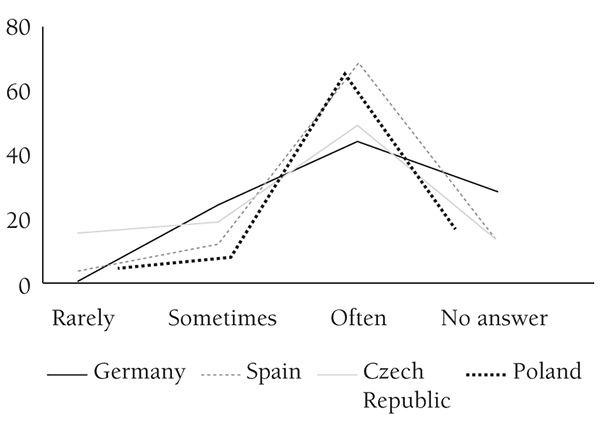

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of the frequency of the use of the interview

LUIS M. SOBRADO FERNÁNDEZ(1), ELENA FERNÁNDEZ REY(1) y REBECA GARCÍA MURIAS(2)

(1) Universidad de Santiago de Compostela

(2) Hochschule der Bundesagentur für Arbeit (HdBA)

DOI: 10.10.13042/Bordon.2019.52864

Fecha de recepción: 08/10/2017 • Fecha de aceptación: 01/10/2018

Autora de contacto / Corresponding author: Elena Fernández Rey. E-mail: elena.fernandez.rey@usc.es

INTRODUCTION. Within the European reality there are actions such as the Erasmus Plus initiative, the Ploteus Portal and the EURES network, which generate diverse academic and professional possibilities abroad. These initiatives increase the cultural and social exchange opportunities for young people, and boost their labour insertion opportunities in the European Union. Interviews, structured dialogues, websites, etc. have been highlighted amongst the instruments used by counsellors during guidance sessions regarding mobility opportunities. The European Project, “Guide My W@y” (Kreutzer & Iuga, 2016Kreutzer, F. & Iuga, E. (eds.) (2016). A European Career Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility. Bielefeld: Berterlsmann Verlag.) proposes action strategies and resources for vocational career counsellors which can be used in interviews. Likewise the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) competencies has been encouraged. The main objective of these counselling tools is to provide guidance professionals from different fields (EURES Network, Euroguidance, Public Employment Services (PES), Universities...) with the support that they require. METHOD. This study has been carried out in four European countries (Germany, Spain, Poland and Czech Republic), it firstly uses a descriptive methodology to analyse the role of the interview as a guidance strategy which can be used by counsellors in youth mobility processes, and subsequently a guidance proposal, based predominantly on the counsellors’ use of the virtual interview process as an intervention tool has been drawn up. RESULTS. Among the tools used in the guidance practices for international youth mobility processes in the four analysed countries, particular focus has been placed on the use of real and virtual interviews, conducting a specific frequency assessment. Likewise the relevance of using a questionnaire as an evaluation tool has been emphasised. DISCUSSION. The interviews implemented by the counsellors by means of virtual and face-to-face dialogues during the intervention process have been considered as an appropriate counselling strategy, and one that is of great value during guidance sessions regarding international mobility. The level of use and the degree of importance placed on the interview process by counsellors have served as the basis for drawing up a virtual dialogue proposal which will enable all young people who are involved in mobility processes in Europe to receive support.

Keywords: Counselling, Counsellor-client relationship, Counsellors, Educational mobility, Interviews, Occupational mobility.

european training and vocational mobility actions and programmes offer both academic and/or professional opportunities, as well as a wide range of possibilities for social and cultural exchange. These opportunities lead to a greater integration of young people in the European labour market in an overall context which is characterised by the free movement of workers in European countries (Kraatz & Ertelt, 2011Kraatz, S. & Ertelt, J. (eds.) (2011). Professionalization of career guidance in Europe. DGVT: Verlag.).

The main objective of this piece of research is to assess the role of the interview as a guidance resource in youth international mobility processes in four European countries: Germany, Spain, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Youth mobility is a highly significant component of the free people movement. It serves to promote employment opportunities and take steps towards reducing levels of poverty. Likewise it helps to foster active European citizenship and strengthen mutual and intercultural acceptance, and mobility actions such as these promote economic, social and regional cohesion (CEDEFOP, 2010CEDEFOP (2010). Guiding at-risk Young through learning to work. Lessons from across Europe. Thessaloniki: CEDEFOP.).

The research carried out by Freitag (2011Freitag, A. (2011). Mobility, Service Organisation and Guidance Needs: Recent trends in the International Placement Service (ZAV) in Germany. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.) Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 355-364). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag.) and Bélier (2011Bélier, A. (2011). Service Organisation and Career Guidance: EURES, France. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 365-370). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag.) is highly relevant for this particular study given that it deals with the guidance requirements, services and resources for European youth mobility.

When considering guidance within employment services, the research carried out by Sultana & Watts (2005Sultana, R. G. & Watts, A. (2005). Career Guidance in European Public Employment Services. Brussels: European Union.) is certainly worth mentioning, and likewise the work of Guichard (2008Guichard, J. (2008). Proposition d’un schema d’entretien constructivieste de conseil en orientation pour des adolescents ou de jeunes adultes. L’Orientations Scolaire et Professionnelle, 37, 25-51.) on the constructivist approaches for guidance interviews is very relevant.

In addition, Rübner (2011Rübner, M. (2011). Reorientation of Counselling and Training Placement for Young people in the German Public Employment Service. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 277-292). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag.) and Plant’s (2011Plant, P. (2011). Quality, Manual for youth Guidance Centres, Danmark. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 347-352). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag.) research is applicable to this study.

Last but not least, it is important to acknowledge that strategies which facilitate the communication between professionals and stakeholders are required in guidance processes for social, academic, professional and labour actions (Guichard, 2015Guichard, J. (2015). From vocational guidance and career counseling to life design dialogues. In L. Nota & J. Rossier (eds.), Handbook of life design. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishing.). In this respect, the interview process not only allows for direct action, but also for individualised interaction.

Research design: objectives

The following objectives have also been drawn up as guidelines for this piece of research:

Professional development and academic mobility in the European context: programmes and portals

The diverse levels of Higher Education and Vocational Training must be taken into account in European academic mobility programmes. Training and guidance must be provided with regards to the different modalities of educational institutions in these academic sectors (Nota & Rossier, 2015Nota, L. & Rossier, J. (eds.) (2015). Handbook of Life Design. Boston, MA: Hogrefe.).

Among the different actions offered to student academic mobility programmes in Europe the following ones can be mentioned (table 1).

| Table 1. Actions for the European youth mobility | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Greater coordination, communication and interaction are necessary between the Erasmus+ Programme and the EURES network in order to be able to establish a connection between the academic field and professional insertion in the labour market. This must form part of a wide and open concept which is designed to provide further training and continuous guidance throughout the individual’s lifetime (Hooley, 2015Hooley, T. (2015). The evidence base on lifelong guidance. Jyvaskyla: ELGPN.).

EURES Network seeks to provide individuals with lifelong guidance, as well as supporting them with labour and/or learning mobility actions throughout Europe. Through their Euro-counsellors, the network offers additional guidance intervention tools, helping with interview skills and providing access to the European Curriculum Vitae template (Europass), and the portfolio of competencies and skills, etc.

International youth mobility processes: social and labour insertion and stability

Historically in the field of Educational Sociology the oldest theories of Bourdieu & Passeron (1970) suggested that the insertion of young people from the popular classes is one of the important mechanisms of their social insecurity due to the weakness of their cultural power.

From 1980 to 1990 this concept was applied to the connections between training and work in the sense that it referred to the adaptation needs between the two variables.

In the European context (from 1990 to 2000), the “minimum integration income” was introduced in several countries. Its use was extended in order to indicate new aid policies which included work-seeking efforts, in particular for young people who had demonstrated interest. This term is used in many areas of the current system which include training, guidance, work and social policies, but it is not always confluent.

According to Guichard & Huteau (2007Guichard, J. & Huteau, M. (2007). Orientation et Insertion Professionnelle. Paris: Dunod.), in the socio-economic field, job search theories explain the complexity of professional insertion due to erroneous employment policies and the problems of labour transition.

Current theories concerning “post-school socialisation” indicate that confrontational experiences in the labour market are fundamental when building personal and professional identities (Athanasou & Van Esbroeck, 2010Athanasou, J. & Van Esbroeck, R. (eds.) (2010). International Handbook of Career Guidance. Dordrecht, ND: Springer.).

Social and professional youth insertion is currently proposed as an alternative to exclusion in order to complement transition, integration and social and labour inclusion (Senent, 2015Senent, J. (2015). Movilidad de estudiantes: Microanálisis del programa Erasmus (2009-2014). Estudio de Caso. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 67(1), 117-134. Recuperado de https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/Bordon.2015.67108).

Access to information regarding different mobility options should be linked to essential academic and professional guidance and counselling (Brown, 2012Brown, D. (ed.) (2012). Career choice and development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.).

It is important that the access requirements and mechanisms for entry visas for foreign citizens are fully understood (Arulmani et al., 2014Arulmani, G., Bakshi, A. J. & Leong, F. T. (2014). Handbook of Career Development: International perspectives. New York: Springer.). The counsellors in the applicant’s home country must provide sufficient, accurate legal, personal, social and labour information to any young people who wish to participate in a professional mobility programme in order to ensure that they do not face difficulties when trying to enter another country (European Commission, 2012European Commission (2012). Implementing Decision of the Commission of 26 November 2012 on the application of performance Regulation (EU) No 492/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council.).

According to Savickas (2012Savickas, M. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st Century, Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 13-19.), the role of the counsellor is to act as an information, training and professional advice agent, and this idea is based on the understanding that the counsellor’s task is to provide lifelong guidance, as in doing so, they will be able to ensure that the individuals are able to achieve their personal, academic and professional goals.

Guide My W@y European Research Project

The research project Erasmus+ “A European Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility, Guide My W@y” was developed in the period 2014-2016 and it was coordinated by the University of Applied Labour Studies in Germany.

Its main purpose was to establish a common and valid methodology for career counsellors in Europe when providing guidance to young people who show interest in participating in an international mobility programme. The European Career Guidance Concept (ECGC) was built from a reference model which is based on a German methodological concept called “BEKO” (e-Guidance Concept). This methodological concept, which had proved successful in Germany, is used by the Federal Employment Agency and it is based on offering counselling and advisory services which focus on professional practice. This methodology comprises of career guidance strategies in the field of transnational youth mobility and it includes a sequence of logical phases in order to provide support and guidance with regards to how proceed in practice, in addition to outlining the most appropriate resources that can be used.

This concept has a modular structure (which consists of eight topics) and it encompasses issues such as: career choice and career guidance, the international mobility profile, recognition of certificates and professional qualifications, legal issues, intercultural mobility aspects (social and cultural integration, language skills, leisure time organization…) and finally labour, educational and professional insertion.

This article aims to assess the use and importance of the interview process as a key guidance strategy in order to provide support for the international mobility of young people in the European context, and this will be done in two phases. The first phase explores the assessment of the use and importance of the interview process by counsellors as a guidance resource for youth mobility, taking into consideration the opinions of a group of counsellors from different European countries (Germany, Spain, Poland and Czech Republic) with regards to the use of this technique in their guidance practices. The aim of the second phase is to design a proposal which will enable the use of interview as a guidance resource in virtual sessions within the framework of the “Guide My W@y” research project.

The role of the interview in international mobility guidance processes

Communication based on respect is one of the most important elements of the interview process as this will allow a connection to be established between the counsellor and the young person. The language used, as well as the attitude and other contextual factors play a significant role in this. The interaction established between both actors “(…) helps the client to reflect on the situation and allows them to objectively analyse the situation by proposing activities that will help them to clarify issues, obtain information, experience a situation, or that will provide them with advice to aid them during the decision-making process (Sánchez, 2004Sánchez, M. F. (2004). Orientación laboral para la diversidad y el cambio. Madrid: Sanz y Torres.: 336).

Therefore, this technique facilitates individualised attention in order to provide the young people who are seeking guidance on mobility issues with a real understanding of the overall situation. Its primary function is to diagnose the needs and individual characteristics of the individual in order to help them to make the right decisions with regards to their future experiences abroad. In addition to this diagnostic function, and by means of the interview process, the individuals are also provided with information, advice and supervision, all of which enable them to make proper decisions.

Due to the versatility of the interview technique, it is commonly used for collecting information in most theoretical guidance approaches.

This technique will ensure that, by means of the relationship established between the counsellor and the young person who is intending to take part in a mobility process “(...), the young person is able to build their own life and career based on self-discovery and the identification of their own strengths and weaknesses and the consolidation of their own values (Marí, Bo & Marí, 2012Marí, R., Bo, R. M. & Marí, M. (2012). Transformar los retos en oportunidades. Entrevista de orientación para el momento actual. Revista Fuentes, 12, 207-232.: 210).

According to the aforementioned authors, by using dialogue in the interview process it is possible to discuss the young person’s life experiences with them, therefore helping them to improve their self-regulation and self-construction.

The use of the interview in guidance activities, especially within a virtual scenario is conditioned by whether or not the counsellor possesses the necessary skills. According to Patton & McMahon, (2014Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2014). Career Development and Systems Theory. Rotterdam: Sense Pub.) these include the ability to be able to communicate (through concepts, ideas, attitudes, etc.), to know how to listen (through reasoning, acceptance or comprehension) and to demonstrate ethical behaviour (guaranteeing respect, confidentiality of data, information, etc.)

The first phase of the Guide My W@y -GMW-project (Kreutzer & Iuga, 2016Kreutzer, F. & Iuga, E. (eds.) (2016). A European Career Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility. Bielefeld: Berterlsmann Verlag.) explored the counsellors’ professional practice and their personal experiences. It used a questionnaire which covered different issues connected to the provision of guidance for youth international mobility programmes.

Questionnaire regarding the guidance interview

The questionnaire was developed within the framework of the GMW project and its aim was to explore the attitudes and competencies of EURES advisors, Euroguidance counsellors, and other guidance practitioners (at a local, regional and national level) from the different European countries that have been analysed.

The questionnaire was designed by the project partners and it was disseminated to the aforementioned groups as an online tool. Once the questionnaires had been completed, they were sent by e-mail to the researchers who were responsible for this project in each of the participating countries for subsequent analysis.

The aim of this survey was to collect research data and it included 33 questions which were divided into two sections, with 21 open-ended questions and 12 closed-ended questions.

The first section was based on the counsellors’ professional profile and it analysed the real interview processes used during the guidance sessions. The section two dealt with the use of virtual interviews (HdBA, 2015HdBA (2015). Evaluation Report of the Delphi Questionnaire. Mannheim: Guide My W@y. University of Applied Labour Studies (HdBA).).

Analysis of the opinions of counsellors on the use of interviews in guidance processes for the mobility of young people in Europe

The questionnaire was sent by e-mail by the different partners involved in the research to a total sample of 177 professionals (labour and educational guidance counsellors from Universities, Employment Services, the EURES network, Chambers of Commerce, Trade Unions, etc.)

The questions referred to the frequency in which the interviews were carried out, with three possible answers (often, sometimes, rarely), and to the level of importance given to the interview during the counselling practice, with five possible answers (on a numerical scale from five-very important- to one- not important-). In addition, there were also open-ended questions which dealt with the different aspects of the interview as a guidance resource (7 issues).

Analysis of the counsellors’ data: description

The data listed below was analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics programme, version 25 in order to carry out a descriptive analysis.

a) Total number of counsellors

A total of 177 counsellors responded to this questionnaire (34 EURES counsellors and 143 who belonged to “other counsellors”). The distribution with respect to the participating countries is indicated in table 2.

| Table 2. Distribution of participants. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The participants were from: Poland (42%), Czech Republic (31.50%), Germany (13.50%) and Spain (13%). 48% of them were professionals in the University field; 22% of the participants worked for the EURES network; 26% in the Public Employment Services and 4% of the counsellors worked in the private sector.

It was also interesting to discover how many EURES counsellors had contributed to this study from each country. In the case of Poland however, the participants did not indicate their home institution, so we were unable to obtain this information.

Since its creation in 1993, this EURES network has helped jobseekers to find jobs in other EU countries as well as providing training opportunities. One of its other main objectives is to offer information and counselling services with regards to the labour market in each of the European Union Member Countries. Following the reformations which were adopted by the European Commission in 2012, the network now places more emphasis on the greater mobility of young people rather than that of other groups. EURES also provides information regarding work and training opportunities abroad, and offers advice on different employment paths which combine employment with workplace training experiences, for example apprenticeships (in the framework of the VET programmes).

Therefore, one of the purposes of this study was to explore the opinion of EURES counsellors on the use of the interview when providing guidance to young people looking for employment opportunities through mobility processes.

a) Descriptive analysis by Spanish counsellors

The main personal, academic and professional data obtained from the Spanish counsellors from the questionnaire responses.

Ten additional items were included in order to obtain data which was not requested in the original questionnaire.

With regards to their personal information, 60.87% of counsellors were aged between 40 and 49 years old, and 30.43% were aged between 50 and 59. In terms of their gender, 56.52% were male, compared to 43.48% who were female.

With regards to their academic information, information was collected about the participants’ educational background. 39.13% had a Master’s degree; 26.09% a Bachelor’s degree and 35% had another academic qualification. 34.78% of the counsellors had a degree in Educational Sciences and 30.43% had studied Psychology and 35% of the counsellors had studied a different degree (Teaching, Sociology, etc.)

With regards to their professional career, 73.91 % of counsellors had worked for over 15 years, 43.48% had exercised as labour practitioners and 43.50% were EURES counsellors.

With regards to the guidance services where they worked, 27.83% worked at a university; 43.50% worked for the EURES network; 26.08% worked in Public Employment Services and 2.59% worked in the private sector.

In summary, the most common personal and professional profile of the counsellors who participated in this questionnaire was: middle-aged individuals, generally males, with a Master’s Degree and qualifications in Educational Sciences and Psychology. Moreover, the analysed group possessed considerable professional experience and the most common professional role was a labour counsellor working for the EURES network, a university or the Public Employment Services (PES).

b) Frequency and importance of the interview by counsellors

1) Use of the interview

The analysed results obtained from the answers submitted by the counsellors have been presented in table 3. This table shows their responses to the question with regards to the frequency of the use of the interview in their daily professional practice when dealing with international mobility issues for young people, and the data is classified by country.

Moreover, table 3 shows the opinions of both EURES counsellors and other counsellors. In the case of Poland however the participants did not indicate their home institution, so we were unable to obtain this information.

| Table 3. Frequency in the use of the interview by counsellors. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As demonstrated in table 3, the constant use of the interview has been highlighted (reaching values ranging between 65-100%), and its use is particularly frequent by the EURES counsellors from Germany (77.78%); Czech Republic (73.33%) and Spain (70%).

According to the results, a high percentage of Spanish counsellors (69.23%) used the interview as a guidance resource, however a significant number of the German counsellors (46.67%) did not answer this question. The reason for this is that they use other guidance resources such as the European Curriculum Vitae, the questionnaire and the portfolio of competencies, etc.

It is interesting to point out that in all cases, the EURES counsellors demonstrated the same levels as the counsellors from other institutions.

Out of the four analysed countries, the interview was most commonly used by Spanish counsellors (69.57%), followed closely by Polish counsellors (66.22%).

The frequency of the use of the interview has been analysed and the results from the four countries have been compared (table 3, figure 1). According to these results, the Spanish counsellors chose the highest level (“often”) in the greatest number of occasions, and this was also the most common choice amongst the Polish counsellors, however only 50% of the Czech Republic counsellors, and 45.83% of the German counsellors chose this option.

|

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of the frequency of the use of the interview

|

2. Importance of the interview

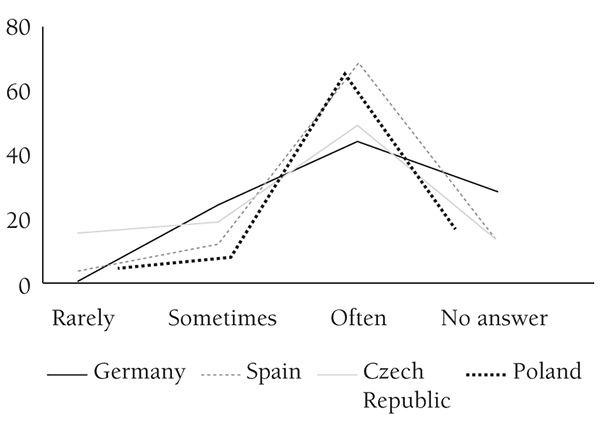

With regards to the level of importance that counsellors place on the interview, in figure 2 the average and global values (4.55/5) can be observed for each European country.

|

Figure 2. Average level of importance placed on the interview

|

All of the counsellors, with slight differences depending on the country, considered the interview to be a positive guidance resource for their professional activity regarding mobility. The highest score was obtained by Polish counsellors (4.94/5) whereas German counsellors showed the lowest value (4.23/5).

Designing a proposal for using the interview as a guidance resource by counsellors in virtual sessions

This kind of interview may combine acoustic communication (telephone support), with video communication, meaning that it is possible to both hear and see the interviewee using verbal and non-verbal language. This allows for off-site, virtual communication rather than just conventional face-to-face interviews.

A virtual interview may require more than just a simple internet connection. For example, the counsellor and their client might choose to write on a digital board, or share files and documents.

One of the great advantages of the virtual interview when compared to a face-to-face interview, is that the guidance process can take place from anywhere, meaning that in cases of international mobility the counsellor and their client may be in direct contact, despite being in different geographical or time zones. It is possible to provide young people with support and advice regarding any mobility issues that might arise when they move and live abroad.

With regards to the limitations of the virtual interview, the speed and quality of the connection are not always suitable, and the different time zones can make planning the appointments and conducting the interviews, etc. quite difficult.

The main issues mentioned by the guidance practitioners from the four countries when asked about the use of the virtual interview as the main ICT resources for international youth mobility, were as follows:

Firstly, in terms of the frequency with which this tool is used, the results show that 51.5% of the practitioners had never conducted a virtual interview during their counselling intervention, 25.8% had done it very rarely, and 12.1% stated that they sometimes use this tool (one or two times per month).

In contrast, only 1.5 % of the counsellors stated that they always conduct virtual interviews during the counselling process and 9.1% replied that they use this tool often (once or twice a week).

It should be noted that only 22.70% of counsellors conduct virtual interviews periodically.

When considering the kind of experiences that guidance practitioners have had with virtual interviews, the results indicate that: 46% of them have used the telephone for remote interviews; 27% have conducted interviews via Skype; 18% have used e-mail as a personal communication resource and the remaining practitioners (9%) have used video, chat, forums, etc.

When asked about their opinion regarding the importance of using virtual interviews, it is worth mentioning that only 15.2% of them considered virtual interviews relevant for their professional activity in the near future. In fact, 1.5% does not place any importance on this tool and 13.7% claim that they will rarely use it.

Moreover, 48.5% of counsellors consider virtual interviews to be irrelevant as guidance intervention tools. On the other hand, 36.3% of counsellors show more positive values, stating that virtual interviews are quite important (31.8%) or very important (4.5%) in the short term for their professional activity as guidance counsellors.

In terms of the usefulness of the virtual interview with regards to its contextualisation, the results obtained showed that: 28% of practitioners considered it to be useful for guidance intervention processes between the counsellor and their client; 18% of them considered it to be beneficial in emergency situations; 13% considered it to be beneficial for using with social networks; 24% claimed that it was useful when counselling disabled people; 7% pointed out that it would be useful for preparing their client for job interviews, creating their CV, etc.; 4% felt that it is important for young people who have moved abroad and who would like to maintain contact with the counsellor from their home country during their stay abroad; 4% claimed that it was useful for group counselling and, 2% stated that it is profitable and can reduce expenses.

These results highlighted the usefulness of conducting virtual interviews in the case in which the client is located in a different geographical zone, as well as highlighting its usage with disabled individuals as a target group for guidance intervention.

Suggestions for the virtual interview in the future

Technical security, the necessary software and a proper internet connection, which is fast enough to be able to properly use e-mail, Skype, social networks, etc. must be guaranteed.

Virtual interviews must be complemented with face-to-face interviews. Guidance professionals must undergo permanent training to help them acquire ICT competencies, and this training should also focus on ethical issues within their professional performance and should cover the theoretical and practical domain of the guidance interview.

Innovative methodologies and technologies are required for guidance, underlining the central role of the beneficiaries, in particular in the case of young people providing them with self-guidance.

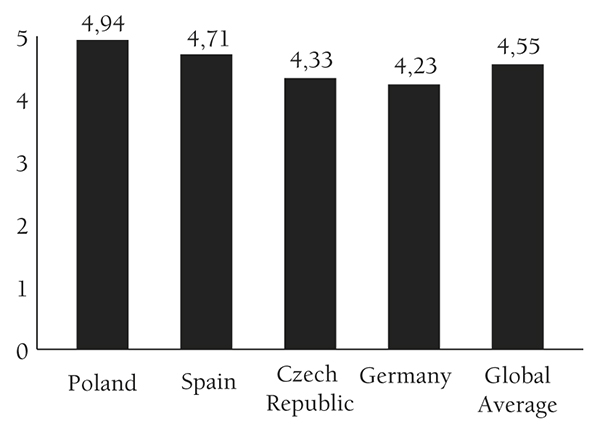

Phases of the counselling interview

The counselling interview process is developed in five phases (figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Phases of the counselling interview.

|

The main aspects of the first phase which is the opening dialogue, are as follows:

The dialogue techniques which should be used during the interview include liveliness, active listening, paraphrasing, empathic, sympathy, formulation of open-ended questions, etc. (Reid, 2016Reid, H. (2016). Introduction to Career Counselling & Coaching. London: Sage Pub.).

In the situation analysis phase, the previous reality of the party being interviewed must be identified as well as their individual motivation, interest, training, etc. The tools which are to be developed in this phase include: open-ended, introductory and advanced questions, active listening, alternative options and paraphrasing.

Defining the main objective is the fundamental element of the third phase and the goals must be clearly defined with the party who is being interviewed. The criteria to be considered when formulating shared goals include: their specific nature (particular fields to be improved) and the timeframe for the established targets.

A diverse range of tools may be used including, advanced open-ended questions, synthesis and alternative options.

The fourth stage is characterised by the development of response strategies to certain situations raised in the interview, this includes information on search and management tasks, how to successfully develop specific action procedures, and how to establish contacts that can help the party being interviewed to make the right decision.

The final phase is the conclusion. The content of the discussion is summarised at the end of the session, focusing on the main issues which were raised and subsequently solved as well as the respective feedback.

Likewise, it is necessary to define the situations and problems and present perspectives regarding further steps in the future, for instance by carrying out further interview sessions. In most of the cases, this phase ends with a friendly farewell by the party being interviewed, having first given them encouragement for their decision making process and discussed the possibility for further communication.

In order to assess the counsellors’ opinions on the use of the interview when providing guidance to young people who are preparing a mobility action in the European context, we focused on two dimensions: frequency of use and the level of importance placed on this guidance intervention tool.

The interview was very commonly used among the sample of counsellors from the analysed European countries.

Moreover, guidance processes for mobility issues require a personal interaction between the counsellor and the young person that can only be achieved by carrying out an interview. This guidance resource might make it easier to address personal and contextual situations in addition to diverse and complex issues, and it may also promote global understanding. According to Sánchez (2011Sánchez, M. L. (coord.) (2011). Guía práctica del asesor y orientador profesional. Madrid: Síntesis.), this counselling procedure will have a positive effect on the decision to participate in a mobility programme.

The use of the interview is probably the most relevant of all of the tools due to the versatility of this technique in terms of its guidance functions such as: diagnosis, information, advice or supervision.

The intrinsic nature of guidance, which is help, is essential for youth mobility initiatives, taking into consideration the endless number of issues and enquires that can arise regarding legal, intercultural, educational, labour aspects, etc. In these situations, the counsellors should focus on encouraging their client to reflect on the situation, clarifying the main objective and analysing the situation. Likewise the counsellor should provide different tips and strategies for searching for and obtaining information. According to Sánchez (2004Sánchez, M. F. (2004). Orientación laboral para la diversidad y el cambio. Madrid: Sanz y Torres.), if proper advice is given, the person should be able to make their own decisions. As a consequence, counsellors usually favour interview processes given that this resource facilitates reflection, analysis and advice.

The high frequency of the use of this tool is commensurate with the high level of importance that counsellors place on it, which has been justified by the reasons stated above. The counsellors from the four European countries that were analysed for this research paper, all considered the interview as a very important guidance resource for counselling sessions regarding European youth mobility processes and deemed it more relevant than other resources (diagnostic tests, application letters, CVs).

The real advantage of virtual interviews as opposed to face-to-face meetings is that the guidance process can be performed from a distance which is especially helpful when providing counselling to young people with regards to living, training and/ or working conditions in an international scenario.

However, this guidance resource is still very rarely used instead of face-to-face interviews (only 22.70% of the counsellors stated that they use it occasionally). The technological resources which are most commonly used in virtual interview situations are telephone, Skype and e-mail.

It should be noted that 85% of the counsellors pointed out that this may be of great importance for their professional practice in the future. Currently, face-to-face and virtual interviews should be complemented with other resources and this tool must be used in the most appropriate guidance situations for international youth mobility (Cohen-Scali, Rossier & Nota, 2018Cohen-Scali, V., Rossier, J. & Nota, L. (eds.) (2018). New perspectives on Career Counseling and Guidance in Europe. Berlin: Springer.).

Mobility promotes quality in education, training or work, it improves the participants’ academic and professional profile, offering them greater levels of freedom and flexibility, therefore meaning that they are able to benefit from training or work opportunities abroad. In addition, these European initiatives offer the possibility for individuals to live and work in another country as part of a multicultural and intercultural team, leading to the improvement and enrichment of their linguistic, social, professional and cultural competencies and skills (Borbély-Pecz & Hutchinson, 2013Borbély-Pecze, T. & Hutchinson, J. (2013). The youth guarantee and Lifelong Guidance. Jyvaskyla: ELGPN.).

Due to the economic crisis in many European countries, young people are currently fighting unemployment and their prospects for finding a proper job, which matches their professional competencies and qualifications, in their home country are often limited. International mobility programmes enable them to search for a wider range of employment opportunities in another country, but adequate counselling, provided by a skilled professional, is required in order to provide these young people with the support and advice that they need to successfully deal with this issues (Patton & McMahon, 2014Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2014). Career Development and Systems Theory. Rotterdam: Sense Pub.).

The complexity of the situations that may arise for young people who wish to carry out a mobility action, combined with the multiplicity of factors that might come into play, are often perceived as barriers to this mobility (linguistic-cultural reasons, logistical support, recognition of qualifications and professional competences, etc.), and innovative guidance strategies, adapted to the real needs of these individuals must be implemented by counselling professionals.

The interview is used as a guidance tool by practitioners from different institutions (the EURES network, University or Public Employment Services) and from a range of European countries (Germany, Spain, Czech Republic and Poland). Therefore, the interview has a qualitative character of interpersonal or virtual communication that is open to diverse and complex situations, as well as to personal, social, academic and professional realities. The overall average result obtained from the counsellors surveyed in this study (4.55/5) indicates that the interview resource is frequently used. In addition, they value it very positively when providing guidance for international youth mobility processes.

The opportunity to establish a dialogue focused on three main factors in order to initiate a proper guidance intervention with the young persons (needs, characteristics, competences and situation) as well as the possibility of obtaining an appropriate level of understanding, may be two of the main reasons why most of the counsellors consider the interview to be the most important resource that can be used in their professional practice.

The interview carried out in a virtual context between a counsellor and their client is an essential guidance tool, especially in the field of international youth mobility (Hawley, Hall & Weber, 2012Hawley, J., Hall, A. & Weber, T. (2012). Effectiveness of Policy Measures to increase the Employment Participation of Young People. Dublin: EFILWC.). This technique provides a general approach to counselling intervention, using a holistic perspective (Suárez, Padilla & Sánchez, 2013Suárez, M., Padilla, M. T. & Sánchez, M. F. (2013). Factores condicionantes del desarrollo de buenas prácticas en servicios de orientación de personas adultas. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo. RIDE, 11.), and it promotes a deeper communication between the counsellor and the young person.

Within the framework of the Guide My W@y Erasmus+ Project, in addition to analysing the role of the interview as a guidance resource, a proposal was also drawn up for virtual interview sessions and this is currently in the implementation and evaluation phase.

The interview plan is developed in five stages: opening, situation analysis, formulation of objective/s, implementation and conclusion.

The project partners have also constructed an interview grid for each of the eight modules that make up the European Career Guidance Concept (ECGC) and they have developed several examples of virtual dialogues in order to help European Career Counsellors perform their guidance tasks, which include providing support to young people for international mobility experiences.

| ○ | Arulmani, G., Bakshi, A. J. & Leong, F. T. (2014). Handbook of Career Development: International perspectives. New York: Springer. |

| ○ | Athanasou, J. & Van Esbroeck, R. (eds.) (2010). International Handbook of Career Guidance. Dordrecht, ND: Springer. |

| ○ | Bélier, A. (2011). Service Organisation and Career Guidance: EURES, France. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 365-370). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag. |

| ○ | Borbély-Pecze, T. & Hutchinson, J. (2013). The youth guarantee and Lifelong Guidance. Jyvaskyla: ELGPN. |

| ○ | Brown, D. (ed.) (2012). Career choice and development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. |

| ○ | CEDEFOP (2010). Guiding at-risk Young through learning to work. Lessons from across Europe. Thessaloniki: CEDEFOP. |

| ○ | Cohen-Scali, V., Rossier, J. & Nota, L. (eds.) (2018). New perspectives on Career Counseling and Guidance in Europe. Berlin: Springer. |

| ○ | European Commission (2012). Implementing Decision of the Commission of 26 November 2012 on the application of performance Regulation (EU) No 492/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council. |

| ○ | Freitag, A. (2011). Mobility, Service Organisation and Guidance Needs: Recent trends in the International Placement Service (ZAV) in Germany. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.) Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 355-364). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag. |

| ○ | Guichard, J. (2008). Proposition d’un schema d’entretien constructivieste de conseil en orientation pour des adolescents ou de jeunes adultes. L’Orientations Scolaire et Professionnelle, 37, 25-51. |

| ○ | Guichard, J. (2015). From vocational guidance and career counseling to life design dialogues. In L. Nota & J. Rossier (eds.), Handbook of life design. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishing. |

| ○ | Guichard, J. & Huteau, M. (2007). Orientation et Insertion Professionnelle. Paris: Dunod. |

| ○ | Hawley, J., Hall, A. & Weber, T. (2012). Effectiveness of Policy Measures to increase the Employment Participation of Young People. Dublin: EFILWC. |

| ○ | HdBA (2015). Evaluation Report of the Delphi Questionnaire. Mannheim: Guide My W@y. University of Applied Labour Studies (HdBA). |

| ○ | Hooley, T. (2015). The evidence base on lifelong guidance. Jyvaskyla: ELGPN. |

| ○ | Kraatz, S. & Ertelt, J. (eds.) (2011). Professionalization of career guidance in Europe. DGVT: Verlag. |

| ○ | Kreutzer, F. & Iuga, E. (eds.) (2016). A European Career Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility. Bielefeld: Berterlsmann Verlag. |

| ○ | Marí, R., Bo, R. M. & Marí, M. (2012). Transformar los retos en oportunidades. Entrevista de orientación para el momento actual. Revista Fuentes, 12, 207-232. |

| ○ | Nota, L. & Rossier, J. (eds.) (2015). Handbook of Life Design. Boston, MA: Hogrefe. |

| ○ | Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2014). Career Development and Systems Theory. Rotterdam: Sense Pub. |

| ○ | Plant, P. (2011). Quality, Manual for youth Guidance Centres, Danmark. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 347-352). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag. |

| ○ | Reid, H. (2016). Introduction to Career Counselling & Coaching. London: Sage Pub. |

| ○ | Rübner, M. (2011). Reorientation of Counselling and Training Placement for Young people in the German Public Employment Service. In S. Kraatz & B. Ertelt (eds.), Professionalisation of Career Guidance in Europe (pp. 277-292). Tubingen: Dgvt, Verlag. |

| ○ | Sánchez, M. F. (2004). Orientación laboral para la diversidad y el cambio. Madrid: Sanz y Torres. |

| ○ | Sánchez, M. L. (coord.) (2011). Guía práctica del asesor y orientador profesional. Madrid: Síntesis. |

| ○ | Savickas, M. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st Century, Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 13-19. |

| ○ | Senent, J. (2015). Movilidad de estudiantes: Microanálisis del programa Erasmus (2009-2014). Estudio de Caso. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 67(1), 117-134. Recuperado de https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/Bordon.2015.67108 |

| ○ | Suárez, M., Padilla, M. T. & Sánchez, M. F. (2013). Factores condicionantes del desarrollo de buenas prácticas en servicios de orientación de personas adultas. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo. RIDE, 11. |

| ○ | Sultana, R. G. & Watts, A. (2005). Career Guidance in European Public Employment Services. Brussels: European Union. |

| Websites | |

| ○ | Erasmus Mundus: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/erasmus_mundus/ |

| ○ | Erasmus Plus: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/node_en |

| ○ | EURES The European Job Mobility Portal: https://ec.europa.eu/eures/eures-searchengine/page/main?lang=en#/simpleSearch |

| ○ | European Commission: http://ec.europa.eu/index_en.htm |

| ○ | Guide My W@y: www.guidemyway.eu |

| ○ | Ploteus Portal: http://ec.europa.eu/ploteus/ |

La entrevista como recurso de orientación en los procesos de movilidad europea de la juventud

INTRODUCCIÓN. En la realidad europea existen acciones como Erasmus+, Ploteus o Red EURES que generan posibilidades académicas y profesionales y, consecuentemente, de intercambio cultural, social y de inserción laboral de los jóvenes en la Unión Europea. Entre los instrumentos orientadores usados por los Consejeros destacan la entrevista, los diálogos estructurados, web, etc.El Proyecto Europeo “Guide My W@y” (Kreutzer & Iuga, 2016Kreutzer, F. & Iuga, E. (eds.) (2016). A European Career Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility. Bielefeld: Berterlsmann Verlag.) propone estrategias y recursos de actuación a través del uso de la entrevista y de las Tecnologías de la Información y de la Comunicación (TIC) como soporte de la acción orientadora destinada a las iniciativas de movilidad de los jóvenes y pretende apoyar a los profesionales de la orientación de diferentes ámbitos (Red EURES, Euroguidance, agencias de empleo, universidades ). MÉTODO. El estudio, realizado en cuatro países de la Unión Europea (Alemania, España, Polonia y República Checa), analiza a través de una metodología descriptiva el papel de la entrevista como estrategia orientadora en los procesos de movilidad de la juventud utilizada por los profesionales de la orientación y diseña una propuesta orientadora basada, fundamentalmente, en la entrevista a usar por los Consejeros en las sesiones virtuales. RESULTADOS. Entre los instrumentos utilizados en la práctica orientadora de los cuatro países en cuestiones relativas a la movilidad de los jóvenes destaca el empleo de la entrevista, real y virtual con valoración específica de su frecuencia e importancia a través del cuestionario aplicado. DISCUSIÓN. La entrevista, expresada a través del diálogo virtual en situaciones de no presencialidad del orientador en la intervención, resulta una estrategia asesora adecuada y de gran valor en los procesos de movilidad e intercambio de los jóvenes. Lo ratifica el nivel de uso y el grado de importancia que le otorgan los orientadores y que sirve de base para el diseño de una propuesta de diálogo virtual para el asesoramiento de jóvenes europeos en procesos de movilidad.

Palabras clave: Asesoramiento, Entrevista, Movilidad educativa, Movilidad ocupacional, Orientadores, Relación orientador-cliente.

L’interview comme ressource d’orientation dans les processus de mobilité européenne des jeunes

INTRODUCTION. Dans la réalité européenne, de nombreuses initiatives sont menées, Erasmus+, Ploteus ou Réseau EURES, créant des possibilités universitaires et professionnelles et, par conséquent, d’échange culturel, social et d’insertion professionnelle pour les jeunes de l’Union européenne. Parmi les outils d’orientation utilisés par les Conseillers se distinguent les interviews, des débats structurés, site Internet, etc. Le projet européen « Guide My W@y » (Kreutzer & Iuga, 2016Kreutzer, F. & Iuga, E. (eds.) (2016). A European Career Guidance Concept for International Youth Mobility. Bielefeld: Berterlsmann Verlag.) propose des stratégies et des ressources d’action au moyen d’interviews et de technologies de l’information et de la communication (TIC) comme support de l’action d’orientation affectés aux activités de mobilité des jeunes et vise à soutenir les conseillers d’orientation de différents domaines (Réseau EURES, Euroguidance, agences pour emploi, universités ). MÉTHODE. L’étude, réalisée dans quatre pays de l’Union européenne (Allemagne, Espagne, Pologne et République tchèque), analyse au moyen d’une méthode descriptive le rôle de l’interview comme stratégie d’orientation dans les processus de mobilité des jeunes utilisée par les conseillers d’orientation et, d’autre part, il élabore une proposition d’orientation reposant essentiellement sur l’interview utilisée par les Conseillers lors des sessions virtuelles. RÉSULTATS. Parmi les outils utilisés dans la pratique d’orientation des quatre pays sur les questions relatives à la mobilité des jeunes se distingue l’interview réelle et virtuelle, notamment avec évaluation de la fréquence et de son importance dans le cadre d’un questionnaire. DÉBAT. L’interview, exprimée par voie d’un dialogue virtuel hors de la présence du conseiller au débat, devient une stratégie consultative appropriée et à forte valeur dans les processus de mobilité et échange des jeunes. Cela est ratifié par le niveau d’utilisation et le degré d’importance conféré par les conseillers, et qui constitue la base pour l’élaboration de la proposition du dialogue virtuel pour le conseil des jeunes européens dans les processus de mobilité.

Mots-clés: Conseil, Interview, Mobilité universitaire, Mobilité professionnelle, Conseillers, Rapport conseiller d’orientation-client.

Elena Fernández Rey (autora de contacto)

Full Professor at University of Santiago de Compostela. Director of Research Group “Diagnóstico y Orientación Educativa y Profesional” (DIOEP). Her research focuses on career guidance, training of career guidance and counselling professionals and ICT in guidance.

Correo electrónico de contacto: elena.fernandez.rey@usc.es

Dirección para la correspondencia: Facultade de Ciencias de la Educación. Campus Vida. 15782. Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña). Teléfono: (+34)881813696

Luis M. Sobrado Fernández

Ph.D. in Educational Sciences (Pedagogy). Degree in Pedagogical Psychology and senior Professor at University of Santiago de Compostela. He was an ICE director and of the Research and Diagnosis Methods Department in Education.

Correo electrónico de contacto: luismartin.sobrado@usc.es

Rebeca García Murias

Ph.D. in Educational Sciences. Postdoctoral Scholar at the University of Applied Labour Studies (Mannheim, Germany). Her research focuses on career guidance, training of career guidance and counselling professionals and mobility.

Correo electrónico de contacto: Rebeca.Garcia-Murias@arbeitsagentur.de