |

| ○ | Kiang, L. (2011). Deriving daily purpose through daily events and role fulfillment among Asian American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 185-198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00767.x |

| ○ | Kiang, L. & Fuligni, A. (2010). Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1253-1264. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z |

| ○ | King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L. & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179-196. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179 |

| ○ | Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B. & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186-199. doi: 10.1111/jora.1205 |

| ○ | Malin, H., Ballard, P. J. & Damon, W. (2015). Civic purpose. Human Development, 58, 103-130. doi: 10.1159/000381655 |

| ○ | Malin, H., Han, H. & Liauw, I. (2017). Civic purpose in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1384-1397. doi: 10.1037/dev0000322 |

| ○ | McKnight, P. E. & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 13, 242-251. doi: 10.1037/a0017152 |

| ○ | Miller, J. (1997). The impact of service-learning experiences on students' sense of power. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 4, 16-21. |

| ○ | Moran, S. (2010). Changing the world: Tolerance and creativity aspirations among American youth. High Ability Studies, 21(2), 117-132. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2010.525342 |

| ○ | Moran, S. (2016). What do teachers think about youth purpose? The Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(5), 582-601. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2016.1226556 |

| ○ | Moran, S. (2017). Youth purpose worldwide. Journal of Moral Education, 46(3), 231-244. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2017.1355297 |

| ○ | Moran, S. (2018). Purpose-in-action education. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 145-158. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1444001 |

| ○ | Moran, S. (2019). Youth life purpose: Evaluating service-learning via development of lifelong “radar” for community contribution. In P. Aramburuzabala, L. McIlrath & H. Opazo (eds.), Embedding service-learning in European higher education. Abington, UK: Taylor & Francis. |

| ○ | Moran, S., Bundick, M. J., Malin, H. & Reilly, T. S. (2013). How supportive of their specific purposes do youth believe their family and friends are? Journal of Adolescent Research, 28(3), 348-377. doi: 10.1177/0743558412457816 |

| ○ | Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. |

| ○ | Opazo, H., Aramburuzabala, P. & Ramírez, C. (2018). Emotions related to Spanish student-teachers’ changes in life purposes following service-learning participation. Journal of Moral Education, 47(2), 217-230. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1438992 |

| ○ | Quinn, B. (2013). Other-oriented purpose. Youth & Society, 46(6), 779-800. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12452435 |

| ○ | Reinders, H. & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 2-12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1 |

| ○ | Rockenbach, A. B., Hudson, T. D. & Tuchmayer, J. B. (2014). Fostering meaning, purpose, and enduring commitments to community service in college. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(3), 312-338. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2014.11777330 |

| ○ | Rockquemore, K. A. & Schaffer, R. H. (2000). Toward a theory of engagement. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 7, 1425. |

| ○ | Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13-39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0 |

| ○ | Seider, S. (2007). Frame-changing experiences and the freshman year: Catalyzing a commitment to service-work and social action. Journal of College & Character, 8, 1-15. doi: 10.2202/1940-1639.1168 |

| ○ | Seider, S. (2008). ‘Bad things could happen’: How fear impedes the development of social responsibility in privileged adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(6), 647-666. doi: 10.1177/0743558408322144 |

| ○ | Selig, J. P. & Preacher, K. J. (2008, June). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org/ |

| ○ | Soria, K. M. & Thomas-Card, T. (2014). Relationships between motivations for community service participation and desire to continue service following college. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 53-64. |

| ○ | Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80-93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 |

| ○ | Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B. & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 22-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004 |

| ○ | Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M. & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of "mandatory volunteerism" on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59-64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00107 |

| ○ | Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75, 360-384. doi: 10.1177/0190272512459662 |

| ○ | Vogelgesang, L. J. & Astin, A. W. (2005). Post-college civic engagement among graduates. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles. |

| ○ | Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 1063-1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 |

| ○ | Whitley, M. A. (2014). A draft conceptual framework of relevant theories to inform future rigorous research on student service-learning outcomes. Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 20(2), 19-40. |

| ○ | Wood, W., Quinn, J. M. & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Habits in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1281-1297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1281 |

¿Cómo se relaciona el sentido de los propósitos de la vida de los estudiantes universitarios de EE. UU. con sus expectativas emocionales de ser voluntario en la comunidad como parte de un curso de aprendizaje-servicio?

INTRODUCCIÓN. Pocos estudios consideran cómo el propósito de la vida predice las emociones relacionadas con el aprendizaje-servicio universitario, aunque el propósito, una “brújula” para encontrar oportunidades para realizar contribuciones prosociales significativas, debe motivar a los estudiantes a prestar servicio. MÉTODO. La ecuación estructural multinivel modela los efectos directos e indirectos de las respuestas de la encuesta con respecto a la experiencia pasada de servicio de los estudiantes, el sentido y la búsqueda del propósito en sus expectativas emocionales de aprendizaje-servicio antes de comenzar. RESULTADOS. Controlando la edad, el género, la motivación extrínseca y las características de las universidades y de los cursos, la experiencia pasada de servicio de los estudiantes y dos variables de propósito se relacionaron de manera positiva con las emociones positivas esperadas hacia el trabajo de servicio, mediadas a través de la identidad de ayuda de los estudiantes y la motivación intrínseca para servir. Solo el sentido de propósito se asoció con una mayor motivación intrínseca, que se asoció con una menor cantidad de emociones negativas esperadas. DISCUSIÓN. Tener en cuenta el propósito de la vida de los estudiantes puede estimular la motivación intrínseca y los esquemas de ser una persona que ayuda, lo que podría contribuir a crear emociones positivas hacia el servicio comunitario incluso antes de que comience el trabajo de servicio.

Palabras clave: Propósito de vida de los adolescentes, Aprendizaje-servicio, Educación postsecundaria, Comportamiento prosocial.

Quel rapport chez les étudiants américains entre leur sens de la vie et leurs attentes émotionnelles en tant que bénévoles pour la communauté dans le cadre d'un cours d'apprentissage par le service?

INTRODUCTION. Peu d'études examinent comment l'objectif de la vie prédit les émotions liées au service communautaire dans les cours des collèges, même si un objectif de la vie, une "boussole" permettant de trouver des occasions de faire des contributions prosociales significatives, devrait motiver les étudiants à s’engager dans des activités de service. MÉTHODE. La modélisation multiniveau par équation structurelle a permis d’estimer les effets directs et indirects des réponses à l’enquête sur l’expérience passée des étudiants en service, leur sens de la vie et leur quête d’un but dans la vie et leurs attentes émotionnelles d’apprentissage par le service avant d’en avoir eu l’expérience. RÉSULTATS. Tout en tenant compte de l'âge, du sexe, de la motivation extrinsèque et des caractéristiques des universités et des cours, le résultat est que l'expérience de service passée des étudiants et deux variables qui mesurent le but de la vie ont une relation positive avec les émotions positives que les étudiants s'attendent à ressentir pendant l’activité de service. Le sentiment de motivation apparaît comme associé à une motivation intrinsèque plus élevée, et une motivation intrinsèque plus élevée apparaît comme associée à des émotions négatives moins attendues. DISCUSSION. Considérer le but de la vie des étudiants pourrait stimuler la motivation intrinsèque et l'identification en tant que personne qui aide les autres, ce qui pourrait aider à créer des sentiments positifs sur le service communautaire avant même que le travail de service ne commence.

Mots-clés: But de la vie chez les adolescents, Apprentissage par le service, Etudes postsecondaires, Comportement prosocial.

Seana Moran (corresponding author)

Research Associate Professor in Developmental Psychology at Clark University. Ed.D., Harvard Graduate School of Education. Principal Investigator of $1.45 million grant and multinational collaboration to study how youth purpose development and service-learning experiences influence each other. Editor of two special issues of Journal of Moral Education on youth purpose around the world and on purpose-in-action education. Co-editor of special journal issue and book on teaching for purpose around the world.

E-mail: seanamoranclarku@gmail.com

Correspondence address: Clark University, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA, 01602 USA.

Randi Garcia

Assistant Professor of Psychology and of Statistical & Data Sciences, Smith College, Northampton, MA, USA. Ph.D, University of Connecticut. Statistician for Dr. Moran’s grant. Intergroup Relationships Lab studying gender-typed behavior, sexual objectification, racial attitudes and actor-partner interdependence models of group composition and member characteristics.

E-mail: rgarcia@smith.edu